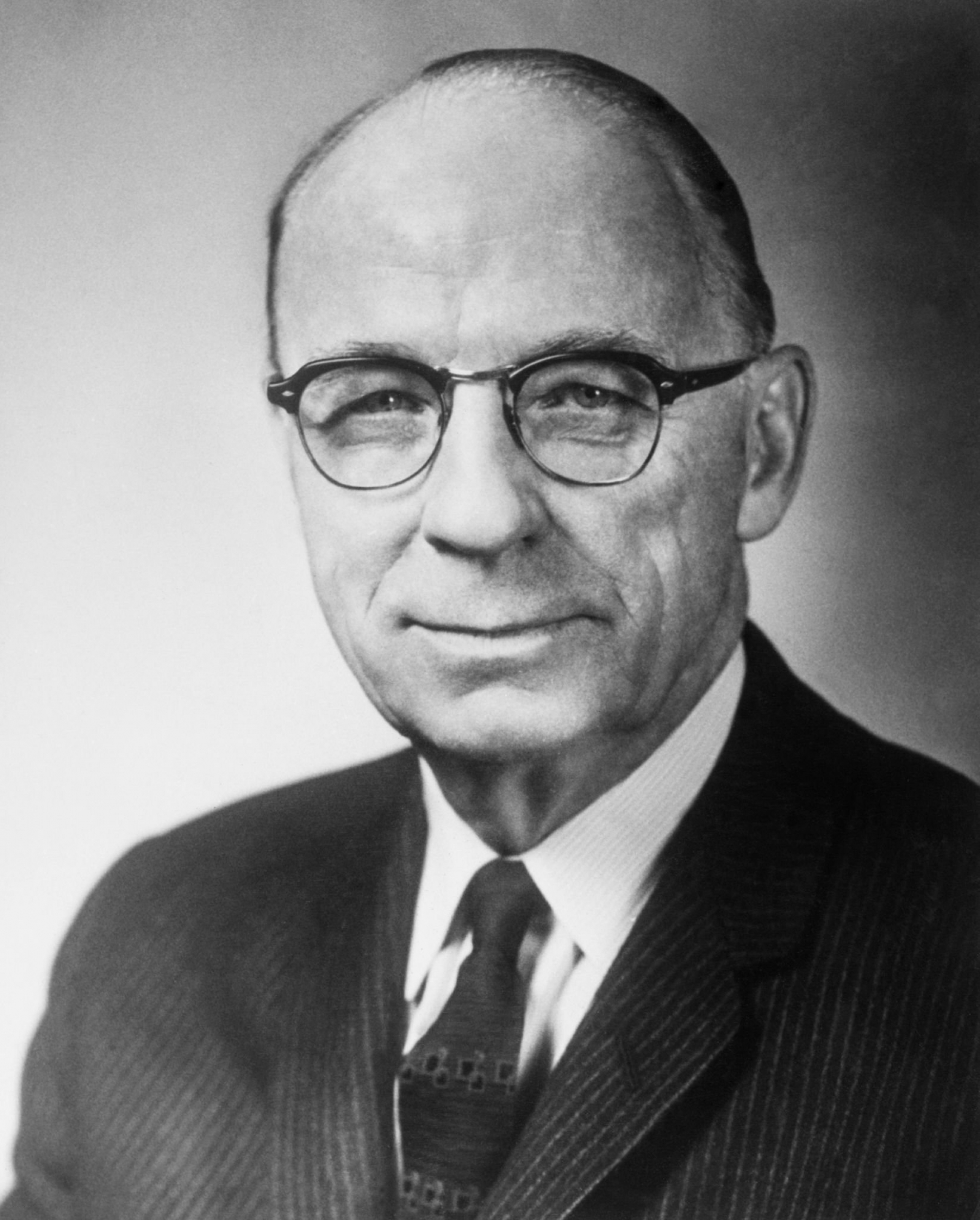

Bourke B. Hickenlooper

Bourke B. Hickenlooper | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chair of the Senate Republican Policy Committee | |

| In office January 3, 1962 – January 3, 1969 | |

| Leader | Everett Dirksen |

| Preceded by | Styles Bridges |

| Succeeded by | Gordon Allott |

| United States Senator from Iowa | |

| In office January 3, 1945 – January 3, 1969 | |

| Preceded by | Guy Gillette |

| Succeeded by | Harold Hughes |

| 29th Governor of Iowa | |

| In office January 14, 1943 – January 11, 1945 | |

| Lieutenant | Robert D. Blue |

| Preceded by | George A. Wilson |

| Succeeded by | Robert D. Blue |

| 29th Lieutenant Governor of Iowa | |

| In office January 12, 1939 – January 14, 1943 | |

| Governor | George A. Wilson |

| Preceded by | John K. Valentine |

| Succeeded by | Robert D. Blue |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Bourke Blakemore Hickenlooper July 21, 1896 Blockton, Iowa, U.S. |

| Died | September 4, 1971 (aged 75) Shelter Island, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Verna Bensch |

| Children | 2 |

| Education | Iowa State University (BA) University of Iowa (LLB) |

Bourke Blakemore Hickenlooper (July 21, 1896 – September 4, 1971) was an American attorney and politician from the U.S. state of Iowa. He was lieutenant governor from 1939 to 1943 and then the 29th Governor of Iowa from 1943 to 1945. In 1944, he won election to the first of four terms in the United States Senate, where he served until 1969.

Early life and education[]

Hickenlooper was born in Blockton in Taylor County in southwestern Iowa, an only child of a farming couple, Margaret (Blakemore) and Nathan Hickenlooper.[1][2] He attended Iowa State University, then Iowa State College in Ames, but his education was interrupted by his service in the United States Army during World War I. In April 1917, Hickenlooper enrolled in the officers' training camp at Fort Snelling, Minnesota. He was commissioned a second lieutenant and assigned to France as a battalion orientation officer.[3]

After military service, Hickenlooper early in 1919 returned to the United States. In June 1919, he received his bachelor's degree in industrial science from Iowa State. He then enrolled at the University of Iowa College of Law, earning a Bachelor of Laws in 1922.

Career[]

After graduating from law school, he practiced law in Cedar Rapids. He served in the Iowa House of Representatives from 1934 to 1937.[3] His grandfather had earlier served in the same body.[4]

Iowa politics[]

When he ran for lieutenant governor, the first time unsuccessfully in 1936, Hickenlooper told voters they could call him plain "Hick" because of the difficulty of pronouncing his name. He told a yarn about his going as a child to a drugstore in the county seat of Bedford to obtain a nickel's worth of asafetida for his mother. The druggist just gave him the asafetida, a pungent herb used in cooking, to avoid having to write out both "asafetida" and the long name "Bourke Blakemore Hickenlooper."[5]

As lieutenant governor, Hickenlooper saved a Cedar Rapids woman from drowning in the Cedar River. The extensive publicity from his rescue mission generated him much support when he ran for governor in 1942.[4]

U.S. Senate[]

In 1944, Hickenlooper unseated the Democrat Guy M. Gillette in the U.S. Senate election. As a senator from 1945 to 1969, Hickenlooper was among the most conservative and isolationist members of his party. He became the top Republican on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, serving alongside longtime Democratic chairman J. William Fulbright of Arkansas.[6] In 1967, near the end of his Senate tenure, Hickenlooper and Fulbright were instrumental in the drafting of the , the first such international agreement between the United States and the Soviet Union.[7]

Hickenlooper was a co-author of the Atomic Energy Act of 1954, which initiated the development of atomic power for peaceful uses.[8] He also chaired the Joint Congressional Atomic Energy Committee. In this capacity, Hickenlooper questioned the whereabouts of missing uranium from an AEC laboratory in Illinois and urged the removal of AEC chairman David Lilienthal, who claimed no knowledge of the incident. Though the AEC committee declined by a 9 to 8 vote to remove Lilienthal, he nevertheless resigned some six months later, having claimed that his career had been ruined by the mystery of the missing uranium.[6]

In 1958, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed Hickenlooper as a U.S. representative to the United Nations General Assembly. In 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson named him to a congressional team to oversee the elections in the Republic of South Vietnam.[5]

Hickenlooper in time became one of the most powerful Republicans in the Senate, having served from 1962 to 1969 as the Republican Policy Committee chairman. In this position, he developed an intense intraparty rivalry with fellow Midwesterner Everett McKinley Dirksen of Illinois, the Senate Republican leader from 1959 to 1969.[9] Hickenlooper voted in favor of the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960,[10][11] as well as the 24th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and the Voting Rights Act of 1965,[12][13] but voted against the Civil Rights Act of 1964,[14] and did not vote on the Civil Rights Act of 1968 or the confirmation of Thurgood Marshall to the U.S. Supreme Court.[15][16] Dirksen was working in collaboration with U.S. Senator Hubert H. Humphrey of Minnesota, the Democratic floor manager of the legislation and later Vice President of the United States from 1965 to 1969. Dirksen persuaded all but six of the Republican senators to support the 1964 measure. Hickenlooper hence joined Norris Cotton of New Hampshire, Barry M. Goldwater of Arizona, John G. Tower of Texas, Edwin L. Mechem of New Mexico, and Milward Simpson of Wyoming in voting against the bill championed by their other GOP colleagues.[17] Hickenlooper said that his opposition to civil rights legislation was based on a fear that such laws would lead to "bureaucrats snooping into every area of American life."[6]

The next year, Hickenlooper, following Dirksen's leadership, voted with other Northerners in support of the Immigration Act of 1965 thus ending the National Origins Formula of the quota system established in 1921 by emergency.[18]

Hickenlooper once told an interviewer that he particularly enjoyed campaigning for office, having so frequently been before the voters for consideration. Columnists Joseph and Stewart Alsop once said in humor that the name Bourke B. Hickenlooper is "exactly the same name an English satirist would choose for an Iowa Republican."[19]

The Mason City Globe-Gazette in Mason City noted on Hickenlooper's death that he despaired of obtaining political success because of his name. "The abbreviation used by friends [Hick] was even worse. But Hickenlooper found the secret in kidding about his last name in public, making more jokes about it than [had] his political foes."[8]

Hickenlooper Amendment[]

The proposed Hickenlooper Amendment, a rider to the 1962 foreign aid bill, would have halted aid to any country expropriating US property. The amendment was specifically aimed at Cuba, led by Fidel Castro, which had expropriated US-owned and -controlled sugar plantations and refineries.[20]

The amendment followed the seizure of three US oil companies in Cuba and Argentina. It was also in response to a ruling of the US Supreme Court, which, in effect, denied the right of an American sugar company to contest the seizure of its holdings by the Castro government.[6]

Hickenlooper viewed his amendment as guaranteeing a US businessman his day in court[how?] whenever property is seized by a foreign government. The Supreme Court's ruling, wrote Hickenlooper in 1964, "presumes that any inquiry... into the acts of a foreign state will be a matter of embarrassment to the conduct of foreign policy."[6]

The amendment was strongly opposed by the administration of President John F. Kennedy, which argued that its passage would threaten all U.S. diplomacy, particularly in Latin America. It was defeated on the Senate floor, 45 to 35.[6]

Wiley Mayne, a representative from Iowa from 1967 to 1975, said[when?] that the Senate erred in rejecting the Hickenlooper Amendment. "Had the amendment been enforced throughout the years, it would appear that we would have been in a far better position in our relations with the less developed nations and certainly... in regard to our balance of payments...."[21]

Legacy[]

On October 5, 1961, some 1200 gathered in Cedar Rapids in a ceremony to honor Hickenlooper's service to the state and the nation. Former Presidents Herbert Hoover and Dwight Eisenhower sent accolades. Many of his Senate colleagues came in person. The modest Hickenlooper replied to the tributes: "I wish that the many fine things that have been said about me could be fully accurate. Friendship has a habit of putting a little more glitter on a man than is actually there."[5]

Hickenlooper was the longest-serving popularly-elected U.S. senator from Iowa until Charles Grassley surpassed Hickenlooper's four terms, with his fifth election in 2004, his sixth in 2010 and his seventh in 2016. William B. Allison served thirty-five years, but his service came while the state legislatures chose senators.[5]

Hickenlooper's name was on an Iowa ballot 19 times, including primaries and general elections; he won 17 of his races.[22]

He lost his first attempt on the ballot in 1932 in a bid for county attorney of Linn County in eastern Iowa. He lost the lieutenant governor's race in 1936. He also lost the 1938 Republican primary for lieutenant governor, but the nominee chosen, Harry B. Thompson of Muscatine, withdrew, and the Republican state convention instead placed Hickenlooper on the general election ballot. He never lost another election, his final victory being the 1962 Senate election.[22]

The Cedar Rapids Gazette described Hickenlooper as having had "a keen sense of humor, [was] a staunch defender of the private enterprise system, an advocate of a farm economy unfettered by government controls, and an opponent of excessive spending both at home and abroad.... Indeed, his was an enviable record that will serve as an inspiration to all Iowans with political aspirations."[22]

Hickenlooper's Senate colleague, John C. Stennis, a Mississippi Democrat, said that he regarded Hickenlooper "as one of the most valuable men we had in this body. I never saw him go off the deep end on anything without thinking the matter out, and I never saw him lose his patience though I have seen him under a lot of pressure...."[19]

Personal life[]

Hickenlooper retired to his home in Chevy Chase, Maryland, where he and his wife had lived since he came to Washington in 1945. He had been planning to relocate to an apartment the month he died. He complained of abdominal pains and died shortly thereafter over the Labor Day weekend in 1971, while he was visiting friends, the Henry R. Holthusens, in Shelter Island, New York.[4]

Hickenlooper and his wife, the former Verna Bensch, who preceded him in death by some nine months, are interred in a mausoleum in the Cedar Memorial Cemetery in Cedar Rapids.[citation needed] The couple had two children, David Hickenlooper, who resided in Bloomfield, Iowa, at the time of his parents' death, and Jane H. Oberlin, the wife of Russell Oberlin of Des Moines.[5]

Hickenlooper's grand-nephew is former Governor of Colorado and current U.S. Senator John Hickenlooper.[23]

References[]

- ^ "Hickenlooper, Bourke Blakemore – The Biographical Dictionary of Iowa -The University of Iowa". uipress.lib.uiowa.edu.

- ^ "Taylor County, Iowa: Julia Johnson obits Hickenlooper file". iagenweb.org.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Biographical Directory of the American Congress

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Memorial Addresses and Other Tributes in the Congress of the United States on the Life and Contributions of Bourke B. Hickenlooper, p. 4

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Iowa State Senate Memorial Resolution", February 29, 1972, cited in Memorial Addresses and Other Tributes in the Congress of the United States on the Life and Contributions of Bourke B. Hickenlooper (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1972), pp. vii–viii

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Memorial Addresses and Other Tributes in the Congress of the United States on the Life and Contributions of Bourke B. Hickenlooper, p. 5

- ^ Memorial Addresses and Other Tributes in the Congress of the United States on the Life and Contributions of Bourke B. Hickenlooper, p. 27

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mason City Globe-Gazette, Mason City, Iowa, September 8, 1971

- ^ "Everett Dirksen and the 1964 Civil Rights Act". lib.niu.edu. Retrieved June 24, 2011.

- ^ "HR. 6127. CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1957". GovTrack.us.

- ^ "HR. 8601. PASSAGE OF AMENDED BILL".

- ^ "S.J. RES. 29. APPROVAL OF RESOLUTION BANNING THE POLL TAX AS PREREQUISITE FOR VOTING IN FEDERAL ELECTIONS". GovTrack.us.

- ^ "TO PASS S. 1564, THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT OF 1965".

- ^ "HR. 7152. PASSAGE".

- ^ "TO PASS H.R. 2516, A BILL TO PROHIBIT DISCRIMINATION IN SALE OR RENTAL OF HOUSING, AND TO PROHIBIT RACIALLY MOTIVATED INTERFERENCE WITH A PERSON EXERCISING HIS CIVIL RIGHTS, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES".

- ^ "CONFIRMATION OF NOMINATION OF THURGOOD MARSHALL, THE FIRST NEGRO APPOINTED TO THE SUPREME COURT". GovTrack.us.

- ^ "Who Opposed the Civil Rights Act of 1964?". capitalgainsandgames.com. Retrieved June 24, 2011.

- ^ "TO PASS H.R. 2580, IMMIGRATION AND NATIONALITY ACT AMENDMENTS". govtrack.us. Retrieved July 27, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Memorial Addresses and Other Tributes in the Congress of the United States on the Life and Contributions of Bourke B. Hickenlooper, p. 6

- ^ Cynthia Clark Northrup, Elaine C. Prange Turney, Encyclopedia of Tariffs and Trade in U.S. History: The encyclopedia

- ^ Memorial Addresses and Other Tributes in the Congress of the United States on the Life and Contributions of Bourke B. Hickenlooper, p. 23

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Editorial, Cedar Rapids Gazette, September 6, 1971

- ^ "The Spot: Denver politics are about to take center stage and what's coming in 2019 for marijuana". The Denver Post. 2018-12-06. Retrieved 2021-03-11.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bourke Hickenlooper. |

- United States Congress. "Bourke B. Hickenlooper (id: H000559)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Biographical notes and descriptions of archive of Hickenlooper's congressional papers and notes

- A film clip "Longines Chronoscope with Sen. Bourke B. Hickenlooper (August 27, 1951)" is available at the Internet Archive

- Appearances on C-SPAN

| show |

|---|

- 1896 births

- 1971 deaths

- 20th-century American politicians

- United States Army personnel of World War I

- Governors of Iowa

- Hickenlooper family

- Iowa lawyers

- Iowa Republicans

- Iowa State University alumni

- Lieutenant Governors of Iowa

- Maryland Republicans

- Members of the Iowa House of Representatives

- Old Right (United States)

- People from Chevy Chase, Maryland

- People from Taylor County, Iowa

- Politicians from Cedar Rapids, Iowa

- Republican Party state governors of the United States

- Republican Party United States senators

- United States Army officers

- United States senators from Iowa

- University of Iowa College of Law alumni