Burmese amber

Burmese amber, also known as Burmite or Kachin amber, is amber from the Hukawng Valley in northern Myanmar. The amber is dated to around 99 million years old, during the earliest part of the Cenomanian age of the Late Cretaceous. The amber is of significant palaeontological interest due to the diversity of flora and fauna contained as inclusions, particularly arthropods including insects and arachnids but also birds, lizards, snakes, frogs and fragmentary dinosaur remains. The amber has been known and commercially exploited since the first century AD, and has been known to science since the mid-nineteenth century. Research on the deposit has attracted controversy due to its alleged role in funding internal conflict in Myanmar and hazardous working conditions in the mines where it is collected.

Geological context, depositional environment and age[]

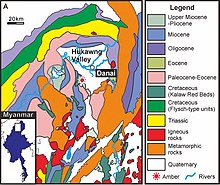

The amber is found within the Hukawng Basin, a large Cretaceous-Cenozoic sedimentary basin within northern Myanmar. The strata have undergone folding and faulting. The Hukawng basin is part of the larger Myanmar Central Basin, a N-S orientated synclinal basin extending to the Gulf of Martaban to the south. The basin is considered to be a part of the West Burma Block or Burma Terrane, which has a debated tectonic history, it is considered to be associated with the concepts of the Cimmeria and Sibumasu terranes. The block was part of Gondwana during at least the Early Paleozoic, but the timing of rifting is very uncertain, with estimates ranging from the Devonian to Early Cretaceous. It is also disputed whether the block had accreted onto the Asian continental margin by the time of the amber deposition.[1] Some members of the flora and fauna have Gondwanan affinities[2] A recent paleomagnetic reconstruction finds that the Burma Terrane formed an island land mass in the Tethys Ocean during the Mid Cretaceous at a latitude around 5-10 degrees south of the equator.[3]

At Noije Bum, located on a ridge, amber is found within fine grained clastic rocks, typically medium to greyish green in colour, resulting from the constituent grains being black, yellow, grey and light green. The fine grained rocks are primarily fine to very fine grained sandstone, with beds of silt and shale and laterally persistent thin (1–2 mm thick) coal horizons. Massive micritic limestone interbeds of 6-8 centimetre thickness, often containing coalified plant material also occur. This facies association is typically around 1 metre thick and typically thinly bedded and laminated. Associated with the fine grained facies is a set of medium facies primarily consisting of medium to fine grained sandstones also containing thin beds of siltstone, shale and conglomerate, alongside a persistent conglomerate horizon. A specimen of the ammonite Mortoniceras has been found in a sandstone bed 2 metres above the amber horizon, alongside indeterminate gastropods and bivalves.[4] Lead-uranium dating of zircon crystals of volcanic clasts within the amber bearing horizons has given a maximum age of 98.79 ± 0.62 million years ago (Ma), making the deposit earliest Cenomanian in age.[5] Unpublished data by Wang Bo on other layers suggests an age range of deposition of at least 5 million years.[6] The amber does not appear to have undergone significant transport since hardening or be redeposited. The strata at the site are younging upwards, striking north north-east and dipping 50-70 degrees E and SE north of the ridge and striking between south south-east and south-east and dipping 35-60 degrees south-west south of the ridge, suggesting the site is on the northwest limb of a syncline plunging to the northeast. A minor fault with a conspicuous gouge zone was noted as present, though it appeared to have no significant displacement.[4] Several other localities are known, including the colonial Khanjamaw and the more recent Inzutzut, Angbamo, and Xipiugong sites, within the vicinity of Tanai. The Hkamti site SW of the Hukawng basin has been determined to be significantly older, dating to the early Albian around ca. 110 Ma and is therefore considered distinct.[7]

Paleoenvironment[]

The Burmese amber paleoforest is considered to have been a tropical rainforest, situated near the coast, where resin was subsequently transported into a shallow marine environment. The shell of a dead juvenile Puzosia (Bhimaites) species ammonite, four marine gastropod shells (including Mathilda) and littoral or supralittoral isopods entombed in a piece of amber with shell sand,[8] along with growth of Isocrinid crinoids, corals and oysters on the surface of some amber pieces indicate marine conditions for final deposition.[9] Additionally pholadid (piddock) bivalve borings into amber specimens along with at least one pholadid which became trapped was interpreted to show that the resin was still fresh and unhardened when it was being moved into the tidal areas.[10] However, the phloladids in question, belonging to the extinct genus , were later intepreted as a freshwater species, and the presence of numerous freshwater insects suggests that the initial environment of deposition was a downstream estuarine to freshwater section of a river, with the forests extending across coastal rivers, river deltas, lakes, lagoons, and coastal bays.[11]

The amber itself is primarily disc-shaped and flattened along the bedding plane, and is typically reddish brown, with the colour ranging from shades of yellow to red. The opacity of the amber ranges from clear to opaque. Many amber pieces have thin calcite veins that are typically less than 1 mm (0.04 in), but up to 4–5 mm (0.16–0.20 in) thick. The number and proportion of veins in a piece of amber varies significantly, in some pieces veins are virtually absent, while others are described as being "packed with veinlets"[4] The amber is considered to be of coniferous origin, with a likely araucarian source tree, based on spectroscopic analysis and wood fragment inclusions,[12] though a pine origin has also been suggested.[13]

Fauna and flora[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2021) |

The list of taxa is extraordinarily diverse, with over 42 classes, 108 orders, 569 families, 1017 genera and 1379 species described as of the end of 2019, with over 300 species described in 2019 alone, the vast majority (94%) of which are arthropods. A complete list of taxa up until the end of 2018 can be found in Ross 2018[14] And a supplement covering most of 2019 can be found in Ross 2019b.[15] For the sake of brevity, a complete list of taxa is not given here, and the classification is mostly at family level. For a more complete list of taxa, see Paleobiota of Burmese amber.

Invertebrates[]

Well over 1000 species of invertebrates are known from the deposit, including, notably the oldest members of Palpigradi (Electrokoenenia)[16] and Schizomida ()[17] the oldest Velvet worm (Cretoperipatus)[18] and the only known fossil members of Mesothelae and Ricinulei since the Paleozoic. Chimerarachne is a unique stem spider still possessing a tail, with similar forms only known from the Paleozoic.

Arachnids[]

Araneae[]

Forty-four families of spiders are known from the Burmese amber, including: Archaeidae, †, †, †Burmathelidae, Clubionidae, Corinnidae, †Cretaceothelidae, Deinopidae, Dipluridae, †, †Fossilcalcaridae, Hersiliidae, Hexathelidae, †Lagonomegopidae, Leptonetidae, Liphistiidae, †, †Mongolarachnidae, Mysmenidae, Ochyroceratidae, Oecobiidae, Oonopidae, Oxyopidae, Palpimanidae, †, Pholcidae, †, †, †, †, Psechridae, Psilodercidae, Salticidae, Segestriidae, Telemidae, Tetrablemmidae, Tetragnathidae, Theridiosomatidae, Theridiidae, Thomisidae, Uloboridae and †.

Acariformes[]

Twenty families of acariformes are known from the Burmese amber, including: Anystidae, , Bdellidae, Caeculidae, Cheyletidae, , Eremaeidae, Erythraeidae, Eupodidae, Gymnodamaeidae, Malaconothridae, Microtrombidiidae, Neoliodidae, Oribatellidae, Oribotritiidae, , Smarididae, , Trombidiidae and Tuckerellidae.

Opiliones[]

Nine families of opiliones are known from the Burmese amber, including: , Epedanidae, †, †,†, ? Sclerosomatidae, Stylocellidae and .

Pseudoscorpiones[]

Twelve families of pseudoscorpions are known from the Burmese amber, including: Atemnidae, Cheiridiidae, Cheliferidae, Chernetidae, Chthoniidae, Feaellidae, Garypinidae, Ideoroncidae, Neobisiidae, and Withiidae.

Scorpiones[]

Seven families of scorpions are known from the Burmese amber, including: Buthidae, Chaerilidae, †, †, †, † and †.

Parasitiformes[]

Five families of parasitiformes are known from the Burmese amber, including: Argasidae, †Deinocrotonidae, Ixodidae, Opilioacaridae and Polyaspididae.

Schizomida[]

One genus of schizomida is known from the Burmese amber: , which belongs to Hubbardiidae

Palpigradi[]

One genus of palpigradi is known: Electrokoenenia, which belongs to Eukoeneniidae

Amblypygi[]

Two genera of Amblypygi are known: and which do not belong to any extant family.

Solfugae[]

One genus of camel spider is known: , which does not belong to any extant family.

Thelyphonida[]

Two genera of whip scorpion are known: , which belongs to Thelyphonidae and , which does not belong to any extant family.

Ricinulei[]

Three genera of Ricinulei are known: , ? (an otherwise Carboniferous taxon) and , none of which belong to extant families

Myriapoda[]

Sixteen families of Myriapods are known, including: Anthroleucosomatidae, †, Tingupidae, Glomeridellidae, Andrognathidae, Paradoxosomatidae, Polydesmidae, Polyxenidae, Synxenidae, Polyzoniidae, Siphoniulidae, Siphonophoridae, Siphonorhinidae, Zephroniidae, Cambalidae, Scolopendrellidae and †Burmanopetalidae.

Entognatha[]

Eight families of Entognathans are known, including: Campodeidae, Japygidae, Isotomidae, †Praentomobryidae, Tomoceridae, Neanuridae, Odontellidae and Sminthuridae.

Insects[]

Incertae sedis[]

A species of the enigmatic long legged insect Chresmoda is known.[19]

Archaeognatha[]

Two families of archaeognathans are known from the Burmese amber: Machilidae and Meinertellidae

Zygentoma[]

One family of Zygentoman is known: Lepismatidae

Ephemeroptera[]

Seven families of mayfly are known: †, Baetidae, Ephemeridae, Heptageniidae, †, Isonychiidae, Prosopistomatidae.

Odonata[]

Twenty families of odonatan are known from the Burmese amber, including: Aeshnidae, †, †, †, †, †, Calopterygidae, Coenagrionidae, , , Gomphidae, Hemiphlebiidae, Libellulidae, Lindeniidae, Megapodagrionidae, †, †, Perilestidae, Platycnemididae, Platystictidae.

Hymenopterans[]

Over fifty families of hymenopterans have been described beginning with the papers of Cockerell who described a group of Bethylidae and Aulacidae species between 1917 and 1920. The monotypic family Melittosphecidae is only known from the Burmese amber species Melittosphex burmensis and eight species belonging to Aptenoperissus of the monotypic family Aptenoperissidae are also known. Originally described as an Aneuretinae ant Burmomyrma rossi was moved to the extinct Chrysidoidea family .[20] A number of Formicidae species known, belonging to Baikuris (indet) Camelomecia janovitzi, Ceratomyrmex ellenbergeri, 11 species of Gerontoformica, 3 species of Haidomyrmex, Linguamyrmex vladi, 2 species of Zigrasimecia, , , , and . Other families include Ampulicidae, Braconidae, Cephidae, Ceraphronidae, Chalcididae, Chrysididae, Crabronidae, Diapriidae, Dryinidae, Embolemidae, Evaniidae, Gasteruptiidae, Heloridae, Ichneumonidae, Megalyridae, Megaspilidae, Mymaridae, Mymarommatidae, Pelecinidae, Platygastridae, Rhopalosomatidae. Rotoitidae, Sapygidae, Scelionidae, Sclerogibbidae, Scolebythidae, Sepulcidae, Sierolomorphidae, Siricidae, Sphecidae, Stephanidae, Tiphiidae, Vespidae, Xiphydriidae, †Angarosphecidae, †Aptenoperissidae, †, †, †, †, †Diversinitidae, †, †Gallorommatidae, †, †, †Plumalexiidae, †Maimetshidae, †, †, †Praeaulacidae, †Proterosceliopsidae, †Serphitidae, †Spathiopterygidae, † and several incertae sedis taxa.

Dipterans[]

Forty-seven families of dipterans are known from the Burmese amber, including: Acroceridae, Anisopodidae, Apsilocephalidae, Apystomyiidae, Asilidae, Atelestidae, Blephariceridae, Bombyliidae, Cecidomyiidae, Ceratopogonidae, Chaoboridae, Chironomidae, Corethrellidae, Culicidae, Diadocidiidae, Dolichopodidae, Empididae, Hybotidae, Keroplatidae, Limoniidae, Lygistorrhinidae, Mycetophilidae, Mythicomyiidae, Nemestrinidae, Phoridae, Pipunculidae, Platypezidae, Psychodidae, Ptychopteridae, Rachiceridae, Rhagionidae, Scatopsidae, Sciaridae, Stratiomyidae, Tabanidae, Tanyderidae, Tipulidae, , Xylomyidae, †Cascopleciidae, †, †Eremochaetidae, †, †, †Rhagionemestriidae, †Tethepomyiidae, †Zhangsolvidae and several incertae sedis taxa.

Coleopterans[]

Over ninety families of coleopterans are known from the Burmese amber, including: Aderidae, Anthicidae, Anthribidae, †, Belidae, Boganiidae, Bostrichidae, Brachypsectridae, Buprestidae, Cantharidae, Carabidae, Caridae, Cerambycidae, Cerophytidae, Cerylonidae, Chrysomelidae, Ciidae, Clambidae, Cleridae, Cucujidae, Cupedidae, Curculionidae, Cyclaxyridae, Dascillidae, Dermestidae, Drilidae, Dytiscidae, Elateridae, Elmidae, Endomychidae, Eucinetidae, Eucnemidae, Geotrupidae, Glaresidae, Gyrinidae, Heteroceridae, Histeridae, Hybosoridae, Hydraenidae, Hydrophilidae, Ithyceridae, Jacobsoniidae, Kateretidae, Laemophloeidae, Lampyridae, Latridiidae, Leiodidae, Lepiceridae, Lucanidae, Lycidae, Lymexylidae, Melandryidae, Meloidae, Melyridae, †Mesophyletidae, Micromalthidae, Monotomidae, Mordellidae, †Mysteriomorphidae, Nemonychidae, Nitidulidae, Oedemeridae, Ommatidae, Passalidae, †, †, Passandridae, Phloeostichidae, Prostomidae, Psephenidae, Ptiliidae, Ptinidae, Ptilodactylidae, Ripiphoridae, Rhysodidae, Salpingidae, Scarabaeidae, Scirtidae, Scraptiidae, Silphidae, Silvanidae, Smicripidae, Sphaeriusidae, Staphylinidae, Tenebrionidae, Tetratomidae, Thanerocleridae, Throscidae, Trogidae, Trogossitidae and Zopheridae.

Neuroptera[]

Over twenty families of neuropterans are known from the Burmese amber, including: †, Ascalaphidae, †Babinskaiidae, Berothidae, Chrysopidae, Coniopterygidae, †, Dilaridae, †Dipteromantispidae, Hemerobiidae, Ithonidae, Kalligrammatidae, Mantispidae, †Mesochrysopidae, Myrmeleontidae, Nemopteridae, Nevrorthidae, Nymphidae, Osmylidae, Psychopsidae, Rachiberothidae, Sisyridae and several incertae sedis taxa.

Hemiptera[]

Over sixty families of hemipterans are known from the Burmese amber, including: Achilidae, †Albicoccidae, Aleyrodidae, Aphrophoridae, Aradidae, †Berstidae, †Burmacoccidae, †, Callaphididae, Cercopidae, Cicadellidae, Cicadidae, Cimicidae, Cixiidae, Coccidae, Coreidae, Cydnidae, Dictyopharidae, Dipsocoridae, †, Enicocephalidae, Fulgoridae, Gelastocoridae, Gerridae, †, Hydrometridae, Issidae, †, †Juraphididae, †, Kinnaridae, †, †, Leptopodidae, †, †, Margarodidae, Matsucoccidae, †Mimarachnidae, †, Miridae, Monophlebidae, Naucoridae, Nabidae, †, Ochteridae, Ortheziidae,†, †Parvaverrucosidae, †Perforissidae, †, †Procercopidae, Pseudococcidae, , Schizopteridae, †Sinoalidae, †, Tettigarctidae, Tingidae, Tropiduchidae, , Veliidae, †, Xylococcidae, †, †Yuripopovinidae and several incertae sedis taxa such as , formerly believed to be an ectoparasite but since determined to be a basal scale insect.[21]

Dictyoptera[]

Twenty one families of dictyopterans are known from the Burmese amber, including: Blaberidae, †Blattulidae, Blattidae, †, Corydiidae, Ectobiidae, †, †Liberiblattinidae, †Alienopteridae, †Manipulatoridae †Umenocoleidae , Nocticolidae, † Termites (†Archeorhinotermitidae, Hodotermitidae, Stolotermitidae, Termitidae and Mastotermitidae) and mantid .

Mecoptera[]

Five families of mecopteran are known, including: Bittacidae, Meropeidae, , †Pseudopolycentropodidae and †Aneuretopsychidae.

Psocoptera[]

Ten families of psocopteran are known, including: †Archaeatropidae, Compsocidae, †Empheriidae, Liposcelididae, Manicapsocidae, Pachytroctidae, Prionoglarididae, Psyllipsocidae, Sphaeropsocidae and Trogiidae.

Orthoptera[]

Seven families of orthopteran are known, including: †Elcanidae, Gryllidae, Mogoplistidae, Ripipterygidae, Tetrigidae, Tettigoniidae and Tridactylidae

Trichoptera[]

Eight families of trichopteran are known, including: Calamoceratidae, †Dysoneuridae, Helicopsychidae, Hydroptilidae, Odontoceridae, Philopotamidae, Polycentropodidae and Psychomyiidae.

Dermaptera[]

Five families of dermapteran are known, including: Anisolabididae, Diplatyidae, Labiduridae and Pygidicranidae.

Embioptera[]

Four families of embiopteran are known, including: Clothodidae, Oligotomidae, and †.

Notoptera[]

One species of notopteran is known, a nymph ice crawler (Grylloblattidae) .[22]

Strepsiptera[]

Two families of strepsipteran are known, † and †

Lepidoptera[]

Six families of lepidopteran are known, including: Agathiphagidae, Douglasiidae, Gelechiidae, Gracillariidae, Lophocoronidae and Micropterigidae.

Megaloptera[]

One species of megalopteran is known, of the family Sialidae.

Phasmatodea[]

Four families of phasmatodean are known: †, Phasmatidae. † and Timematidae

Thysanoptera[]

Five families of thrips are known, including: Aeolothripidae, Melanthripidae, †, Thripidae and Stenurothripidae.

Plecoptera[]

Two families of stoneflies are known, Perlidae and †.

Raphidioptera[]

One family of Raphidiopteran is known, †Mesoraphidiidae.

†Tarachoptera[]

One family of Tarachopteran is known: †Tarachocelidae

†Permopsocida[]

One family of Permopsocidan is known: †Archipsyllidae

Zoraptera[]

Multiple species of Zorotypus and the monotypic genus are known.

Nematoda[]

Five families of nematodes are known, including: Cosmocercidae, Heterorhabditidae, Mermithidae, Thelastomatidae, Aphelenchoididae

Nematomorpha[]

One genus of nematomorph is known: (Chordodidae, Gordioidea)

Mollusca[]

Aside from the previously mentioned ammonites and marine gastropod shells, Seven families of terrestrial gastropod are known: Diplommatinidae, Pupinidae, Achatinidae, Punctidae, Valloniidae, Assimineidae and Cyclophoridae[23][24][25]

Vertebrates[]

While the deposit is well known for invertebrate inclusions, some vertebrate inclusions have been found as well. One of the more notable discoveries was a well preserved theropod dinosaur tail, with preserved feathers.[26] As well as fossils of enantiornithine birds including juveniles[27][28] and partial wings and preserved feet,[29][30][31][32] including a diagnostic taxon, Elektorornis.[33] A complete skull of the bizarre avialan or lizard Oculudentavis is known.[34] Electrorana is a well preserved frog known from the amber.[35] Other notable specimens include an embryonic snake.[36] Several specimens of lizard have been described from the deposit[37] including a gecko with preserved toe pads (Cretaceogekko).[38] and a miniaturised (~2 cm) long possible stem-anguimorph ()[39]

One of the "lizard" specimens was initially described to be a chamelonid, actually turned out to be an albanerpetonid amphibian.[40] This was described in 2020 as the new genus and species Yaksha perettii.[41]

Flora[]

Angiosperms[]

Eleven species of Angiosperm are known in nine genera, including members of Cornaceae, Cunoniaceae, Lauraceae, ?Monimiaceae and Laurales incertae sedis. Poales incertae sedis and Angiosperm incertae sedis.

Bryopsida[]

Two genera of Bryopsida in the separate orders Dicranales and Hypnodendrales

Jungermanniopsida[]

Three families of Jungermanniopsida are known, Frullaniaceae, , Radulaceae.

Pinophyta[]

Two families of Pinopsida are known: Araucariaceae and Cupressaceae including Metasequoia.

Pteridopsida[]

Five families of Pteridopsidan are known: Cystodiaceae, Dennstaedtiaceae, Lindsaeaceae, Pteridaceae, Thyrsopteridaceae, and several genera of Polypodiales incertae sedis.

Amoebozoa[]

Myxogastria[]

Sporocarps of extant myxogastrid slime mould genus Stemonitis are known.[42]

Dictyostelia[]

A possible dictyostelid has been described.[43]

History[]

The amber is apparently referred to in ancient Chinese sources as originating from Yunnan Province as early as the first century AD according to the Book of the Later Han and trade with China had been ongoing for centuries. This has been confirmed by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis of amber artifacts from the Eastern Han Dynasty (25 - 220 CE).[44] It was first mentioned in European sources by the Jesuit Priest Álvaro Semedo who visited China in 1613, it was described as being "digged out of mines, and sometimes in great pieces, it is redder than our amber though not so cleane".[45] The locality itself has been known to European explorers since the 1800s with visitation to the Hukawng Valley by Simon Fraser Hannay in 1836–1837.[46][47] At that time the principle products of the valley mines were salt, gold, and amber, with the majority of gold and amber being bought by Chinese traders. Hannay visited the amber mines themselves on March 21, 1836, and he noted that the last three miles to the mines were marked with numerous abandoned pits, up to 15 ft (4.6 m) in depth, where amber had been dug in the past. The mining had moved over the hill to a series of 10 pits but no visible amber was seen, suggesting that miners possibly hid the amber found that day before the party arrived. Mining was being performed manually at the time through the use of sharpened bamboo rods and small wooden shovels. Finer pieces of amber were recovered from the deeper pits, with clear yellow being recovered from depths of 40 ft (12 m) The recovered amber was bought with silver or often exchanged for jackets, hats, copper pots, or opium among other goods. mixed and lower quality amber was sold from around 1/ ticals to 4 rupees per seer. Pieces that were considered high quality or fit or use as ornamentation were described as expensive and price varied depending on clarity and color. Women of the valley were noted to wear amber earrings as part of their jewelry.[46] In 1885 the Konbaung dynasty was annexed to the British Raj and a survey of the area was conducted by Dr. Fritz Noetling on behalf of the Geological Survey of India.[45] The final research before Burmese independence in 1947 was conducted by Dr. H.L. Chhibber in 1934, who provided the most detailed description of Burmite occurrences.[45]

History of research[]

The first research on the inclusions in the Burmese amber was published in 1916 by Theodore Dru Alison Cockerell, who initially concluded that the amber was Miocene in age. However, he subsequently noted the archaic nature of the insects, and concluded that the amber must be older.[45]

Modern exploitation and controversy[]

Leeward Capital Corp, a small Canadian mining firm, controlled the deposit from the mid 1990s to c. 2000, though the history of exploitation during the 2000s is obscure. The Kachin Independence Army (KIA) controlled the area during the early to mid 2010's. During the early 2010s, production rapidly increased. The working conditions at the mines have been described as extremely unsafe, down 100 m (330 ft) deep pits barely wide enough to crawl through, with no accident compensation.[6] The Kachin Independence army controlled amber export via numerous licenses, taxes, restrictions on movement of labor, and enforced auctions.[48] The main amber market in Myanmar is Myitkyina. Most amber is smuggled into China, primarily for jewelry, with estimates of around 100 tonnes passing through to the main market of Tengchong, Yunnan in 2015, with an estimated value between five and seven billion yuan. Burmese amber was estimated to make up 30% of Tenchong's gemstone market (the rest being Myanmar Jade), and was declared one of the cities eight main industries by the local government.[49] The presence of calcite veins are a major factor in determining the gem quality of pieces, with pieces with a large number of veins having significantly lower value.[4] In June 2017 the Tatmadaw seized control of the mines from the KIA.[50]

Sales of amber were alleged to help fund the Kachin conflict by various news organisations in 2019.[51][52] Interest in this discussion rose in March 2020 after the highly publicised description of Oculudentavis, which made the cover of Nature.[53] On April 21, 2020 the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (SVP) published a letter of recommendation to journal editors asking for “a moratorium on publication for any fossil specimens purchased from sources in Myanmar after June 2017 when the Myanmar military began its campaign to seize control of the amber mining”.[54] On April 23, 2020 Acta Palaeontologica Polonica stated that it would not accept papers on Burmese amber material collected from 2017 onwards, after the Burmese military took control of the deposit, requiring "certification or other demonstrable evidence, that they were acquired before the date both legally and ethically".[55] On May 13, 2020, the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology published an editorial stating that it would no longer consider papers based whole or in part on Burmese amber material, regardless of whether in historic collections or not.[56] On 30 June 2020, a statement from the International Palaeoentomological Society was published in response to the SVP, criticising the proposal to ban publishing on Burmese amber material.[57] In August 2020, a comment from over 50 authors was published in PalZ responding to the SVP statement. The authors disagreed with the proposal of a moratorium, describing the focus on the Burmese amber as "arbitrary" and that "The SVP’s recommendation for a moratorium on Burmese amber affects fossil non-vertebrate research much more than fossil vertebrate research and clearly does not represent this part of the palaeontological community."[58]

The conclusion that Burmese amber funded the Tatmadaw was disputed by George Poinar and Sieghard Ellenberger, who found that the supply of amber collapsed after the 2017 takeover of the mines by the Tatmandaw, and that most of the current circulation of amber in Chinese markets was extracted prior to 2017.[59] A story in Science in 2019 stated: "Two former mine owners, speaking through an interpreter in phone interviews, say taxes have been even steeper since government troops took control of the area. Both shut their mines when they became unprofitable after the government takeover, and almost all deep mines are now out of business, dealers here corroborate. Only shallow mines and perhaps a few secret operations are still running."[6] There were around 200,000 miners working in the Hukawng valley mines prior to the takeover by the Tatmadaw, which shrunk to 20,000 or less after the military operations.[48] Adolf Peretti, a gemologist who owns a museum with Burmese amber specimens, noted that the 2017 cutoff suggested by the SVP does not take into account that the export of Burmese amber prior to 2017 was also funding internal conflict in Myanmar due to the control by the KIA.[48] Much of the amber cutting since 2017 has been done in internally displaced person camps, under humanitarian and non-conflict conditions.[48]

Other Myanmar ambers[]

Other deposits of amber are known from several regions in Myanmar, with noted deposits in the Shwebo District of the Sagaing Region, from the Pakokku and Thayet districts of Magway Region and the Bago District of the Bago Region.[60][47] Unlike the Hukawng deposit, none of these sources have produce notable quantities of amber.[citation needed]

Tilin amber[]

A 2018 study on an amber deposit from Tilin in central Myanmar indicated that deposit to be 27 million years younger than the Hukawng deposit, dating to approximately 72 million years old, placing it in the latest Campanian age. The deposit was associated with an overlying tuffaceous layer, and underlying nodules of brown sandstone yielded remains of the ammonite Sphenodiscus. Within a number of arthropod specimens were described though much more poorly preserved than specimens in the Hukawng amber. These include members of Hymenoptera (Braconidae, Diapriidae, Scelionidae) Diptera (Ceratopogonidae, Chironomidae) Dictyoptera (Blattaria, Mantodea) planthoppers, Berothidae and bark lice (Lepidopsocidae) as well as extant ant subfamilies Dolichoderinae and tentatively Ponerinae, as well as fragments of moss.[61]

Hkamti amber[]

The Hkamti site is located ca. 90 km southwest of the Angbamo site and predominantly consists of limestone, interbedded with mudstone and tuff, the amber is found within the unconsolidated mudstone/tuff layers. A crinoid was found attached to one amber specimen, alongside marine plant remains in the surrounding sediment, indicating deposition in a shallow marine setting. The amber is generally red-brown, and yellow colouration is rare, the amber is generally found as angular clasts, indicating short transport distance and is more brittle than other northern Myanmar ambers. Zircon dating has constrained the age of the deposit to the early Albian, c. 110 Ma, significantly older than the dates obtained from other deposits. Fauna found within the amber includes: Archaeognatha, Diplopoda, Coleoptera, Araneae, Trichoptera, Neuroptera, Psocodea, Isoptera Diptera, Orthoptera, Pseudoscorpionida, Hymenoptera and Thysanoptera.[7]

References[]

- ^ Metcalfe, Ian (June 2017). "Tectonic evolution of Sundaland". Bulletin of the Geological Society of Malaysia. 63: 27–60. doi:10.7186/bgsm63201702.

- ^ Poinar, George (2018-03-09). "Burmese amber: evidence of Gondwanan origin and Cretaceous dispersion". Historical Biology: 1–6. doi:10.1080/08912963.2018.1446531. ISSN 0891-2963. S2CID 90373037.

- ^ Westerweel, Jan; Roperch, Pierrick; Licht, Alexis; Dupont-Nivet, G.; Win, Zaw; Poblete, Fernando; Ruffet, Gilles; Swe, Hnin; Thi, Myat; Aung, Day (2019-10-01). "Burma Terrane part of the Trans-Tethyan Arc during collision with India according to palaeomagnetic data". Nature Geoscience. 12 (10): 863–868. Bibcode:2019NatGe..12..863W. doi:10.1038/s41561-019-0443-2. PMC 6774779. PMID 31579400.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Cruickshank, R.D; Ko, Ko (February 2003). "Geology of an amber locality in the Hukawng Valley, Northern Myanmar". Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 21 (5): 441–455. Bibcode:2003JAESc..21..441C. doi:10.1016/S1367-9120(02)00044-5.

- ^ Shi, Guanghai; Grimaldi, David A.; Harlow, George E.; Wang, Jing; Wang, Jun; Yang, Mengchu; Lei, Weiyan; Li, Qiuli; Li, Xianhua (October 2012). "Age constraint on Burmese amber based on U–Pb dating of zircons". Cretaceous Research. 37: 155–163. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2012.03.014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Sokol, Joshua (2019-05-23). "Fossils in Burmese amber offer an exquisite view of dinosaur times—and an ethical minefield". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aay1187. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Xing, Lida; Qiu, Liang (November 2020). "Zircon U Pb age constraints on the mid-Cretaceous Hkamti amber biota in northern Myanmar". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 558: 109960. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2020.109960.

- ^ Yu, T.; Kelly, R.; Mu, L; Ross, A.; Kennedy, J.; Broly, P.; Xia, F.; Zhang, H.; Wang, B.; Dilcher, D. (2019-06-04). "An ammonite trapped in Burmese amber". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (23): 11345–11350. doi:10.1073/pnas.1821292116. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6561253. PMID 31085633.

- ^ Mao, Y.; Liang, K.; Su, Y.; Li, J.; Rao, X.; Zhang, H.; Xia, F.; Fu, Y.; Cai, C.; Huang, D. (2018-12-28). "Various amberground marine animals on Burmese amber with discussions on its age". Palaeoentomology. 1 (1): 91. doi:10.11646/palaeoentomology.1.1.11. ISSN 2624-2834.

- ^ Smith, Ru D. A.; Ross, Andrew J. (January 2018). "Amberground pholadid bivalve borings and inclusions in Burmese amber: implications for proximity of resin-producing forests to brackish waters, and the age of the amber". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 107 (2–3): 239–247. doi:10.1017/S1755691017000287. ISSN 1755-6910. S2CID 204250232.

- ^ Bolotov, Ivan N.; Aksenova, Olga V.; Vikhrev, Ilya V.; Konopleva, Ekaterina S.; Chapurina, Yulia E.; Kondakov, Alexander V. (2021-03-23). "A new fossil piddock (Bivalvia: Pholadidae) may indicate estuarine to freshwater environments near Cretaceous amber-producing forests in Myanmar". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 6646. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-86241-y. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 7988128. PMID 33758318.

- ^ Poinar, G.; Lambert, J.B.; Wu, Y. (2007-08-10). "Araucarian source of fossiliferous Burmese amber: Spectroscopic and anatomical evidence". Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas. 1: 449–455.

- ^ Dutta, S.; Mallick, M.; Kumar, K.; Mann, U.; Greenwood, P. F. (January 2011). "Terpenoid composition and botanical affinity of Cretaceous resins from India and Myanmar". International Journal of Coal Geology. 85 (1): 49–55. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2010.09.006.

- ^ Ross, A.J. 2018. Burmese (Myanmar) amber taxa, on-line checklist v.2018.2 104pp

- ^ Ross, A.J. 2019b. Burmese (Myanmar) amber taxa, on-line supplement v.2019.2. 33pp.

- ^ Engel, Michael S.; Breitkreuz, Laura C. V.; Cai, Chenyang; Alvarado, Mabel; Azar, Dany; Huang, Diying (15 February 2016). "The first Mesozoic microwhip scorpion (Palpigradi): a new genus and species in mid-Cretaceous amber from Myanmar". The Science of Nature. 103 (3–4): 19. Bibcode:2016SciNa.103...19E. doi:10.1007/s00114-016-1345-4. PMID 26879963. S2CID 14816297.

- ^ Müller, Sandro P.; Dunlop, Jason A.; Kotthoff, Ulrich; Hammel, Jörg U.; Harms, Danilo (February 2020). "The oldest short-tailed whipscorpion (Schizomida): A new genus and species from the Upper Cretaceous amber of northern Myanmar". Cretaceous Research. 106: 104227. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2019.104227.

- ^ Oliveira, I.; Bai, M.; Jahn, H.; Gross, V.; Martin, C.; Hammel, J. U.; Zhang, W.; Mayer, G. (2016). "Earliest Onychophoran in Amber Reveals Gondwanan Migration Patterns". Current Biology. 26 (19): 2594–2601. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.07.023. PMID 27693140.

- ^ W. W. Zhang and S. Q. Ge. 2017. Systematic paleontology, in A new species of Chresmodidae from Mid-Cretaceous amber discovered in Myanmar. Zoological Systematics 42:243-247

- ^ Lucena, D. A. A.; Melo, G. A. R. (2018). "Chrysidid wasps (Hymenoptera: Chrysididae) from Cretaceous Burmese amber: Phylogenetic affinities and classification". Cretaceous Research. 89: 279–291. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2018.03.018.

- ^ Grimaldi, D. A.; Vea, I. M. (2021). "Insects with 100 million-year-old dinosaur feathers are not ectoparasites". Nature Communications. 12 (1): Article number 1469. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-21751-x. PMC 7935990. PMID 33674573.

- ^ Weiwei Zhang, Mingxia Guo; Weiwei Zhang, Mingxia Guo. "A new species of ice crawlers from Burmese amber (Insecta: Grylloblattodea)". Zoological Systematics. 41 (3): 327–331. doi:10.11865/zs.201637. ISSN 2095-6827. S2CID 134290216.

- ^ Yu, Tingting; Wang, Bo; Pan, Huazhang (October 2018). "New terrestrial gastropods from mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber". Cretaceous Research. 90: 254–258. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2018.04.015.

- ^ Hirano, Takahiro; Asato, Kaito; Yamamoto, Shûhei; Takahashi, Yui; Chiba, Satoshi (December 2019). "Cretaceous amber fossils highlight the evolutionary history and morphological conservatism of land snails". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 15886. Bibcode:2019NatSR...915886H. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-51840-3. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6828811. PMID 31685840.

- ^ Bullis, David A.; Herhold, Hollister W.; Czekanski-Moir, Jesse E.; Grimaldi, David A.; Rundell, Rebecca J. (March 2020). "Diverse new tropical land snail species from mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Cyclophoroidea, Assimineidae)". Cretaceous Research. 107: 104267. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2019.104267.

- ^ Xing, Lida; McKellar, Ryan C.; Xu, Xing; Li, Gang; Bai, Ming; Persons, W. Scott; Miyashita, Tetsuto; Benton, Michael J.; Zhang, Jianping; Wolfe, Alexander P.; Yi, Qiru (December 2016). "A Feathered Dinosaur Tail with Primitive Plumage Trapped in Mid-Cretaceous Amber". Current Biology. 26 (24): 3352–3360. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.10.008. PMID 27939315.

- ^ Xing, Lida; O'Connor, Jingmai K.; McKellar, Ryan C.; Chiappe, Luis M.; Tseng, Kuowei; Li, Gang; Bai, Ming (September 2017). "A mid-Cretaceous enantiornithine (Aves) hatchling preserved in Burmese amber with unusual plumage". Gondwana Research. 49: 264–277. Bibcode:2017GondR..49..264X. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2017.06.001.

- ^ Xing, Lida; O'Connor, Jingmai K.; McKellar, Ryan C.; Chiappe, Luis M.; Bai, Ming; Tseng, Kuowei; Zhang, Jie; Yang, Haidong; Fang, Jun; Li, Gang (February 2018). "A flattened enantiornithine in mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber: morphology and preservation". Science Bulletin. 63 (4): 235–243. doi:10.1016/j.scib.2018.01.019.

- ^ Xing, Lida; McKellar, Ryan C.; O’Connor, Jingmai K.; Bai, Ming; Tseng, Kuowei; Chiappe, Luis M. (2019-01-30). "A fully feathered enantiornithine foot and wing fragment preserved in mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 927. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9..927X. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-37427-4. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6353931. PMID 30700773.

- ^ Xing, Lida; McKellar, Ryan C.; O’Connor, Jingmai K.; Niu, Kecheng; Mai, Huijuan (2019-10-29). "A mid-Cretaceous enantiornithine foot and tail feather preserved in Burmese amber". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 15513. Bibcode:2019NatSR...915513X. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-51929-9. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6820775. PMID 31664115.

- ^ Xing, Lida; McKellar, Ryan C.; O'Connor, Jingmai K. (February 2020). "An unusually large bird wing in mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber". Cretaceous Research. 110: 104412. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104412.

- ^ Xing, Lida; McKellar, Ryan C.; Wang, Min; Bai, Ming; O’Connor, Jingmai K.; Benton, Michael J.; Zhang, Jianping; Wang, Yan; Tseng, Kuowei; Lockley, Martin G.; Li, Gang (2016-06-28). "Mummified precocial bird wings in mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber". Nature Communications. 7 (1): 12089. Bibcode:2016NatCo...712089X. doi:10.1038/ncomms12089. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4931330. PMID 27352215.

- ^ Xing, Lida; O’Connor, Jingmai K.; Chiappe, Luis M.; McKellar, Ryan C.; Carroll, Nathan; Hu, Han; Bai, Ming; Lei, Fumin (2019). "A New Enantiornithine Bird with Unusual Pedal Proportions Found in Amber". Current Biology. 29 (14): 2396–2401. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.05.077. PMID 31303484.

- ^ Xing, Lida; O’Connor, Jingmai K.; Schmitz, Lars; Chiappe, Luis M.; McKellar, Ryan C.; Yi, Qiru; Li, Gang (March 2020). "Hummingbird-sized dinosaur from the Cretaceous period of Myanmar". Nature. 579 (7798): 245–249. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2068-4. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 32161388. S2CID 212670113.

- ^ Xing, Lida; Stanley, Edward L.; Bai, Ming; Blackburn, David C. (December 2018). "The earliest direct evidence of frogs in wet tropical forests from Cretaceous Burmese amber". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 8770. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8.8770X. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-26848-w. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6002357. PMID 29904068.

- ^ Xing, Lida; Caldwell, Michael W.; Chen, Rui; Nydam, Randall L.; Palci, Alessandro; Simões, Tiago R.; McKellar, Ryan C.; Lee, Michael S. Y.; Liu, Ye; Shi, Hongliang; Wang, Kuan (July 2018). "A mid-Cretaceous embryonic-to-neonate snake in amber from Myanmar". Science Advances. 4 (7): eaat5042. Bibcode:2018SciA....4.5042X. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aat5042. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 6051735. PMID 30035227.

- ^ Daza, Juan D.; Stanley, Edward L.; Wagner, Philipp; Bauer, Aaron M.; Grimaldi, David A. (March 2016). "Mid-Cretaceous amber fossils illuminate the past diversity of tropical lizards". Science Advances. 2 (3): e1501080. Bibcode:2016SciA....2E1080D. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1501080. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 4783129. PMID 26973870.

- ^ Arnold, E. Nicholas; Poinar, George (2008-08-11). "A 100 million year old gecko with sophisticated adhesive toe pads, preserved in amber from Myanmar". Zootaxa. 1847 (1): 62. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.1847.1.5. ISSN 1175-5334.

- ^ Daza, J. D.; Bauer, A. M.; Stanley, E. L.; Bolet, A.; Dickson, B.; Losos, J. B. (2018-11-01). "An Enigmatic Miniaturized and Attenuate Whole Lizard from the Mid-Cretaceous Amber of Myanmar" (PDF). Breviora. 563 (1): 1. doi:10.3099/mcz49.1. ISSN 0006-9698. S2CID 91589111.

- ^ Matsumoto, Ryoko; Evans, Susan E. (2018-01-03). Smith, Thierry (ed.). "The first record of albanerpetontid amphibians (Amphibia: Albanerpetontidae) from East Asia". PLOS ONE. 13 (1): e0189767. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1389767M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0189767. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5752013. PMID 29298317.

- ^ Daza, Juan D.; Stanley, Edward L.; Bolet, Arnau; Bauer, Aaron M.; Arias, J. Salvador; Čerňanský, Andrej; Bevitt, Joseph J.; Wagner, Philipp; Evans, Susan E. (2020-11-06). "Enigmatic amphibians in mid-Cretaceous amber were chameleon-like ballistic feeders". Science. 370 (6517): 687–691. doi:10.1126/science.abb6005. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 33154135. S2CID 226254862.

- ^ Rikkinen, Jouko; Grimaldi, David A.; Schmidt, Alexander R. (December 2019). "Morphological stasis in the first myxomycete from the Mesozoic, and the likely role of cryptobiosis". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 19730. Bibcode:2019NatSR...919730R. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-55622-9. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6930221. PMID 31874965.

- ^ Poinar, George; Vega, Fernando E. (2019-08-23). "Mid-Cretaceous cellular slime mold (Eukarya: Dictyostelia?) in Burmese amber". Historical Biology. 33 (5): 712–715. doi:10.1080/08912963.2019.1658095. ISSN 0891-2963. S2CID 202029760.

- ^ Chen, Dian; Zeng, Qingshuo; Yuan, Ye; Cui, Benxin; Luo, Wugan (November 2019). "Baltic amber or Burmese amber: FTIR studies on amber artifacts of Eastern Han Dynasty unearthed from Nanyang". Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 222: 117270. doi:10.1016/j.saa.2019.117270. PMID 31226615.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Zherikhin, V.V., Ross, A.J., 2000. A review of the history, geology and age of Burmese amber (Burmite). Bulletin of the Natural History Museum, London (Geology) 56 (1), 3–10.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pemberton, R. B. (1837). "Abstract of the Journal of a route travelled by Cap. Hannay from the Capital of Ava to the Amber Mines of the Hukong valley in the South east frontier of Assam". Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. 64: 248–278.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ross, A.; Mellish, C.; York, P.; Craighton, B. (2010). "Chapter 12: Burmese amber". In Penney, D. (ed.). Biodiversity of Fossils in Amber from the Major World Deposits. Siri Scientific Press. pp. 116–136. ISBN 978-0-9558636-4-6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Peretti, Adolf (December 2021). "An alternative perspective for acquisitions of amber from Myanmar including recommendations of the United Nations Human Rights Council". Journal of International Humanitarian Action. 6 (1): 12. doi:10.1186/s41018-021-00101-y. ISSN 2364-3412. S2CID 235174183.

- ^ Rippa, Alessandro; Yang, Yi (July 2017). "The Amber Road: Cross-Border Trade and the Regulation of the Burmite Market in Tengchong, Yunnan". TRaNS: Trans -Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia. 5 (2): 243–267. doi:10.1017/trn.2017.7. ISSN 2051-364X.

- ^ Lawton, Graham. "Blood amber: The exquisite trove of fossils fuelling war in Myanmar". New Scientist. Retrieved 2020-02-04.

- ^ Gammon, Katharine. "The Human Cost of Amber". The Atlantic. ISSN 1072-7825. Retrieved 2020-02-04.

- ^ Lawton, Graham. "Military now controls Myanmar's scientifically important amber mines". New Scientist. Retrieved 2020-02-04.

- ^ Joel, Lucas (2020-03-11). "Some Paleontologists Seek Halt to Myanmar Amber Fossil Research". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-03-13.

- ^ Rayfield, Emily J.; Theodor, Jessica M.; Polly, P. David (2020). Fossils from conflict zones and reproducibility of fossil-based scientific data. Society for Vertebrate Paleontology. pp. 1–2.

- ^ "News - Acta Palaeontologica Polonica". www.app.pan.pl. Retrieved 2020-05-19.

- ^ Barrett, Paul M.; Johanson, Zerina (2020-05-13). "Editorial: Myanmar (Burmese) Amber Statement". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology: 1. doi:10.1080/14772019.2020.1764313. ISSN 1477-2019.

- ^ Szwedo, Jacek; Wang, Bo; Soszyńska-Maj, Agnieszka; Azar, Dany; Ross, Andrew J. (2020-06-30). "International Palaeoentomological Society Statement". Palaeoentomology. 3 (3): 221–222. doi:10.11646/palaeoentomology.3.3.1. ISSN 2624-2834.

- ^ Haug, Joachim T.; Azar, Dany; et al. (September 2020). "Comment on the letter of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (SVP) dated April 21, 2020 regarding "Fossils from conflict zones and reproducibility of fossil-based scientific data": Myanmar amber". PalZ. 94 (3): 431–437. doi:10.1007/s12542-020-00524-9. ISSN 0031-0220.

- ^ Poinar, George; Ellenberger, Sieghard (April 2020). "Burmese Amber Fossils, Mining, Sales and Profits". Geoconservation Research. 3 (1). doi:10.30486/gcr.2020.1900981.1018.

- ^ Zherikhin, V. V.; Ross, A. J. (2000). "A review of the history, geology and age of Burmese amber burmite". Bulletin of the Natural History Museum, Geology Series.

- ^ Zheng, D.; Chang, S.-C.; Perrichot, V.; Dutta, S.; Rudra, A.; Mu, L.; Kelly, R. S.; Li, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Wong, J. (December 2018). "A Late Cretaceous amber biota from central Myanmar". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 3170. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.3170Z. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-05650-2. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6085374. PMID 30093646.

External links[]

- Burmese amber

- Paleontological sites of Asia

- Paleontology in Myanmar