Carmel, Indiana

Carmel, Indiana | |

|---|---|

City | |

Carmel City Hall | |

Seal | |

| Motto(s): "A Partnership for Tomorrow" | |

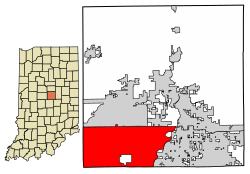

Location of Carmel in Hamilton County, Indiana | |

| Coordinates: 39°58′N 86°6′W / 39.967°N 86.100°WCoordinates: 39°58′N 86°6′W / 39.967°N 86.100°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Hamilton |

| Township | Clay |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | James Brainard (R) (1996-present) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 50.17 sq mi (129.94 km2) |

| • Land | 49.09 sq mi (127.13 km2) |

| • Water | 1.08 sq mi (2.80 km2) |

| Elevation | 853 ft (260 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 79,191 |

| • Estimate (2019)[3] | 101,068 |

| • Density | 2,059.00/sq mi (794.98/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 46032, 46033, 46074, 46082, 46280, 46290[4] |

| Area code(s) | 317, 463 |

| FIPS code | 18-10342 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0432143[5] |

| Interstate Highways | |

| U.S. Highways | |

| Website | www |

Carmel /ˈkɑːrməl/ is a suburban city in Indiana immediately north of Indianapolis. With a population of 101,068,[6] the city spans 47 square miles (120 km2) across Clay Township in Hamilton County, Indiana, and is bordered by the White River to the east; the Hamilton-Boone county line to the west; 96th Street to the south and 146th Street to the north. Though Carmel was home to one of the first electronic automated traffic signals in the state,[7] the city has constructed some 128 roundabouts since 1998, earning its moniker as the "Roundabout Capital of the U.S."[8]

History[]

Carmel was originally called "Bethlehem". It was platted and recorded in 1837 by Daniel Warren, Alexander Mills, John Phelps, and Seth Green.[9]:241 The original settlers were predominantly Quakers.[10] Today, the plot first established in Bethlehem, located at the intersection of Rangeline Road and Main Street, is marked by a clock tower, donated by the local Rotary Club in 2002. A post office was established as "Carmel" in 1846 because Indiana already had a post office called Bethlehem.[11] The town of Bethlehem was renamed "Carmel" in 1874, due to the need of a post office, at which time it was incorporated.[9]:247

In 1924, one of the first automatic traffic signals in the U.S. was installed at the intersection of Main Street and Rangeline Road. The signal was the invention of Leslie Haines and is currently in the old train station on the Monon Trail.[12]

The Carmel Monon Depot, John Kinzer House, and Thornhurst Addition are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[13][14]

Geography[]

Carmel occupies the southwestern part of Hamilton County, adjacent to Indianapolis and, with the annexation of Home Place in 2018, is now entirely coextensive with Clay Township. It is bordered to the north by Westfield, to the northeast by Noblesville, to the east by Fishers, to the south by Indianapolis in Marion County, and to the west by Zionsville in Boone County. The center of Carmel is 15 miles (24 km) north of the center of Indianapolis.

According to the 2010 census, Carmel has a total area of 48.545 square miles (125.73 km2), of which 47.46 square miles (122.92 km2) (or 97.76%) is land and 1.085 square miles (2.81 km2) (or 2.24%) is water.[15]

Major east–west streets in Carmel generally end in a 6 and include 96th Street (the southern border), 106th, 116th, 126th, 131st, 136th, and 146th (which marks the northern border). The numbering system is aligned to that of Marion and Hamilton counties. Main Street (131st) runs east–west through Carmel's Art & Design District; Carmel Drive runs generally east–west through the main shopping area, and City Center Drive runs east–west near Carmel's City Center project.

North–south streets are not numbered and include (west to east) Michigan, Shelborne, Towne, Ditch, Spring Mill, Meridian, Guilford, Rangeline, Keystone, Carey, Gray, Hazel Dell, and River. Some of these roads are continuations of corresponding streets in Indianapolis. Towne Road replaces the name Township Line Road at 96th Street, while Westfield Boulevard becomes Rangeline north of 116th Street. Meridian Street (US 31) and Keystone Parkway (formerly Keystone Avenue/SR 431) are the major thoroughfares, extending from 96th Street in the south and merging just south of 146th Street. The City of Carmel is nationally noted for having over 100 roundabouts within its borders, with even more presently under construction or planned.[16][17][18]

Demographics[]

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 92 | — | |

| 1890 | 471 | 412.0% | |

| 1900 | 498 | 5.7% | |

| 1910 | 626 | 25.7% | |

| 1920 | 598 | −4.5% | |

| 1930 | 682 | 14.0% | |

| 1940 | 771 | 13.0% | |

| 1950 | 1,009 | 30.9% | |

| 1960 | 1,442 | 42.9% | |

| 1970 | 6,691 | 364.0% | |

| 1980 | 18,272 | 173.1% | |

| 1990 | 25,380 | 38.9% | |

| 2000 | 37,733 | 48.7% | |

| 2010 | 79,191 | 109.9% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 101,068 | [3] | 27.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[19] 2018 Estimate[20] | |||

According to a 2017 estimate, the median household income in the city was $109,201.

The median home price between 2013 and 2017 was $320,400.[6]

2010 census[]

As of the census[2] of 2010, there were 79,191 people, 28,997 households, and 21,855 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,668.6 inhabitants per square mile (644.3/km2). There were 30,738 housing units at an average density of 647.7 per square mile (250.1/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 85.4% White, 3.0% African American, 0.2% Native American, 8.9% Asian, 0.7% from other races, and 1.8% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 2.5% of the population.

There were 28,997 households, of which 41.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 66.6% were married couples living together, 6.3% had a female householder with no partner present, 2.4% had a male householder with no partner present, and 24.6% were non-families. 20.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 6.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.71 and the average family size was 3.18.

The median age in the city was 39.2 years. 29.4% of residents were under the age of 18; 5.3% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 25.2% were from 25 to 44; 29.7% were from 45 to 64; and 10.4% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.7% male and 51.3% female.

Economy[]

The Meridian Corridor serves as a large concentration of corporate office space within the city. It is home to more than 40 corporate headquarters and many more regional offices. Several large companies reside in Carmel, and it serves as the national headquarters for Allegion, CNO Financial Group, MISO, and Delta Faucet.

Top employers[]

As of January 2017, the city's 10 largest employers were:[21]

| # | Employer | # of employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | CNO Financial Group | 1,600 |

| 2 | Geico | 1,250 |

| 3 | RCI, LLC | 1,125 |

| 4 | Capital Group Companies | 975 |

| 5 | Liberty Mutual | 900 |

| 6 | KAR Auction Services (Adesa) | 892 |

| 7 | IU Health North | 800 |

| 8 | Midcontinent ISO | 700 |

| 9 | NextGear Capital | 694 |

| 10 | Allegion | 595 |

Arts and culture[]

Rollfast Gran Fondo[]

Indiana's only Gran Fondo, this cycling event attracts professional cyclists as well as recreational riders. In 2019, the event is the World Championship for the Gran Fondo World Tour. Each route is fully supported with food, drinks, and mechanical support.[22]

Carmel Farmers Market[]

Founded in 1998, the Carmel Farmers Market is one of the largest in the state of Indiana, with over 60 vendors of Indiana-grown and/or produced edible products. The market, which is managed by an all-volunteer committee, is held each Saturday morning from mid-May through the first weekend of October on Center Green at the Palladium, the farmers market attracts over 60,000 people a year.[23]

Carmel Monon Community Center[]

A $24.5 million water park and fitness center is the centerpiece of Carmel's $55 million Central Park, which opened in 2007.[citation needed] The Outdoor Water Park consists of two water slides, a drop slide, a rock-climbing wall, a lazy river, a kiddie pool, a large zero depth activity pool, Flowrider, and a lap pool. The fitness center consists of an indoor lap pool, a recreation pool with its own set of water slides and a snack bar, gymnasium, 1⁄8-mile (0.20 km) indoor running track, and the Kids Zone childcare. The building housing the Carmel Clay Parks Department offices is connected by an elevated walkway over the Monon Trail.[citation needed]

Monon Trail[]

The Monon Greenway is a multi-use trail that is part of the Rails-to-Trails movement. It runs from 10th Street near downtown Indianapolis through Broad Ripple and then crosses into Carmel at 96th Street and continues north through 146th Street into Westfield and continues to Sheridan. The trail ends in Sheridan near the intersection of Opel and 236th streets. In January 2006, speed limit signs of 15 to 20 miles per hour (24 to 32 km/h) were added to sections of the trail in Hamilton County.

Carmel Arts & Design District[]

Designed to promote small businesses and local artisans, Carmel's Arts and Design District and City Center is in Old Town Carmel and flanked by Carmel High School on the east and the Monon Greenway on the west, with the state goal of celebrating the creativity and craftsmanship of the miniature art form.. The district includes the Carmel Clay Public Library,[24] the Hamilton County Convention & Visitor's Bureau and Welcome Center, and a collection of art galleries, boutiques, interior designers, cafes, and restaurants. Lifelike sculptures by John Seward Johnson II ornament the streets of the district.

The district hosts several annual events and festivals. The Carmel Artomobilia Collector Car Show showcases classic, vintage, exotic and rare cars, along with art inspired by automobile design.[25] Every September, the Carmel International Arts Festival features a juried art exhibit of artists from around the world,[26] concerts, dance performances, and hands-on activities for children.

In the heart of the district stands the Museum of Miniature Houses, open since 1993. The museum has seven exhibit rooms of fully furnished houses, room displays, and collections of miniature glassware, clocks, tools, and dolls.

Carmel City Center[]

Carmel City Center is a one-million-square-foot (93,000 m2), $300 million, mixed-use development located in the heart of Carmel.[27] Carmel City Center is home to The Palladium at the Center for the Performing Arts, which includes a 1,600-seat concert hall, 500-seat theater, and 200-seat black box theater. This pedestrian-based master plan development is located at the southwest corner of City Center Drive (126th Street) and Range Line Road. The Monon Greenway runs directly through the project. Carmel City Center was developed as a public/private partnership.

Shopping[]

Clay Terrace is one of the largest retail centers in Carmel. Other shopping areas include Carmel City Center,[28] Mohawk Trails Plaza, and Merchants' Square. The Carmel Arts & Design District has a number of retail establishments along Main Street, Range Line Road, 3rd Avenue, and 2nd Street.[29]

Kawachinagano Japanese Garden[]

Ground was broken for the Japanese Garden south of City Hall in 2007. The garden was dedicated in 2009 as the 15th anniversary of Carmel's Sister City relationship with Kawachinagano, Japan, was celebrated.[30] An Azumaya-style tea gazebo was constructed in 2011 and dedicated on May 2 of that year.[31]

Great American Songbook Foundation[]

The Great American Songbook Foundation is the nation's only foundation and museum dedicated to preserving the music of the early to mid 1900s. The foundation is led by Michael Feinstein, who is also the artistic director of the Center for the Performing Arts.[32][33]

Government[]

The government consists of a mayor and a city council. The current mayor is James Brainard.[34] The city council consists of nine members. Six are elected from individual districts and three are elected at-large.

Planned development[]

In mid-2017, the city council was considering a multimillion-dollar bond issue that would cover the cost of roundabouts, paths, roadwork, land acquisition by the Carmel Redevelopment Commission and would include the purchase of an antique carousel.[35] from a Canadian amusement park for an estimated purchase price of CAD $3 million, approximately US$2.25 million.[36] However, a citizen led petition drive against the purchase caused the city counsel to remove it from the bond issue.[37]

According to the Indiana Department of Local Government Finance, as of 2019 the City of Carmel had an overall debt load of $1.3 billion.[38]

List of mayors[]

| № | Portrait | Mayor | Term of office[39] | Election | Party[40][41] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Albert Pickett | January 1, 1976 – January 1, 1980 |

1975 | Republican | ||

| 2 | Jane A. Reiman | January 1, 1980 – January 1, 1988 |

1979 | Republican | ||

| 1983 | ||||||

| 3 | Dorothy J. Hancock | January 1, 1988 – January 1, 1992 |

1987 | Republican | ||

| 4 | Ted Johnson | January 1, 1992 – January 1, 1996 |

1991 | Republican | ||

| 5 |

|

James Brainard | January 1, 1996 – Incumbent |

1995 | Republican | |

| 1999 | ||||||

| 2003 | ||||||

| 2007 | ||||||

| 2011 | ||||||

| 2015 | ||||||

| 2019 | ||||||

Education[]

Public schools[]

The Carmel Clay Schools district has 11 elementary schools, three middle schools, and one high school. Student enrollment for the district is above 14,500.[42]

The elementary schools are Carmel Elementary,[43] Cherry Tree Elementary,[44] College Wood Elementary,[45] Forest Dale Elementary, Mohawk Trails Elementary, Orchard Park Elementary, Prairie Trace Elementary, Smoky Row Elementary, Towne Meadow Elementary, West Clay Elementary, and Woodbrook Elementary.

The three middle schools are Carmel Middle School,[46] Clay Middle School, and Creekside Middle School. They feed into Carmel High School.[47]

Independent schools[]

Carmel has several private schools, including Pilgrim Lutheran Preschool (12 mo. - 6 years), St. Elizabeth Seton Preschool (2 years-K), Midwest Academy (4-12), Our Lady of Mount Carmel Catholic School (K-8), Walnut Grove Christian School (K-8), and University High School.[48]

Notable people[]

- Bernie Allen, baseball player.[49]

- Ted Allen, television personality

- Franklin Booth, influential pen-and-ink artist

- Steve Chassey, Indy Car driver

- Pete Dye, golf course designer

- Jay Howard, British racing driver[50]

- Steve Inskeep, host of Morning Edition, National Public Radio

- Jake Lloyd, former actor known for his portrayal of young Anakin Skywalker in Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace

- Josh McRoberts, former professional basketball player for the Dallas Mavericks

- Dorothy Letterman Mengering, mother of comedian and talk show host David Letterman

- Rajeev Ram, American professional tennis player, the winner of 2019 Australian Open – Mixed Doubles tournament.[51]

- Lee Schmidt, golf course designer

- Rob Schmitt, reporter and Fox News co-host

- Avriel Shull, architectural designer/builder and interior decorator

- Zach Trotman, professional hockey player, currently playing for the Pittsburgh Penguins

- Sheldon Vanauken, American author known for A Severe Mercy (1977).

- Seema Verma, American health policy consultant and former Administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- Adam Vinatieri, professional football placekicker for the Indianapolis Colts

- Todd Young, currently the senior United States Senator from Indiana

Sister cities[]

Carmel has two sister cities as designated by Sister Cities International.[52]

Kawachinagano, Osaka Prefecture, Japan (1994)

Kawachinagano, Osaka Prefecture, Japan (1994) Xiangyang, Hubei, China (2012)

Xiangyang, Hubei, China (2012)

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-12-11.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ "ZIP Code by City and State - Carmel, IN". United States Postal Service. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Quick Facts - Carmel city, Indiana". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- ^ Contreras, Natalia (January 1, 2019). "Carmel loves roundabouts: Here's why". The Indianapolis Star. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ Tuohy, John (December 1, 2019). "Carmel roundabouts increased crashes at many major intersections". The Indianapolis Star. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Haines, John F. (1915). History of Hamilton County, Indiana: Her People, Industries and Institutions, Volume 1. B.F. Bowen & Co.

- ^ "Hamilton County History Timeline". Carmel Clay Historical Society. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ "Hamilton County". Jim Forte Postal History. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ^ "History of Carmel, Indiana". City of Carmel, Indiana. Archived from the original on 2007-06-15. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Listings". Weekly List of Actions Taken on Properties: 6/24/13 through 6/28/13. National Park Service. 2013-07-05.

- ^ "G001 - Geographic Identifiers - 2010 Census Summary File 1". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2020-02-13. Retrieved 2015-07-28.

- ^ Sims, Chris. "Carmel's latest reason to celebrate: Roundabout No. 110". The Indianapolis Star.

- ^ "Public Roads -Roundabouts Coming Full Circle, Autumn 2017-FHWA-HRT-18-001". www.fhwa.dot.gov.

- ^ "Roundabout Index: Carmel, IN". All About Roundabouts Society. 23 November 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- ^ "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "TOP EMPLOYERS". Invest Hamilton County. Archived from the original on 2017-10-24. Retrieved 2017-10-23.

- ^ "Home". Rollfast.

- ^ "Carmel Farmers Market - LocalHarvest". www.localharvest.org.

- ^ "Library Name". haplr-index.com. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ "Home". ARTOMOBILIA. Retrieved 2017-05-03.

- ^ "Tickets & Events". The Center For The Performing Arts.

- ^ "Carmel City Center FAQ" (PDF). carmelcitycenter.com. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ Parallelus. "Carmel City Center | Official Site of Downtown Carmel". Retrieved 2019-01-28.

- ^ "Carmel Arts and Design District : Carmel, Indiana". www.carmelartsanddesign.com. Retrieved 2019-01-28.

- ^ "City of Carmel, IN: History". City of Carmel, IN. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ Heck, Nancy S. "Dedication of Japanese Tea Gazebo with Sister City Kawachinagano, Japan". Indy Biz. Archived from the original on 22 April 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ "The Center for the Performing Arts | Great American Songbook Foundation". The Center For The Performing Arts. Retrieved 2019-01-28.

- ^ "The Center for the Performing Arts | About". The Center For The Performing Arts. Retrieved 2019-01-28.

- ^ "City of Carmel, IN : Mayor". in.gov. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ "Carmel considers $101M for roundabouts, land, paths, carousel". Chris Sikich. IndyStar. 10 July 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ^ "Toronto's 110-year old carousel on Centre Island sold for $3 million". Fatima Syed. Toronto Star. 19 July 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ^ McKinney, Matt (September 19, 2017). "Carmel's controversial $5M carousel plan removed". WRTV. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ "Carmel Mayor Jim Brainard sees $1.3B as worthy investment. His challenger sees troublesome debt". Natalia Contreras. 2 May 2019. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- ^ "History - City of Carmel". www.carmel.in.gov.

- ^ "Republicans Sweep Carmel's 1st City Vote". The Indianapolis Star. November 5, 1975. p. 12. Retrieved April 11, 2019.

- ^ "Carmel Grows Up: The History and Vision of an Edge City" (PDF). www.carmelclayhistory.org. 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2019.

- ^ "Carmel Clay Schools". ccs.k12.in.us. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ "Carmel Elementary School". 1.ccs.k12.in.us. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ "Cherry Tree Elementary". myccs.ccs.k12.in.us. Archived from the original on 2017-10-07. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ "College Wood Elementary". myccs.ccs.k12.in.us. Archived from the original on 2017-10-07. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ "Carmel Middle School". www1.ccs.k12.in.us.

- ^ "Carmel High School". carmelhighschool.net. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ "K-12 Schools in Carmel, IN". Niche.

- ^ Bernie Allen bio at Society for American Baseball Research

- ^ Morrison, Janelle (May 2021). "Carmel's Own IndyCar Driver Jay Howard: On Developing the Next Generation of Drivers". Carmel Monthly magazine.

- ^ Brown, Brad (31 January 2019). "Carmel's Rajeev Ram wins major mixed doubles title". RTV6. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- ^ "Interactive City Directory - Carmel, Indiana". SisterCities International. Archived from the original on 2017-04-22. Retrieved April 21, 2017.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carmel. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Carmel (Indiana). |

- Carmel, Indiana

- Cities in Indiana

- Cities in Hamilton County, Indiana

- Indianapolis metropolitan area