Chaos game

In mathematics, the term chaos game originally referred to a method of creating a fractal, using a polygon and an initial point selected at random inside it.[1][2] The fractal is created by iteratively creating a sequence of points, starting with the initial random point, in which each point in the sequence is a given fraction of the distance between the previous point and one of the vertices of the polygon; the vertex is chosen at random in each iteration. Repeating this iterative process a large number of times, selecting the vertex at random on each iteration, and throwing out the first few points in the sequence, will often (but not always) produce a fractal shape. Using a regular triangle and the factor 1/2 will result in the Sierpinski triangle, while creating the proper arrangement with four points and a factor 1/2 will create a display of a "Sierpinski Tetrahedron", the three-dimensional analogue of the Sierpinski triangle. As the number of points is increased to a number N, the arrangement forms a corresponding (N-1)-dimensional Sierpinski Simplex.

The term has been generalized to refer to a method of generating the attractor, or the fixed point, of any iterated function system (IFS). Starting with any point x0, successive iterations are formed as xk+1 = fr(xk), where fr is a member of the given IFS randomly selected for each iteration. The iterations converge to the fixed point of the IFS. Whenever x0 belongs to the attractor of the IFS, all iterations xk stay inside the attractor and, with probability 1, form a dense set in the latter.

The "chaos game" method plots points in random order all over the attractor. This is in contrast to other methods of drawing fractals, which test each pixel on the screen to see whether it belongs to the fractal. The general shape of a fractal can be plotted quickly with the "chaos game" method, but it may be difficult to plot some areas of the fractal in detail.

The "chaos game" method is mentioned in Tom Stoppard's 1993 play Arcadia.[3]

With the aid of the "chaos game" a new fractal can be made and while making the new fractal some parameters can be obtained. These parameters are useful for applications of fractal theory such as classification and identification.[4][5] The new fractal is self-similar to the original in some important features such as fractal dimension.

If in the "chaos game" you start at each vertex and go through all possible paths that the game can take, you will get the same image as with only taking one random path. However, taking more than one path is rarely done since the overhead for keeping track of every path makes it far slower to calculate. This method does have the advantages of illustrating how the fractal is formed more clearly than the standard method as well as being deterministic.

Restricted chaos game[]

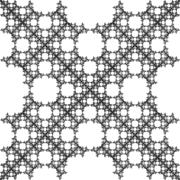

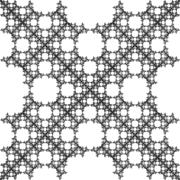

If the chaos game is run with a square, no fractal appears and the interior of the square fills evenly with points. However, if restrictions are placed on the choice of vertices, fractals will appear in the square. For example, if the current vertex cannot be chosen in the next iteration, this fractal appears:

If the current vertex cannot be one place away (anti-clockwise) from the previously chosen vertex, this fractal appears:

If the point is prevented from landing on a particular region of the square, the shape of that region will be reproduced as a fractal in other and apparently unrestricted parts of the square. Here, for example, is the fractal produced when the point cannot jump so as to land on a red Om symbol at the center of the square[further explanation needed]:

A point inside a square repeatedly jumps half of the distance towards a randomly chosen vertex, but the currently chosen vertex cannot be 2 places away from the previously chosen vertex.

A point inside a square repeatedly jumps half of the distance towards a randomly chosen vertex, but the currently chosen vertex cannot neighbor the previously chosen vertex if the two previously chosen vertices are the same.

A point inside a pentagon repeatedly jumps half of the distance towards a randomly chosen vertex, but the currently chosen vertex cannot be the same as the previously chosen vertex.

A point inside a pentagon repeatedly jumps half of the distance towards a randomly chosen vertex, but the currently chosen vertex cannot neighbor the previously chosen vertex if the two previously chosen vertices are the same.

Jumps other than 1/2[]

When the length of the jump towards a vertex or another point is not 1/2, the chaos game generates other fractals, some of them very well-known. For example, when the jump is 2/3 and the point can also jump towards the center of the square, the chaos game generates the Vicsek fractal:

When the jump is 2/3 and the point can also jump towards the midpoints of the four sides, the chaos game generates the Sierpinski carpet:

When the jump is 1/phi and the point is jumping at random towards one or another of the five vertices of a regular pentagon, the chaos game generates a pentagonal n-flake:

See also[]

External links[]

- Simulations of chaos games made with Scratch.

- Explanation of the chaos game at beltoforion.de.

References[]

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Chaos Game". MathWorld.

- ^ Barnsley, Michael (1993). Fractals Everywhere. Morgan Kaufmann. ISBN 978-0-12-079061-6.

- ^ Devaney, Robert L. "Chaos, Fractals, and Arcadia". Department of Mathematics, Boston University.

- ^ Jampour, Mahdi; Yaghoobi, Mahdi; Ashourzadeh, Maryam; Soleimani, Adel (1 September 2010). "A new fast technique for fingerprint identification with fractal and chaos game theory". Fractals. 18 (3): 293–300. doi:10.1142/s0218348x10005020. ISSN 0218-348X – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Jampour, Mahdi; Javidi, Mohammad M.; Soleymani, Adel; Ashourzadeh, Maryam; Yaghoobi, Mahdi (2010). "A New Technique in saving Fingerprint with low volume by using Chaos Game and Fractal Theory". . 1 (3): 27. doi:10.9781/ijimai.2010.135. ISSN 1989-1660.

- Fractals

- Chaos theory