Dutch diaspora

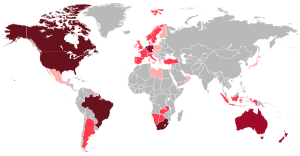

The Dutch diaspora consists of Dutch people and their descendants living outside the Netherlands.[1]

Emigration from the Netherlands has been occurring for at least four hundred years, and may be traced back to the international presence of the Dutch Empire and its monopoly on mercantile shipping in many parts of the world.[2] Dutch people settled permanently in a number of former Dutch colonies or trading enclaves abroad, namely the Dutch Caribbean, the Dutch Cape Colony, the Dutch East Indies, Surinam, and New Netherland.[2] Since the end of the Second World War, the largest proportion of Dutch emigrants have moved to Anglophone countries, namely Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States, mainly seeking better employment opportunities.[1] Postwar emigration from the Netherlands peaked between 1948 and 1963, with occasional spikes in the 1980s and the mid-2000s.[1] Cross-border migration to Belgium and Germany has become more common since 2001, driven by the rising cost of housing in major Dutch cities.[1]

Early emigration[]

The first big wave of Dutch immigrants to leave the Low Countries were from present day Northern Belgium as they wanted to escape the heavily urbanised cities in Western Flanders. They arrived in Brandenburg in 1157. Due to this, the area is known as "Fläming" (Fleming) in reference to the Duchy that these immigrants came from. Because of a number of devastating floods in the provinces of Zeeland and Holland in the 12th century, large numbers of farmers migrated to The Wash in England, the delta of the Gironde in France, around Bremen, Hamburg and western North Rhine-Westphalia.[3] Until the late 16th century, many Dutchmen and women (invited by the German margrave) moved to the delta of the Elbe, around Berlin, where they dried swamps, canalized rivers and built numerous dikes. Today, the Berlin dialect still bears some Dutch features.[4]

The town of Nymburk in the Kingdom of Bohemia was settled by Dutch colonists during the medieval eastward migration in the 13th century.[5]

Overseas emigration of the Dutch started around the 16th century, beginning a Dutch colonial empire. The first Dutch settlers arrived in the New World in 1614 and built a number of settlements around the mouth of the Hudson River, establishing the colony of New Netherland, with its capital at New Amsterdam (the future world metropolis of New York City). Dutch explorers also discovered Australia and New Zealand in 1606, though they did not settle the new lands; and Dutch immigration to these countries did not begin until after the Second World War. The Dutch were also one of the few Europeans to successfully settle Africa prior to the late 19th century.[6]

South Africa[]

The Cape of Good Hope was first settled by Europeans under the auspices of the Dutch East India Company (also known by its Dutch initials VOC), which established a victualing station there in 1652 to provide its outward bound fleets with fresh provisions and a harbour of refuge during the long sea journey from Europe to Asia.[7] Since the primary purpose of the Cape settlement at the time was to stock provisions for passing Dutch ships, the VOC offered grants of farmland to its employees under the condition they would cultivate grain for company warehouses, and released them from their contracts to save on their wages.[7] Prospective employees had to be married Dutch citizens, considered "of good character" by the company, and had to commit to spending at least twenty years on the African continent.[7] They were issued with a letter of freedom, known as a "vrijbrief", which released them from company service,[8] and received farms of thirteen and a half morgen each.[7] However, the new farmers were also subject to heavy restrictions: they were ordered to focus on cultivating grain, and each year their harvest was to be sold exclusively to Dutch officials at fixed prices.[9] They were forbidden from growing tobacco, producing vegetables for any purpose other than personal consumption, or purchasing cattle from the native tribes at rates which differed from those set by the company.[7] With time, these restrictions and other attempts by the colonial authorities to control the European population resulted in successive generations of settlers and their descendants becoming increasingly localised in their loyalties and national identity and hostile towards the colonial government.[10]

Relatively few Dutch women accompanied the first Dutch settlers to the Cape of Good Hope, and one natural consequence of the unbalanced gender ratio was that between 1652 and 1672 some 75% of children born to slaves in the colony had Dutch fathers.[11] The majority of slaves had been imported from the East Indies (Indonesia), India, Madagascar, and parts of eastern Africa.[12] This resulted in the formation of a new ethnic group, the Cape Coloureds, most of whom adopted the Dutch language and were instrumental in shaping it into a new regional dialect, Afrikaans.[11]

In 1691, there were at least 660 Dutch people living at the Cape of Good Hope.[13] This had increased to about 13,000 by the end of Dutch rule, or one half of the Cape's European population.[13][14] The remaining Europeans settled during the Dutch colonial era were Germans or French Huguenots, reflecting the multi-national nature of the VOC workforce and its settlements.[14] Thereafter the number of people of Dutch ancestry at the Cape became difficult to estimate, due in part to the almost universal adoption of the Dutch language and the Dutch Reformed Church by those of German or French origin, as well as a significant degree of intermarriage.[15] Since the late nineteenth century, the term Afrikaner has been evoked to describe white South Africans descended from the Cape's original Dutch-speaking settlers, regardless of ethnic heritage.[16]

The colony was captured by the British during the Napoleonic Wars, as the Dutch Republic was transformed by France into the Batavian Republic which subsequently declared war on Britain.[17] Following the end of the conflict, the Cape was formally ceded to Britain under the terms of the Treaty of Paris in 1815.[17]

Many of the Afrikaner community soon grew disillusioned with British rule, in particular the imposition of an Anglophone common law system and the abolition of slavery in the Cape, which was a major source of income for many Afrikaners.[18] One such Afrikaner was Christoffel Brand, son of a former senior VOC official, who became the first Speaker of the Parliament of the Cape of Good Hope.[18] Brand claimed that "England has taken from the old colonists of the Cape everything that was dear to them: their country, their laws, their customs, their slaves, their money, yes even their mother tongue...[the Afrikaners] had done everything to prove that they wanted to be British, while their conquerors had continually worked to remind them they were Hollanders."[18] In 1830, De Zuid-Afrikaan was founded as a Dutch-language newspaper by Brand to provide a mouthpiece for the Boer upper-class.[19] It was followed shortly afterwards by the establishment of a university where Dutch was the official language and several Afrikaner societies for the arts.[18] This was seen as the beginning of an Afrikaner ethnic consciousness: in 1835 one local Dutch-language newspaper noted the rise of a newfound sentiment that "a colonist of Dutch descent cannot become an Englishman, nor should he strive to be a Hollander".[20]

The most rural section of the Afrikaner community, known as Boers, undertook the Great Trek deep into South Africa's interior and founding their own autonomous Boer republics, the Transvaal Republic and the Orange Free State.[21] The Boer republics encouraged immigration from the Netherlands, as Dutch migrants were valued for their education and technical skills.[22]

Another wave of Dutch immigration to South Africa occurred in the wake of World War II, when many Dutch citizens were moving abroad to escape housing shortages and depressed economic opportunities at home.[1] South Africa registered a net gain of 45,000 Dutch immigrants between 1950 and 2001.[1]

Taiwan[]

The Dutch East India Company established the Dutch Formosa colony on Taiwan in 1624. During the Siege of Fort Zeelandia in 1662 in which Chinese Ming loyalist forces commanded by Koxinga besieged and defeated the Dutch East India Company and conquered Taiwan, the Chinese took Dutch women and children prisoner. The Dutch missionary Antonius Hambroek, two of his daughters, and his wife were among the Dutch prisoners of war with Koxinga. Koxinga sent Hambroek to Fort Zeelandia demanding he persuade them to surrender or else Hambroek would be killed when he returned. Hambroek returned to the Fort, where two of his other daughters were. He urged the Fort not to surrender, and returned to Koxinga's camp. He was then executed by decapitation, and in addition to this, a rumor was spreading among the Chinese that the Dutch were encouraging the native Taiwan aboriginals to kill Chinese, so Koxinga ordered the mass execution of Dutch male prisoners in retaliation, in addition to a few women and children also being killed. The surviving Dutch women and children were then turned into slaves. Koxinga took Hambroek's teenage daughter as a concubine,[23][24][25] and Dutch women were sold to Chinese soldiers to become their wives, the daily journal of the Dutch fort recorded that "the best were preserved for the use of the commanders, and then sold to the common soldiers. Happy was she that fell to the lot of an unmarried man, being thereby freed from vexations by the Chinese women, who are very jealous of their husbands."[26] In 1684 some of these Dutch wives were still captives of the Chinese.[27]

Some Dutch physical looks like auburn and red hair among people in regions of south Taiwan are a consequence of this episode of Dutch women becoming concubines to the Chinese commanders.[28] The Chinese took Dutch women as slave concubines and wives and they were never freed: in 1684 some were reported to be living, in Quemoy a Dutch merchant was contacted with an arrangement to release the prisoners which was proposed by a son of Koxinga's but it came to nothing.[29] The Chinese officers used the Dutch women they received as concubines.[30][31][32] The Dutch women were used for sexual pleasure by Koxinga's commanders.[33] This event of Dutch women being distributed to the Chinese soldiers and commanders was recorded in the daily journal of the fort.[34]

A teenage daughter of the Dutch missionary Anthonius Hambroek became a concubine to Koxinga, she was described by the Dutch commander Caeuw as "a very sweet and pleasing maiden".[35][36]

Dutch language accounts record this incident of Chinese taking Dutch women as concubines and the date of Hambroek's daughter.[37][38][39][40]

Vietnam[]

Much of the business conducted with foreign men in Southeast Asia was done by the local women, who served engaged in both sexual and mercantile intercourse with foreign male traders. A Portuguese and Malay speaking Vietnamese woman who lived in Macao for an extensive period of time was the person who interpreted for the first diplomatic meeting between Cochin-China and a Dutch delegation, she served as an interpreter for three decades in the Cochin-China court with an old woman who had been married to three husbands, one Vietnamese and two Portuguese.[41] Alexander Hamilton said that "The Tonquiners used to be very desirous of having a brood of Europeans in their country, for which reason the greatest nobles thought it no shame or disgrace to marry their daughters to English and Dutch seamen, for the time they were to stay in Tonquin, and often presented their sons-in-law pretty handsomely at their departure, especially if they left their wives with child; but adultery was dangerous to the husband, for they are well versed in the art of poisoning."[42]

United States[]

The first Dutchmen to come to the United States of America were explorers led by English captain Henry Hudson (in the service of the Dutch Republic) who arrived in 1609 and mapped what is now known as the Hudson River on the ship De Halve Maen (or the Half Moon in English). Their initial goal was to find an alternative route to Asia, but they found good farmland and plenty of wildlife instead.

The Dutch were one of the earliest Europeans who made their way to the New World. In 1614, the first Dutch settlers arrived and founded a number of villages and a town called New Amsterdam on the East Coast, which would become the future world metropolis of New York City. Nowadays, towns with prominent Dutch communities are located in the Midwest, particularly in the Chicago metropolitan area, Wisconsin, West Michigan, Iowa and some other northern states. Sioux Center, Iowa is the city with the largest percentage of Dutch in the United States (66% of the total population). Also, there are three private high schools with their respective primary school feeders in the Chicago area that mainly serve the Dutch-American community. These communities can be found in DuPage County, southwest Cook County and Northwest Indiana.

Canada[]

Dutch emigration to Canada peaked between 1951 and 1953, when an average of 20,000 people per year made the crossing. This exodus followed the harsh years in Europe as a result of the Second World War. One of the reasons many Dutch chose Canada as their new home was because of the excellent relations between the two countries, which specially blossomed because it was mainly Canadian troops who liberated the Netherlands in 1944-1945.[43]

Today almost 400,000 people of Dutch ancestry are registered as permanently living in Canada. About 130,000 Canadians were born in the Netherlands and there are another 600,000 Canadian citizens with at least one Dutch parent.[44]

According to Statistics Canada in 2016, some 1,111,645 Canadians identified their ethnic origin to be Dutch.[45]

Caribbean[]

Both the Leeward (Alonso de Ojeda, 1499) and Windward (Christopher Columbus, 1493) island groups were discovered and initially settled by the Spanish. In the 17th century, the islands were conquered by the Dutch West India Company after the defeat of Spain to the Netherlands in Eighty Years' War and were used as bases for the slave trade. Very few Dutch people settled the Caribbean; most were traders or (former) sailors. Today most Dutch people living in the Dutch Antilles are wealthy and recent arrivals, often middle-aged, and are mostly attracted by the tropical climate.

South America[]

The majority of Dutch settlement in South America was limited to Suriname,[46] however, only 86,000 Dutch descents are found in the country. Sizable Dutch-descendant communities exist in urban areas and coastal port towns, mainly in Brazil,[47] but also with significant numbers in Chile and Guyana.[48][49]

Brazil[]

The first and largest wave of Dutch settlers in Brazil was between 1640 and 1656. A Dutch colony was established in Northeast Brazil; over 30.000 people settled in the region. When the Portuguese Empire invaded the colony, most of the Dutch settlers went to areas further inland and changed their surnames to Portuguese ones. Today, descendants live in the states of Pernambuco, Ceará, Paraíba, and Rio Grande Norte. The number of descendants is unknown, but genetic studies showed a strong presence of Northern European haplogroups in Brazilians of this region. Only Southern Brazil showed to have more Nordic DNA because the region was populated by German immigrants. Other Dutch settlers left and migrated to Caribbean; others who left are Dutch Jewish settlers and Dutch-speaking Portuguese settlers.

After two centuries, many Dutch immigrants to Brazil went to the state of Espírito Santo between 1858 and 1862. All further immigration ceased and contacts with the homeland withered. The "lost settlement" was only rediscovered after several years, in 1873. Except for the Zeelanders in Holanda, Brazil attracted few Dutch until after 1900. From 1906 through 1913, over 3.500 Dutch emigrated there, mainly in 1908–1909.[50] It is estimated that over 1,000,000 people in Brazil have full or partial Dutch ancestry.[47]

After the Second World War, the Dutch Organization of Catholic Farmers and Vegetable Growers (KNBTB) coordinated a new flow of Dutch immigrants in search for a new life and new opportunities in Brazil.

Chile[]

The emigration from the Netherlands to Chile was in 1895. A dozen Dutch families settled between 1895 and 1897 in Chiloé Island. In the same period Egbert Hageman arrived in Chile.[51] With his family, 14 April 1896, settling in Rio Gato, near Puerto Montt. In addition, family Wennekool which inaugurated the Dutch colonization of Villarrica.[52]

On 4 May 1903, a group of over 200 Dutch emigrants sailed on the steamship "Oropesa" shipping company "Pacific Steam Navigation Company", from La Rochelle (La Pallice) in France. The majority of migrants were born in the Netherlands: 35% was from North Holland and South Holland, 13% of North Brabant, 9% of Zeeland and equal number of Gelderland.

On 5 June, they arrived by train to their final destination, the city of Pitrufquén, located south of Temuco, near the hamlet of Donguil. Another group of Dutchmen arrived shortly after to Talcahuano, in the "Oravi" and the "Orissa". The Dutch colony in Donguil was christened "New Transvaal Colony". There, more than 500 families settled in order to start a new life. Between 7 February 1907 and 18 February 1909 it is estimated that about 3,000 Boers arrived in Chile.

It is estimated that as many as 10,000 Chileans are of Dutch descent, most of them located in Malleco, Gorbea, Pitrufquén, Faja Maisan and around Temuco.[53][49]

Suriname[]

Dutch migrant settlers in search of a better life started arriving in Suriname (previously known as Dutch Guiana) in the 19th century with the boeroes (not to be confused with the South African Boeren), farmers arriving from the Dutch provinces of Gelderland and Groningen.[54] Many Dutch settlers left Suriname after independence in 1975. Furthermore, the Surinamese ethnic group Creoles, persons of mixed African-European ancestry, are partially of Dutch descent.

Australia[]

Although the Dutch were the first Europeans to reach Australia,[55] they have never made a great impact as a group of settlers. At the time of Australia's discovery the Dutch were on the winning hand in their war against Spain and as a result there was little religious persecution. They did not find the kind of opportunities for trade they had learned to expect in the Dutch East Indies. In the Dutch Golden Age regions with high unemployment were also rare. Indeed, the Dutch Republic was an immigration country itself throughout the 17th century. As a result, there never was the kind of mass emigration by the Dutch similar to that of the Irish, Germans, Italians or by comparison, Yugoslavians. Only after the Second World War was there significant migration from the Netherlands to Australia. This certainly does not mean that they have not made a contribution to Australia. As individuals many have made an impressive and lasting contribution to their adopted country.[56]

New Zealand[]

Dutchman Abel Tasman was the first European to sight New Zealand in December 1642, though he was attacked by Māori before he could land in the area at the northwestern tip of the South Island now known as Golden Bay. As a result, the nation was subsequently named Nieuw-Zeeland by Dutch cartographers after the Dutch province of Zeeland.

The modern migration of the Dutch to New Zealand started in the 1950s. Those Dutch settlers came from present-day Indonesia when it won independence and majority of Dutch settlers left their homes in Indonesia.[57][58] Many of them were hard-working and achieved success, among other activities, in agriculture (particularly growing of tulips) and in hospitality. According to the 2006 census results, over 20,000 inhabitants of New Zealand were Dutch born.[59]

United Kingdom[]

The 2001 UK Census recorded 40,438 Dutch-born people living in the UK.[60] The 2011 Census recorded 57,439 Dutch-born residents in England, 1,642 in Wales,[61] 4,117 in Scotland and 515 in Northern Ireland.[62][63] The Office for National Statistics estimates that the figure for the whole of the UK was 68,000 in 2019.[64]

Indonesia[]

In the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), the Dutch heavily interacted with the indigenous population, and as European women were almost non-existent, many Dutchmen married native women. This created a new group of people, the Dutch-Eurasians (Dutch: Indische Nederlanders) also known as 'Indos' or 'Indo-Europeans'. By 1930, there were more than 240,000 Europeans and 'Indo-Europeans' in the colony.[65] After the Indonesian National Revolution many chose or were forced to leave the country and today about half a million Eurasians live in the Netherlands.

Although there are some who decided to take side with Indonesian, such as Poncke Princen, or joining Indonesian army after full sovereignty handover in 1950 such as Rokus Bernardus Visser.

With the booming of Indonesian economy in the 1970s and 1980s, some Dutch people decided to move to Indonesia, either as an expatriate who work on a temporary basis, or even staying permanently. One of them is Erik Meijer who have distinguished career with Indosat and Garuda Indonesia.[66]

Spain[]

According to the Spanish National Institute of Statistics, on 1 January 2020, 46.735 Dutch were living in that country.[67]

Turkey[]

About 20,000 Dutch live in Turkey, mostly pensioners. The Dutch populated areas are mainly in the Marmara, Aegean, and Mediterranean regions of Turkey.[68]

Japan[]

The Dutch are a small unknown minority living in Japan. The first known Dutch person of Japanese descent is Ludovicus Stornebrink. Mike Havenaar is a well known Japanese professional footballer of Dutch descent.

List of countries by population of Dutch heritage[]

| Country | Population | % of country | Criterion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dutch in North America | |||

| 1,067,245 | 3% | ||

| 5,023,846 | 1.6% | ||

| Dutch in South America | |||

| Whites and non-whites descended from Dutch. 1,000,000 | 0.5% | ||

| 10,000 | 0.3% | ||

| 5,000 | 0.07% | ||

| Dutch in Europe | |||

| 40,438 | 0.06% | ||

| 2,000 | 0.04% | [71] | |

| Dutch ancestry 1,000,000, born in The Netherlands 60,000 [72] | 1.5% | ||

| 350,000 | 0.4% | ||

| 120,970 | 1% | ||

| 53,000 | |||

| Dutch in Asia | |||

| 40,000 | 0.3% | ||

| Dutch in Oceania | |||

| 335,493 | 1.5% | ||

| 100,000 | 2% | ||

| Dutch in Africa | |||

| 50,000 | 2.5% | ||

| 4,539,790 | |||

| 2,710,461 | 5.4% | ||

| Total in Diaspora | ~15,000,000 | ||

| 17,151,228 | % | ||

| Total Worldwide | ~28,000,000 |

See also[]

- Afrikaner

- Boer

- Demographics of the Netherlands

- List of Dutch people

- History of the Netherlands

- Diaspora

- Indo (Eurasian)

References[]

- ^ a b c d e f Nicholaas, Han; Sprangers, Arno. "Dutch-born 2001, Figure 3 in DEMOS, 21, 4. Nederlanders over de grens" (PDF). Nidi.knaw.nl. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2007. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ^ a b Wiarda, Howard (2007). The Dutch Diaspora: The Netherlands and Its Settlements in Africa, Asia, and the Americas. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0739121054.

- ^ Dutch immigration to Germany. (Dutch)

- ^ Onbekende Buren, by Dik Linthout, page 102/103.

- ^ "Nymburk". Radio Praha. 13 December 2006.

- ^ "Spread of the Dutch world wide" (PDF). Nidi.knaw.nl. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2009. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Hunt, John (2005). Campbell, Heather-Ann (ed.). Dutch South Africa: Early Settlers at the Cape, 1652-1708. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 13–35. ISBN 978-1904744955.

- ^ Parthesius, Robert (2010). Dutch Ships in Tropical Waters: The Development of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) Shipping Network in Asia 1595-1660. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-9053565179.

- ^ Lucas, Gavin (2004). An Archaeology of Colonial Identity: Power and Material Culture in the Dwars Valley, South Africa. New York: Springer, Publishers. pp. 29–33. ISBN 978-0306485381.

- ^ Ward, Kerry (2009). Networks of Empire: Forced Migration in the Dutch East India Company. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 322–342. ISBN 978-0-521-88586-7.

- ^ a b Thomason, Sarah Grey; Kaufman, Terrence (1988), Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics, University of California Press (published 1991), pp. 252–254, ISBN 978-0-520-07893-2

- ^ Worden, Nigel (2010). Slavery in Dutch South Africa (2010 ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 40–43. ISBN 978-0521152662.

- ^ a b Entry: Cape Colony. Encyclopædia Britannica Volume 4 Part 2: Brain to Casting. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1933. James Louis Garvin, editor.

- ^ a b Colenbrander, Herman. De Afkomst Der Boeren (1902). Kessinger Publishing 2010. ISBN 978-1167481994.

- ^ Mbenga, Bernard; Giliomee, Hermann (2007). New History of South Africa. Cape Town: Tafelburg, Publishers. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-0624043591.

- ^ S. W. Martin, Faith Negotiating Loyalties: An Exploration of South African Christianity Through a Reading of the Theology of H. Richard Niebuhr (University Press of America, 2008), ISBN 0761841113, pp. 53-54.

- ^ a b Lloyd, Trevor Owen (1997). The British Empire, 1558-1995. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 201–206. ISBN 978-0198731337.

- ^ a b c d Ross, Robert (1999). Status and Respectability in the Cape Colony, 1750–1870: A Tragedy of Manners. Philadelphia: Cambridge University Press. pp. 47–58. ISBN 978-0521621229.

- ^ Afọlayan, Funso (1997). Culture and Customs of South Africa. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0313320187.

- ^ Abulof, Uriel (2015). The Mortality and Morality of Nations. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 232. ISBN 9781107097070.

- ^ Greaves, Adrian (2 September 2014). The Tribe that Washed its Spears: The Zulus at War (2013 ed.). Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. pp. 36–55. ISBN 978-1629145136.

- ^ Giliomee, Hermann (1991). The Creation of Tribalism in Southern Africa. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 21–28. ISBN 978-0520074200.

- ^ Moffett, Samuel H. (1998). A History of Christianity in Asia: 1500-1900. Bishop Henry McNeal Turner Studies in North American Black Religion Series. Vol. Volume 2 of A History of Christianity in Asia: 1500-1900. Volume 2 (2nd, illustrated, reprint ed.). Orbis Books. p. 222. ISBN 978-1570754500. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Moffett, Samuel H. (2005). A history of Christianity in Asia, Volume 2 (2nd ed.). Orbis Books. p. 222. ISBN 978-1570754500. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Free China Review, Volume 11. W.Y. Tsao. 1961. p. 54. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Manthorpe, Jonathan (2008). Forbidden Nation: A History of Taiwan (illustrated ed.). Macmillan. p. 77. ISBN 978-0230614246. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Covell, Ralph R. (1998). Pentecost of the Hills in Taiwan: The Christian Faith Among the Original Inhabitants (illustrated ed.). Hope Publishing House. p. 96. ISBN 978-0932727909. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Manthorpe, Jonathan (2008). Forbidden Nation: A History of Taiwan (illustrated ed.). Macmillan. p. 77. ISBN 978-0230614246. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Covell, Ralph R. (1998). Pentecost of the Hills in Taiwan: The Christian Faith Among the Original Inhabitants (illustrated ed.). Hope Publishing House. p. 96. ISBN 978-0932727909. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Lach, Donald F.; Van Kley, Edwin J. (1998). Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume III: A Century of Advance. Book 4: East Asia. Vol. Asia in the Making of Europe Volume III (revised ed.). University of Chicago Press. p. 1823. ISBN 978-0226467696. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Manthorpe, Jonathan (2008). Forbidden Nation: A History of Taiwan (illustrated ed.). Macmillan. p. 72. ISBN 978-0230614246. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Manthorpe, Jonathan (2008). Forbidden Nation: A History of Taiwan (illustrated ed.). Macmillan. p. 77. ISBN 978-0230614246. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Heaver, Stuart (26 February 2012). "Idol worship". South China Morning Post. p. 25. Archived from the original on 29 December 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014. Alt URL

- ^ Manthorpe, Jonathan (2008). Forbidden Nation: A History of Taiwan (illustrated ed.). Macmillan. p. 77. ISBN 978-0230614246. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Wright, Arnold, ed. (1909). Twentieth century impressions of Netherlands India: Its history, people, commerce, industries and resources (illustrated ed.). Lloyd's Greater Britain Pub. Co. p. 67. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Newman, Bernard (1961). Far Eastern Journey: Across India and Pakistan to Formosa. H. Jenkins. p. 169. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Muller, Hendrik Pieter Nicolaas (1917). Onze vaderen in China (in Dutch). P.N. van Kampen. p. 337. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Potgieter, Everhardus Johannes; Buijis, Johan Theodoor; van Hall, Jakob Nikolaas; Muller, Pieter Nicolaas; Quack, Hendrik Peter Godfried (1917). De Gids, Volume 81, Part 1 (in Dutch). G. J. A. Beijerinck. p. 337. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ de Zeeuw, P. (1924). De Hollanders op Formosa, 1624-1662: een bladzijde uit onze kolonialeen zendingsgeschiedenis (in Dutch). W. Kirchner. p. 50. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Algemeene konst- en letterbode, Volume 2 (in Dutch). A. Loosjes. 1851. p. 120. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Reid, Anthony (1990). Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450–1680: The lands below the winds. Vol. Volume 1 of Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450–1680 (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-300-04750-9.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Hamilton, Alexander (1997). Smithies, Michael (ed.). Alexander Hamilton: A Scottish Sea Captain in Southeast Asia, 1689–1723 (illustrated, reprint ed.). Silkworm Books. p. 205. ISBN 978-9747100457.

- ^ "Article on Dutch-Canadians". Aadstravelbooks.com. Archived from the original on 22 January 2009. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "According to the 1991 census". Aadstravelbooks.com. Archived from the original on 22 January 2009. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity Highlight Tables - Ethnic Origin, both sexes, age (total), Canada, 2016 Census – 25% Sample data". 25 October 2017.

- ^ Suriname. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency

- ^ a b "Curiosidades sobre os holandeses no Brasil". 4 September 2015.

- ^ "Antropología Experimental" (PDF). Ujaen.es. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ a b "A principios del siglo XX". Members.tripod.com. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "United States and Brazil: The Defeat of the Dutch / Brasil e Estados Unidos: A Expulsão dos Holandeses do Brasil". lcweb2.loc.gov. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "A principios del siglo XX". Members.tripod.com. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "A principios del siglo XX". Members.tripod.com. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d "CST&T". 3 July 2013. Archived from the original on 18 August 2013.

- ^ America Desde Otra Frontera. La Guayana Holandesa - Surinam : 1680-1795, Ana Crespo Solana.

- ^ "Early Dutch Landfall Discoveries of Australia". Muffley.net. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ Klaassen, Nic. "Dutch settlers in South Australia". Southaustralianhistory.com.au. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "2. – Dutch – Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand".

- ^ Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "Settlement". teara.govt.nz.

- ^ "Page 4. The Dutch contribution". Teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ a b "Country-of-birth database". Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Archived from the original on 17 June 2009. Retrieved 3 February 2009.

- ^ "Table QS213EW 2011 Census: Country of birth (expanded), regions in England and Wales". Office for National Statistics. 26 March 2013. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ^ "Country of birth (detailed)" (PDF). National Records of Scotland. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ^ "Country of Birth - Full Detail: QS206NI". Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ^ "Table 1.3: Overseas-born population in the United Kingdom, excluding some residents in communal establishments, by sex, by country of birth, January 2019 to December 2019". Office for National Statistics. 21 May 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2020. Figure given is the central estimate. See the source for 95% confidence intervals.

- ^ Beck, Sanderson, South Asia, 1800–1950 – World Peace Communications (2008) ISBN 978-0-9792532-3-2 By 1930 more European women had arrived in the colony, and they made up 113,000 out of the 240,000 Europeans.

- ^ "Erik Meijer: A Dutch marketing maverick learns the lingo of RI telecommunication..." Thejakartapost.com. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "INE.es". Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b Nicholaas, Han; Sprangers, Arno. "210,000 emigrants since World War II, after return migration there were 120,000 Netherlands-born residents in Canada in 2001. DEMOS, 21, 4. Nederlanders over de grens". Nidi.knaw.nl. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2007.

- ^ Nicholaas, Han; Sprangers, Arno. "Dutch-born 2001, Figure 3 in DEMOS, 21, 4. Nederlanders over de grens". Nidi.knaw.nl. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2007.

- ^ "Immigrant and Emigrant Populations by Country of Origin and Destination". migrationpolicy.org. 10 February 2014.

- ^ étrangères, Ministère de l'Europe et des Affaires. "Présentation des Pays-Bas". France Diplomatie - Ministère de l'Europe et des Affaires étrangères.

- ^ "Federal Statistics Office - Foreign population". Archived from the original on 12 February 2012.

- ^ "Number of people with the Dutch nationality in Belgium as reported by Statistic Netherlands" (PDF). Cbs.nl (in Dutch). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "Table 5 Persons with immigrant background by immigration category, country background and sex. 1 January 2009". Ssb.no. 1 January 2009. Archived from the original on 15 November 2011. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ^ Joshua Project. "Dutch Ethnic People in all Countries". Joshua Project. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ^ "銀座カラー口コミベスト!6つのメリット・2つのデメリットから徹底解説!". Dutchburgherunion.org. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "ABS Ancestry". 2012.

- ^ "New Zealand government website on Dutch-Australians". Teara.govt.nz. 4 March 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ Nunuhe, Margreth (18 February 2013). "Rehoboth community in danger of extinction". New Era. Archived from the original on 13 April 2013.

- ^ Coloured population.

- ^ Afrikaner population.

- ^ "The World Factbook – Netherlands". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

External links[]

- NLBorrels A global network for Dutch Expatriates

- Historical articles about Dutch emigration after WWII (in English and Dutch)

- Dutch diaspora

- Human migration

- European diasporas