Economic sanctions

| Part of a series on |

| World trade |

|---|

|

Economic sanctions are commercial and financial penalties applied by one or more countries against a targeted self-governing state, group, or individual.[1] Economic sanctions are not necessarily imposed because of economic circumstances—they may also be imposed for a variety of political, military, and social issues. Economic sanctions can be used for achieving domestic and international purposes.[2][3][4]

Economic sanctions generally aim to create good relationships between the country enforcing the sanctions and the receiver of said sanctions. However, the efficacy of sanctions is debatable and sanctions can have unintended consequences.[5]

Economic sanctions may include various forms of trade barriers, tariffs, and restrictions on financial transactions.[6] An embargo is similar, but usually implies a more severe sanction, often with a direct no-fly zone or naval blockade.

An embargo (from the Spanish embargo, meaning hindrance, obstruction, etc. in a general sense, a trading ban in trade terminology and literally "distraint" in juridic parlance) is the partial or complete prohibition of commerce and trade with a particular country/state or a group of countries.[7] Embargoes are considered strong diplomatic measures imposed in an effort, by the imposing country, to elicit a given national-interest result from the country on which it is imposed. Embargoes are generally considered legal barriers to trade, not to be confused with blockades, which are often considered to be acts of war.[8] Embargoes can mean limiting or banning export or import, creating quotas for quantity, imposing special tolls, taxes, banning freight or transport vehicles, freezing or seizing freights, assets, bank accounts, limiting the transport of particular technologies or products (high-tech) for example CoCom during the cold-war.[9] In response to embargoes, a closed economy or autarky often develops in an area subjected to heavy embargo. Effectiveness of embargoes is thus in proportion to the extent and degree of international participation. Embargoes can be an opportunity to some countries to develop faster a self-sufficiency. However, Embargo may be necessary in various economic situations of the State forced to impose it, not necessarily therefore in case of war.

Politics of sanctions[]

Economic sanctions are used as a tool of foreign policy by many governments. Economic sanctions are usually imposed by a larger country upon a smaller country for one of two reasons: either the latter is a perceived threat to the security of the former nation or that country treats its citizens unfairly. They can be used as a coercive measure for achieving particular policy goals related to trade or for humanitarian violations. Economic sanctions are used as an alternative weapon instead of going to war to achieve desired outcomes.

Effectiveness of economic sanctions[]

Hufbauer, Schott, and Elliot (2008) argue that regime change is the most frequent foreign-policy objective of economic sanctions, accounting for just over 39 percent of cases of their imposition.[10] Hufbauer et al. claimed that in their studies that 34 percent of the cases were successful.[11] When Robert A. Pape examined their study, he claimed that only five of their forty so-called "successes" stood up,[12] reducing the success rate to 4%. Success of sanctions as a form of measuring effectiveness has also been widely debated by scholars of economic sanctions.[vague][13] Success of a single sanctions-resolution does not automatically lead to effectiveness, unless the stated objective of the sanctions regime is clearly identified and reached.

According to a study by Neuenkirc and Neumeier (2015)[14] the US and UN economic sanctions had a statistically significant impact on the target country's economy by reducing GDP growth by more than 2 percent a year. The study also concluded that the negative effects typically last for a period of ten years amounting to an aggregate decline in the target country's GDP per-capita of 25.5 percent.[14]

Imposing sanctions on an opponent also affects the economy of the imposing country to some degree. If import restrictions are promulgated, consumers in the imposing country may have restricted choices of goods. If export restrictions are imposed or if sanctions prohibit companies in the imposing country from trading with the target country, the imposing country may lose markets and investment opportunities to competing countries.[15] Critics of sanctions like Belgian jurist Marc Bossuyt, however, argue that in nondemocratic regimes, the extent to which this affects political outcomes is contested, because by definition such regimes do not respond as strongly to the popular will.[16]

British diplomat Jeremy Greenstock suggests sanctions are popular not because they are known to be effective, but because "there is nothing else [to do] between words and military action if you want to bring pressure upon a government".[17]

A strong connection has been found between the effectiveness of sanctions and the size of veto players in a government. Veto players represent individual or collective actors whose agreement is required for a change of the status quo, for example - parties in a coalition, or the legislature's check on presidential powers. When sanctions are imposed on a country, it can try to mitigate them by adjusting its economic policy. The size of the veto players determines how many constraints the government will face when trying to change status quo policies, and the larger the size of the veto players, the more difficult it is to find support for new policies, thus making the sanctions more effective.[18]

Criticism[]

Sanctions have been criticized on humanitarian grounds, as they negatively impact a nation's economy and can also cause collateral damage on ordinary citizens. Peksen implies that sanctions can degenerate human rights in the target country.[19] Some policy analysts believe imposing trade restrictions only serves to hurt ordinary people as opposed to government elites,[20][21][22][23] and others have likened the practice to siege warfare.[24][25]

History of sanctions[]

The use of economic sanctions became much more common in the 20th century, particularly with the formation of The League of Nations in 1919. The Abyssinia Crisis resulted in League sanctions against Mussolini's Italy in 1935 under Article 16 of the Covenant.[26] Petroleum supplies, however, were not stopped, nor the Suez Canal closed to Italy, and the conquest proceeded. The sanctions were lifted in 1936 and Italy left the League in 1937.[27] After World War Two, the League was replaced by the more expansive United Nations in 1945.

Sanctions have become a commonly used foreign policy tool in the 21st century in countless situations ranging from disputes to hostile confrontations.[28]

Implications for businesses[]

There is an importance, especially with relation to financial loss, for companies to be aware of embargoes that apply to their intended export or import destinations[29]. Properly preparing products for trade, sometimes referred to as an embargo check, is a difficult and timely process for both importers and exporters.[30]

There are many steps that must be taken to ensure that a business entity does not accrue unwanted or fines, taxes, or other punitive measures[31]. Common examples of embargo checks include referencing embargo lists,[32][33][34] cancelling transactions, and ensuring the validity of a trade entity.[35]

This process can become very complicated, especially for countries with changing embargoes. Before better tools became available, many companies relied on spreadsheets and manual processes to keep track of compliance issues. Today, there are software based solutions that automatically handle sanctions and other complications with trade.[36][37][38]

Examples[]

United States Sanctions[]

US Embargo of 1807[]

The United States Embargo of 1807 involved a series of laws passed by the U.S. Congress (1806–1808) during the second term of President Thomas Jefferson.[39] Britain and France were engaged in the War of the Fourth Coalition; the U.S. wanted to remain neutral and to trade with both sides, but both countries objected to American trade with the other.[40] American policy aimed to use the new laws to avoid war and to force both France and Britain to respect American rights.[41] The embargo failed to achieve its aims, and Jefferson repealed the legislation in March 1809.

US Embargo of Cuba[]

The United States embargo against Cuba began on March 14, 1958, during the rule of dictator Fulgencio Batista. At first, the embargo applied only to arms sales, however it later expanded to include other imports, eventually extending to almost all trade on February 7, 1962.[42] Referred to by Cuba as "el bloqueo" (the blockade),[43] the U.S. embargo on Cuba remains as of 2021 one of the longest-standing embargoes in modern history.[44] Few of the United States' allies embraced the embargo, and many have argued it has been ineffective in changing Cuban government behavior.[45] While taking some steps to allow limited economic exchanges with Cuba, American President Barack Obama nevertheless reaffirmed the policy in 2011, stating that without the granting of improved human rights and freedoms by Cuba's current government, the embargo remains "in the national interest of the United States".[46]

Russian sanctions[]

Russia has been known to utilize economic sanctions to achieve its political goals. Russia's focus has been primarily on implementing sanctions against the pro-Western governments of former Soviet Union states. The Kremlin's aim is particularly on states that aspire to join the European Union and NATO, such as Serbia, Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia.[47]

Russia sanctions on Ukraine[]

Viktor Yushcenko, the third president of Ukraine who was elected in 2004, lobbied during his term to gain admission to NATO and the EU.[48] Soon after Yushchenko entered office, Russia demanded Kyiv pay the same rate that it charged Western European states. This quadrupled Ukraine's energy bill overnight.[48] Russia subsequently cut off the supply of natural gas in 2006, causing significant harm to the Ukrainian and Russian economies.[49] As the Ukrainian economy began to struggle, Yushcenko's approval ratings dropped significantly; reaching the single digits by the 2010 election; Viktor Yanukovych, who was more supportive of Moscow won the election in 2010 to become the fourth president of Ukraine. After his election, gas prices were reduced substantially.[48]

Russian sanctions on Georgia[]

The Rose Revolution in Georgia brought Mikheil Saakashvili to power as the third president of the country. Saakashvili wanted to bring Georgia into NATO and the EU and was a strong supporter of the U.S.-led war in Iraq and Afghanistan.[50] Russia would soon implement a number of different sanctions on Georgia, including natural gas price raises through Gazprom and wider trade sanctions that impacted the Georgian economy, particularly Georgian exports of wine, citrus fruits, and mineral water. In 2006, Russia banned all imports from Georgia which was able to deal a significant blow to the Georgian economy.[50] Russia also expelled nearly 2,300 Georgian who worked within its borders.[50]

United Nations sanctions[]

The United Nations issues sanctions by consent of the Security Council and/or General Assembly in response to major international events, receiving authority to do so under Article 41 of Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter.[51] The nature of these sanctions may vary, and include financial, trade, or weaponry restrictions. Motivations can also vary, ranging from humanitarian and environmental concerns[52] to efforts to halt nuclear proliferation. Over two dozen sanctions measures have been implemented by the United Nations since its founding in 1945.[51]

Sanctions on Somalia, 1992[]

The UN implemented sanctions against Somalia beginning in April 1992, after the overthrow of the Siad Barre led coup in 1991 during the Somali Civil War. United Nations Security Council Resolution 751 forbade members to sell, finance, or transfer any military equipment to Somalia.[53]

Sanctions on North Korea, 2006-present[]

The United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 1718 in 2006 in response to a nuclear test that the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) conducted in violation of the Treaty on Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. The resolution banned the sale of military and luxury goods and froze government assets.[54] Since then, the United Nations has passed multiple resolutions subsequently expanding sanctions on North Korea. Resolution 2270 from 2016 placed restrictions on transport personnel and vehicles employed by North Korea while also restricting the sale of natural resources and fuel for aircraft.[55]

The efficacy of such sanctions has been questioned in light of continued nuclear tests by North Korea in the decade following the 2006 resolution. Professor William Brown of Georgetown University argued that "sanctions don't have much of an impact on an economy that has been essentially bankrupt for a generation".[56]

Sanctions on Libya[]

On February 26, 2011, the Security Council of the United Nations issued an arms embargo against the Libya through Security Council Resolution 1970 in response to humanitarian abuses occurring in the First Libyan Civil War.[57] The embargo was later extended to mid-2018. Under the embargo, Libya has suffered serve inflation because of increased dependence on the private sector to import goods.[58] The sanctions caused large cuts to health and education, which caused social conditions to decrease. Even though the sanctions were in response to human rights, their effects were limited.[59]

Sanctions on apartheid South Africa[]

In effort to punish South Africa for its policies of apartheid, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a voluntary international oil-embargo against South Africa on November 20, 1987; that embargo had the support of 130 countries.[60] South Africa, in response, expanded its Sasol production of synthetic crude.[61]

Other multilateral sanctions[]

One of the most comprehensive attempts at an embargo occurred during the Napoleonic Wars of 1803–1815. Aiming to cripple the United Kingdom economically, Emperor Napoleon I of France in 1806 promulgated the Continental System – which forbade European nations from trading with the UK. In practice the French Empire could not completely enforce the embargo, which proved as harmful (if not more so) to the continental nations involved as to the British.[62]

The United States, Britain, the Republic of China and the Netherlands imposed sanctions against Japan in 1940–1941 in response to its expansionism. Deprived of access to vital oil, iron-ore and steel supplies, Japan started planning for military action to seize the resource-rich Dutch East Indies, which required a preemptive attack on Pearl Harbor, triggering the American entry into the Pacific War.[63]

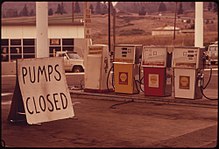

In 1973–1974, OAPEC instigated the 1973 oil crisis through its oil embargo against the United States and other industrialized nations that supported Israel in the Yom Kippur War. The results included a sharp rise in oil prices and in OPEC revenues, an emergency period of energy rationing, a global economic recession, large-scale conservation efforts, and long-lasting shifts toward natural gas, ethanol, nuclear and other alternative energy sources.[64][65] Israel continued to receive Western support, however.

Current sanctions[]

This list is incomplete; you can help by . (January 2015) |

By targeted country[]

- China (by EU and US), arms embargo, enacted in response to the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989.[66]

- European Union arms embargo on the People's Republic of China.

- Hong Kong, enacted in response to the National Security law.

- Cuba (United States embargo against Cuba), arms, consumer goods, money, enacted 1958.

- EU, US, Australia, Canada and Norway (by Russia) since August 2014, beef, pork, fruit and vegetable produce, poultry, fish, cheese, milk and dairy.[67] On August 13, 2015, the embargo was expanded to Albania, Montenegro, Iceland, and Liechtenstein.[68][69]

- Gaza Strip by Israel since 2001, under arms blockade since 2007 due to the large number of illicit arms traffic used to wage war, (occupied officially from 1967 to 2005).

- Indonesia (by Australia), live cattle because of cruel slaughter methods in Indonesia.[70]

- Iran: by US and its allies, notably bar nuclear, missile and many military exports to Iran and target investments in: oil, gas and petrochemicals, exports of refined petroleum products, banks, insurance, financial institutions, and shipping.[71] Enacted 1979, increased through the following years and reached its tightest point in 2010.[72] In April 2019 the U.S. threatened to sanction countries continuing to buy oil from Iran after an initial six-month waiver announced in November 2018 expired.[73] According to the BBC, U.S. sanctions against Iran "have led to a sharp downturn in Iran's economy, pushing the value of its currency to record lows, quadrupling its annual inflation rate, driving away foreign investors, and triggering protests."[74]

- Japan,[who?] animal shipments due to lack of infrastructure and radiation issue after the 2011 Tohoku earthquake aftermath.

- Myanmar – the European Union's sanctions against Myanmar (Burma), based on lack of democracy and human rights infringements.[75]

- North Korea

- international sanctions imposed on North Korea since the Korean War of 1950–1953 eased under the Sunshine Policy of South Korean President Kim Dae Jung and of U.S. President Bill Clinton.[76] but tightened again in 2010.[77]

- by UN, USA, EU,[78] luxury goods (and arms), enacted 2006.

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 1718 (2006) – a reaction to the DPRK's claim of a nuclear test.

- Qatar by surrounding countries including Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Egypt.

- Russia: On August 2, 2017, President Donald Trump signed into law the Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act that grouped together sanctions against Russia, Iran and North Korea.[79][80]

- Sudan by US since 1997.

- Syria (by EU, US), arms and imports of oil.[81]

- Taiwan, enacted in response to United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2758 and weapons of mass destruction program.

- Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, (by UN), consumer goods, enacted 1975.

- Venezuela, by EU, US, since 2015,[82][83] arms embargo and selling of assets banned due to human rights violations, high government corruption, links with drug cartels and electoral rigging in the 2018 Venezuelan presidential elections;[84][85] Canada since 2017;[86][87][88] and since 2018, Mexico,[89] Panama[90] and Switzerland.[91]

By targeted individuals[]

- List of individuals sanctioned during the 2013–15 Ukrainian crisis

- List of individuals sanctioned during the Venezuelan crisis

- There is a United Nations sanction imposed by UN Security Council Resolution 1267 in 1999 against all Al-Qaida- and Taliban-associated individuals. The cornerstone of the sanction is a consolidated list of persons maintained by the Security Council. All nations are obliged to freeze bank accounts and other financial instruments controlled by or used for the benefit of anyone on the list.

By sanctioning country[]

- United States embargoes

- The 2002 United States steel tariff was placed by the United States on steel to protect its industry from foreign producers such as China and Russia. The World Trade Organization ruled that the tariffs were illegal. The European Union threatened retaliatory tariffs on a range of US goods that would mainly affect swing states. The US government then removed the steel tariffs in early 2004.

By targeted activity[]

- In response to cyber-attacks on April 1, 2015, President Obama issued an Executive Order establishing the first-ever economic sanctions. The Executive Order was intended to impact individuals and entities (“designees”) responsible for cyber-attacks that threaten the national security, foreign policy, economic health, or financial stability of the US. Specifically, the Executive Order authorized the Treasury Department to freeze designees’ assets.[92] The European Union implemented their first targeted financial sanctions regarding cyber activity in 2020.[93]

- In response to intelligence analysis alleging Russian hacking and interference with the 2016 U.S. elections, President Obama expanded presidential authority to sanction in response to cyber activity that threatens democratic elections.[94] Given that the original order was intended to protect critical infrastructure, it can be argued that the election process should have been included in the original order.

Bilateral trade disputes[]

- Vietnam as a result of capitalist influences over the 1990s and having imposed sanctions against Cambodia, is accepting of sanctions disposed with accountability.[clarification needed]

- In March 2010, Brazil introduced sanctions against the US. These sanctions were placed because the US government was paying cotton farmers for their products against World Trade Organization rules. The sanctions cover cotton, as well as cars, chewing gum, fruit, and vegetable products.[95] The WTO is currently supervising talks between the states to remove the sanctions.[citation needed]

EU Sanctions[]

In March 2021, Reuters reported that the EU has put immediate sanctions on both Chechnya and Russia - due to ongoing government sponsored and backed violence against LGBTIQ+ individuals.[96]

Former sanctions[]

- Arab boycott of Israel

- 2006–07 economic sanctions against the Palestinian National Authority

- Sanctions against Iraq (1990–2003)

- Disinvestment from South Africa

- ABCD line, against Japan before WWII

- Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (by the UN)

- Trade embargo against North Vietnam (1964–1975) and unified Vietnam (1975–1994) by the US [97]

- Republic of Macedonia, complete trade embargo by Greece (1994-1995)

- Libya (by the United Nations), weapons, enacted 2011 after mass killings of Libyan protesters/rebels. Ended later that year after the overthrow and summary execution of Gaddafi.

- India (by UK),[98] nuclear exports restriction

- Mali (by ECOWAS) total embargo in order to force Juntas to give power back and re-install National constitution. Decided on April 2, 2012.[99] [100]

- Pakistan (by UK),[98] nuclear exports restriction, enacted 2002.

- Serbia by Kosovo's unilaterally declared government, since 2011.[101]

- Embargo Act of 1807

- Former Yugoslavia Embargo November 21, 1995 Dayton Peace Accord

- Georgia (by Russia), agricultural products, wine, mineral water, enacted 2006, lifted 2013.[102]

- United States embargo against Nicaragua

- CoCom

- Italy by League of Nations (October 1935) after the Italian invasion of Abyssinia

See also[]

- Arms embargo

- Boycott

- International sanctions

- Specially Designated National

- Non-tariff barriers to trade

- Oil embargo

- United States embargoes

- Political economy

- Trade war

- Hegemony

- Individual and group rights

- Economic freedom

- Globalization

- Dima Yakovlev Law

- Magnitsky Act

- Interdict (Catholic canon law)

Further reading[]

- The Global Sanctions Data Base.[103][104]

- Daniel W. Drezner. 1999. The Sanctions Paradox. Cambridge University Press.

- Nicholas Mulder. 2022. The Economic Weapon: The Rise of Sanctions as a Tool of Modern War. Yale University Press.

References[]

- ^ Lin, Tom C. W. (2016-04-14). "Financial Weapons of War". Rochester, NY. SSRN 2765010. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Whang, Taehee (2011-09-01). "Playing to the Home Crowd? Symbolic Use of Economic Sanctions in ..." International Studies Quarterly. Ingentaconnect.com. 55 (3): 787–801. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2478.2011.00668.x. Retrieved 2015-03-30.

- ^ [2] Archived August 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lee, Yong Suk (2018). "Lee, Yong Suk, 2018. "International isolation and regional inequality: Evidence from sanctions on North Korea," Journal of Urban Economics". Journal of Urban Economics. 103 (C): 34–51. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2017.11.002. S2CID 158561662.

- ^ Haidar, J.I., 2015."Sanctions and Exports Deflection: Evidence from Iran," Paris School of Economics, University of Paris 1 Pantheon Sorbonne, Mimeo

- ^ University of California, Irvine (April 8, 2013). "Trade Embargoes Summary". darwin.bio.uci.edu.

- ^ "Blockade as Act of War". Crimes of War Project. Archived from the original on 2012-06-18. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- ^ Palánkai, Tibor. "Investor-partner Business dictionary".

- ^

Hufbauer, Gary Clyde; Schott, Jeffrey J.; Elliott, Kimberly Ann; Oegg, Barbara (2008). Economic Sanctions Reconsidered (3 ed.). Washington, DC: Columbia University Press. p. 67. ISBN 9780881324822. Retrieved 2018-05-10.

By far, regime change is the most frequent foreign policy objective of economic sanctions, accounting for 80 out of the 204 observations.

- ^ Economic Sanctions Reconsidered, 3rd Edition, Hufbauer et al. p. 159

- ^

Pape, Robert A (Summer 1998). "Why Economic Sanctions Still Do Not Work". International Security. 23 (1): 66–77. doi:10.1162/isec.23.1.66. JSTOR 2539263. S2CID 57565095.

I examined the 40 claimed successes and found that only 5 stand up. Eighteen were actually settled by either direct or indirect use of force; in 8 cases there is no evidence that the target state made the demanded concessions; 6 do not qualify as instances of economic sanctions, and 3 are indeterminate. If I am right, then sanctions have succeeded in only 5 of 115 attempts, and thus there is no sound basis for even qualified optimism about the effects of sanctions.

- ^ A Strategic Understanding of UN Economic Sanctions: International Relations, Law, and Development, Golnoosh Hakimdavar, p. 105

- ^ Jump up to: a b Neuenkirch, Matthias; Neumeier, Florian (2015-12-01). "The impact of UN and US economic sanctions on GDP growth" (PDF). European Journal of Political Economy. 40: 110–125. doi:10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2015.09.001. ISSN 0176-2680.

- ^ Griswold, Daniel (2000-11-27). "Going Alone on Economic Sanctions Hurts U.S. More than Foes". Cato.org. Archived from the original on 2011-09-23. Retrieved 2015-03-30.

- ^ Capdevila, Gustavo (18 August 2000). "United Nations: US Riled by Economic Sanctions Report". Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ^ Marcus, Jonathan (26 July 2010). "Analysis: Do economic sanctions work?". BBC News. Retrieved 2015-03-30.

- ^ Peksen, Dursun; Jeong, Jin Mun (30 August 2017). "Domestic Institutional Constraints, Veto Players, and Sanction Effectiveness". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 63: 194–217. doi:10.1177/0022002717728105. S2CID 158050636 – via Sage Journals.

- ^ Peksen, Dursen (2009). ""Better or Worse?": The Effect of Economic Sanctions on Human Rights."". Journal of Peace Research. 46: 59–77. doi:10.1177/0022343308098404. S2CID 110505923.

- ^ Habibzadeh, Farrokh (September 2018). "Economic sanction: a weapon of mass destruction". The Lancet. 392 (10150): 816–817. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31944-5. PMID 30139528.

- ^ Mueller, John; Mueller, Karl (1999). "Sanctions of Mass Destruction". Foreign Affairs. 78 (3): 43–53. doi:10.2307/20049279. JSTOR 20049279.

- ^ [3] Archived February 27, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hans Köchler (ed.), Economic Sanctions and Development. Vienna: International Progress Organization, 1997. ISBN 3-900704-17-1

- ^ Gordon, Joy (1999-04-04). "Sanctions as siege warfare". The Nation. 268 (11): 18–22. ISSN 0027-8378.

- ^ Vengeyi, Obvious (2015). "Sanctions against Zimbabwe: A Comparison with Ancient Near Eastern Sieges". Journal of Gleanings from Academic Outliers. 4 (1): 69–87.

- ^ "Avalon Project - The Covenant of the League of Nations". avalon.law.yale.edu. Retrieved 2020-08-21.

- ^ "Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, The Paris Peace Conference, 1919, Volume XIII - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved 2020-08-21.

- ^ Lutfallah, Manji; Cortright, David (1998). "Sanctions: An Instrument of U.S Foreign Policy". Pakistan Horizon. 51: 29–35.

- ^ "Do I need an export licence?". GOV.UK. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

- ^ "SAP Help Portal". help.sap.com. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

- ^ "US Trade Sanctions Are a Trap for the Unwary | Norton Rose Fulbright". www.projectfinance.law. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

- ^ "Office of Foreign Assets Control - Sanctions Programs and Information | U.S. Department of the Treasury". home.treasury.gov. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

- ^ "Perform Sanction, PEPs and Watchlist Verification w/ Lexis Diligence". www.lexisnexis.com. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

- ^ "SAP Help Portal". help.sap.com. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

- ^ "World-Check KYC Screening & Due Diligence". www.refinitiv.com. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

- ^ "Export Control and Sanctions Compliance | About SAP". SAP. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

- ^ "Embargo Check". AnaSys a Bottomline Company. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

- ^ "Embargo Check". Uniserv GmbH - Customer Data Experts. 2021-01-22. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

- ^ University of Houston (2013). "The Embargo of 1807". digitalhistory.uh.edu.

- ^ Aaron Snyder; Jeffrey Herbener (December 15, 2004). "The Embargo of 1807 Grove City College Grove City, Pennsylvania" (PDF). gcc.edu. Grove City College. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-17.

- ^ "Embargo of 1807". monticello.org. April 8, 2013.

- ^ National Archives and Records Administration (15 August 2016). "Proclamation 3447--Embargo on all trade with Cuba". archives.gov.

- ^ Elizabeth Flock (February 7, 2012). "Cuba trade embargo turns 50: Still no rum or cigars, though some freedom in travel". washingtonpost.com.

- ^ Eric Weiner (October 15, 2007). "Officially Sanctioned: A Guide to the U.S. Blacklist". npr.org.

- ^ Daniel Hanson; Dayne Batten; Harrison Ealey (January 16, 2013). "It's Time For The U.S. To End Its Senseless Embargo Of Cuba". forbes.com.

- ^ Uri Friedman (September 13, 2011). "Obama Quietly Renews U.S. Embargo on Cuba". The Atlantic.

- ^ A., Conley, Heather (2016). The Kremlin Playbook: Understanding Russian influence in Central and Eastern Europe : a report of the CSIS Europe Program and the CSD Economics Program. Mina, James, Stefanov, Ruslan, Vladimirov, Martin, Center for Strategic and International Studies (Washington, D.C.), Center for the Study of Democracy (Bulgaria). Washington, DC. ISBN 9781442279582. OCLC 969727837.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Newnham, Randall (July 2013). "Pipeline Politics: Russian Energy Sanctions and the 2010 Ukrainian Elections". Journal of Eurasian Studies. 4 (2): 115–122. doi:10.1016/j.euras.2013.03.001.

- ^ "Russia-Ukraine 'Gas War' Damages Both Economies - Worldpress.org". www.worldpress.org. Retrieved 2017-10-27.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Newnham, Randall E. (2015). "Georgia on my mind? Russian sanctions and the end of the 'Rose Revolution'". Journal of Eurasian Studies. 6 (2): 161–170. doi:10.1016/j.euras.2015.03.008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Section, United Nations News Service (2016-05-04). "UN News - UN sanctions: what they are, how they work, and who uses them". UN News Service Section. Retrieved 2017-10-27.

- ^ Section, United Nations News Service (2011-03-14). "UN News - New UN project uses financial incentives to try to save the dugong". UN News Service Section. Retrieved 2017-10-27.

- ^ "Security Council Committee pursuant to resolutions 751 (1992) and 1907 (2009) concerning Somalia and Eritrea". www.un.org. Retrieved 2017-10-27.

- ^ "North Korea | Countries". www.nti.org. Retrieved 2017-10-27.

- ^ "Security Council Imposes Fresh Sanctions on Democratic People's Republic of Korea, Unanimously Adopting Resolution 2270 (2016) | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases". www.un.org. Retrieved 2017-10-27.

- ^ "Why Did Sanctions Fail Against North Korea?". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 2017-10-27.

- ^ "UN Arms embargo on Libya". www.sipri.org. Retrieved 2017-12-06.

- ^ "Evaluating the Impacts and Effectiveness of Targeted Sanctions". webcache.googleusercontent.com. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ^ UNICEF. "webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:Cw9j0nFWr-8J:www.unicefinemergencies.com/downloads/eresource/docs/Sanctions/2011-06-21%2520Literature%2520Review%2520on%2520the%2520Effects%2520of%2520Targeted%2520Sanctions.docx+&cd=5&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us&client=safari". webcache.googleusercontent.com. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ^ "Oil Embargo against Apartheid South Africa on richardknight.com".

- ^ Murphy, Caryle (1979-04-27). "To Cope With Embargoes, S. Africa Converts Coal Into Oil". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2020-12-12.

- ^ "Continental System Napoleon British Embargo Napoleon's 1812". Archived from the original on 2011-07-10.

- ^

"Pearl Harbor Raid, 7 December 1941". Washington: Department of the Navy -- Naval Historical Center. 3 December 2000. Archived from the original on 6 December 2000. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

The 7 December 1941 Japanese raid on Pearl Harbor was one of the great defining moments in history. A single carefully-planned and well-executed stroke removed the United States Navy's battleship force as a possible threat to the Japanese Empire's southward expansion. [...] The Japanese military, deeply engaged in the seemingly endless war it had started against China in mid-1937, badly needed oil and other raw materials. Commercial access to these was gradually curtailed as the conquests continued. In July 1941 the Western powers effectively halted trade with Japan. From then on, as the desperate Japanese schemed to seize the oil and mineral-rich East Indies and Southeast Asia, a Pacific war was virtually inevitable.

- ^ Maugeri, Leonardo (2006). The Age of Oil. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 112–116. ISBN 9780275990084.

- ^ "Energy Crisis (1970s)". The History Channel. 2010.

- ^ Leo Cendrowicz (February 10, 2010). "Should Europe Lift Its Arms Embargo on China?". Time. Archived from the original on February 13, 2010.

- ^ "Russia announces 'full embargo' on most food from US, EU". Deutsche Welle. 7 August 2014.

- ^ "Russia expands food imports embargo to non-EU states". English Radio. 13 August 2015. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ^ "Russia expands food import ban". BBC News. 2015-08-13. Retrieved 2018-06-17.

- ^ "Australia bans all live cattle exports to Indonesia". BBC News. 8 June 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ^ United States Department of the Treasury. "What You Need To Know About U.S. Economic Sanctions" (PDF). treasury.gov.

- ^ Josh Levs (January 23, 2012). "A summary of sanctions against Iran". cnn.com.

- ^ Wroughton, Lesley (22 April 2019). "U.S. to end all waivers on imports of Iranian oil, crude price jumps". Reuters.

- ^ "Iran oil: US to end sanctions exemptions for major importers". BBC News. 22 April 2019.

- ^ Howse, Robert L. and Genser, Jared M. (2008) "Are EU Trade Oh hell no on Burma Compatible with WTO Law?" Archived June 7, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Michigan Journal of International Law 29(2): pp. 165–96

- ^ "Clinton Ends Most N. Korea Sanctions". Globalpolicy.org. 1999-09-18. Retrieved 2015-03-30.

- ^ [4] Archived July 23, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea)". Department for Business Innovation and Skills. Archived from the original on 9 June 2009. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ "Senate overwhelmingly passes new Russia and Iran sanctions". The Washington Post. 15 June 2017.

- ^ Editorial, Reuters (2 August 2017). "Iran says new U.S. sanctions violate nuclear deal, vows 'proportional reaction'". Reuters.

- ^ "Syria sanctions". BBC News. 27 November 2011.

- ^ Rhodan, Maya (9 March 2015). "White House sanctions seven officials in Venezuela". Time. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- ^ "U.S. declares Venezuela a national security threat, sanctions top officials". Reuters. 10 March 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- ^ "President Trump Approves New Sanctions On Venezuela".

- ^ Emmott, Robin (13 November 2017). "EU readies sanctions on Venezuela, approves arms embargo". Reuters.

- ^ "Canada imposes sanctions on key Venezuelan officials". CBC Canada. Thomson Reuters. 22 September 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ Zilio, Michelle (22 September 2017). "Canada sanctions 40 Venezuelans with links to political, economic crisis". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 3 April 2019. Also at Punto de Corte and El Nacional

- ^ "Canada to impose sanctions on more Venezuelan officials". VOA News. Reuters. 30 May 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ "México rechaza elecciones en Venezuela y sanciona a siete funcionarios". Sumarium group (in Spanish). Retrieved 21 April 2018.[permanent dead link] Also at VPITV

- ^ Camacho, Carlos (27 March 2018). "Panama sanctions Venezuela, including Maduro & 1st Lady family companies". Latin American Herald Tribune. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ "Swiss impose sanctions on seven senior Venezuelan officials". Reuters. 28 March 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2019. Also at Diario Las Americas

- ^ "Sanctions: U.S. action on cyber crime" (PDF). pwc. PwC Financial Services Regulatory Practice, April, 2015.

- ^ Thompson, Natalie (2020-10-01). "Countering Malicious Cyber Activity: Targeted Financial Sanctions". SSRN 3770816. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Bennett, Cory (29 March 2016). "Obama extends cyber sanctions power".

- ^ "Brazil slaps trade sanctions on U.S. to retaliate for subsidies to cotton farmers". Content.usatoday.com. 2010-03-09. Retrieved 2015-03-30.

- ^ "EU sanctions Russians over rights abuses in Chechnya". Reuters. 22 March 2021.

- ^ Cockburn, Patrick (February 4, 1994). "US finally ends Vietnam embargo". The Independent. London.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pakistan and India UK nuclear exports restrictions Archived 2010-02-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lydia Polgreen (April 2, 2012). "Mali Coup Leaders Suffer Sanctions and Loss of Timbuktu". nytimes.com.

- ^ Callimachi, Rukmini (3 April 2012) "Post-coup Mali hit with sanctions by African neighbours". Globe and Mail. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ "Kosovo imposes embargo on Serbia". The Sofia Echo. 21 July 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- ^ "Georgia Doubles Wine Exports as Russian Market Reopens". RIA Novosti. 16 December 2013.

- ^ "Global Sanctions Database - GSDB". www.globalsanctionsdatabase.com. Retrieved 2021-05-18.

- ^ Felbermayr, Gabriel; Kirilakha, Aleksandra; Syropoulos, Constantinos; Yalcin, Erdal; Yotov, Yoto (2021-05-18). "The 'Global Sanctions Data Base': Mapping international sanction policies from 1950-2019". VoxEU.org. Retrieved 2021-05-18.

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Economic sanctions |

| Look up embargo in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- International sanctions

- Non-tariff barriers to trade

- Embargoes