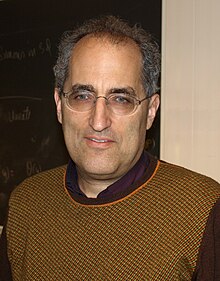

Edward Witten

Edward Witten (born August 26, 1951) is an American mathematical and theoretical physicist. He is currently the Charles Simonyi Professor in the School of Natural Sciences at the Institute for Advanced Study.[4] Witten is a researcher in string theory, quantum gravity, supersymmetric quantum field theories, and other areas of mathematical physics. In addition to his contributions to physics, Witten's work has significantly impacted pure mathematics.[5] In 1990, he became the first physicist to be awarded a Fields Medal by the International Mathematical Union, awarded for his 1981 proof of the positive energy theorem in general relativity.[6] He is considered to be the practical founder of M-theory.[7]

Early life and education[]

Witten was born on August 26, 1951, in Baltimore, Maryland, to a Jewish family.[8] He is the son of Lorraine (née Wollach) Witten and Louis Witten, a theoretical physicist specializing in gravitation and general relativity.[9]

Witten attended the Park School of Baltimore (class of '68), and received his Bachelor of Arts degree with a major in history and minor in linguistics from Brandeis University in 1971.[10]

He had aspirations in journalism and politics and published articles in both The New Republic and The Nation in the late 1960s.[11][12] In 1972 he worked for six months in George McGovern's presidential campaign.[when?][13]

Witten attended the University of Wisconsin–Madison for one semester as an economics graduate student before dropping out.[2] He returned to academia, enrolling in applied mathematics at Princeton University in 1973, then shifting departments and receiving a Ph.D. in physics in 1976 and completing a dissertation titled "Some problems in the short distance analysis of gauge theories" under the supervision of David Gross.[14] He held a fellowship at Harvard University (1976–77), visited Oxford University (1977–78),[3][15] was a junior fellow in the Harvard Society of Fellows (1977–1980), and held a MacArthur Foundation fellowship (1982).[4]

Research[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2021) |

Fields medal work[]

Witten was awarded the Fields Medal by the International Mathematical Union in 1990, becoming the first physicist to win the prize.[16]

In a written address to the ICM, Michael Atiyah said of Witten:[5]

"Although he is definitely a physicist (as his list of publications clearly shows) his command of mathematics is rivaled by few mathematicians, and his ability to interpret physical ideas in mathematical form is quite unique. Time and again he has surprised the mathematical community by a brilliant application of physical insight leading to new and deep mathematical theorems... He has made a profound impact on contemporary mathematics. In his hands physics is once again providing a rich source of inspiration and insight in mathematics."[5]

As an example of Witten's work in pure mathematics, Atiyah cites his application of techniques from quantum field theory to the mathematical subject of low-dimensional topology. In the late 1980s, Witten coined the term topological quantum field theory for a certain type of physical theory in which the expectation values of observable quantities encode information about the topology of spacetime.[17] In particular, Witten realized that a physical theory now called Chern–Simons theory could provide a framework for understanding the mathematical theory of knots and 3-manifolds.[18] Although Witten's work was based on the mathematically ill-defined notion of a Feynman path integral and was therefore not mathematically rigorous, mathematicians were able to systematically develop Witten's ideas, leading to the theory of Reshetikhin–Turaev invariants.[19]

Another result for which Witten was awarded the Fields Medal was his proof in 1981 of the positive energy theorem in general relativity.[20] This theorem asserts that (under appropriate assumptions) the total energy of a gravitating system is always positive and can be zero only if the geometry of spacetime is that of flat Minkowski space. It establishes Minkowski space as a stable ground state of the gravitational field. While the original proof of this result due to Richard Schoen and Shing-Tung Yau used variational methods,[21][22] Witten's proof used ideas from supergravity theory to simplify the argument.[citation needed]

A third area mentioned in Atiyah's address is Witten's work relating supersymmetry and Morse theory,[23] a branch of mathematics that studies the topology of manifolds using the concept of a differentiable function. Witten's work gave a physical proof of a classical result, the Morse inequalities, by interpreting the theory in terms of supersymmetric quantum mechanics.[citation needed]

M-theory[]

By the mid 1990s, physicists working on string theory had developed five different consistent versions of the theory. These versions are known as type I, type IIA, type IIB, and the two flavors of heterotic string theory (SO(32) and E8×E8). The thinking was that out of these five candidate theories, only one was the actual correct theory of everything, and that theory was the one whose low-energy limit matched the physics observed in our world today.[citation needed]

Speaking at the string theory conference at University of Southern California in 1995, Witten made the surprising suggestion that these five string theories were in fact not distinct theories, but different limits of a single theory which he called M-theory.[24][25] Witten's proposal was based on the observation that the five string theories can be mapped to one another by certain rules called dualities and are identified by these dualities. Witten's announcement led to a flurry of work now known as the second superstring revolution.[citation needed]

Other work[]

Another of Witten's contributions to physics was to the result of gauge/gravity duality. In 1997, Juan Maldacena formulated a result known as the AdS/CFT correspondence, which establishes a relationship between certain quantum field theories and theories of quantum gravity.[26] Maldacena's discovery has dominated high energy theoretical physics for the past 15 years because of its applications to theoretical problems in quantum gravity and quantum field theory. Witten's foundational work following Maldacena's result has shed light on this relationship.[27]

In collaboration with Nathan Seiberg, Witten established several powerful results in quantum field theories. In their paper on string theory and noncommutative geometry, Seiberg and Witten studied certain noncommutative quantum field theories that arise as limits of string theory.[28] In another well-known paper, they studied aspects of supersymmetric gauge theory.[29] The latter paper, combined with Witten's earlier work on topological quantum field theory,[17] led to developments in the topology of smooth 4-manifolds, in particular the notion of Seiberg–Witten invariants.[citation needed]

With Anton Kapustin, Witten has made deep mathematical connections between S-duality of gauge theories and the geometric Langlands correspondence.[30] Partly in collaboration with Seiberg, one of his recent interests include aspects of field theoretical description of topological phases in condensed matter and non-supersymmetric dualities in field theories that, among other things, are of high relevance in condensed matter theory. From a generalization of SYK models from condensed matter and quantum chaos, he has also recently[when?] brought tensor models of Gurau to the relevance of holographic and quantum gravity theories.[citation needed]

Witten has published influential and insightful work in many aspects of quantum field theories and mathematical physics, including the physics and mathematics of anomalies, integrability, dualities, localization, and homologies. Many of his results have deeply influenced areas in theoretical physics (often well beyond the original context of his results), including string theory, quantum gravity and topological condensed matter.[citation needed]

Awards and honors[]

Witten has been honored with numerous awards including a MacArthur Grant (1982), the Fields Medal (1990), the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement (1997),[31] the Nemmers Prize in Mathematics (2000), the National Medal of Science[32] (2002), Pythagoras Award[33] (2005), the Henri Poincaré Prize (2006), the Crafoord Prize (2008), the Lorentz Medal (2010) the Isaac Newton Medal (2010) and the Fundamental Physics Prize (2012). Since 1999, he has been a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (London), and in March 2016 was elected an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.[34][35] Pope Benedict XVI appointed Witten as a member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences (2006). He also appeared in the list of TIME magazine's 100 most influential people of 2004. In 2012 he became a fellow of the American Mathematical Society.[36] Witten was elected as a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1984 and a member of the National Academy of Sciences in 1988.[37][38]

In an informal poll at a 1990 cosmology conference, Witten received the largest number of mentions as "the smartest living physicist".[39]

Personal life[]

Witten has been married to Chiara Nappi, a professor of physics at Princeton University, since 1979.[40] They have two daughters and one son. Their daughter Ilana B. Witten is a neuroscientist at Princeton University,[41] and daughter Daniela Witten is a biostatistician at the University of Washington.[42]

Witten sits on the board of directors of Americans for Peace Now and on the advisory council of J Street.[43] He supports the two-state solution and advocates a boycott of Israeli institutions and economic activity beyond its 1967 borders, though not of Israel itself.[44]

Selected publications[]

- Some Problems in the Short Distance Analysis of Gauge Theories. Princeton University, 1976. (Dissertation.)

- Roman Jackiw, David Gross, Sam B. Treiman, Edward Witten, Bruno Zumino. Current Algebra and Anomalies: A Set of Lecture Notes and Papers. World Scientific, 1985.

- Green, M., John H. Schwarz, and E. Witten. Superstring Theory. Vol. 1, Introduction. Cambridge Monographs on Mathematical Physics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1988. ISBN 978-0-521-35752-4.

- Green, M., John H. Schwarz, and E. Witten. Superstring Theory. Vol. 2, Loop Amplitudes, Anomalies and Phenomenology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1988. ISBN 978-0-521-35753-1.

- Quantum fields and strings: a course for mathematicians. Vols. 1, 2. Material from the Special Year on Quantum Field Theory held at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, NJ, 1996–1997. Edited by Pierre Deligne, Pavel Etingof, Daniel S. Freed, Lisa C. Jeffrey, David Kazhdan, John W. Morgan, David R. Morrison and Edward Witten. American Mathematical Society, Providence, RI; Institute for Advanced Study (IAS), Princeton, NJ, 1999. Vol. 1: xxii+723 pp.; Vol. 2: pp. i–xxiv and 727–1501. ISBN 0-8218-1198-3, 81–06 (81T30 81Txx).

References[]

- ^ "Announcement of 2016 Winners". World Cultural Council. June 6, 2016. Archived from the original on June 7, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Woit, Peter (2006). Not Even Wrong: The Failure of String Theory and the Search for Unity in Physical Law. New York: Basic Books. p. 105. ISBN 0-465-09275-6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Edward Witten – Adventures in physics and math (Kyoto Prize lecture 2014)

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Edward Witten". Institute for Advanced Study. 9 December 2019. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Atiyah, Michael (1990). "On the Work of Edward Witten" (PDF). Proceedings of the International Congress of Mathematicians. pp. 31–35. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 1, 2017.

- ^ Michael Atiyah. "On the Work of Edward Witten" (PDF). Mathunion.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ Duff 1998, p. 65

- ^ Witten biography - MacTutor History of Mathematics

- ^ The International Who's Who 1992-93, p. 1754.

- ^ "Edward Witten (1951)". www.nsf.gov. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- ^ Witten, Edward. "Are You Listening, D.H. Lawrence?, by Edward Witten, THE NEW REPUBLIC". The Unz Review. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- ^ Witten, Edward. "The New Left, by Edward Witten, THE NATION". The Unz Review. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- ^ Farmelo, Graham (May 2, 2019). "'The Universe Speaks in Numbers' – Interview 5". Graham Farmelo. Archived from the original on May 3, 2019. Retrieved August 25, 2020. Alt URL

- ^ Witten, E. (1976). Some problems in the short distance analysis of gauge theories.

- ^ Interview by Hirosi Ooguri, Notices Amer. Math. Soc., May 2015, pp. 491–506.

- ^ "Edward Witten" (PDF). 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 4, 2012. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Witten, Edward (1988), "Topological quantum field theory", Communications in Mathematical Physics, 117 (3): 353–386, Bibcode:1988CMaPh.117..353W, doi:10.1007/BF01223371, S2CID 43230714

- ^ Witten, Edward (1989). "Quantum Field Theory and the Jones Polynomial" (PDF). Communications in Mathematical Physics. 121 (3): 351–399. Bibcode:1989CMaPh.121..351W. doi:10.1007/BF01217730. S2CID 14951363.

- ^ Reshetikhin, Nicolai; Turaev, Vladimir (1991). "Invariants of 3-manifolds via link polynomials and quantum groups". Inventiones Mathematicae. 103 (1): 547–597. Bibcode:1991InMat.103..547R. doi:10.1007/BF01239527. S2CID 123376541.

- ^ Witten, Edward (1981). "A new proof of the positive energy theorem". Communications in Mathematical Physics. 80 (3): 381–402. Bibcode:1981CMaPh..80..381W. doi:10.1007/BF01208277. S2CID 1035111.

- ^ Schoen, Robert; Yau, Shing-Tung (1979). "On the proof of the positive mass conjecture in general relativity". Communications in Mathematical Physics. 65 (1): 45. Bibcode:1979CMaPh..65...45S. doi:10.1007/BF01940959. S2CID 54217085.

- ^ Schoen, Robert; Yau, Shing-Tung (1981). "Proof of the positive mass theorem. II". Communications in Mathematical Physics. 79 (2): 231. Bibcode:1981CMaPh..79..231S. doi:10.1007/BF01942062. S2CID 59473203.

- ^ Witten, Edward (1982). "Super-symmetry and Morse Theory". Journal of Differential Geometry. 17 (4): 661–692. doi:10.4310/jdg/1214437492.

- ^ University of Southern California, Los Angeles, Future Perspectives in String Theory, March 13–18, 1995, E. Witten: Some problems of strong and weak coupling

- ^ Witten, Edward (1995). "String theory dynamics in various dimensions". Nuclear Physics B. 443 (1): 85–126. arXiv:hep-th/9503124. Bibcode:1995NuPhB.443...85W. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(95)00158-O. S2CID 16790997.

- ^ Juan M. Maldacena (1998). "The Large N limit of superconformal field theories and supergravity". Advances in Theoretical and Mathematical Physics. 2 (2): 231–252. arXiv:hep-th/9711200. Bibcode:1998AdTMP...2..231M. doi:10.4310/ATMP.1998.V2.N2.A1.

- ^ Edward Witten (1998). "Anti-de Sitter space and holography". Advances in Theoretical and Mathematical Physics. 2 (2): 253–291. arXiv:hep-th/9802150. Bibcode:1998AdTMP...2..253W. doi:10.4310/ATMP.1998.v2.n2.a2. S2CID 10882387.

- ^ Seiberg, Nathan; Witten, Edward (1999). "String Theory and Noncommutative Geometry". Journal of High Energy Physics. 1999 (9): 032. arXiv:hep-th/9908142. Bibcode:1999JHEP...09..032S. doi:10.1088/1126-6708/1999/09/032. S2CID 668885.

- ^ Seiberg, Nathan; Witten, Edward (1994). "Electric-magnetic duality, monopole condensation, and confinement in N=2 supersymmetric Yang-Mills theory". Nuclear Physics B. 426 (1): 19–52. arXiv:hep-th/9407087. Bibcode:1994NuPhB.426...19S. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(94)90124-4. S2CID 14361074.

- ^ Kapustin, Anton; Witten, Edward (April 21, 2006). "Electric-Magnetic Duality And The Geometric Langlands Program". Communications in Number Theory and Physics. 1: 1–236. arXiv:hep-th/0604151. Bibcode:2007CNTP....1....1K. doi:10.4310/CNTP.2007.v1.n1.a1. S2CID 30505126.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ "Edward Witten", The President's National Medal of Science: Recipient Details.

- ^ "Il premio Pitagora al fisico teorico Witten". Il Crotonese (in Italian). September 23, 2005. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011.

- ^ "Foreign Members", The Royal Society.

- ^ "Fellows". June 21, 2016.

- ^ List of Fellows of the American Mathematical Society, retrieved September 1, 2013.

- ^ "Edward Witten". American Academy of Arts & Sciences. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ "Edward Witten". www.nasonline.org. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ Lemonick, Michael (April 26, 2004). "Edward Witten". Time. Archived from the original on September 1, 2006. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

"At a 1990 conference on cosmology," wrote John Horgan in 2014, "I asked attendees, who included folks like Stephen Hawking, Michael Turner, James Peebles, Alan Guth and Andrei Linde, to nominate the smartest living physicist. Edward Witten got the most votes (with Steven Weinberg the runner-up). Some considered Witten to be in the same league as Einstein and Newton." See "Physics Titan Edward Witten Still Thinks String Theory 'on the Right Track'". scientificamerican.com. September 22, 2014. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- ^ Witten, Ed. "The 2014 Kyoto Prize Commemorative Lecture in Basic Sciences" (PDF). Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "Faculty » Ilana B. Witten". princeton.edu. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "UW Faculty » Daniela M. Witten". washington.edu. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ "Advisory Council". J Street. 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ^ "For an Economic Boycott and Political Nonrecognition of the Israeli Settlements in the Occupied Territories", NYRB, October 2016.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edward Witten. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Edward Witten |

| Scholia has an author profile for Edward Witten. |

- Faculty webpage

- Publications on ArXiv

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Edward Witten", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews

- Edward Witten at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- A Physicist's Physicist Ponders the Nature of Reality, Interview with Nathalie Wolchover in Quanta Magazine, November 28, 2017

- 1951 births

- 20th-century American physicists

- 21st-century American physicists

- Albert Einstein Medal recipients

- Albert Einstein World Award of Science Laureates

- Brandeis University alumni

- Clay Research Award recipients

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Fellows of the American Mathematical Society

- Fellows of the American Physical Society

- Fields Medalists

- Foreign Members of the Royal Society

- Harvard Fellows

- Institute for Advanced Study faculty

- Highly Cited Researchers

- Jewish American scientists

- Jewish physicists

- Kyoto laureates in Basic Sciences

- Living people

- MacArthur Fellows

- Mathematical physicists

- Members of the American Philosophical Society

- Members of the French Academy of Sciences

- Members of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences

- Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences

- National Medal of Science laureates

- Lorentz Medal winners

- Park School of Baltimore alumni

- Princeton University alumni

- Princeton University faculty

- Scientists from Baltimore

- American string theorists

- Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh