Faith Ringgold

Faith Ringgold | |

|---|---|

Faith Ringgold in April 2017 at the Brooklyn Museum | |

| Born | Faith Willi Jones October 8, 1930 |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | City College of New York |

| Known for | Painting Textile arts Children's Books |

Notable work | See publications and notable work in collections. |

| Movement | Feminist art movement, Civil rights |

| Awards | 2009 Peace Corps Award |

Faith Ringgold[1] (born October 8, 1930 in Harlem,[2] New York City) is an American painter, writer, mixed media sculptor, and performance artist, best known for her narrative quilts.

Early life[]

Faith Ringgold was born the youngest of three children on October 8, 1930, in Harlem Hospital, New York City.[3]:24 Her parents, Andrew Louis Jones and Willi Posey Jones, were descendants of working-class families displaced by the Great Migration. Ringgold's mother was a fashion designer and her father, as well as working a range of jobs, was an avid storyteller.[4] They raised her in an environment that encouraged her creativity. After the Harlem Renaissance, Ringgold's childhood home in Harlem became surrounded by a thriving arts scene – where figures such as Duke Ellington and Langston Hughes lived just around the corner.[3]:27 Her childhood friend, Sonny Rollins, who would grow up to be a prominent jazz musician, often visited her family and practiced saxophone at their parties.[3]:28 Because of her chronic asthma, Ringgold explored visual art as a major pastime through the support of her mother, often experimenting with crayons as a young girl.[3]:24 She also learned how to sew and work creatively with fabric from her mother.[5] Ringgold maintains that despite her upbringing in Great Depression-era Harlem, 'this did not mean [she] was poor and oppressed' – she was 'protected from oppression and surrounded by a loving family.'[3]:24 With all of these influences combined, Ringgold's future artwork was greatly affected by the people, poetry, and music she experienced in her childhood, as well as the racism, sexism, and segregation she dealt with in her everyday life.[3]:9

In 1950, due to pressure from her family, Ringgold enrolled at the City College of New York to major in art, but was forced to major in art education instead, as City College only allowed women to be enrolled in certain majors.[6][7]:134 The same year, she also married a jazz pianist named Robert Earl Wallace and had two children, Michele and Barbara Faith Wallace. Ringgold and Wallace separated four years later due to his heroin addiction.[8]:54 In the meantime, she studied with artists Robert Gwathmey and Yasuo Kuniyoshi. She was also introduced to printmaker Robert Blackburn, with whom she would collaborate on a series of prints 30 years later.[3]:29

In 1955, Ringgold received her bachelor's degree from City College and soon afterward taught in the New York City public school system.[9] In 1959, she received her master's degree from City College and left with her mother and daughters on her first trip to Europe.[9] While travelling abroad in Paris, Florence, and Rome, Ringgold visited many museums, including the Louvre. This museum in particular inspired her future series of quilt paintings known as the French Collection. This trip was abruptly cut short, however, due to the untimely death of her brother in 1961. Faith Ringgold, her mother, and her daughters all returned to the US for his funeral.[8]:141 She married Burdette Ringgold on May 19, 1962.[9]

Ringgold visited West Africa twice: once in 1976 and again in 1977. These travels would deeply influence her mask making, doll painting and sculptures.

Artwork[]

Faith Ringgold's artistic practice is extremely varied – from painting to quilts, from sculptures and performance art to children's books. As an educator, she taught in both the New York City Public school system and at college level. In 1973, she quit teaching public school to devote herself to creating art full-time.

Painting[]

Ringgold began her painting career in the 1950s after receiving her degree.[9] Her early work is composed with flat figures and shapes. She was inspired by the writings of James Baldwin and Amiri Baraka, African art, Impressionism, and Cubism to create the works she made in the 1960s. Though she received a great deal of attention with these images, many of her early paintings focused on the underlying racism in everyday activities;[10] which made sales difficult, and disquieted galleries and collectors.[3]:41 These works were also politically based and reflected her experiences growing up during the Harlem Renaissance – themes which matured during the Civil Rights Movement and Women's movement.[11]:8

Taking inspiration from artist Jacob Lawrence and writer James Baldwin, Ringgold painted her first political collection named the American People Series in 1963, which portrays the American lifestyle in relation to the Civil Rights Movement. American People Series illustrates these racial interactions from a female point of view, and calls basic racial issues in America into question.[8]:145 In a 2019 article with Hyperallergic magazine, Ringgold explained that her choice for a political collection comes from the turbulent atmosphere around her: "( ... ) it was the 1960s and I could not act like everything was okay. I couldn't paint landscapes in the 1960s – there was too much going on. This is what inspired the American People Series."[12] This revelation stemmed from her work being rejected by Ruth White, a gallery owner in New York.[4] Oil paintings like For Members Only, Neighbors, Watching and Waiting, and The Civil Rights Triangle also embody these themes.

In 1972, as part of a commission sponsored by the Creative Artists Public Service Program, Ringgold installed For the Women's House[13] in the Women's Facility on Rikers Island. The large-scale mural is an anti-carceral work, composed of depictions of women in professional and civil servant roles, representing positive alternatives to incarceration. The women portrayed are inspired by extensive interviews Ringgold conducted with women inmates, and the design divides the portraits into triangular sections – referencing Kuba textiles of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It was her first public commission and widely regarded as her first feminist work.[14] Subsequently, the work inspired the creation of Art Without Walls, an organization that brings art to prisons.[4]

Around the opening of her show for American People, Ringgold also worked on her collection called America Black ( also called the Black Light Series, ) in which she experimented with darker colors. This was spurred by her observation that "white western art was focused around the color white and light/contrast/chiaroscuro, while African cultures, in general used darker colors and emphasized color rather than tonality to create contrast." This led her to pursue "a more affirmative black aesthetic".[8]:162–164 Her American People series concluded with larger-scale murals, such as The Flag Is Bleeding, U.S. Postage Stamp Commemorating the Advent of Black Power People, and Die. These murals lent her a fresher and stronger prospective to her future artwork.

Her piece, Flag for the Moon, was to be purchased by the Chase Manhattan Bank until the representatives that were sent to purchase a piece of Ringgold work realized the writing on the piece that made up the starts and stripes of the American Flag it depicted said "DIE N****R".[15] The representatives returned and purchased Black Light #9: American Spectrum.[15]

In the French Collection, a multi-paneled series that touches on the truths and mythologies of modernism, Ringgold explored a different solution to overcoming the painful historical legacy of women and men of African descent. As France was the home of modern art at the time, it also became the source for African-American artists to find their own "modern" identity.[11]:2

During the 1970's she also made a "Free Angela" poster design for the Black Panthers,[16] although it was never widely produced Ringgold has stated that she has given a copy of the design to Angela Davis herself.[17]

Quilts[]

Ringgold stated she switched from painting to fabric to get away from the association of painting with Western/European traditions.[18] Similarly, the use of quilt allowed her advocation of the feminist movement as she could simply roll up her quilts to take to the gallery, therefore negating the need of any assistance from her husband.[15]

In 1972 Ringgold travelled to Europe in the summer of 1972 with her daughter Michele. While Michele went to visit friends in Spain, Ringgold continued onto Germany and the Netherlands. In Amsterdam, she visited the Rijksmuseum, which became one of the most influential experiences affecting her mature work, and subsequently, lead to the development of her quilt paintings. In the museum, Ringgold encountered a collection of 14th- and 15th-century Nepali paintings, which inspired her to produce fabric borders around her own work.

When she returned to the US, a new painting series was born: The Slave Rape Series. In these works, Ringgold took the perspective of an African woman captured and sold into slavery. Her mother, Willi Posey, collaborated with her on this project, as Posey was a popular Harlem clothing designer and seamstress during the 1950s[19] and taught Ringgold how to quilt in the African-American tradition.[20] This collaboration eventually led to their first quilt, Echoes of Harlem, in 1980.[3]:44–45 Ringgold was also taught the art of quilting in an African-American style by her grandmother,[4] who had in turn learned it from her mother, Susie Shannon, who was a slave.[4]

Ringgold quilted her stories to be heard, since at the time no one would publish the autobiography she had been working on; making her work both autobiographical and artistic. In an interview with the Crocker Art Museum she stated, "In 1983, I began writing stories on my quilts as an alternative. That way, when my quilts were hung up to look at, or photographed for a book, people could still read my stories."[21] Her first quilt story Who's Afraid of Aunt Jemima? (1983) depicts the story of Aunt Jemima as a matriarch restaurateur and fictionally revises "the most maligned black female stereotype."[22] Another piece, titled Change: Faith Ringgold’s Over 100 Pounds Weight Loss Performance Story Quilt (1986), engages the topic of "a woman who wants to feel good about herself, struggling to [the] cultural norms of beauty, a person whose intelligence and political sensitivity allows her to see the inherent contradictions in her position, and someone who gets inspired to take the whole dilemma into an artwork".[11]:9

The series of story quilts from Ringgold's French Collection focuses on historical African-American women who dedicated themselves to change the world (The Sunflowers Quilting Bee at Arles). It also calls out and redirects of the male gaze, and illustrates the immersive power of historical fantasy and childlike imaginative storytelling. Many of her quilts went on to inspire the children books that she later made, such as Dinner at Aunt Connie's House (1993) published by Hyperion Books, based on The Dinner Quilt (1988).

Sculpture[]

In 1973, Ringgold began experimenting with sculpture as a new medium to document her local community and national events. Her sculptures range from costumed masks to hanging and freestanding soft sculptures, representing both real and fictional characters from her past and present. She began making mixed-media costumed masks after hearing her students express their surprise that she did not already include masks in her artistic practice.[8]:198 The masks were pieces of linen canvas that were painted, beaded and woven with raffia for hair, and rectangular pieces of cloth for dresses with painted gourds to represent breasts. She eventually made a series of eleven mask costumes, called the Witch Mask Series, in a second collaboration with her mother. These costumes could also be worn, but would lend the wearer female characteristics, such as breasts, bellies and hips. In her memoir , Ringgold also notes that in traditional African rituals, the mask wearers would be men, despite the mask's feminine features.[8]:200 In this series, however, she wanted the masks to have both a "spiritual and sculptural identity",[8]:199The dual purpose was important to her: the masks could be worn, and were not solely decorative.

After the Witch Mask Series, she moved onto another series of 31 masks, the Family of Woman Mask Series in 1973, which commemorated women and children whom she had known as a child. She later began making dolls with painted gourd heads and costumes (also made by her mother, which subsequently lead her to life-sized soft sculptures). The first of this series was her piece, Wilt, a 7'3" portrait sculpture of basketball player Wilt Chamberlain. She began with Wilt as a response to some negative comments that Chamberlain made on African-American women in his autobiography. Wilt features three figures, the basketball player with a white wife and a mixed daughter, both fictional characters. The sculptures had baked and painted coconuts shell heads, anatomically-correct foam and rubber bodies covered in clothing, and hung from the ceiling on invisible fishing lines. Her soft sculptures evolved even further into life sized "portrait masks", representing characters from her life and society, from unknown Harlem denizens to Martin Luther King Jr. She carved foam faces into likenesses that were then spray-painted—however, in her memoir she describes how the faces later began to deteriorate and had to be restored. She did this by covering the faces in cloth, molding them carefully to preserve the likeness.

Performance art[]

As many of Ringgold's mask sculptures could also be worn as costumes, her transition from mask-making to performance art was a self-described "natural progression".[8]:206 Though art performance pieces were abundant in the 1960s and '70s, Ringgold was instead inspired by the African tradition of combining storytelling, dance, music, costumes and masks into one production.[8]:238 Her first piece involving these masks was The Wake and Resurrection of the Bicentennial Negro. The work was a response to the American Bicentennial celebrations of 1976; a narrative of the dynamics of racism and the oppression of drug addiction. She voices the opinion of many other African Americans – there was "no reason to celebrate two hundred years of American Independence…for almost half of that time we had been in slavery".[8]:205 The piece was performed in mime with music and lasted thirty minutes, and incorporated many of her past paintings, sculptures and installations. She later moved on to produce many other performance pieces including a solo autobiographical performance piece called Being My Own Woman: An Autobiographical Masked Performance Piece, a masked story performance set during the Harlem Renaissance called The Bitter Nest (1985), and a piece to celebrate her weight loss called Change: Faith Ringgold’s Over 100 Pound Weight Loss Performance Story Quilt (1986). Each of these pieces were multidisciplinary, involving masks, costumes, quilts, paintings, storytelling, song and dance. Many of these performances were also interactive, as Ringgold encouraged her audience to sing and dance with her. She describes in her autobiography, We Flew Over the Bridge, that her performance pieces were not meant to shock, confuse or anger, but rather "simply another way to tell my story".[8]:238

Publications[]

Ringgold has written and illustrated 17 children's books.[23] Her first was Tar Beach, published by Crown in 1991, based on her quilt story of the same name.[24] For that work she won the Ezra Jack Keats New Writer Award[25] and the Coretta Scott King Award for Illustration.[26] She was also the runner-up for the Caldecott Medal, the premier American Library Association award for picture book illustration.[24] In her picture books, Ringgold approaches complex issues of racism in straightforward and hopeful ways, combining fantasy and realism to create an uplifting message for children.[27]

Activism[]

Ringgold has been an activist since the 1970s, participating in several feminist and anti-racist organizations. In 1968, fellow artist Poppy Johnson, and art critic Lucy Lippard, founded the Ad Hoc Women's Art Committee with Ringgold and protested a major modernist art exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Members of the committee demanded that women artists account for fifty percent of the exhibitors and created disturbances at the museum by singing, blowing whistles, chanting about their exclusion, and leaving raw eggs and sanitary napkins on the ground. Not only were women artists excluded from this show, but no African-American artists were represented either. Even Jacob Lawrence, an artist in the museum's permanent collection, was excluded.[3]:41 After participating in more protest activity, Ringgold was arrested on November 13, 1970.[3]:41

Ringgold and Lippard also worked together during their participation in the group Women Artists in Revolution (WAR). That same year, Ringgold and her daughter Michele Wallace founded Women Students and Artists for Black Art Liberation (WSABAL). Around 1974, Ringgold and Wallace were founding members of the National Black Feminist Organization. Ringgold was also a founding member of the "Where We At" Black Women Artists, a New York-based women's art collective associated with the Black Arts Movement. The inaugural show of "Where We At" featured soul food rather than traditional cocktails, exhibiting an embrace of cultural roots. The show was first presented in 1971 with eight artists and had expanded to 20 by 1976.[28]

In a statement about black representation in the arts, she said:

"When I was in elementary school I used to see reproductions of Horace Pippin’s 1942 painting called John Brown Going to His Hanging in my textbooks. I didn't know Pippin was a black person. No one ever told me that. I was much, much older before I found out that there was at least one black artist in my history books. Only one. Now that didn't help me. That wasn't good enough for me. How come I didn't have that source of power? It is important. That's why I am a black artist. It is exactly why I say who I am."[3]:62

In 1988, Ringgold co-founded the Coast-to-Coast National Women Artists of Color Projects with Clarissa Sligh.[29] From 1988 to 1996, this organization exhibited the works of African American women across the United States.[30] In 1990, Sligh was one of three organizers of the exhibit Coast to Coast: A Women of Color National Artists’ Book Project held January 14 – February 2, 1990, at the Flossie Martin Gallery, and later at the Eubie Blake Center and the Artemesia Gallery. Ringgold wrote the catalog introduction titled "History of Coast to Coast". More than 100 women artists of color were included. The catalog included brief artist statements and photos of the artists' books, including works by Sligh, Ringgold, Emma Amos, Beverly Buchanan, Elizabeth Catlett, Martha Jackson Jarvis, Howardena Pindell, Adrian Piper, Joyce Scott, and Deborah Willis.[31]

Later life[]

In 1987, Ringgold accepted a teaching position in the Visual Arts Department at the University of California, San Diego.[32] She continued to teach until 2002, when she retired.[33]

In 1995, Ringgold published her first autobiography titled We Flew Over the Bridge. The book is a memoir detailing her journey as an artist and life events, from her childhood in Harlem and Sugar Hill, to her marriages and children, to her professional career and accomplishments as an artist. Two years later she received two honorary doctorates, one for Education from Wheelock College in Boston, and the second for Philosophy from Molloy College in New York.[9]

She has now received over 80 awards and honors and 23 Honorary Doctorates[34]

She was interviewed for the film !Women Art Revolution.[35]

Ringgold resides with her second husband Burdette "Birdie" Ringgold, who she married in 1962,[4] in a home in Englewood, New Jersey, where she has lived and maintained a steady studio practice since 1992.[36]

Copyright suit against BET[]

Ringgold was the plaintiff in a significant copyright case, Ringgold v. Black Entertainment Television.[37] Black Entertainment Television (BET) had aired several episodes of the television series Roc in which a Ringgold poster was shown on nine occasions for a total of 26.75 seconds. Ringgold sued for copyright infringement. The court found BET liable, rejecting a de minimis defense raised by BET, which had argued that the use of Ringgold's copyrighted work was so minimal that it did not constitute an infringement.

In popular culture[]

- A new elementary and middle school in Hayward, California, Faith Ringgold School K-8, was named after her in 2007.

- Her name appears in the lyrics of the Le Tigre song "Hot Topic."[38]

Selected exhibitions[]

Her first one-woman show, American People opened December 19, 1967 at Spectrum Gallery.[39] The show included three of her murals: The Flag is Bleeding, U.S. Postage Stamp Commemorating the Advent of Black Power, and Die.[39] She wanted the opening to not be "another all white" opening but a "refined black art affair."[39] There was music and her children invited their classmates.[39] Over 500 people attended the opening including artists Romaire Bearden, Norman Lewis, and Richard Mayhew.[39]

In 2019 a major retrospective of Ringgold's work was mounted by London's Serpentine Galleries, to run from June 6 until September 8.[40]

Notable works in public collections[]

- Tar Beach (Part 1, No. 1 from the Women on a Bridge Series), 1998, The Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY

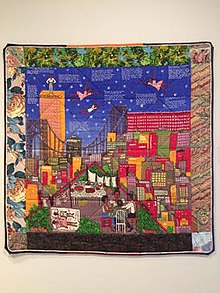

- Street Story Quilt, 1985, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

- Freedom of Speech, 1990, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

- American People Series #20: Die, 1967, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY

- Matisse's Model (Part 1, No. 5 from the French Collection), 1991, The Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, MD

- Tar Beach 2, 1990, The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA

- Picasso's Studio (Part 1, No. 7 from the French Collection), 1991, Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, MA

- Dream 2: King and the Sisterhood, 1988, Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Boston, MA

- Bitter Nest #1: Love in the School Yard, 1988, Phoenix Art Museum, Phoenix, AZ

- Bitter Nest #2: Harlem Renaissance Party, 1988, The National Museum of American Art, Washington DC

- Mama can sing, Papa can blow, The Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, CA

Publications[]

| Library resources about Faith Ringgold |

| By Faith Ringgold |

|---|

- Tar Beach, New York: Crown Publishing Company, 1991. ISBN 978-0-517-88544-4

- Aunt Harriet's Underground Railroad in the Sky, New York: Random House, Crown Publishers. ISBN 978-0-517-88543-7

- Dinner at Aunt Connie's House, New York: Hyperion Books for Children. ISBN 978-0-590-13713-3

- We Flew Over The Bridge: Memoirs of Faith Ringgold, Boston, Mass.: Little, Brown and Company, 1995; Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0-8223-3564-1

- Talking To Faith Ringgold, by Faith Ringgold, Linda Freeman and Nancy Roucher, New York: Crown Books for Young Readers, 1996. ISBN 978-0-517-70914-6

- 7 Passages to a Flight, an artist's book, San Diego, California: Brighton Press.

- Bonjour Lonnie, New York: Hyperion Books for Young Readers, 1996. ISBN 978-0-7868-0076-6

- My Dream of Martin Luther King, New York: Crown Books for Young Readers. ISBN 978-0-517-88577-2

- The Invisible Princess, New York: Crown Books for Young Readers. ISBN 978-0-440-41735-4

- If a Bus Could Talk, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999. ISBN 978-0-689-85676-1

- Counting to Tar Beach, New York: Crown, 2000. ISBN 978-0-517-80022-5

- Cassie's Colorful Day, New York: Crown, 2000. ISBN 978-0-517-80021-8

- Cassie's Word Quilt, New York: Crown, 2001. ISBN 978-0-553-11233-7

- O Holy Night: Christmas with the Boys Choir of Harlem, New York: Harper Collins, 2004. ISBN 978-1-4223-5512-1

- The Three Witches by Zora Neale Hurston, illustrated by Faith Ringgold, New York: Harper Collins, 2005. ISBN 978-0-06-000649-5

- Bronzeville Boys and Girls (poetry) by Gwendolyn Brooks illustrated by Faith Ringgold, New York: Harper Collins, 2007. ISBN 978-0-06-029505-9

- What Will You Do for Peace? Impact of 9/11 on New York City Youth, InterRelations Collaborative, Inc., 2004. ISBN 978-0-9761753-0-8

See also[]

- Feminist art movement in the United States

- Black feminism

- Harlem Renaissance

- Quilts

- Sculpture

- Painting

References[]

- ^ "Faith Ringgold's Website".

- ^ "Faith Ringgold". Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved May 1, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l Holton, Curlee Raven (2004). A View From the Studio. Boston: Bunker Hill Pub in association with the Allentown Art Museum. ISBN 978-1-593-73045-1. OCLC 59132090.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Faith Ringgold Biography, Life & Quotes". The Art Story. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ "Faith Ringgold". Biography. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- ^ "About: Our History". The City College of New York. June 30, 2015. Retrieved February 27, 2018.

- ^ Farrington, Lisa (2011). Creating Their Own Image: The History of African-American Women Artists. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-76760-1. OCLC 57005944.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k Ringgold, Faith (1995). We Flew Over the Bridge: The Memoirs of Faith Ringgold. Boston: Little Brown & Co. ISBN 978-0-821-22071-9. OCLC 607544394.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Ringgold, Faith. "Faith Ringgold Chronology" (PDF). Faith Ringgold. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 22, 2016. Retrieved September 12, 2015.

- ^ Wallace, Michelle (2010). American People, Black Light: Faith Ringgold's Paintings of the 1960s. New York: Neuberger Museum of Art. p. 31. ISBN 978-0979562938.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ringgold, Faith (1998). Dancing at the Louvre: Faith Ringgold's French Collection and Other Story Quilts. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21430-9. OCLC 246277942.

- ^ "AS-2007_10zL0075-300". Hyperallergic. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- ^ "Brooklyn Museum Tumblr Page".

- ^ Wallace, Michele (1990). Invisibility Blues: From Pop to Theory. London, New York: Verso. pp. 34–43. ISBN 978-1859844878.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "The quilts that made America quake: how Faith Ringgold fought the power with fabric". The Guardian. June 4, 2019. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ "Faith Ringgold". Biography. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ Haider, Arwa. "Faith Ringgold: The artist who captured the soul of the US". www.bbc.com. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ Barbara J., Bloemink (1999). re/righting history: counternarratives by contemporary african-american artists. Katonah Museum of Art. p. 16. ISBN 0-915171-51-1.

- ^ (2010). Adler, Ester (ed.). Modern Women; Women Artists at the Museum of Modern Art. New York: The Museum of Modern Art. p. 487. ISBN 9780870707711.

- ^ Millman, Joyce (December 2005). "Faith Ringgold's Quilts and Picturebooks: Comparisons and Contributions". Children's Literature in Education. 36 (4): 383. doi:10.1007/s10583-005-8318-0. S2CID 145804995.

- ^ ""Faith Ringgold: An American Artist" to Open February 2018". Crocker Art Museum. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- ^ Tucker, Marcia (1994). Bad Girls. New York: The MIT Press. p. 70.

- ^ Faith Ringgold blogspot.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Tar Beach" (one library record). WorldCat.

- ^ "Ezra Jack Keats Book Award Winners". ezra-jack-keats.org.

- ^ "Brooklyn Museum". Faith Ringgold. Retrieved October 18, 2011.

- ^ Millman, Joyce (December 2005). "Faith Ringgold's Quilts and Picturebooks: Comparisons and Contributions". Children's Literature in Education. 36 (4): 388. doi:10.1007/s10583-005-8318-0. S2CID 145804995.

- ^ Fax, Elton C. (1977). Black Artists of the New Generation. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company. pp. 176. ISBN 0-396-07434-0.

- ^ "Donor Spotlight: Clarissa Sligh". wsworkshop.org. March 26, 2009. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ^ Works by Women to go on Display in Wooster Toledo Blade, August 21, 1991.

- ^ Coast to coast: a Women of Color National Artists' Book Project. Flossie Martin Gallery. 1990. OCLC 29033208.

- ^ "Department History". visarts.ucsd.edu. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ^ "Faith Ringgold". Biography. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ^ "About Faith Ringgold".

- ^ Anon 2018

- ^ Russeth, Andrew. "The Storyteller: At 85, Her Star Still Rising, Faith Ringgold Looks Back on Her Life in Art, Activism, and Education", ARTnews, March 1, 2016. Retrieved February 6, 2017. "The artist's second husband, Burdette Ringgold (everyone calls him Birdie), went along too, carrying her paintings, as he always did. 'We never showed [galleries] books or slides,' Ringgold told me one morning in her studio at her home in Englewood, New Jersey."

- ^ Ringgold v. Black Entertainment Television, 126 F.3d 70 (2nd Cir. 1997).

- ^ Oler, Tammy (October 31, 2019). "57 Champions of Queer Feminism, All Name-Dropped in One Impossibly Catchy Song". Slate Magazine.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Ringgold, Faith (1987). "Being My Own Woman". Women's Studies Quarterly. 15 (1/2): 31–34 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Hettie Judah, "Faith Ringgold review – critique of racist America as relevant as ever", The Guardian, June 5, 2019.

- Anon (2018). "Artist, Curator & Critic Interviews". !Women Art Revolution – Spotlight at Stanford. Archived from the original on August 23, 2018. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

Further reading[]

- Melody Graulich; Mara Witzling, eds. (2001). "The Freedom to See what She Pleases: A Conversation with Faith Ringgold". Black feminist cultural criticism. Keyworks in cultural studies. Malden, Mass: Blackwell. ISBN 0631222391.

- Faith Ringgold Biography Activist, Painter, Civil Rights Activist, Women's Rights Activist, Author, Educator (1930–)

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Faith Ringgold |

- Official website

- Faith Ringgold Blog

- Interview with Faith Ringgold about "American People Series #20: Die", 1967

- Barbara Faith Company blog – everything about Faith Ringgold

- Faith Ringgold’s oral history video excerpts at The National Visionary Leadership Project

- Faith Ringgold on DVD, at work, her inspiration and craft – films by Linda Freeman, L&S Video

- Faith Ringgold Society , an organization devoted to the study of Ringgold's life and work

- Faith Ringgold at Library of Congress Authorities, with 31 catalog records

- Faith Ringgold at Brooklyn Museum, Feminist Art Statement

- American women painters

- African-American women artists

- Activists for African-American civil rights

- American contemporary painters

- Feminist artists

- 1930 births

- Living people

- American textile artists

- African-American feminists

- American feminists

- City College of New York alumni

- 20th-century American painters

- 20th-century American women artists

- American women printmakers

- 20th-century American printmakers

- People from Englewood, New Jersey

- Women textile artists

- 21st-century American women artists

- African-American painters

- African-American printmakers

- Quilters

- Harlem Renaissance