Free City of Danzig

Coordinates: 54°21′N 18°40′E / 54.350°N 18.667°E

Free City of Danzig Freie Stadt Danzig (German) Wolne Miasto Gdańsk (Polish) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1920–1939 | |||||||||

Flag

Coat of arms

| |||||||||

| Motto: "Nec Temere, Nec Timide" "Neither rashly nor timidly" | |||||||||

| Anthem: Für Danzig / Gdańsku | |||||||||

Danzig, surrounded by Germany and Poland | |||||||||

| Status | Free City under League of Nations protection | ||||||||

| Capital | Danzig | ||||||||

| Common languages | German · Polish

| ||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Danziger | ||||||||

| Government | Republic | ||||||||

| LoN High Commissioner | |||||||||

• 1919–1920 (first) | Reginald Tower | ||||||||

• 1937–1939 (last) | Carl J. Burckhardt | ||||||||

| Senate President | |||||||||

• 1920–1931 (first) | Heinrich Sahm | ||||||||

• 1939 (last) | Albert Forster[a] | ||||||||

| Legislature | Volkstag | ||||||||

| Historical era | Interwar period | ||||||||

• Established | 15 November 1920 | ||||||||

• Invasion of Poland | 1 September 1939 | ||||||||

• Annexed by Germany | 2 September 1939 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1923 | 1,966 km2 (759 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1923 | 366,730 | ||||||||

| Currency | Papiermark (1920–23) Danzig gulden (1923–39) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Poland | ||||||||

The Free City of Danzig (German: Freie Stadt Danzig; Polish: Wolne Miasto Gdańsk; Kashubian: Wòlny Gard Gduńsk) was a semi-autonomous city-state that existed between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland) and nearly 200 towns and villages in the surrounding areas. It was created on 15 November 1920[1][2] in accordance with the terms of Article 100 (Section XI of Part III) of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles after the end of World War I.

The Free City included the city of Danzig and other nearby towns, villages, and settlements that were primarily inhabited by Germans. As the treaty stated, the region was to remain separated from the post-war German Republic and from the newly independent Polish Republic, but it was not a sovereign state.[3] The Free City was under League of Nations protection and put into a binding customs union with Poland.

Poland was given certain rights pertaining to communication, the railways and port facilities in the city.[4] The Free City was created in order to give Poland access to a sizeable seaport.[5] In 1938, the Free City's population of 410,000 was 98% German, 1% Polish and 1% other.[6][7][8] In the 1920 Constituent Assembly election, the Polish Party received over 6% of the vote, but its percentage of votes later declined to about 3%.

In 1921, Poland began to develop the city of Gdynia, then a midsized fishing town. This completely new port north of Gdansk was established on territory awarded in 1919, the so-called Polish Corridor. By 1933, the commerce passing through Gdynia exceeded that of Danzig.[6] Notwithstanding this, Poland refused to relinquish trading and other rights awarded to it, further alienating the Danzigers.

By 1936, the city's senate had a majority of local Nazis, and agitation to rejoin Germany was stepped up.[9] Many Jews fled from German antisemitism, persecution, and oppression. After the German invasion of Poland in 1939, the Nazis abolished the Free City and incorporated the area into the newly formed Reichsgau of Danzig-West Prussia. The Nazis classified the Poles and Jews living in the city as subhumans, subjecting them to discrimination, forced labor, and extermination. Many were sent to their deaths at Nazi concentration camps, including nearby Stutthof (now Sztutowo, Poland).[10]

During the city's conquest by the Soviet Army in the early months of 1945, a substantial number of citizens fled or were killed. In 1945, the city officially became part of Poland in accordance with the Potsdam Agreement. In the period immediately after the war, many surviving Germans were expelled to West or East Germany, while members of the pre-war Polish ethnic minority started returning and new Polish settlers began to come. Gdańsk suffered severe underpopulation from these events and did not recover until the late 1950s.

Establishment[]

Periods of independence and autonomy[]

Danzig had an early history of independence. It was a leading player in the Prussian Confederation directed against the Teutonic Monastic State of Prussia. The Confederation stipulated with the Polish king, Casimir IV Jagiellon, that the Polish Crown would be invested with the role of head of state of western parts of Prussia (Royal Prussia). In contrast, Ducal Prussia remained a Polish fief. Danzig and other cities such as Elbing and Thorn financed most of the warfare and enjoyed a high level of city autonomy. Danzig used the title Royal Polish City of Danzig.

In 1569, when Royal Prussia's estates agreed to incorporate the region into the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the city insisted on preserving its special status. It defended itself through the costly Siege of Danzig in 1577 in order to preserve special privileges, and subsequently insisted on negotiating by sending emissaries directly to the Polish king.[11] Danzig's location as a deep-water port where the Vistula river met the Baltic Sea had made it into one of the wealthiest cities in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries as grain from Poland and Ukraine was shipped down the Vistula on barges to be loaded onto ships in Danzig, where it was shipped on to western Europe.[12] As many of the merchants shipping the grain from Danzig were Dutch, who built Dutch-style houses for themselves, leading to other Danzigers imitating them, the city was thus given a distinctively Dutch appearance.[12] Danzig become known as "the Amsterdam of the East", a wealthy seaport and trading crossroads that linked together the economics of western and eastern Europe, and whose location at where the Vistula flowed into the Baltic led to various powers competing to rule the city.[12]

Although Danzig became part of the Kingdom of Prussia in the Second Partition of Poland in 1793, Prussia was conquered by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1806, and in September 1807 Napoleon declared Danzig a semi-independent client state of the French Empire, known as the Free City of Danzig. It lasted seven years, until it was re-incorporated into the Kingdom of Prussia in 1814, after Napoleon's defeat at the Battle of Leipzig (Battle of Nations) by a coalition that included Russia, Austria, and Prussia. The city remained part of Prussia until 1920, becoming part of the Reich in 1871.

Point 14 of U.S. president Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points called for Polish independence to be restored and for Poland to have "secure access to the sea", a promise that implied that Danzig which occupied a strategic location where the Vistula river flowed into the Baltic sea, should become part of Poland.[12] At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, the Polish delegation led by Roman Dmowski asked for Wilson to honor point 14 of the 14 Points by transferring Danzig to Poland, arguing that Poland would not be economically viable without Danzig and that since the city had been part of Poland until 1793, it was rightfully part of Poland anyway.[13] However, Wilson had promised that national self-determination would be the basis of the Treaty of Versailles. As 90% of the people in Danzig in this period were German, the Allied leaders at the Paris Peace Conference compromised by creating the Free City of Danzig, a city-state in which Poland had certain special rights.[14] It was felt that including a city that was 90% German into Poland would be a violation of the principle of national self-determination, but at the same time the promise in the 14 Points of allowing Poland "secure access to the sea" gave Poland a claim on Danzig, hence the compromise of the Free City of Danzig.[14]

The Free City of Danzig was largely the work of British diplomacy as both the French Premier Georges Clemenceau and U.S. President Woodrow Wilson supported the Polish claim to Danzig, and it was only objections from the British Prime Minister David Lloyd George that prevented Danzig from going to Poland.[15] Despite creating the Free City, the British did not really believe in the viability of the Free City of Danzig with Lloyd George writing at the time: "France would tomorrow fight for Alsace if her right to it were contested. But would we make war for Danzig?".[15] The Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour wrote in the summer of 1918 that the Germans had such a ferocious contempt for Poles that it was unwise for Germany to lose any territory to Poland even if morally justified as the Germans would never accept losing land to the despised Poles and such a situation was bound to cause a war.[16] During the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, the British consistently sought to minimize German territorial losses to Poland under the grounds that the Germans had such an utter contempt for the Poles together with the rest of the Slavic peoples that such losses were bound to deeply wound their feelings and cause a war.[16] For all the bitterness of the French–German enmity, the Germans had a certain grudging respect for the French that did not extend to the Poles at all. During the Paris Peace Conference, a commission of inquiry chaired by a British historian, James Headlam-Morley, investigating where the borders between Germany and Poland should be, started to research Danzig's history.[17] Upon discovering that Danzig had been a Free City in the past, Headlam-Morley came up with what he regarded as a brilliant compromise solution under which Danzig would become a Free City again that would belong to neither Germany nor Poland.[17] As the British were opposed to Danzig becoming part of Poland and the French and the Americans to Danzig remaining part of Germany, Headlam-Morley's compromise of the Free City of Danzig was embraced.[17]

The rural areas around Danzig were overwhelmingly Polish and the representatives of the Polish farmers around Danzig complained about being included in the Free City of Danzig, stating they wanted to join Poland.[13][need quotation to verify] For their part, the representatives of the German population of Danzig complained about being severed from Germany, and constantly demanded that the Free City of Danzig be reincorporated into the Reich.[18] The Canadian historian Margaret MacMillan wrote that a sense of Danzig national identity never emerged during the Free City's existence, and the German population of Danzig always regarded themselves as Germans who had been unjustly taken out of Germany.[18] The loss of Danzig did indeed deeply hurt German national pride and in the interwar period, German nationalists spoke of the "open wound in the east" that was the Free City of Danzig.[19] However, until the building of Gdynia, almost all of Poland's exports went through Danzig, and Polish public opinion was opposed to Germany having a "choke-hold" on the Polish economy.[20]

Territory[]

The Free City of Danzig (1920–39) included the city of Danzig (Gdańsk), the towns of Zoppot (Sopot), Oliva (Oliwa), Tiegenhof (Nowy Dwór Gdański), Neuteich (Nowy Staw) and some 252 villages and 63 hamlets, covering a total area of 1,966 square kilometers (759 sq mi). The cities of Danzig (since 1818) and Zoppot (since 1920) formed independent cities (Stadtkreise), whereas all other towns and municipalities were part of one of the three rural districts (Landkreise), Danziger Höhe, (both seated in Danzig city) and , seated in Tiegenhof.

In 1928, its territory covered 1,952 km2 including 58 square kilometers of freshwater surface. The border had a length of 290.5 km, of which the coastline accounted for 66.35 km.[21]

Polish rights declared by Treaty of Versailles[]

The Free City was to be represented abroad by Poland and was to be in a customs union with it. The German railway line that connected the Free City with newly created Poland was to be administered by Poland, as were all rail lines in the territory of the Free City. On November 9, 1920, a convention that provided for the Presence of a Polish diplomatic representative in Danzig was signed between the Polish government and the Danzig authorities. In article 6, the Polish government undertook not to conclude any international agreements regarding Danzig without previous consultation with the Free City's government.[22]

A separate Polish post office was established, besides the existing municipal one.

League of Nations High Commissioners[]

Unlike Mandatory territories, which were entrusted to member countries, the Free City of Danzig (like the Territory of the Saar Basin) remained directly under the authority of the League of Nations. Representatives of various countries took on the role of High Commissioner:[citation needed]

| No. | Name | Period | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Reginald Thomas Tower | 1919–1920 | |

| 2 | Edward Lisle Strutt | 1920 | |

| 3 | Bernardo Attolico | 1920 | |

| 4 | Richard Cyril Byrne Haking | 1921–1923 | |

| 5 | 1923–1925 | ||

| 6 | 1925–1929 | ||

| 7 | 1929–1932 | ||

| 8 | 1932–1934 | ||

| 9 | Seán Lester | 1934–1936 | |

| 10 | Carl Jacob Burckhardt | 1937–1939 |

The League of Nations refused to let the city-state use the term of Hanseatic City as part of its official name; this referred to Danzig's long-lasting membership in the Hanseatic League.[23]

State Constabulary[]

With the creation of the Free City in the aftermath of World War I a security police force was created on 19 August 1919. On 9 April 1920, a military style marching band, the Musikkorps, was formed. Led by composer Ernst Stieberitz, the police band became well known in the city and abroad. In 1921, Danzig's government reformed the entire institution and established the Schutzpolizei, or protection police.[24] Helmut Froböss became President of the Police (i. e. Chief) on 1 April 1921. He served in this capacity until the German annexation of the city.[24]

The police initially operated from 12 precincts and 7 registration points. In 1926 the number of precincts was reduced to 7.[24]

After the Nazi takeover of the Senate, the police were increasingly used to suppress free speech and political dissent.[25] In 1933, Froböss ordered the left-wing newspapers Danziger Volksstimme and Danziger Landeszeitung to suspend publications for 2 months and 8 days respectively.[26]

By 1939, Polish-German relations had worsened and war seemed a likely possibility. The police began making plans to seize Polish installations within the city, in the event of conflict.[27] Ultimately the Danzig police participated in the September Campaign, fighting alongside the local SS and the German Army at the city's Polish post office and at Westerplatte.[27][28]

Even though the Free City was formally annexed by Nazi Germany in October 1939, the police force more or less continued to operate as a law enforcement agency. The Stutthof concentration camp, 35 km east of the city, was run by the President of the police as an internment camp from 1939 until November 1941.[29] Administration was finally dissolved when the city was occupied by the Soviets in 1945.

Population[]

The Free City's population rose from 357,000 (1919) to 408,000 in 1929; according to the official census, 95% were Germans,[30]:5, 11 with the rest mainly either Kashubians or Poles. According to E. Cieślak, the population registers of the Free City show that in 1929 the Polish population numbered 35,000, or 9.5% of the population.[31][need quotation to verify]

Henryk Stępniak estimates the 1929 Polish population as around 22,000, or around 6% of the population, increasing to around 13% in the 1930s.[7] Based on the estimated voting patterns (according to Stępniak many Poles voted for the Catholic Zentrumspartei instead of Polish parties), Stępniak estimates the number of Poles in the city to be 25–30% of Catholics living within it or about 30–36 thousand people.[32] Including around 4,000 Polish nationals who were registered in the city, Stępniak estimated the Polish population as 9.4–11% of population.[32] In contrast Stefan Samerski estimates about 10 percent of the 130,000 Catholics were Polish.[33] Andrzej Drzycimski estimates that Polish population at the end of 30s reached 20% (including Poles who arrived after the war).[34]

The Treaty of Versailles required that the newly formed state have its own citizenship, based on residency. German inhabitants lost their German citizenship with the creation of the Free City, but were given the right to re-obtain it within the first two years of the state's existence. Anyone desiring German citizenship had to leave their property and make their residence outside the Free State of Danzig area in the remaining parts of Germany.[4]

| Nationality | German | German and Polish |

Polish, Kashub, Masurian |

Russian, Ukrainian |

Hebrew, Yiddish |

Unclassified | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Danzig | 327,827 | 1,108 | 6,788 | 99 | 22 | 77 | 335,921 |

| Non-Danzig | 20,666 | 521 | 5,239 | 2,529 | 580 | 1,274 | 30,809 |

| Total | 348,493 | 1,629 | 12,027 | 2,628 | 602 | 1,351 | 366,730 |

| Percent | 95.03% | 0.44% | 3.28% | 0.72% | 0.16% | 0.37% | 100.00% |

Notable people born in the Free City of Danzig[]

- Eddi Arent (1925 in Danzig – 2013 in Munich) was a German actor,[35] cabaret artist and comedian. He appeared in 104 films between 1956 and 2002.

- Ike Aronowicz (1923 in Danzig – 2009 Israel)[36] captain of the immigrant ship SS Exodus, which unsuccessfully tried to dock in Mandatory Palestine with Holocaust survivors on July 11, 1947

- Elisabeth Becker (1923 in Danzig – executed 1946 in Biskupia Górka) was a concentration camp guard[37] in World War II.

- Ingrid van Bergen (born 1931 in Danzig) is a German film actress.[38] She has appeared in 100 films since 1954. Convicted of manslaughter in 1977

- Miltiades Caridis (1923 in Danzig – 1998 in Athens) was a German-Greek conductor, his family moved to Greece in 1938.

- Zygmunt Chychła (1926 in Gdańsk - 2009 in Hamburg) was a Polish boxer.[39] He won the Olympic gold medal for Poland at the 1952 Summer Olympics

- Anna M. Cienciala (1929 in Danzig – 2014 in Florida) was a Polish-American[40] historian and author

- Holger Czukay (1938 in Danzig – 2017 in Weilerswist) was a German musician,[41] co-founder of the krautrock group Can

- Horst Ehmke (1927 in Danzig – 2017 in Bonn) was a German lawyer, law professor and SPD politician,[42] served as Federal Minister of Justice (1969)

- Jörg-Peter Ewert (born 1938 in Danzig) is a German neurophysiologist[43] and researcher into Neuroethology

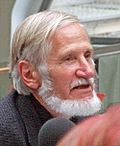

- Günter Grass (1927 in Danzig – 2015 in Lübeck) was a German novelist,[44] poet, playwright, illustrator, graphic artist, sculptor, and recipient of the 1999 Nobel Prize in Literature.

- Ursula Happe (1926 in Danzig – 2021) was a German swimmer and Olympic champion.[45] She competed at the 1956 Summer Olympics and won the gold medal in 200 m breaststroke

- Klaus Kinski (1926 in Zopot – 1991 in Lagunitas, California) was a controversial German actor.[46]

- Wanda Klaff (1922 in Danzig – executed 1946 in Biskupia Górka)[37] was a Nazi camp overseer

- Heinz-Hermann Koelle (1925 in Danzig - 2011 in Berlin) was an aeronautical engineer,[47] made the preliminary designs for Saturn I

- Erhard Krack (1931 in Danzig – 2000 in Berlin) was an East German politician and mayor of East Berlin from 1974 to 1990.

- Rutka Laskier (1929 in Danzig – 1943 in the Auschwitz concentration camp) was a Jewish teenager[48] who chronicled the three months of her life during the Holocaust

- Hanna-Renate Laurien (1928 in Danzig – 2010 Berlin) was a German[49] CDU politician

- Jack Mandelbaum (born 1927 in Danzig) is a Holocaust survivor[50]

- Rupert Neudeck (1939 in Danzig – 2016) correspondent for Deutschlandfunk and[51] founder of Cap Anamur a humanitarian organisation

- Zygmunt Pawłowicz (1927 in Danzig – 2010 in Gdańsk) ordained a Catholic priest in 1952,[52] was the Polish Auxiliary bishop of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Gdańsk from 1985 until 2005

- Avi Pazner (born 1937 in Danzig) is a retired Israeli diplomat[53]

- Richard J. Pratt (1934 in Danzig – 2009 in Victoria, Australia) was a prominent Australian businessman,[54] chairman of Visy Industries. His family moved to Australia in 1938

- Georg Preuß (1920 in Danzig – 1991 Clenze) was a mid-ranking commander in the Waffen-SS, a convicted war criminal.

- Henry Rosovsky (born 1927 in Danzig) is an economic historian,[55] specializing in East Asia, born of Russian Jewish parents

- Hermann Salomon (born 1938 in Danzig) is a German former javelin thrower[56] who competed in the 1960, 1964 and the 1968 Summer Olympics

- Meir Shamgar (born 1925 in Danzig)[57] was President of the Israeli Supreme Court 1983/1995.

- Zalman Shoval (born 1930 in Danzig) is an Israeli politician[58] and diplomat

- Wolfgang Völz (1930 in Danzig – 2018 in Berlin) was a German actor,[59] known for his roles in theatre plays, TV shows, feature films and taped radio shows

- Zdzisław Kuźniar (born 1931 in Gdańsk) is a Polish actor[60]

- F. K. Waechter (1937 in Danzig – 2005 in Frankfurt) was a German cartoonist, author and playwright

Religion[]

In 1924, 54.7% of the populace was Protestant (220,731 persons, mostly Lutherans within the united old-Prussian church), 34.5% was Roman Catholic (140,797 persons), and 2.4% Jewish (9,239 persons). Other Protestants included 5,604 Mennonites, 1,934 Calvinists (Reformed), 1,093 Baptists, 410 Free Religionists, as well as 2,129 dissenters, 1,394 faithful of other religions and denominations, and 664 irreligionists.[61][62] The Jewish community grew from 2,717 in 1910 to 7,282 in 1923, and 10,448 in 1929, many of them immigrants from Poland and Russia.[63]

Regional Synodal Federation of the Free City of Danzig[]

The mostly Lutheran and partially Reformed congregations situated in the territory of the Free City, which previously used to belong to the Ecclesiastical Province of West Prussia of the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union (EKapU), were transformed into the Regional Synodal Federation of the Free City of Danzig after 1920. The executive body of that ecclesiastical province, the consistory (est. 1 November 1886), was seated in Danzig. After 1920 it was restricted in its responsibility to those congregations within the Free City's territory.[64] General Superintendent (1920–1933) and Bishop (1933–1945) presided over the consistory, one after another.

Unlike the Second Polish Republic, which opposed the cooperation of the with EKapU, Volkstag and Senate of Danzig approved cross-border religious bodies. Danzig's Regional Synodal Federation — just as the regional synodal federation of the autonomous Memelland — retained the status of an ecclesiastical province within EKapU.[65]

After the German annexation of the Free City in 1939, the EKapU merged the Danzig regional synodal federation in 1940 into the Ecclesiastical Region of Danzig-West Prussia. This included the Polish congregations of the United Evangelical Church in Poland in the homonymous Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia and the German congregations in the West Prussia governorate. Danzig's consistory functioned as an executive body for that region. With the flight and expulsion of most ethnically German Protestant parishioners from the area of the Free City of Danzig between 1945 and 1948, the congregations vanished.

In March 1945, the consistory had relocated to Lübeck and opened a refugee centre for Danzigers (Hilfsstelle beim evangelischen Konsistorium Danzig) led by Upper Consistorial Councillor . The Lutheran congregation of St. Mary's Church could relocate its valuable parament collection and the presbytery granted it on loan to St. Annen Museum in Lübeck after the war. Other Lutheran congregations of Danzig could reclaim their church bells, which the Wehrmacht had requisitioned as non-ferrous metal for war purposes since 1940, but which had survived, not yet melted down, in storage (e.g. ) in the British zone of occupation. The presbyteries granted them usually to Northwestern German Lutheran congregations which had lost bells due to the war.

Diocese of Danzig of the Roman Catholic Church[]

The 36 Catholic parishes in the territory of the Free City in 1922 used to belong in equal shares to the Diocese of Culm, which was mostly Polish, and the Diocese of Ermland, which was mostly German. While the Second Polish Republic wanted all the parishes within the Free City to form part of Polish Culm, Volkstag and Senate wanted them all to become subject to German Ermland.[66] In 1922 the Holy See suspended the jurisdictions of both dioceses over their parishes in the Free State and established an exempt apostolic administration for the territory.[66]

The first apostolic administrator was Edward O'Rourke (born in Minsk and of Irish ancestry) who became Bishop of Danzig on the occasion of the elevation of the administration to an exempt diocese in 1925. He was naturalised as Danziger on the same occasion. In 1938 he resigned after quarrels with the Nazi-dominated Senate of Danzig on appointments of parish priests of Polish ethnicity.[67] The senate also instigated the denaturalisation of O'Rourke, who subsequently became a Polish citizen. O'Rourke was succeeded by Bishop Carl Maria Splett, a native from the Free City area.

Splett remained bishop after the German annexation of the Free City. In early 1941, he applied for admitting the Danzig diocese as member in Archbishop Adolf Bertram's Eastern German Ecclesiastical Province and thus at the Fulda Conference of Bishops; however, Bertram, also speaker of the Fulda conference, rejected the request.[68] Any arguments that the Free City of Danzig had been annexed to Nazi Germany did not impress Bertram since Danzig's annexation lacked international recognition. Until the reorganization of the Catholic dioceses in Danzig and the formerly eastern territories of Germany the diocesan territory remained unaltered and the see exempt. However, with the replacement of Danzig's population between 1945 and 1948 by mostly Catholic Poles, the number of Catholic parishes increased and most formerly Protestant churches were taken over for Catholic services.

Jewish Danzigers[]

Since 1883 most of the Jewish congregations in the later territory of Free State had merged into the Synagogal Community of Danzig. Only the Jews of Tiegenhof ran their own congregation until 1938.

Danzig became a centre of Polish and Russian Jewish emigration to North America. Between 1920 and 1925 60,000 Jews emigrated via Danzig to the US and Canada. At the same time, between 1923 and 1929, Danzig's own Jewish population increased from roughly 7,000 to 10,500.[69] Native Jews and newcomers established themselves in the city and contributed to its civic life, culture and economy. Danzig became a venue for international meetings of Jewish organisations, such as the convention of delegates from Jewish youth organisations of various nations, attended by David Ben-Gurion, which founded the on 2 September 1924 in the Schützenhaus venue. On 21 March 1926 the Zionistische Organisation für Danzig convened delegates of Hechalutz from all over for the first conference in Danzig using Hebrew as common language, also attended by Ben Gurion.

With a Nazi majority in the Volkstag and Senate, anti-Semitic persecution and discrimination occurred unsanctioned by the authorities. In contrast to Germany, which exercised capital outflow control since 1931, emigration of Danzig's Jews was nonetheless somewhat easier, with capital transfers enabled by the Bank of Danzig. Moreover, the comparatively few Danzig Jews were offered easier refuge in safe countries because of favorable Free City migration quotas.

After the anti-Jewish riots of Kristallnacht of 9/10 November 1938 in Germany, similar riots took place on 12/13 November in Danzig.[70][71] The Great Synagogue was taken over and demolished by the local authorities in 1939. Most Jews had already left the city, and the Jewish Community of Danzig decided to organize its own emigration in early 1939.[72]

Politics[]

Government[]

| No. | Portrait | Name (Born-Died) |

Term of office | Political Party | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Took office | Left office | Time in office | ||||

| Presidents of the Danzig Senate | ||||||

| 1 | Heinrich Sahm (1877–1939) | 6 December 1920 | 10 January 1931 | 10 years, 35 days | Independent | |

| 2 | Ernst Ziehm (1867–1962) | 10 January 1931 | 20 June 1933 | 2 years, 161 days | DNVP | |

| 3 | Hermann Rauschning (1887–1982) | 20 June 1933 | 23 November 1934 | 1 year, 156 days | NSDAP | |

| 4 | Arthur Greiser (1897–1946) | 23 November 1934 | 23 August 1939 | 4 years, 273 days | NSDAP | |

| State President | ||||||

| 5 | Albert Forster (1902–1952) | 23 August 1939 | 1 September 1939 | 9 days | NSDAP | |

The Free City was governed by the Senate of the Free City of Danzig, which was elected by the parliament (Volkstag) for a legislative period of four years. The official language was German,[73] although the usage of Polish was guaranteed by law.[74][75] The political parties in the Free City corresponded with the political parties in Weimar Germany; the most influential parties in the 1920s were the conservative German National People's Party, the Social Democratic Party of the Free City of Danzig and the Catholic Centre Party. A Communist Party was founded in 1921 with its origins in the Spartacus League and the Communist Party of East Prussia. Several liberal parties and Free Voter's Associations existed and ran in the elections with varying success. A Polish Party represented the Polish minority and received between 3% (1933) and 6% (1920) of the vote (in total, 4,358 votes in 1933 and 9,321 votes in 1920).[76]

Initially, the Nazi Party had only a small amount of success (0.8% of the vote in 1927) and was even briefly dissolved.[23] Its influence grew with the onset of difficult economic times and the increasing popularity of the Nazi Party in Germany proper. Albert Forster became the Gauleiter in October 1930. The Nazis won 50 percent of votes in the Volkstag elections of 28 May 1933, and took control of the Senate in June 1933, with Hermann Rauschning becoming President of the Senate of Danzig.

Rauschning was removed from his position by Forster and replaced by Arthur Greiser in November 1934.[70] He later appealed to the public not to vote for the Nazis in the 1935 elections.[23] Political opposition to the Nazis was repressed[77] with several politicians being imprisoned and murdered.[78][79] The economic policy of Danzig's Nazi-led government, which increased the public expenditures for employment-creation programs[80] and the retrenchment of financial aid from Germany led to a devaluation of more than 40% of the Danziger Gulden in 1935.[30][81][82][83][84][85] The Gold reserves of the Bank of Danzig declined from 30 million Gulden in 1933 to 13 million in 1935 and the foreign asset reserve from 10 million to 250,000 Gulden.[86] In 1935, Poland protested when Danzig's Senate reduced the value of the Gulden so that it would be the same as the Polish zloty.[87]

As in Germany, the Nazis introduced laws mirroring the Enabling Act and Nuremberg laws (November 1938);[88] existing parties and unions were gradually banned. The presence of the League of Nations however still guaranteed a minimum of legal certainty. In 1935, the opposition parties, except for the Polish Party, filed a lawsuit to the Danzig High Court in protest against the manipulation of the Volkstag elections.[23][70] The opposition also protested to the League of Nations, as did the Jewish Community of Danzig.[89][90] The number of members of the Nazi Party in Danzig increased from 21,861 in June 1934 to 48,345 in September 1938.[91]

Foreign relations[]

Foreign relations were handled by the United Kingdom. In 1927, the Free City of Danzig sent a military advisory mission to Bolivia. The Bolivian government of Hernando Siles Reyes wanted to continue the pre-World War I German military mission but the Treaty of Versailles prohibited that. The German officers, including Ernst Röhm, were transferred to the Danzig police force and then sent to Bolivia. In 1929, after problems with the mission, the British embassy handled the return of the German officers.[92]

German-Polish tensions[]

The rights of the Second Polish Republic within the territory of the Free City were stipulated in the Treaty of Paris of 9 November 1920 and the Treaty of Warsaw of 24 October 1921.[93] The details of the Polish privileges soon became a permanent matter of disputes between the local populace and the Polish State. While the representatives of the Free City tried to uphold the city's autonomy and sovereignty, Poland sought to extend its privileges.[94]

Throughout the Polish–Soviet War, local dockworkers went on strike and refused to unload ammunition supplies for the Polish Army. While the ammunition was finally unloaded by British troops,[95] the incident led to the establishment of a permanent ammunition depot at the Westerplatte and the construction of a trade and naval port in Gdynia,[96] whose total exports and imports surpassed those of Danzig in May 1932.[97] In December 1925, the Council of the League of Nations agreed to the establishment of a Polish military guard of 88 men on the Westerplatte peninsula to protect the war material depot.[98][99]

During the interwar period the Polish minority was heavily discriminated against by the German population, which openly attacked its members using racist slurs and harassment, and attacks against the Polish consulate by German students were praised by authorities.[100] In June 1932, a crisis broke out when the Polish destroyer ORP Wicher was sent into Danzig harbour without the permission of the Senate to greet a visiting squadron of British destroyers.[101] The crisis was resolved when the Free City granted more access rights to the Polish Navy in exchange for a promise to not take the Wicher back into Danzig harbour.[101]

Several disputes between Danzig and Poland occurred in the sequel. The Free City protested against the Westerplatte depot, the placement of Polish letter boxes within the City[102] and the presence of Polish war vessels at the harbour.[103] The attempt of the Free City to join the International Labour Organization was rejected by the Permanent Court of International Justice at the League of Nations after protests of the Polish ILO delegate.[104][105]

After Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany, the Polish military doubled the number of 88 troops at Westerplatte in order to test the reaction of the new chancellor. After protests the additional troops were withdrawn.[106] Nazi propaganda used these events in the Volkstag elections of May 1933, in which Nazis won absolute majority.[107]

Until June 1933, the High Commissioner decided in 66 cases of dispute between Danzig and Poland; in 54 cases one of the parties appealed to the Permanent Court of International Justice.[108] Subsequent disputes were resolved in direct negotiations between the Senate and Poland after both had agreed to abstain from further appeals to the International Court in the summer of 1933 and bilateral agreements were concluded.[109]

In the aftermath of the German-Polish Non-Aggression Pact of 1934, Danzig–Polish relations improved and Adolf Hitler instructed the local Nazi government to cease anti-Polish actions.[110] In return, Poland did not support the actions of the anti-Nazi opposition in Danzig. The Polish Ambassador to Germany, Józef Lipski, stated in a meeting with Hermann Göring[111]

"... that a National Socialist Senate in Danzig is also most desirable from our point of view, since it brought about a rapprochement between the Free City and Poland, I would like to remind him that we have always kept aloof from internal Danzig problems. In spite of approaches repeatedly made by the opposition parties, we rejected any attempt to draw us into action against the Senate. I mentioned quite confidentially that the Polish minority in Danzig was advised not to join forces with the opposition at the time of elections."

When Carl J. Burckhardt became High Commissioner in February 1937, both Poles and Germans openly welcomed his withdrawal, and Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs Józef Beck notified him not to "count on the support of the Polish State" in the case of difficulties with the Senate or the Nazi Party.[112]

While the Senate appeared to respect the agreements with Poland, the "Nazification of Danzig proceeded relentlessly"[113] and Danzig became a springboard for anti-Polish propaganda among the German and Ukrainian minority in Poland.[114] The Catholic Bishop of Danzig, Edward O'Rourke, was forced to withdraw after he had tried to implement four additional Polish nationals as parish priests in October 1937.[67]

Danzig crisis[]

The German policy openly changed immediately after the Munich Conference in October 1938, when German Minister of Foreign Affairs Joachim von Ribbentrop demanded the incorporation of the Free City into the Reich.[115] The Polish ambassador to Germany, Jozef Lipski, declined Ribbentrop's offer, saying that Polish public opinion would not tolerate the Free City joining Germany and predicated that if Warsaw allowed that to happen, then the Sanation military dictatorship that had ruled Poland since 1926 would be overthrown.[19] On 24 March 1939, the Polish Foreign Minister, Colonel Jozef Beck, who was part of the triumvirate which ruled the Sanation regime and largely ran foreign policy on his own, told a meeting of the Polish cabinet that Poland should go to war if Germany made any attempt to alter the status of Danzig.[19] Beck stated that Danzig "regardless of what it is worth as an object" had become a "symbol" in Poland that was so important that Poland should go to war over the issue.[19] Aside from the possibility that a revolution in Poland might overthrow the Sanation regime should it allow Danzig to be returned to Germany, Beck as part of his plans for a "Third Europe" (i.e. a block of Eastern European states under Polish leadership) had sought to develop economic relations with Sweden and Finland.[116] Beck envisioned both Sweden and Finland joining the "Third Europe" block, and German plans to take back Danzig threatened to allow Germany a "choke-hold" on Poland's main link to the sea as the port facilities at Danzig were still better developed than those at Gdynia.[116] Ernst von Weizsäcker on 29 March 1939 told the Danzig government the Reich would carry out a policy to the Zermürbungspolitik (point of destruction) towards Poland, saying a compromise solution was not wanted, and on 5 April 1939 told Hans-Adolf von Moltke under no conditions was he to negotiate with the Poles.[117]

On 31 March 1939, the British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, announced in the House of Commons a "guarantee" of Polish independence, stating that Britain would go to war with Germany if there was an attempt to end Polish independence, though Chamberlain pointedly excluded the borders of Poland from the "guarantee".[19] In April 1939, High Commissioner Burckhardt was told by the Polish Commissioner-General that any attempt to alter its status would be answered with armed resistance on the part of Poland.[118] Beck had not abandoned hopes of negotiating a settlement with Germany.[119] During the spring and summer of 1939 it was the aim of British foreign policy to build a "peace front" embracing Britain, France, the Soviet Union and a number of other European states such as Poland, Romania, Yugoslavia, Greece and Turkey with the aim of "containing" Germany.

Beck made it clear that he wanted no Polish-Soviet treaty to go along with the British-inspired "peace front" since an alliance with the Soviets would rule out any possibility of a settlement with Germany, which he still had hopes of reaching.[119] Beck declined to have Polish diplomats take part in the talks between British, French and Soviet diplomats about having the Soviet Union join the "peace front", and during a visit to London in April 1939 he declined British offers to create a military alliance of Britain, Poland and Romania designed to block the Reich's offers to expand its influence in Eastern Europe.[119] The Polish historian Anita Prazmowska wrote that Beck's refusal of the British offers of assistance was partly due to his "inflated sense of self-importance and the general overestimation of Poland's military potential" as he believed that Poland was one of the world's great powers that could defeat Germany on its own, but also due to his desire not have Poland join the anti-German "peace front" at a time when he still believed that he could settle the Danzig issue.[119] During his visit to London on 4–6 April 1939 Beck told Chamberlain that any effort to include the Soviet Union in the "peace front" would cause the very war it was supposed to prevent, and wanted to exclude the Soviet Union from the "peace front" for that reason.[120] Before the Danzig crisis, the Polish General Staff had devoted far more time to planning a possible war with the Soviet Union rather than with Germany, and even after the Danzig crisis began, planning for a possible war with Germany went about in a rather haphazard and causal manner suggesting the Polish high command did not see war with Germany as very likely in 1939.[121] On 5 May 1939, Beck in a speech broadcast on Polish radio stated that Poland wanted peace but that "peace...has its price, high but definable. We in Poland do not recognize the conception of peace at any price. There is only one thing..which is without price, and that is honor".[122]

All through the spring and summer of 1939 there was a massive media campaign in Germany demanding the immediate return of the Free City of Danzig to Germany under the slogan "Home to the Reich!". However, the Danzig crisis was a just a pretext for war. Ribbentrop ordered Count Hans-Adolf von Moltke, the German ambassador to Poland, not to negotiate with the Poles over Danzig as it was always Ribbentrop's great fear that the Poles might actually agree to the Free City returning to Germany, thereby depriving the Reich out of its pretext for attacking Poland.[123] However, the German propaganda that all the Reich wanted was to bring Danzig home did some effect abroad. In April 1943, when mass graves of the Polish officers massacred by the NKVD in Katyn Wood were discovered, the Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King wrote in his diary that it was the Poles who caused the outbreak of the war in 1939 by refusing to give in to Hitler's demand that Danzig be allowed to rejoin Germany, and as such it was the Poles' own fault for the Katyn Wood massacre and everything else they had suffered since 1939.[124] The British historian Victor Rothwell described King's view that the Poles had caused their own suffering as one motivated by spite and his resentment at being pressured by public opinion into declaring war on Germany despite his own inclinations towards neutrality.[124] From distant New Zealand, the Prime Minister Michael Joseph Savage offered to return Western Samoa, which had once been the colony of German Samoa together with the rest of the former German islands in the Pacific held by New Zealand, in exchange for Germany promising not to use violence to alter the status of Danzig.[124]

However, in 1938, the Reich government had first demanded autonomy for the Sudetenland region and after Prague had conceded the demand for autonomy, had laid claim to the Sudetenland. On 15 March 1939, Germany had occupied the Czech part of Czecho-Slovakia, which had done immense damage to Hitler's claim that he was only trying to undo an "unjust" Treaty of Versailles by bringing all of the ethnic Germans "home to the Reich". The British Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax late in August 1939 told Herbert von Dirksen, the German ambassador in London:

“Last year the German government put forward the demand for the Sudetenland on purely racial grounds; but subsequent events proved that this demand was only put forward as a cover for the annihilation of Czechoslovakia. In view of this experience… it is not surprising that the Poles and we ourselves are afraid that the demand for Danzig is only a first move towards the destruction of Poland’s independence”.[125]

Tensions escalated into the Danzig crisis during the summer of 1939. F.M Shepard, the British consul in Danzig, reported that the Danzig Nazis were bringing arms from Germany and building fortifications.[126] In July 1939, the British government reluctantly extended its "guarantee" of Poland to the status of Free City of Danzig, stating a German attempt to take Danzig would be a casus belli.[127] At the beginning of August, the Senate told Warsaw that henceforward the Free City would no longer recognize the authority of Polish customs officers in Danzig, which led Beck in response to warn that the Senate did not have the right to disregard the terms of the Treaty of Versailles and that the German government also did not have the right to speak for Danzig.[128] Much to the chagrin of the British Foreign Office, Warsaw did not consult Britain first when it issued a warning that the Polish Air Force would bomb Danzig if the authority of Polish customs officers continued to be ignored.[128] The Senate backed down while the British who were informed after the fact of the Polish decision to confront the Free City were thrown into panic over the possibility of an armed clash in Danzig plunging Europe into war.[128] The British ambassador to Poland, Sir Howard William Kennard, sought in vain for a promise from Colonel Beck that Poland would take no action in Danzig without first obtaining British approval.[128] Beck disliked Kennard and kept him in the dark about what Poland would do if Danzig voted to rejoin Germany, but also about the state of German-Polish relations, much to the vexation of the Foreign Office.[129]

In the middle of August, Beck offered a concession, saying that Poland was willing to give up its control of Danzig's customs, a proposal which caused fury in Berlin.[130] However, the leaders of the Free City sent a message to Berlin on 19 August 1939 saying: "Gauleiter Forster intends to extend claims...Should the Poles yield again it is intended to increase the claims further in order to make accord impossible".[130] The same day a telegram from Berlin expressed approval with the proviso: "Discussions will have to be conducted and pressure exerted against Poland in such a way that responsibility for failure to come to an agreement and the consequences rest with Poland".[130] On 23 August 1939, Albert Forster, the Gauleiter of Danzig, called a meeting of the Senate that voted to have the Free City rejoin Germany, raising tensions to the breaking point.[131] The same meeting appointed Forster the Danzig State President, through this was due to Forster's long-running rivalry with Arthur Greiser, a völkisch fanatic who regarded Forster as too soft on the Poles. Both the appointment of Forster as State President and the resolution calling for the Free City to rejoin the Reich were violations of the charter the League of Nations had given Danzig in 1920, and the matter should have been taken to the League of Nations's Security Council for discussion.[128]

Since these violations of the Danzig charter would have resulted in the League deposing the Danzig's Nazi government, both the French and British prevented the matter from being referred to the Security Council.[132] Instead the British and French applied strong pressure on the Poles not to send in a military force to depose the Danzig government, and appoint a mediator to resolve the crisis.[133] By late August 1939, the crisis continued to escalate with the Senate confiscating on 27 August 1939 stocks of wheat, salt and petrol that belonged to the Polish businesses that were in the process of being exported or imported via the Free City, an action that led to sharp Polish complaints.[134] The same day, 200 Polish workers at the Danzig shipyards were fired without severance pay and their identification papers revoked, meaning that they legally could not live in Danzig anymore.[135] The Danzig government imposed food rationing, the Danzig newspapers took a militantly anti-Polish line, and almost everyday there were "incidents" on the border with Poland.[135] Ordinary people in Danzig were described as being highly worried in the last days of August 1939 as it become apparent that war was imminent.[135] In the meantime, the German battleship Schleswig-Holstein had arrived in Danzig on 15 August.[133] Originally, it was planned to send the light cruiser Königsberg to Danzig for what was described as a "friendship visit", but it was decided at the last minute that a ship with more firepower was needed, leading to the Schleswig-Holstein with its 11-inch (280 mm) guns being substituted.[136] Upon anchoring in Danzig harbor, the Schleswig-Holstein ominously aimed its guns at the Polish Military Depot on the Westerplatte peninsula in a provocative gesture that further raised the tensions in the Free City.[133]

At about 4:48am on 1 September 1939, the Schleswig-Holstein opened fire on the Westerplatte, firing the first shots of World War II.[137]

Second World War and aftermath[]

World War II began with the shelling of the Westerplatte on 1 September 1939. Gauleiter Forster entered the High Commissioner's residence and ordered him to leave the City within two hours,[138] and the Free City was formally incorporated into the newly formed Reichsgau of Danzig-West Prussia. Local SS and the police cooperated with the Germans with expelling Polish authorities from in and around the city. Polish civilian Post Office employees had received military training and were in possession of a cache of weapons – mostly pistols, three light machine guns, and some hand grenades – and were thus able to defend the Polish Post Office for fifteen hours. Upon their surrender, they were tried and executed. (The sentence was officially revoked by a German court as illegal in 1998.)[139][140] The Polish military forces in the city held out until 7 September.

Up to 4,500 members of the Polish minority were arrested with many of them executed.[141] In the city itself hundreds of Polish prisoners were subjected to cruel executions and experiments, which included castration of men and sterilization of women considered dangerous to the "purity of Nordic race" and beheading by guillotine.[142] The judicial system was one of the main tools of extermination policy towards Poles led by Nazi Germany in the city and verdicts were motivated by statements that Poles were subhuman.[143] By the end of the Second World War, nearly all the city had been reduced to ruins. On 30 March 1945, the city was taken by the Red Army.

At the Yalta Conference in February 1945, the Allies agreed that the city would become part of Poland.[144] No formal treaty has ever altered the status of the Free City of Danzig, and its incorporation into Poland has rested upon the general acquiescence of the international community.[145] In 1947, a Free City of Danzig Government in Exile was established.

The expulsion of the pre-war inhabitants started already before the decisions of the Potsdam conference of August 1945. From June to October an estimated number of 60,000 residents were expelled by Polish authorities, often units of the Polish Armed Forces, the Polish State Security and the Milicja Obywatelska encircled certain areas and forced the inhabitants to make room for newly arrived Polish settlers. About 20,000 Germans left on their own and by late 1945 between 10,000 and 15,000 pre-war inhabitants remained.[146] By 1950, around 285,000 fled and expelled citizens of the former Free City were living in Germany,[citation needed] and 13,424 citizens of the former Free City had been "verified" and granted Polish citizenship.[147] By 1947, 126,472 Danzigers of German ethnicity were expelled to Germany from Gdańsk, and 101,873 Poles from Central Poland and 26,629 from Soviet-annexed Eastern Poland took their place (these figures refer to the city of Gdańsk itself, not to the whole area of pre-war Free City).[147]

Origin of the post-war population[]

This section does not cite any sources. (June 2020) |

During the Polish post-war census of December 1950, data about the pre-war places of residence of the inhabitants as of August 1939 was collected. In case of children born between September 1939 and December 1950, their origin was reported based on the pre-war places of residence of their mothers. Thanks to this data it is possible to reconstruct the pre-war geographical origin of the post-war population. The same territory which corresponded to pre-war Free City of Danzig was inhabited in December 1950 by:

| Region (within 1939 borders): | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Autochthons (1939 DE/FCD citizens) | 35,311 | 12,1% |

| Polish expellees from Kresy (USSR) | 55,599 | 19,0% |

| Poles from abroad except the USSR | 2,213 | 0,8% |

| Resettlers from the City of Warsaw | 19,322 | 6,6% |

| From Warsaw region (Masovia) | 22,574 | 7,7% |

| From Białystok region and Sudovia | 7,638 | 2,6% |

| From pre-war Polish Pomerania | 72,847 | 24,9% |

| Resettlers from Poznań region | 10,371 | 3,5% |

| Katowice region (East Upper Silesia) | 2,982 | 1,0% |

| Resettlers from the City of Łódź | 2,850 | 1,0% |

| Resettlers from Łódź region | 7,465 | 2,6% |

| Resettlers from Kielce region | 16,252 | 5,6% |

| Resettlers from Lublin region | 19,002 | 6,5% |

| Resettlers from Kraków region | 5,278 | 1,8% |

| Resettlers from Rzeszów region | 6,200 | 2,1% |

| place of residence in 1939 unknown | 6,559 | 2,2% |

| Total pop. in December 1950 | 292,463 | 100,0% |

At least 85% of the population as of December 1950 were post-war newcomers, but over 10% of inhabitants were still pre-war Danzigers (most of them members of pre-war Polish and Kashubian minorities in the Free City of Danzig). Another 25% came from neighbouring areas of pre-war Polish Pomerania. Almost 20% were Poles from areas of former Eastern Poland annexed by the USSR (many from Wilno Voivodeship). Several percent came from the city of Warsaw, which had been largely destroyed in 1944.

In fiction[]

Historical Danzig is the setting for several works of Günter Grass, including his Danzig Trilogy novels The Tin Drum, Cat and Mouse and Dog Years, as well as in his memoirs. Grass grew up in the Danzig suburb of Langfuhr (now Wrzeszcz).[citation needed]

See also[]

- Administrations of Danzig before April 1945

- Allgemeiner Arbeiterverband der Freien Stadt Danzig

- Areas annexed by Nazi Germany

- Danzig Corridor

- Danzig Research Society

- Alfons Flisykowski

- History of Gdańsk

References[]

- ^ As "Head of State"

- ^ Loew, Peter Oliver (February 2011). Danzig – Biographie einer Stadt (in German). C.H. Beck. p. 189. ISBN 978-3-406-60587-1.

- ^ Samerski, Stefan (2003). Das Bistum Danzig in Lebensbildern (in German). LIT Verlag. p. 8. ISBN 978-3-8258-6284-8.

- ^ Kaczorowska, Alina (2010-07-21). Public International Law. Routledge. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-203-84847-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Yale Law School. "The Versailles Treaty June 28, 1919: Part III". The Avalon Project. Archived from the original on February 14, 2008. Retrieved May 3, 2007.

- ^ Chestermann, Simon (2004). You, the People; United Nations, Transitional Administration and State building. Oxford University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-19-926348-6. Retrieved 2011-04-26.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Encyclopaedia Britannica Year Book for 1938", p.193-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Zapiski historyczne: Volume 60, page 256, Towarzystwo Naukowe w Toruniu. Wydział Nauk Historycznych – 1995

- ^ Mason, John Brown. The Danzig Dilemma; a Study in Peacemaking by Compromise. pp. 4–5.

- ^ Levine, Herbert S., Hitler's Free City: A History of the Nazi Party in Danzig, 1925–39 (University of Chicago Press, 1970), p. 102.

- ^ Blatman, Daniel (2011). The Death Marches, The Final Phase of Nazi Genocide. Harvard University Press. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-0674725980.

- ^ Pelczar, Marian (1947). Polski Gdańsk (in Polish). Biblioteka Miejska.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Macmillan, Margaret Paris 1919, New York: Random House page 211

- ^ Jump up to: a b Macmillan, Margaret Paris 1919, New York: Random House page 211.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Macmillan, Margaret Paris 1919, New York: Random House page 218.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rothwell, Victor The Origins of the Second World War, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001 pages 106-107.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rothwell, Victor The Origins of the Second World War, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001 page 11.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Overy, Richard & Wheatcroft, Andrew The Road to War, Random House: London 2009 page 2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Macmillan, Margaret Paris 1919, New York: Random House page 219.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Overy, Richard & Wheatcroft, Andrew The Road to War, Random House: London 2009 page 16.

- ^ Overy, Richard & Wheatcroft, Andrew The Road to War, Random House: London 2009 page 3.

- ^ Wagner, Richard (1929). Die Freie Stadt Danzig. Taschenbuch des Grenz- und Auslanddeutschtums (in German) (2., Auflage / ed.). Berlin: Deutscher Schutzbund Verlag. p. 3.

- ^ Text in League of Nations Treaty Series, vol. 6, pp. 190–207.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Matull, Wilhelm (1973). "Ostdeutschlands Arbeiterbewegung: Abriß ihrer Geschichte, Leistung und Opfer" (PDF) (in German). Holzner. p. 419.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Polizei der Freie Stadt Danzig". www.danzig-online.pl.

- ^ Policja. Kwartalnik kadry kierowniczej Policji (in Polish)

- ^ HeinOnline 15 League of Nations (1934) (translated from German)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Danzig: Der Kampf um die polnische Post (in German)

- ^ Williamson, D. G. Poland Betrayed: The Nazi-Soviet Invasions of 1939 p. 66

- ^ United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Holocaust Encyclopedia - Danzig

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mason, John Brown (1946). The Danzig Dilemma, A Study in Peacemaking by Compromise. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2444-9. Retrieved 2011-04-26.

- ^ Cieślak, E Biernat, C (1995) History of Gdańsk, Fundacji Biblioteki Gdanskiej, P455

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ludność polska w Wolnym Mieście Gdańsku, 1920–1939, page 37, Henryk Stępniak, Wydawnictwo "Stella Maris", 1991, "Przyjmując, że Polacy gdańscy stanowili 25 — 30% ogólnej liczby ludności katolickiej Wolnego Miasta Gdańska, liczącej w 1920 r. około 110 000 osób, można ustalić, że w liczbach bezwzględnych stanowiło można ustalić, że w liczbach bezwzględnych stanowiło to 30- – 36 tyś. osób. Jeśli do liczby tej dodamy ok. 4 tyś. ludności obywatelstwa polskiego, otrzymamy łącznie ok. 9,4–11% ogółu ludności."

- ^ Samerski, Stefan (2003). Das Bistum Danzig in Lebensbildern (in German). LIT Verlag. p. 8. ISBN 978-3-8258-6284-8.

- ^ Stuthoff Zeszyty 4 4 Stanislaw Mikos Recenzje i omówienia Andrzej Drzycimski, Polacy w Wolnym Mieście Gdańsku /1920 – 1933/. Polityka Seantu gdańskiego wobec ludności polskiej Wrocław – Warszawa – Kraków – Gdańsk 1978,

- ^ IMDb.com retrieved 21 October 2017

- ^ The New York Times December 24, 2009 retrieved 21 October 2017

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stutthof Trial. Female guards in Nazi concentration camps Archived 2008 retrieved 21 October 2017

- ^ IMDb retrieved 21 October 2017

- ^ Olympic DB retrieved 21 October 2017

- ^ Anna M. Cienciala. Obituary. Lawrence Journal-World retrieved 21 October 2017

- ^ New York Times 8 Sept 2017 retrieved 21 October 2017

- ^ Spiegel Online 04.02.2007 retrieved 21 October 2017

- ^ Own website retrieved 21 October 2017

- ^ BBC News, 13 April 2015 retrieved 21 October 2017

- ^ Sports-reference.com retrieved 21 October 2017

- ^ IMDb database retrieved 21 October 2017

- ^ Resonance Publications, March–June 1999 retrieved 21 October 2017

- ^ BBC 2009, The Secret Diary of the Holocaust retrieved 21 October 2017

- ^ Spiegel Online 12.03.2009 retrieved 21 October 2017

- ^ Midwest Center for Holocaust Education retrieved 21 October 2017

- ^ DW.com retrieved 21 October 2017

- ^ Catholic-Hierarchy retrieved 21 October 2017

- ^ Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs retrieved 21 October 2017

- ^ Herald Sun April 28, 2009 retrieved 21 October 2017

- ^ Harvard College, Department of Economics retrieved 21 October 2017

- ^ Sports-reference.com retrieved 21 October 2017

- ^ Israel's Holocaust and the Politics of Nationhood. Cambridge University Press 2005 p. 215 retrieved 21 October 2017

- ^ Knesset website retrieved 21 October 2017

- ^ IMDb retrieved 21 October 2017

- ^ Zdzisław Kuźniar retrieved 11 October 2019

- ^ "Die Freie Stadt Danzig im Überblick". www.gonschior.de.

- ^ Dr. Juergensen, Die freie Stadt Danzig, Danzig: Kafemann, 1925.

- ^ Bacon, Gershon C.; Vivian B. Mann; Joseph Gutmann (1980). Danzig Jewry: A Short History. Jewish Museum (New York). p. 31. ISBN 978-0-8143-1662-7.

- ^ Those congregations in Polish-annexed West Prussia (Pomeranian Voivodeship) merged into the new United Evangelical Church in Poland, which emerged from the old-Prussian Posen ecclesiastical province, with its consistory seated in Poznań.

- ^ In June 1922 the Senate of Danzig and the old-Prussian ecclesiastical executive, the , EOK), concluded a contract to that end. Cf. Adalbert Erler, Die rechtliche Stellung der evangelischen Kirche in Danzig, Berlin: 1929, simultaneously Univ. of Greifswald, Department of Law and Politics, doctor thesis of 21 February 1929, pp. 36 seqq.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Georg May (1981). Ludwig Kaas: der Priester, der Politiker und der Gelehrte aus der Schule von Ulrich Stutz. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 175. ISBN 978-90-6032-197-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Samerski, Stefan; Reimund Haas; Karl Josef Rivinius; Hermann-Josef Scheidgen (2000). Ein aussichtsloses Unternehmen – Die Reaktivierung Bischof Eduard Graf O'Rourkes 1939 (PDF) (in German). Böhlau Verlag Köln Weimar. p. 378. ISBN 978-3-412-04100-7.

- ^ Hans-Jürgen Karp; Joachim Köhler (2001). Katholische Kirche unter nationalsozialistischer und kommunistischer Diktatur: Deutschland und Polen 1939–1989. Böhlau Verlag Köln Weimar. p. 162. ISBN 978-3-412-11800-6.

- ^ Ruhnau, Rüdiger (1971). Danzig: Geschichte einer Deutschen Stadt (in German). Holzner Verlag. p. 94.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Sodeikat, Ernst (1966). "Der Nationalsozialismus und die Danziger Opposition" (PDF) (in German). Institut für Zeitgeschichte. p. 139 ff.

- ^ Grass, Günther; Vivian B. Mann; Joseph Gutmann; Jewish Museum (New York, N.Y.) (1980). Danzig 1939, treasures of a destroyed community. The Jewish Museum, New York. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-8143-1662-7.

- ^ Gdańsk at the Jewish Virtual Library.

- ^ Lemkin, Raphael (2008-06-30). Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. p. 155. ISBN 978-1-58477-901-8.

- ^ (in German) Constitution of Danzig

- ^ Matull, "Ostdeutschlands Arbeiterbewegung", p. 419.

- ^ "Danzig: Übersicht der Wahlen 1919-1935". www.gonschior.de.

- ^ Ratner, Steven R. (1995-02-15). The new UN peacekeeping. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-312-12415-1.

- ^ Sodeikat, p.170, p. 173, Fn.92

- ^ Matull, "Ostdeutschlands Arbeiterbewegung", p. 440, 450.

- ^ Burckhardt, Carl Jakob. Meine Danziger Mission (in German). p. 39.

Lichtenstein, Erwin (1973). Die Juden der Freien Stadt Danzig unter der Herrschaft des Nationalsozialismus (in German). p. 44. - ^ Loew, Peter Oliver (February 2011). Danzig – Biographie einer Stadt (in German). C.H. Beck. p. 206. ISBN 978-3-406-60587-1.

- ^ Loose, Ingo (2007). Kredite für NS-Verbrechen (in German). Institut für Zeitgeschichte. p. 33. ISBN 978-3-486-58331-1.

- ^ Andrzejewski, Marek (1994). Opposition und Widerstand in Danzig (in German). Dietz. p. 99. ISBN 9783801240547.

- ^ Cieslak, Edmund; Biernat, Czeslaw (1995). History of Gdańsk. Fundacji Biblioteki Gdańskiej. p. 454. ISBN 9788386557004.

- ^ Matull, "Ostdeutschlands Arbeiterbewegung", pp. 417, 418.

- ^ Intelligence Service Economic Intelligence Service; Service, Intellige Economic Intelligence (2007-03-01). Commercial Banks 1929–1934. League of Nations. p. LXXXIX. ISBN 978-1-4067-5963-1.

- ^ Ruhnau, Rüdiger (1971). Danzig: Geschichte einer Deutschen Stadt (in German). Holzner Verlag. p. 103.

- ^ Schwartze-Köhler, Hannelore (June 2009). "Die Blechtrommel" von Günter Grass:Bedeutung, Erzähltechnik und Zeitgeschichte (in German). Frank & Timme GmbH. p. 396. ISBN 978-3-86596-237-9.

- ^ Kreutzberger, Max (1970). Leo Baeck Institute New York Bibliothek und Archiv (in German). Mohr Siebeck. p. 67. ISBN 978-3-16-830772-3.

- ^ Bacon, Gershon C. "Danzig Jewry: A Short History". Jewish Virtual Library.

- ^ Grzegorz Berendt (August 2006). "Gdańsk – od niemieckości do polskości" (PDF). Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej IPN (in Polish). Nr. 8–9 (67–68): 53.

- ^ Eleanor Hancock (October 2012). "Ernst Röhm versus General Hans Kundt in Bolivia, 1929—30? The Curious Incident". Journal of Contemporary History. Nr. 4 (47) (4): 695. JSTOR 23488391.

- ^ Hannum, Hurst (2011-10-12). Autonomy, Sovereignty and Self-Determination. University of Pennsylvania. p. 375. ISBN 978-0-8122-1572-4.

- ^ Stahn, Carsten (2008-05-22). The Law and Practice of International Territorial Administration. Cambridge University Press. p. 173 ff, 177. ISBN 978-0-521-87800-5.

- ^ Hutt, Allen (2006-05-30). The Post-War history of the British Working Class. READ BOOKS. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-4067-9826-5.

- ^ Buell, Raymond Leslie (2007-03-31). Poland – Key to Europe. READ BOOKS. p. 159. ISBN 978-1-4067-4564-1.

- ^ Eugene van Cleef, "Danzig and Gdynia," Geographical Review, Vol. 23, No. 1. (Jan., 1933): 106.

- ^ Cieślak, E Biernat, C (1995) History of Gdańsk, Fundacji Biblioteki Gdanskiej. p. 436

- ^ By a decision of the League Council in December 1925, the guard which the Poles were entitled to maintain on this spot [Westerplatte peninsula] was limited to 88 men, though the number might be increased with the consent of the High Commissioner. Geoffrey Malcolm Gathorne-Hardy. A Short History of International Affairs, 1920 to 1934. Royal institute of international affairs (1934). Oxford University Press. p. 384.

- ^ "Mit Gdańska, mit Grassa". www.rp.pl.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wandycz, Piotr Stefan The Twilight of French Eastern Alliances, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988 page 237

- ^ worldcourts.com Archived 2010-12-10 at the Wayback Machine PCIJ, Advisory Opinion No. 11

- ^ worldcourts.com Archived 2013-02-09 at archive.today PCIJ, Advisory Opinion No. 22

- ^ worldcourts.com Archived 2013-02-09 at archive.today PCIJ, Advisory Opinion No. 18

- ^ Lauterpacht, H (1936). International Law Reports 1929–1930. Advisory Opinion No 18: Free City of Danzig and International Labour Organization on August 26, 1930, Collection of Advisory Opinions: Free City of Danzig and International Labour Organization, No. 18 Series B File F (1930). H. Lauterpacht. ISBN 978-0-521-46350-8. Retrieved 2009-08-30.

- ^ Hargreaves, R (2010) Blitzkrieg Unleashed: The German Invasion of Poland, 1939 P31-2

- ^ Epstein, C (2012) Model Nazi: Arthur Greiser and the Occupation of Western Poland, Oxford University Press P58

- ^ Hurst Hannum, p. 377.

- ^ Schlochauer, Hans J.; Krüger, Herbert; Mosler, Hermann (1960-05-01). Wörterbuch des Völkerrechts; Aachener Kongress – Hussar Fall (in German). de Gruyter Verlag. pp. 307, 309. ISBN 978-3-11-001030-5.

- ^ Hiden, John; Lane, Thomas; Prazmowska, Anita J. (1992). The Baltic and the Outbreak of the Second World War. Cambridge University Press. p. 74 ff, 80. ISBN 978-0-521-40467-9.

- ^ Prazmowska, p. 80.

- ^ Prazmowska, p. 81.

- ^ Prazmowska, p. 85.

- ^ Prazmowska, p. 83.

- ^ Wasserstein, Bernard (2007). Barbarism and Civilization. Oxford University Press. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-19-873074-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Prazmowska, Anita "Poland, the 'Danzig Question', and the Outbreak of the Second World War" pages 394-408 from The Origins of the Second World War edited by Frank McDonough, London: Continuum, 2011 page 402.

- ^ Weinberg Gerhard The Foreign Policy of Hitler's Germany : Starting World War II 1937–39, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980 page 560.

- ^ Woodward, E.L., Butler, Rohan, Orde, Anne, editors, Documents on British Foreign Policy 1919–1939, 3rd series, vol.v, HMSO, London, 1952:25

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Prazmowska, Anita "Poland" pages 155-164 from The Origins of The Second World War edited by Robert Boyce and Joseph Maiolo, London: Macmillan, 2003 page 161.

- ^ Weinberg Gerhard The Foreign Policy of Hitler's Germany : Starting World War II 1937–39, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980 page 556.

- ^ Prazmowska, Anita Britain, Poland and the Eastern Front, 1939, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004 pages 90-92.

- ^ Wandycz, Piotr "Poland and the Origins of the Second World War" pages 374-393 from The Origins of the Second World War edited by Frank McDonough, London: Continuum, 2011 page 388.

- ^ Weinberg Gerhard The Foreign Policy of Hitler's Germany : Starting World War II 1937–39, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980 pages 560–562 & 583–584

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Rothwell, Victor The Origins of the Second World War, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001 page 108.

- ^ Weinberg, Gerhard The Foreign Policy of Hitler's Germany Starting World War II University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1980 page 348.

- ^ Prazmowska, Anita "Poland, the 'Danzig Question', and the Outbreak of the Second World War" pages 394-408 from The Origins of the Second World War edited by Frank McDonough, London: Continuum, 2011 page 404.

- ^ Overy, Richard & Wheatcroft, Andrew The Road to War, Random House: London 2009 page 18.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Prazmowska, Anita "Poland, the 'Danzig Question', and the Outbreak of the Second World War" pages 394-408 from The Origins of the Second World War edited by Frank McDonough, London: Continuum, 2011 page 406.

- ^ Prazmowska, Anita "Poland, the 'Danzig Question', and the Outbreak of the Second World War" pages 394-408 from The Origins of the Second World War edited by Frank McDonough, London: Continuum, 2011 page 405.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Rothwell, Victor The Origins of the Second World War, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001 page 161.

- ^ Prazmowska, Anita "Poland" pages 155-164 from The Origins of The Second World War edited by Robert Boyce and Joseph Maiolo, London: Macmillan, 2003 page 163.

- ^ Prazmowska, Anita "Poland, the 'Danzig Question', and the Outbreak of the Second World War" pages 394-408 from The Origins of the Second World War edited by Frank McDonough, London: Continuum, 2011 pages 406-407.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Prazmowska, Anita "Poland, the 'Danzig Question', and the Outbreak of the Second World War" pages 394-408 from The Origins of the Second World War edited by Frank McDonough, London: Continuum, 2011 page 407.

- ^ Watt, D.C. How War Came, London: Heinemann, 1989 page 512.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Watt, D.C. How War Came, London: Heinemann, 1989 page 513.

- ^ Watt, D.C. How War Came, London: Heinemann, 1989 page 484.

- ^ Watt, D.C. How War Came, London: Heinemann, 1989 page 530.

- ^ Bleimeier, John Kuhn (1990-03-01). Hague Yearbook of International Law. Martinus Nijhoff Publ. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-7923-0655-9.

- ^ Dieter Schenk (1995). Die Post von Danzig: Geschichte eines deutschen Justizmords. p. 150. ISBN 978-3-498-06288-0.

- ^ Dieter Schenk, Die Post von Danzig

- ^ [1]

- ^ "Opis jednostki - Służba Więzienna". www.sw.gov.pl.

- ^ Eksterminacyjna i dyskryminacyjna działalność hitlerowskich sądów okręgu Gdańsk-Prusy Zachodnie w latach 1939-1945 "W wyrokach używano często określeń obraźliwych dla Polaków w rodzaju: „polscy podludzie" Edmund Zarzycki Wydawn. Uczelniane WSP, 1981

- ^ The History of Poland Since 1863 By Robert F. Leslie page 281

- ^ Capps, Patrick; Evans, Malcolm David (2003). Asserting Jurisdiction: International and European Legal Perspectives. Hart Publishing. p. 25. ISBN 9781841133058.

- ^ Bykowska, Sylwia (13 May 2018). "Wiosna 1945 - czas, gdy rodził się polski Gdańsk" (in Polish). City of Gdańsk.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bykowska, Sylwia (2005). "Gdańsk – Miasto (Szybko) Odzyskane". Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej (in Polish). 9–10 (56–57): 35–44. ISSN 1641-9561. Archived from the original on 2007-10-22. Retrieved 2009-07-24.

Further reading[]

- Clark, Elizabeth Morrow (1997). "The Free City of Danzig: Borderland, Hansestadt or Social Democracy?". The Polish Review. 42 (3): 259–276. JSTOR 25779004. - Available on JSTOR

- Tadeusz Maciejewski and Maja Maciejewska-Szałas. 2019. "Constitutional Systems of Free European States (1918–1939)." in Modernisation, National Identity and Legal Instrumentalism. Brill.

- Olzewska, Izabela (2013). "Cultural Identity of Citizens of Gdańsk from an Ethnolinguistic Perspective on the Basis of Chosen Texts of the Free City of Danzig". . Institute of Slavic Studies, Polish Academy of Sciences (2): 133–157. doi:10.11649/ch.2013.007. - Polish abstract title: "Tożsamości kulturowa gdańszczan w ujęciu etnolingwistycznym na przykładzie wybranych tekstów publicystycznych Wolnego Miasta Gdańska "

- Stilke, George. "A Short Guide through the Free City of Danzig". - At (Polish: Pomorska Biblioteka Cyfrowa, German: Pommern Digitale Bibliothek, Kashubian: Pòmòrskô Cyfrowô Biblioteka)

External links[]

![]() Media related to Free City of Danzig at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Free City of Danzig at Wikimedia Commons

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Danzig. |

- Extensive Prussian/ Danzig Historical Materials (many in German)

- Map of the Free City

- Jewish community history

- History of Gdańsk / Danzig

- Danzig Online

- Gdańsk history

- Celebration of Gdańsk's centenary in 1997

- History & Hallucination, Wanderlust, Salon.com, January 5, 1998.

- The power of Gdansk at the Wayback Machine (archived September 30, 2007)

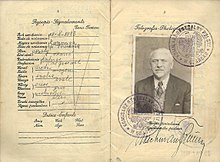

- 1933 Danzig passport, from passportland.com.

- First hand account of growing up in Danzig in the 1930s, a video interview.

- Free City of Danzig

- States and territories established in 1920

- League of Nations mandates

- 1920 establishments in Europe

- 1939 disestablishments in Europe

- Holocaust locations in Poland

- Former polities of the interwar period

- States and territories disestablished in 1939