GIGN

| National Gendarmerie Intervention Group | |

|---|---|

| Groupe d'intervention de la Gendarmerie nationale (French) | |

Official GIGN insignia | |

| Active | March 1974 – present |

| Country | |

| Agency | National Gendarmerie |

| Type | Police tactical unit |

| Role |

|

| Operations jurisdiction |

|

| Headquarters | Satory, Yvelines, France 48°47′6.59″N 2°06′25.80″E / 48.7851639°N 2.1071667°E |

| Motto | "S'engager pour la vie"[1] "A commitment for life" [2] |

| Abbreviation | GIGN |

| Structure | |

| Operators | Approx. 387 |

| Commanders | |

| Current commander | Général de Brigade Ghislain Réty [3] |

| Notable commanders | |

| Notables | |

| Significant operation(s) |

|

| Awards | |

GIGN (Groupe d'intervention de la Gendarmerie nationale ![]() pronunciation (help·info); English: National Gendarmerie Intervention Group) is the elite police tactical unit of the French National Gendarmerie. Its missions include counter-terrorism, hostage rescue, surveillance of national threats, protection of government officials, and targeting organized crime.[4]

pronunciation (help·info); English: National Gendarmerie Intervention Group) is the elite police tactical unit of the French National Gendarmerie. Its missions include counter-terrorism, hostage rescue, surveillance of national threats, protection of government officials, and targeting organized crime.[4]

GIGN was established in 1973 following the Munich massacre. Created initially as a relatively small tactical unit specialized in sensitive hostage situations, it has since grown into a larger force of nearly 400 members,[5] with expanded responsibilities and capabilities. GIGN shares jurisdiction of French territory with the National Police special-response units.[6]

GIGN is headquartered in Versailles-Satory near Paris. Although most of its operations take place in France, the unit, as a component of the French Armed Forces, can operate anywhere in the world. Many of its missions are secret, and members are not allowed to be publicly photographed. Since its formation, GIGN has been involved in over 1,800 missions and rescued more than 600 hostages, making it one of the most experienced counter-terrorism units in the world.[1]

The unit gained notoriety worldwide with its successful assault on a hijacked Air France flight at Marseille Marignane airport in December 1994.

History[]

GIGN was formed in Maisons-Alfort, near Paris, in 1973 in the wake of the Munich massacre and other less well known events in France. Initially named ECRI (Équipe commando régionale d’intervention or Regional Commando Intervention Team), it became operational in March 1974, under the command of then-lieutenant Christian Prouteau and executed its first mission ten days later. Another unit, named GIGN, was created simultaneously within the Mobile Gendarmerie parachute squadron in Mont-de-Marsan in southwest France but the two units were merged under Prouteau's command in 1976 and adopted the GIGN designation.[7] GIGNs initial complement was 15, later increased to 32 in 1976, 78 by 1986, and 120 by 2005.[8] GIGN moved to Versailles-Satory in 1982.

In 1984, it became a part of a larger organisation called GSIGN (Groupement de sécurité et d'intervention de la Gendarmerie nationale), together with EPIGN (Escadron parachutiste d'intervention de la Gendarmerie nationale), the Gendarmerie Parachute Squadron,[9] GSPR (Groupe de sécurité de la présidence de la République), the Presidential Security group and GISA (Groupe d'instruction et de sécurité des activités), a specialized training center.

On 1 September 2007, a major reorganization took place. GSIGN was disbanded and replaced by a new unit also named GIGN. The former GSIGN components (the original GIGN, EPIGN, GSPR and GISA) became "forces" of the new GIGN which now reached a total complement of 380 operators.[10]

The change from GSIGN to the new GIGN, an organization reporting directly to the Director-general of the Gendarmerie, was not a simple name swap. It was done in order to:

- reinforce command and control functions

- provide better integration through common selection, common training and stronger support.

- improve the unit's capability to handle complex situations such as mass hostage-takings similar to the Beslan crisis.[1]

In 2009, the Gendarmerie, while remaining part of the French Armed Forces, was attached to the Ministry of the interior, which already supervised the National Police. The respective areas of responsibility of each force did not change however as the Police already had primary responsibility for major cities and large urban areas while the Gendarmerie was in charge of smaller towns and rural areas (in addition to its specific military missions). Under the new command structure, GIGN gendarmes can still be engaged in military operations outside of France due to their military status.

Coordination between GIGN and RAID, the national police elite team, is handled by a joint organization called Ucofi (Unité de coordination des forces d’intervention Intervention forces coordination unit). A "leader/follower" protocol has been established for use when both units need to be engaged jointly,[11] leadership belonging to the unit operating in its primary areas of responsibility.[12]

Since its creation, the group has taken part in over 1800 operations, liberated over 600 hostages and arrested over 1500 suspects,[1] losing two members killed in action and seven in training. The two fatalities in action were sustained when dealing with armed deranged persons.

On 9 December 2011, French Defense Minister[13] Gérard Longuet, awarded the Cross for Military Valour to the unit for its participation in operation Harmattan in Libya.[14]

On 31 July 2013, the unit won a second Cross for Military Valour for its participation in the Afghanistan War (2001-).[15]

In January 2015, GIGN was engaged for the very first time simultaneously with RAID, the national Police tactical unit, during the January 2015 Île-de-France attacks.[16]

On 15 June 2015, the unit received the Medal for internal security. As GIGN was awarded twice the Cross for Military Valour, members of the group are officially allowed to wear the Fourragère.[17]

Missions[]

- Counter-terrorism.

- Hostage rescue.

- Arrest of dangerous or deranged armed persons.

- Resolution of prison riots.

- Surveillance and observation of criminals and terrorists.

- Military special operations.

- Protection of officials.

- Critical site protection (embassies in war torn countries).

- Training.

- Hostage rescue demo during the Eurosatory 2018 trade fair

Assault team with attack dog and Centigon Armoured SUV

GIGN operators and attack dog

GIGN operators forming an assault column

- Force Sécurité Protection (FSP) demo - Satory, September 2018

VIP vehicle is ambushed

FSP gendarmes shoot back

FSP gendarmes extract the VIP from his vehicle and escort him to theirs

- Force Sécurité Protection (FSP) demo - Satory, September 2018

The convoy leaves the ambush area

The lead car rams a car barricade

The convoy safely escapes

Structure[]

GIGN is currently organized in six "forces", under two headquarters (administrative and operational):[18]

- Intervention force (French: Force Intervention (FI) – the original GIGN): approx. 100 men, serving as GIGN's main assault unit. It is divided into four platoons (French: sections), two of which are on permanent alert. These platoons are further divided into individual teams of operators. Two of the intervention platoons are specialized in high altitude jumps, the other two are specialized in diving.

- Observation & search force (French: Force Observation/Recherche (FOR) – from the former EPIGN): approx. 40 men & women, specializing in reconnaissance work in relation with judiciary police work, and counter-terrorism.

- Security & protection force (French: Force Sécurité/Protection (FSP) – from the former EPIGN and GSPR): approx. 65 men & women, specializing in executive and sensitive site protection.

- The Gendarmerie detachment of the GSPR Presidential Security Group (French: Détachement GSPR): GSPR was originally a Gendarmerie unit, it is now a joint Police-Gendarmerie unit. Their main mission is the close protection of the French president.

- Operational Support force (French: Force Appui opérationnel (FAO): support force with specialized cells (long range sniping, breaching, assault engineering, special devices etc.)

- Training force (French: Force Formation (FF): this force is tasked with selection, training and retraining (called recycling) not only of GIGN operators, but also of selected Gendarmerie or foreign personnel.

Female gendarmes are admitted in all forces, except the intervention force.

There are several tactical specialties in the group, including: long-range sniping, breaching, observation and reconnaissance, executive protection, free fall parachuting with HALO/HAHO jumps, diving, etc.

Helicopter support is provided by Gendarmerie helicopters and, for tactical deployment of large groups, by GIH (French: Groupe interarmées d'hélicoptères) a joint army/air force special operations flight equipped with SA330 PUMA helicopters based in nearby Villacoublay air base. GIH was established in 2006 and has also been tasked to support the National Police RAID unit since 2008.

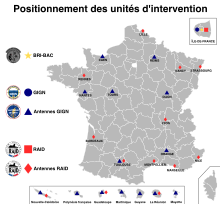

Fourteen regional units called "GIGN branches" (French: Antennes du GIGN) [19] manned by personnel selected and trained by GIGN, complement its action in metropolitan France and in the French overseas departments and territories. The domestic antennes, initially known as PI2Gs (French: Pelotons d'intervention interrégionaux de la Gendarmerie) have been redesignated as GIGN branches in April 2016; the overseas antennes initially known as GPIs (French: Groupes de pelotons d'intervention) were in turn redesignated as GIGN branches on 26 July 2016.[20] As of 2021, the seven metropolitan GIGN branches are located in Caen, Dijon, Nantes, Orange, Reims, Toulouse and Tours while the seven overseas branches are based in Guadeloupe, Martinique, French Guiana, Réunion, Mayotte, French Polynesia and New Caledonia. The twenty nuclear protection units called PSPGs (French: Pelotons spécialisés de protection de la Gendarmerie - Gendarmerie specialized protection platoons), located on site at each one of the French nuclear power plants, are not a part of GIGN but operate under its supervision.

Operations[]

GIGN reports directly to the Director general of the Gendarmerie Nationale (DGGN) i.e. the chief of staff of the Gendarmerie who in turn reports directly to the Ministry of the interior. The DGGN can take charge in a major crisis; however, most of the day-to-day missions are conducted in support of local units of the Departmental Gendarmerie. GIGN is also a member of the European ATLAS Network, an informal association consisting of the special police units of the 27 states of the European Union.

Some of the best known GIGN operations include:

- The liberation of 30 French pupils from a school bus captured by the FLCS (Front de Libération de la Côte des Somalis, "Somali Coast Liberation Front") in Loyada, near Djibouti in 1976. GIGN snipers and French Foreign Legion troops neutralized the hostage takers in an operation that was only partially successful as two children were killed.

- Planning the liberation of diplomats from the French embassy in San Salvador in 1979 (the hostage-takers surrendered before the assault was conducted).

- Advising Saudi authorities on regaining control during the Grand Mosque Seizure in Mecca, Saudi Arabia in November and December 1979.

- Arrest of several Corsican terrorists of the National Liberation Front of Corsica in Fesch Hostel in 1980.

- The controversial arrest of suspected Irish terrorists in the Irish of Vincennes affair in August 1982.

- The controversial liberation of hostages of the Ouvéa cave hostage taking in Ouvea, New Caledonia, in May 1988.

- Protection of the 1992 Olympic Winter Games in Albertville.

- Liberation of 229 passengers and crew from Air France Flight 8969 in Marseille in December 1994. The airliner had been hijacked by four GIA terrorists who were shot during the assault. Three passengers had been executed during the negotiations with the Algerian government before the plane was allowed to leave Algiers, but the assault resulted in no further loss of life for the passengers and crew, at the cost of 25 persons wounded (13 passengers, 3 aircrew and 9 GIGN). The mission received a wide coverage as news channels broadcast the assault live.

- Arrest of the mercenary Bob Denard and his group during a coup attempt in 1995 in Comoros (Operation Azalee).

- Operations in Bosnia to arrest persons indicted for war crimes.

- Capture of 6 Somali pirates and recovery of part of the ransom after ensuring that Le Ponant luxury yacht hostages were freed in the coast of Puntland in Somalia on the Gulf of Aden. In conjunction with French Commandos Marine in April 2008.

- Deployment of tactical teams in Afghanistan in support of French Gendarmerie POMLT (Police Operational Mentoring Liaison Team) detachments 2009-2011.

- 2011 : Deployment in Libya during Operation Harmattan.[14]

- Neutralization of the two terrorists involved in the Paris Charlie Hebdo shooting in January 2015.

- Deployment following an Al-Qaeda hostage situation at the Radisson Blu hotel in Bamako, Mali on November 20, 2015, (but the situation had already been taken care of by local police with assistance from US and French special forces when the GIGN team arrived).

- Neutralization of the terrorist responsible for the Carcassonne and Trèbes attack in March 2018 (a former EPIGN officer, Arnaud Beltrame, voluntarily swapped places with a hostage and was killed trying to disarm the terrorist). This operation was in fact conducted by a regional unit (one of six metropolitan-based GIGN branches or Antennes du GIGN), based in Toulouse, under GIGN supervision, while operatives sent from Satory were still underway.

GIGN was selected by the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) to teach the special forces of the other member states in hostage-rescue exercises aboard planes.

Selection and training[]

Candidates undertake a one-week pre-selection screening followed, for those accepted, by a fourteen months training program which includes shooting, long-range marksmanship (it is often considered[by whom?] as one of the best shooting schools in the world), an airborne course and hand-to-hand combat training.[1] Mental ability and self-control are important in addition to physical strength. Like for most special forces, the training is stressful with a high washout rate, especially in the initial phase – only 7–8% of volunteers make it through the training process.

- Weapons handling

- Combat shooting and marksmanship training

- Airborne courses, such as HALO or HAHO jumps, paragliding, and heli-borne insertions

- Combat/Underwater swimming, diving and assault of ships

- Hand-to-hand combat training

- Undercover surveillance and stalking (support in investigating cases)

- Infiltration and escape techniques

- Explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) and CBRN devices neutralization

- Survival and warfare in tropical, arctic, mountain and desert environments

- Diplomacy skills, such as negotiating

Equipment and weapons[]

GIGN is equipped with a wide range of police and military equipment that includes :

- Sidearms:

- Pistols: Glock (mainly 17/19/26 series) and SIG Sauer (SP 2022),

- Revolvers: Manurhin MR 73 and Smith & Wesson (Model 686),

- Submachine Guns: MP5, MP7, and FN P90

- Shotguns: Remington, Franchi, Benelli,

- Assault Rifles: Heckler & Koch (HK 416, HK 417, G36), Swiss Arms (SG 550, SG 551, SG 552) and, since 2017 : CZ BREN 2 chambered in 7.62×39mm.[21] The FAMAS also has ceremonial use.

- Sniper Rifles: Accuracy International Arctic Warfare rifle chambered in .308 and .338, and PGM Hécate II rifle chambered in 12.7x99mm.

- Various types of armored vehicle such as the Sherpa Light and Chevrolet Swatec HARAS (Height adjustable rescue assault system) assault ladders and Centigon Fortress Intervention armored SUV.

- Weapons

A MR 73 Manurhin revolver is traditionally issued to each GIGN operator

GIGN version of the CZ BREN 2

MR73 revolver with 8" barrel and Bushnell Phantom scope

- Vehicles

Chevrolet Swatec Haras assault ladder

Centigon armored vehicle

Renault Truck Defense Sherpa armored assault ladder

Motto and values[]

- Until 2014: Sauver des vies au mépris de la sienne ("To save lives without regard to one's own")

- Since 2014: S'engager pour la vie[1] ("A commitment for life"[2])

Although GIGN is part of the French military and has been deployed to external combat zones, it is primarily centered in France, engaging in peacetime operations as a special police force. Respect of human life and fire discipline have always been taught to group members since inception, and each new member is traditionally issued with a 6 shot .357 revolver as a reminder of these values.[1][22]

GIGN leaders[]

- Chef d'escadron (major) Christian Prouteau: 1973–1982

- Capitaine (captain) Paul Barril: 1982–1983 (Interim)

- Capitaine (captain) Philippe Masselin: 1983–1985

- Chef d'escadron (major) Philippe Legorjus: 1985–1989

- Chef d'escadron (major) Lionel Chesneau: 1989–1992

- Chef d'escadron (major) Denis Favier: 1992–1997

- Chef d'escadron (major) Eric Gerard: 1997–2002

- Lieutenant-Colonel Frédéric Gallois: 2002-2007

- Général de Brigade Denis Favier: 2007–2011

- Général de Brigade Thierry Orosco: 2011–2014

- Général de Brigade Hubert Bonneau: 2014–2017

- Général de Brigade Laurent Phélip: 2017–2020 [23]

- Général de Brigade Ghislain Réty: since August 2020 [3]

In popular culture[]

GIGN is featured in the following films :

- L'Assaut, a 2010 French film about the Air France Flight 8969 hijacking. It was done with the collaboration and the advice of the unit. There are a few fictional personal stories intertwined with the action (mainly where female characters are involved) but otherwise, the film matches the numerous accounts that have been made by the real participants in this action.

- L'Ordre et la Morale (Rebellion) a film released in 2011 about the controversial 1988 Ouvéa cave hostage taking in New Caledonia as seen from the perspective of then GIGN leader, major (then a captain) Philippe Legorjus. Even though he had played a major role in the negotiations and he participated in the first part of the assault, Legorgus's leadership during and after the action was contested - even in his own unit - and he left GIGN a few months later.

See also[]

- Law enforcement in France

- Counter-terrorism

- List of police tactical units

- ATLAS Network

- National Liberation Front of Corsica

- RAID

- Research and Intervention Brigade

- GSG 9

- Hostage Rescue Team

References[]

Footnotes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Gend'info magazine (Official Gendarmerie information magazine in French). GIGNs 40th anniversary issue. December 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b S'engager in French can mean to commit (to do something) but also to enlist (in the army)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Journal Officiel de la République française (JORF). Décret du 31 juillet 2020 portant affectations d'officiers généraux https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000042197458

- ^ Peachy, Paul. "Who are GIGN? Elite police force formed after 1972 Olympics attack on Israelis". The Independent. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ circa 570 with the regional branches.

- ^ Each of the two French national police forces, the National Police and the National Gendarmerie, has primary responsibility for a part of the territory: large cities and urban areas for the National Police, smaller cities and rural areas for the National Gendarmerie. There are two National Police units specialized in counter-terrorism and hostage rescue: the Paris Research and Intervention Brigade and RAID. If needed, they can form a joint task force called National Police Intervention Force (French: Force d'intervention de la Police nationale or FIPN). GIGN and FIPN (or its components) can be engaged together – or in the other force's area of responsibility – in an emergency.

- ^ From 1974 to 1976, the Maisons-Alfort unit was named GIGN 1 and the Mont-de-Marsan unit GIGN 4. Histoire de la gendarmerie mobile d'Ile-de-France, 3 volumes, Éditions SPE-Barthelemy, Paris, 2007, ISBN 2-912838-31-2 — tome II

- ^ Encyclopédie de la Gendarmerie Nationale, tome III

- ^ Squadron in the British sense of the term. The equivalent US unit would be a troop or a company.

- ^ The reorganization was conducted by general Denis Favier, who had personally led the Marignane assault in 1994 as GIGN's commander and assumed command of the "new" GIGN in 2007. He later became Director-general of the Gendarmerie Nationale (DGGN) from 2013 to 2016.

- ^ As was the case following the January 2015 Charlie Hebdo assassinations.

- ^ Colonel Bonneau interview, L’Essor de la Gendarmerie nationale n°478 – February 2015 issue.

- ^ The title was changed in 2017 to Ministre des Armées ('Minister of the Armies')

- ^ Jump up to: a b https://www.gendarmerie.interieur.gouv.fr/gign/Actus/La-croix-de-la-Valeur-militaire-pour-le-GIGN

- ^ nationale, Gendarmerie. "Remise de la seconde Croix de la Valeur militaire au GIGN". Gendarmerie (in French). Retrieved 2019-07-06.

- ^ The two actions were distinct but coordinated

- ^ nationale, Gendarmerie. "Le drapeau du GIGN reçoit la fourragère et la médaille de la sécurité intérieure". Gendarmerie (in French). Retrieved 2019-07-06.

- ^ Le GIGN par le GIGN (in French), 2012 p. 9

- ^ https://www.ouest-france.fr/normandie/caen-14000/le-gign-officialise-son-arrivee-a-caen-7142912

- ^ Gendarmerie memorandum 61050 dated 26 July 2016.

- ^ http://www.gign-historique.com/gign/le-gign-sequipe-dun-nouveau-fusil-dassaut-bren-2-tcheque/

- ^ Rogoway, Tyler (17 December 2018). "France's Elite GIGN Counter Terror Unit Still Has A Cult-Like Affinity For The Revolver". The Warzone. The Drive. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ^ Promotion to brigadier general on August, 1st 2018 - https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do;jsessionid=287069C58D39A0AEA6A9AEE966E3AC8D.tplgfr21s_3?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000037257874&dateTexte=&oldAction=rechJO&categorieLien=id&idJO=JORFCONT000037257534

Bibliography[]

- Collective (2012). Le GIGN par le GIGN (in French). éditions LBM. ISBN 978-2-9153-4794-4.

- Collective (2006). Encyclopédie de la Gendarmerie Nationale, tome III (in French). Paris: éditions SPE Barthelemy. ISBN 2-912838-21-5.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to National Gendarmerie Intervention Group. |

- 1973 establishments in France

- Counter-terrorist organizations

- French Gendarmerie

- Specialist law enforcement agencies of France

- ATLAS Network