Geometric series

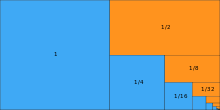

In mathematics, a geometric series is the sum of an infinite number of terms that have a constant ratio between successive terms. For example, the series

is geometric, because each successive term can be obtained by multiplying the previous term by 1/2. In general, a geometric series is written as a + ar + ar2 + ar3 + ... , where a is the coefficient of each term and r is the common ratio between adjacent terms. Geometric series are among the simplest examples of infinite series and can serve as a basic introduction to Taylor series and Fourier series. Geometric series had an important role in the early development of calculus, are used throughout mathematics, and have important applications in physics, engineering, biology, economics, computer science, queueing theory, and finance.

The distinction between a progression and a series is that a progression is a sequence, whereas a series is a sum.

Coefficient a[]

The geometric series a + ar + ar2 + ar3 + ... is written in expanded form.[1] Every coefficient in the geometric series is the same. In contrast, the power series written as a0 + a1r + a2r2 + a3r3 + ... in expanded form has coefficients ai that can vary from term to term. In other words, the geometric series is a special case of the power series. The first term of a geometric series in expanded form is the coefficient a of that geometric series.

In addition to the expanded form of the geometric series, there is a generator form[1] of the geometric series written as

- ark

and a closed form of the geometric series written as

- a / (1 - r) within the range |r| < 1.

The derivation of the closed form from the expanded form is shown in this article's Sum section. The derivation requires that all the coefficients of the series be the same (coefficient a) in order to take advantage of self-similarity and to reduce the infinite number of additions and power operations in the expanded form to the single subtraction and single division in the closed form. However even without that derivation, the result can be confirmed with long division: a divided by (1 - r) results in a + ar + ar2 + ar3 + ... , which is the expanded form of the geometric series.

Typically a geometric series is thought of as a sum of numbers a + ar + ar2 + ar3 + ... but can also be thought of as a sum of functions a + ar + ar2 + ar3 + ... that converges to the function a / (1 - r) within the range |r| < 1. The adjacent image shows the contribution each of the first nine terms (i.e., functions) make to the function a / (1 - r) within the range |r| < 1 when a = 1. Changing even one of the coefficients to something other than coefficient a would (in addition to changing the geometric series to a power series) change the resulting sum of functions to some function other than a / (1 - r) within the range |r| < 1. As an aside, a particularly useful change to the coefficients is defined by the Taylor series, which describes how to change the coefficients so that the sum of functions converges to any user selected, sufficiently smooth function within a range.

Common ratio r[]

The geometric series a + ar + ar2 + ar3 + ... is an infinite series defined by just two parameters: coefficient a and common ratio r. Common ratio r is the ratio of any term with the previous term in the series. Or equivalently, common ratio r is the term multiplier used to calculate the next term in the series. The following table shows several geometric series:

| a | r | Example series |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | 10 | 4 + 40 + 400 + 4000 + 40,000 + ··· |

| 3 | 1 | 3 + 3 + 3 + 3 + 3 + ··· |

| 1 | 2/3 | 1 + 2/3 + 4/9 + 8/27 + 16/81 + ··· |

| 1/2 | 1/2 | 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/16 + 1/32 + ··· |

| 9 | 1/3 | 9 + 3 + 1 + 1/3 + 1/9 + ··· |

| 7 | 1/10 | 7 + 0.7 + 0.07 + 0.007 + 0.0007 + ··· |

| 1 | −1/2 | 1 − 1/2 + 1/4 − 1/8 + 1/16 − 1/32 + ··· |

| 3 | −1 | 3 − 3 + 3 − 3 + 3 − ··· |

The convergence of the geometric series depends on the value of the common ratio r:

- If |r| < 1, the terms of the series approach zero in the limit (becoming smaller and smaller in magnitude), and the series converges to the sum a / (1 - r).

- If |r| = 1, the series does not converge. When r = 1, all of the terms of the series are the same and the series is infinite. When r = −1, the terms take two values alternately (for example, 2, −2, 2, −2, 2,... ). The sum of the terms oscillates between two values (for example, 2, 0, 2, 0, 2,... ). This is a different type of divergence. See for example Grandi's series: 1 − 1 + 1 − 1 + ···.

- If |r| > 1, the terms of the series become larger and larger in magnitude. The sum of the terms also gets larger and larger, and the series does not converge to a sum. (The series diverges.)

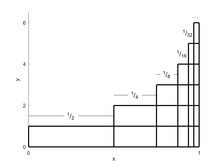

The rate of convergence also depends on the value of the common ratio r. Specifically, the rate of convergence gets slower as r approaches 1 or −1. For example, the geometric series with a = 1 is 1 + r + r2 + r3 + ... and converges to 1 / (1 - r) when |r| < 1. However, the number of terms needed to converge approaches infinity as r approaches 1 because a / (1 - r) approaches infinity and each term of the series is less than or equal to one. In contrast, as r approaches −1 the sum of the first several terms of the geometric series starts to converge to 1/2 but slightly flips up or down depending on whether the most recently added term has a power of r that is even or odd. That flipping behavior near r = −1 is illustrated in the adjacent image showing the first 11 terms of the geometric series with a = 1 and |r| < 1.

The common ratio r and the coefficient a also define the geometric progression, which is a list of the terms of the geometric series but without the additions. Therefore the geometric series a + ar + ar2 + ar3 + ... has the geometric progression (also called the geometric sequence) a, ar, ar2, ar3, ... The geometric progression - as simple as it is - models a surprising number of natural phenomena,

- from some of the largest observations such as the expansion of the universe where the common ratio r is defined by Hubble's constant,

- to some of the smallest observations such as the decay of radioactive carbon-14 atoms where the common ratio r is defined by the half-life of carbon-14.

As an aside, the common ratio r can be a complex number such as |r|eiθ where |r| is the vector's magnitude (or length), θ is the vector's angle (or orientation) in the complex plane and i2 = -1. With a common ratio |r|eiθ, the expanded form of the geometric series is a + a|r|eiθ + a|r|2ei2θ + a|r|3ei3θ + ... Modeling the angle θ as linearly increasing over time at the rate of some angular frequency ω0 (in other words, making the substitution θ = ω0t), the expanded form of the geometric series becomes a + a|r|eiω0t + a|r|2ei2ω0t + a|r|3ei3ω0t + ... , where the first term is a vector of length a not rotating at all, and all the other terms are vectors of different lengths rotating at harmonics of the fundamental angular frequency ω0. The constraint |r|<1 is enough to coordinate this infinite number of vectors of different lengths all rotating at different speeds into tracing a circle, as shown in the adjacent video. Similar to how the Taylor series describes how to change the coefficients so the series converges to a user selected sufficiently smooth function within a range, the Fourier series describes how to change the coefficients (which can also be complex numbers in order to specify the initial angles of vectors) so the series converges to a user selected periodic function.

Sum[]

Closed-form formula[]

For , the sum of the first n+1 terms of a geometric series, up to and including the r n term, is

where r is the common ratio. One can derive that closed-form formula for the partial sum, s, by subtracting out the many self-similar terms as follows:[2][3][4]

As n approaches infinity, the absolute value of r must be less than one for the series to converge. The sum then becomes

When a = 1, this can be simplified to

The formula also holds for complex r, with the corresponding restriction, the modulus of r is strictly less than one.

As an aside, the question of whether an infinite series converges is fundamentally a question about the distance between two values: given enough terms, does the value of the partial sum get arbitrarily close to the value it is approaching? In the above derivation of the closed form of the geometric series, the interpretation of the distance between two values is the distance between their locations on the number line. That is the most common interpretation of distance between two values. However the p-adic metric, which has become a critical notion in modern number theory, offers a definition of distance such that the geometric series 1 + 2 + 4 + 8 + ... with a = 1 and r = 2 actually does converge to a / (1 - r) = 1 / (1 - 2) = -1 even though r is outside the typical convergence range |r| < 1.

Proof of convergence[]

We can prove that the geometric series converges using the sum formula for a geometric progression:

The second equality is true because if then as and

Convergence of geometric series can also be demonstrated by rewriting the series as an equivalent telescoping series. Consider the function,

Note that

Thus,

If

then

So S converges to

Rate of convergence[]

As shown in the above proofs, the closed form of the geometric series partial sum up to and including the n-th power of r is a(1 - rn+1) / (1 - r) for any value of r, and the closed form of the geometric series is the full sum a / (1 - r) within the range |r| < 1.

If the common ratio is within the range 0 < r < 1, then the partial sum a(1 - rn+1) / (1 - r) increases with each added term and eventually gets within some small error, E, ratio of the full sum a / (1 - r). Solving for n at that error threshold,

where 0 < r < 1, the ceiling operation constrains n to integers, and dividing both sides by the natural log of r flips the inequality because it is negative. The result n+1 is the number of partial sum terms needed to get within aE / (1 - r) of the full sum a / (1 - r). For example to get within 1% of the full sum a / (1 - r) at r=0.1, only 2 (= ln(E) / ln(r) = ln(0.01) / ln(0.1)) terms of the partial sum are needed. However at r=0.9, 44 (= ln(0.01) / ln(0.9)) terms of the partial sum are needed to get within 1% of the full sum a / (1 - r).

If the common ratio is within the range -1 < r < 0, then the geometric series is an alternating series but can be converted into the form of a non-alternating geometric series by combining pairs of terms and then analyzing the rate of convergence using the same approach as shown for the common ratio range 0 < r < 1. Specifically, the partial sum

- s = a + ar + ar2 + ar3 + ar4 + ar5 + ... + arn-1 + arn within the range -1 < r < 0 is equivalent to

- s = a - ap + ap2 - ap3 + ap4 - ap5 + ... + apn-1 - apn with an n that is odd, with the substitution of p = -r, and within the range 0 < p < 1,

- s = (a - ap) + (ap2 - ap3) + (ap4 - ap5) + ... + (apn-1 - apn) with adjacent and differently signed terms paired together,

- s = a(1 - p) + a(1 - p)p2 + a(1 - p)p4 + ... + a(1 - p)p2(n-1)/2 with a(1 - p) factored out of each term,

- s = a(1 - p) + a(1 - p)p2 + a(1 - p)p4 + ... + a(1 - p)p2m with the substitution m = (n - 1) / 2 which is an integer given the constraint that n is odd,

which is now in the form of the first m terms of a geometric series with coefficient a(1 - p) and with common ratio p2. Therefore the closed form of the partial sum is a(1 - p)(1 - p2(m+1)) / (1 - p2) which increases with each added term and eventually gets within some small error, E, ratio of the full sum a(1 - p) / (1 - p2). As before, solving for m at that error threshold,

where 0 < p < 1 or equivalently -1 < r < 0, and the m+1 result is the number of partial sum pairs of terms needed to get within a(1 - p)E / (1 - p2) of the full sum a(1 - p) / (1 - p2). For example to get within 1% of the full sum a(1 - p) / (1 - p2) at p=0.1 or equivalently r=-0.1, only 1 (= ln(E) / (2 ln(p)) = ln(0.01) / (2 ln(0.1)) pair of terms of the partial sum are needed. However at p=0.9 or equivalently r=-0.9, 22 (= ln(0.01) / (2 ln(0.9))) pairs of terms of the partial sum are needed to get within 1% of the full sum a(1 - p) / (1 - p2). Comparing the rate of convergence for positive and negative values of r, n + 1 (the number of terms required to reach the error threshold for some positive r) is always twice as large as m + 1 (the number of term pairs required to reach the error threshold for the negative of that r) but the m + 1 refers to term pairs instead of single terms. Therefore, the rate of convergence is symmetric about r = 0, which can be a surprise given the asymmetry of a / (1 - r). One perspective that helps explain this rate of convergence symmetry is that on the r > 0 side each added term of the partial sum makes a finite contribution to the infinite sum at r = 1 while on the r < 0 side each added term makes a finite contribution to the infinite slope at r = -1.

As an aside, this type of rate of convergence analysis is particularly useful when calculating the number of Taylor series terms needed to adequately approximate some user-selected sufficiently-smooth function or when calculating the number of Fourier series terms needed to adequately approximate some user-selected periodic function.

Historic insights[]

Zeno of Elea (c.495 – c.430 BC)[]

2,500 years ago, Greek mathematicians had a problem with walking from one place to another. Physically, they were able to walk as well as we do today, perhaps better. Logically, however, they thought[5] that an infinitely long list of numbers greater than zero summed to infinity. Therefore, it was a paradox when Zeno of Elea pointed out that in order to walk from one place to another, you first have to walk half the distance, and then you have to walk half the remaining distance, and then you have to walk half of that remaining distance, and you continue halving the remaining distances an infinite number of times because no matter how small the remaining distance is you still have to walk the first half of it. Thus, Zeno of Elea transformed a short distance into an infinitely long list of halved remaining distances, all of which are greater than zero. And that was the problem: how can a distance be short when measured directly and also infinite when summed over its infinite list of halved remainders? The paradox revealed something was wrong with the assumption that an infinitely long list of numbers greater than zero summed to infinity.

Euclid of Alexandria (c.300 BC)[]

Euclid's Elements of Geometry[6] Book IX, Proposition 35, proof (of the proposition in adjacent diagram's caption):

Let AA', BC, DD', EF be any multitude whatsoever of continuously proportional numbers, beginning from the least AA'. And let BG and FH, each equal to AA', have been subtracted from BC and EF. I say that as GC is to AA', so EH is to AA', BC, DD'.

For let FK be made equal to BC, and FL to DD'. And since FK is equal to BC, of which FH is equal to BG, the remainder HK is thus equal to the remainder GC. And since as EF is to DD', so DD' to BC, and BC to AA' [Prop. 7.13], and DD' equal to FL, and BC to FK, and AA' to FH, thus as EF is to FL, so LF to FK, and FK to FH. By separation, as EL to LF, so LK to FK, and KH to FH [Props. 7.11, 7.13]. And thus as one of the leading is to one of the following, so (the sum of) all of the leading to (the sum of) all of the following [Prop. 7.12]. Thus, as KH is to FH, so EL, LK, KH to LF, FK, HF. And KH equal to CG, and FH to AA', and LF, FK, HF to DD', BC, AA'. Thus, as CG is to AA', so EH to DD', BC, AA'. Thus, as the excess of the second is to the first, so is the excess of the last is to all those before it. The very thing it was required to show.

The terseness of Euclid's propositions and proofs may have been a necessity. As is, the Elements of Geometry is over 500 pages of propositions and proofs. Making copies of this popular textbook was labor intensive given that the printing press was not invented until 1440. And the book's popularity lasted a long time: as stated in the cited introduction to an English translation, Elements of Geometry "has the distinction of being the world's oldest continuously used mathematical textbook." So being very terse was being very practical. The proof of Proposition 35 in Book IX could have been even more compact if Euclid could have somehow avoided explicitly equating lengths of specific line segments from different terms in the series. For example, the contemporary notation for geometric series (i.e., a + ar + ar2 + ar3 + ... + arn) does not label specific portions of terms that are equal to each other.

Also in the cited introduction the editor comments,

Most of the theorems appearing in the Elements were not discovered by Euclid himself, but were the work of earlier Greek mathematicians such as Pythagoras (and his school), Hippocrates of Chios, Theaetetus of Athens, and Eudoxus of Cnidos. However, Euclid is generally credited with arranging these theorems in a logical manner, so as to demonstrate (admittedly, not always with the rigour demanded by modern mathematics) that they necessarily follow from five simple axioms. Euclid is also credited with devising a number of particularly ingenious proofs of previously discovered theorems (e.g., Theorem 48 in Book 1).

To help translate the proposition and proof into a form that uses current notation, a couple modifications are in the diagram. First, the four horizontal line lengths representing the values of the first four terms of a geometric series are now labeled a, ar, ar2, ar3 in the diagram's left margin. Second, new labels A' and D' are now on the first and third lines so that all the diagram's line segment names consistently specify the segment's starting point and ending point.

Here is a phrase by phrase interpretation of the proposition:

| Proposition | in contemporary notation |

|---|---|

| "If there is any multitude whatsoever of continually proportional numbers" | Taking the first n+1 terms of a geometric series Sn = a + ar + ar2 + ar3 + ... + arn |

| "and equal to the first is subtracted from the second and the last" | and subtracting a from ar and arn |

| "then as the excess of the second to the first, so the excess of the last will be to all those before it." | then (ar-a) / a = (arn-a) / (a + ar + ar2 + ar3 + ... + arn-1) = (arn-a) / Sn-1, which can be rearranged to the more familiar form Sn-1 = a(rn-1) / (r-1). |

Similarly, here is a sentence by sentence interpretation of the proof:

| Proof | in contemporary notation |

|---|---|

| "Let AA', BC, DD', EF be any multitude whatsoever of continuously proportional numbers, beginning from the least AA'." | Consider the first n+1 terms of a geometric series Sn = a + ar + ar2 + ar3 + ... + arn for the case r>1 and n=3. |

| "And let BG and FH, each equal to AA', have been subtracted from BC and EF." | Subtract a from ar and ar3. |

| "I say that as GC is to AA', so EH is to AA', BC, DD'." | I say that (ar-a) / a = (ar3-a) / (a + ar + ar2). |

| "For let FK be made equal to BC, and FL to DD'." | |

| "And since FK is equal to BC, of which FH is equal to BG, the remainder HK is thus equal to the remainder GC." | |

| "And since as EF is to DD', so DD' to BC, and BC to AA' [Prop. 7.13], and DD' equal to FL, and BC to FK, and AA' to FH, thus as EF is to FL, so LF to FK, and FK to FH." | |

| "By separation, as EL to LF, so LK to FK, and KH to FH [Props. 7.11, 7.13]." | By separation, (ar3-ar2) / ar2 = (ar2-ar) / ar = (ar-a) / a = r-1. |

| "And thus as one of the leading is to one of the following, so (the sum of) all of the leading to (the sum of) all of the following [Prop. 7.12]." | The sum of those numerators and the sum of those denominators form the same proportion: ((ar3-ar2) + (ar2-ar) + (ar-a)) / (ar2 + ar + a) = r-1. |

| "And thus as one of the leading is to one of the following, so (the sum of) all of the leading to (the sum of) all of the following [Prop. 7.12]." | And this sum of equal proportions can be extended beyond (ar3-ar2) / ar2 to include all the proportions up to (arn-arn-1) / arn-1. |

| "Thus, as KH is to FH, so EL, LK, KH to LF, FK, HF." | |

| "And KH equal to CG, and FH to AA', and LF, FK, HF to DD', BC, AA'." | |

| "Thus, as CG is to AA', so EH to DD', BC, AA'." | |

| "Thus, as the excess of the second is to the first, so is the excess of the last is to all those before it." | Thus, (ar-a) / a = (ar3-a) / S2. Or more generally, (ar-a) / a = (arn-a) / Sn-1, which can be rearranged in the more common form Sn-1 = a(rn-1) / (r-1). |

| "The very thing it was required to show." | Q.E.D. |

Archimedes of Syracuse (c. 287 – c. 212 BC)[]

Archimedes used the sum of a geometric series to compute the area enclosed by a parabola and a straight line. His method was to dissect the area into an infinite number of triangles.

Archimedes' Theorem states that the total area under the parabola is 4/3 of the area of the blue triangle.

Archimedes determined that each green triangle has 1/8 the area of the blue triangle, each yellow triangle has 1/8 the area of a green triangle, and so forth.

Assuming that the blue triangle has area 1, the total area is an infinite sum:

The first term represents the area of the blue triangle, the second term the areas of the two green triangles, the third term the areas of the four yellow triangles, and so on. Simplifying the fractions gives

This is a geometric series with common ratio 1/4 and the fractional part is equal to

The sum is

This computation uses the method of exhaustion, an early version of integration. Using calculus, the same area could be found by a definite integral.

Nicole Oresme (c.1323 – 1382)[]

Among his insights into infinite series, in addition to his elegantly simple proof of the divergence of the harmonic series, Nicole Oresme[7] proved that the series 1/2 + 2/4 + 3/8 + 4/16 + 5/32 + 6/64 + 7/128 + ... converges to 2. His diagram for his geometric proof, similar to the adjacent diagram, shows a two dimensional geometric series. The first dimension is horizontal, in the bottom row showing the geometric series S = 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/16 + ... , which is the geometric series with coefficient a = 1/2 and common ratio r = 1/2 that converges to S = a / (1-r) = (1/2) / (1-1/2) = 1. The second dimension is vertical, where the bottom row is a new coefficient aT equal to S and each subsequent row above it is scaled by the same common ratio r = 1/2, making another geometric series T = 1 + 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + ... , which is the geometric series with coefficient aT = S = 1 and common ratio r = 1/2 that converges to T = aT / (1-r) = S / (1-r) = a / (1-r) / (1-r) = (1/2) / (1-1/2) / (1-1/2) = 2.

Although difficult to visualize beyond three dimensions, Oresme's insight generalizes to any dimension d. Using the sum of the d−1 dimension of the geometric series as the coefficient a in the d dimension of the geometric series results in a d-dimensional geometric series converging to Sd / a = 1 / (1-r)d within the range |r|<1. Pascal's triangle and long division reveals the coefficients of these multi-dimensional geometric series, where the closed form is valid only within the range |r|<1.

Note that as an alternative to long division, it is also possible to calculate the coefficients of the d-dimensional geometric series by integrating the coefficients of dimension d−1. This mapping from division by 1-r in the power series sum domain to integration in the power series coefficient domain is a discrete form of the mapping performed by the Laplace transform. MIT Professor Arthur Mattuck shows how to derive the Laplace transform from the power series in this lecture video,[8] where the power series is a mapping between discrete coefficients and a sum and the Laplace transform is a mapping between continuous weights and an integral.

The closed forms of Sd/a are related to but not equal to the derivatives of S = f(r) = 1 / (1-r). As shown in the following table, the relationship is Sk+1 = f(k)(r) / k!, where f(k)(r) denotes the kth derivative of f(r) = 1 / (1-r) and the closed form is valid only within the range |r| < 1.

Applications[]

Repeating decimals[]

A repeating decimal can be thought of as a geometric series whose common ratio is a power of 1/10. For example:

The formula for the sum of a geometric series can be used to convert the decimal to a fraction,

The formula works not only for a single repeating figure, but also for a repeating group of figures. For example:

Note that every series of repeating consecutive decimals can be conveniently simplified with the following:

That is, a repeating decimal with repeat length n is equal to the quotient of the repeating part (as an integer) and 10n - 1.

Economics[]

In economics, geometric series are used to represent the present value of an annuity (a sum of money to be paid in regular intervals).

For example, suppose that a payment of $100 will be made to the owner of the annuity once per year (at the end of the year) in perpetuity. Receiving $100 a year from now is worth less than an immediate $100, because one cannot invest the money until one receives it. In particular, the present value of $100 one year in the future is $100 / (1 + ), where is the yearly interest rate.

Similarly, a payment of $100 two years in the future has a present value of $100 / (1 + )2 (squared because two years' worth of interest is lost by not receiving the money right now). Therefore, the present value of receiving $100 per year in perpetuity is

which is the infinite series:

This is a geometric series with common ratio 1 / (1 + ). The sum is the first term divided by (one minus the common ratio):

For example, if the yearly interest rate is 10% ( = 0.10), then the entire annuity has a present value of $100 / 0.10 = $1000.

This sort of calculation is used to compute the APR of a loan (such as a mortgage loan). It can also be used to estimate the present value of expected stock dividends, or the terminal value of a security.

Fractal geometry[]

In the study of fractals, geometric series often arise as the perimeter, area, or volume of a self-similar figure.

For example, the area inside the Koch snowflake can be described as the union of infinitely many equilateral triangles (see figure). Each side of the green triangle is exactly 1/3 the size of a side of the large blue triangle, and therefore has exactly 1/9 the area. Similarly, each yellow triangle has 1/9 the area of a green triangle, and so forth. Taking the blue triangle as a unit of area, the total area of the snowflake is

The first term of this series represents the area of the blue triangle, the second term the total area of the three green triangles, the third term the total area of the twelve yellow triangles, and so forth. Excluding the initial 1, this series is geometric with constant ratio r = 4/9. The first term of the geometric series is a = 3(1/9) = 1/3, so the sum is

Thus the Koch snowflake has 8/5 of the area of the base triangle.

Geometric power series[]

The formula for a geometric series

can be interpreted as a power series in the Taylor's theorem sense, converging where . From this, one can extrapolate to obtain other power series. For example,

See also[]

| Part of a series of articles about |

| Calculus |

|---|

- 0.999... – Alternative decimal expansion of the number 1

- Asymptote – Limit of the tangent line at a point that tends to infinity

- Divergent geometric series

- Generalized hypergeometric function

- Geometric progression

- Neumann series

- Ratio test

- Root test

- Series (mathematics) – Infinite sum

- Arithmetic series

Specific geometric series[]

- Grandi's series – The infinite sum of alternating 1 and -1 terms: 1 − 1 + 1 − 1 + ⋯

- 1 + 2 + 4 + 8 + ⋯ – Infinite series

- 1 − 2 + 4 − 8 + ⋯

- 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/16 + ⋯

- 1/2 − 1/4 + 1/8 − 1/16 + ⋯

- 1/4 + 1/16 + 1/64 + 1/256 + ⋯

- A geometric series is a unit series (the series sum converges to one) if and only if |r| < 1 and a + r = 1 (equivalent to the more familiar form S = a / (1 - r) = 1 when |r| < 1). Therefore, an alternating series is also a unit series when -1 < r < 0 and a + r = 1 (for example, coefficient a = 1.7 and common ratio r = -0.7).

- The terms of a geometric series are also the terms of a generalized Fibonacci sequence (Fn = Fn-1 + Fn-2 but without requiring F0 = 0 and F1 = 1) when a geometric series common ratio r satisfies the constraint 1 + r = r2, which according to the quadratic formula is when the common ratio r equals the golden ratio (i.e., common ratio r = (1 ± √5)/2).

- The only geometric series that is a unit series and also has terms of a generalized Fibonacci sequence has the golden ratio as its coefficient a and the conjugate golden ratio as its common ratio r (i.e., a = (1 + √5)/2 and r = (1 - √5)/2). It is a unit series because a + r = 1 and |r| < 1, it is a generalized Fibonacci sequence because 1 + r = r2, and it is an alternating series because r < 0.

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Riddle, Douglas F. Calculus and Analytic Geometry, Second Edition Belmont, California, Wadsworth Publishing, p. 566, 1970.

- ^ Abramowitz & Stegun (1972, p. 10)

- ^ Moise (1967, p. 48)

- ^ Protter & Morrey (1970, pp. 639–640)

- ^ Riddle, Douglas E (1974). Calculus and Analytic Geometry (2nd ed.). Wadsworth Publishing. p. 556. ISBN 053400301-X.

- ^ Euclid; J.L. Heiberg (2007). Euclid's Elements of Geometry (PDF). Translated by Richard Fitzpatrick. Richard Fitzpatrick. ISBN 978-0615179841.

- ^ Babb, J (2003). "Mathematical Concepts and Proofs from Nicole Oresme: Using the History of Calculus to Teach Mathematics" (PDF). Department of Mathematics & Statistics, University of Winnipeg, 515 Portage Avenue: The Seventh International History, Philosophy and Science Teaching conference. pp. 11–12, 21.CS1 maint: location (link)

- ^ Mattuck, Arthur. "Lecture 19, MIT 18.03 Differential Equations, Spring 2006". MIT OpenCourseWare.

References[]

- Abramowitz, M. and Stegun, I. A. (Eds.). Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables, 9th printing. New York: Dover, p. 10, 1972.

- Andrews, George E. (1998). "The geometric series in calculus". The American Mathematical Monthly. Mathematical Association of America. 105 (1): 36–40. doi:10.2307/2589524. JSTOR 2589524.

- Arfken, G. Mathematical Methods for Physicists, 3rd ed. Orlando, FL: Academic Press, pp. 278–279, 1985.

- Beyer, W. H. CRC Standard Mathematical Tables, 28th ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, p. 8, 1987.

- Courant, R. and Robbins, H. "The Geometric Progression." §1.2.3 in What Is Mathematics?: An Elementary Approach to Ideas and Methods, 2nd ed. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, pp. 13–14, 1996.

- James Stewart (2002). Calculus, 5th ed., Brooks Cole. ISBN 978-0-534-39339-7

- Larson, Hostetler, and Edwards (2005). Calculus with Analytic Geometry, 8th ed., Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 978-0-618-50298-1

- Moise, Edwin E. (1967), Calculus: Complete, Reading: Addison-Wesley

- Pappas, T. "Perimeter, Area & the Infinite Series." The Joy of Mathematics. San Carlos, CA: Wide World Publ./Tetra, pp. 134–135, 1989.

- Protter, Murray H.; Morrey, Charles B. Jr. (1970), College Calculus with Analytic Geometry (2nd ed.), Reading: Addison-Wesley, LCCN 76087042

- Roger B. Nelsen (1997). Proofs without Words: Exercises in Visual Thinking, The Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 978-0-88385-700-7

History and philosophy[]

- C. H. Edwards Jr. (1994). The Historical Development of the Calculus, 3rd ed., Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-94313-8.

- Swain, Gordon and Thomas Dence (April 1998). "Archimedes' Quadrature of the Parabola Revisited". Mathematics Magazine. 71 (2): 123–30. doi:10.2307/2691014. JSTOR 2691014.

- Eli Maor (1991). To Infinity and Beyond: A Cultural History of the Infinite, Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02511-7

- Morr Lazerowitz (2000). The Structure of Metaphysics (International Library of Philosophy), Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-22526-7

Economics[]

- Carl P. Simon and Lawrence Blume (1994). Mathematics for Economists, W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-95733-4

- Mike Rosser (2003). Basic Mathematics for Economists, 2nd ed., Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-26784-7

Biology[]

- Edward Batschelet (1992). Introduction to Mathematics for Life Scientists, 3rd ed., Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-09648-3

- Richard F. Burton (1998). Biology by Numbers: An Encouragement to Quantitative Thinking, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57698-7

Computer science[]

- John Rast Hubbard (2000). Schaum's Outline of Theory and Problems of Data Structures With Java, McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-137870-3

External links[]

- "Geometric progression", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Geometric Series". MathWorld.

- Geometric Series at PlanetMath.

- Peppard, Kim. "College Algebra Tutorial on Geometric Sequences and Series". West Texas A&M University.

- Casselman, Bill. "A Geometric Interpretation of the Geometric Series". Archived from the original (Applet) on 2007-09-29.

- "Geometric Series" by Michael Schreiber, Wolfram Demonstrations Project, 2007.

- Geometric series

- Ratios