Ginza Rabba

| Ginza Rabba ࡂࡉࡍࡆࡀ ࡓࡁࡀ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Information | |

| Religion | Mandaeism |

| Language | Mandaic language |

| Period | 1st century |

| Part of a series on |

| Mandaeism |

|---|

|

| Religion portal |

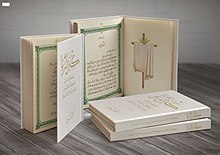

The Ginza Rabba (Classical Mandaic: ࡂࡉࡍࡆࡀ ࡓࡁࡀ, romanized: Ginzā Rbā, lit. 'Great Treasury'), Ginza Rba, or Sidra Rabba (Classical Mandaic: ࡎࡉࡃࡓࡀ ࡓࡁࡀ, romanized: Sidrā Rbā, lit. 'Great Book'), and formerly the Codex Nasaraeus,[1] is the longest and the most important holy scripture of Mandaeism. It is also occasionally referred to as the Book of Adam.[1]

Language, dating and authorship[]

The language used is Classical Mandaic, a variety of Eastern Aramaic written in the Mandaic script (Parthian chancellory script), similar to the Syriac script. The authorship is unknown, and dating is a matter of debate. Some scholars place it in the 2nd-3rd centuries,[2] while others such as S. F. Dunlap place it in the 1st century.[3]

The earliest confirmed Mandaean scribe was Shlama Beth Qidra, a woman, who copied the Left Ginza sometime around the year 200 CE.[4]

Structure[]

The Ginza Rabba is divided into two parts – the Right Ginza, containing 18 books, and the Left Ginza, containing 3 books. In Mandaic studies, the Right Ginza is commonly abbreviated as GR, while the Left Ginza is commonly abbreviated as GL.[5]

Ginza Rabba codices traditionally contain the Right Ginza on one side, and, when turned upside-down and back to front, contain the Left Ginza (the Left Ginza is also called "The Book of the Dead"). The Right Ginza part of the Ginza Rabba contains sections dealing with theology, creation, ethics, historical, and mythical narratives; its six colophons reveal that it was last redacted in the early Islamic Era. The Left Ginza section of Ginza Rabba deals with man's soul in the afterlife; its colophon reveals that it was redacted for the last time hundreds of years before the Islamic Era.[5][6]

There are various manuscript versions that differ from each other. The versions order chapters differently from each other, and textual content also differs.

The Ginza Rabba is divided into two parts – the Right Ginza, containing 18 books, and the Left Ginza, containing 3 books. In Mandaic studies, the Right Ginza is commonly abbreviated as GR, while the Left Ginza is commonly abbreviated as GL.[5]

Contents[]

The Ginza Rabba is a compilation of various oral teachings and written texts, most predating their editing into the two volumes. It includes literature on a wide variety of topics, including liturgy and hymns, theological texts, didactic texts, as well as both religious and secular poetry.[5]

For a comprehensive listing of summaries of each chapter in the Ginza Rabba, see the articles Right Ginza and Left Ginza.

Manuscript versions[]

Manuscript versions of the Ginza include the following. Two are held in the Bodleian Library at Oxford, three in the British Library in London, four in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, and others are in private ownership.[7]

- Bodleian Library manuscripts

- DC 22

- Huntington Ms. 6

- British Library manuscripts catalogued under the same title, Liber Adami Mendaice

- Add. 23,599

- Add. 23,600

- Add. 23,601

- Paris manuscripts, Bibliothèque nationale de France (consulted by Lidzbarski for his 1925 German translation)

- Paris Ms. A

- Paris Ms. B (also called the "Norberg version," since it was used by Norberg during the early 1800s)

- Paris Ms. C

- Paris Ms. D

For his 1925 German translation of the Ginza, Lidzbarski also consulted other Ginza manuscripts that were held at Leiden and Munich.[8]

Buckley has also found Ginza manuscripts that are privately held by Mandaeans in the United States (two in San Diego, California belonging to Lamea Abbas Amara; one in Flushing, New York belonging to Nasser Sobbi; and one in Lake Grove, New York belonging to Mamoon Aldulaimi, originally given to him by Sheikh Abdullah, son of Sheikh Negm).[7] A version of the Ginza by Mhatam Yuhana was also used by Gelbert in his 2011 English translation of the Ginza. Another manuscript known to Gelbert is a privately owned Ginza manuscript in Ahvaz belonging to Shaikh Abdullah Khaffaji,[8] the grandson of Ram Zihrun.[9]

Printed versions of the Ginza in Mandaic include:

- Norberg version (Mandaic): A printed Ginza in Mandaic was published by Matthias Norberg in 1816.

- Petermann version (Mandaic): A printed Ginza in Mandaic was published by Julius Heinrich Petermann in 1867.

- Mubaraki version (Mandaic): The full Ginza Rabba in the Mandaic script was first printed by the Mandaean community in Sydney, Australia in 1998.[10] At present, there are two published Mandaic-language editions of the Ginza published by Mandaeans themselves.

- Gelbert version (Mandaic, in Arabic script): The full Mhatam Yuhana Ginza manuscript from Ahvaz, Iran was transcribed in Arabic script by Carlos Gelbert in 2021. As the fourth edition of the Gelbert's Arabic Ginza, Gelbert (2021) contains an Arabic translation side by side with the Mandaic transcription.[11]

Translations[]

Notable translations and printed versions of the Ginza Rabba include:

- Norberg version (Latin): From 1815 to 1816, Matthias Norberg published a Latin translation of the Ginza Rabba, titled Codex Nasaraeus liber Adami appellatus (3 volumes). The original Mandaic text was also printed alongside the Latin translation.[1]

- Petermann version (Latin): In 1867, Julius Heinrich Petermann published a Latin translation of the Ginza Rabba, which was based on four different Ginza manuscripts held at Paris.[12]

- Lidzbarski version (German): In 1925, Mark Lidzbarski published the German translation Der Ginza oder das grosse Buch der Mandäer.[13] Lidzbarski translated an edition of the Ginza by Julius Heinrich Petermann from the 1860s, which in turn relied upon four different Ginza manuscripts held at Paris. Lidzbarski was also able to include some material from a fifth Ginza which was held at Leiden.

- Baghdad version (Arabic, abridged): An Arabic translation of the Ginza Rabba was first published in Baghdad in 2001.[14]

- Gelbert version (English translation in 2011; Arabic translation in 2021): The first full English translation of the Ginza Rba was published by Carlos Gelbert in 2011, with the collaboration of Mark J. Lofts and other editors.[8] It is mostly based on the Mhatam Yuhana Ginza Rba from Iran (transcribed in the late 1990s under the supervision of Mhatam Yuhana, the ganzibra or head-priest of the Mandaean Council of Ahvaz in Iran) and also on Mark Lidzbarski's 1925 German translation of the Ginza.[15] Gelbert's 2011 edition is currently the only full-length English translation of the Ginza that contains detailed commentary, with extensive footnotes and many original Mandaic phrases transcribed in the text. An Arabic translation (fourth edition) of the Ginza was also published by Gelbert in 2021, with the book also containing the original Mandaic text transcribed in Arabic script.[11]

- Al-Saadi (Drabsha) version (English, abridged): Under the official auspices of the Mandaean spiritual leadership, Drs. Qais Al-Saadi and Hamed Al-Saadi published an English translation of the Ginza Rabba: The Great Treasure in 2012. In 2019, the second edition was published by Drabsha in Germany. The translation, endorsed by the Mandaean Patriarch Sattar Jabbar Hilo, is designed for contemporary use by the Mandaean community and is based on an Arabic translation of the Ginza Rabba that was published in Baghdad.[16][17][18] However, it has been criticized for being overly abridged and paraphrased.[19]

See also[]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Ginza Rabba |

References[]

- ^ a b c Norberg, Matthias. Codex Nasaraeus Liber Adami appellatus. 3 vols. London, 1815–16.

- ^ The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran: Their Cults, Customs, Magic Page 20 E. S. Drower, Jorunn Jacobsen Buckley - 2002 "Their authorship and the date at which each fragment, possibly originally memorized, was committed to writing is even more problematic. Even such a book as the Ginza Rabba cannot be regarded as homogeneous, for it is a collection of ...."

- ^ "Sod, The Son of the Man" Page iii, S. F. Dunlap, Williams and Norgate - 1861

- ^ Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen. The Mandaeans: Ancient Texts and Modern People. Oxford University Press, 2002. Page 4.

- ^ a b c d Häberl, Charles G. (2007). Introduction to the New Edition, in The Great Treasure of the Mandaeans, a new edition of J. Heinrich Petermann's Thesaurus s. Liber Magni, with a new introduction and a translation of the original preface by Charles G. Häberl. Gorgias Press, LLC. doi:10.7282/T3C53J6P

- ^ Aldihisi, Sabah (2008). The story of creation in the Mandaean holy book in the Ginza Rba (PhD). University College London.

- ^ a b Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen (2010). The great stem of souls: reconstructing Mandaean history. Piscataway, N.J: Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-59333-621-9.

- ^ a b c Gelbert, Carlos (2011). Ginza Rba. Sydney: Living Water Books. ISBN 9780958034630.

- ^ Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen (2002). The Mandaeans: ancient texts and modern people. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515385-5. OCLC 65198443.

- ^ Majid Fandi al-Mubaraki, Haitham Mahdi Saaed, and Brian Mubaraki (eds.), Ginza Rabba: The Great Treasure (Sydney: Majid Fandi al-Mubaraki, 1998).

- ^ a b Gelbert, Carlos (2021). گینزا ربَّا = Ginza Rba (in Arabic). Edensor Park, NSW, Australia: Living Water Books. ISBN 9780648795407.

- ^ Petermann, Heinrich. 1867. Sidra Rabba: Thesaurus sive Liber Magnus vulgo "Liber Adami" appellatus, opus Mandaeorum summi ponderis. Vols. 1–2. Leipzig: Weigel.

- ^ Lidzbarski, Mark (1925). Ginza: Der Schatz oder Das große Buch der Mandäer. Göttingen: Vandenhoek & Ruprecht.

- ^ Yūsuf Mattī Qūzī; Ṣabīḥ Madlūl Suhayrī; ʻAbd al-Razzāq ʻAbd al-Wāḥid; Bashīr ʻAbd al-Wāḥid Yūsuf (2001). گنزا ربا = الكنز العظيم : الكتاب المقدس للصابئة المندائيين / Ginzā rabbā = al-Kanz al-ʻaẓīm: al-Kitāb al-muqaddas lil-Ṣābiʼah al-Mandāʼīyīn. Baghdad: اللجنة العليا المشرفة على ترجمة گنزا ربا / al-Lajnah al-ʻUlyā al-mushrifah ʻalá tarjamat Ginzā Rabbā. OCLC 122788344. (Pages 1-136 (2nd group: al-Yasār) are bound upside down according to Mandaean tradition.)

- ^ "About the author". Living Water Books. Retrieved 2021-09-05.

He has translated Lidzbarski's books from the German to two different languages: English and Arabic.

- ^ Al-Saadi, Qais Mughashghash; Al-Saadi, Hamed Mughashghash (2012). Ginza Rabba: The Great Treasure. An equivalent translation of the Mandaean Holy Book. Drabsha.

- ^ "Online Resources for the Mandaeans". Hieroi Logoi. 2013-05-30. Retrieved 2017-12-27.

- ^ Al-Saadi, Qais (2014-09-27). "Ginza Rabba "The Great Treasure" The Holy Book of the Mandaeans in English". Mandaean Associations Union. Retrieved 2021-09-21.

- ^ Gelbert, Carlos (2017). The Teachings of the Mandaean John the Baptist. Fairfield, NSW, Australia: Living Water Books. ISBN 9780958034678. OCLC 1000148487.

External links[]

- German translation (1925) by Mark Lidzbarski at the Internet Archive (Commons file)

- Volumes 1 and 2 and Volume 3 of Codex Nasaraeus: liber Adami appellatus, syriace transscriptus ... latineque redditus (an 1815 edition in Syriac transcription, with Latin translation, by Matthias Norberg)

- Book seven of the Ginza Rabba (Words of John the Baptist) – English Translation on Wikisource

- Ginza Rabba (Mandaic text from the Mandaean Network)

- Ginza Rabba (Mandaic text from the Mandaean Network)

- Ginza Rabba concordance (Mandaic text from the Mandaean Network)

- 1st-century texts

- 2nd-century texts

- 3rd-century texts

- Mandaean texts