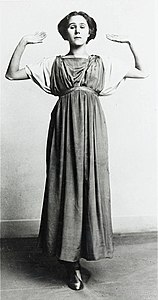

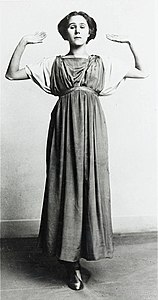

Grete Wiesenthal

Grete Wiesenthal | |

|---|---|

From the time of my first dance, from her autobiography, Der Aufstieg (1919) | |

| Born | December 9, 1885 Vienna |

| Died | June 22, 1970 (aged 84) Vienna |

| Nationality | Austrian |

| Alma mater | Vienna State Opera |

| Known for | Ecstatic modern dance[1] |

Notable work | Choreography for The Blue Danube |

| Relatives | Elsa (sister, danced with her) |

Grete Wiesenthal (9 December 1885 - 22 June 1970) was an Austrian dancer, actor, choreographer, and dance teacher. She transformed the Viennese Waltz from a staple of the ballroom into a wildly ecstatic dance.

Early life[]

Grete Wiesenthal was born in Vienna in 1885, daughter of the painter Franz Wiesenthal and his wife Rosa nee Ratkovsky. She had five sisters and a brother.[2] At the age of ten she joined the ballet school of the Court Opera in Vienna, as did her sister Elsa, and from 1901 to 1907 she worked as a dancer there. In 1907, Gustav Mahler gave her the leading role of 'Fenella' in Die Stumme von Portici.[3]

Career[]

Wiesenthal felt there was no artistry in the Court Opera, and developed her own approach to the Viennese Waltz of Strauss and the waltzes of Chopin,[4][5][6] linked to the Vienna Secession group of artists and innovators.[2] Her dramatic and ecstatic[1] choreography of the dance with "swirling, euphoric movement and suspended arches of the body",[4] the dancers "with unbound hair and swinging dresses",[2] made her a leading figure in Austrian dance.[4][2][7] She called her approach "spherical dance", involving turning and extending the torso, arms, and legs on a horizontal axis, unlike the more vertical rotations of her contemporaries Isadora Duncan and Ruth St Denis, who were also admired at that time in Vienna. Spinning was a core element in her dance.[4] The cultural historian Alys X. George said that this transformation of the Viennese waltz from ballroom standard to an outdoor avant-garde art form electrified the city.[4]

In 1908, Wiesenthal led her sisters Berta and Elsa at Vienna's Cabaret Fledermaus, the highlight being her "Donauwalzer" solo performed to Johann Strauss II's "On the Beautiful Blue Danube".[4] They moved to Berlin, working there until 1910 at the Deutsches Theater.[2][5] They toured both in Germany and internationally, taking their dance to Munich (Artist's Theatre, 1909)[2] London (Hippodrome 1909),[4] Paris (Théâtre du Vaudeville),[2] and New York (1912, Winter Theater) where they were warmly received.[4] Critics repeatedly commented on her delicacy of movement, charm, and femininity. However the leading ballerina , who danced Wiesenthal's works in the late 20th century, noted that the tiny movements were less well-suited to the large stage of the Vienna State Opera.[4]

In 1912-1914, she led in the three "Grete Wiesenthal Series" films, Kadra Sâfa, Erlkönigs Tochter, and Die goldne Fliege.[2]

After a pause in her career for the First World War, she opened her own school of dance in 1919.[2] In 1927, she took the leading role in her own ballet Der Taugenichts in Wien ("The Ne'er-Do-Well in Vienna") at the Vienna State Opera. She continued to give dance performances in Vienna and on tour. Her performances on her return to New York in 1933 however appeared dated to critics.[2][4] In 1934, she became a professor at the Academy for Music and the Performing Arts in Vienna, and in 1945 she became director of artistic dance there.[2]

Wiesenthal dancing to Beethoven's Piano concerto in G major, by Moritz Nähr, 1906/8

Wiesenthal's interpretation of Strauss's Danube waltzes, 1908, by Arnold Genthe

Wiesenthal dancing Johann Strauss II's Frühlingsstimmen, by , 1910

The dancer, by Hugo Erfurth, 1928

Family life and legacy[]

Wiesenthal married Erwin Lang in June 1910, divorcing in 1923. She married the Swedish doctor Nils Silfverskjöld that same year, divorcing in 1927. She had one son, Martin.[2]

She is buried in the Central Cemetery in Vienna. She is "revered" in Austria as a pioneer of modern dance, where her choreography saw a late 20th century renaissance.[4][2] In 2020, Gunhild Oberzaucher-Schüller described her dance on Tanz.at as "ever present".[8] In 1981 a street in Vienna's Favoriten district was named Wiesenthalgasse after her.

Works[]

Ballet[]

- 1908: Der Geburtstag der Infantin (Music by Franz Schreker)

- 1916: Die Biene (Music by Clemens von Franckenstein)

- 1930: Der Taugenichts von Wien (Music by Franz Salmhofer)

Books[]

- 1919: Der Aufstieg ("The Climb", Autobiography)

- 1951: Iffi: Roman einer Tänzerin ("Iffi: A Dancer's Novel")[2]

Filmography[]

- 1913: Das fremde Mädchen (Den okända)

- 1914: Die goldene Fliege

- 1914: Erlkönigs Tochter

- 1914: Kadra Sâfa

- 1919: Der Traum des Künstlers

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Amort, Andrea (21 June 2020). "'Die Schäbigen sind unerschüttert': Briefwechsel von Grete Wiesenthal mit Lily Calderon-Spitz" ['The shabby are unshaken': Correspondence between Grete Wiesenthal and Lily Calderon-Spitz] (in German). Vienna Museum Magazine. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Grete Wiesenthal (1885-1970)". Mahler Foundation. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ de La Grange, Henry-Louis (2007). Gustav Mahler. 3. Vienna: Triumph and Disillusion (1904-1907). Oxford University Press. pp. 620–625. ISBN 978-0193151604. OCLC 916615081.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k Cates, Meryl (24 December 2020). "Dancing by Herself: When the Waltz Went Solo". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Grete Wiesenthal". Oxford Reference. 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ Franke, Verena (4 April 2019). "Frauen in Bewegung: "Alles tanzt" im Theatermuseum arbeitet die Wiener Tanzmoderne auf". Wiener Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ Oberzaucher-Schüller, Gunhild (6 June 2001). "Wiesenthal, Schwestern" [Wiesenthal Sisters] (in German). Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon online. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ Oberzaucher-Schüller, Gunhild (24 June 2020). "„Frei und ungebunden in leidenschaftlichen Rhythmen"" (in German). tanz.at. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

Sources[]

- Rudolf Huber-Wiesenthal: Die Schwestern Wiesenthal. 1934.

- Ingeborg Prenner: Grete Wiesenthal. Die Begründerin eines neuen Tanzstils. PhD thesis, Vienna, 1950.

- Die neue Körpersprache – Grete Wiesenthal und ihr Tanz. (Exhibition Catalogue: Vienna Museum, 18 May 1985 - 23 February 1986). 1985.

- Leonard M. Fiedler and Martin Lang: Grete Wiesenthal. Die Schönheit der Sprache des Körpers im Tanz. Residenz Verlag, Salzburg und Wien 1985.

- Andrea Amort: "Free Dance in Interwar Vienna" In: Interwar Vienna. Culture between Tradition and Modernity. Eds. Deborah Holmes and Lisa Silverman. New York, Camden House, 2009, pp. 117–142.

- and : Mundart der Wiener Moderne. Der Tanz der Grete Wiesenthal. Kieser, München 2009.

- Alexandra Kolb: Performing Femininity. Dance and Literature in German Modernism. Oxford: Peter Lang 2009.

External links[]

- Austrian ballerinas

- 1885 births

- 1970 deaths

- Dancers from Vienna

- Austrian female dancers

- 20th-century ballet dancers