History of the United Kingdom during the First World War

| 1914–1918 | |

British First World War propaganda poster | |

| Preceded by | Edwardian era |

|---|---|

| Followed by | Interwar Britain |

| Monarch(s) | George V |

| Leader(s) | Civil

Army

Royal Navy

RNAS & RFC

|

|

Timeline of the United Kingdom during the First World War |

| History of the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

|

|

| Periods in English history |

|---|

| Timeline |

The United Kingdom was a leading Allied Power during the First World War of 1914–1918, fighting against the Central Powers, especially Germany. The armed forces were greatly expanded and reorganised—the war marked the founding of the Royal Air Force. The highly controversial introduction, in January 1916, of conscription for the first time in British history followed the raising of the largest all-volunteer army in history, known as Kitchener's Army, of more than 2,000,000 men.[1]: 504 The outbreak of war was a socially unifying event.[2] Enthusiasm was widespread in 1914, and was similar to that across Europe.[3]

On the eve of war, there was serious domestic unrest amongst the labour and suffrage movements and especially in Ireland. But those conflicts were postponed. Significant sacrifices were called for in the name of defeating the Empire's enemies and many of those who could not fight contributed to philanthropic and humanitarian causes. Fearing food shortages and labour shortfalls, the government passed legislation such as the Defence of the Realm Act 1914, to give it new powers. The war saw a move away from the idea of "business as usual" under Prime Minister H. H. Asquith,[4] and towards a state of total war (complete state intervention in public affairs) by 1917 under the premiership of David Lloyd George;[5] the first time this had been seen in Britain. The war also witnessed the first aerial bombardments of cities in Britain.

Newspapers played an important role in maintaining popular support for the war.[6] Large quantities of propaganda were produced by the government under the guidance of such journalists as Charles Masterman and newspaper owners such as Lord Beaverbrook. By adapting to the changing demographics of the workforce (or the "dilution of labour", as it was termed), war-related industries grew rapidly, and production increased, as concessions were quickly made to trade unions.[7] In that regard, the war is also credited by some with drawing women into mainstream employment for the first time.[8] Debates continue about the impact the war had on women's emancipation, given that a large number of women were granted the vote for the first time in 1918. The experience of individual women during the war varied; much depended on locality, age, marital status and occupation.[9][10]

The civilian death rate rose due to food shortages and Spanish flu, which hit the country in 1918.[11] Military deaths are estimated to have exceeded 850,000.[12] The Empire reached its zenith at the conclusion of peace negotiations.[13] However, the war heightened not only imperial loyalties but also individual national identities in the Dominions (Canada, Newfoundland, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa) and India. Irish nationalists after 1916 moved from collaboration with London to demands for immediate independence (see Easter Rising), a move given great impetus by the Conscription Crisis of 1918.[14]

Military historians continue to debate matters of tactics and strategy. However, in terms of memory of the war, historian Adrian Gregory argues that:

- "The verdict of popular culture is more or less unanimous. The First World War was stupid, tragic and futile. The stupidity of the war has been a theme of growing strength since the 1920s. From Robert Graves, through 'Oh! What a Lovely War' to 'Blackadder Goes Forth,' the criminal idiocy of the British High Command has become an article of faith."[15]

Government[]

Asquith as prime minister[]

On 4 August, King George V declared war on the advice of his prime minister, H. H. Asquith, leader of the Liberal Party. Britain's basic reasons for declaring war focused on a deep commitment to France and avoidance of splitting the Liberal Party. Top Liberals threatened to resign if the cabinet refused to support France—which would mean loss of control of the government to a coalition or to the Unionist (i.e. Conservative) opposition. However, the large antiwar element among Liberals would support the war to honour the 1839 treaty regarding guarantees of Belgian neutrality, so that rather than France was the public reason given.[16][17] Therefore, the public reason given out by the government. and used in posters, was that Britain was required to safeguard Belgium's neutrality under the 1839 Treaty of London.

The strategic risk posed by German control of the Belgian and ultimately French coast was considered unacceptable. German guarantees of post-war behaviour were cast into doubt by her blasé treatment of Belgian neutrality. However, the Treaty of London had not committed Britain on her own to safeguard Belgium's neutrality. Moreover, naval war planning demonstrated that Britain herself would have violated Belgian neutrality by blockading her ports (to prevent imported goods passing to Germany) in the event of war with Germany.

Britain's duty to her Entente partners, both France and Russia, were paramount factors. The Foreign Secretary Edward Grey argued that the secret naval agreements with France created a moral obligation 'to save France from defeat by Germany. British national interest rejected German control of France, Belgium and the Netherlands. Grey warned that to abandon its allies would be a permanent disaster: if Germany won the war, or the Entente won without British support, then, either way, Britain would be left without any friends. This would have left both Britain and her Empire vulnerable to isolation.[18]

Eyre Crowe, a senior Foreign office expert said:

Should the war come, and England stand aside, one of two things must happen. (a) Either Germany and Austria win, crush France and humiliate Russia. What will be the position of a friendless England? (b) Or France and Russia win. What would be their attitude towards England? What about India and the Mediterranean?[19]: 544

Crisis of Liberal leadership[]

The Liberal Party might have survived a short war, but the totality of the Great War called for strong measures that the Party had long rejected. The result was the permanent destruction of the ability of the Liberal Party to lead a government. Historian Robert Blake explains the dilemma:

- the Liberals were traditionally the party of freedom of speech, conscience and trade. They were against jingoism, heavy armaments and compulsion....Liberals were neither wholehearted nor unanimous about conscription, censorship, the Defence of the Realm Act, severity toward aliens and pacifists, direction of labour and industry. The Conservatives... had no such misgivings.[20]

Blake further notes that it was the Liberals, not the Conservatives who needed the moral outrage of Belgium to justify going to war, while the Conservatives called for intervention from the start of the crisis on the grounds of realpolitik and the balance of power.[21]

The British people were disappointed that there was no quick victory in the war. They long had taken great pride and expense in the Royal Navy, but now there was little to cheer about. The Battle of Jutland in May 1916, was the first and only time the German fleet challenged control of the North Sea, but it was overmatched and was reassigned mostly to helping the more important U-boats. Since the Liberals ran the war without consulting the Unionists (Conservatives) there were heavy partisan attacks. However even Liberal commentators were dismayed by the lack of energy at the top. At the time public opinion was intensely hostile, both in the media and in the street, against any young man in civilian garb and labeled as a slacker. The leading Liberal newspaper, the Manchester Guardian complained:

- The fact that the Government has not dared to challenge the nation to rise above itself, is one among many signs... The war is, in fact, not being taken seriously.... How can any slacker be blamed when the Government itself is slack.[22]

Asquith's Liberal government was brought down in May 1915, due in particular to a crisis in inadequate artillery shell production and the protest resignation of Admiral Fisher over the disastrous Gallipoli Campaign against Turkey. Reluctant to face doom in an election, Asquith formed a new coalition government on 25 May, with the majority of the new cabinet coming from his own Liberal party and the Unionist (Conservative) party, along with a token Labour representation. The new government lasted a year and a half, and was the last time Liberals controlled the government.[23] The analysis of historian A. J. P. Taylor is that the British people were so deeply divided over numerous issues, But on all sides there was growing distrust for the Asquith government. There was no agreement whatsoever on wartime issues. The leaders of the two parties realized that embittered debates in Parliament would further undermine popular morale, and so the House of Commons did not once discuss the war before May 1915. Taylor argues:[24]

- The Unionists, by and large, regarded Germany as a dangerous rival, and rejoiced at the chance to destroy her. They meant to fight a hard-headed war by ruthless methods; the condemned Liberal 'softness' before the war and now. The Liberals insisted on remaining high-minded. Many of them income to support the war only when the Germans invaded Belgium....Entering the war for idealistic motives, the Liberals wish to fight it by noble means and found it harder to abandon their principles than to endure your defeat in the field.

Lloyd George as prime minister[]

This coalition government lasted until 1916, when the Unionists became dissatisfied with Asquith and the Liberals' conduct of affairs, particularly over the Battle of the Somme.[25] Asquith's opponents now took control, led by Bonar Law (leader of the Conservatives), Sir Edward Carson (leader of the Ulster Unionists), and David Lloyd George (then a minister in the cabinet). Law, who had few allies outside his own party, lacked sufficient support to form a new coalition; the Liberal Lloyd George, on the other hand, enjoyed much wider support and duly formed a majority-Conservative coalition government with Lloyd George Liberals and Labour. Asquith was still the party head but he and his followers moved to the opposition benches in Parliament.[26]

Lloyd George immediately set about transforming the British war effort, taking firm control of both military and domestic policy.[27][28] In the first 235 days of its existence, the War Cabinet met 200 times.[5] Its creation marked the transition to a state of total war—the idea that every man, woman and child should play his or her part in the war effort. Moreover, it was decided that members of the government should be the men who controlled the war effort, primarily utilising the power they had been given under the Defence of the Realm Act.[5] For the first time, the government could react quickly, without endless bureaucracy to tie it down, and with up-to-date statistics on such matters as the state of the merchant navy and farm production.[5] The policy marked a distinct shift away from Asquith's initial policy of laissez-faire,[4] which had been characterised by Winston Churchill's declaration of "business as usual" in November 1914.[29] The success of Lloyd George's government can also be attributed to a general lack of desire for an election, and the practical absence of dissent that this brought about.[30]

In rapid succession in spring 1918 came a series of military and political crises.[31] The Germans, having moved troops from the Eastern front and retrained them in new tactics, now had more soldiers on the Western Front than the Allies. On 21 March 1918 Germany launched a full scale Spring Offensive against the British and French lines, hoping for victory on the battlefield before United States troops arrived in large numbers. The Allied armies fell back 40 miles in confusion, and facing defeat London realized it needed more troops to fight a mobile war. Lloyd George found half a million soldiers and rushed them to France, asked American President Woodrow Wilson for immediate help, and agreed to the appointment of the French Marshal Foch as commander in chief on the Western Front, so that Allied forces could be coordinated to handle the German offensive.[32]

Despite strong warnings that it was a bad idea, the War Cabinet decided to impose conscription on Ireland in 1918. The main reason was that labour in Britain demanded it as the price for cutting back on exemptions for certain workers. Labour wanted the principle established that no one was exempt, but it did not demand that conscription should actually take place in Ireland. The proposal was enacted, but never enforced. The Roman Catholic bishops for the first time entered the fray, calling for open resistance to compulsory military service, while the majority of Irish nationalists moved to supporting the intransigent Sinn Féin movement (away from the constitutional Irish National Party). This proved a decisive moment, marking the end of Irish willingness to stay inside the Union.[33][34]

On 7 May 1918, a senior army officer on active duty, Major-General Sir Frederick Maurice, prompted a second crisis when he went public with allegations that Lloyd George had lied to Parliament on military matters. Asquith, the Liberal leader in the House, took up the allegations and attacked Lloyd George (also a Liberal). While Asquith's presentation was poor, Lloyd George vigorously defended his position, treating the debate as a vote of confidence. He won over the House with a powerful refutation of Maurice's allegations. The main results were to strengthen Lloyd George, weaken Asquith, end public criticism of overall strategy, and strengthen civilian control of the military.[35][36] Meanwhile, the German offensive stalled and was ultimately reversed. Victory came on 11 November 1918.[37]

Historian George H. Cassar has evaluated Lloyd George's legacy as a war leader:

- After all that has been said and done, what are we to make of Lloyd George’s legacy as a war leader? On the home front he achieved varied results in tackling difficult, and in some instances, unprecedented problems. It would be hard to have improved on his dealings with labour and the program to increase homegrown food, but in the sectors of manpower, price control and food distribution he adopted the same approach as his predecessor, taking action only in response to the changing nature of the conflict. In the vital area of national morale, while he did not have the technical advantages of Churchill, his personal conduct damaged his ability to do more to inspire the nation. All things considered, it is unlikely that any of his political contemporaries could have handled matters at home as effectively as he did, although it can be argued that if someone else had been in charge, the difference would not have been sufficient to change the final outcome. In his conduct of the war he did advance the cause of the Entente significantly in some ways, but in determining strategy, one of the most important tasks for which a prime minister must be responsible, he was undeniably a failure. To sum up, while Lloyd George's contributions outweighed his mistakes, the margin is too narrow, in my opinion, to include him In the pantheon of Britain's outstanding war leaders.[38]

Collapse of the Liberal Party[]

In the general election of 1918, Lloyd George, "the Man Who Won the War", led his coalition into another khaki election and won a sweeping victory over the Asquithian Liberals and the newly emerging Labour Party. Lloyd George and the Conservative leader Bonar Law wrote a joint letter of support to candidates to indicate they were considered the official Coalition candidates – this "coupon", as it became known, was issued to opponents of many sitting Liberal MPs, devastating the incumbents.[39] Asquith and most of his Liberal colleagues lost their seats. Lloyd George was increasingly under the influence of the rejuvenated Conservative party. The Liberal party never recovered.[40]

Finance[]

Before the war, the government spent 13 percent of gross national product (GNP); in 1918 it spent 59 percent of GNP. The war was financed by borrowing large sums at home and abroad, by new taxes, and by inflation. It was implicitly financed by postponing maintenance and repair, as well as cancelling projects deemed unnecessary.[41] The government avoided indirect taxes because they raised the cost of living, and caused discontent among the working class. In 1913–14, indirect taxes on tobacco and alcohol yielded £75 million, while direct taxes yielded £88 million, including an income tax of £44 million and estate duties of £22 million. That is, 54 percent of revenue came from direct taxes; by 1918, direct taxes were 80 percent of revenue.[42] There was a strong emphasis on being "fair" and being "scientific." The public generally supported the heavy new taxes, with minimal complaints. The Treasury rejected proposals for a stiff capital levy, which the Labour Party wanted to use to weaken the capitalists. Instead, there was an excess profits tax, of 50 percent of profits above the normal prewar level; the rate was raised to 80 percent in 1917.[43][44] Excise taxes were added on luxury imports such as automobiles, clocks and watches. There was no sales tax or value added tax. The main increase in revenue came from income tax, which in 1915 went up to 3s. 6d in the pound (17.5%), and individual exemptions were lowered. The income tax rate grew to 5s in the pound (25%) in 1916, and 6s (30%) in 1918. Altogether, taxes provided at most 30 percent of national expenditure, with the rest from borrowing. The national debt soared from £625 million to £7,800 million. Government bonds typically paid five percent. Inflation escalated so that the pound in 1919 purchased only a third of the basket it had purchased it 1914. Wages were laggard, and the poor and retired were especially hard hit.[45][46]

Monarchy[]

A 1917 Punch cartoon depicts King George sweeping away his German titles.

The British royal family faced a serious problem during the First World War because of its blood ties to the ruling family of Germany, Britain's prime adversary in the war. Before the war, the British royal family had been known as the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. In 1910, George V became king on the death of his father, Edward VII, and reigned throughout the war. He was the first cousin of the German Emperor Wilhelm II, who came to symbolise all the horrors of the war. Queen Mary, although British like her mother, was the daughter of the Duke of Teck, a descendant of the royal House of Württemberg. During the war H. G. Wells wrote about Britain's "alien and uninspiring court", and George famously replied: "I may be uninspiring, but I'll be damned if I'm alien."[47]

On 17 July 1917, to appease British nationalist feelings, King George issued an Order in Council that changed the name of his family to the House of Windsor. He specifically adopted Windsor as the surname for all descendants of Queen Victoria then living in Britain, excluding women who married into other families and their descendants.[48] He and his relatives who were British subjects relinquished the use of all German titles and styles, and adopted English surnames. George compensated several of his male relatives by creating them British peers. Thus, his cousin, Prince Louis of Battenberg, became the Marquess of Milford Haven, while his brother-in-law, the Duke of Teck, became the Marquess of Cambridge. Others, such as Princess Marie Louise of Schleswig-Holstein and Princess Helena Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein, simply stopped using their territorial designations. The system for titling members of the royal family was also simplified.[49] Relatives of the British royal family who fought on the German side were simply cut off; their British peerages were suspended by a 1919 Order in Council under the provisions of the Titles Deprivation Act 1917.[50]

Developments in Russia posed another set of issues for the monarchy. Tsar Nicholas II of Russia was King George's first cousin and the two monarchs looked very much alike.[51] When Nicholas was overthrown in the Russian Revolution of 1917, the liberal Russian Government asked that the tsar and his family be given asylum in Britain. The cabinet agreed but the king was worried that public opinion was hostile and said no. It is likely the tsar would have refused to leave Russia in any case. He remained and in 1918 he and his family were ordered killed by Lenin, the Bolshevik leader.[52][53]

The Prince of Wales – the future Edward VIII – was keen to participate in the war but the government refused to allow it, citing the immense harm that would occur if the heir to the throne were captured.[54] Despite this, Edward witnessed trench warfare at first hand and attempted to visit the front line as often as he could, for which he was awarded the Military Cross in 1916. His role in the war, although limited, led to his great popularity among veterans of the conflict.[55][56]

Other members of the royal family were similarly involved. The Duke of York (later George VI) was commissioned in the Royal Navy and saw action as a turret officer aboard HMS Collingwood at the battle of Jutland but saw no further action in the war, largely because of ill health.[57] Princess Mary, the King's only daughter, visited hospitals and welfare organisations with her mother, assisting with projects to give comfort to British servicemen and assistance to their families. One of these projects was Princess Mary's Christmas Gift Fund, through which £162,000 worth of gifts was sent to all British soldiers and sailors for Christmas 1914.[58] She took an active role in promoting the Girl Guide movement, the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD), the Land Girls and in 1918, she took a nursing course and went to work at Great Ormond Street Hospital.[59]

Defence of the Realm Act[]

The first Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) was passed on 8 August 1914, during the early weeks of the war,[60] though in the next few months its provisions were extended.[61] It gave the government wide-ranging powers,[61] such as the ability to requisition buildings or land needed for the war effort.[62] Some of the things the British public were prohibited from doing included loitering under railway bridges,[63] feeding wild animals[64] and discussing naval and military matters.[65] British Summer Time was also introduced.[66] Alcoholic beverages were now to be watered down, pub closing times were brought forward from 12.30 am to 10 pm, and, from August 1916, Londoners were no longer able to whistle for a cab between 10 pm and 7 am.[66] It has been criticised for both its strength and its use of the death penalty as a deterrent[67] – although the act itself did not refer to the death penalty, it made provision for civilians breaking these rules to be tried in army courts martial, where the maximum penalty was death.[68]

Internment[]

The Aliens Restriction Act, passed on 5 August, required all foreign nationals to register with the police, and by 9 September just under 67,000 German, Austrian and Hungarian nationals had done so.[69][70] Citizens of enemy states were subject to restrictions on travel, possession of equipment that might be used for espionage, and residence in areas likely to be invaded.[71] The government was reluctant to impose widespread internment. It rescinded a military decision of 7 August 1914 to intern all nationals of enemy states between the ages of 17 and 42, and focussed instead only on those suspected of being a threat to national security. By September, 10,500 aliens were being held, but between November 1914 and April 1915 few arrests were made and thousands of internees were actually released. Public anti-German sentiment, which had been building since October following reports of German atrocities in Belgium, peaked after the sinking of the RMS Lusitania on 7 May 1915. The incident prompted a week of rioting across the country, during which virtually every German-owned shop had its windows smashed. The reaction forced the government to implement a tougher policy on internment, as much for the aliens own safety as for the security of the country. All non-naturalised enemy nationals of military age were to be interned, while those over military age were to be repatriated, and by 1917 only a small number of enemy nationals were still residing at liberty.[72][73][74]

Armed forces[]

Army[]

The British Army during World War I was small in size when compared to the other major European powers. In 1914, the British had a small, largely urban English, volunteer force[75] of 400,000 soldiers, almost half of whom were posted overseas to garrison the immense British Empire. (In August 1914, 74 of the 157 infantry battalions and 12 of the 31 cavalry regiments were posted overseas.[1]: 504 ) This total included the Regular Army and reservists in the Territorial Force.[1]: 504 Together they formed the British Expeditionary Force (BEF),[76] for service in France and became known as the Old Contemptibles. The mass of volunteers in 1914–1915, popularly known as Kitchener's Army, was destined to go into action at the battle of the Somme.[1]: 504 In January 1916, conscription was introduced (initially of single men, extended to married men in May), and by the end of 1918, the army had reached its peak of strength of 4.5 million men.[1]: 504

[]

The Royal Navy at the start of the war was the largest navy in the world due, for the most part, to the Naval Defence Act 1889 and the two-power standard which called for the navy to maintain a number of battleships such as their strength was at least equal to the combined strength of the next two largest navies in the world, which at that point were France and Russia.[77]

The major part of the Royal Navy's strength was deployed at home in the Grand Fleet, with the primary aim of drawing the German High Seas Fleet into an engagement. No decisive victory ever came. The Royal Navy and the German Imperial Navy did come into contact, notably in the Battle of Heligoland Bight, and at the Battle of Jutland.[78] In view of their inferior numbers and firepower, the Germans devised a plan to draw part of the British fleet into a trap and put it into effect at Jutland in May 1916, but the result was inconclusive. In August 1916, the High Seas Fleet tried a similar enticement operation and was "lucky to escape annihilation".[79] The lessons learned by the Royal Navy at Jutland made it a more effective force in the future.[79]

In 1914, the navy had also formed the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division from reservists, and this served extensively in the Mediterranean and on the Western Front.[78] Almost half of the Royal Navy casualties during the War were sustained by this division, fighting on land and not at sea.[78]

British air services[]

At the start of the war, the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), commanded by David Henderson, was sent to France and was first used for aerial spotting in September 1914, but only became efficient when they perfected the use of wireless communication at Aubers Ridge on 9 May 1915. Aerial photography was attempted during 1914, but again only became effective the next year. In 1915 Hugh Trenchard replaced Henderson and the RFC adopted an aggressive posture. By 1918, photographic images could be taken from 15,000 feet (4,600 m), and interpreted by over 3,000 personnel. Planes did not carry parachutes until 1918, though they had been available since before the war.[80] On 17 August 1917, General Jan Smuts presented a report to the War Council on the future of air power. Because of its potential for the 'devastation of enemy lands and the destruction of industrial and populous centres on a vast scale', he recommended a new air service be formed that would be on a level with the army and navy. The formation of the new service however would make the under utilised men and machines of the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) available for action across the Western Front, as well as ending the inter-service rivalries that at times had adversely affected aircraft procurement. On 1 April 1918, the RFC and the RNAS were amalgamated to form a new service, the Royal Air Force (RAF).[81]

Recruitment and conscription[]

Particularly in the early stages of the war, many men, for a wide variety of reasons, decided to "join up" to the armed forces—by 5 September 1914, over 225,000 had signed up to fight for what became known as Kitchener's Army.[82] Over the course of the war, a number of factors contributed to recruitment rates, including patriotism, the work of the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee in producing posters, dwindling alternative employment opportunities, and an eagerness for adventure to escape humdrum routine.[82] Pals battalions, where whole battalions were raised from a small geographic area or employer, also proved popular. Higher recruitment rates were seen in England and Scotland, though in the case of the Welsh and Irish, political tensions tended to "put something of a blight upon enlistment".[82]

Recruitment remained fairly steady through 1914 and early 1915, but fell dramatically during the later years, especially after the Somme campaign, which resulted in 500,000 casualties. As a result, conscription was introduced for the first time in January 1916 for single men, and extended in May–June to all men aged 18 to 41 across England, Wales and Scotland, by way of the Military Service Acts.[82][84]

Urban centres, with their poverty and unemployment were favourite recruiting grounds of the regular British army. Dundee, where the female dominated jute industry limited male employment had one of the highest proportion of reservists and serving soldiers than almost any other British city.[85] Concern for their families' standard of living made men hesitate to enlist; voluntary enlistment rates went up after the government guaranteed a weekly stipend for life to the survivors of men who were killed or disabled.[86] After the introduction of conscription from January 1916, every region of the country, outside of Ireland, was affected.

The policy of relying on volunteers had sharply reduced the capacity of heavy industry to produce the munitions needed for the war. Historian R. J. Q. Adams reports that 19% of the men in the iron and steel industry entered the Army, 22% of the miners, 20% in the engineering trades, 24% in the electrical industries, 16% among small arms craftsmen, and 24% of the men who had been engaged in making high explosives.[87] In response critical industries were prioritised over the army ("reserved occupations"), including munitions, food production and merchant shipping.[82]

Conscription Crisis of 1918[]

In April 1918 legislation was brought forward which allowed for extension of conscription to Ireland.[82] Though this ultimately never materialised, the effect was "disastrous".[82] Despite significant numbers volunteering for Irish regiments,[82] the idea of enforced conscription proved unpopular. The reaction was based particularly on the fact that implementation of conscription in Ireland was linked to a pledged "measure of self-government in Ireland".[88] The linking of conscription and Home Rule in this way outraged the Irish parties at Westminster, who walked out in protest and returned to Ireland to organise opposition.[89] As a result, a general strike was called, and on 23 April 1918, work was stopped in railways, docks, factories, mills, theatres, cinemas, trams, public services, shipyards, newspapers, shops, and even official munitions factories. The strike was described as "complete and entire, an unprecedented event outside the continental countries".[90] Ultimately the effect was a total loss of interest in Home Rule and of popular support for the nationalist Irish Party who were defeated outright by the separatist republican Sinn Féin party in the December 1918 Irish general election, one of the precursors of the Anglo-Irish War.

Conscientious objectors[]

| External audio | |

|---|---|

The conscription legislation introduced the right to refuse military service, allowing for conscientious objectors to be absolutely exempted, to perform alternative civilian service, or to serve as a non-combatant in the army, according to the extent to which they could convince a Military Service Tribunal of the quality of their objection.[91] Around 16,500 men were recorded as conscientious objectors, with Quakers playing a large role.[82] Some 4,500 objectors were sent to work on farms to undertake "work of national importance", 7,000 were ordered non-combatant duties as stretcher bearers, but 6,000 were forced into the army, and when they refused orders, they were sent to prison, as in the case of the Richmond Sixteen.[92] Some 843 conscientious objectors spent more than two years in prison; ten died while there, seventeen were initially given the death penalty (but received life imprisonment) and 142 were imprisoned on life sentences.[93] Conscientious objectors who were deemed not to have made any useful contribution were disenfranchised for five years after the war.[91]

[]

At the start of the First World War, for the first time since the Napoleonic Wars, the population of the British Isles was in danger of attack from naval raids. The country also came under attack from air raids by zeppelins and fixed-wing aircraft, another first.[1]: 709 [94]

[]

The Raid on Yarmouth, which took place in November 1914, was an attack by the German Navy on the British North Sea port and town of Great Yarmouth. Little damage was done to the town itself, since shells only landed on the beach once German ships laying mines offshore were interrupted by British destroyers. One British submarine was sunk by a mine as it attempted to leave harbour and attack the German ships, while one German armoured cruiser was sunk after striking two mines outside its own home port.[95]

In December 1914, the German navy carried out attacks on the British coastal towns of Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby. The attack resulted in 137 fatalities and 593 casualties,[96] many of which were civilians. The attack made the German navy very unpopular with the British public, as an attack against British civilians in their homes. Likewise, the British Royal Navy was criticised for failing to prevent the raid.[97][98]

Bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft[]

In April 1916 a German battlecruiser squadron with accompanying cruisers and destroyers bombarded the coastal ports of Yarmouth and Lowestoft. Although the ports had some military importance, the main aim of the raid was to entice out defending ships which could then be picked off either by the battlecruiser squadron or by the full High Seas Fleet, which was stationed at sea ready to intervene if an opportunity presented itself. The result was inconclusive: nearby Royal Navy units were too small to intervene so largely kept clear of the German battlecruisers, and the German ships withdrew before the first British fast response battlecruiser squadron or the Grand Fleet could arrive.[99]

Air raids[]

German zeppelins bombed towns on the east coast, starting on 19 January 1915 with Great Yarmouth.[100] London was also hit later in the same year, on 31 May.[100] Propaganda supporting the British war effort often used these raids to their advantage: one recruitment poster claimed: "It is far better to face the bullets than to be killed at home by a bomb" (see image). The reaction from the public, however, was mixed; whilst 10,000 visited Scarborough to view the damage there, London theatres reported having fewer visitors during periods of "Zeppelin weather"—dark, fine nights.[100]

Throughout 1917 Germany began to deploy increasing numbers of fixed-wing bombers, the Gotha G.IV's first target being Folkestone on 25 May 1917, following this attack the number of airship raids decreased rapidly in favour of raids by fixed wing aircraft,[100] before Zeppelin raids were called off entirely. In total, Zeppelins dropped 6,000 bombs, resulting in 556 dead and 1,357 wounded.[101] Soon after the raid on Folkestone, the bombers began raids on London: one daylight raid on 13 June 1917 by 14 Gothas caused 162 deaths in the East End of London.[100] In response to this new threat, Major General Edward Bailey Ashmore, a RFC pilot who later commanded an artillery division in Belgium, was appointed to devise an improved system of detection, communication and control,[102] The system, called the Metropolitan Observation Service, encompassed the London Air Defence Area and would later extend eastwards towards the Kentish and Essex coasts. The Metropolitan Observation Service was fully operational until the late summer of 1918 (the last German bombing raid taking place on 19 May 1918).[103] During the war, the Germans carried out 51 airship raids and 52 fixed-wing bomber raids on England, which together dropped 280 tons of bombs. The casualties amounted to 1,413 killed, and 3,409 wounded.[104] The success of anti-air defence measures was limited; of the 397 aircraft that had taken part in raids, only 24 Gothas were shot down (though 37 more were lost in accidents), despite an estimated rate of 14,540 anti-air rounds per aircraft. Anti-zeppelin defences were more successful, with 17 shot down and 21 lost in accidents.[100]

Media[]

Propaganda[]

Propaganda and censorship were closely linked during the war.[105] The need to maintain morale and counter German propaganda was recognised early in the war and the War Propaganda Bureau was established under the leadership of Charles Masterman in September 1914.[105] The Bureau enlisted eminent writers such as H G Wells, Arthur Conan Doyle, Rudyard Kipling as well as newspaper editors. Until its abolition in 1917, the department published 300 books and pamphlets in 21 languages, distributed over 4,000 propaganda photographs every week, and circulated maps, cartoons, and lantern slides to the media.[106] Masterman also commissioned films about the war such as The Battle of the Somme, which appeared in August 1916, while the battle was still in progress as a morale-booster and in general it met with a favourable reception. The Times reported on 22 August 1916 that"

- Crowded audiences ... were interested and thrilled to have the realities of war brought so vividly before them, and if women had sometimes to shut their eyes to escape for a moment from the tragedy of the toll of battle which the film presents, opinion seems to be general that it was wise that the people at home should have this glimpse of what our soldiers are doing and daring and suffering in Picardy.[107]

The media—including the press, film. posters and billboards—were called to arms as propaganda for the masses. The manipulators favoured upper-and middle-class authoritative characters to educate the masses. At the time cinema audience were largely working class blokes. By contrast in World War Two, equality was a theme and class differentials were downplayed.[108]

Newspapers[]

Newspapers during the war were subject to the Defence of the Realm Act, which eventually had two regulations restricting what they could publish:[109] Regulation 18, which prohibited the leakage of sensitive military information, troop and shipping movements; and Regulation 27, which made it an offence to "spread false reports", "spread reports that were likely to prejudice recruiting", "undermine public confidence in banks or currency" or cause "disaffection to His Majesty".[109] Where the official failed (it had no statutory powers until April 1916), the newspaper editors and owners operated a ruthless self-censorship.[6] Having worked for government, press barons Viscount Rothermere,[110] Baron Beaverbrook (in a sea of controversy),[111] and Viscount Northcliffe[112] all received titles. For these reasons, it has been concluded that censorship, which at its height suppressed only socialist journals (and briefly the right wing The Globe) had less effect on the British press than the reductions in advertising revenues and cost increases which they also faced during the war.[6] One major loophole in the official censorship lay with parliamentary privilege, when anything said in Parliament could be reported freely.[109] The most infamous act of censorship in the early days of the war was the sinking of HMS Audacious in October 1914, when the press was directed not to report on the loss, despite the sinking being observed by passengers on the liner RMS Olympic and quickly reported in the American press.[113]

The most popular papers of the period included dailies such as The Times, The Daily Telegraph and The Morning Post, weekly newspapers such as The Graphic and periodicals like John Bull, which claimed a weekly circulation of 900,000.[114] The public demand for news of the war was reflected in the increased sales of newspapers. After the German Navy raid on Hartlepool and Scarborough, the Daily Mail devoted three full pages to the raid and the Evening News reported that The Times had sold out by a quarter past nine in the morning, even with inflated prices.[115] The Daily Mail itself increased in circulation from 800,000 a day in 1914 to 1.5 million by 1916.[6]

News magazines[]

The public's thirst for news and information was in part satisfied by news magazines, which were dedicated to reporting the war. They included amongst others The War Illustrated, The Illustrated War News, and The War Pictorial, and were lavishly filled with photographs and illustrations, regardless of their target audience. Magazines were produced for all classes, and ranged both in price and tone. Many otherwise famous writers contributed towards these publications, of which H.G. Wells, Arthur Conan Doyle and Rudyard Kipling were three examples. Editorial guidelines varied; in cheaper publications especially it was considered more important to create a sense of patriotism than to relay up-to-the-minutes news of developments of the front. Stories of German atrocities were commonplace.[116]

Motion pictures[]

The 1916 British film The Battle of the Somme, by two official cinematographers, Geoffrey Malins and John McDowell, combined documentary and propaganda, seeking to give the public an impression of what trench warfare was like. Much of the film was shot on location at the Western Front in France; it had a powerful emotional impact. It was watched by some 20 million people in Britain in its six weeks of exhibition, making it what the critic Francine Stock called "one of the most successful films of all time".[117][118]

Music[]

On 13 August 1914, the Irish regiment the Connaught Rangers were witnessed singing "It's a Long Way to Tipperary" as they marched through Boulogne by the Daily Mail correspondent George Curnock, who reported the event in that newspaper on 18 August 1914. The song was then picked up by other units of the British Army. In November 1914, it was sung in a pantomime by the well-known music hall singer Florrie Forde, which helped contribute to its worldwide popularity.[119] Another song from 1916, which became very popular as a music hall and marching song, boosting British morale despite the horrors of that war, was "Pack Up Your Troubles in Your Old Kit-Bag".[120]

War poems[]

There was also a notable group of war poets who wrote about their own experiences of war, which caught the public attention. Some died on active service, most famously Rupert Brooke, Isaac Rosenberg, and Wilfred Owen, while some, such as Siegfried Sassoon survived. Themes of the poems included the youth (or naivety) of the soldiers, and the dignified manner in which they fought and died. This is evident in lines such as "They fell with their faces to the foe", from the "Ode of Remembrance" taken from Laurence Binyon's For the Fallen, which was first published in The Times in September 1914.[121] Female poets such as Vera Brittain also wrote from the home front, to lament the losses of brothers and lovers fighting on the front.[122]

Economy[]

On the whole the British successfully managed the economics of the war. There had been no prewar plan for mobilization of economic resources. Controls were imposed slowly, as one urgent need followed another.[123] With the City of London the world's financial capital, it was possible to handle finances smoothly; in all Britain spent 4 million pounds everyday on the war effort.[124]

The economy (in terms of GDP) grew about 14% from 1914 to 1918 despite the absence of so many men in the services; by contrast the German economy shrank 27%. The War saw a decline of civilian consumption, with a major reallocation to munitions. The government share of GDP soared from 8% in 1913 to 38% in 1918 (compared to 50% in 1943).[125][126] The war forced Britain to use up its financial reserves and borrow large sums from private and government creditors in the United States.[127] Shipments of American raw materials and food allowed Britain to feed itself and its army while maintaining productivity. The financing was generally successful,[128] as the City's strong financial position minimized the damaging effects of inflation, as opposed to much worse conditions in Germany.[129] Overall consumer consumption declined 18% from 1914 to 1919.[130] Women were available and many entered munitions factories and took other home front jobs vacated by men.[131][132]

Scotland specialized in providing manpower, ships, machinery, food (particularly fish) and money. Its shipbuilding industry expanding by a third.[133]

Rationing[]

In line with its "business as usual" policy, the government was initially reluctant to try to control the food markets.[134] It fought off efforts to try to introduce minimum prices in cereal production, though relenting in the area of controlling of essential imports (sugar, meat and grains). When it did introduce changes, they were only limited in their effect. In 1916, it became illegal to consume more than two courses whilst lunching in a public eating place or more than three for dinner; fines were introduced for members of the public found feeding the pigeons or stray animals.[64]

In January 1917, Germany started using U-boats (submarines) in order to sink Allied and later neutral ships bringing food to the country in an attempt to starve Britain into defeat under their unrestricted submarine warfare programme. One response to this threat was to introduce voluntary rationing in February 1917,[64] a sacrifice promoted by the King and Queen themselves.[135] Bread was subsidised from September that year; prompted by local authorities taking matters into their own hands, compulsory rationing was introduced in stages between December 1917 and February 1918,[64] as Britain's supply of wheat stores decreased to just six weeks worth.[136] For the most part it benefited the health of the country,[64] through the levelling of consumption of essential foods. To operate rationing, ration books were introduced on 15 July 1918 for butter, margarine, lard, meat, and sugar.[137] During the war, average calorific intake decreased only three percent, but protein intake six percent.[64]

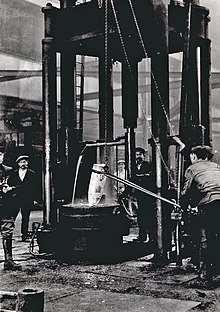

Industry[]

Total British production fell by ten percent over the course of the war; there were, however, increases in certain industries such as steel.[7] Although Britain faced a highly contentious Shell Crisis of 1915 With severe shortages of artillery shells on the Western Front.[138] New leadership was called for. In 1915, a powerful new Ministry of Munitions under David Lloyd George was formed to control munitions production.[139]

The Government's policy, according to historian and Conservative politician J. A. R. Marriott, was that:

- No private interest was to be permitted to obstruct the service, or imperil the safety, of the State. Trade Union regulations must be suspended; employers' profits must be limited, skilled men must fight, if not in the trenches, in the factories; man-power must be economized by the dilution of labour and the employment of women; private factories must pass under the control of the State, and new national factories be set up. Results justified the new policy: the output was prodigious; the goods were at last delivered.[140]

By April 1915, just two million rounds of shells had been sent to France; by the end of the war the figure had reached 187 million,[141] and a year's worth of pre-war production of light munitions could be completed in just four days by 1918. Aircraft production in 1914 provided employment for 60,000 men and women; by 1918 British firms employed over 347,000.[7]

Labour[]

Industrial production of munitions was a central feature of the war, and with a third of the men in the labour force moved into the military, demand was very high for industrial labour. Large numbers of women were employed temporarily.[142] Most trade unions gave strong support to the war effort, cutting back on strikes and restrictive practices. However the coal miners and engineers were less enthusiastic.[143] Trade unions were encouraged as membership grew from 4.1 million in 1914 to 6.5 million in 1918, peaking at 8.3 million in 1920 before relapsing to 5.4 million in 1923.[144] In 1914, 65% of union members had been associated with the Trades Union Congress (TUC) rising to 77% in 1920. Women were grudgingly admitted to the trade unions. Looking at a union of unskilled workers, Cathy Hunt concludes its regard for women workers, "was at best inconsistent and at worst aimed almost entirely at improving and protecting working conditions for its male members."[145] Labour's prestige had never been higher, and it systematically placed its leaders into Parliament.[146]

The Munitions of War Act 1915 followed the Shell Crisis of 1915 when supplies of material to the front became a political issue. The Act forbade strikes and lockouts and replaced them with compulsory arbitration. It set up a system of controlling war industries, and established munitions tribunals that were special courts to enforce good working practices. It suspended, for the duration, restrictive practices by trade unions. It tried to control labour mobility between jobs. The courts ruled the definition of munitions was broad enough to include textile workers and dock workers. The 1915 act was repealed in 1919, but similar legislation took effect during the Second World War.[147][148][149]

It was only as late as December 1917 that a War Cabinet Committee on Manpower was established, and the British government refrained from introducing compulsory labour direction (though 388 men were moved as part of the voluntary National Service Scheme). Belgian refugees became workers, though they were often seen as "job stealers". Likewise, the use of Irish workers, because they were exempt from conscription, was another source of resentment.[150] Worried about the impact of the dilution of labour caused by bringing external groups into the main labour pool, workers in some areas turned to strike action. The efficiency of major industries improved markedly during the war. For example, the Singer Clydebank sewing machine factory received over 5000 government contracts, and made 303 million artillery shells, shell components, fuzes, and airplane parts, as well as grenades, rifle parts, and 361,000 horseshoes. Its labour force of 14,000 was about 70 percent female at war's end.[151]

Energy[]

Energy was a critical factor for the British war effort. Most of the energy supplies came from coal mines in Britain, where the issue was labour supply. Critical however was the flow of oil for ships, lorries and industrial use. There were no oil wells in Britain so everything was imported. The U.S. pumped two-thirds of the world's oil. In 1917, total British consumption was 827 million barrels, of which 85 percent was supplied by the United States, and 6 percent by Mexico.[152] The great issue in 1917 was how many tankers would survive the German U-boats. Convoys and the construction of new tankers solved the German threat, while tight government controls guaranteed that all essential needs were covered. An Inter-Allied Petroleum Conference allocated American supplies to Britain, France and Italy.[153]

Fuel oil for the Royal Navy was the highest priority. In 1917, the Royal Navy consumed 12,500 tons a month, but had a supply of 30,000 tons a month from the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, using their oil wells in Persia.[154]

Social change[]

Variously throughout the war, serious shortage of able-bodied men ("manpower") occurred in the country, and women were required to take on many of the traditional male roles, particularly in the area of arms manufacture; though this was only significant in the later years of the war, since unemployed men were often prioritised by employers.[8] Women both found work in the munitions factories (as "munitionettes") despite initial trade union opposition, which directly helped the war effort, but also in the Civil Service, where they took men's jobs, releasing them for the front. The number of women employed by the service increased from 33,000 in 1911 to over 102,000 by 1921.[155] The overall increase in female employment is estimated at 1.4 million, from 5.9 to 7.3 million,[8] and female trade union membership increased from 357,000 in 1914 to over a million by 1918—an increase of 160 percent.[155] Beckett suggests that most of these were working class women going into work at a younger age than they would otherwise have done, or married women returning to work. This taken together with the fact that only 23 percent of women in the munitions industry were actually doing men's jobs, would limit substantially the overall impact of the war on the long-term prospects of the working woman.[8]

When the government targeted women early in the war focused on extending their existing roles – helping with Belgian refugees, for example—but also on improving recruitment rates amongst men. They did this both through the so-called "Order of the White Feather" and through the promise of home comforts for the men while they were at the front. In February 1916, groups were set up and a campaign started to get women to help in agriculture and in March 1917, the Women's Land Army was set up. One goal was to attract middle-class women who would act as models for patriotic engagement in nontraditional duties. However the uniform of the Women's Land Army included male overalls and trousers, which sparked debate on the propriety of such cross-dressing. The government responded with rhetoric that explicitly feminized the new roles.[156] In 1918, the Board of Trade estimated that there were 148,000 women in agricultural employment, though a figure of nearly 260,000 has also been suggested.[8]

The war also caused a split in the British suffragette movement, with the mainstream, represented by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel's Women's Social and Political Union, calling a 'ceasefire' in their campaign for the duration of the war. In contrast, more radical suffragettes, like the Women's Suffrage Federation run by Emmeline's other daughter, Sylvia, continued their (at times violent) struggle. Women were also allowed to join the armed forces in a non-combatant role[8] and by the end of the War 80,000 women had joined the armed forces in auxiliary roles such as nursing and cooking.[157]

Following the war, millions of returning soldiers were still not entitled to vote.[158] This posed another dilemma for politicians since they could be seen to be withholding the vote from the very men who had just fought to preserve the British democratic political system. The Representation of the People Act 1918 attempted to solve the problem, enfranchising all adult males as long as they were over 21 years old and were resident householders.[158] It also gave the vote to women over 30 who met minimum property qualifications. The enfranchisement of this latter group was accepted as recognition of the contribution made by women defence workers,[158] though the actual feelings of members of parliament (MPs) at the time is questioned.[8] In the same year the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act 1918 allowed women over 21 to stand as MPs.[159]

The new coalition government of 1918 charged itself with the task of creating a "land fit for heroes", from a speech given in Wolverhampton by David Lloyd George on 23 November 1918, where he stated "What is our task? To make Britain a fit country for heroes to live in."[160] More generally, the war has been credited, both during and after the conflict, with removing some of the social barriers that had pervaded Victorian and Edwardian Britain.[2]

Regional conditions[]

The War had a profound influence upon rural areas, as the U-boat blockade required the government to take full control of the food chain, as well as agricultural labour. Cereal production was a high priority, and the Corn Production Act 1917 guaranteed prices, regulated wage rates, and required farmers to meet efficiency standards. The government campaigned heavily for turning marginal land into cropland.[161][162][163] The Women's Land Army brought in 23,000 young women from the towns and cities to milk cows, pick fruit and otherwise replace the men who joined the services.[164] More extensive use of tractors and machinery also replaced farm labourers. However, there was a shortage of both men and horses on the land by late 1915. County War Agricultural Executive Committees reported that the continued removal of men was undercutting food production because of the farmers' belief that operating a farm required a set number of men and horses.[165]

Kenneth Morgan argues that, "the overwhelming mass of the Welsh people cast aside their political and industrial divisions and threw themselves into the war with gusto." Intellectuals and ministers actively promoted the war spirit. With 280,000 men enrolled in the services (14% of the population), the proportionate effort in Wales outstripped both England and Scotland.[166] However Adrian Gregory points out that the Welsh coal miners, while officially supporting the war effort, refused the government request to cut short their vacation time. After some debate, the miners agreed to extend the working day.[167]

Scotland's distinctive characteristics have attracted significant attention from scholars.[168] Daniel Coetzee shows it supported the war effort with widespread enthusiasm.[169] It especially provided manpower, ships, machinery, food (particularly fish) and money, engaging with the conflict with some enthusiasm.[170] With a population of 4.8 million in 1911, Scotland sent 690,000 men to the war, of whom 74,000 died in combat or from disease, and 150,000 were seriously wounded.[171][172] Scottish urban centres, with their poverty and unemployment were favourite recruiting grounds of the regular British army, and Dundee, where the female dominated jute industry limited male employment had one of the highest proportion of reservists and serving soldiers than almost any other British city.[173] Concern for their families' standard of living made men hesitate to enlist; voluntary enlistment rates went up after the government guaranteed a weekly stipend for life to the survivors of men who were killed or disabled.[174] After the introduction of conscription from January 1916 every part of the country was affected. Occasionally Scottish troops made up large proportions of the active combatants, and suffered corresponding loses, as at the Battle of Loos, where there were three full Scots divisions and other Scottish units.[85] Thus, although Scots were only 10 per cent of the British population, they made up 15 per cent of the national armed forces and eventually accounted for 20 per cent of the dead.[175] Some areas, like the thinly populated Island of Lewis and Harris suffered some of the highest proportional losses of any part of Britain.[85] Clydeside shipyards and the nearby engineering shops were the major centers of war industry in Scotland. In Glasgow, radical agitation led to industrial and political unrest that continued after the war ended.[176]

Casualties[]

In the post war publication Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire During the Great War 1914–1920 (The War Office, March 1922), the official report lists 908,371 'soldiers' as being either killed in action, dying of wounds, dying as prisoners of war or missing in action in the World War. (This is broken down into Britain and its colonies 704,121; British India 64,449; Canada 56,639; Australia 59,330; New Zealand 16,711; South Africa 7,121.)[11] Listed separately were the Royal Navy (including the Royal Naval Air Service until 31 March 1918) war dead and missing of 32,287 and the Merchant Navy war dead of 14,661.[11] The figures for the Royal Flying Corps and the nascent Royal Air Force were not given in the War Office report.[11]

A second publication, Casualties and Medical Statistics (1931), the final volume of the Official Medical History of the War, gives British Empire Army losses by cause of death.[12] The total losses in combat from 1914 to 1918 were 876,084, which included 418,361 killed, 167,172 died of wounds, 113,173 died of disease or injury, 161,046 missing presumed dead and 16,332 died as a prisoner of war.[12]

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission lists 888,246 imperial war dead (excluding the dominions, which are listed separately). This figure includes identified burials and those commemorated by name on memorials; there are an additional 187,644 unidentified burials from the Empire as a whole.[177]

The civilian death rate exceeded the prewar level by 292,000, which included 109,000 deaths due to food shortages and 183,577 from Spanish flu.[11] The 1922 War Office report detailed the deaths of 1,260 civilians and 310 military personnel due to air and sea bombardment the home islands.[178] Losses at sea were 908 civilians and 63 fisherman killed by U-boat attacks.[179]

With a population of 4.8 million in 1911, Scotland sent 690,000 men to the war, of whom 74,000 died in combat or from disease, and 150,000 were seriously wounded.[171][172] At times Scottish troops made up large proportions of the active combatants, and suffered corresponding loses, as at the Battle of Loos, where there were three full Scots divisions and other Scottish units.[85] Thus, although Scots were only 10 per cent of the British population, they made up 15 per cent of the national armed forces and eventually accounted for 20 per cent of the dead.[175] Some areas, like the thinly populated Island of Lewis and Harris suffered some of the highest proportional losses of any part of Britain.[85] Clydeside shipyards and the engineering shops of west-central Scotland became the most significant centre of shipbuilding and arms production in the Empire. In the Lowlands, particularly Glasgow, poor working and living conditions led to industrial and political unrest.[175]

Legacy and memory[]

The horrors of the Western Front as well as Gallipoli and Mesopotamia were seared into the collective consciousness of the twentieth century. To a large extent the understanding of the war in popular culture focused on the first day of the Battle of the Somme. Historian A. J. P. Taylor argued, "The Somme set the picture by which future generations saw the First World War: brave helpless soldiers; blundering obstinate generals; nothing achieved."[180]

Images of trench warfare became iconic symbols of human suffering and endurance. The post-war world had many veterans who were maimed or damaged by shell shock. In 1921 1,187,450 men were in receipt of pensions for war disabilities, with a fifth of these having suffered serious loss of limbs or eyesight, paralysis or lunacy.[181]

The war was a major economic catastrophe as Britain went from being the world's largest overseas investor to being its biggest debtor, with interest payments consuming around 40 percent of the national budget.[182] Inflation more than doubled between 1914 and its peak in 1920, while the value of the Pound Sterling fell by 61.2 percent. Reparations in the form of free German coal depressed the local industry, precipitating the 1926 General Strike.[182] During the war British private investments abroad were sold, raising £550 million. However, £250 million new investment also took place during the war. The net financial loss was therefore approximately £300 million; less than two years investment compared to the pre-war average rate and more than replaced by 1928.[183] Material loss was "slight": the most significant being 40 percent of the British merchant fleet sunk by German U-boats. Most of this was replaced in 1918 and all immediately after the war.[184] The military historian Correlli Barnett has argued that "in objective truth the Great War in no way inflicted crippling economic damage on Britain" but that the war only "crippled the British psychologically" (emphasis in original).[185]

Less concrete changes include the growing assertiveness of the Dominions within the British Empire. Battles such as Gallipoli for Australia and New Zealand,[186] and Vimy Ridge for Canada led to increased national pride and a greater reluctance to remain subordinate to London.[14] These battles were often portrayed favourably in these nations' propaganda as symbolic of their power during the war.[14][186] The war released pent-up indigenous nationalism, as populations tried to take advantage of the precedent set by the introduction of self-determination in eastern Europe. Britain was to face unrest in Ireland (1919–21), India (1919), Egypt (1919–23), Palestine (1920–21) and Iraq (1920) at a time when they were supposed to be demilitarising.[13] Nevertheless, Britain's only territorial loss came in Ireland,[13] where the delay in finding a resolution to the home rule issue, along with the 1916 Easter Rising and a failed attempt to introduce conscription in Ireland, increased support for separatist radicals, and led indirectly to the outbreak of the Irish War of Independence in 1919.[187]

Further change came in 1919. With the Treaty of Versailles, London took charge of an additional 1,800,000 square miles (4,700,000 km2) and 13 million new subjects.[188] The colonies of Germany and the Ottoman Empire were redistributed to the Allies (including Australia, New Zealand and South Africa) as League of Nations mandates, with Britain gaining control of Palestine and Transjordan, Iraq, parts of Cameroon and Togo, and Tanganyika.[189] Indeed, the British Empire reached its territorial peak after the settlement.[13]

See also[]

- Diplomatic history of World War I

- British home army in the First World War

- Imperial German plans for the invasion of the United Kingdom

- Opposition to World War I

- The Women's Peace Crusade

References[]

- ^ a b c d e f Tucker, Spencer C.; Roberts, Priscilla (2005). The Encyclopedia of World War I: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-420-2.

- ^ Gregory (2008); Pennell (2012)

- ^ a b Baker (1921) p 21

- ^ a b c d Trueman, Chris. "Total war". History Learning Site. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ a b c d Beckett (2007), pp 394–395

- ^ a b c Beckett (2007), pp 341–343

- ^ a b c d e f g Beckett (2007), pp 455–460

- ^ Braybon (1990)

- ^ Braybon (2005)

- ^ a b c d e The War Office (1922). Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire during the Great War, 1914-1920 (Report). The War Office. p. 339.

- ^ a b c Mitchell (1931), p 12

- ^ a b c d Beckett (2007), p 564

- ^ a b c Pierce (1992), p 5

- ^ Adrian Gregory (2008). The Last Great War: British Society and the First World War. Cambridge UP. p. 10. ISBN 9781107650862.

- ^ Bentley B. Gilbert, "Pacifist to interventionist: David Lloyd George in 1911 and 1914. Was Belgium an issue?." Historical Journal 28.4 (1985): 863–885.

- ^ Zara S. Steiner, Britain and the origins of the First World War (1977) pp 235–237.

- ^ Steiner, Britain and the origins of the First World War (1977) pp 230–235.

- ^ Clark, Christopher (19 March 2013). The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-219922-5.

- ^ Robert Blake, The Decline of Power: 1915–1964 (1985), p.3

- ^ Blake, The Decline of Power (1985), p.3

- ^ Manchester Guardian 1 May 1915, editorial, in Trevor Wilson (1966). The Downfall of the Liberal Party, 1914–1935. p. 51. ISBN 9780571280223.

- ^ Barry McGill, "Asquith's Predicament, 1914–1918." Journal of Modern History 39.3 (1967): 283–303. in JSTOR

- ^ A.J.P. Taylor (1965). English History, 1914–1945. p. 17. ISBN 9780198217152.

- ^ Barry McGill, "Asquith's Predicament, 1914–1918," Journal of Modern History (1967) 39#3 pp. 283–303 in JSTOR

- ^ John M. McEwen, "The Struggle for Mastery in Britain: Lloyd George versus Asquith, December 1916." Journal of British Studies 18#1 (1978): 131–156.

- ^ John Grigg, Lloyd George: War Leader 1916–1918 (2002) vol 4 pp 1–30

- ^ A. J. P. Taylor, English History, 1914–1945 (1965) pp 73–99

- ^ The Oxford Library of Words and Phrases. Oxford University Press. 1981. p. 71.

- ^ Beckett (2007), pp 499–500

- ^ A. J. P. Taylor, English History, 1914–1945 (1965) pp 100–106

- ^ John Grigg, Lloyd George: War Leader 1916–1918 (2002) vol 4 pp 478–83

- ^ Alan J. Ward, "Lloyd George and the 1918 Irish Conscription Crisis," Historical Journal (1974) 17#1 pp. 107–129 in JSTOR

- ^ Grigg, Lloyd George vol 4 pp 465–88

- ^ John Gooch, "The Maurice Debate 1918," Journal of Contemporary History (1968) 3#4 pp. 211–228 in JSTOR

- ^ John Grigg, Lloyd George: War leader, 1916–1918 (London: Penguin, 2002), pp 489–512

- ^ A. J. P. Taylor, English History, 1914–1945 (1965) pp 108–11

- ^ George H. Cassar, Lloyd George at War, 1916–1918 (2009) p 351 online at JSTOR

- ^ Trevor Wilson, "The Coupon and the British General Election of 1918," Journal of Modern History, (1964) 36#1 pp. 28–42 in JSTOR

- ^ Wilson, The Downfall of the Liberal Party: 1914–1935 (1966) pp 135–85

- ^ Martin Horn, Britain, France, and the financing of the First World War (2002).

- ^ Peter Dewey, War and progress: Britain 1914–1945 (1997) pp 28–31.

- ^ Anthony J. Arnold, "‘A paradise for profiteers’? The importance and treatment of profits during the First World War." Accounting History Review 24#2–3 (2014): 61–81.

- ^ Mark Billings and Lynne Oats, "Innovation and pragmatism in tax design: Excess Profits Duty in the UK during the First World War." Accounting History Review 24#2–3 (2014): 83–101.

- ^ A. J. P. Taylor, English History 1914–1945 (1965) pp 40 – 41.

- ^ M. J. Daunton, "How to Pay for the War: State, Society and Taxation in Britain, 1917–24," English Historical Review (1996) 111# 443 pp. 882–919

- ^ Nicolson (1952), p 308

- ^ "The Royal Family name". Official web site of the British monarchy. Archived from the original on 15 February 2009. Retrieved 8 May 2009.

- ^ Nicolson (195), p 310

- ^ "Titles Deprivation Act 1917". office of public sector information. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- ^ At George's wedding in 1893, The Times claimed that the crowd may have confused Nicholas with George, because their beards and uniforms made them look alike (The Times 7 July 1893, p 5)

- ^ Nicolson (1952), p 301

- ^ Andrew Roberts (2000). The House of Windsor. U of California Press. p. 30. ISBN 9780520228030.

- ^ Roberts (2000), p 41

- ^ Ziegler (1991), p 111

- ^ Duke of Windsor (1998), p 140

- ^ Bradford (1989), pp 55–76

- ^ Imperial War Museum. "Princess Mary's Gift to the Troops, Christmas 1914". archive.iwm.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ^ Thornton-Cook (1977), p.229

- ^ Beckett (2007), Chronology

- ^ a b Beckett (2007), p 348

- ^ FitzRoy, Almeric William, Clerk of the Privy Council (14 August 1914). "Part 1: General Regulations" (PDF). The London Gazette (28870). p. 3.

It shall be lawful for the competent naval or military authority ... (a) to take possession of any land ... (b) to take possession of any buildings or other property

CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ FitzRoy, Almeric William, Clerk of the Privy Council (14 August 1914). "Part 2: Regulations specially designed to prevent persons communicating with the enemy ..." (PDF). The London Gazette (28870). p. 4.

No person shall trespass on any railway, or loiter under or near any bridge, viaduct, or culvert, over which a railway passes.

CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f Beckett (2007), pp 380–382

- ^ FitzRoy, Almeric William, Clerk of the Privy Council (14 August 1914). "Part 2: Regulations specially designed to prevent persons communicating with the enemy ..." (PDF). The London Gazette (28870). p. 4.

No person shall ... communicate any information with respect to the movement or disposition of any of the forces, ships, or war materials ... or with respect to the plans of any naval or military operations

CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Beckett (2007), p 383

- ^ "Treachery Bill". Hansard. Retrieved 13 May 2009.

- ^ "British Army: Courts Martial: First World War, 1914–1918". National Archives. Archived from the original on 6 October 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2009.

- ^ Pearsall

- ^ Panayi 2014 p. 50

- ^ Panayi 2014 pp. 46–52

- ^ Panayi 2014 pp. 57, 71–78

- ^ Panayi 2013 p. 50

- ^ Denness p. 178

- ^ Beckett (2007), p 289

- ^ Chandler (2003), p 211

- ^ Sondhaus (2001), p 161

- ^ a b c "The First World War and the Inter-war years 1914–1939". Royal Navy. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2009.

- ^ a b "Battle of Jutland 1916". Royal Navy. Archived from the original on 25 October 2010. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

- ^ Beckett (2007), p 254

- ^ "The Royal Air Force History". Royal Air Force. Archived from the original on 9 December 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Beckett (2007), pp 291–5

- ^ Te Papa (the Museum of New Zealand)'s description of the poster.

- ^ Strachan, Hew. "BBC – History – British History in depth: Overview: Britain and World War One, 1901 – 1918". BBC History. Retrieved 13 May 2009.

- ^ a b c d e B. Lenman and J., Mackie, A History of Scotland (Penguin, 1991)

- ^ D. Coetzee, "A life and death decision: the influence of trends in fertility, nuptiality and family economies on voluntary enlistment in Scotland, August 1914 to December 1915", Family and Community History, November 2005, vol. 8 (2), pp. 77–89.

- ^ R. J. Q. Adams, "Delivering the Goods: Reappaising the Ministry of Munitions: 1915–1916." Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies (1975) 7#3 pp: 232–244 at p. 238 in JSTOR

- ^ Adams (1999), p 266

- ^ (1974). Lloyd George and the 1918 Irish Conscription Crisis. The Historical Journal, Vol. XVII, no. 1.

- ^ Cahill, Liam (1990). Forgotten Revolution: Limerick Soviet, 1919. O'Brien Press. ISBN 978-0-86278-194-1.

- ^ a b Taylor (2001), p 116

- ^ Silence in castle to honour First World War conscientious objectors dated 25 June 2013 at thenorthernecho.co.uk, accessed 19 October 2014

- ^ Beckett (2007), p 507

- ^ Corbett Julian. "Yorkshire Coast Raid, 15–16 December 1914". Official History of the War, Naval Operations Vol. II. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- ^ Massie (2004), pp 309–311

- ^ His Majesty's stationery Office (1922), pp 674–677

- ^ "Damage by German Raids". UK Parliament "Hansard". Retrieved 13 May 2009.

- ^ "German Attacks on Unfortified Towns". UK Parliament "Hansard". Retrieved 13 May 2009.

- ^ Tucker, Wood & Murphy (2005), P.193

- ^ a b c d e f Beckett (2007), pp 258–261

- ^ Powers (1976), pp 50–51

- ^ Bourne (2001), p 10

- ^ Bourne (2001), p 20

- ^ "Air Raids". National Archives. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- ^ a b "Espionage, propaganda and censorship". National Archives. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- ^ D. G. Wright, "The Great War, Government Propaganda and English 'Men Of Letters' 1914–16." Literature and History 7 (1978): 70+.

- ^ 'War's Realities on the Cinema', The Times, London, 22 August 1916, p 3

- ^ Stella Hockenhull, "Everybody’s business: Film, food and victory in the first world war." Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 35.4 (2015): 579-595. online

- ^ a b c Paddock (2004), p 22

- ^ "No. 31427". The London Gazette. 1 July 1919. p. 8221.

- ^ McCreery (2005), pp 26–27

- ^ "No. 30533". The London Gazette. 19 February 1918. p. 2212.

- ^ Paddock (2004), p 24

- ^ Paddock (2004), p 16

- ^ Paddock (2004), p 34

- ^ "War Weeklies". Time. 25 September 1939. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 12 June 2009.

- ^ Smither, R.B.N. (2008). The Battle of the Somme (DVD viewing guide) (PDF) (2nd rev. ed.). Imperial War Museum. ISBN 978-0-90162-794-0.

- ^ Stock, Francine. "Why was the Battle of the Somme film bigger than Star Wars?". BBC. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ Cryer (2009), p 188

- ^ Shepherd (2003), p 390

- ^ The Times on 21 September 1914.

- ^ Singh, Anita (13 February 2009). "Vera Brittain to be subject for film". Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ^ William Ashworth, An Economic History of England, 1870–1939 (1960) pp 265–84.

- ^ Tom Kington (13 October 2009). "Recruited by MI5: the name's Mussolini. Benito Mussolini". The Guardian.

- ^ David Stevenson (2011). With Our Backs to the Wall: Victory and Defeat in 1918. Harvard U.P. p. 370. ISBN 9780674062269.

- ^ Niall Ferguson, The Pity of War (1998) p 249

- ^ Steven Lobell, "The Political Economy of War Mobilization: From Britain's Limited Liability to a Continental Commitment," International Politics (2006) 43#3 pp 283–304

- ^ M. J. Daunton, "How to Pay for the War: State, Society and Taxation in Britain, 1917–24," English Historical Review (1996) 111# 443 pp. 882–919 in JSTOR

- ^ T. Balderston, "War finance and inflation in Britain and Germany, 1914–1918," Economic History Review (1989) 42#2 p p 222–244. in JSTOR