Hope Downs mine

| Location | |

|---|---|

Hope Downs 4 mine Location in Australia | |

| Location | Pilbara |

| State | Western Australia |

| Country | Australia |

| Coordinates | 23°08′42″S 119°34′19″E / 23.144968°S 119.572064°ECoordinates: 23°08′42″S 119°34′19″E / 23.144968°S 119.572064°E |

| Production | |

| Products | Iron ore |

| Production | 30 million tonnes/annum |

| History | |

| Opened | 2007 |

| Owner | |

| Company | Rio Tinto Iron Ore (50%) Hancock Prospecting (50%) |

| Website | Rio Tinto Iron Ore website Hancock Prospecting website |

The Hope Downs mine is an iron ore mining complex located in the Pilbara region of Western Australia. It comprises four large open-pit mines (Hope 1 North, Hope 1 South, Hope 4 and Baby Hope). The mines are co-owned by the Hancock Group and Rio Tinto, and the complex was named after Hope Hancock.[1]

After the establishment of successful operations at Hope 1 North and South from 2007 onwards, Hope Downs 4 was developed, commencing production in 2013. Hope 4 is about 30 kilometres (19 mi) north of Newman, and had a reserve of 162Mt as at 2016. Production at Baby Hope started in 2018.[1]

The Hamersley Range, where the mine is located, contains 80 percent of all identified iron ore reserves in Australia and is one of the world's major iron ore provinces.[2]

In the calendar year 2009, the combined Pilbara operations produced 202 million tonnes of iron ore, a 15 percent increase from 2008.[3] The Pilbara operations accounted for almost 13 percent of the world's 2009 iron ore production of 1.59 billion tonnes.[4][5] In 2010, the project leases were estimated to have 1,450 million tonnes of mineable ore and the mines to have an expected life of more than 30 years.[6]

Overview[]

Rio Tinto iron ore operations in the Pilbara began in 1966.[7] Exploration work through Hancock Prospecting at the Hope Downs 4 deposit began in 1992. Hancock unsuccessfully tried to develop the project with a number of partners, briefly rumored to be planning to join up with the Fortescue Metals Group in 2005, who was then developing its Cloud Break mine in the region.[8] The development of the project suffered further delays when attempts to gain access to BHP Billiton's rail network failed, burdening the project with a further A$1 billion in cost to construct rail and port infrastructure.[9] Eventually, in July 2005, Rio Tinto became a partner in the project instead, making thereby the construction of major infrastructure unnecessary, and, after spending A$1.3 billion, the mine moved into production in November 2007.[10] The mine has an annual production capacity of 30 million tonnes of iron ore, sourced from open-pit operations. The ore is processed on site before being loaded onto rail.[11]

In the first half of 2009, Rio Tinto upgraded the mine from an annual production of 22 million tonnes to 30 million tonnes.[12]

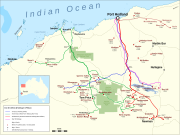

Ore from the mine is then transported to the coast through the Hamersley & Robe River railway, where it is loaded onto ships.[13] The 30 kilometre spur line connecting the mine with Rio Tinto's existing railway system was named "Lang Hancock Railway" in honor of Lang Hancock, founder of Hancock Prospecting and discoverer of the iron ore deposit.[14]

The mine's workforce is on a fly-in fly-out roster.[11] In the calendar year 2009, the mine employed 787 people, an increase in comparison to 2008, when it only employed 453.[12]

Rio Tinto declared its intention to expand the mine, spending a further A$1.78 billion on the Hope Downs 4 project, scheduled to produce 15 million tonnes of iron ore annually by 2013.[15][16]

In popular culture[]

In June 2018, Australian indie rock band Rolling Blackouts Coastal Fever named their debut album Hope Downs after the vast mining complex, explaining that it evoked the notion of "standing at the edge of the void of the big unknown, and finding something to hold on to."[17]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Hope Downs". Hancock Prospecting Pty Ltd. 23 July 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Iron fact sheet - Australian Resources and Deposits Archived 2011-02-18 at the Wayback Machine Geoscience Australia website, accessed: 7 November 2010

- ^ Preparing for the future Archived 2011-07-15 at the Wayback Machine Rio Tinto presentation, published: 23 March 2010, accessed: 7 November 2010

- ^ Global iron-ore production falls 6,2% in 2009 - Unctad report miningweekly.com, published: 30 July 2010, accessed: 7 November 2010

- ^ Production of iron ore fell in 2009, but shipments continued to increase, report says[permanent dead link] UNCTAD website, published: 30 July 2010, accessed: 7 November 2010

- ^ "Hope Downs Iron Ore Project". Hancock Prospecting. Archived from the original on 21 November 2010. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ Pilbara Archived 2013-10-21 at the Wayback Machine Rio Tinto Iron Ore website, accessed: 6 November 2010

- ^ Hope Downs is still a one-mine track The Age, published: 13 April 2005, accessed: 7 November 2010

- ^ The Australian Mines Handbook - 2003-04 edition, editor: Ross Louthean, publisher: Louthean Media Pty Ltd, page: 240

- ^ Hope Downs JV Archived 2011-02-02 at the Wayback Machine Hancock Prospecting website, accessed: 7 November 2010

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hope Downs mine Archived 2010-05-14 at the Wayback Machine Rio Tinto Iron Ore website, accessed: 6 November 2010

- ^ Jump up to: a b Western Australian Mineral and Petroleum Statistic Digest 2008-09 Department of Mines and Petroleum website, accessed: 8 November 2010

- ^ Rail Archived 2013-07-01 at the Wayback Machine Rio Tinto Iron Ore website, accessed: 6 November 2010

- ^ Hope Downs deal sees wheel turn full circle The Age, published: 5 July 2005, accessed: 7 November 2010

- ^ Rio Tinto to invest $1.78b in Hope Downs The Sydney Morning Herald, published: 30 August 2010, accessed: 7 November 2010

- ^ Rio Tinto proceeds with Hope Downs iron project ABC Rural, published: 31 August 2010, accessed: 7 November 2010

- ^ "Hope Downs CD". Rolling Blackouts Coastal Fever website. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

External links[]

- Iron ore mines in Western Australia

- Surface mines in Australia

- Rio Tinto Iron Ore

- Hamersley Range