Impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson

| Impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson | |

|---|---|

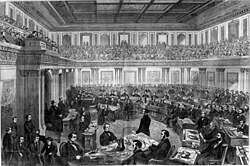

Theodore R. Davis's illustration of President Johnson's impeachment trial in the Senate, published in Harper's Weekly | |

| Accused | Andrew Johnson, President of the United States |

| Date | March 23, 1868– May 26, 1868 (2 months and 3 days) |

| Outcome | Acquitted by the U.S. Senate, remained in office |

| Charges | Eleven high crimes and misdemeanors |

| Cause | Violating the Tenure of Office Act by attempting to replace Edwin M. Stanton, the Secretary of War, while Congress was not in session and other abuses of presidential power |

| ||

|---|---|---|

15th Governor of Tennessee

16th Vice President of the United States

17th President of the United States

Vice presidential and Presidential campaigns

Post-presidency

|

||

The impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson, the 17th president of the United States, began in the U.S. Senate on March 23, 1868, and concluded with his acquittal on May 26. Johnson had been impeached by the United States House of Representatives on February 24, 1868, and eleven articles of impeachment were adopted. This was the first impeachment trial of a U.S. president.

The trial resulted in an acquittal. The Senate voted identically on three of the eleven articles of impeachment, failing each time by a single vote to reach the supermajority needed to convict Johnson. The Senate then adjourned the trial without voting on the remaining eight articles of impeachment.

Background[]

President Andrew Johnson held open disagreements with Congress, who tried to remove him several times. The Tenure of Office Act was enacted over Johnson's veto to curb his power.[1]

On January 22, 1868, the House approved by a vote of 103–37 a resolution launching an inquiry run by Committee on Reconstruction. On February 21, 1868, Johnson, in violation of the Tenure of Office Act that had been passed by Congress in March 1867 over Johnson's veto, attempted to remove Edwin Stanton, the secretary of war who the act was largely designed to protect, from office.[2] On February 22, the committee released a report which recommended Johnson be impeached for high crimes and misdemeanors.[3]

Also on January 22, 1868, a one sentence resolution to impeach Johnson, written by John Covode, was also referred to the Committee on Reconstruction. The resolution read, "Resolved, that Andrew Johnson, President of the United States, be impeached of high crimes and misdemeanors."[4][5][6] On February 24, the United States House of Representatives voted 126–47 to impeach Johnson for high crimes and misdemeanors", which were detailed in 11 articles of impeachment (the 11 articles were collectively approved in a separate vote a week after impeachment was approved).[7][8][9] The primary charge against Johnson was that he had violated the Tenure of Office Act by removing Stanton from office.[7]

Officers of the trial[]

Presiding officer[]

Per the Constitution of the United States's rules on impeachment trials of incumbent presidents, chief justice of the United States Salmon P. Chase presided over the trial.[10]

The extent of Chase's authority as presiding officer to render unilateral rulings was a frequent point of contention. He initially maintained that deciding certain procedural questions on his own was his prerogative; but after the Senate challenged several of his rulings, Chase gave up on making rulings.[11]

House managers[]

Top row L-R: Butler, Stevens, Williams, Bingham; bottom row L-R: Wilson, Boutwell, Logan

The House of Representatives appointed seven members to serve as House impeachment managers, equivalent to prosecutors. These seven members were John Bingham, George S. Boutwell, Benjamin Butler, John A. Logan, Thaddeus Stevens, Thomas Williams and James F. Wilson.[12][13] The members were appointed February 25, 1868 in a 124–42 House vote.[14]

| To pass "A Resolution Appointing a Committee to Appear Before the Bar of the Senate to Impeach Andrew Johnson, President of the United States"[14] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| February 25, 1868 | Party | Total votes | ||||

| Democratic | Republican | Conservative | Conservative Republican | Independent Republican | ||

| Yea |

0 | 124 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 124 |

| Nay | 41 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 42 |

Bingham served as chairman of the House Committee of Impeachment Managers.[15][16] He had past experience serving in such a role, having previously served as the chairman of impeachment managers for the impeachment of West H. Humphreys.[16] Boutwell had originally been chosen as the chairman of impeachment managers for Johnson's impeachment trial, but, before the trial, resigned this position in favor of having Bingham serve in it.[16]

| House managers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chairman of the House Committee of Impeachment Managers John Bingham (Republican, Ohio) |

George S. Boutwell (Republican, Massachusetts) |

Benjamin Butler (Republican, Massachusetts) |

John A. Logan (Republican, Illinois) | ||||

|

|

|

| ||||

| Thaddeus Stevens (Republican, Pennsylvania) |

Thomas Williams (Republican, Pennsylvania) |

James F. Wilson (Republican, Iowa) |

|||||

|

|

|

|||||

Johnson's counsel[]

The president's defense team was made up of Benjamin Robbins Curtis, William M. Evarts, William S. Groesbeck, Thomas Amos Rogers Nelson, and Henry Stanbery.[17] Stanbery had resigned as United States attorney general on March 12, 1868 in order to serve on Johnson's defense team.[18]

| President's counsel | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benjamin Robbins Curtis (former associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States) |

William M. Evarts | William S. Groesbeck (former member of the United States House of Representatives) |

Thomas Amos Rogers Nelson (former member of the United States House of Representatives) |

Henry Stanbery (former United States attorney general) | ||

|

|

|

|

| ||

Pretrial[]

On March 4, 1868, amid tremendous public attention and press coverage, the 11 Articles of Impeachment were presented to the Senate, which reconvened the following day as a court of impeachment, with Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase presiding, and proceeded to develop a set of rules for the trial and its officers.[10] The extent of Chase's authority as presiding officer to render unilateral rulings was a frequent point of contention during the rules debate and trial. He initially maintained that deciding certain procedural questions on his own was his prerogative; but after the Senate challenged several of his rulings, he gave up making rulings.[11]

When it came time for senators to take the juror's oath, Thomas A. Hendricks questioned Benjamin Wade's impartiality and suggested that Wade abstain from voting due to a conflict of interest. As there was no constitutional provision at the time for filling an intra-term vacancy in the vice presidency (accomplished a century later by the Twenty-fifth Amendment), the office had been vacant since Johnson succeeded to the presidency. Therefore, Wade, as president pro tempore of the Senate, would, under the Presidential Succession Act then in force and effect, become president if Johnson were removed from office. Reviled by the Radical Republican majority, Hendricks withdrew his objection a day later and left the matter to Wade's own conscience, and Wade subsequently voted for conviction.[19][20] The oaths were administered to the Senators by Chief Justice Chase on March 5 and 6.[21]

Testimony and deliberations[]

The trial was conducted mostly in open session, and the Senate chamber galleries were filled to capacity throughout. Public interest was so great that the Senate issued admission passes for the first time in its history. For each day of the trial, 1,000 color coded tickets were printed, granting admittance for a single day.[10][22]

On the advice of counsel, the president did not appear at the trial.[10]

On the first day, Johnson's defense committee asked for 40 days to collect evidence and witnesses since the prosecution had had a longer amount of time to do so, but only 10 days were granted. The proceedings began on March 23. Senator Garrett Davis argued that because not all states were represented in the Senate the trial could not be held and that it should therefore be adjourned. The motion was voted down. After the charges against the president were made, Henry Stanbery asked for another 30 days to assemble evidence and summon witnesses, saying that in the 10 days previously granted there had only been enough time to prepare the president's reply. John A. Logan argued that the trial should begin immediately and that Stanbery was only trying to stall for time. The request was turned down in a vote 41 to 12. However, the Senate voted the next day to give the defense six more days to prepare evidence, which was accepted.[23]

Prosecution's presentation[]

When the trial formally commenced on March 30,[24] House manager Benjamin Butler opened for the prosecution with a three-hour speech.[25][26] The speech reviewed historical impeachment trials, dating from King John of England.[25] In this speech, he directly refuted arguments that the Tenure of Office Act was not applicable to Johnson's dismissal of Stanton.[26] In this speech, he also read excerpts of Johnson's speeches from his infamous Swing Around the Circle. These remarks were the basis of the tenth article of impeachment.[26] He also made derisive remarks against Johnson, referring to him as an "accidental Chief" and "the elect of an Assassin", in reference to the fact that Johnson was not elected president, but rather, had ascended to the presidency after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.[26]

In the days following the start of the trial, Butler spoke out against Johnson's violations of the Tenure of Office Act and further charged that the president had issued orders directly to Army officers without sending them through General Grant. The prosecution called several witnesses in the course of the proceedings until April 9, when they rested their case.[25]

The disrespectful character of remarks Butler would make about Johnson during the trial may have hurt the prosecution's case with senators who were on the fence. Additionally, Butler is argued to have made a number of strategic errors in his presentation.[26] After their presentation, Butler and his fellow House managers publicly expressed confidence that their presentation was successful. On May 4, Butler spoke before a Republican crowd, and declared, "the removal of the great obstruction is certain." However, privately, they were less optimistic about it.[26]

A key argument made by the prosecution was an assertion that Johnson had explicitly violated the Tenure of Office Act in dismissing Stanton without the Senate's consent.[24] Another key argument made the prosecution was an assertion that the president had a duty to faithfully execute laws passed by Congress, regardless of whether the President believes the laws to be Constitutional. They argued this was the case because, if a President was not obliged to do so, they could routinely go against the will of Congress (which they argued, in turn, represented the will of the American people, as their elected representatives).[24]

While the central focus of the trial was related to Johnson's alleged violation of the Tenure of Office Act, other issues were brought up as well.[24] For instance, House managers characterized Johnson as representing a return of "slave power" to the country.[24]

Defense's presentation[]

One of the key points argued by the defense was that the language in the Tenure of Office Act was not clear, leaving vagueness as to whether the legislation itself was even applicable to the situation involving Stanton. The defense argued that Johnson had not violated the Tenure of Office Act because President Lincoln did not reappoint Stanton as Secretary of War at the beginning of his second term in 1865 and that he was, therefore, a leftover appointment from the 1860 cabinet, which, they argued, removed his protection by the Tenure of Office Act.[24] [25] Another key point argued by the defense was an assertion that the Tenure of Office Act was unconstitutional, since, they argued, it interfered with the President's constitutional authority to "take care that the laws be faithfully executed." They argued that a President could not carry out laws when they could not trust their own Cabinet advisors.[24] A third key point argued by the defense was an assertion that presidents should not be removed from office for political misdeeds through impeachment, but, rather, through elections. The defense argued that the Republican Party was abusing impeachment as a political tool.[24]

Defense counsel Benjamin Curtis called attention to the fact that after the House passed the Tenure of Office Act, the Senate had amended it, meaning that it had to return it to a Senate-House conference committee to resolve the differences. He followed up by quoting the minutes of those meetings, which revealed that while the House members made no notes about the fact, their sole purpose was to keep Stanton in office, and the Senate had disagreed. The defense then called their first witness, Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas. He did not provide adequate information in the defense's cause and Butler made attempts to use his information to the prosecution's advantage. The next witness was General William T. Sherman, who testified that President Johnson had offered to appoint Sherman to succeed Stanton as secretary of war in order to ensure that the department was effectively administered. This testimony damaged the prosecution, which expected Sherman to testify that Johnson offered to appoint Sherman for the purpose of obstructing the operation or overthrow, of the government. Sherman essentially affirmed that Johnson only wanted him to manage the department and not to execute directions to the military that would be contrary to the will of Congress.[27]

As a witness for the defense, Gideon Welles testified that Johnson's Cabinet had advised the president that the Tenure of Office Act was unconstitutional, and both Secretaries William Seward and Edwin Stanton had agreed to create a draft of a veto message. Curtis argued that this was relevant since one of the articles of impeachment charged Jonhson with "intending" to violate the Constitution, and Welles testimony portrayed Johnson as having believed that the Tenure of Office Act was unconstitutional. Originally, over the objections of the House Managers, Chief Justice Chase ruled that this testimony was admissible evidence. However, the Senate itself voted to overrule Chase's ruling by a vote of 29–20, thereby deeming it inadmissible as evidence.[28]

Thomas and Welles are considered to have been the only two noteworthy witness testimonies called by the defense.[28]

During the trial, Chief Justice Chase ruled that that Johnson should be permitted to present evidence that Thomas' appointment to replace Stanton was intended to provide a test case to challenge the constitutionality of the Tenure of Office Act, but the Senate reversed the ruling.[29]

Final arguments[]

Final arguments took place from April 22 through May 6. The House managers spoke for six days, while the president's counsel spoke for five.[28]

Prosecution's final arguments[]

The prosecution's closing arguments included hyperbolic speech.[28] Thaddeus Stevens painted Johnson as a, "wretched man, standing at bay, surrounded by a cordon of living men, each with the axe of an executioner uplifted for his just punishment". John Bingham's remarks brought immense applause from the crowd in the Senate gallery, he painted there to be a fundamental need for the, "legislative power of the people to triumph over the usurpations of an apostate President," warning that a failure for this to occur (if the Senate acquitted the president), future historians would regard the impeachment proceedings to have been the moment that, "the fabric of American empire fell and perished from the Earth."[28]

Defense's final arguments[]

In his remarks, Groesbeck offered a lively defense of Johnson's perspective of Reconstruction.[28] William Everts argued in his closing argument that violating the Tenure of Office Act did not meet the level of being an impeachable offense.[28]

Closed-door deliberations[]

On May 11, from eleven in the morning until midnight, senators held closed-door debates on the case.[26]

Verdict[]

The Senate was composed of 54 members representing 27 states (10 former Confederate states had not yet been readmitted to representation in the Senate) at the time of the trial. At its conclusion, senators voted on three of the articles of impeachment. On each occasion the vote was 35–19, with 35 senators voting guilty and 19 not guilty. As the constitutional threshold for a conviction in an impeachment trial is a two-thirds majority guilty vote, 36 votes in this instance, Johnson was not convicted. He remained in office through the end of his term on March 4, 1869, though as a lame duck without influence on public policy.[30]

Seven Republican senators were concerned that the proceedings had been manipulated to give a one-sided presentation of the evidence. Senators William P. Fessenden, Joseph S. Fowler, James W. Grimes, John B. Henderson, Lyman Trumbull, Peter G. Van Winkle,[31] and Edmund G. Ross, who provided the decisive vote,[32] defied their party by voting against conviction. In addition to the aforementioned seven, three more Republicans James Dixon, James Rood Doolittle, Daniel Sheldon Norton, and all nine Democratic senators voted not guilty.

Vote on eleventh article (May 16)[]

On May 16, the Senate convened to vote on its verdict. A motion was made, and successfully adopted, to vote first on the eleventh article of impeachment. The eleventh article was widely viewed as being the article most likely to result in a vote to convict.[26]

Prior to the vote, Samuel Pomeroy, the senior senator from Kansas, told the junior Kansas Senator Ross that if Ross voted for acquittal that Ross would become the subject of an investigation for bribery.[33] Ross was seen as a critical vote, and had been silent about his stance on impeachment throughout the trial and deliberations.[26]

Ten day hiatus[]

After the vote on the eleventh article resulted in acquittal, in hopes of persuading at least one senator who voted "not guilty" to vote "guilty" on the remaining articles, the Senate adjourned for 10 days before continuing voting on the other articles. During the hiatus, under Butler's leadership, the House put through a resolution to investigate alleged "improper or corrupt means used to influence the determination of the Senate". Despite the Radical Republican leadership's heavy-handed efforts to change the outcome, when votes were cast on May 26 for the second and third articles, the results were the same as the first. After the trial, Butler conducted hearings on the widespread reports that Republican senators had been bribed to vote for Johnson's acquittal. In Butler's hearings, and in subsequent inquiries, there was increasing evidence that some acquittal votes were acquired by promises of patronage jobs and cash bribes. Political deals were struck as well. Grimes received assurances that acquittal would not be followed by presidential reprisals; Johnson agreed to enforce the Reconstruction Acts, and to appoint General John Schofield to succeed Stanton. Nonetheless, the investigations never resulted in charges, much less convictions, against anyone.[34]

Moreover, there is evidence that the prosecution attempted to bribe the senators voting for acquittal to switch their votes to conviction. Maine Senator Fessenden was offered the ministership to Great Britain. Prosecutor Butler said, "Tell [Kansas Senator Ross] that if he wants money there is a bushel of it here to be had."[35] Butler's investigation also boomeranged when it was discovered that Kansas Senator Pomeroy, who voted for conviction, had written a letter to Johnson's postmaster general seeking a $40,000 bribe for Pomeroy's acquittal vote along with three or four others in his caucus.[36] Butler was himself told by Wade that Wade would appoint Butler as secretary of state when Wade assumed the presidency after a Johnson conviction.[37]

Votes on second and third articles and adjournment (May 26)[]

On May 26, the Senate reconvened the trial, and voted on the second and third articles, again failing to convict Johnson by the same margin as their votes for the eleventh article. After this, they voted to adjourn the trial.[38]

Summary of votes[]

| Articles of Impeachment, U.S. Senate judgment (36 "guilty" votes necessary for a conviction) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 16, 1868 Article XI |

Party | Total votes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Democratic | Republican | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yea (guilty) | 0 | 35 | 35 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nay (not guilty) |

9 | 10 | 19 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| May 26, 1868 Article II |

Party | Total votes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Democratic | Republican | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yea (guilty) | 0 | 35 | 35 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nay (not guilty) |

9 | 10 | 19 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| May 26, 1868 Article III |

Party | Total votes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Democratic | Republican | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yea (guilty) | 0 | 35 | 35 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nay (Not guilty) |

9 | 10 | 19 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Aftermath[]

Not one of the Republican senators who voted for acquittal ever again served in an elected office.[41] Although they were under intense pressure to change their votes to conviction during the trial, afterward public opinion rapidly shifted around to their viewpoint. Some senators who voted for conviction, such as John Sherman and even Charles Sumner, later changed their minds.[42][43][44]

Later review of Johnson's impeachment[]

In 1887, the Tenure of Office Act was repealed by Congress, and subsequent rulings by the United States Supreme Court seemed to support Johnson's position that he was entitled to fire Stanton without congressional approval. The Supreme Court's ruling on a similar piece of later legislation in Myers v. United States (1926) affirmed the ability of the president to remove a postmaster without congressional approval, and stated in its majority opinion "that the Tenure of Office Act of 1867...was invalid".[45]

Lyman Trumbull of Illinois, one of the 10 Republican senators whose refusal to vote for conviction prevented Johnson's removal from office, noted, in the speech he gave explaining his vote for acquittal, that had Johnson been convicted, the main source of the president's political power—the freedom to disagree with the Congress without consequences—would have been destroyed, and the Constitution's system of checks and balances along with it:[46]

Once set the example of impeaching a President for what, when the excitement of the hour shall have subsided, will be regarded as insufficient causes, as several of those now alleged against the President were decided to be by the House of Representatives only a few months since, and no future President will be safe who happens to differ with a majority of the House and two thirds of the Senate on any measure deemed by them important, particularly if of a political character. Blinded by partisan zeal, with such an example before them, they will not scruple to remove out of the way any obstacle to the accomplishment of their purposes, and what then becomes of the checks and balances of the Constitution, so carefully devised and so vital to its perpetuity? They are all gone.

An opinion that Senator Ross was mercilessly persecuted for his courageous vote to sustain the independence of the presidency as a branch of the federal government is the subject of an entire chapter in John F. Kennedy's book, Profiles in Courage.[47] That opinion has been rejected by some scholars, such as Ralph Roske, and endorsed by others, such as Avery Craven.[42][48]

References[]

- ^ "Impeachment: Andrew Johnson". The History Place. Archived from the original on November 9, 2019. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- ^ Trefousse, Hans L. (1989). Andrew Johnson: A Biography. New York City: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 306. ISBN 978-0-393-31742-8.

- ^ Hinds, Asher C. (March 4, 1907). "HINDS' PRECEDENTS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF THE UNITED STATES INCLUDING REFERENCES TO PROVISIONS OF THE CONSTITUTION, THE LAWS, AND DECISIONS OF THE UNITED STATES SENATE" (PDF). United States Congress. pp. 845–846. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ^ "Avalon Project : History of the Impeachment of Andrew Johnson - Chapter VI. Impeachment Agreed To By The House". avalon.law.yale.edu. The Avalon Project (Yale Law School Lilian Goldman Law Library). Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ "The House Impeaches Andrew Johnson | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ "Impeachment of Andrew Johnson | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- ^ a b "Johnson Impeached, February to March 1868 | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ^

This article incorporates public domain material from the Congressional Research Service document: Stephen W. Stathis and David C. Huckabee. "Congressional Resolutions on Presidential Impeachment: A Historical Overview" (PDF). Retrieved December 31, 2019.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Congressional Research Service document: Stephen W. Stathis and David C. Huckabee. "Congressional Resolutions on Presidential Impeachment: A Historical Overview" (PDF). Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^

This article incorporates public domain material from the Congressional Research Service document: Stephen W. Stathis and David C. Huckabee. "Congressional Resolutions on Presidential Impeachment: A Historical Overview" (PDF). Retrieved December 31, 2019.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Congressional Research Service document: Stephen W. Stathis and David C. Huckabee. "Congressional Resolutions on Presidential Impeachment: A Historical Overview" (PDF). Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ a b c d "The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson (1868) President of the United States". Washington, D.C.: Historical Office, United States Senate. Archived from the original on October 4, 2019. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ a b Gerhardt, Michael J. "Essays on Article I: Trial of Impeachment". Heritage Guide to the Constitution. Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on August 22, 2020. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ "List of Individuals Impeached by the House of Representatives". Washington, D.C.: Office of the Historian and the Clerk of the House's Office of Art and Archives. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ "President Andrew Johnson Impeachment Trial: 1868 - Senate Tries President Johnson". law.jrank.org. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ^ a b "TO PASS A RESOLUTION APPOINTING A COMMITTEE TO APPEAR BEFORE … -- House Vote #233 -- Feb 25, 1868". GovTrack.us. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ "The House Committee of Impeachment Managers in the Senate Chamber, Washington, D.C. | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c "THE IMPEACHMENT MANAGERS". www.impeach-andrewjohnson.com. Harper's Weekly. March 21, 1868. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ "History of the Impeachment of Andrew Johnson - Chapter VIII. Organization Of The Court Argument Of Counsel". avalon.law.yale.edu. Yale (Avalon Project).

- ^ Zuczek, Richard, ed. (2006). Encyclopedia of the Reconstruction Era. Vol. 2. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. pp. 599–600. ISBN 978-0-3133-3075-9 – via Google Books.

- ^ Hearn, Chester G. (2000). The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-0863-4.

- ^ Foner, Eric (1988). Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877. HarperCollins. p. 336. ISBN 978-0062035868.

- ^ Stathis, Stephen W.; Huckabee, David C. (September 16, 1998). "Congressional Resolutions on Presidential Impeachment: A Historical Overview" (PDF). sgp.fas.org. Congressional Research Service. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- ^ "President Andrew Johnson's impeachment trial, 1868". Washington, D.C.: Historical Office, United States Senate. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- ^ Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives; Ninety-third Congress, Second Session (1974). Impeachment: Selected Materials on Procedure. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 104–05. OCLC 868888.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Andrew Johnson's Impeachment". Bill of Rights Institute. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Stewart, David O. (2009). Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy. Simon and Schuster. pp. 207–12. ISBN 978-1416547495.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "The Impeachment Trial of Andrew Johnson: An Account". www.famous-trials.com. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- ^ Stewart, David O. (2009). Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy. Simon and Schuster. p. 231.

- ^ a b c d e f g "An Introduction to the Impeachment Trial of Andrew Johnson". law2.umkc.edu. University of Missouri - Kansas City Law School. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- ^ Herrick, Neal Q. (2009). After Patrick Henry: A Second American Revolution. New York City: Black Rose Books. p. 207. ISBN 978-1-55164-320-5.

- ^ Varon, Elizabeth R. (October 4, 2016). "Andrew Johnson: Domestic Affairs". Charlottesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved April 14, 2018.

- ^ "Andrew Johnson Trial: The Consciences of Seven Republicans Save Johnson" Archived 2018-08-10 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ ""The Trial of Andrew Johnson, 1868"". Archived from the original on August 10, 2018. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- ^ Curt Anders "Powerlust: Radicalism in the Civil War Era" p. 531

- ^ Stewart, David O. (2009). Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy. Simon and Schuster. pp. 240–49, 284–99.

- ^ Gene Davis High Crimes and Misdemeanors (New York: William Morrow & Company, 1977), 266–67, 290–91

- ^ Curt Anders "Powerlust: Radicalism in the Civil War Era", pp. 532–33

- ^ Eric McKitrick Andrew Johnson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), 507–08

- ^ "The Impeachment of President Andrew Johnson | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- ^ Ross, Edmund G. (1896). History of the Impeachment of Andrew Johnson, President of The United States By The House Of Representatives and His Trial by The Senate for High Crimes and Misdemeanors in Office 1868 (PDF). pp. 105–07. Retrieved April 26, 2018 – via Project Gutenberg, 2000.

- ^ "Senate Journal. 40th Cong., 2nd sess., 16 / 26 May 1868, 943–51". A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. Retrieved June 7, 2019.

- ^ Hodding Carter, The Angry Scar (New York: Doubleday, 1959), 143

- ^ a b Avery Craven "Reconstruction" (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1969), 221

- ^ Kenneth Stampp, Reconstruction (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1965), 153

- ^ Chester Hearn, The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2000), 202

- ^ Myers v. United States Archived 2014-12-26 at the Wayback Machine, Findlaw | Cases and Codes

- ^ White, Horace. The Life of Lyman Trumble. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1913, p. 319.

- ^ John F. Kennedy "Profiles in Courage" (New York: Harper Brothers, 1961), 115–39

- ^ Roske, Ralph J. (1959). "The Seven Martyrs?". The American Historical Review. 64 (2): 323–30. doi:10.2307/1845447. JSTOR 1845447.

- Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

- 40th United States Congress

- 1868 in American politics

- 19th-century American trials

- Trials of political people