Kaffir lime

| Kaffir lime | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fruit on tree | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Sapindales |

| Family: | Rutaceae |

| Genus: | Citrus |

| Species: | C. hystrix

|

| Binomial name | |

| Citrus hystrix DC.[1]

| |

| |

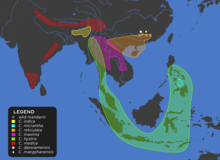

| Map of inferred original wild ranges of the main Citrus cultivars, with C. hystrix in pale green[2] | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

Citrus hystrix, called the kaffir lime, makrut lime[4] (US: /ˈmækrət/, UK: /məkˈruːt/), Thai lime or Mauritius papeda,[5] is a citrus fruit native to tropical Southeast Asia and southern China.[6][7]

Its fruit and leaves are used in Southeast Asian cuisine and its essential oil is used in perfumery.[8] Its rind and crushed leaves emit an intense citrus fragrance.

Names[]

"Kaffir" is thought to ultimately derive from the Arabic kafir, meaning infidel, though the mechanism by which it came to be applied to the lime is uncertain. Following the takeover of the Swahili coast, Muslims used the term to refer to the non-Muslim indigenous Africans, who were increasingly abducted for the Indian Ocean slave trade, which reached a height in the fifteenth and sixteenth century.[citation needed]

The most likely etymology is through the Kaffirs, an ethnic group in Sri Lanka partly descended from Bantu slaves.[9] The earliest known reference, under the alternative spelling "caffre" is in 1888 book The Cultivated Oranges, Lemons Etc. of India and Ceylon by Emanuel Bonavia, who notes, "The plantation coolies also smear it over their feet and legs, to keep off land leeches; and therefore in Ceylon [Sri Lanka] it has got also the name of Kudalu dchi, or Leech Lime. Europeans call it Caffre Lime."[9][10] Similarly, H.F. MacMillan's 1910 book A Handbook of Tropical Gardening and Planting notes, "The 'Kaffir Lime' in Ceylon."[9][11]

Another proposed etymology is directly by Indian Muslims of the imported fruit from the non-Muslim lands to the east to "convey otherness and exotic provenance."[9] Claims that the name of the fruit derives directly from the South African ethnic slur "kaffir" (see "Name" below) are not well supported.[9]

C. hystrix is known by various names in its native areas:

- jeruk purut in Indonesian and limau purut in Malay. Purut, "rough-skinned", refers to the bumpy texture of the fruit.[12]

- jiàn yè chéng (箭叶橙) in Chinese.

- kabuyaw or kulubot in the Philippines.[13] The city of Cabuyao in Laguna is named after the fruit.[14]

- makrud or makrut (มะกรูด, /máʔ.krùːt/) in Thailand (a name also used for the bergamot orange).

- mak khi hut (ໝາກຂີ້ຫູດ, /ma᷆ːk.kʰi᷆ː.hu᷆ːt/) in Laos.

- trúc or chanh sác in Vietnam.[6][15]

- combava in Réunion Island

The micrantha, a similar citrus fruit native to the Philippines that is ancestral to several hybrid limes, such as the Key lime and Persian lime, may represent the same species as C. hystrix, but genomic characterization of the kaffir lime has not been performed in sufficient detail to allow a definitive conclusion.[16]

Name[]

In South Africa, the Arabic kafir was adopted by White colonialists as "kaffir,"[9] an ethnic slur for black African people.[17] Consequently, some authors favour switching from "kaffir lime" to "makrut lime", a less well-known name, while in South Africa it is usually referred to as "Thai lime".[18][19][20]

Description[]

C. hystrix is a thorny bush, 2 to 11 metres (6 to 35 ft) tall, with aromatic and distinctively shaped "double" leaves.[21][22] These hourglass-shaped leaves comprise the leaf blade plus a flattened, leaf-like stalk (or petiole). The fruit is rough and green, and ripens to yellow; it is distinguished by its bumpy exterior and its small size, approximately 4 cm (2 in) wide.[22]

History[]

Pierre Sonnerat (1748-1814) collected specimens of it in 1771-72 and it appears in Lamarck's Encyclopédie Méthodique (1796)[23][24]

Kaffir lime appears in texts under the name of kaffir lime in 1868, in Ceylon, where rubbing the juice onto legs and socks prevents leech bites[25] This could be a possible origin of the name leech lime.

Uses[]

Cuisine[]

C. hystrix leaves are used in Southeast Asian cuisines such as Indonesian, Laotian, Cambodian, and Thai.[citation needed] The leaves are the most frequently used part of the plant, fresh, dried, or frozen. The leaves are widely used in Thai[26][27] (for dishes such as tom yum) and Cambodian cuisine (for the base paste "krueng").[28] The leaves are used in Vietnamese cuisine to add fragrance to chicken dishes and to decrease the pungent odor when steaming snails. The leaves are used in Indonesian cuisine (especially Balinese cuisine and Javanese cuisine) for foods such as soto ayam and are used along with Indonesian bay leaf for chicken and fish. They are also found in Malaysian and Burmese cuisines.[29]

The rind (peel) is commonly used in Lao and Thai curry paste, adding an aromatic, astringent flavor.[26] The zest of the fruit, referred to as combava,[citation needed] is used in creole cuisine to impart flavor in infused rums and in Mauritius, Réunion, and Madagascar.[30] In Cambodia, the entire fruit is crystallized/candied for eating.[31]

Medicinal[]

The juice and rinds of the peel are used in traditional medicine in some Asian countries; the fruit's juice is often used in shampoo and is believed to kill head lice.[22]

Other uses[]

The juice finds use as a cleanser for clothing and hair in Thailand[27] and very occasionally in Cambodia. Lustral water mixed with slices of the fruit is used in religious ceremonies in Cambodia.

Kaffir lime oil is used as raw material in many fields, some of which include pharmaceutical, agronomic, food, sanitary, cosmetic, and perfume industries. It is also used extensively in aromatherapy and as an essential ingredient of various cosmetic and beauty products.[32]

C. hystrix leaves floating in tom yum

Fruit cross-section

Dried fruit rinds

Powdered fruit rind, used in Malagasy cuisine

Cut leaf strips on chicken phanaeng

Cultivation[]

C. hystrix is grown worldwide in suitable climates as a garden shrub for home fruit production. It is well suited to container gardens and for large garden pots on patios, terraces, and in conservatories.

Main constituents[]

The compound responsible for the characteristic aroma was identified as (–)-(S)-citronellal, which is contained in the leaf oil up to 80 percent; minor components include citronellol (10 percent), nerol and limonene.

From a stereochemical point of view, it is remarkable that kaffir lime leaves contain only the (S) stereoisomer of citronellal, whereas its enantiomer, (+)-(R)-citronellal, is found in both lemon balm and (to a lesser degree) lemon grass, (however, citronellal is only a trace component in the latter's essential oil).

Kaffir lime fruit peel contains an essential oil comparable to lime fruit peel oil; its main components are limonene and β-pinene.[8][33]

Toxicity[]

C. hystrix contains significant quantities of furanocoumarins, in both the peel and the pulp.[34] Furanocoumarins are known to cause phytophotodermatitis,[35] a potentially severe skin inflammation. One case of phytophotodermatitis induced by C. hystrix has been reported.[36]

See also[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Citrus hystrix. |

- Citrus taxonomy – Botanical classification of the genus Citrus

References[]

- ^ "TPL, treatment of Citrus hystrix DC". The Plant List; Version 1. (published on the internet). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and the Missouri Botanical Garden. 2010. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- ^ Fuller, Dorian Q.; Castillo, Cristina; Kingwell-Banham, Eleanor; Qin, Ling; Weisskopf, Alison (2017). "Charred pomelo peel, historical linguistics and other tree crops: approaches to framing the historical context of early Citrus cultivation in East, South and Southeast Asia". In Zech-Matterne, Véronique; Fiorentino, Girolamo (eds.). AGRUMED: Archaeology and history of citrus fruit in the Mediterranean. Publications du Centre Jean Bérard. pp. 29–48. doi:10.4000/books.pcjb.2107. ISBN 9782918887775.

- ^ The Plant List: A Working List of All Plant Species, retrieved 3 October 2015

- ^ D.J. Mabberley (1997), "A classification for edible Citrus (Rutaceae)", Telopea, 7 (2): 167–172, doi:10.7751/telopea19971007

- ^ "Citrus hystrix". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Citrus hystrix". Flora & Fauna Web. National Parks Singapore, Singapore Government. Retrieved 13 August 2018.[dead link]

- ^ "Citrus hystrix". Plant Finder. Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ng, D.S.H.; Rose, L.C.; Suhaimi, H.; Mohamad, H.; Rozaini, M.Z.H.; Taib, M. (2011). "Preliminary evaluation on the antibacterial activities of Citrus hystrix oil emulsions stabilized by TWEEN 80 and SPAN 80" (PDF). International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. 3 (Suppl. 2).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Anderson, L. V. (3 July 2014). "Is the Name Kaffir Lime Racist? Why You May Want to Think Twice About Using That Term". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ Macmillan, Hugh Fraser (1910). A handbook of tropical gardening and planting with special reference to Ceylon. Colombo, Ceylon: H. W. Cave & Co. p. 157.

- ^ pann (2019-04-07). "Apa itu purut?". Glosarium Online (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2020-09-02.

- ^ CRC World Dictionary of Medicinal and Poisonous Plants: Common Names, Scientific Names, Eponyms, Synonyms, and Etymology. M-Q. CRC Press/Taylor & Francis. 2012-01-01. ISBN 9781439895702.

- ^ CRC World Dictionary of Medicinal and Poisonous Plants: Common Names, Scientific Names, Eponyms, Synonyms, and Etymology. M-Q. CRC Press/Taylor & Francis. 2012-01-01. ISBN 9781439895702.

- ^ Katzer, Gernot. "Kaffir Lime (Citrus hystrix DC.)". Gernot Katzer's Spice Pages. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ Ollitrault, Patrick; Curk, Franck; Krueger, Robert (2020). "Citrus taxonomy". In Talon, Manuel; Caruso, Marco; Gmitter, Fred G, Jr. (eds.). The Citrus Genus. Elsevier. pp. 57–81. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-812163-4.00004-8. ISBN 9780128121634.

- ^ Veronica Vinje: Saying "kaffir lime" is like saying the N-word before 'Lime' - Veronica Vinje, June 23. 2014, Straight.com

- ^ McKenna, Maryn (2014-07-18), "A Food Has a Historic, Objectionable Name. Should We Change It?", National Geographic, retrieved 12 December 2015

- ^ Common lime name has racist history by Khalil Akhtar, CBC News, Jul 8, 2014

- ^ "Kaf·fir also kaf·fir". American Heritage Dictionary. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ Kumar, Kuntal (1 January 2008). The Original Organics Cookbook: recipes for healthy living. TERI Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-81-7993-155-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Staples, George; Kristiansen, Michael S. (1 January 1999). Ethnic Culinary Herbs: A Guide to Identification and Cultivation in Hawai'i. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 27–29. ISBN 978-0-8248-2094-7.

- ^ https://www.nparks.gov.sg/sbg/research/publications/gardens-bulletin-singapore/-/media/sbg/gardens-bulletin/4-4-54-2-04-y2002-v54p2-gbs-pg-185.pdf

- ^ Bonavia, Emanuel (1888–90). The cultivated oranges and lemons, etc. of India and Ceylon, with researches into their origin and the derivation of their names, and other useful information. With and atlas of illustrations. London: W. H. Allen. p. 309. Retrieved 31 May 2021.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- ^ Henderson, John (capt. 78th Highlanders.) (1868). Skeet, Ch. J. (ed.). The History of the Rebellion in Ceylon During Lord Torrington's Government: Affording a Comparison with Jamaica and Governor Eyre. University of Minnesota. p. 58. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Loha-unchit, Kasma. "Kaffir Lime –Magrood". Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sukphisit, Suthon (12 November 2017). "Clean up in kitchen with versatile fruit". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ^ "What to Replace Kaffir Lime Leaves With". Village Bakery. 2018-12-17. Retrieved 2018-12-19.

- ^ Wendy Hutton, Wendy; Cassio, Alberto (2003). Handy Pocket Guide to Asian Herbs & Spices. Singapore: Periplus Editions. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-7946-0190-4.

- ^ "Mauritian rum has a distinct character to it: Sweeter and smoother". The Economic Times. 2015-03-22.

- ^ Dy Phon Pauline, 2000, Plants Used In Cambodia, printed by Imprimerie Olympic, Phnom Penh

- ^ Suresh, Anuja; Velusamy, Sangeetha; Ayyasamy, Sudha; Rathinasamy, Menaha (2021). "Techniques for essential oil extraction from kaffir lime and its application in health care products—A review". Flavour and Fragrance Journal. 36: 5–21. doi:10.1002/ffj.3626.

- ^ Kasuan, Nurhani (2013). "Extraction of Citrus hystrix D.C. (Kaffir Lime) Essential Oil Using Automated Steam Distillation Process: Analysis of Volatile Compounds" (PDF). Malyasian Journal of Analytical Sciences. 17 (3): 359–369.

- ^ Dugrand-Judek, Audray; Olry, Alexandre; Hehn, Alain; Costantino, Gilles; Ollitrault, Patrick; Froelicher, Yann; Bourgaud, Frédéric (November 2015). "The Distribution of Coumarins and Furanocoumarins in Citrus Species Closely Matches Citrus Phylogeny and Reflects the Organization of Biosynthetic Pathways". PLOS ONE. 10 (11): e0142757. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1042757D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0142757. PMC 4641707. PMID 26558757.

- ^ McGovern, Thomas W.; Barkley, Theodore M. (2000). "Botanical Dermatology". The Electronic Textbook of Dermatology. Internet Dermatology Society. 37 (5). Section Phytophotodermatitis. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00385.x. PMID 9620476. S2CID 221810453. Retrieved November 29, 2018.

- ^ Koh, D.; Ong, C. N. (April 1999). "Phytophotodermatitis due to the application of Citrus hystrix as a folk remedy". Br J Dermatol. 140 (4): 737–738. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02782.x. PMID 10233333. S2CID 45603195.

- Asian cuisine

- Limes (fruit)

- Citrus

- Flora of China

- Flora of tropical Asia

- Fruits originating in Asia

- Garden plants of Asia

- Herbs

- Lao cuisine

- Philippine cuisine

- Spices

- Thai cuisine