Karachays

hideThis article has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Къарачайлыла | |

|---|---|

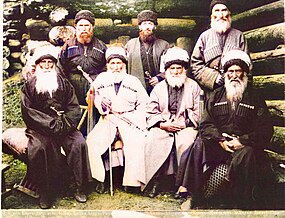

Karachay men in the 19th century | |

| Total population | |

| 245,000[citation needed] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 218,403[1] | |

| 20,000[2] | |

| 995[citation needed] | |

| Languages | |

| Karachay, Russian, Turkish (diaspora) | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Balkars, Nogais, Kumyks | |

The Karachays (Karachay-Balkar: Къарачайлыла, romanized: Qaraçaylıla or таулула, romanized: tawlula, lit. 'Mountaineers')[3] are a Turkic people of the North Caucasus, mostly situated in the Russian Karachay–Cherkess Republic.

History[]

The Karachays are a Turkic people descended from the Kipchaks, and share their language with the Kumyks from Daghestan.

The Kipchaks (Cumans) came to the Caucasus in the 11th century CE. The state of Alania was established prior to the Mongol invasions and had its capital in Maghas, which some authors locate in Arkhyz, the mountains currently inhabited by the Karachay, while others place it in either what is now modern Ingushetia or North Ossetia. In the 14th century, Alania was destroyed by Timur and the decimated population dispersed into the mountains. Timur's incursion into the North Caucasus introduced the local nations to Islam.

In the nineteenth century Russia took over the area during the Russian conquest of the Caucasus. On October 20, 1828 the took place, in which the Russian troops were under the command of General Georgy Emanuel. The day after the battle, as Russian troops were approaching the aul of , the Karachay elders met with the Russian leaders and an agreement was reached for the inclusion of the Karachay into the Russian Empire.

After the annexation, the self-government of Karachay was left intact, including its officials and courts. Interactions with neighboring Muslim peoples continued to take place based on both folk customs and Sharia law. In Karachay, soldiers were taken from Karachai Amanat, pledged an oath of loyalty, and were assigned arms.

From 1831 to 1860, the Karachays were divided. A large portion of Karachays joined the anti-Russian struggles carried out by the North Caucasian peoples; while another significant portion of Karachays, due to being encouraged by the Volga Tatars and Bashkirs, another fellow Turkic Muslim peoples that have long loyal to Russia, voluntarily cooperated with Russian authorities in the Caucasian War. Between 1861 and 1880, to escape reprisals by the Russian army, some of the Karachays migrated to Turkey although the main part of Karachays still remain in modern territory.

All Karachay officials were purged by early 1938, and the entire nation was administered by NKVD officers, none of whom were Karachay. In addition, the entire intelligentsia , all rural officials and at least 8,000 ordinary farmers were arrested, including 875 women. Most were executed, but many were sent to prison camps throughout the Caucasus.[4]

Deportation[]

In 1942 the Germans permitted the establishment of a to administer their "autonomous region"; the Karachays were also allowed to form their own police force and establish a brigade that was to fight with the Wehrmacht.[5] This relationship with Nazi Germany resulted, when the Russians regained control of the region in November 1943, with the Karachays being charged with collaboration with Nazi Germany and deported.[6] Originally restricted only to family members of rebel bandits during World War II, the deportation was later expanded to include the entire Karachay ethnic group. The Soviet government refused to acknowledge that 20,000 Karachays served in the Red Army, greatly outnumbering the 3,000 estimated to have collaborated with the German soldiers.[7] Karachays were forcibly deported and resettled in Central Asia, mostly in Kazakhstan and Kirghizia.[8] In the first two years of the deportations, disease and famine caused the death of 35% of the population; of 28,000 children, 78%, or almost 22,000 perished.[9]

Diaspora[]

Many Karachays migrated to Turkey after the Russian annexation of the Karachay nation in the early 19th century. Karachays were also forcibly displaced to the Central Asian republics of Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Kirghizia during Joseph Stalin's relocation campaign in 1944. Since the Nikita Khrushchev era in the Soviet Union, the majority of Karachays have been repatriated to their homeland from Central Asia. Today, there are sizable Karachay communities in Turkey (centered on Afyonkarahisar), Uzbekistan, the United States, and Germany.

Geography[]

The Karachay nation, along with the Balkars occupy the valleys and foothills of the Central Caucasus in the river valleys of the Kuban, , Malka, Baksan, Cherek and others.

The Karachays are very proud of the symbol of their nation, Mount Elbrus, the highest mountain in Europe, with an altitude of 5,642 meters.

Culture[]

Like other peoples in the mountainous Caucasus, the relative isolation of the Karachay allowed them to develop their particular cultural practices, despite general accommodation with surrounding groups.[10]

Karachay people live in communities that are divided into families and clans (tukums). A tukum is based on a family's lineage and there are roughly thirty-two Karachay tukums. Prominent tukums include: Aci, Batcha (Batca), Baychora, Bayrimuk (Bayramuk), Bostan, Catto (Jatto), Cosar (Çese), Duda, Hubey (Hubi), Karabash, Laypan, Lepshoq, Ozden (Uzden), Silpagar, Tebu, Teke, Toturkul, Urus.[citation needed]

Karachay people are very independent, and have strong traditions and customs which dominate many aspects of their lives: e.g. weddings, funerals, and family pronouncements.

Language[]

The Karachay dialect of the Karachay-Balkar language comes from the northwestern branch of Turkic languages. The Kumyks, who live in northeast Dagestan, speak a closely related language, the Kumyk language.

Religion[]

The majority of the Karachay people are followers of Islam.[11] Some Karachays began adopting Islam in the 17th due to contact with the Nogais and Crimean Tatars.[12] Most Karachays adopted Islam by the mid-eighteenth century via the influence of the Kabardians. The Karachays are considered deeply religious. The Sufi Qadiriya order has a presence in the region.[13]

See also[]

- Karachay horse

- Balkars

- Cumans

References[]

- ^ "ВПН-2010". Perepis-2010.ru. Retrieved 2015-03-16.

- ^ – Malkar Türkleri Archived October 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Peter B. Golden (2010). Turks and Khazars: Origins, Institutions, and Interactions in Pre-Mongol Eurasia. p. 33.

- ^ Comins-Richmond, Walter (September 2002). "The deportation of the Karachays". Journal of Genocide Research. 4 (3): 431–439. doi:10.1080/14623520220151998. ISSN 1462-3528. S2CID 71183042.

- ^ Norman Rich: Hitler's War Aims. The Establishment of the New Order, page 391.

- ^ In general, see Pohl, J. Otto (1999). Ethnic Cleansing in the USSR, 1937-1949. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-30921-2.

- ^ Comins-Richmond, Walter (September 2002). "The deportation of the Karachays". Journal of Genocide Research. 4 (3): 431–439. doi:10.1080/14623520220151998. ISSN 1462-3528. S2CID 71183042.

- ^ Pohl lists 69,267 as being deported (Pohl 1999, p. 77); while Tishkov says 68,327 citing Bugai, Nikoli F. (1994) Repressirovannie narody Rossii: Chechentsy i Ingushy citing Beria, (Tishkov, Valery (2004). Chechnya: Life in a War-Torn Society. University of California Press. p. 25.); and Kreindler says 73,737 (Kreindler, Isabelle (1986). "The Soviet Deported Nationalities: A summary and an update". Soviet Studies. 38 (3): 387–405. doi:10.1080/09668138608411648.).

- ^ Grannes, Alf (1991). "The Soviet deportation in 1943 of the Karachays: a Turkic Muslim people of North Caucasus". Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs. 12 (1): 55–68. doi:10.1080/02666959108716187.

- ^ Richmond, Walter (2008). The Northwest Caucasus: Past, Present, Future. Central Asian studies series, 12. London: Routledge. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-415-77615-8.

- ^ Cole, Jeffrey E. (2011-05-25). Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 219–220. ISBN 978-1-59884-303-3.

- ^ Akiner, Shirin (1986). Islamic Peoples Of The Soviet Union. Routledge. p. 202. ISBN 978-1-136-14266-6.

- ^ Bennigsen, Alexandre; Wimbush, S. Enders (1986). Muslims of the Soviet Empire: A Guide. Indiana University Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-253-33958-4.

- Pohl, J. Otto (1999), Ethnic Cleansing in the USSR, 1937-1949, Greenwood, ISBN 0-313-30921-3

External links[]

- Turkic peoples of Europe

- Ethnic groups in Russia

- Ethnic groups in Turkey

- Ethnic groups in Kazakhstan

- Karachay-Cherkessia

- Peoples of the Caucasus

- Muslim communities of Russia