Kurdish women

| Part of a series on |

| Women in society |

|---|

|

Kurdish women (Kurdish: ژنانی کورد or Jinên Kurd) have traditionally played important roles in Kurdish society and politics.[1] In general, Kurdish women's rights and equality have improved dramatically in the 21st century due to progressive movements within Kurdish society.[2] However, despite the progress, Kurdish and international women's rights organizations still report problems related to gender inequality, forced marriages, honor killings, and in Iraqi Kurdistan, female genital mutilation (FGM).[3][4][5][6][7]

Historical accounts[]

In politics[]

Knowledge about the early history of Kurdish women is limited by both the dearth of records and the near absence of research. In 1597 (16th century), Prince Sharaf ad-Din Bitlisi wrote a book titled Sharafnama, which makes references to the women of the ruling landowning class, and their exclusion from public life and the exercise of state power. It says that the Kurds of the Ottoman Empire, who follow Islamic tradition, took four wives and, if they could afford it, four maids or slave girls. This regime of polygyny was, however, practiced by a minority, which included primarily the members of the ruling landowning class, the nobility, and the religious establishment. Sharaf ad-Din Bitlisi also mentioned three Kurdish women assuming power in Kurdish principalities after the death of their husbands in order to transfer it to their sons upon their adulthood.[8] While generally referring to women using degrading words, Bitlisi extols the ability of the three women to rule in the manner of males, and calls one of them a "lioness".[9] In the court of the powerful Bidlis principality (region in Turkey), Kurdish women were not allowed into the marketplace, and would be killed if they went there, but women did occasionally assume power in Kurdish principalities after some Ottoman authorities had made some exceptions by accepting the succession in those principalities by a female ruler.[10]

In the late 19th century, Lady Halima Khanim of Hakkari was the ruler of Bash Kala until she was forced to surrender to the Ottoman government after the suppression of the Bedir Khan revolt in 1847. A young Kurdish woman named Fatma became chief of the Ezdinan tribe in 1909 and she was known among her tribe as the queen. During World War I, Russian forces negotiated safe passage through tribal territory with Lady Maryam of the famous Nehri family, who according to Basile Nikitine, wielded great authority among her followers. Lady Adela, ruler of Halabja, exerted great influence in the affairs of the Jaff tribe in the Shahrazur plain on the Turco-Iranian frontier. The revival of commerce and restoration of law and order in the region of Halabja is attributed to her sound judgement.[11]

Lady Adela, called the "Princess of the Brave" by the British, was a famous and cultured chief of the Jaff tribe, one of the biggest Kurdish tribes, if not the biggest, native to the Zagros area, which is divided between Iran and Iraq. Adela Khanem was of the famous aristocratic Sahibqeran family, who intermarried with the tribal chiefs of Jaff.[12]

In 1993, Martin Van Bruinessen argued that Kurdish society was known as a male-dominated society, but with instances of Kurdish women becoming important political leaders.[13]

In society and literature[]

Asenath Barzani, who is considered the first female rabbi in Jewish history by some scholars, is believed to be the first known influential Kurdish woman in history. She wrote many letters and published several publications in the 17th century. In 1858, the Kurdish writer Mahmud Bayazidi mentioned the life of Kurdish women in tribal, nomadic and rural communities. He noted that the majority of marriages were monogamous and Kurdish did not veil and they participated in social activities such as work, dancing and singing together with men. When the tribe was attacked, women took part in war alongside men.[15] In traditional Kurdish literature, both matriarchal and patriarchal tendencies are found. In the Ballad of "Las and Khazal" (Beytî Las û Xezal), female tribal rulers openly compete over a lover, while in patriarchal contexts, women are subject to male violence.[10]

Mestureh Ardalan (1805–1848) was a Kurdish poet and writer. She is well known for her literary works.

Accounts of Western travellers[]

European travelers sometimes noted the absence of veil, free association with males (such as strangers and guests), and female rulers.[16] Vladimir Minorsky has reported several cases of Kurdish women running the affairs of their tribes. He met one of these female chiefs named Lady Adela in the region of Halabja in 1913. She was known for saving the lives of many British army officers during World War I and was awarded the title of Khan-Bahadur by the British commander.[17]

Kurdish women in Turkey[]

Background and history[]

In 1919, Kurdish women formed their first organization, the "Society for the Advancement of Kurdish Women", in Istanbul.[18]

During the revolts of 1925–1937, the army targeted Kurdish women, many of whom committed suicide to escape rape and abuse.[19]

The ascent to power of the Islamist conservative Justice and Development Party (AKP) in Turkey from 2002 brought with it a regressive agenda concerning women's role in society. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan infamously stated that "a woman who rejects motherhood, who refrains from being around the house, however successful her working life is, is deficient, is incomplete."[20]

Contemporary developments[]

Since its founding in 1978, the Apoist militant guerilla Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) has attracted much interest among Kurdish women, who were an integral part of the movement all along.[21] The motivation to join has been described as such: "Women join the PKK to escape poverty. They flee a conservative society where domestic violence is common and there is little opportunity for women. Other female guerillas are university graduates. They study Kurdish history and Ocalan, as well as the Marxist theories at the root of the PKK, and consider fighting as much an intellectual exercise as a physical one. Many join because of relatives in prison, and others join to avoid prison."[21] In her book "Blood and Belief" on the PKK, Aliza Marcus elaborates the reaction of Kurdish society in Turkey, deeply rooted in tradition, to the PKK's women fighters as "a mixture of shock and pride".[21]

By the mid-1990s, thousands of women had joined the ranks of PKK, and the Turkish mainstream media began a campaign of vilifying them as "prostitutes". In 1996, Kurdish women formed their own feminist associations and journals such as Roza and Jujin.[22] In 2013, The Guardian reported that 'the rape and torture of Kurdish prisoners in Turkey are disturbingly commonplace'.[23]

However, eight Kurdish women stood successfully as independent candidates in the 2007 parliamentary election, joining the Democratic Society Party after they entered the Turkish parliament.

In 2012, the pro-Kurdish, feminist Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP) was founded. In its program, it calls itself a "women’s party" and promises a women's ministry to address gendercide and institutional gender discrimination.[24] It has female and male co-chairpersons for all levels of responsible and representative office.[25] The HDP entered the 2015 parliamentary elections with feminist (as well as LGBT) candidates.[26][27] The success of the HDP in the June 2015 election was hailed as "revolutionary" in the international press, with The Guardian asserting that "until the arrival of the HDP, there has never been a party recognising that women have struggled to assert their rights throughout Turkey’s history."[24]

By December 2016, The New York Times headlined the situation in Turkish Kurdistan as "Crackdown in Turkey Threatens a Haven of Gender Equality Built by Kurds".[28] Vahap Coskun, law professor in Diyarbakir university and a critic of the PKK, concedes that the Apoist Kurdish parties’ promotion of women has had an impact all over Turkey: "It also influenced other political parties to declare more women candidates, in western Turkey too. It has also increased the visibility of women in social life as well as the influence of women in political life," with female political candidates increasing significantly even in the ruling Islamist AKP party.[28]

In the Kurdish dominated south-east, among women, the rate of illiteracy in 2000 was nearly three times that of men. Especially in the east of the country the situation is worse: in Sirnak, 66, in Hakkari 58, and in Siirt, 56 per cent of women, aged 15, could not read and write. In other provinces of the area it looked barely better.[29]

Also in southeastern Turkey, a report by the BBC estimated that almost a quarter of all marriages are polygamous. Even though it is illegal in Turkey, in practice polygamy is allowed to continue. Nick Read wrote in the BBC that in remote areas like south-east Anatolia, "Turkey risks antagonising Kurdish separatists by intervening in tradition and customs".[30] Also the New York Times noted that while banned by Atatürk, polygamy remains widespread in the "deeply religious and rural Kurdish region of southeastern Anatolia, home to one-third of Turkey's 71 million people".[31]

Renowned Kurdish women[]

- Sakine Cansız was one of the co-founders of the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) and has been called "a legend among PKK members" and "the most prominent and most important female Kurdish activist."[32]

- Leyla Zana was the first Kurdish woman elected to Parliament of Turkey in 1991. During her inauguration speech, she identified herself as a Kurd and spoke in Kurdish. She was subsequently stripped of her immunity and sentenced to 15 years in prison. She was recognized by Amnesty International as a prisoner of conscience and was awarded the Sakharov Prize by the European Union in 1995.

- Feleknas Uca is a Yazidi politician active in Germany and Turkey.

Namus-based violence issues[]

Violence against women motivated by a "Namus" based concept of honor of the family or clan have been described as endemic in Turkey, in particular in the Southeastern Anatolia Region, the predominantly Kurdish area of Turkey.[33][34][35] A July 2008 study by a team from Dicle University on honor killings in the Southeastern Anatolia Region has so far shown that little if any social stigma is attached to honor killing. The team interviewed 180 perpetrators of honor killings and it also commented that the practice is not related to a feudal societal structure, "there are also perpetrators who are well-educated university graduates. Of all those surveyed perpetrators, 60 percent are either high school or university graduates or at the very least, literate".[33][34] A survey where 500 men were interviewed in Diyarbakir found that, when asked the appropriate punishment for a woman who has committed adultery, 37% of respondents said she should be killed, while 21% said her nose or ears should be cut off.[36][37][38] However, Turkish government and media have adopted an approach to inappropriately ethnicize honor killings as purely Kurdish problems.[39]

In order to oppose the militant among Kurdish movements, the Turkish state has for decades been actively organizing and arming tribalist Kurdish forces under a "village guard system". These guards have committed rape and 78 abductions.[40] The governing Justice and Development Party (AKP) persistently pursues a conservative Islamist political agenda of enforcing regressive values of male supremacy, up to "legitimising rape and encouraging child marriage";[20] these policies have hindered the progress of Kurdish women's rights movement.[41]

While Apoist progressive Kurdish parties have achieved major successes against Namus-based violence against women,[28] as of late 2016 the Islamist AKP government of Turkey is cracking down on the progressive Kurdish movement, arresting elected female co-mayors throughout the Kurdish regions and appointing male trustees to take their place, which then dismantle the co-executives, close women's centers and outlaw the diversion of abusers’ paychecks.[28] "This crackdown is actually aiming at women and shutting down women’s organizations. It's a blow against women’s freedom. They made lots of statements like, ‘You should go and have three kids,’" says Feleknas Uca, a female Kurdish member of the Turkish Parliament.[28] Meral Danis Bestas, another female Kurdish member of Parliament, however says that "this crackdown is not powerful enough to change our principles."[28]

Turkish courts have in some cases sentenced whole families to life imprisonment for an honor killing, in 2009 where a Turkish Court sentenced five members of a Kurdish family to life imprisonment for the honor killing of 16-year old Naile Erdas, who got pregnant after she was raped.[35][42]

Kurdish women in Syria[]

Background and history[]

While Syria has developed some fairly secular features during independence in the second half of the 20th century, personal status law is still based on Sharia[43] and applied by Sharia Courts.[44]

Contemporary developments[]

With the Syrian Civil War, the Kurdish populated area in Northern Syria has gained de facto autonomy as the Federation of Northern Syria - Rojava, with the leading political actor being the progressive Democratic Union Party (PYD). Kurdish women have several armed and non-armed organizations in Rojava, and enhancing women's rights is a major focus of the political and societal agenda. Kurdish female fighters in the Women's Protection Units (YPJ) played a key role during the Siege of Kobani and in rescuing Yazidis trapped on Mount Sinjar, and their achievements have attracted international attention as a rare example of strong female achievement in a region in which women are heavily repressed.[45][46][47][48][49]

The civil laws of Syria are valid in Rojava, as far as they do not conflict with the Constitution of Rojava. One notable example for amendment is personal status law, in Syria still Sharia-based,[43][44] where Rojava introduced civil law and proclaims absolute equality of women under the law and a ban on forced marriage as well as polygamy was introduced,[50] while underage marriage was outlawed as well.[51] For the first time in Syrian history, civil marriage is being allowed and promoted, a significant move towards a secular open society and intermarriage between people of different religious backgrounds.[52]

The legal efforts to reduce cases of underage marriage, polygamy and honor killings are underpinned by comprehensive public awareness campaigns.[53] In every town and village, a women's house is established. These are community centers run by women, providing services to survivors of domestic violence, sexual assault and other forms of harm. These services include counseling, family mediation, legal support, and coordinating safe houses for women and children.[54] Classes on economic independence and social empowerment programs are also held at women's houses.[55]

All administrative organs in Rojava are required to have male and female co-chairs, and forty percent of the members of any governing body in Rojava must be female.[56] An estimated 25 percent of the Asayish police force of the Rojava cantons are women, and joining the Asayish is described in international media as a huge act of personal and societal liberation from an extremely patriarchical background, for ethnic Kurdish and ethnic Arab women alike.[57]

The PYD's political agenda of "trying to break the honor-based religious and tribal rules that confine women" is controversial in conservative quarters of society.[51]

Renowned Kurdish women[]

- Asya Abdullah is the co-chairwoman of the Democratic Union Party (PYD), the leading political party in Rojava.

- Hêvî Îbrahîm is the prime minister of Afrin Canton.

- Hediya Yousef is an ex-guerilla[58] and co-chairwoman of the executive committee of the Federation of Northern Syria – Rojava.[59]

- Îlham Ehmed is co-chairwoman of the Syrian Democratic Council.

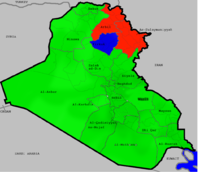

Kurdish women in Iraq[]

The neutrality of this section is disputed. (April 2016) |

Background and history[]

According to Zeynep N. Kaya, "There is a long history of women’s rights activism in both Iraq as a whole and in the Kurdistan Region, as well as long-standing momentum from below to enact change, and a willingness to realise this change among certain sections of policymakers."[60] The prominent Kurdish poet Abdullah Goran, who was born in Halabja in 1904, denounced discrimination and violence against women.[61] The first journal for Kurdish women, Dengî Afiret "Woman's Voice", was published in 1953. Following the overthrow of the monarchy in 1958, the Union of Kurdish Women lobbied for legal reform in the Iraqi civil law and succeeded in bringing marriage under civil control and abolishing honor killing. Honor killings were a serious problem among Muslim communities until Iraq outlawed them. The first female judge in the Middle East was a Kurdish woman named Zakiyya Hakki, who was appointed by Abd al-Karim Qasim. She later became part of the leadership of the KDP.[62]

During the Anfal Campaign in 1988, Kurdish women were kept in concentration camps and rape was used as a form of punishment. In 1994, Kurdish women marched for peace from Sulaymaniyah to Erbil in protest against the civil war in Iraqi Kurdistan.[10]

Scholars such as Shahrzad Mojab (1996) and Amir Hassanpour (2001) have argued that the patriarchal system in Iraqi Kurdistan has been as strong as in other Middle Eastern regions.[63][64] [note 1] In 1996, Mojab claimed that the Iraqi Kurdish nationalist movement "discourages any manifestation of womanhood or political demands for gender equality."[63] [note 2] [note 3][note 4]

Contemporary developments[]

After the establishment of Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), women were able to form their own organizations and several women became ministers in the cabinet of local government. In September 2003, Nasrin Berwari was appointed to the 25-member Iraq provisional cabinet as minister of municipalities and public works, and in June 2004, she was among six women named to the 30-member transitional cabinet and in April 2005 was named permanently to that post. As the top Iraqi official in charge of municipal and environmental affairs, Berwari is considered as one of the most important figures in the Iraqi civil administration.[62] However, in the assessment of Dr. Choman Hardi, the director of the Center of Gender and Development at the American University of Iraq - Sulaimani, "although the Kurdistan Regional Government wants to appear progressive and democratic, by granting women their rights, it's still quite superficial and women play a marginal role."[65]

Women's rights activists have said that after the elections in 1992, only five of the 105 elected members of parliament were women, and that women's initiatives were even actively opposed by conservative Kurdish male politicians.[66] Honor killings and other forms of violence against women have increased since the creation of Iraqi Kurdistan, and "both the KDP and PUK claimed that women’s oppression, including ‘honor killings’, are part of Kurdish ‘tribal and Islamic culture’".[66] New laws against honor killing and polygamy were introduced in Iraqi Kurdistan, however it was noted by Amnesty International that the prosecution of honor killings remains low, and the implementation of the anti-polygamy resolution (in the PUK-controlled areas) has not been consistent.[66] On the other hand, it was noted that there are two sides of the same coin of Kurdish nationalism, the patriarchal "conservative nationalist forces", but also the progressive women's movement, which are two sides of the same coin of Kurdish nationalism.[66]

While in the Kurdish areas of Turkey and Syria, women play a dominant role in Kurdistan Communities Union (KCK) affiliated Apoist parties and administrations as co-governors, co-mayors, or even commanded their own female combat units, this never happened in Iraqi Kurdistan, "because the political leadership itself is conservative and patriarchal".[65] However, the Kurdish parties in Iraq there felt embarrassed by the national and international public comparing; in late 2015 an actual female Peshmerga unit for frontline combat was created.[65]

Renowned Kurdish women[]

- Leyla Qasim was a Kurdish activist against the Iraqi Ba'ath regime who was executed in Baghdad. She is known as a national martyr among the Kurds.

- Lanja Khawe is a Kurdish activist and lawyer, who established the social media campaign #KurdishWomenPower and the feminist literacy scheme, the Sofia Association.[67]

Namus-based violence issues[]

Honor killings and other issues[]

In 2008 the United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI) stated that honor killings are a serious concern in Iraq, particularly in Iraqi Kurdistan.[68] The Free Women's Organization of Kurdistan (FWOK) released a statement on International Women's Day 2015 noting that "6,082 women were killed or forced to commit suicide during the past year in Iraqi Kurdistan, which is almost equal to the number of the Peshmerga martyred fighting Islamic State (IS)," and that a large number of women were victims of honor killings or enforced suicide – mostly self-immolation or hanging.[69] Honor killings appear to be particularly prevalent among Iraqi Kurds, Palestinians in Jordan, and in Pakistan and Turkey, but freedom of press in these countries could over-compensate for other countries where the crimes are less reported.[36]

About 500 honour killings per year are reported in hospitals in Iraqi Kurdistan, although real numbers are likely much higher.[70] It is speculated that alone in Erbil there is one honour killing per day.[71] The UNAMI reported that at least 534 honour killings occurred between January and April 2006 in the Kurdish Governorates.[72] It is claimed that many deaths are reported as "female suicides" in order to conceal honour-related crimes.[73] Aso Kamal of the Doaa Network Against Violence claimed that they have estimated that there were more than 12,500 honor killings in Iraqi Kurdistan from 1991 to 2007, and 350 of them in the first part of 2007. He also said that the government figures are much lower, and show a decline in recent years, and Kurdish law has mandated since 2008 that an honor killing be treated like any other murder.[36][74] A medical officer in Sulimaniya reported to the AFP news agency that in May 2008 alone, there were 14 honor killings in 10 days.[36]

The honor killing and self-immolation condoned or tolerated by the Kurdish administration in Iraqi Kurdistan has been labeled as "gendercide" by Mojab (2003).[75][66] In 2005, human rights activist Marjorie P. Lasky claimed that since the PUK and KDP parties took power in Northern Iraq in 1991, "hundreds of women were murdered in honor killings for not wearing hijab and girls could not attend school", and both parties have "continued attempts to suppress the women’s organizations".[76]

Other problems include domestic violence,[77] female infanticide[77] and polygamy.[78] Rural Kurdish women are often not allowed to make their own decisions regarding sexuality or marriage, and in some places child marriages are common.[79][80] Some Kurdish men, and especially religious ones, also practice polygamy.[80] However, polygamy has become less common

almost disappeared from Kurdish culture[citation needed], especially in Syria after Rojava made it illegal. Some Kurdish women from uneducated, religious and poor families who took their own decisions with marriage or had affairs have become victims of violence, including beatings, honor killings and in extreme cases pouring acid on face (only one reported case) (Kurdish Women's Rights Watch 2007).[80][81] There were "7,436 registered complaints of violence against women in Iraq's Kurdish region in 2015", as reported by Al Jazeera. Al Jazeera also noted also that 3,000 women were killed as a result of domestic violence between 2010 and 2015, and in 2015, at least 125 women in six cities in Iraqi Kurdistan committed suicide via self-immolation. Rates of violence against women, female suicide and femicide in Iraqi Kurdistan increased sharply between 2014 and 2015. Almost 200 women were set to fire by someone else in 2015 in the region. Al Jazeera also reported that "44 percent of married women reported being beaten by their husbands if they disobeyed his orders".[82]

Female genital mutilation[]

Female genital mutilation is observed among some Sorani speaking Kurds, including Erbil and Sulaymaniyah.[85] A 2011 Kurdish law criminalized FGM practice in Iraqi Kurdistan and law was accepted four years later.[86][87][88] MICS reported in 2011 that in Iraq, FGM was found mostly among the Kurdish areas in Erbil, Sulaymaniyah and Kirkuk, giving the country a national prevalence of eight percent. However, other Kurdish areas like Dohuk and some parts of Ninewa were almost free from FGM.[89][90][91][88] In 2014, a survey of 827 households conducted in Erbil and Sulaimaniyah assessed a 58.5% prevalence of FGM in both cities. According to the same survey, FGM has declined in recent years.[84][92][93] In 2016, the studies showed that there is a trend of general decline of FGM among those who practiced it before. Kurdish human rights organizations have reported several times that FGM is not a part of Kurdish culture and authorities are not doing enough to stop it completely.[94][better source needed] A 2016 study with 5000 women found that whilst 66 to 99% of women aged 25 or above had been mutilated, the mutilation rate between the ages of 6 and 10 was dramatically lower: 11% in Suleymaniyah and 48% in Raniya, where FGM is the most prevalent and had had rates approaching 100% before the start of the campaign.[95]

According to a 2008 report in the Washington Post, the Kurdistan region of Iraq is one of the few places in the world where female genital mutilation had been rampant.[96] According to one small study carried out in 2008, approximately 60% of all women in northern Iraq had been mutilated.[96] It was claimed that in at least one Kurdish territory, female genital mutilation had occurred among 95% of women.[96] The Kurdistan Region has strengthened its laws regarding violence against women in general and female genital mutilation in particular,[97] and is now considered to be an anti-FGM model for other countries to follow.[98]

Female genital mutilation is prevalent in Iraqi Kurdistan and among Iraqis in central Iraq. In 2010, WADI published a study that 72% of all women and girl in some areas were circumcised that year. Two years later, a similar study was conducted in the province of Kirkuk with findings of 38% FGM prevalence giving evidence to the assumption that FGM was not only practiced by the Kurdish population but also existed in central Iraq. According to the research, FGM is most common among Sunni Muslims, but is also practiced by Shi’ites and Kakeys, while Christians and Yezidi don't seem to practice it in northern Iraq.[99] In Arbil Governorate and Suleymaniya Type I FGM was common; while in Garmyan and New Kirkuk, Type II and III FGM were common.[100][101] There was no law against FGM in Iraq, but in 2007 a draft legislation condemning the practice was submitted to the Regional Parliament, but was not passed.[102] A field report by Iraqi group PANA Center, published in 2012, shows 38% of females in Kirkuk and its surrounding districts areas had undergone female circumcision. Of those females circumcised, 65% were Kurds, 26% Arabs and rest Turkmen. On the level of religious and sectarian affiliation, 41% were Sunnis, 23% Shiites, rest Kaka’is, and none Christians or Chaldeans.[103] A 2013 report finds FGM prevalence rate of 59% based on clinical examination of about 2000 Iraqi Kurdish women; FGM found were Type I, and 60% of the mutilation were performed to girls in 4–7 year age group.[104]

Owing to wars and the unstable situation of country, fighting against FGM has been difficult for authorities of Iraq.[citation needed]

Kurdish women in Iran[]

Background and history[]

During World War I, Kurdish women suffered from attacks of Russian and Turkish armies. In 1915, Russian army massacred the male population of Mahabad and abused two hundred women. Reza Shah issued his decree for coercive unveiling of women in 1936. Government treated the colorful traditional Kurdish female custome as ugly and dirty and it had to be replaced with civilized (i.e. Western) dress. Kurds called this forced dress as Ajami rather than European.[105][106]

Republic of Mahabad encouraged women's participation in public life and KDPI launched a political party for women which promoted education for females and rallied their support for the republic.[107] In August 1979, the Iranian Army launched an offensive to destroy the autonomist movement in Kurdistan. Kurdish organizations such as Komala recruited hundreds of women into their military and political ranks. Within its own camps, Komala abolished gender segregation and women took part in combat and military training.

In 2001, Kurdish researcher Amir Hassanpour claimed that "while it is not unique to the Kurdish case,linguistic, discursive, and symbolic violence against women is ubiquitous" in the Kurdish language, matched by various forms of physical and emotional violence.[80][108]

Contemporary developments[]

In 2001, Kurdish researcher Amir Hassanpour claimed that "while it is not unique to the Kurdish case,linguistic, discursive, and symbolic violence against women is ubiquitous" in the Kurdish language, matched by various forms of physical and emotional violence.[80][108]

Over the years, Kurdish women assumed more roles in the Iranian society and by 2000, a significant number of Kurdish women had become part of the labor force, while an increasing number of females engaged in intellectual activities such as poetry, writing and music. On the other hand, some reports have been made about domestic violence which has led women to commit suicide, most commonly through self-immolation. It is believed that Iran's Islamic culture has been one of the main reasons.[109][110]

Renowned Kurdish women[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (November 2016) |

Namus-based violence issues[]

According to LandInfo, in Iran, honour killings occur primarily among tribal minority groups, such as Kurdish, Lori, Arab, Baluchi and Turkish-speaking tribes. Discriminatory family laws, articles in the Criminal Code that show leniency towards honor killings, and a strongly male dominated society have been cited as causes of honor killings in Iran.[111]

Amnesty International noted in 2008 that the extent and prevalence of violence against women in the Kurdish regions of Iran is impossible to quantify, but "discrimination and violence against women and girls in the Kurdish regions is both pervasive and widely tolerated".[112] According to the UN, discriminatory laws in both the Civil and Penal Codes in Iran play a major role in empowering men and aggravating women's vulnerability to violence. The provisions of the Penal Code relating to crimes specified in the sharia namely, hudud, qisas and diyah, are of particular relevance in terms of gender justice. Many Kurdish organizations have reported that Kurdish women rights in Iran are threatened by Islamic influence.[112] UNICEF's 1998 report found extremely high rates of forced marriage, including at an early age, in Kordestan, although it noted that the practice appeared to be declining.[112] In 2008, self-immolation, "occurred in all the areas of Kurdish settlement (in Iran), where it was more common than in other parts of Iran".[112] It was reported that in 2001, 565 women lost their lives in honor-related crimes in Ilam, Iran, of which 375 were reportedly staged as self-immolation.[112]

In Iran, small-scale surveys show that the Type I and II Female genital mutilation is practiced among Sunni minorities, including Kurds, Azeris and Baloch in the provinces of Kurdistan, Western Azarbaijan, Kermanshah, Illam, Lorestan and Hormozghan. The existing studies have found prevalence rates between 40 and 85% in some provinces.[113][114][115] A 2012 study in Kermanshah province of Iran suggested FGM is a common practice in Ravansars’ women, with over 55% of girls had been circumcised less than 7 years age. The Guardian noted that in West Azerbaijan, FGM occurs among Sunni Shafi’i Kurds of Sorani dialect (but not of Kermanji dialect).[116]

Kurdish women in the diaspora[]

Background and history[]

A major challenge for Kurdish migrants to European countries or North America is the inter-generational transition from a traditional Kurd community, in which the interest of the family is a priority, towards an individualistic society.[117]

Renowned Kurdish women[]

- Widad Akrawi is a Danish health expert and human rights activist of Kurdish ancestry.

- Herro Mustafa is an American diplomat of Kurdish ancestry.

- Feleknas Uca is a Yazidi politician active in Germany and Turkey.

Namus-based violence issues[]

Some honor killings have also been reported among the Kurdish diaspora in the West.[118] According to an article on honour-based violence in the diaspora, published in 2012, "[i]n Europe, many, but by no means all, of the reported honour killings occur in South Asian, Turkish or Kurdish migrant communities".[119]

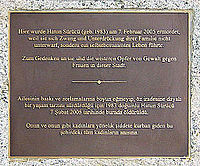

A report published by the Centre for Gender and Violence Research at the University of Bristol and the University of Roehampton in 2010 notes that "it is important to recognize that it is not possible to associate honour-based violence with one particular religion...or culture", but also concludes that "[h]onour-based violence remains prevalent in some Kurdish communities in different locations". The report, which focused on Iraqi Kurdistan and the Kurdish diaspora in the UK, found that "the patriarchal or male-dominated values that underpin these communities often conflict with the values, and even laws, of mainstream UK society. This makes it particularly hard for second or third generation women to define their own values...Instances of HBV [honour-based violence] often result from conflicting attitudes towards life and family codes".[120] Banaz Mahmod, a 20-year-old Iraqi Kurd woman from Mitcham, south London, was killed in 2006, in a murder orchestrated by her father, uncle and cousins.[121] Her life and murder were presented in a documentary called Banaz: A Love Story, directed and produced by Deeyah Khan. Other examples include the first honour killing to be legally recognised in the UK, which was that of Heshu Yones, who was stabbed to death by her Kurdish father in London in 2002 when her family discovered she had a Lebanese Christian boyfriend,[122] and the killing of Tulay Goren, a Kurdish Shia Muslim girl who immigrated with her family from Turkey.[123] In Germany in March 2009, a Kurdish immigrant from Turkey, Gülsüm S., was killed for a relationship not in keeping with her family's plan for an arranged marriage.[124] Two well-known cases from Sweden are the case of Fadime and of Pela. 26-year-old Kurdish woman Fadime Şahindal was killed by her father, a Kurd of the Catholic faith, in 2002.[125][126][127] Kurdish organizations were criticized by prime minister Göran Persson for not doing enough to prevent honour killings.[126] Pela Atroshi was a Kurdish girl from Sweden, who was shot by her uncle in an honour killing while visiting Iraqi Kurdistan.[128] Turkish-Kurdish Hatun Sürücü was murdered at the age of 23 in Berlin, by her own youngest brother, in an honor killing, an incident which led to major public debates in Germany.[129][130][131]

Notes[]

- ^ Pratt writes similarly: "Shahrzad Mojab (2004, 2009), referring to the Iraqi Kurdish context, argues that Islamist-nationalist movements and secular nationalism both stand in the way of transformative gender politics and hinder a feminist analysis of and struggle against gender-based violence and inequalities." https://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/pais/people/pratt/publications/mjcc_004_03_06_al-ali_and_pratt.pdf

- ^ Lasky concluded similarly: "More widely reported are the Iraqi Kurdish nationalist parties’ "disregard of women’s issues and their attempts to suppress women’s organizations", as noted by M. Lasky in 2006."

- ^ Houzan Mahmoud, representative of the Organisation of Women's Freedom in Iraq, voiced similar criticism in 2004, stating that "the Kurdish nationalist parties have violated women's rights and tried to suppress progressive women's organisations. In July 2000, they attacked a women's shelter and the offices of an independent women's organisation. Both were saving the lives of Kurdish women fleeing "honour" killings and domestic violence. More than 8,000 women have died in "honour" killings since the (Kurdish) nationalists have been in control."https://www.theguardian.com/world/2004/mar/08/iraq.gender

- ^ Pratt writes similarly: "There is a link between the Kurdish national struggle and the neglect of women's rights".What Kind of Liberation?: Women and the Occupation of Iraq, Nadje Al-Ali,Nicola Pratt, p.108ff ISBN 978-0-520-26581-3

References[]

- ^ Latif Tas (22 April 2016). Legal Pluralism in Action: Dispute Resolution and the Kurdish Peace Committee. Routledge. p. 31. ISBN 978-1317106159.

- ^ "Kurdish women's movement reshapes Turkish politics – Al-Monitor: the Pulse of the Middle East". Al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ Begikhani, Nazand (24 January 2015). "Why the Kurdish Fight for Women's Rights Is Revolutionary". Huffingtonpost. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ "COMPARING IRAN AND TURKEY IN TERMS OF WOMEN RIGHTS". www.academia.edu. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ^ survival, cultural. "Law and Women in the Middle East". Cultural Survival. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ^ Shahidian, Hammed (2002). Women in Iran: Gender politics in the Islamic republic. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-313-31476-6.

women's rights have been threatened by Islamic influence in iran.

- ^ Charter for the Rights and Freedoms of Women in the Kurdish Regions and Diaspora. Kurdish Human Rights Project. 2004. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-900175-71-5.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Women and Islamic Cultures: Family, Law and Politics, Brill Academic Publishers, 2003

- ^ Encyclopedia of Women and Islamic Cultures: Family, Law and Politics, Brill Academic Publishers, 2003, p. 358ff

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Joseph, Suad; Najmābādi, Afsāneh, eds. (2003), "Kurdish Women", Encyclopaedia of women & Islamic cultures, Boston MA USA: Brill Academic Publishers, pp. 358–360, ISBN 90-04-13247-3

- ^ W. Jwaideh, The Kurdish national movement: its origins and development, 419 pp., Syracuse University Press, 2006. (see p.44)

- ^ "Lady Adela Jaff or the Princess of the Brave". Pukmedia.com. 18 September 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ van Bruinessen, Martin (Fall 1993). "Matriarchy in Kurdistan? Women Rulers in Kurdish History". The International Journal of Kurdish Studies. 6 (1/2): 25–D – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Community Post: 5 Trailblazing Medical Students Of The 19th Century". BuzzFeed Community. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ Bayazidi, M; Rudenko, Margarita Borisovna (1859), Customs and manners of the Kurds, Moscow USSR (published 1963)

- ^ M. Galletti, Western Images of woman's role in Kurdish society in Women of a non-state nation, The Kurds, ed. by Shahrzad Mojab, Costa Mesa Publishers, 2001, pp.209-225.

- ^ V. Minorsky, The Tribes of Western Iran, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, pp.73-80, 1945. (p.78)

- ^ Alakom, Rohat (1995), Kurdish women, A New Force in Kurdistan, Sweden: Spånga Publishers

- ^ MacDowall, David (2004), A Modern History of the Kurds (3rd ed.), London: I.B. Tauris, pp. 207–210, ISBN 1-85043-416-6

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cookman, Liz (24 November 2006). "Women and vulnerable people are paying for Turkey's authoritarianism". The Guardian.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Jenna Krajeski (30 January 2013). "Kurdistan's Female Fighters". The Atlantic.

- ^ Joseph, Suad; Najmābādi, Afsāneh, eds. (2003), "Kurdish Women", Encyclopaedia of women & Islamic cultures, Boston MA USA: Brill Academic Publishers, pp. 361–362, ISBN 90-04-13247-3

- ^ Duzgun, Meral (10 June 2013). "Turkey: a history of sexual violence | Global Development Professionals Network | Guardian Professional". Theguardian.com. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Karaman, Semanur (19 June 2015). "Turkey elections mark the start of a revolution for women". The Guardian.

- ^ "Kurdish women's movement reshapes Turkish politics". Al-Monitor. 25 March 2015. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ Robins-Early, Nick (8 June 2015). "Meet The Pro-Gay, Pro-Women Party Shaking Up Turkish Politics". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Brooks-Pollock, Tom (25 May 2015). "Turkey now has its first ever gay parliamentary candidate". The Independent. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Nordland, Rob (7 December 2016). "Crackdown in Turkey Threatens a Haven of Gender Equality Built by Kurds". New York Times.

- ^ Martens, Michael; Istanbul (20 October 2010). "Bevölkerungsentwicklung: Schafft auch die Türkei sich ab?". FAZ.NET (in German). ISSN 0174-4909.

Bei den Frauen war die Analphabetenrate im Jahr 2000 fast durchweg dreifach so hoch wie bei Männern. Wiederum bot sich besonders im Osten des Landes ein erschreckendes Bild: In Sirnak konnten 66, in Hakkari 58 und in Siirt 56 Prozent der Frauen im Alter von 15 Jahren an nicht lesen und schreiben. In anderen Provinzen der Gegend sah es kaum besser aus.

- ^ Read, Nick (30 August 2005). "The hidden wives of Turkey". BBC News.

- ^ Bilefsky, Dan (10 July 2006). "Polygamy Fosters Culture Clashes (and Regrets) in Turkey". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Letsch, Constanze (10 January 2013). "Sakine Cansiz: 'a legend among PKK members'". The Guardian.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Murat Gezer. "Honor killing perpetrators welcomed by society, study reveals". Today's Zaman. Archived from the original on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b AYSAN SEV’ER. "Feminist Analysis of Honor Killings in Rural Turkey". University of Toronto. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Daughter pregnant by rape, killed by family – World. BrisbaneTimes (13 January 2009). Retrieved on 1 October 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Fisk, Robert (7 September 2010). "The crimewave that shames the world". The Independent. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Rainsford, Sarah (19 October 2005). "'Honour' crime defiance in Turkey". BBC News. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- ^ Boon, Rebecca (2006). "They killed her for going out with boys: Honor killings in Turkey in light of Turkey's accession to the European Union and lessons for Iraq" (PDF). Hofstra Law Review. 35: 815–855.

- ^ Corbin, Bethany A. "Between Saviors and Savages: The Effect of Turkey's Revised Penal Code on the Transformation of Honor Killings into Honor Suicides and Why Community Discourse Is Necessary for Honor Crime Education | Emory University School of Law | Atlanta, GA". Emory University School of Law. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ "Turkey: Letter to Minister Aksu calling for the abolition of the village guards". Human Rights Watch. 7 June 2006.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 November 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Syria". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. p. 13. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Islamic Family Law: Syria (Syrian Arab Republic)". Law.emory.edu. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ^ Berman, Lazar (3 May 2015). "Female Kurdish fighters battling ISIS win Israeli hearts". Rudaw. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ "The Fight Against ISIS in Syria And Iraq December 2014 by Itai Anghel". The Israeli Network via YouTube. 22 December 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ "Fact 2015 (Uvda) – Israel's leading investigative show". The Israeli Network. 22 December 2014. Archived from the original on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ Saeed, Yerevan (26 December 2014). "Kurdish female fighters named 'most inspiring women' of 2014". Rudaw. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ Civiroglu, Mutlu (11 February 2015). "Kobani: How strategy, sacrifice and heroism of Kurdish female fighters beat Isis". International Business Times UK. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ Gol, Jiyar (12 September 2016). "Kurdish 'Angelina Jolie' devalued by media hype". BBC. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Syrian Kurds tackle conscription, underage marriages and polygamy". ARA News. 15 November 2016. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ^ "Syria Kurds challenging traditions, promote civil marriage". ARA News. 20 February 2016. Archived from the original on 22 February 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ^ "Syrian Kurds give women equal rights, snubbing jihadists". Yahoo News. 9 November 2014. Archived from the original on 16 November 2014. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ^ Owen, Margaret (11 February 2014). "Gender and justice in an emerging nation: My impressions of Rojava, Syrian Kurdistan". ceasefiremagazine.co.uk. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ^ "Revolution in Rojava transformed the perception of women in the society". Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ^ Tax, Meredith (14 October 2016). "The Rojava Model". Foreign Affairs.

- ^ "Syrian women liberated from Isis are joining the police to protect their city". The Independent. 13 October 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ "The Cezire Canton: An Arab Sheikh and A Woman Guerrilla at the Helm". Syandan. 4 October 2014. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ^ "Syrian Kurds declare new federation in bid for recognition". Middle East Eye. 17 March 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ^ Kaya, Zeynep (2017). "Gender Equality and the Quest for Statehood in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq" (PDF). LSE Middle East Centre.

- ^ Mojab, Shahrzad (2005). "Kurdish women". In Joseph, Suad (ed.). Encyclopedia of Women and Islamic Cultures: Family, Law and Politics. Volume 2. Leiden: Brill. p. 363. ISBN 978-9004128187.

|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Jump up to: a b Women in the New Iraq Archived 2008-10-05 at the Wayback Machine, by Judith Colp Rubin, Global Politician, September 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b (Mojab 1996:73, Nationalism and Feminism: The Case of Kurdistan, p70-71) fcis.oise.utoronto.ca/~mojabweb/publications/0001E478-80000012/NationalismFeminism.pdf

- ^ "Microsoft Word - 11-HAS~1.doc" (PDF). Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Wladimir van Wilgenburg (3 January 2016). "Kurdish tribal leader breaks taboo by accepting female fighters". Now Media.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e https://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/pais/people/pratt/publications/mjcc_004_03_06_al-ali_and_pratt.pdf

- ^ "Young Kurdish feminists make me hopeful for the future of the region". The Guardian. 7 November 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ "At a Crossroads | Human Rights in Iraq Eight Years after the US-Led Invasion". Human Rights Watch. 21 February 2011. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ "Kurdistan: Over 6,000 Women Killed in 2014". BasNews. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- ^ Kurdish Human Rights Project European Parliament Project: The Increase in Kurdish Women Committing Suicide Final Report Vian Ahmed Khidir Pasha, Member of Kurdistan National Assembly, Member of Women’s Committee, Erbil, Iraq, 25 January 2007

- ^ Kurdish Human Rights Project European Parliament Project: The Increase in Kurdish Women Committing Suicide Final Report Reported by several NGOs and members of Kurdistan National Assembly over course of study to Project Team Member Tanyel B. Taysi.

- ^ http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/etudes/join/2007/393248/IPOL-FEMM_ET(2007)393248_EN.pdf Kurdish Human Rights Project European Parliament Project: The Increase in Kurdish Women Committing Suicide Final Report "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/etudes/join/2007/393248/IPOL-FEMM_ET(2007)393248_EN.pdf Kurdish Human Rights Project European Parliament Project: The Increase in Kurdish Women Committing Suicide Final Report "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 December 2008. Retrieved 18 December 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Leland, John; Abdulla, Namo (20 November 2010). "Honor Killing in Iraqi Kurdistan: Unhealed Wound". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ (PDF). 16 June 2016 https://web.archive.org/web/20160616210850/http://www.kurdipedia.org/documents/87353/0001.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2018. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ Dr. Yasmine Jawad. "The Plight of Iraqi Women, 10 years of suffering" (PDF). S3.amazonaes.com. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b [1] Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ (Refugee Health 2007). Kurdish Refugees From Iraq. Refugee Health. Accessed 5 April 2007. Available from: www3.baylor.edu/~Charles_K...efugees.htm "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 22 February 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 March 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Hassanpour, Amir (2001). "The (Re)production of Kurdish Patriarchy in the Kurdish Language" (PDF). Fcis.oise.utoronto.ca. p. 257. Retrieved 5 April 2007.

- ^ Banaz could have been saved. 20 March 2007. Kurdish Women’s Rights Watch. Accessed 5 April 2007. Available from: www.kwrw.org/index.asp "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 March 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Parvaz, D. (7 October 2016). "Combating domestic violence in Iraq's Kurdish region". Aljazeera.com. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ "Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change - UNICEF DATA" (PDF). Unicef.org. 22 July 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 October 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change - UNICEF DATA" (PDF). UNICEF DATA. 22 July 2013. p. 30.

- ^ "KRG looks to enhance protection of women, children". Al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ "Human Rights Watch lauds FGM law in Iraqi Kurdistan". Ekurd Daily. 26 July 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Iraqi Kurdistan: Law Banning FGM Not Being Enforced". Hrw.org. 29 August 2012. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ UNICEF 2013, pp. 27 (for eight percent), 31 (for the regions)

- ^ Yasin, Berivan A; Al-Tawil, Namir G; Shabila, Nazar P; Al-Hadithi, Tariq S (2013). "Female genital mutilation among Iraqi Kurdish women: A cross-sectional study from Erbil city". BMC Public Health. 13: 809. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-809. PMC 3844478. PMID 24010850.

- ^ "Changing minds about genital mutilation in Iraqi Kurdistan". DW.COM. 3 March 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

Between 41 and 73 percent of women have undergone FGM. A UNICEF report says that more than half of all women between 15 and 49 in the Kurdish governorates of Irbil and Sulimaniyah have undergone FGM.

- ^ "A similar 2013 study concluded that FGM rates for Muslim Kurdish women in Erbil city are very high, with a rate of 58.6%". 7thspace.com. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Yasin, Berivan A.; Al-Tawil, Namir G.; Shabila, Nazar P.; Al-Hadithi, Tariq S. (8 September 2013). "Female genital mutilation among Iraqi Kurdish women: a cross-sectional study from Erbil city". BMC Public Health. 13: 809. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-809. PMC 3844478. PMID 24010850.

- ^ "Female Genital Mutilation: It's a crime not culture". Stopfgmkurdistan.org. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ Wadi (20 October 2013). "Significant Decrease of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) in Iraqi-Kurdistan, New Survey Data Shows". Stop FGM in Kurdistan. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Paley, Amit R. (29 December 2008). "For Kurdish Girls, a Painful Ancient Ritual: The Widespread Practice of Female Circumcision in Iraq's North Highlights The Plight of Women in a Region Often Seen as More Socially Progressive". Washington Post Foreign Service. p. A09.

Kurdistan is the only known part of Iraq --and one of the few places in the world--where female genital mutilation is widespread. More than 60 percent of women in northern Iraq have been mutilated, according to a study conducted this year. In at least one Kurdish territory, 95 percent of women have undergone the practice, which human rights groups call female genital mutilation.

- ^ "KRG looks to enhance protection of women, children". Al-Monitor. 20 April 2015. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ Neurink, Judit (16 June 2015). "Kurdish FGM campaign seen as global model". Rudaw.

- ^ "» Iraq". Stopfgmmideast.org. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ "Female Genital Mutilation in Iraqi Kurdistan – A Study", WADI, accessed 15 February 2010.

- ^ Burki, T (2010). "Reports focus on female genital mutilation in Iraqi Kurdistan". The Lancet. 375 (9717): 794. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60330-3. PMID 20217912. S2CID 9620322.

- ^ "Draft for a Law Prohibiting Female Genital Mutilation is submitted to the Kurdish Regional Parliament", Stop FGM in Kurdistan, accessed 21 November 2010.

- ^ Memorandum to prevent female genital mutilation in Iraq PUK, Kurdistan (May 2, 2013)

- ^ Yasin, Berivan A; Al-Tawil, Namir G; Shabila, Nazar P; Al-Hadithi, Tariq S (2013). "Female genital mutilation among Iraqi Kurdish women: A cross-sectional study from Erbil city". BMC Public Health. 13: 809. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-809. PMC 3844478. PMID 24010850.

- ^ Violence and culture: Confidential records about the abolition of hijab 1934–1943, Iran National Archives, Tehran, 1992, pp.171, 249-250, 273.

- ^ (PDF). 3 November 2004 https://web.archive.org/web/20041103034103/http://www.utoronto.ca/wwdl/publications/english/mojab_introduction.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 November 2004. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ S. Mojab, Women and Nationalism in the Kurdish Republic of 1946 in Women of a non-state nation, The Kurds, ed. by Shahrzad Mojab, Costa Mesa Publishers, 2001, pp.71-91

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Atria". Atria.nl (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 11 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Joseph, Suad; Najmābādi, Afsāneh, eds. (2003), "Kurdish Women", Encyclopaedia of women & Islamic cultures, Boston MA USA: Brill Academic Publishers, p. 363, ISBN 90-04-13247-3

- ^ Esfandiari, Golnaz. "Iran: Self-Immolation Of Kurdish Women Brings Concern (2006)". Rferl.org. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ^ "Honour killings in Iran : Report" (PDF). Landinfo.no. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Document". Amnesty.org. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ "» Iran". Stopfgmmideast.org. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ Golnaz Esfandiari (2009-03-10). "Female Genital Mutilation Said To Be Widespread In Iraq's, Iran's Kurdistan". Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty

- ^ Saleem, R. A., Othman, N., Fattah, F. H., Hazim, L., & Adnan, B. (2013). Female Genital Mutilation in Iraqi Kurdistan: description and associated factors. Women & health, 53(6), 537-551

- ^ Dehghan, Saeed Kamali (4 June 2015). "Female genital mutilation practised in Iran, study reveals". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Tuija Saarinen. "General cultural differences and stereotypes: Kurdish family culture and customs" (PDF). City of Joensuu. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ^ Palash R. Ghosh. "Honor Crimes in Britain Far More Prevalent than Formerly Thought". International Business Times. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ Gill, Aisha K.; Begikhani, Nazand; Hague, Gill (2012). "'Honour'-based violence in Kurdish communities". Women's Studies International Forum. 35 (2): 75–85. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2012.02.001.

- ^ Begikhani, Nazand; Gill, Aisha; Hague, Gill; Ibraheem, Kawther (November 2010). "Final Report: Honour-based Violence (HBV) and Honour-based Killings in Iraqi Kurdistan and in the Kurdish Diaspora in the UK" (PDF). Centre for Gender and Violence Research, University of Bristol and Roehampton University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ "Banaz Mahmod 'honour' killing cousins jailed for life". BBC News. 10 November 2010. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ Rose, Jacqueline (5 November 2009). "A Piece of White Silk". London Review of Books. 31 (21): 5–8.

- ^ Bingham, John (17 December 2009). "Honour killing: father convicted of the killing of Tulay Goren". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^ Schneider, F. (4 March 2009). "Erschlagen, weil sie schwanger war? – Killed, because she was pregnant?". Der Bild.

- ^ Dietz, Maryanna (5 February 2002). "Kurd killing sparks ethnic debate". CNN. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b [2][dead link]

- ^ "Unni Wikan : Das Vermächtnis von Fadime Şahindal" (PDF). Vgs.univie.ac.at. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Powell, Sian (18 March 2009). "Australian links to brutal honour killing". NewsComAu.

- ^ Siemons, Mark (2 March 2005). ""Ehrenmorde": Tatmotiv Kultur". FAZ.NET (in German). ISSN 0174-4909. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Furlong, Ray (14 March 2005). "'Honour killing' shocks Germany". BBC News.

- ^ Goll, Jo (26 July 2011). "Ehrenmord: So brachte Ayhan Sürücü seine Schwester Hatun um". DIE WELT. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

Further reading[]

- Al-Ali, N. S., Pratt, N. C., & Enloe, C. H. (2009). What kind of liberation?: Women and the occupation of Iraq. ISBN 978-0-520-26581-3

- Metin, Y. (2006) The Encounter of Kurdish Women with Nationalism in Turkey

- Nazand Begikhani (2015) Kurdish Women Rights Fight

- Semanur Karaman (2015) Kurdish Women Rights Defenders Continues

- Mojab, S. (2001). Women of a non-state nation: The Kurds. Costa Mesa, Calif: Mazda Publishers.

- Gill, Aisha K.; Begikhani, Nazand; Hague, Gill (2012). "'Honour'-based violence in Kurdish communities". Women's Studies International Forum. 35 (2): 75. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2012.02.001.

- Gill et al. (2010) Honour Based Violence Report IKR and Kurdish Diaspora

- Joseph et al. (2005) Encyclopedia of Women & Islamic Cultures: Family, Law and Politics (p. 358-365)

- Simon Ross Valentine, "Meet the female Kurdish Warrior who battles ISIS", Washington Daily Post, 18 May 2016, http://dailysignal.com/2016/05/18/meet-the-kurdish-female-warrior-who-battles-isis/

External links[]

- "Crackdown in Turkey Threatens a Haven of Gender Equality Built by Kurds", The New York Times, December 2016

- "In Kurdistan and Beyond, Honor Killings Remind Women They Are Worthless", Passblue, 2014

- "Dropping the Knife", BBC documentary on Female Genital Mutilation in Northern Iraq, 2013

- "They Took Me and Told Me Nothing", Human Rights Watch on Female Genital Mutilation in Iraqi Kurdistan, 2010

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kurdish women. |

- Kurdish women

- Kurdish people

- Middle Eastern women

- Women in Iraq

- Women in Iran

- Women in Turkey

- Women in Syria