Māori electorates

Politics of New Zealand |

|---|

|

|

In New Zealand politics, Māori electorates, colloquially known as the Māori seats, are a special category of electorate that until 1967 gave reserved positions to representatives of Māori in the New Zealand Parliament. Every area in New Zealand is covered by both a general and a Māori electorate; as of 2020, there are seven Māori electorates.[1][2] Since 1967 any candidate of any ethnicity has been able to stand in a Maori electorate. Candidates now do not have to be Māori, or even on the Māori roll. Voters however who wish to vote in a Māori electorate have to register as a voter on the Māori roll and need to declare they are of Māori descent.[3]

The Māori electorates were introduced in 1867 under the Maori Representation Act.[4] They were created in order to give Māori a more direct say in parliament. The first Māori elections were held in the following year during the term of the 4th New Zealand Parliament. The electorates were intended as a temporary measure lasting five years but were extended in 1872 and made permanent in 1876.[5] Despite numerous attempts to dismantle Māori electorates, they continue to form a distinct part of the New Zealand political landscape.[6]

Organisation[]

Māori electorates operate much as do general electorates, but have as electors people who are Māori or of Māori descent, and who choose to place their names on a separate electoral roll rather than on the "general roll".

There are two features of the Māori electorates that make them distinct from the general electorates. First, there are a number of skills that are essential for candidates to have in order to engage with their constituencies and ensure a clear line of accountability to representing the 'Māori voice'. This includes proficiency in the Māori language, knowledge of tikanga Māori, whakawhanaungatanga skills and confidence on the marae. Second, the geographical size of the Māori electoral boundaries vary significantly from the general electorates. Five to 18 general electorates fit into any one Māori electorate.[7]

Māori electoral boundaries are superimposed over the electoral boundaries used for general electorates; thus every part of New Zealand simultaneously belongs both in a general seat and in a Māori seat. Shortly after each census all registered Māori electors have the opportunity to choose whether they are included on the Māori or General electorate rolls.[8] Each five-yearly Māori Electoral Option determines the number of Māori electorates for the next one or two elections.

Establishment[]

The establishment of Māori electorates came about in 1867 during the term of the 4th Parliament with the Maori Representation Act, drafted by Napier member of parliament Donald McLean.[6] Parliament passed the Act only after lengthy debate, it was passed during a period of warfare between the Government and several North Island Māori tribes, and was seen as a way to reduce conflict between the races in future.[9] The act originally agreed to set up four electorates specially for Māori, three in the North Island and one covering the whole South Island.[10] The four seats were a fairly modest concession on per capita basis at the time.[10]

Many conservative MPs, most of whom considered Māori "unfit" to participate in government, opposed Māori representation in Parliament, while some MPs from the other end of the spectrum (such as James FitzGerald, who had proposed allocating a third of Parliament to Māori) regarded the concessions given to Māori as insufficient. In the end the setting up of Māori electorates separate from existing electorates assuaged conservative opposition to the bill – conservatives had previously feared that Māori would gain the right to vote in general electorates, thereby forcing all MPs (rather than just four Māori MPs) to take notice of Māori opinion.

Before this law came into effect, no direct prohibition on Māori voting existed, but other indirect prohibitions made it extremely difficult for Māori to exercise their theoretical electoral rights. The most significant problem involved the property qualification – to vote, one needed to possess a certain value of land.[7] Māori owned a great deal of land, but they held it in common, not under individual title, and under the law, only land held under individual title could count towards the property qualification.[11] Donald McLean explicitly intended his bill as a temporary measure, giving specific representation to Māori until they adopted European customs of land ownership. However, the Māori electorates lasted far longer than the intended five years, and remain in place today, despite the property qualification for voting being removed in 1879.

The first four Māori members of parliament elected in 1868 were Tāreha te Moananui (Eastern Maori), Frederick Nene Russell (Northern Maori) and John Patterson (Southern Maori), who all retired in 1870; and Mete Kīngi Te Rangi Paetahi (Western Maori) who was defeated in 1871. These four persons were the first New Zealand-born members of the New Zealand Parliament.[12] The second four members were Karaitiana Takamoana (Eastern Maori); Wi Katene (Northern Maori); Hōri Kerei Taiaroa (Southern Maori); and Wiremu Parata (Western Maori).[13]

The first Māori woman MP was Iriaka Rātana who represented the enormous Western Māori electorate. Like Elizabeth McCombs, New Zealand's first woman MP, Ratana won the seat in a hotly contested by-election caused by the death of her husband Matiu in 1949.[14]

Elections[]

Currently Māori elections are held as part of New Zealand general elections but in the past such elections took place separately, on different days (usually the day before the vote for general electorates) and under different rules. Historically, less organisation went into holding Māori elections than general elections, and the process received fewer resources. Māori electorates at first did not require registration for voting, which was later introduced. New practices such as paper ballots (as opposed to casting one's vote verbally) and secret ballots also came later to elections for Māori electorates than to general electorates.

The authorities frequently delayed or overlooked reforms of the Māori electoral system, with Parliament considering the Māori electorates as largely unimportant. The gradual improvement of Māori elections owes much to long-serving Māori MP Eruera Tirikatene, who himself experienced problems in his own election. From the election of 1951 onwards, the voting for Māori and general electorates was held on the same day.[15]

Confusion around the Māori electorates during the 2017 general election was revealed in a number of complaints to the Electoral Commission. Complaints included Electoral Commission staff at polling booths being unaware of the Māori roll and insisting electors were unregistered when their names did not appear on the general roll; Electoral Commission staff giving incorrect information about the Māori electorates; electors being given incorrect voting forms and electors being told they were unable to vote for the Māori Party unless they were on the Māori roll.[16]

Calls for abolition[]

Periodically there have been calls for the abolition of the Māori electorates. The electorates aroused controversy even at the time of their origin, and given their intended temporary nature, there were a number of attempts to abolish them. The reasoning behind these attempts has varied – some have seen the electorates as an unfair or unnecessary advantage for Māori, while others have seen them as discriminatory and offensive.

Early 20th century[]

In 1902, a consolidation of electoral law prompted considerable discussion of the Māori electorates, and some MPs proposed their abolition. Many of the proposals came from members of the opposition, and possibly had political motivations – in general, the Māori MPs had supported the governing Liberal Party, which had held power since 1891. Many MPs alleged frequent cases of corruption in elections for the Māori electorates. Other MPs, however, supported the abolition of Māori electorates for different reasons – Frederick Pirani, a member of the Liberal Party, said that the absence of Māori voters from general electorates prevented "pākehā members of the House from taking that interest in Māori matters that they ought to take". The Māori MPs, however, mounted a strong defence of the electorates, with Wi Pere depicting guaranteed representation in Parliament as one of the few rights Māori possessed not "filched from them by the Europeans". The electorates continued in existence.

Just a short time later, in 1905, another re-arrangement of electoral law caused the debate to flare up again. The Minister of Māori Affairs, James Carroll, supported proposals for the abolition of Māori electorates, pointing to the fact that he himself had won the general electorate of Waiapu. Other Māori MPs, such as Hone Heke Ngapua, remained opposed, however. In the end, the proposals for the abolition or reform of Māori electorates did not proceed.

Mid 20th century[]

Considerably later, in 1953, the first ever major re-alignment of Māori electoral boundaries occurred, addressing inequalities in voter numbers. Again, the focus on Māori electorates prompted further debate about their existence. The government of the day, the National Party, had at the time a commitment to the assimilation of Māori, and had no Māori MPs, and so many believed that they would abolish the electorates. However, the government had other matters to attend to, and the issue of the Māori electorates gradually faded from view without any changes. Regardless, the possible abolition of the Māori electorates appeared indicated when they did not appear among the electoral provisions entrenched against future modification.

In the 1950s the practice of reserving electorates for Māori was described by some politicians "as a form of 'apartheid', like in South Africa".[17]

In 1967, the electoral system whereby four electorate seats were reserved for representatives who were specifically Māori ended. Following the Electoral Amendment Act of 1967, the 100-year-old disqualification preventing Europeans from standing as candidates in Māori electorates was removed. (The same Act allowed Māori to stand in European electorates.)

Since 1967, therefore, there has not been any electoral guarantee of representation by candidates who have Māori descent. While this still means that those elected to represent Māori electors in the Māori electorates are directly accountable to those voters[clarification needed], those representatives are not required to themselves be Māori.[18]

In 1976, Māori gained the right for the first time to decide on which electoral roll they preferred to enrol. Surprisingly, only 40% of the potential population registered on the Māori roll. This reduced the number of calls for the abolition of Māori electorates, as many presumed that Māori would eventually abandon the Māori electorates of their own accord.[citation needed]

However the 1977 electoral redistribution has been described as the most overtly political since the Representation Commission was established (through an amendment to the Representation Act in 1886); the option to decide which roll to go on was introduced by Muldoon's National Government.[19] As part of the 1976 census, a large number of people failed to fill out an electoral re-registration card, and census staff had not been given the authority to insist on the card being completed. This had little practical effect for people on the general roll, but it transferred Māori to the general roll if the card was not handed in.

1986 Royal Commission[]

When a Royal Commission proposed the adoption of the MMP electoral system in 1986, it also proposed that if the country adopted the new system, it should abolish the Māori electorates. The Commission argued that under MMP, all parties would have to pay attention to Māori voters, and that the existence of separate Māori electorates marginalised Māori concerns. Following a referendum, Parliament drafted an Electoral Reform Bill, incorporating the abolition of the Māori electorates. Both the National Party and Geoffrey Palmer, Labour's leading reformist, supported abolition; but most Māori strongly opposed it. Eventually, the provision did not become law. The Māori electorates came closer than ever to abolition, but survived.

Current positions[]

A number of currently active political parties oppose, or have opposed, the existence of Māori electorates.

National Party[]

The National Party has advocated abolition of the separate electorates, though its more recent positions is that they are not opposed to the seats. National did not stand candidates in Māori electorate from the 2005 election through the 2020 election. The party's leader in 2003, Bill English, said that "the purpose of the Māori seats has come to an end", and its leader in 2004, Don Brash, call the electorates an "anachronism".[20] National announced in 2008 it would abolish the electorates when all historic Treaty settlements have been resolved, which it aimed to complete by 2014.[21] In 2014 though, then-Prime Minister John Key ruled it out, saying he would not do it even if he had the numbers to do so as there would be "hikois from hell".[22] In 2020, party leader Judith Collins announced that "I am not opposed to the Māori seats. The National Party has had a view for many years now that they should be done away with. But I just want people to feel that they all have opportunities for representation".[23] In 2021, it was revealed that the National Party intended to run candidates in Māori electorates in the next general election.[20]

ACT Party[]

The ACT Party opposes the Māori electorates. Its leader, David Seymour, has called for their abolishment as recently as 2019.[24] Also, a lobby group founded by former ACT Party leader Don Brash called Hobson's Pledge advocates abolishing the allocated Māori electorates, seeing them as outdated.[25]

New Zealand First[]

New Zealand First has advocated for abolition of the separate electorates but says that the Māori voters should make the decision. During the 2017 election campaign, the New Zealand First leader Winston Peters announced that if elected his party would hold a binding referendum on whether Maori electorates should be abolished.[26] During post-election negotiations with the Labour Party, Peters indicated that he would consider dropping his call for a referendum on the Māori electorates due to the defeat of the Māori Party at the 2017 election.[27] In return for forming a government with the Labour Party, NZ First agreed to drop its demand for the referendum.[28][29]

Number of electorates[]

From 1868 to 1996, four Māori electorates existed (out of a total that slowly changed from 76 to 99).[30] They comprised:[31]

With the introduction of the MMP electoral system after 1993, the rules regarding the Māori electorates changed. Today, the number of electorates floats, meaning that the electoral population of a Māori seat can remain roughly equivalent to that of a general seat. In the first MMP vote (the 1996 election), the Electoral Commission defined five Māori electorates:

- Te Puku O Te Whenua (The belly of the land)

- Te Tai Hauauru (The western district)

- Te Tai Rawhiti (The eastern district)

- Te Tai Tokerau (The northern district)

- Te Tai Tonga (The southern district)

A sixth Māori electorate was added for the second MMP election in 1999:

- Hauraki

- Ikaroa-Rawhiti

- Te Tai Hauāuru

- Te Tai Tokerau

- Te Tai Tonga

- Waiariki

Since 2002, there have been seven Māori electorates. For the 2002 and 2005 elections, these were:

- Ikaroa-Rāwhiti

- Tainui

- Tāmaki Makaurau (roughly equivalent to greater Auckland)

- Te Tai Hauāuru

- Te Tai Tokerau

- Te Tai Tonga

- Waiariki

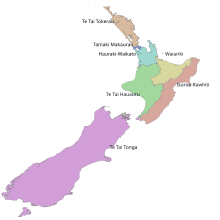

From 2008, Tainui was largely replaced by Hauraki-Waikato, giving the following seven Māori electorates:

- Hauraki-Waikato – (North Western North Island, includes Hamilton and Papakura)

- Ikaroa-Rāwhiti – (East and South North Island, includes Gisborne and Masterton)

- Tāmaki Makaurau – (Roughly equivalent to greater Auckland)

- Te Tai Hauāuru – (Western North Island, includes Taranaki and Manawatū-Whanganui regions)

- Te Tai Tokerau – (Northernmost seat, includes Whangārei and North and West Auckland)

- Te Tai Tonga – (All of South Island and nearby islands. Largest electorate by area)

- Waiariki – (Includes Tauranga, Whakatāne, Rotorua, Taupo)

While seven out of 70 (10%) does not nearly reflect the proportion of New Zealanders who identify as being of Māori descent (about 18%), many Māori choose to enroll in general electorates, so the proportion reflects the proportion of voters on the Māori roll.

For maps showing broad electoral boundaries, see selected links to individual elections at New Zealand elections.

Former Māori Party co-leader Pita Sharples proposed the creation of an additional electorate, for Māori living in Australia, where there are between 115,000 and 125,000 Māori, the majority living in Queensland.[32]

Party politics[]

As Māori electorates originated before the development of political parties in New Zealand, all early Māori MPs functioned as independents. When the Liberal Party formed, however, Māori MPs began to align themselves with the new organisation, with either Liberal candidates or Liberal sympathisers as representatives. Māori MPs in the Liberal Party included James Carroll, Āpirana Ngata and Te Rangi Hīroa. There were also Māori MPs in the more conservative and rural Reform Party; Maui Pomare, Taurekareka Henare and Taite Te Tomo.

Since the Labour Party first came to power in 1935, however, it has dominated the Māori electorates. For a long period this dominance owed much to Labour's alliance with the Rātana Church, although the Rātana influence has diminished in recent times. In the 1993 election, however, the new New Zealand First party, led by the part-Māori Winston Peters – who himself held the general seat of Tauranga from 1984 to 2005 – gained the Northern Māori seat (electing Tau Henare to Parliament), and in the 1996 election New Zealand First captured all the Māori electorates for one electoral term. Labour regained the electorates in the following election in the 1999 election.[7]

A development of particular interest to Māori came in 2004 with the resignation of Tariana Turia from her ministerial position in the Labour-dominated coalition and from her Te Tai Hauāuru parliamentary seat. In the resulting by-election on 10 July 2004, standing under the banner of the newly formed Māori Party, she received over 90% of the 7,000-plus votes cast. The parties then represented in Parliament had not put up official candidates in the by-election. The new party's support in relation to Labour therefore remained untested at the polling booth.[33]

The Māori Party aimed to win all seven Māori electorates in 2005. A survey of Māori-roll voters in November 2004 gave it hope: 35.7% said they would vote for a Māori Party candidate, 26.3% opted for Labour, and five of the seven electorates appeared ready to fall to the new party.[34] In the election, the new party won four of the Māori electorates. It seemed possible that Māori Party MPs could play a role in the choice and formation of a governing coalition, and they conducted talks with the National Party. In the end they remained in Opposition.[35]

Similarly in 2008, the Māori Party aimed to win all seven Māori electorates. However, in the election, they managed to increase their four electorates only to five. Although the National government had enough MPs to govern without the Māori Party, it invited the Māori Party to support their minority government on confidence and supply in return for policy concessions and two ministerial posts outside of Cabinet. The Māori Party signed a confidence and supply agreement with National on the condition that the Māori electorates were not abolished unless the Māori voters agreed to abolish them. Other policy concessions including a review of the Foreshore and Seabed Act 2004, a review of New Zealand's constitutional arrangements, and the introduction of the Whānau Ora indigenous health initiative.[36]

Discontentment with the Māori Party's support agreement with National particularly the Marine and Coastal Areas Bill 2011 led the party's Te Tai Tokerau Member Hone Harawira to secede from the Māori Party and form the radical left-wing Mana Movement. During the 2011 general election, the Māori Party retained three of the Māori electorates while Labour increased its share of the Māori electorates to three, taking Te Tai Tonga. The Mana Movement retained Te Tai Tokerau. Tensions between the Māori Party and Mana Movement combined with competition from the Labour Party fragmented the Māori political voice in Parliament.[37][38]

In the 2014 election, Mana Movement leader Hone Harawira formed an electoral pact with the Internet Party, founded by controversial Internet entrepreneur Kim Dotcom and led by former Alliance MP Laila Harré known as Internet MANA. Hone was defeated by Labour candidate Kelvin Davis, who was tacitly endorsed by the ruling National Party, New Zealand First, and the Māori Party.[39][40][41][42] During the 2014 election, Labour captured six of the Māori electorates with the Māori Party being reduced to co-leader Te Ururoa Flavell's Waiariki electorate.[43] The Māori Party managed to bring a second member co-leader Marama Fox into Parliament as their party vote entitled them to one further list seat.[44]

During the 2017 general election, the Māori Party formed an electoral pact with the Mana Movement leader and former Māori Party MP Hone Harawira not to contest Te Tai Tokerau as part of a deal to regain the Māori electorates from the Labour Party.[45] Despite these efforts, Labour captured all seven of the Māori electorates with Labour candidate Tamati Coffey unseating Māori Party co-leader Flavell in Waiariki.[46]

Three years later, despite a historic landslide to the Labour party, Māori party candidate Rawiri Waititi successfully unseated Coffey, returning the Māori Party to Parliament. Special votes raised the Māori Party vote from a provisional result of 1%[47] to a final party vote of 1.2%, thus allowing co-leader, Debbie Ngarewa-Packer, to enter Parliament as a List MP.[48]

See also[]

- New Zealand elections

- Māori politics

- Local government in New Zealand#Māori wards and constituencies

References[]

- ^ "Change in the 20th century". Māori and the vote. New Zealand History. p. 3.

- ^ "Number of Electorates and Electoral Populations: 2013 Census". Stats NZ. 7 October 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ^ "About the Māori Electoral Option". Electoral Commission New Zealand. 17 September 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ "Maori Representation Act 1867". Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ^ "Representation Act 1867". archives.govt.nz.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wilson, John (31 May 2009) [November 2003]. "The Origins of the Māori Seats". Wellington: New Zealand Parliament. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bargh 2015, pp. 302–303.

- ^ "Māori Electoral Option 2013 | Electoral Commission". Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ^ "Maori Representation Act 1867". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Setting up the Māori seats". Maori and the Vote. New Zealand History. p. 2.

- ^ "The origins of the Māori seats". New Zealand Parliament – Pāremata Aotearoa.

- ^ Scholefield, Guy, ed. (1940). A Dictionary of New Zealand Biography : M–Addenda (PDF). II. Wellington: Department of Internal Affairs. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- ^ Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "1. – Ngā māngai – Māori representation – Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand". teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- ^ "First Māori woman MP (3rd of 4)". teara.govt.nz.

- ^ Wilson 1985, p. 138.

- ^ "Polling booth staff mislead and confuse Māori voters". Māori Television. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- ^ "History of the Vote: Māori and the Vote". Elections New Zealand. 9 April 2005. Archived from the original on 29 April 2007. Retrieved 3 November 2006.

In the 1950s and 1960s the National government occasionally talked of abolishing the Māori seats. Some politicians described special representation as a form of 'apartheid', like in South Africa.

- ^ Wilson, John. "Origin of the Maori Seats".

- ^ McRobie 1989, pp. 8–9, 51, 119.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sherman, Maiki (28 January 2021). "Exclusive: National Party to contest Māori electorate seats". TVNZ. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ^ Tahana, Yvonne (29 September 2008). "National to dump Maori seats in 2014". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 28 December 2009.

- ^ "John Key: Dropping Maori seats would mean 'hikois from hell'". The New Zealand Herald. 22 August 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- ^ "Judith Collins keen to run candidates in the Māori seats, tear up the RMA, but not cut benefits". Stuff News. 16 July 2020.

- ^ Walls, Jason (14 April 2019). "Act Leader David Seymour: Kiwis need to resist an 'Orwellian future'". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ^ "Maori seats outdated". Hobson's Choice. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- ^ Moir, Jo (16 July 2017). "Winston Peters delivers bottom-line binding referendum on abolishing Maori seats". Stuff. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ Burrows, Matt (28 September 2017). "Winston Peters hints at U-turn on Māori seat referendum". Newshub. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ Cheng, Derek (30 October 2017). "Anti-smacking referendum dropped during coalition negotiations". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ Guy, Alice (21 October 2017). "Local kaumatua not surprised Maori seats will be retained". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^ "General elections 1853–2005 – dates & turnout". Elections New Zealand. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ^ Scholefield, Guy (1950) [First ed. published 1913]. New Zealand Parliamentary Record, 1840–1949 (3rd ed.). Wellington: Govt. Printer. pp. 157, 161, 163, 167.

- ^ "Maori Party suggests seat in Aust". Television New Zealand. Newstalk ZB. 1 October 2007. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ^ Bargh 2015, pp. 305–306.

- ^ "Marae DigiPoll1_02.03.08". TVNZ. 2 March 2008. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ Godfery 2015, pp. 243–244.

- ^ Godfery 2015, pp. 244–245.

- ^ Godfery 2015, pp. 245–248.

- ^ Bargh 2015, p. 305.

- ^ Bennett, Adam (21 September 2014). "Election 2014: Winston Peters hits out at National after big poll surge". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ^ McQuillan, Laura (17 September 2014). "Key's subtle endorsement for Kelvin Davis". Newstalk ZB. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ^ "Davis picking up endorsements". Radio Waatea. 19 September 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ^ Smith, Simon (20 September 2014). "Davis' win a critical blow for Harawira, Internet Mana". Stuff. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ^ Godfery 2015, p. 249.

- ^ "New Zealand 2014 General Election Official Results". Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ Moir, Jo (20 February 2017). "Hone Harawira gets clear Te Tai Tokerau run for Mana not running against Maori Party in other seats". Stuff. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ Huffadine, Leith (24 September 2017). "The Maori Party is out: Labour wins all Maori seats". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "Election 2020: Labour claims victory, National has worst result in years". RNZ. 17 October 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ "'Thrilled' Debbie Ngarewa-Packer enters Parliament on special votes". RNZ. 6 November 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

Further reading[]

- Bargh, Maria (2015). "Chapter 5.3: The Māori Seats". In Hayward, Janine (ed.). New Zealand Government and Politics, Sixth Edition. Oxford University Press. pp. 300–310. ISBN 9780195585254.

- Godfery, Morgan (2015). "Chapter 4.4: The Māori Party". In Hayward, Janine (ed.). New Zealand Government and Politics, Sixth Edition. Oxford University Press. pp. 240–250. ISBN 9780195585254.

- McRobie, Alan (1989). Electoral Atlas of New Zealand. Wellington: GP Books. ISBN 0-477-01384-8.

- Wilson, James Oakley (1985) [1913]. New Zealand Parliamentary Record, 1840–1984 (4th ed.). Wellington: V.R. Ward, Govt. Printer. OCLC 154283103.

- Māori electorates

- Māori politics

- Parliament of New Zealand

- Race relations in New Zealand