Makhnovshchina

Makhnovshchina Махновщина | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1918–1921 | |||||||||

Flag described by Viktor Belash

Emblem used on currency stamps

| |||||||||

| Motto: "Power begets parasites. Long live Anarchy!" | |||||||||

Location of the core of Makhnovia (red) and other areas controlled by the Black Army (pink) in present-day Ukraine (tan) | |||||||||

| Status | Stateless territory | ||||||||

| Capital | Huliaipole | ||||||||

| Common languages | Ukrainian Russian | ||||||||

| Government | Anarcho-Communist[1] | ||||||||

| Military leader | |||||||||

• 1918–1921 | Nestor Makhno | ||||||||

| Historical era | Russian Civil War | ||||||||

• Established | 27 November 1918 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 28 August 1921 | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• Estimate | 7 million | ||||||||

| Currency | unknown | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Ukraine | ||||||||

| History of Ukraine |

|---|

|

|

|

Makhnovshchina or Makhnovia (Ukrainian: Махновщина, romanized: Makhnovshchyna; Russian: Махновщина, romanized: Makhnovshchina), resulted from an attempt to form a stateless anarchist[1] society in parts of Ukraine during the Russian Revolution of 1917–1923. It existed from 1918 to 1921, during which time free soviets and libertarian communes[2] operated under the protection of Nestor Makhno's Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army. The area had a population of around seven million.[3]

Makhnovia was established with the capture of Huliaipole by Makhno's forces on 27 November 1918. An insurrectionary staff was set up in the city, which became the territory's de facto capital.[4] Russian forces of the White movement, under Anton Denikin, occupied part of the region and formed a temporary government of Southern Russia in March 1920, resulting in the de facto capital being briefly moved to Katerynoslav (modern-day Dnipro). In late March 1920, Denikin's forces retreated from the area, having been driven out by the Red Army in cooperation with Makhno's forces, whose units conducted guerrilla warfare behind Denikin's lines. Makhnovia was disestablished on 28 August 1921, when a badly-wounded Makhno and 77 of his men escaped through Romania after several high-ranking officials were executed by Bolshevik forces. Remnants of the Black Army continued to fight until late 1922.

As Makhnovia self-organized along anarchist principles, references to "control" and "government" are highly contentious. For example, the Makhnovists, often cited as a form of government (with Makhno as their "leader"), played a purely military role, with Makhno himself functioning as little more than a military strategist and advisor.[5]

History[]

The emergence of the Makhnovist movement and Makhnovia[]

Following his liberation from prison during the February Revolution in 1917, Makhno returned to his hometown of Huliaipole and organized a peasants' union.[6] It gave him a "Robin Hood" image and he expropriated large estates from landowners and distributed the land among the peasants.[6] Makhno joined an anarchist group called the Black Guards (headed by sailor-deserter Fedir Shchus) and eventually became its commander.

In March 1918, the new Bolshevik government in Russia signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk concluding peace with the Central Powers, but ceding large amounts of territory, including Ukraine. As the Central Rada of the new Ukrainian People's Republic (UNR) proved unable to maintain order, a coup by Pavlo Skoropadsky in April 1918 resulted in the establishment of the Hetmanate. Already dissatisfied with the UNR's failure to resolve the question of land ownership, much of the peasantry refused to support a conservative government administered by former imperial officials and supported by the Austro-Hungarian and German occupiers. The Hetman lost the support of the Central Powers (Germany and Austria-Hungary, which had armed his forces and installed him in power) after the collapse of the German western front. Unpopular among most southern Ukrainians, he saw his best forces evaporate, and was driven out of Kyiv by the Directorate of Ukraine.[7] Peasant bands under various self-appointed otamany which had once been counted on the rolls of the UNR's army now attacked the Germans.[8] These warlords finally came to dominate the countryside; some defected to the directory or the Bolsheviks, but the largest portion followed either socialist revolutionary Matviy Hryhoriyiv or the anarchist flag of Makhno.[8]

At this point, the emphasis on military campaigns that Makhno had adopted in the previous year shifted to political concerns. The first Congress of the Confederation of Anarchists Groups, under the name of "Nabat" (the alarm bell toll), issued five main principles: rejection of all political parties, rejection of all forms of dictatorships, negation of any concept of a central state, rejection of a so-called "transitional period" necessitating a temporary dictatorship of the proletariat, and self-management of all workers through free local workers' councils (soviets). After recruiting large numbers of Ukrainian peasants, as well as numbers of Jews, anarchists, naletchki, and recruits arriving from other countries, Makhno formed the Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine, otherwise known as the "Anarchist Black Army". At its formation, the Black Army consisted of about 15,000 armed troops, including infantry and cavalry (both regular and irregular) brigades; artillery detachments were incorporated into each regiment. The RIAU battled against the White Army, Ukrainian nationalists, and various independent paramilitary formations that conducted anti-semitic pogroms.

The November Revolution of 1918 led to Germany's defeat in the First World War. By this time, Makhno was leading a rebel movement of 6,000 people against the German Empire in the Yekaterinoslav province,[9] while the German troops themselves were demoralized and did not want to fight, leading them to withdraw swiftly. On November 27, Makhno occupied Huliaipole, declared it in a state of siege, and formed the "Huliaipole Revolutionary Headquarters". The rebels by this time represented considerable strength, controlling most of the territory of the Yekaterinoslav province.[9] According to Makhno, "The agricultural majority of these villages was composed of peasants, one would understand at the same time both peasants and workers. They were founded first of all on equality and solidarity of its members. Everyone, men and women, worked together with a perfect conscience that they should work on fields or that they should be used in housework... The work program was established in meetings in which everyone participated. Then they knew exactly what they had to do". (Makhno, Russian Revolution in Ukraine, 1936).

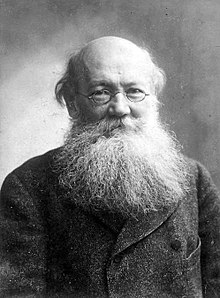

Society was reorganized according to anarchist values, which led Makhnovists to formalize the policy of free communities as the highest form of social justice. Education followed the principles of Francesc Ferrer, and the economy was based on free exchange between rural and urban communities, from crops and cattle to manufactured products, according to the theories of Peter Kropotkin.

The Makhnovists said they supported "free worker-peasant soviets"[10] and opposed the central government. Makhno called the Bolsheviks "dictators" and opposed the "Cheka... and similar compulsory authoritative and disciplinary institutions". He called for "freedom of speech, press, assembly, unions and the like".[10] The Makhnovists called various congresses of soviets, in which all political parties and groups – including Bolsheviks – were permitted to participate, to the extent that members of these parties were elected delegates from worker, peasant or militia councils. By contrast, in Bolshevik territory after June 1918, no non-Bolsheviks were permitted to participate in any national soviets and most local ones,[11] the decisions of which were also all subject to Bolshevik party veto.

A declaration stated that Makhnovist revolutionaries were forbidden to participate in the Cheka, and all party-run militias and party police forces (including Cheka-like secret police organizations) were to be outlawed in Makhnovist territory.[12][13] Historian Heather-Noël Schwartz comments that "Makhno would not countenance organizations that sought to impose political authority, and he accordingly dissolved the Bolshevik revolutionary committees".[14][15] The Bolsheviks, however, accused him of having two secret police forces operating under him.[16]

Meanwhile, the Petliurites, who formed their army from many conscripted rebel groups and seized power in a number of Ukrainian cities, considered the Makhnovist movement an integral part of the all-Ukrainian national revolution and hoped to draw it into the sphere of their influence and leadership. However, when he received a proposal from the Directorate of Ukraine about joint actions against the Red Army, Makhno answered: "Petlyurovschina is a gamble that distracts the attention of the masses from the revolution." According to Makhno and his comrades-in-arms, Petliurism was a movement of the Ukrainian national bourgeoisie, with which the people's revolutionary movement was completely out of step.[17]

On 26 December, Makhno's detachments, together with the armed detachments of the Yekaterinoslav Provincial Committee of the Bolshevik Party, forced the Petliurists out of Yekaterinoslav. However, taking advantage of the carelessness of the rebel command, the Petliurites returned, and after two or three days expelled the Makhnovists from the city. The Makhnovists retreated to the Synelnykove district. From that moment on the northwestern border of the territory controlled by Makhno, a front arose between the Makhnovists and Petliurists. However, due to the fact that Petliura's troops, consisting mostly of conscripted rebel peasants, began to quickly decompose on contact with the Makhnovists, the front was soon liquidated.[17]

After the Yekaterinoslav operation the Makhnovists settled in Huliaipole, where Makhno planned to begin practical implementation of the anarchist ideal – the creation of a free, stateless communist society in the Huliaipole district. However, the position of the rebels was not yet secure; the Petliurites continued to exert pressure on Makhno trying to lure him to their side, General Denikin was approaching from the south, and the was approaching Makhnovist territory from the north. Therefore, Makhno tried to bide time, strengthen his own force at the expense of potential allies and find a more profitable line of behavior.[18]

On 12 January, the White Army launched an attack on the Makhnovist district from Donbass. They took it on 20 January, and attacked Huliaipole on 21–22 January. In this situation, Makhno finally decided to make an alliance with the Reds, declaring the Petliurites and Denikinists as the most dangerous opponents. The agreement with the Red Army was considered by Makhno as exclusively military, not affecting the social structure of the Makhnovist district.[17]

As part of the Ukrainian Front, Makhno's brigade participated in battles with the White Guards in Donbass and in the Sea of Azov. As a result of the Black Army's advance, the territory controlled by them increased to 72 volosts of the Yekaterinoslav province with a population of more than two million people. Makhno was just as rebellious towards the Red command as he was to the White, constantly emphasizing independence. The Makhnovists set up detachments on the railroad and intercepted wagons with flour, bread, other food products, coal, and straw. Moreover, they themselves refused to sell bread from the surplus stock available in Berdyansk and Melitopol counties, instead demanding industrial goods in direct exchange for it.[18]

Governing bodies and attitude to government[]

| Part of a series on |

| Anarcho-communism |

|---|

|

|

To resolve issues relating to the territory as a whole, regional congresses of peasants, workers and rebels were convened. In total, during the period of the free existence of Makhnovia three such congresses were held.

At the first district congress, held on 23 January 1919, in the village of Mikhailovka, the main attention of the participants was drawn to the danger of Petliurism and Denikinism. To combat Petliurism, the congress decided to launch propaganda work in areas controlled by the directory in order to explain the essence of its policy to the population, to call for disobedience and boycott of the announced mobilization and for the continuation of the uprising in order to overthrow this power.[17]

The second district congress of peasants, workers and insurgents, which was attended by 245 delegates from 350 volosts and partisan detachments, gathered on 12 February in the village. The congress comprehensively discussed the question of the danger looming from Denikin. It was decided to immediately take measures to strengthen self-defense. The Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine, according to Peter Arshinov, had about 20 thousand volunteer fighters in their ranks by this time, many of whom, however, were "extremely overworked and frayed", participating in continuous battles of five to six months. In view of this, a decision was made to organize voluntary mobilization. Despite the large number of people who wanted to join Makhno, there were not enough weapons in the area to form new rebel units in time.[17]

The congress adopted a resolution expressing an anarchist negative attitude towards all state power, including the Soviet one:

"The Soviet government of Russia and Ukraine by its orders and decrees seeks at all costs to take away the freedom and independence of local Soviets of workers and peasants' deputies. Unelected committees, appointed by the government, oversee every step of the local Soviets and mercilessly crack down on those comrades from peasants and workers councils who defend their popular freedom against the representatives of the central government. The government of Russia and Ukraine, which calls itself a government of workers and peasants, blindly follows the party of the Bolshevik Communists, who, in the narrow interests of their party, are conducting the vile irreconcilable persecution of other revolutionary organizations. Hiding behind the slogan of the "dictatorship of the proletariat", the Bolshevik Communists declared a monopoly on revolution for their party, considering all dissenters to be counter-revolutionaries... We urge our worker and peasant comrades not to entrust the liberation of the workers to any party or central authority: the liberation of the workers is the work of the working people themselves..."[18][19]

For the general management of the struggle against the Petliurites and Denikinists, the implementation of congress decisions, as well as the organization of communication and propaganda work with the population, at the second congress, the Regional Military Revolutionary Council (MRC) of peasants, workers and rebels was formed. It included representatives of 32 volosts of Yekaterinoslav and Tauride provinces, as well as representatives of the rebel units. The MRC was in charge of all matters of a socio-political and military nature and represented the highest executive body of the Makhnovist movement.[17]

The main issues addressed by the MRC were the military, food, and local self-government. The solution to the issue of providing food to the entire population of the region was postponed until the fourth district congress, scheduled for 15 June 1919, which was prohibited by the Soviet government. The local peasantry took over the maintenance of the Black Army. In Huliaipole, the central army supply department organized the delivery of food and ammo to the front line.[17]

On 19 April the Makhnovist headquarters, defying the Red command's prohibition, convened the Third Huliaipole District Congress, which was attended by representatives of 72 volosts of the Aleksandrovsky, Mariupol, Berdyansk and Pavlograd districts of the Ekaterinoslav and Tauride provinces, as well as delegates from the Makhnovist military units. The congress proclaimed an anarchist platform, demanding "the immediate removal of all people appointed to military and civilian posts, the beginning of free and fair elections to these posts, the socialization of land and factories, the replacement of the policy of food requisitioning with a proper exchange system between city and country, full freedom of speech, press and assembly to all political leftist movements, inviolability of the workers of the left revolutionary organizations and the working people in general... We categorically do not recognize the dictatorship of any party".[18]

The so-called "Free Labor Councils of Peasants and Workers", fulfilling the will of local workers and their organizations, established the necessary connections among themselves, forming the highest bodies of public, social and economic self-government of the Makhnovist movement. The organization of such councils was never carried out in connection with the military situation. The general principles of the Free Council of Peasants and Workers were printed for the first time in 1920.[17]

Anarchism and the ideas of social reorganization[]

Makhno, who called himself "an anarcho-communist of the Bakunin-Kropotkin school", addressing like-minded people in an early July 1918 letter, urged them:

"Together we will destroy the slave system in order to bring ourselves and our comrades onto the path of the new system. We organize it on the basis of a free society, the content of which will allow the entire population, not exploiting the labor of others, to build their entire social and social life in their own communities, completely freely and independently of the state and its officials, even the Reds... Long live our peasants' and workers' union! Long live our auxiliary forces – an selfless intelligentsia of labor! Long live the Ukrainian social revolution! Yours, Nestor Ivanovich.[20]

A number of guerrilla unit commanders who arose in the Huliaipole district, in the summer of 1918, were also supporters of anarchism. At the beginning of 1919, the influence of anarchism on the rebel army of Makhno continued to grow due to the constant influx of ideological supporters of anarchy. These people enjoyed special privileges with Makhno, held leading positions in the rebel movement, contributed to the development of the Bat'ko's views and behavior, and exalted him as a "people's leader", "a great anarchist", and "second Bakunin". Anarchist ideas predetermined the development of Makhnovism, which inevitably led it to conflict with Soviet power.[18] In February – March 1919, Makhno invited the anarchist Pyotr Arshinov, with whom he served prison time in the same cell of the Butyrka prison, to join the Ukrainian rebellion and organize an anarchist newspaper for the rebels and workers and peasants. Arshinov arrived in April in Huliaipole, was elected chairman of the cultural and educational department of the Military Revolutionary Council, and editor of the newspaper "The Way to Freedom"; since the spring of 1919 he became one of the main ideologists of the Makhnovist movement.

Conflict with the Soviet command[]

Bolshevik hostility to Makhno and his anarchist army increased after Red Army defections. While the Soviet authorities chose not to pay attention to the frankly anti-Bolshevik nature of the resolutions of the February regional congress of Soviets, when the front stabilized in April, the authorities headed for the liquidation of Makhnovia's special status.[19] In the Soviet press, the Makhnovist movement began to qualify as kulak, its slogans as counter-revolutionary, and its actions as harmful to the revolution. Arshinov in his memoirs accused the Soviet authorities of organizing a blockade of the district, during which all "revolutionary workers" were detained. Supply of the Black Army with shells and ammunition, according to him, decreased by five or six times.[17] The Bolshevik press was not only silent on the subject of Moscow's continued refusal to send arms to the Black Army, but also failed to credit the Ukrainian anarchists' continued willingness to ship food supplies to the hungry urban residents of Bolshevik-held cities.

After 19 April the executive committee of the MRC of the Huliaipole region [17] convened the third district congress, which proclaimed the anarchist platform and declared categorically non-recognition of the dictatorship of any party,[18] the division commander Pavel Dybenko announced: "Any congresses convened on behalf of the military revolutionary headquarters, which was dismissed in accordance with my order, are considered clearly counter-revolutionary, and the organizers of these will be subjected to the most repressive measures, up to and including their outlawing".[19]

The commander of the Soviet Red Army’s Ukrainian Front Vladimir Antonov-Ovseyenko, who personally arrived in Huliaipole on 29 April, attempted to settle the conflict. During the negotiations, Makhno made concessions – he condemned the harshest provisions of the congresses' resolution and promised to impede the election of the command staff. At the same time, Makhno put forward a fundamentally new idea of the long-term coexistence of various political movements within the same power system: "Before a decisive victory over the whites, a revolutionary front must be established, and he (Makhno) seeks to prevent strife between various elements of this revolutionary front." This idea, however, was not accepted by the Soviet leadership, and Lev Kamenev, the representative of the republic's defense council, again demanded the liquidation of the political organs of the movement and, above all, the MRC.[19]

A new reason for mutual distrust arose in connection with the rebellion of Ataman Grigoriev in Right-Bank Ukraine. On May 12 [17] Kamenev sent a telegram to Makhno, kept in a clearly incredulous tone: "The traitor Grigoriev betrayed the front. Not executing a combat order, he holstered his weapon. The decisive moment has come – either you will go with the workers and peasants throughout Russia, or open the front to the enemies. Oscillations have no place. Immediately inform me of the location of your troops and issue an appeal against Grigoryev. I will consider non-receipt of an answer as a declaration of war. I believe in honor of the revolutionaries – yours, Arshinov, Veretelnikov and others."[19]

The "Bat'ko" gave a rather ambiguous answer: "The honor and dignity of the revolutionary force us to remain faithful to the revolution and the people, and Grigoryev's feuds with the Bolsheviks over regional power cannot force us to leave the front." After the scouts sent by Makhno to the area of Gregoriev's rebellion were intercepted by the authorities, the Makhnovists' final determination of their attitude towards Grigoryev dragged on until the end of May.

In his appeal, "Who is Grigoryev?" Makhno questioned the rebels: "Brothers! Don't you hear in his words a grim call to the Jewish pogrom?! Don't you feel the desire of Ataman Grigoriev to break the living fraternal connection between the revolution of Ukraine and revolutionary Russia?" At the same time, Makhno blamed the events on the actions of the Bolshevik authorities:" We must say that the reasons that created the entire Grigoriev movement are not in Grigoriev himself... Anything that showed resistance, protest, and even independence were stifled by special committees... This created the climate of bitterness, protest, and a hostile mood towards the existing order. Grigoriev took advantage of this in his adventure... We demand that the Communist Party be held accountable for the Grigoriev movement ".[19]

Grigoriev openly disagreed with Makhno during negotiations at Sentovo on 27 July 1919. Grigoriev had been in contact with Denikin's emissaries, and was planning to join the White coalition. According to Peter Arshinov, Makhno and staff decided to execute Grigoriev. Chubenko, a member of Makhno's staff, accused Grigoriev of collaborating with Denikin and of inciting the pogroms.[21] The accounts of Gregoriev's execution differ, and ascribe the final shot either to Chubenko, Karetnik, Kouzmenko or Makhno.[21][22][23]

The Bolshevik government in Petrograd increasingly saw the Makhnovists as a threat to their power, both as an example and as a site of anarchist influence.[24] The Bolsheviks began their formal efforts to disempower Makhno on 4 June 1919 with Trotsky's Order No. 1824, which forbade electing a congress and attempted to discredit Makhno by stating: "The Makhno brigade has constantly retreated before the White Guards, owing to the incapacity, criminal tendencies, and the treachery of its leaders."[25]

The Bolsheviks restarted a propaganda campaign declaring Makhnovia to be a region of warlords, and eventually broke with it by launching surprise attacks on Makhnovist militias[26] despite the pre-existing alliance between the factions.[27]

The Bolshevik press alleged that leaders in the Makhnovist movement, rather than being democratically-elected, were appointed by Makhno's military clique or even Makhno himself. They also alleged that Makhno himself had refused to provide food for Soviet railwaymen and telegraph operators, that the "special section" of the Makhnovist constitution provided for secret executions and torture, that Makhno's forces had raided Red Army convoys for supplies, stolen an armored car from Bryansk when asked to repair it, and that the Nabat group was responsible for deadly acts of terrorism in Russian cities.[28]

Vladimir Lenin soon sent Lev Kamenev to Ukraine where he conducted a cordial interview with Makhno. After Kamenev's departure, Makhno claimed to have intercepted two Bolshevik messages, the first an order to the Red Army to attack the Makhnovists, the second ordering Makhno's assassination. Soon after the Fourth Congress, Trotsky sent an order to arrest every Nabat congress member. Pursued by White Army forces, Makhno and the Black Army responded by withdrawing further into the interior of Ukraine. In 1919, the Black Army suddenly turned eastwards in a full-scale offensive, surprising General Denikin's White forces and causing them to fall back. Within two weeks, Makhno and the Black Army had recaptured all of southern Ukraine.

When Makhno's troops were struck by a typhus epidemic, Trotsky resumed hostilities; the Cheka sent two agents to assassinate Makhno in 1920, but they were captured and, after confessing, were executed. All through February 1920 Makhnovia was inundated with 20,000 Red troops.[29] Viktor Belash noted that even in the worst time for the revolutionary army, namely at the beginning of 1920, "In the majority of cases rank-and-file Red Army soldiers were set free, in all four directions". This happened at the beginning of February 1920, when the insurgents disarmed the 10,000-strong Estonian Division in Huliaipole.[30] The problem was further compounded by the alienation of the Estonians by Denikin's inflexible Russian chauvinism and their refusal to fight with Nikolai Yudenich.[31]

There was a new truce between Makhnovist forces and the Red Army in October 1920 in the face of a new advance by Wrangel's White Army. While Makhno and the anarchists were willing to assist in ejecting Wrangel and White Army troops from southern Ukraine and Crimea, they distrusted the Bolshevist government in Moscow and its motives. However, after the Bolshevik government agreed to a pardon of all anarchist prisoners throughout Russia, a formal treaty of alliance was signed.

By late 1920, Makhno had halted General Wrangel's White Army advance into Ukraine from the southwest, capturing 4,000 prisoners and stores of munitions, and preventing the White Army from gaining control of the all-important Ukrainian grain harvest. To the end, Makhno and the anarchists maintained their main political structures, refusing demands to join the Red Army, to hold Bolshevik-supervised elections, or accept Bolshevik-appointed political commissars.[32] The Red Army temporarily accepted these conditions, but within a few days ceased to provide the Makhnovists with basic supplies, such as cereals and coal.

When General Wrangel's White Army forces were decisively defeated in November 1920, the Bolsheviks immediately turned on Makhno and the anarchists once again. On 26 November 1920, less than two weeks after assisting Red Army forces in defeating Wrangel, Makhno's headquarters staff and many of his subordinate commanders were arrested at a Red Army planning conference to which they had been invited by Moscow, and executed. Makhno escaped, but was soon forced into retreat as the full weight of the Red Army and the Cheka's "special punitive brigades" were brought to bear against not only the Makhnovists, but all anarchists, even their admirers and sympathizers.[33] In August 1921, after making raids all across Ukraine and constant battles with Red Army forces many times larger and better equipped an exhausted Makhno was finally driven by Mikhail Frunze's Red forces into exile with 77 of his men.

Politics[]

Makhnovia was a stateless and egalitarian society. Workers and peasants were organised into anarchist communities governed via a process of participatory democracy and were linked via an anarchist federation.[34]

When the Insurrectionary Army liberated a town from state control, it would post a notice clarifying that they would not impose any authority on the town:

Workers, your city is for the present occupied by the Revolutionary Insurrectionary (Makhnovist) Army. This army does not serve any political party, any power, any dictatorship. On the contrary, it seeks to free the region of all political power, of all dictatorship. It strives to protect the freedom of action, the free life of the workers, against all exploitation and domination. The Makhnovist Army does not, therefore, represent any authority. It will not subject anyone to any obligation whatsoever. Its role is confined to defending the freedom of the workers. The freedom of the peasants and the workers belong to themselves, and should not suffer any restriction.[34]

Economy[]

Makhnovia was an effort to create an anarcho-communist economy.

Agriculture[]

Peasants who lived in Makhnovia began to self-organise into farming communes. The first one, called "Rosa Luxemburg" was highly successful. In these communes, land was held in common, and kitchen and dining rooms were also communal, though members who wished to cook separately or to take food from the kitchen and eat it in their own quarters were allowed to do so. Though only a few members actually considered themselves anarchists, the peasants operated the communes on the basis of full equality ("from each according to his ability, to each according to his need") and accepted Kropotkin's principle of mutual aid as their fundamental tenet.[35]

Industry[]

Railroad workers in Aleksandrovsk took the first steps in organising a self-managed economy in 1919. They formed a committee charged with organizing the railway network of the region, establishing a detailed plan for the movement of trains, the transport of passengers, etc. Soviets were soon formed to coordinate factories and other enterprises across Ukraine.[36]

Art and entertainment[]

The Makhnovists paid a great amount of attention to theatre, and soldiers from the Black Army often practiced theatre to entertain themselves and keep up morale. In Huliaipole, many workers and students began to write and perform in plays.[37]

Money[]

The economy of Free Ukraine was a mixture of anarcho-communism and market socialism, with factories, farms and railways becoming cooperatives and many moneyless communities being created. The majority of territories continued to use money but planned to become anarcho-communist territories following the Russian Civil War.[34] In 1920, the Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army declared that all types of money must be accepted within the territories, threatening "revolutionary punishment" to those who failed to follow this.[38]

Education[]

As a result of the war, schools were abandoned and teachers received no wages, meaning education was nonexistent in the region for months. Upon the creation of soviets and assemblies in the region, the reconstruction of schools began. Inspired by the free schools of Ferrer, the soviets set up some of the first secular and democratic schools in Ukraine, having abolished compulsory education. Courses were set up for illiterate and semi-literate adults to help them read and courses for history, sociology and political theory were all offered free of charge to the general public.[37] All of these efforts increased literacy in the region.[39]

Flags[]

Multiple variations of the black and red flags were used by the Makhnovists during the Russian Civil War. These banners were inscribed either with anarchist and socialist slogans or with the name of the unit using the flag.[40] Ukrainian anarchist Viktor Belash said in his memoirs that flags with slogans such as "Power generates parasites, Long live Anarchy!" and "All power to the soviets right now!" were used at the Gulyai-Polye district soviet and Insurgent Army headquarters.[2] A photo showing a flag with a death's head and the motto "Death to all those who stand in the way of the working people." is often falsely attributed to Makhnovists, first in the Soviet Russian book Jewish Pogroms 1917–1921 by Z.S. Ostrovsky,[41] but this was denied by Nestor Makhno, who said the photo "does not show Makhnovists at all".[42] The reverse side of this flag has words translating roughly to "Kish of the Dnieper".[40] The word Kish, meaning a Cossack camp, at this time was used by the Ukrainian People's Republic to refer to battalions of the Ukrainian People's Army.[43]

Makhnovist flag, proclaiming "Death to all those who stand in the way of the working people"

One of the flags described by Viktor Belash

Flag used by the 2nd Insurgent Regiment of the RIAU

Obverse of the banner attributed to the Makhnovists by Ostrovsky

Reverse of the banner attributed to the Makhnovists by Ostrovsky

Human rights[]

Makhnovia lifted all restrictions on the press, speech, assembly and political organisations. Six new newspapers formed, among them the right socialist-revolutionary Narodovlastie (The People's Power), the left socialist-revolutionary Znamya Vosstanya (), and the Bolshevik Zvezda ().[44]

See also[]

- Armed Forces of South Russia

- Revolutionary Catalonia

- Shinmin Autonomous Zone

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Noel-Schwartz, Heather.The Makhnovists & The Russian Revolution – Organization, Peasantry and Anarchism. Archived on Internet Archive. Accessed October 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Skirda 2004, p. 86.

- ^ Peter Marshall, Demanding the Impossible, PM Press (2010), p. 473.

- ^ Malet 1982, p. 19.

- ^ Skirda 2004, p. 34.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Edward R. Kantowicz (1999). The Rage of Nations. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-8028-4455-2.

- ^ Magocsi 1996, p. 499.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Magocsi 1996, pp. 498–99; Subtelny 1988, p. 360.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Komin V.V. Nestor Makhno. Myths and reality. Chapter "The birth of the father." M., 1990

- ^ Jump up to: a b Declaration Of The Revolutionary Insurgent Army Of The Ukraine (Makhnovist). Peter Arshinov, History of the Makhnovist Movement (1918–1921), 1923. Black & Red, 1974

- ^ Simon Pirani, The Russian Revolution in Retreat, 1920–24: Soviet Workers and the New Communist Elite, Routledge, 2008, p. 96.

- ^ Nestor Makhno—anarchy's Cossack

- ^ Declaration Of The Revolutionary Insurgent Army Of The Ukraine (Makhnovist). Peter Arshinov, History of the Makhnovist Movement (1918–1921), 1923. Black & Red, 1974

- ^ Avrich, Paul. Anarchist Portraits, 1988, Princeton University Press, pp. 114, 121.

- ^ Schwartz, Heather-Noël (January 7, 1920), The Makhnovists & The Russian Revolution: Organization, Peasantry, and Anarchism, archived from the original on January 18, 2008, retrieved January 18, 2008

- ^ Footman, David. Civil War In Russia Frederick A.Praeger 1961, page 287

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k The Fall of the Hetman. Petliurism. Bolshevism.. Peter Arshinov, History of the Makhnovist Movement (1918–1921), 1923. Black & Red, 1974

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Komin V.V. Nestor Makhno. Myths and reality. Chapter “Walk the Field”. – M., 1990.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Shubin A.V. The Makhnovist movement: the tragedy of the 19th// Community, 1989, No. 34.

- ^ Komin V.V. Nestor Makhno. Myths and reality. Ch. "At the crossroads". – M .: Moscow Worker, 1990. – ISBN 5-239-00858-2

- ^ Jump up to: a b Skirda 2004, p. 125.

- ^ Nestor Makhno, "The Makhnovshchina and Anti-Semitism," Dyelo Truda, No.30-31, November–December 1927, pp.15–18

- ^ Peter Arshinov "History of the Makhnovist Movement 1918–1921" Ch. 7

- ^ Skirda 2004, p. 236.

- ^ Daniel Cohn-Bendit and Gabriel Cohn-Bendit, The Makhno Movement and Opposition Within the Party

- ^ Skirda 2004, p. 238.

- ^ Skirda 2004, p. 237.

- ^ Yanowitz, Jason (2007). "International Socialist Review". www.isreview.org. Retrieved 2019-09-29.

- ^ , An Unsolved Mystery – The "Diary of Makhno's Wife".

- ^ , "The Red Army on the Internal Front", Gosizdat (1927), p. 52.

- ^ Why did the Bolsheviks win the Russian Civil War? compares the tactics and resources of the two sides.

- ^ NESTOR MAKHNO Ukrainian anarchist general, fought both Reds & Whites (tyranny left to right). Archived 2008-06-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Voline, The Unknown Revolution, pp. 693–97: Anyone in Ukraine who professed anarchist sympathies was marked for retribution. Voline recounts the example of M. Bogush, a Russian-born anarchist who had emigrated to America. He returned to Russia in 1921 after being expelled from the United States. Having heard a great deal about Makhno and the Ukrainian anarchists, he left Kharkiv to see Makhno's birthplace at Huliaipole. After only a few hours, he returned to Kharkiv, where he was arrested by the order of the Cheka, and was shot in March 1921.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Eikhenbaum, Vsevolod (1947). The Unknown Revolution, 1917 – 1921. Book Three. The Struggle For Real Social Revolution.

- ^ Voline (1947). The Unknown Revolution: 1917 – 1921, Book III, the struggle for real social revolution, Part II: Ukraine (1918–1921).

- ^ Arshinov, Peter (1923). History of the Makhnovist Movement. p. 84.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Arshinov, Peter (1923). History of the Makhnovist Movement. pp. 102–103.

- ^ MILITARY REVOLUTIONARY COUNCIL AND COMMAND STAFF OF THE REVOLUTIONARY INSURGENT ARMY OF THE UKRAINE (MAKHNOVISTS) (7 January 1920). "To All Peasants and Workers of the Ukraine". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ^ Gelderloos, Peter (2010). Anarchy Works.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Флаги гражданской войны. Армия Н.Махно". Vexillographia. Russian Centre of Vexillology and Heraldry. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ Ostrovsky, Z.S. (1926). Jewish Pogroms 1917–1921. Акц. p. 100. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ Makhno, Nestor (April–May 1927). "To the Jews of all Countries". Delo Truda. Libcom.org: 8–10. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

By contrast, the same document does mention a number of pogroms and alongside prints the photographs of Makhnovist insurgents, though it is not clear what they are doing there, on the one hand, and which, in point of fact are no even Makhnovists, as witness the photograph purporting to show 'Makhnovists on the move' behind a black flag displaying a death's head: this is a photo that has no connection with pogroms and indeed and especially does not show Makhnovists at all.

- ^ Gilley, Christopher (1 February 2017). "Fighters for Ukrainian independence? Imposture and identity among Ukrainian warlords, 1917–22". Historical Research. 90 (247): 172–190. doi:10.1111/1468-2281.12168.

- ^ Arshinov, Peter (1923). History of the Makhnovist Movement. p. 87.

Bibliography[]

- Arshinov, Peter (1974) [1923]. History of the Makhnovist Movement. Detroit: Black & Red. OCLC 579425248.

- Darch, Colin (2020). Nestor Makhno and Rural Anarchism in Ukraine, 1917–21. London: Pluto Press. ISBN 0745338887. OCLC 1225942343.

- Eichenbaum, Vsevolod Mikhailovich (1955) [1947]. The Unknown Revolution. Translated by Cantine, Holley. New York: Libertarian Book Club. ISBN 0919618251. OCLC 792898216.

- Makhno, Nestor (2009). Skirda, Alexandre (ed.). Mémoires et écrits: 1917-1932 (in French). Paris: Ivrea. ISBN 9782851842862. OCLC 690866794.

- Makhno, Nestor (2007) [1928]. The Russian Revolution in Ukraine (March 1917 - April 1918). Translated by Archibald, Malcolm. Edmonton: Black Cat Press. ISBN 9780973782714. OCLC 187835001.

- Makhno, Nestor (1996). Skirda, Alexandre (ed.). The Struggle Against the State and Other Essays. Translated by Sharkey, Paul. Edinburgh: AK Press. ISBN 1873176783. OCLC 924883878.

- Malet, Michael (1982). Nestor Makhno in the Russian Civil War. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-25969-6. OCLC 1194667963.

- Palij, Michael (1976). The Anarchism of Nestor Makhno, 1918–1921. Publications on Russia and Eastern Europe of the Institute for Comparative and Foreign Area Studies. 7. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295955112. OCLC 2372742.

- Shubin, Aleksandr (2010). "The Makhnovist Movement and the National Question in the Ukraine, 1917–1921". In Hirsch, Steven J.; van der Walt, Lucien (eds.). Anarchism and Syndicalism in the Colonial and Postcolonial World, 1870–1940. Studies in Global Social History. 6. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004188495. OCLC 868808983.

- Skirda, Alexandre (2004) [1982]. Nestor Makhno: Anarchy's Cossack. Translated by Sharkey, Paul. Edinburgh: AK Press. ISBN 1-902593-68-5. OCLC 58872511.

Coordinates: 47°46′8″N 36°44′28″E / 47.76889°N 36.74111°E

- Anarchist communities

- Anarchist revolutions

- Makhnovism

- Russian Revolution in Ukraine

- Post–Russian Empire states

- Anarchism in Ukraine

- History of Zaporizhzhia Oblast

- History of Donetsk Oblast

- History of Dnipropetrovsk Oblast

- 1918 establishments in Ukraine

- 1921 disestablishments in Ukraine

- States and territories established in 1918

- States and territories disestablished in 1921

- 20th-century revolutions

- Former polities of the interwar period

- Former countries