Methasterone

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Superdrol; Methyldrostanolone; Methasteron; 2α,17α-Dimethyl-4,5α-dihydrotestosterone; 2α,17α-Dimethyl-DHT; 2α,17α-Dimethyl-5α-androstan-17β-ol-3-one |

| Routes of administration | oral |

| Drug class | Androgen; Anabolic steroid |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ~50%[citation needed] |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 8–12 hours |

| Excretion | Urine |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H34O2 |

| Molar mass | 318.501 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

show

SMILES | |

show

InChI | |

| | |

Methasterone, also known as methyldrostanolone and known by the nickname Superdrol, is a synthetic and orally active anabolic–androgenic steroid (AAS) which was never marketed for medical use. It was brought to the black market, instead, in a clandestine fashion as a "designer steroid."

Medical uses[]

Methasterone was never a commercially available prescription drug. Its non-17α-alkylated counterpart, drostanolone propionate, was commercialized by Syntex Corporation under the brand name Masteron.[1]

Non-medical uses[]

Methasterone resurfaced in 2005 as a “designer steroid”.[2] It was brought to market by Designer Supplements as the primary ingredient of a dietary supplement named Superdrol. Its introduction into commerce may have represented an attempted circumvention of the U.S. Anabolic Steroids Control Act of 1990 (along with its 2004 revision), since the law is, in part, drug-specific;[3] methasterone, as is the case with many designer steroids, was not declared a Schedule III class anabolic steroid in that act because it was not commercially available at the time the act, and its subsequent revision, were signed into law.[4] Methasterone was therefore being sold as an over-the-counter dietary supplement.

Side effects[]

Methasterone is hepatotoxic (toxic to the liver). Several cases of liver damage due to the use of methasterone have been cited in the medical literature.[5][6][7][8]

Chemistry[]

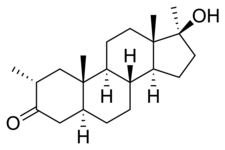

Methasterone, also known as 2α,17α-dimethyl-5α-dihydrotestosterone (2α,17α-dimethyl-DHT) or as 2α,17α-dimethyl-5α-androstan-17β-ol-3-one, is a synthetic androstane steroid and a 17α-alkylated derivative of DHT.

Mebolazine is formed by hydrazone formation between two equivalents of methasterone with one equivalent of hydrazine.

History[]

The synthesis of methasterone is first mentioned in the literature in 1956 in connection with research conducted by Syntex Corporation in order to discover a compound with anti-tumor properties.[9] In a 1959 research journal article, it is initially mentioned and is elaborated upon where its method of synthesis is discussed in greater detail, its tumor inhibiting properties are verified, and it is noted as being a “potent orally active anabolic agent exhibiting only weak androgenic activity.”[10] The results of subsequent assays to determine methasterone's anabolic and androgenic activity were published in Vida's Androgens and Anabolic Agents, a dated but still standard reference, where it was noted that methasterone possessed the oral bioavailability of methyltestosterone while being 400% as anabolic and 20% as androgenic, yielding a Q-ratio (anabolic to androgenic ratio) of 20, which is considered very high.[11]

Designer steroid[]

It was in late 2005 that the reclassification of methasterone as AAS (as well as that of four other designer steroids) was brought to public awareness via an article published in the Washington Post.[12] Don Catlin of the UCLA Olympic Laboratory, who conducted the studies, noted methasterone's similarity to drostanolone. A warning by the FDA was issued soon after to the general public as well as to the distributor, Designer Supplements LLC, for the marketing of this compound.[13] Methasterone was subsequently added to the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) list of prohibited substances in sport.[14] Despite all of this, methasterone has resurfaced within the supplement industry on several occasions since its banning by WADA.[15]

References[]

- ^ "Superdrol, masteron en oxy komen uit hetzelfde nest" [Superdrol, Masteron, and Oxy come from the same nest]". Ergogenics.org. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ Peter Van Enoo & Frans T. Delbeke (2006). "Metabolism and excretion of anabolic steroids in doping control—New steroids and new insights". Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 101 (4–5): 161–78. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.06.024. PMID 17000101. S2CID 33621513.

- ^ "Implementation of the Anabolic Steroid Control Act of 2004". Office of Divesion Control, Drug Enforcement Administration, Department of Justice. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ Amy Shipley; Bonnie Berkowitz & Christina Rivero (October 18, 2005). "Designer Steroids Hide and Seek". The Washington Post. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ Beata Jasiurkowski, Jaya Raj, David Wisinger, Richard Carlson, Lixian Zou, and Abdul Nadir (2006). "Cholestatic Jaundice and IgA Nephropathy Induced by OTC Muscle Building Agent Superdrol". American Journal of Gastroenterology. 101 (11): 2659–2662. PMID 16952289.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ John Nasr & Jawad Ahmad (2008). "Severe Cholestasis and Renal Failure Associated with the Use of the Designer Steroid Superdrol (Methasteron): A Case Report and Literature Review". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 10: 1007.

- ^ Neeral L. Shah, Isabel Zacharias, Urmila Khettry, Nezam Afdhal, and Fredric D. Gordon (2008). "Methasteron-Associated Cholestatic Liver Injury: Clinicopathologic Findings in 5 Cases". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 6 (2): 255–258. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2007.11.010. PMID 18187367.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ Singh V, Rudraraju M, Carey EJ, Byrne TJ, Vargas HE, Williams JE, Balan V, Douglas DD, Rakela J (March 2009). "Severe Hepatotoxicity Caused by a Methasteron-containing, Performance-enhancing Supplement". Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 43 (3): 287. doi:10.1097/mcg.0b013e31815a5796. PMID 18813027.

- ^ H. J. Ringold & G. Rosenkranz (1956). "Steroids. LXXXIII. Synthesis of 2-Methyl and 2,2-Dimethyl Hormone Analogs". Journal of Organic Chemistry. 21: 1333–1335. doi:10.1021/jo01117a625.

- ^ H. J. Ringold, E. Batres, O. Halpern, and E. Necoechea (1959). "Steroids. CV.1 2-Methyl and 2-Hydroxymethylene-androstane Derivatives". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 81 (2): 427–432. doi:10.1021/ja01511a040.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ Julius A. Vida (1969). Androgens and Anabolic Agents: Chemistry and Pharmacology. New York: Academic Press. pp. 23 & 168.

- ^ Amy Shipley (November 30, 2005). "Steroids Detected in Dietary Tablets". The Washington Post. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ "FDA Warns Manufacturers About Illegal Steroid Products Sold as Dietary Supplements". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. March 9, 2006. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ "The World Anti-Doping Code: The 2009 Prohibited List: International Standard" (PDF). World Anti-Doping Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-03. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ David Epstein; George Dohrmann (May 18, 2009). "What You Don't Know Might Kill You: Would-be experts and untested products feed a $20 billion obsession with better performance across all levels of sports". Sports Illustrated.

- Drugs not assigned an ATC code

- Abandoned drugs

- Androgens and anabolic steroids

- Androstanes

- Designer drugs

- Hepatotoxins

- World Anti-Doping Agency prohibited substances