Minidoka National Historic Site

| Minidoka National Historic Site | |

|---|---|

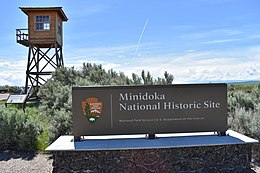

Entrance and guard tower in 2019 | |

Minidoka NHS Location in Idaho | |

| Location | Jerome County, Idaho, U.S. |

| Nearest city | Eden |

| Coordinates | 42°40′44″N 114°14′38″W / 42.679°N 114.244°WCoordinates: 42°40′44″N 114°14′38″W / 42.679°N 114.244°W |

| Area | 210 acres (85 ha)[1] |

| Authorized | January 17, 2001[2] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Minidoka National Historic Site |

NHS

Minidoka National Historic Site is a National Historic Site in the western United States. It commemorates the more than 9,000 Japanese Americans who were imprisoned at the Minidoka War Relocation Center during the Second World War.[3]

Located in the Magic Valley of south central Idaho in Jerome County, the site is in the Snake River Plain, a remote high desert area north of the Snake River. It is 17 miles (27 km) northeast of Twin Falls and just north of Eden, in an area known as Hunt. The site is administered by the National Park Service of the U.S. Department of the Interior, and was originally established as the Minidoka Internment National Monument in 2001.[2] Its elevation is just under 4,000 feet (1,220 m) above sea level.

Minidoka War Relocation Center[]

The Minidoka War Relocation Center operated from 1942 to 1945 as one of ten camps at which Japanese Americans, both citizens and resident "aliens", were interned during World War II. Under provisions of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Executive Order 9066, all persons of Japanese ancestry were excluded from the West Coast of the United States. At its peak, Minidoka housed 9,397 Japanese Americans, predominantly from Oregon, Washington, and Alaska.[3][4]

The Minidoka irrigation project shares its name with Minidoka County. The Minidoka name was applied to the Idaho relocation center in Jerome County, probably to avoid confusion with the Jerome War Relocation Center in Jerome, Arkansas.[citation needed] Construction by the Morrison-Knudsen Company began in 1942 on the camp, which received 10,000 internees by years' end. Many of the internees worked as farm labor, and later on the irrigation project and the construction of Anderson Ranch Dam, northeast of Mountain Home. The Reclamation Act of 1902 had racial exclusions on labor which were strictly adhered to until Congress changed the law in 1943.[5] Population at the Minidoka camp declined to 8,500 at the end of 1943, and to 6,950 by the end of 1944. The camp formally closed on October 28, 1945.[6] On February 10, 1946, the vacated camp was turned over to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, which used the facilities to house returning war veterans.[7]

The Minidoka War Relocation Center consisted of 36 blocks of housing. Each block contained 12 barracks (which themselves were divided into 6 separate living areas), laundry facilities, bathrooms, and a mess hall. Recreation Halls in each block were multi-use facilities that served as both worship and education centers. Minidoka had a high school, a junior high school and two elementary schools - Huntsville and Stafford.[8] The Minidoka War Relocation Center also included two dry cleaners, four general stores, a beauty shop, two barber shops, radio and watch repair stores as well as two fire stations.[9]

In June 1942, the War Department authorized the formation of the 100th Infantry Battalion consisting of 1,432 men of Japanese descent in the Hawaii National Guard and sent them to Camps McCoy and Shelby for advanced training.[10] Because of its superior training record, FDR authorized the formation of the 442nd RCT in January 1943 when 10,000 men from Hawaii signed up with eventually 2,686 being chosen along with 1,500 from the mainland.[11] The Minidoka Internees created an Honor Roll display to acknowledge the service of their fellow Japanese-Americans.[8] According to Echoes of Silence,[12] 844 men from this camp volunteered or were drafted for military service.[13] Although the original was lost after the war, the Honor Roll was recreated by the Friends of Minidoka group in 2011 following a grant from the National Park Service.[14]

Terminology[]

Since the end of World War II, there has been debate over the terminology used to refer to Minidoka, and the other camps in which Americans of Japanese ancestry and their immigrant parents, were incarcerated by the United States Government during the war.[15][16][17] Minidoka has been referred to as a "War Relocation Center", "relocation camp", "relocation center", "internment camp", and "concentration camp", and the controversy over which term is the most accurate and appropriate continues to the present day.[18][19][20]

National Historic Site[]

at the Minidoka War Relocation Center

The internment camp site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on July 10, 1979. A national monument was established in 2001 at the site by President Bill Clinton on January 17, as he invoked his authority under the Antiquities Act.[2] As one of the newer units of the National Park System, it currently has temporary visitor facilities and services available on location. A new visitor contact station is being built and will open in 2020. Currently, visitors see the remains of the entry guard station, waiting room, and rock garden and can visit the Relocation Center display at the in nearby Jerome and the restored barracks building at the southeast of town. There is a small marker adjacent to the remains of the guard station, and a larger sign at the intersection of Highway 25 and Hunt Road, which gives some of the history of the camp.

The National Park Service began a three-year public planning process in the fall of 2002 to develop a General Management Plan (GMP) and Environmental Impact Statement (EIS).[citation needed] The General Management Plan sets forth the basic management philosophy for the Monument and provides the strategies for addressing issues and achieving identified management objectives that will guide management of the site for the next 15–20 years.[citation needed]

In 2006, President George W. Bush signed H.R. 1492 into law on December 21, guaranteeing $38 million in federal money to restore the Minidoka relocation center along with nine other former Japanese internment camps.[21]

Less than two years later on May 8, 2008, President Bush signed the Wild Sky Wilderness Act into law, which changed the status of the former U.S. National Monument to National Historic Site and added the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial on Bainbridge Island, Washington to the monument.[22][23]

Notable Minidoka incarcerees[]

- Paul Chihara (born 1938), an American composer.

- Ken Eto (1919–2004), a Japanese American mobster with the Chicago Outfit and eventually an FBI informant.

- Fumiko Hayashida (1911–2014), an American activist. Also interned at Manzanar.

- Shizue Iwatsuki (1897–1984), a Japanese American poet. Also interned at Tule Lake.

- Taky Kimura (1924–2021), a martial arts practitioner and instructor. Also interned at Tule Lake.

- Joseph Kitagawa (1915–1992), professor at the University of Chicago, known for his work in the history of religions

- Fujitaro Kubota (1879–1973), an American gardener and philanthropist.

- Frank Kunishige (1878–1960), a well-known pictorialist photographer, and a founder of the Seattle Camera Club. Also detained at Camp Harmony.

- Aki Kurose (1925–1998), a Seattle teacher and civil rights activist.

- Dr Kyo Koike (1878–1947), a respected surgeon and poet, who also was a noted photographer and a founder of the Seattle Camera Club.

- John Matsudaira (1922–2007), an American painter.

- Mich Matsudaira (1937–2019), an American businessman and civil rights activist.

- Shig Murao (1926–1999), a San Francisco clerk who played a prominent role in the San Francisco Beat scene.

- William K. Nakamura (1922–1944), a United States Army soldier and a recipient of the Medal of Honor.

- George Nakashima (1905–1990), a Japanese American woodworker, architect, and furniture maker.

- Mira Nakashima (1942), an architect and furniture maker.

- Kenjiro Nomura (1896–1956), a Japanese-American painter.

- Frank Okada (1931–2000), an American Abstract Expressionist painter.

- John Okada (1923–1971), a Japanese American writer.

- James Sakamoto (1903–1955), a journalist, boxer and community organizer.

- Bell M. Shimada (1922–1958), an American fisheries scientist.

- Roger Shimomura (born 1939), an American artist and Professor of Art (ret).

- Monica Sone (1919–2011), a Japanese American novelist.

- Gary A. Tanaka (born 1943), a Japanese American businessman.

- Kamekichi Tokita (1897–1948), a Japanese American painter and diarist.

- Herbert T. Ueda (1929–2020), an American ice drilling engineer.

- Newton K. Wesley (1917–2011), an optometrist and an early pioneer of the contact lens[24]

- Kenji Yamada (1924-2014), a two-time U.S. National Judo champion

- Mitsuye Yamada (born 1923), a Japanese American writer.

- Takuji Yamashita (1874–1959), an early 20th-century civil rights pioneer. Also interned at Tule Lake and Manzanar.

- Minoru Yasui (1916–1986), a Japanese American lawyer who challenged the constitutionality of curfews used during World War II in Yasui v. United States.

See also[]

- National Parks in Idaho

- Kooskia Internment Camp

- Tule Lake Unit, World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument

- Manzanar National Historic Site

- Minidoka Irrigator (Minidoka internment camp newspaper)

- War Relocation Authority

- Other camps:

- Gila River War Relocation Center

- Granada War Relocation Center

- Heart Mountain War Relocation Center

- Jerome War Relocation Center

- Poston War Relocation Center

- Rohwer War Relocation Center

- Topaz War Relocation Center

References[]

- ^ "Listing of acreage as of December 31, 2011" (PDF). Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-12-14.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c

Proclamation 7395 - Establishment of the Minidoka Internment National Monument. by President Bill Clinton

Proclamation 7395 - Establishment of the Minidoka Internment National Monument. by President Bill Clinton

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Minidoka," Archived 2017-03-19 at the Wayback Machine Hanako Wakatsuki. Densho Encyclopedia, 10 June 2013.

- ^ "Friends of Minidoka: Japanese American Internment during World War II". Archived from the original on 2014-11-11. Retrieved 2014-04-22.

- ^ National Park Service Archived 2012-04-15 at the Wayback Machine - history - Anderson Ranch Dam & Powerplant, Idaho - accessed 2012-02-09

- ^ "Idaho: Minidoka Internment National Historic Site". www.nps.gov. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2019-10-20. Retrieved 2019-10-20.

- ^ Stene, Eric A. (1997). "The Minidoka Project" (PDF). U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-05.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-04-15. Retrieved 2013-03-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-02-23. Retrieved 2013-03-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-09-09. Retrieved 2019-11-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2019-12-20. Retrieved 2019-11-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Japanese American Living Legacy - A California Non-Profit Organization". Archived from the original on 2016-03-31. Retrieved 2019-11-23.

- ^ "Dropbox - Error".

- ^ "Rebuilding the Honor Roll at Minidoka". Friends or Minidoka. Archived from the original on March 30, 2015. Retrieved August 24, 2014.

- ^ "The Manzanar Controversy". Public Broadcasting System. Archived from the original on June 5, 2012. Retrieved July 18, 2007.

- ^ Daniels, Roger (May 2002). "Incarceration of the Japanese Americans: A Sixty-Year Perspective". The History Teacher. 35 (3): 4–6. doi:10.2307/3054440. JSTOR 3054440. Archived from the original on December 29, 2002. Retrieved July 18, 2007.

- ^ Ito, Robert (September 15, 1998). "Concentration Camp Or Summer Camp?". Mother Jones. Archived from the original on January 4, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- ^ Reflections: Three Self-Guided Tours Of Manzanar. Manzanar Committee. 1998. pp. iii–iv.

- ^ "CLPEF Resolution Regarding Terminology". Civil Liberties Public Education Fund. 1996. Archived from the original on July 3, 2007. Retrieved July 20, 2007.

- ^ "Densho: Terminology & Glossary: A Note On Terminology". Densho. 1997. Archived from the original on June 24, 2007. Retrieved July 15, 2007.

- ^ "H.R. 1492". georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-09-26. Retrieved 2017-09-05.

- ^ Pacific Citizen Staff, Associated Press (2008-05-16). "Bush Signs Bill Expanding Borders of Minidoka Monument". Japanese American Citizens League. Archived from the original on August 30, 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- ^ Stahl, Greg (2008-05-14). "Congress Expands Minidoka Site". Idaho Mountain Express. Archived from the original on 2008-05-21. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- ^ "Newton K. Wesley: 1917-2011 Eye care pioneer helped evolve contact lenses". Chicago Tribune. 25 July 2011. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Minidoka National Historic Site. |

- Japanese Relocation (1943 FILM- viewable for free at not-for profit- The Internet Archive)

- Official Park Service site

- Wakatsuki, Hanako. "Densho Encyclopedia: Minidoka". encyclopedia.densho.org. Densho. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

- Wakida, Patricia. "Densho Encyclopedia: Minidoka Irrigator (newspaper)". encyclopedia.densho.org. Densho. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

- Minidoka Relocation Center historical photographs at the University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections

- Paintings of Minidoka by Ed Tsutakawa

- Arthur Kleinkopf diary, MSS 1736 at L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University. Contains information about internee's daily life at the Minidoka relocation camp.

- 2001 establishments in Idaho

- Buildings and structures in Jerome County, Idaho

- Internment camps for Japanese Americans

- National Historic Sites in Idaho

- Protected areas established in 2001

- Protected areas of Jerome County, Idaho

- Residential buildings on the National Register of Historic Places in Idaho

- Tourist attractions in Jerome County, Idaho

- National Register of Historic Places in Jerome County, Idaho

- Temporary populated places on the National Register of Historic Places