Blue Origin

Feather logo | |

| Type | Limited liability company |

|---|---|

| Industry | Aerospace |

| Founded | September 8, 2000 |

| Founder | Jeff Bezos |

| Headquarters | Kent, Washington , U.S. |

Key people | Bob Smith (CEO)[1] |

| Owner | Jeff Bezos |

Number of employees | 3,500[2][3] (2021) |

| Website | BlueOrigin.com |

| Part of a series on |

| Private spaceflight |

|---|

| Active companies |

|

| Active vehicles |

|

| Contracts and programs |

|

|

Blue Origin, LLC is an American privately funded aerospace manufacturer and sub-orbital spaceflight services company headquartered in Kent, Washington.[4][5] Founded in 2000 by Jeff Bezos, the founder and executive chairman of Amazon, the company is led by CEO Bob Smith and aims to make access to space cheaper and more reliable through reusable launch vehicles.[6][7] Rob Meyerson led Blue Origin from 2003 to 2017 and served as its first president.[8] Blue Origin is employing an incremental approach from suborbital to orbital flight,[citation needed] with each developmental step building on its prior work.[9] The company's name refers to the blue planet, Earth, as the point of origin.[10]

Blue Origin develops orbital technology, rocket-powered vertical takeoff and vertical landing (VTVL) vehicles for access to suborbital and orbital space.[11] Initially focused on suborbital spaceflight, the company has designed, built and flown multiple testbeds of its New Shepard vehicle at its facilities in Culberson County, Texas. Developmental test flights of the New Shepard,[12] named after the first American in space Alan Shepard, began in April 2015, and flight testing is ongoing.[13][14] Blue Origin rescheduled the original 2018 date for first passengers several times, and eventually successfully flew its first crewed mission on July 20, 2021.[15] It has not yet begun commercial passenger flights, nor announced a firm date for when they would begin. On nearly every one of the test flights since 2015, the unmanned vehicle has reached a test altitude of more than 100 kilometers (330,000 ft) and achieved a top speed of more than Mach 3, reaching space above the Kármán line, with both the space capsule and its rocket booster successfully soft landing.[16]

Blue Origin moved into the orbital spaceflight technology development business in 2014, initially as a rocket engine supplier for others via a contractual agreement to build a new large rocket engine, the BE-4, for major US launch system operator United Launch Alliance (ULA). Blue said the "BE-4 would be 'ready for flight' by 2017."[17] By 2015, Blue Origin had announced plans to also manufacture and fly its own orbital launch vehicle, known as the New Glenn, from the Florida Space Coast. BE-4 had been expected to complete engine qualification testing by late 2018.[18] However, by August 2021, the flight engines for ULA have still not been qualified, and Ars Technica revealed in an in-depth article serious technical and managerial problems in the BE-4 program.[17]

In May 2019, Jeff Bezos unveiled Blue Origin's vision for space and also plans for a moon lander known as "Blue Moon",[19] set to be ready by 2024.[20] On July 20, 2021, Blue Origin sent its first crewed mission into space via its New Shepard rocket and spaceflight system. The flight was approximately 10 minutes, and crossed the Kármán Line. Blue Origin founder Jeff Bezos was part of the four member crew along with his brother Mark Bezos, Wally Funk, and Oliver Daemen.

History[]

This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: WP:PROSELINE. (July 2021) |

Blue Origin founder Jeff Bezos has been interested in space from an early age. A profile published in 2013 described a 1982 Miami Herald interview Bezos gave after he was named valedictorian of his high school class. The 18-year-old Bezos said he wanted "to build space hotels, amusement parks and colonies for 2 million or 3 million people who would be in orbit. 'The whole idea is to preserve the earth' he told the newspaper ... The goal was to be able to evacuate humans. The planet would become a park."[22]

In 1999, after watching the rocketry biopic film October Sky, Bezos discussed forming a space company with science-fiction author Neal Stephenson.[23][24] Blue Origin was founded in 2000 in Kent, Washington, and began developing both rocket propulsion systems and launch vehicles.[25] Since the founding, the company was quite secretive about its plans[26][27] and emerged from its "self-imposed silence" only after 2015.[25]

The company was incorporated in 2000 and in 2003, Bezos began buying land in Texas, at which point interested parties[who?] followed up on the purchases. This was a topic of some interest in local politics, and Bezos' rapid aggregation of land under a variety of whimsically named shell companies was called[by whom?] a "land grab".[28]

Rob Meyerson joined Blue Origin in 2003 and served as the company’s long-time president. Meyerson led the growth of the company from 10 to 1500 people before leaving in late 2018.[8]

As early as 2005, Bezos had discussed plans to create a vertical-takeoff and landing spaceship called New Shepard. Plans for New Shepard were initially kept quiet, but Blue Origin's website indicated Bezos' desire to, "lower the cost of spaceflight so that we humans can better continue exploring the solar system."[29][30][26] By 2008, a publicized timetable for New Shepard indicated that Blue Origin intended to fly uncrewed in 2011, and crewed in 2012.[31] In a 2011 interview, Bezos indicated that he founded Blue Origin to send customers into space by focusing on two objectives: to decrease the cost and to increase the safety of human spaceflight.[32] By late 2016, Blue Origin was projecting that if all New Shepard test flights operated as scheduled, they could begin flying passengers to space on the New Shepard in 2018.[33]

In July 2013, the company employed approximately 250 people.[34] By May 2015, the company had grown to approximately 400 employees, with 350 of those working on engineering, manufacturing and business operations in the Kent location[35] and approximately 50 in Texas supporting the engine-test and suborbital test-flight facility.[35] More rapid growth began in 2016. By April 2017, the company had more than 1000 employees.[25] In August 2018, the company was more than 1500 employees, more than double the number in early 2016, and stated that they expected that "to double again by the time New Glenn is flying."[36] But Blue had more than 2000 employees by April 2019 – two years before New Glenn's anticipated first flight – with plans to have more than 2600 by the end of 2019.[37]

By July 2014, Bezos had invested over US$500 million of his own money into Blue Origin.[38] As of 2016, Blue Origin was spending US$1 billion a year, funded by Jeff Bezos' sales of Amazon stock.[39] In both 2017, and again in 2018, Bezos made public statements that he intends to fund Blue Origin with US$1 billion per year from sales of his equity in Amazon.[40]

The first developmental test flight of the New Shepard occurred on April 29, 2015.[41] The uncrewed vehicle flew to its planned test altitude of more than 93.5 km (307,000 ft) and achieved a top speed of Mach 3.[42] In July 2015, NanoRacks, a provider of services such as payload design and development, safety approvals, and integration, announced a partnership with Blue Origin to provide standardized payload accommodations for experiments flying on Blue Origin's New Shepard suborbital vehicle.[43]

In September 2014, the company and United Launch Alliance (ULA) entered into a partnership whereby Blue Origin would produce a large rocket engine – the BE-4 – for the Vulcan, the successor to the 10,000–19,000-kilogram-class (22,000–42,000 lb) Atlas V which has launched US national security payloads since the early 2000s, and was then scheduled to exit service in the late 2010s.[25] The 2014 announcement added that Blue Origin had been working on the engine for three years prior to the public announcement, and that the first flight on the new rocket could occur as early as 2019.[44] In actuality, Atlas V is still flying in 2020. By April 2017, development and test of the 2,400 kN (550,000 lbf) BE-4 were progressing well and Blue Origin was expected to be selected for the ULA Vulcan rocket.[25] In April 2015, Blue Origin announced that it had completed acceptance testing of the BE-3 rocket engine that would power the New Shepard space capsule to be used for Blue Origin suborbital flights.[45]

On November 23, 2015, Blue Origin launched the New Shepard rocket to space for a second time[46] to an altitude of 100.53 km (329,839 ft), and vertically landed the rocket booster less than 1.5 meters (5 ft) from the center of the pad. The capsule descended to the ground under parachutes 11 minutes after blasting off and landed safely. This was the first time a suborbital booster had flown to space and returned to Earth.[47][48] This flight validated the vehicle architecture and design. The ring fin shifted the center of pressure aft to help control reentry and descent; eight large drag brakes deployed and reduced the vehicle's terminal speed to 623 km/h (387 mph); hydraulically actuated fins steered the vehicle through 192 km/h (119 mph) high-altitude crosswinds to a location precisely aligned with and 1,500 m (5,000 ft) above the landing pad; then the highly throttleable BE-3 engine re-ignited to slow the booster as the landing gear deployed, and the vehicle descended the last 30 m (100 ft) at 7.1 km/h (4.4 mph) to touchdown on the pad.[49] On January 22, 2016, Blue Origin re-flew the same New Shepard booster that launched and landed vertically in November 2015, demonstrating reuse. This time, New Shepard reached an apogee of 101.7 km (333,582 ft) before both capsule and booster returned to Earth for recovery and reuse. In April 2016, the same New Shepard booster again flew, now for a third time, reaching 103.4 km (339,178 ft), before again returning and landing successfully.[50]

In September 2015, Blue Origin announced details of an unnamed planned orbital launch vehicle, indicating that the first stage would be powered by its BE-4 rocket engine currently under development, while the second stage would be powered by its recently completed BE-3 rocket engine. In addition, Blue Origin announced that it would both manufacture and launch the new rocket from the Florida Space Coast. No payload or gross launch weight was given. Bezos noted in interviews that this new launch vehicle would not compete for US government national security missions, leaving that market to United Launch Alliance and SpaceX.[51] Science-fiction author Neal Stephenson worked part-time at Blue Origin into late 2006[52] and credited the company's employees for ideas and discussions leading to his 2015 novel, Seveneves.

In March 2016, Blue Origin invited journalists to see the inside of its Kent, Washington headquarters and manufacturing facility for the first time. The company was planning for substantial growth in 2016 as it planned to build more crew capsules and propulsion modules for the New Shepard program and ramp up BE-4 engine builds to support full-scale development testing. Blue indicated that employment was expected to grow to 1,000 in 2016 from 600 in February 2016.[53] Bezos also articulated a long-term vision for humans in space, seeing the potential to move much heavy industry completely off-Earth, "leaving our planet zoned strictly for 'residential and light industrial' use with an end state hundreds of years out "where millions of people would be living and working in space."[34] In March 2016, test flights carrying human occupants were said by the company to be possible as early as 2017, potentially with commercial service in 2018.[54] The newly disclosed orbital rocket – which would subsequently be named New Glenn – was planned to fly its initial flight in 2020.[34]

Also in March 2016, Bezos discussed his plans to offer space tourism services to space. Pointing out the "entertainment" aspect of the early "barnstormers" in really advancing aviation in the early days when such rides "were a big fraction of airplane flights in those early days," he sees space tourism playing a similar role: advancing "space travel and rocket launches, through tourism and entertainment."[55] On the other hand, as of 2016 there were no current plans to pursue the niche market of US military launches; Bezos said he is unsure where Blue Origin would add any value in that market.[55] This would later change.[9]

In September 2016, Blue announced that its orbital rocket would be named New Glenn in honor of the first American astronaut to orbit the Earth, John Glenn, and that the 7-meter-diameter (23 ft) first stage will be powered by seven Blue Origin BE-4 engines. The first stage is reusable and will land vertically, just like the New Shepard suborbital launch vehicle that preceded it.[56]

In March 2017, Bezos announced that Blue Origin had acquired its first paying launch customer for orbital satellite launches. Eutelsat is expected to start launching TV satellites in 2022 on Blue Origin's New Glenn orbital launch vehicle.[57] A day after announcing Eutelsat, Blue Origin introduced OneWeb as its second customer.[58] In September 2017, Blue Origin closed a deal for New Glenn with its first Asian customer, Mu Space.[59] The company, based in Thailand, plans to provide satellite-based broadband services and space travel in Asia-Pacific.[60]

In December 2017, Blue Origin launched a test experiment on New Shepard with a technology that could one day treat chest trauma in a space environment.[61]

In June 2018, Blue Origin indicated that while it continued to plan to fly initial internal passengers later in 2018, it would not be selling commercial tickets for New Shepard until 2019.[62]

In May 2019 Blue Origin announced the Blue Moon lander design concept,[63] expected to fly on the New Glenn launch vehicle and be ready to make a soft landing on the Moon as early as 2024. They also announced the BE-7 engine. The lander, part of Blue Origin's entry in NASA's Human Landing System competition, is slated to be able to be built in two versions, and transport 3.6–6.5 t (7,900–14,300 lb).[64]

Despite publicly announced plans to fly passengers on New Shepard in 2018 and begin commercial flights in 2019,[62] as of March 2021, Blue Origin had yet to fly commercial passengers (or indeed, any passengers) on the suborbital rocket.[9] On December 11, 2019, the company completed its twelfth test flight of the rocket.[65]

In early 2021, Blue announced a revised schedule estimate for the first launch of New Glenn.[9] While initially planned to fly as early as 2020[34] the company announced in March 2021 that New Glenn "would not launch until the fourth quarter of 2022, at the earliest."[9]

In June 2021, Blue Origin auctioned off a seat on the company's debut private astronaut mission for $28 million; however, the winner of the auction did not take part in the flight due to a scheduling conflict. The winner remained initially anonymous but later revealed himself as Justin Sun.[66] The launch took place on July 20, 2021, with Oliver Daemen flying in the seat that Mr. Sun had won in the auction.[67]

In August 2021, Blue Origin began a lawsuit against the United States federal government over its failed bid on the Human Landing System contract, which included the Blue Moon lander. Blue Origin claims NASA unlawfully and improperly evaluated the proposals. The US Government Accountability Office (GAO) investigated the allegations and sided with NASA. Blue Origin's lawsuit is causing delays to the Artemis program and NASA's planned moon landing.[68][69]

In October 2021, William Shatner (age 90), the actor who played Captain Kirk on the Original Star Trek series, boarded a Blue Origin sub-orbital capsule and successfully flew to space becoming the oldest person to fly to space.[70][71]

The third manned mission of New Shepard launched 11 December 2021.

Vehicles and Projects[]

Charon[]

Blue Origin's first flight test vehicle, called Charon after Pluto's moon,[72] was powered by four vertically mounted Rolls-Royce Viper Mk. 301 jet engines rather than rockets. The low-altitude vehicle was developed to test autonomous guidance and control technologies, and the processes that the company would use to develop its later rockets. Charon made its only test flight at Moses Lake, Washington on March 5, 2005. It flew to an altitude of 96 m (316 ft) before returning for a controlled landing near the liftoff point.[73][74]

As of 2016, Charon is on display at the Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington.[75]

Goddard[]

The next test vehicle, named Goddard (also known as PM1), first flew on November 13, 2006. The flight was successful. A test flight for December 2 never launched.[76][77] According to Federal Aviation Administration records, two further flights were performed by Goddard.[78]

New Shepard[]

This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: WP:PROSELINE. (July 2021) |

Blue Origin's New Shepard suborbital spaceflight system is composed of two vehicles: a crew capsule accommodating three or more astronauts launched by a rocket booster. The two vehicles lift off together and are designed to separate during flight. After separation, the booster is designed to return to Earth to perform a vertical landing while the crew capsule follows a separate trajectory, returning under parachutes for a land touchdown. Both vehicles are intended for recovery and re-use.[79] New Shepard is controlled entirely by on-board computers.[80] In addition to flying astronauts, New Shepard is intended to provide frequent opportunities for researchers to fly experiments into suborbital space.[81]

A Federal Aviation Administration NOTAM indicated that a flight test of an early suborbital test vehicle – PM2 – was scheduled for August 24, 2011.[82] The flight in west Texas failed when ground personnel lost contact and control of the vehicle. Blue Origin released its analysis of the failure nine days later. As the vehicle reached a speed of Mach 1.2 and 14 km (46,000 ft) altitude, a "flight instability drove an angle of attack that triggered [the] range safety system to terminate thrust on the vehicle".[83]

In October 2012, Blue Origin conducted a successful New Shepard pad escape test at its West Texas launch site, firing its pusher escape motor and launching a full-scale crew capsule from a launch vehicle simulator. The crew capsule traveled to an altitude of 703 m (2,307 ft) under active thrust vector control before descending safely by parachute to a soft landing 500 m (1,630 ft) downrange.[84]

In April 2015, Blue Origin announced its intent to begin autonomous test flights of New Shepard in 2015 as frequently as monthly. Blue Origin expected "a series of dozens of flights over the extent of the test program [taking] a couple of years to complete".[45]

New Shepard made its first test flight on April 29, 2015. The uncrewed vehicle flew to its planned test altitude of more than 93.5 km (307,000 ft) and achieved a top speed of Mach 3.[42] The crew capsule separated from the booster before returning to Earth and landing under parachutes. The booster experienced a hydraulic failure that prevented it from landing and was destroyed on impact.[85]

On November 23, 2015, New Shepard made its second test flight, reaching 100.5 km (330,000 ft) altitude with a successful vertical landing and recovery of the booster, the first time a booster stage that had been to space had ever done so.[86][87] The crew capsule was also successfully recovered via parachute return, as Blue had done before.[87]

On January 22, 2016, Blue Origin re-flew the same New Shepard booster that launched and landed vertically in November 2015, demonstrating reuse. This time, New Shepard reached an apogee of 101.7 km (333,582 ft) before both capsule and booster again successfully returned to Earth with a soft landing for recovery and reuse.[88]

Additional flights of New Shepard propulsion module 2 (NS2) were flown on April 2, 2016, reaching 103.4 km (339,178 ft),[89] and on June 19, 2016, for a fourth time, again reaching over 100.6 km (330,000 ft), before again returning and landing successfully.[90] A fifth and final test flight of NS2 took place in October 2016 before NS2 was retired.[citation needed]

The first flight of the third booster took place in December 2017.[citation needed]

The seventh test launch of New Shepard NS3 on October 13, 2020, successfully reached a maximum altitude of 105 km (346,000 ft).[91] On January 14, 2021, New Shepard successfully performed the first test flight of the New Shepard 4 (NS4), the fourth propulsion module to be built. It reached a maximum altitude of almost 107 km (350,827 ft).[92] On the April 14, 2021, New Shepard successfully performed a landing with the reused rocket from the last flight.[93]

On July 20, 2021, New Shepard carried its first four passengers to suborbital space[citation needed]. The passengers were Jeff Bezos, his brother Mark Bezos, Wally Funk, and Oliver Daemen, after the unnamed auction winner (later revealed to have been Justin Sun[94]) dropped out due to a scheduling conflict. The second and third manned missions of New Shepard took place in October and December 2021, respectively.[citation needed]

New Glenn[]

The New Glenn is a 7-meter (23 ft)-diameter two-stage orbital launch vehicle that is expected to launch in 2022.[95]

The design work on the vehicle began in 2012. The high-level specifications for the vehicle were publicly announced in September 2016.[56]

The first stage will be powered by seven BE-4 engines, also designed and manufactured by Blue Origin. The first stage is reusable, just like the New Shepard suborbital launch vehicle that preceded it. The second stage is intended to be expendable.[56]

Blue Origin intends to launch the rocket from Cape Canaveral Launch Complex 36, and manufacture the rockets at a new facility on nearby land in Exploration Park. Acceptance testing of the BE-4 engines will also be done in Florida.[96]

Orbital subsystems and earlier development work[]

Blue Origin began developing systems for orbital human spacecraft prior to 2012. A reusable first-stage booster was projected to fly a suborbital trajectory, taking off vertically like the booster stage of a conventional multistage rocket. Following stage separation, the upper stage would continue to propel astronauts to orbit while the first-stage booster would descend to perform a powered vertical landing similar to the New Shepard suborbital Propulsion Module. The first-stage booster would be refueled and launched again, allowing improved reliability and lowering the cost of human access to space.[79]

The booster rocket was projected to loft Blue Origin's biconic Space Vehicle to orbit, carrying astronauts and supplies. After orbiting the Earth, the Space Vehicle will reenter Earth's atmosphere to land on land under parachutes, and then be reused on future missions to Earth orbit.[79]

Blue Origin successfully completed a System Requirements Review (SRR) of its orbital Space Vehicle in May 2012.[97]

Engine testing for the Reusable Booster System (RBS) vehicle began in 2012. A full-power test of the thrust chamber for Blue Origin BE-3 liquid oxygen, liquid hydrogen rocket engine was conducted at a NASA test facility in October 2012. The chamber successfully achieved full thrust of 100,000 pounds-force (about 440 kN).[98]

New Armstrong[]

At the time of the announcement of New Glenn in 2016, Jeff Bezos revealed that the next project after New Glenn would be called New Armstrong, without detailing what that would be. Media have speculated that New Armstrong would be a launch vehicle named after Neil Armstrong, the first man to walk on the Moon.[99][100]

Blue Moon[]

The Blue Moon lander is a crew-carrying lunar lander unveiled in 2019.[63] The standard version of the lander is intended to transport 3.6 t (7,900 lb) to the lunar surface whereas a "stretched tank variant" could land up to 6.5 t (14,000 lb) on the Moon, both making a soft landing. The lander will use the BE-7 hydrolox engine.[64]

Project Jarvis[]

Information became public in July 2021 that in recent months Blue Origin had begun a "project to develop a fully reusable upper stage for New Glenn."[101] A principle goal of the project is to reduce the overall launch cost of New Glenn by gaining an operational capacity to reuse second stages, just as SpaceX is aiming to do with their Starship second stage by building a fully-reusable orbital launch vehicle. Jarvis is focusing on developing a stainless steel propellant tank structure for the second stage rocket, and evaluating it as a part of a solution for a complete second stage system.[102] If Blue is able to realize such a second stage design, and bring it into operational use, it would substantially bring down the cost of launches of the New Glenn system.[101]

Beyond the technical changes indicated, CEO Bezos has created a new management structure for Project Jarvis, walling off "parts of the second-stage development program from the rest of Blue Origin [telling] its leaders to innovate in an environment unfettered by rigorous management and paperwork processes."[101] No budget nor timetable has been publicly released.

On 24 August 2021, Blue had rolled a stainless steel test tank to their Launch Complex 36 facility. Ground pressure testing with cyrogenic propellants was expected to begin as early as September 2021.[102][needs update]

Orbital Reef[]

On October 25th 2021 Blue Origin announced that together with Sierra Space it would build a "Mixed-use space business park" in LEO called Orbital Reef, to "open multiple new markets in space, [and] provide anyone with the opportunity to establish their own address on orbit." It "will offer research, industrial, international, and commercial customers the cost competitive end-to-end services they need including space transportation and logistics, space habitation, equipment accommodation, and operations including onboard crew. The station will start operating in the second half of this decade."[103] Further partners are Boeing, Redwire Space, , and Arizona State University.[104]

Rocket engines[]

Following Aerojet’s acquisition of Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne in 2012, Blue Origin president Rob Meyerson saw an opportunity to fill a gap in the defense industrial base. Blue Origin publicly entered the liquid rocket engine business by partnering with ULA on the development of the BE-4, and working with other companies. Meyerson announced the selection of Huntsville, Alabama as the location of Blue Origin’s rocket production factory in June 2017.[105][106]

BE-1[]

Blue Engine 1, or BE-1, was the first rocket engine developed by Blue Origin and was used on the company's Goddard development vehicle. The pressure-fed monopropellant engine was powered by peroxide and produced 9.8 kN (2,200 lbf) of thrust.[107][108]

BE-2[]

Blue Engine 2, or BE-2, was a pump-fed bipropellant engine burning kerosene and peroxide which produced 140 kN (31,000 lbf) of thrust.[107][108] Five BE-2 engines powered Blue Origin's PM-2 development vehicle on two test flights in 2011.[109]

BE-3[]

Blue Origin publicly announced the development of the Blue Engine 3, or BE-3, in January 2013, but the engine had begun development in the early 2010s. BE-3 is a new liquid hydrogen/liquid oxygen (LH2/LOX) cryogenic engine that can produce 490 kN (110,000 lbf) of thrust at full power, and can be throttled down to as low as 110 kN (25,000 lbf) for use in controlled vertical landings.[110]

Early thrust chamber testing began at NASA Stennis[111] in 2013.[112]

By late 2013, the BE-3 had been successfully tested on a full-duration suborbital burn, with simulated coast phases and engine relights, "demonstrating deep throttle, full power, long-duration and reliable restart all in a single-test sequence."[110] NASA has released a video of the test.[112] As of December 2013, the engine had demonstrated more than 160 starts and 9,100 seconds (2.5 h) of operation at Blue Origin's test facility near Van Horn, Texas.[110][113]

BE-3 engine acceptance testing was completed by April 2015 with 450 test firings of the engine and a cumulative run time of more than 30,000 seconds (8.3 h). The BE-3 engine powers the New Shepard space capsule that is being used for Blue Origin suborbital flights that began in 2015.[45]

BE-3U[]

The BE-3U engine is a modified BE-3 for use on upper stages of Blue Origin orbital launch vehicles. The engine will include a nozzle better optimized for operation under vacuum conditions as well as a number of other manufacturing differences since it is an expendable engine whereas the BE-3 is designed for reusability.[27]

BE-4[]

Blue Origin began work on a new and much larger rocket engine in 2011. The new engine, the Blue Engine 4, or BE-4, is a change for Blue Origin in that it is their first engine that will combust liquid oxygen and liquid methane propellants. The engine has been designed to produce 2,400 kN (550,000 lbf) of thrust, and was initially planned to be used exclusively on a Blue Origin proprietary launch vehicle. Blue Origin did not announce the new engine to the public until September 2014.[114]

In late 2014, Blue Origin signed an agreement with United Launch Alliance (ULA) to co-develop the BE-4 engine, and to commit to use the new engine on an upgraded Atlas V launch vehicle, replacing the single RD-180 Russian-made engine. The new launch vehicle will use two of the 2,400 kN (550,000 lbf) BE-4 engines on each first stage. The engine development program began in 2011.[44][114]

When announced in 2014, and still in March 2016, and then in November 2019 ULA expected the first flight of the new launch vehicle – the Vulcan – no earlier than July 2021.[114][34][115][116] As of March 2018, Blue Origin intended to complete engine qualification testing by late 2018.[18]

In the event, by August 2021 it had become clear, and publicly so, that the engine program is in trouble, and qualification testing was still not yet complete. The first flight test of the new engine is now expected no earlier than 2022 on the Vulcan rocket, and much later on Blue's own New Glenn. The engine is running four years behind schedule, and Blue has experienced a variety of problems, both technical and managerial. Flight engines will not be delivered to ULA before late 2021, and perhaps not until early 2022.[17] Moreover, the business relationship with ULA has deteriorated, in part because Blue tried to renegotiate for a higher price for the BE-4 engines in 2017 than had been agreed to in 2014.[17]

BE-7[]

The BE-7 engine, currently under development, is being designed for use on a lunar lander.[117] Its first ignition tests[118] were performed June 2019. The BE-7 is designed to produce 40 kN (10,000 lbf) of thrust and have a deep throttle range, making it less powerful than the other engines Blue Origin has in development/production, but this low thrust is advantageous for its intended purpose as a Lunar vehicle descent stage main propulsion system as it offers greater control for soft landings.

The engine uses hydrogen and oxygen propellants in a dual-expander combustion cycle, similar to the more typical expander cycle used by the RL-10 and others, which in theory offers better performance and allows each pump to run at independent flow rates. Blue Origin plans to use additive manufacturing technology to produce the combustion chamber of the engine, which would allow them to more cheaply construct the complex cooling channels required to keep the engine from melting and to produce the hot gasses that will power the pumps.[119]

Pusher escape motor[]

Blue Origin partnered with Aerojet Rocketdyne to develop a pusher launch escape system for the New Shepard suborbital Crew Capsule. Aerojet Rocketdyne provides the Crew Capsule Escape Solid Rocket Motor (CCE SRM) while the thrust vector control system that steers the capsule during an abort is designed and manufactured by Blue Origin.[120][121]

In late 2012, Blue Origin performed a pad abort test of the escape system on a full-scale suborbital capsule.[84] Four years later in 2016, the escape system was successfully tested in-flight at the point of highest dynamic pressure as the vehicle reached transonic velocity.[122]

Facilities[]

Blue Origin has a development facility near Seattle, Washington, and a privately owned spaceport in West Texas. Blue Origin has continued to expand its Seattle-area office and rocket production facilities in 2016 – purchasing an adjacent 11,000 m2 (120,000 sq ft)-building[123] – and 2017, with permits filed to build a new 21,900 m2 (236,000 sq ft) warehouse complex and an additional 9,560 m2 (102,900 sq ft) of office space.[124] The company's established a new headquarters and R&D facility, dubbed the O’Neill Building, in Kent, Washington, on June 6, 2020.[125][126]

Blue Origin manufactures rocket engines, launch vehicles, and space capsules in Washington. Its largest engine – BE-4 – will be produced at a new manufacturing facility in Huntsville, Alabama, which was first announced in 2017[127] and opened in February 2020.[128] In 2017, Blue Origin established a manufacturing facility for launch vehicles in Florida near where they will launch New Glenn from the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, after initiating design and construction in 2015.[55][53][129]

The west Texas suborbital launch site is at 31°25'22.6"N 104°45'25.6"W (31.422949, -104.757120), about 20 miles north of Van Horn, Texas.

At Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, from 2016, Blue Origin have been converting Launch Complex 36 (LC-36) to launch New Glenn to orbit.[130]

Flights[]

1

2

3

4

5

6

2005

2010

2015

2020

|

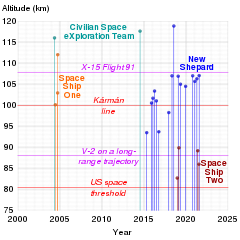

Timeline of SpaceShipOne, SpaceShipTwo, CSXT and New Shepard sub-orbital flights. Where booster and capsule achieved different altitudes, the higher is plotted. In the SVG file, hover over a point to show details. |

| Flight No. | Date | Vehicle | Apogee | Outcome | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | March 5, 2005 | Charon | 315 ft (96 m)[73] | Success | |

| 2 | November 13, 2006 | Goddard | 279 ft (85 m)[131] | Success | First rocket-powered test flight[132] |

| 3 | March 22, 2007 | Goddard ♺[133] | Success | ||

| 4 | April 19, 2007 | Goddard ♺[134] | Success | ||

| 5 | May 6, 2011 | PM2 (Propulsion Module)[135] | Success | [136] | |

| 6 | August 24, 2011 | PM2 (Propulsion Module) ♺ | Failure | [136] | |

| 7 | October 19, 2012 | New Shepard capsule | Success | Pad escape test flight,[84] | |

| 8 | April 29, 2015 | New Shepard 1 | 307,000 ft (93.5 km) | Partial success | Flight to altitude 93.5 km, capsule recovered, booster crashed on landing[137] |

| 9 | November 23, 2015 | New Shepard 2 | 329,839 ft (100.535 km)[87] | Success | Sub-orbital spaceflight and landing[138] |

| 10 | January 22, 2016 | New Shepard 2 ♺ | 333,582 ft (101.676 km)[citation needed] | Success | Sub-orbital spaceflight and landing of a reused booster[139] |

| 11 | April 2, 2016 | New Shepard 2 ♺ | 339,178 ft (103.381 km)[140] | Success | Sub-orbital spaceflight and landing of a reused booster[50] |

| 12 | June 19, 2016 | New Shepard 2 ♺ | 331,501 ft (101.042 km)[141] | Success | Sub-orbital spaceflight and landing of a reused booster: The fourth launch and landing of the same rocket. Blue Origin published a live webcast of the takeoff and landing.[141] |

| 13 | October 5, 2016 | New Shepard 2 ♺ | Booster: 307,458 ft (93.713 km)

Capsule: 23,269 ft (7.092 km)[142] |

Success | Sub-orbital spaceflight and landing of a reused booster. Successful test of the in-flight abort system. The fifth and final launch and landing of the same rocket (NS2).[122] |

| 14 | December 12, 2017 | New Shepard 3 | Booster: 322,032 ft (98.155 km)

Capsule: 322,405 ft (98.269 km)[143] |

Success | Flight to just under 100 km and landing. The first launch of NS3 and a new Crew Capsule 2.0.[144] |

| 15 | April 29, 2018 | New Shepard 3 ♺ | 351,000 ft (107 km)[145] | Success | Sub-orbital spaceflight and landing of a reused booster.[146] |

| 16 | July 18, 2018 | New Shepard 3 ♺ | 389,846 ft (118.825 km)[147] | Success | Sub-orbital spaceflight and landing of a reused booster, with the Crew Capsule 2.0–1 RSS H.G.Wells, carrying a mannequin. Successful test of the in-flight abort system at high altitude. Flight duration was 11 minutes.[147] |

| 17 | January 23, 2019 | New Shepard 3 ♺ | Approx. 351,000 ft (106.9 km)[citation needed] | Success | Sub-orbital flight, delayed from December 18, 2018. Eight NASA research and technology payloads were flown.[148][149] |

| 18 | May 2, 2019 | New Shepard 3 ♺ | Approx. 346,000 ft (105 km)[150] | Success | Sub-orbital flight. Max Ascent Velocity: 2,217 mph (3,568 km/h),[150] duration: 10 minutes, 10 seconds. Payload: 38 microgravity research payloads (nine sponsored by NASA). |

| 19 | December 11, 2019 | New Shepard 3 ♺ | Approx. 343,000 ft (104.5 km)[151] | Success | Sub-orbital flight, Payload: Multiple commercial, research (8 sponsored by NASA) and educational payloads, including postcards from Club for the Future.[152][153][151] |

| 20 | October 13, 2020 | New Shepard 3 ♺ | Approx. 346,000 ft (105.4 km) | Success | 7th flight of the same capsule/booster. Onboard 12 payloads include Space Lab Technologies, Southwest Research Institute, postcards and seeds for Club for the Future, and multiple payloads for NASA including SPLICE to test future lunar landing technologies in support of the Artemis program[154] |

| 21 | January 14, 2021 | New Shepard 4 | 350,858 ft (106 km) | Success | Uncrewed qualification flight for NS4 rocket and "RSS First Step" capsule and maiden flight for NS4.[155] |

| 22 | April 14, 2021 | New Shepard 4 ♺ | 348,753 ft (106 km) | Success | 2nd flight of NS4 with Astronaut Rehearsal. Gary Lai, Susan Knapp, Clay Mowry, and Audrey Powers, all Blue Origin personnel, are "stand-in astronauts". Lai and Powers briefly get in.[156] |

| 23 | July 20, 2021 | New Shepard 4 ♺ | 351,210 ft (107 km) | Success | New Shepard launch no. 16, First flight with Bezos |

| 24 | August 26, 2021[157] | New Shepard 3 ♺ | 347,434 ft (106 km) | Success | Payload mission consisting of 18 commercial payloads inside the crew capsule, a NASA lunar landing technology demonstration installed on the exterior of the booster and an art installation installed on the exterior of the crew capsule.[158] |

| 25 | October 13, 2021 | New Shepard 4 ♺ | 341,434 ft (106 km) | Success | Second manned mission with William Shatner |

| 26 | December 11, 2021 | New Shepard 4 ♺ | Success | Third manned mission with Michael Strahan |

Funding[]

By July 2014, Jeff Bezos had invested over US$500 million into Blue Origin.[38] By March 2016, the vast majority of funding to support technology development and operations at Blue Origin has come from Jeff Bezos' private investment, but Bezos had declined to publicly state the amount[53] prior to 2017 when an annual amount was stated publicly – as of April 2017, Bezos was selling approximately US$1 billion in Amazon stock each year to privately finance Blue Origin.[39] Bezos was criticized by philanthropists for spending so much of his vast wealth to fund Blue Origin and his personal flight into space instead of addressing the needs of people on Earth. Bezos said his critics were "largely right" and: "We have lots of problems here and now on Earth and we need to work on those. And we always need to look to the future. We've always done that as a species, as a civilization. We have to do both."[159]

Blue Origin will receive up to $500 million from the United States Air Force over the period 2019–2024 if they are a finalist in the Launch Services Agreement competition,[160] of which they have received at least $181 million so far.[161] Blue Origin has also completed work for NASA on several small development contracts, receiving total funding of US$25.7 million by 2013.[162][163] However, the U.S. Space Force on December 31, 2020, officially terminated launch technology partnerships signed in October 2018 with Blue Origin and Northrop Grumman, as neither company had won a National Security Space Launch procurement contract in the meantime. As a result of the lost contract, management has pushed the New Glenn launch to late 2022 as part of a "re-baselined" effort to organize resources for future launches.[164]

Collaborations[]

With NASA[]

Blue Origin has contracted to do work for NASA on several development efforts. The company was awarded US$3.7 million in funding in 2009 by NASA via a Space Act Agreement[162][165] under the first Commercial Crew Development (CCDev) program for development of concepts and technologies to support future human spaceflight operations.[166][167] NASA co-funded risk-mitigation activities related to ground testing of (1) an innovative 'pusher' escape system, that lowers cost by being reusable and enhances safety by avoiding the jettison event of a traditional 'tractor' Launch Escape System, and (2) an innovative composite pressure vessel cabin that both reduces weight and increases safety of astronauts.[162] This was later revealed to be a part of a larger system, designed for a biconic capsule, that would be launched atop an Atlas V rocket.[168] On November 8, 2010, it was announced that Blue Origin had completed all milestones under its CCDev Space Act Agreement.[169]

In April 2011, Blue Origin received a commitment from NASA for US$22 million of funding under the CCDev phase 2 program.[163] Milestones included (1) performing a Mission Concept Review (MCR) and System Requirements Review (SRR) on the orbital Space Vehicle, which utilizes a biconic shape to optimize its launch profile and atmospheric reentry, (2) further maturing the pusher escape system, including ground and flight tests, and (3) accelerating development of its BE-3 LOX/LH2 440 kN (100,000 lbf) engine through full-scale thrust chamber testing.[170]

In 2012, NASA's Commercial Crew Program released its follow-on CCiCap solicitation for the development of crew delivery to ISS by 2017. Blue Origin did not submit a proposal for CCiCap, but is reportedly continuing work on its development program with private funding.[171] Blue Origin had a failed attempt to lease a different part of the Space Coast, when they submitted a bid in 2013 to lease Launch Complex 39A (LC39A) at the Kennedy Space Center – on land to the north of, and adjacent to, Cape Canaveral AFS – following NASA's decision to lease the unused complex out as part of a bid to reduce annual operation and maintenance costs. The Blue Origin bid was for shared and non-exclusive use of the LC39A complex such that the launchpad was to have been able to interface with multiple vehicles, and costs for using the launch pad were to have been shared across multiple companies over the term of the lease. One potential shared user in the Blue Origin notional plan was United Launch Alliance. Commercial use of the LC39A launch complex was awarded to SpaceX, which submitted a bid for exclusive use of the launch complex to support their crewed missions.[172]

In September 2013 – before completion of the bid period, and before any public announcement by NASA of the results of the process – Florida Today reported that Blue Origin had filed a protest with the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) "over what it says is a plan by NASA to award an exclusive commercial lease to SpaceX for use of mothballed space shuttle launch pad 39A".[173] NASA had originally planned to complete the bid award and have the pad transferred by October 1, 2013, but the protest delayed a decision until the GAO reached a decision on the protest.[173][174] SpaceX said that they would be willing to support a multi-user arrangement for pad 39A.[175] In December 2013, the GAO denied the Blue Origin protest and sided with NASA, which argued that the solicitation contained no preference on the use of the facility as either multi-use or single-use. "The [solicitation] document merely [asked] bidders to explain their reasons for selecting one approach instead of the other and how they would manage the facility".[174] NASA selected the SpaceX proposal in late 2013 and signed a 20-year lease contract for Launch Pad 39A to SpaceX in April 2014.[176]

On April 30, 2020, Blue Origin's National Team, which includes Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and Draper, was awarded $579 million to develop an integrated human landing system as part of NASA's Artemis program to return humans to the Moon.[177][178] On April 16, 2021, NASA awarded the Artemis moon lander work, in full, to the rival SpaceX bid.[179] On April 26, 2021, Blue Origin filed a protest with the Government Accountability Office, citing NASA's failure "... to allow offerors to meaningfully compete for an award when the Agency's requirements changed due to its undisclosed, perceived shortfall of funding ...", as well as the Agency's performance of a "... flawed competitive acquisition in contravention of BAA rules and requirements".[180][181] On July 30, 2021, the GAO denied Blue Origin's protest.[182]

With ULA[]

In September 2018, it was announced that Blue Origin's BE-4 engine had been selected by United Launch Alliance to provide first-stage rocket engines for ULA's next-generation booster design, the Vulcan rocket. The BE-4 engine is set to replace the Russian-built RD-180 currently powering ULA's Atlas V.[183]

With Mars Aerospace Company[]

Blue Origin worked with the Mars Aerospace Company[184] to help design a future propulsion system that would allow large scale transport to Mars.

With military agencies[]

Blue Origin cooperated[clarification needed] with Boeing in Phase 1 of the DARPA XS-1 spaceplane program.[185] Blue Origin was reportedly in contracting talks with the United States Space Force as well according to Lt. General David Thompson.[186] However, such talks ceased as of December 31, 2020.

See also[]

- Armadillo Aerospace

- Blue Origin landing platform ship

- Interorbital Systems

- Kankoh-maru

- List of crewed spacecraft

- Lockheed Martin X-33

- Lunar Lander Challenge

- Masten Space Systems

- McDonnell Douglas DC-X

- NewSpace

- Quad (rocket)

- Reusable Vehicle Testing program by JAXA

- SpaceX reusable launch system development program

- VentureStar

- Zarya

References[]

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (April 18, 2018). "Blue Origin's new rocket engine will be able to launch '100 full missions,' CEO says". Cnbc.com. Archived from the original on May 27, 2019. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ^ "An unleashed Jeff Bezos will seek to shift space venture Blue Origin into hyperdrive". Reuters. February 8, 2021.

- ^ Alan Boyle. "Blue Origin's expansion plans rush ahead at its Seattle-area HQ – and in Los Angeles". GeekWire – via Yahoo! News.

- ^ "Blue Origin LLC | Financial Times". www.ft.com. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ "Blue Origin LLC – Company Profile and News". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ Staff Reporter (January 24, 2019). "Kent's Blue Origin racks up another successful New Shepard launch into space". Kent Reporter. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ Berger, Eric (April 2, 2016). "Why Blue Origin's latest launch is a huge deal for cheap space access". Ars Technica. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ a b "Former Blue Origin president Rob Meyerson leaves Jeff Bezos' space venture". GeekWire. November 8, 2018. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Berger, Eric (March 1, 2021). "Blue Origin's massive New Glenn rocket is delayed for years. What went wrong?". Ars Technica. Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- ^ "Gradatim Ferociter! Jeff Bezos explains Blue Origin's motto, logo … and the boots". GeekWire. October 25, 2016. Archived from the original on January 21, 2018. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- ^ "Blue Origin". Blue Origin. Archived from the original on December 6, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ "Blue Origin Engineer Talks Next Steps for New Shepard, New Glenn". Space.com. Archived from the original on January 26, 2018. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- ^ Grush, Loren (December 10, 2019). "Blue Origin successfully launches and lands its New Shepard rocket during 12th overall test flight". The Verge. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ "Blue Origin moves closer to human spaceflight with 12th New Shepard launch". TechCrunch. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ "Jeff Bezos Says Blue Origin Will Put People in Space in 2019". Fortune. Archived from the original on January 23, 2019. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ Palmer, Katie. "Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin Rocket Took Off and Landed – Again". Wired. Wired.com. Archived from the original on January 23, 2016. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Berger, Eric (August 5, 2021). "Blue Origin's powerful BE-4 engine is more than four years late – here's why". Ars Technica. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ a b Foust, Jeff (April 19, 2018). "Blue Origin expects BE-4 qualification tests to be done by year's end". SpaceNews. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (May 9, 2019). "Jeff Bezos Unveils Blue Origin's Vision for Space, and a Moon Lander". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 10, 2019. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Jeff Bezos aims Blue Origin at the Moon". TechCrunch. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ "NasaTelevision: Commercial Crew Progress Status Update". Youtube.com. January 9, 2013. Archived from the original on January 8, 2016. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ Whoriskey, Peter (August 11, 2013). "For Jeff Bezos, a new frontier". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 16, 2017. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- ^ Davenport, Christian (2018). The Space Barons: Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and the Quest to Colonize the Cosmos. PublicAffairs, an imprint owned by Hachette Book Group. ISBN 978-1610398299.

- ^ Jeff Foust (March 26, 2018). "Reviews: Rocket Billionaires and The Space Barons". The Space Review. Archived from the original on April 1, 2018. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - ^ a b c d e de Selding, Peter B. (April 14, 2017). "Blue Origin's older than SpaceX in more ways than one". Space Intel Report. Archived from the original on April 16, 2017. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- ^ a b Alan Boyle (June 24, 2006). "Blue's Rocket Clues". msnbc. Archived from the original on April 11, 2008. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- ^ a b Foust, Jeff (December 7, 2013). "Blue Origin shows off its engine". NewSpace Journal. Archived from the original on December 14, 2013. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ^ Mylene Mangalindan (November 10, 2006). "Buzz in West Texas is about Jeff Bezos space craft launch site". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on December 24, 2017. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- ^ "Accidents Won't Stop Private Space Industry's Push to Final Frontier". WIRED. Archived from the original on July 17, 2018. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ^ Michael Graczyk (March 15, 2005). "Blue Origin Spaceport Plans are Talk of Texas Town". space.com. Archived from the original on July 24, 2008. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- ^ [1] Archived December 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Levy, Stephen (November 13, 2011). "Jeff Bezos Owns the Web in More Ways Than You Think". Wired. Archived from the original on December 10, 2011. Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- ^ Morris, David (October 15, 2016). "Blue Origin Will Take Tourists to Space by 2018". Fortune.com. Archived from the original on December 3, 2016. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Boyle, Alan (March 5, 2016). "Jeff Bezos lifts curtain on Blue Origin rocket factory, lays out grand plan for space travel that spans hundreds of years". GeekWire. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved March 9, 2016.

- ^ a b "Local engineers aim high for cheaper spaceflight". The Seattle Times. May 31, 2015. Archived from the original on July 18, 2015. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- ^ Johnson, Eric M. (August 2, 2018). "Bezos throws cash, engineers at rocket program as space race accelerates". Reuters. Archived from the original on August 3, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- ^ Replay of NS-11 Webcast Archived May 5, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, at 13:03, Blue Origin, via YouTube, May 2, 2019, accessed May 5, 2019.

- ^ a b Foust, Jeff (July 18, 2014). "Bezos Investment in Blue Origin Exceeds $500 Million". Space News. Archived from the original on July 19, 2014. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ a b St. Fleur, Nicholas (April 5, 2017). "Jeff Bezos Says He was Selling $1 Billion a Year in Amazon Stock to Finance Race to Space". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 7, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- ^ Jeff Bezos reveals what it's like to build an empire and become the richest man in the world – and why he's willing to spend $1 billion a year to fund the most important mission of his life Archived April 30, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Business Insider, April 28, 2018, accessed May 1, 2018.

- ^ "Watch the incredible first test flight of Jeff Bezos's mysterious new rocket". Business Insider. Archived from the original on July 17, 2018. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ^ a b Foust, Jeff (April 30, 2015). "Senior Staff Writer". Space News. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (July 16, 2015). "NanoRacks And Blue Origin Team To Fly Suborbital Research Payloads". SpaceNews.

- ^ a b Achenbach, Joel (September 17, 2014). "Jeff Bezos's Blue Origin to supply engines for national security space launches". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 25, 2014. Retrieved September 27, 2014.

- ^ a b c Foust, Jeff (April 13, 2015). "Blue Origin's suborbital plans are finally ready for flight". Archived from the original on April 18, 2015. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

We've recently completed acceptance testing, meaning we've accepted the engine for suborbital flight on our New Shepard vehicle, [the end of a] very, very long development program [of] 450 test firings of the engine and a cumulative run time of more than 500 min [8.3 h]. The completion of those tests sets the stage for Blue Origin to begin test flights of the vehicle later this year at its facility in West Texas [where they] expect a series of flight tests with this vehicle ... flying in autonomous mode ... We expect a series of dozens of flights over the extent of the test program [taking] a couple of years to complete.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (November 24, 2015). "Journalist". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 25, 2015. Retrieved November 24, 2015.

- ^ Cofeld, Calla (November 25, 2015). "Staff Writer". Space.com. Space.com. Archived from the original on November 26, 2015. Retrieved November 25, 2015.

- ^ "Blue Origin Launches Bezos's Space Dreams and Lands a Rocket". Archived from the original on November 25, 2015. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ^ Bezos, Jeff. "Historic Rocket Landing". www.blueorigin.com. Blue Origin. Archived from the original on December 10, 2015. Retrieved November 23, 2015.

- ^ a b Calandrelli, Emily (April 2, 2016). "Blue Origin launches and lands the same rocket for a third time". Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (September 15, 2015). "Bezos Not Concerned About Competition, Possible ULA Sale". Space News. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ^ [2] Archived August 13, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Foust, Jeff (March 8, 2016). "Blue Origin plans growth spurt this year". SpaceNews. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ^ Fedde, Corey (March 9, 2016). "How Blue Origin plans to soon send people into space, safely". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ^ a b c Price, Wayne T. (March 12, 2016). "Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin could change the face of space travel". Florida Today. Archived from the original on January 6, 2018. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ^ a b c Bergin, Chris (September 12, 2016). "Blue Origin introduce the New Glenn orbital LV". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on September 13, 2016. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ Cecilia King (March 7, 2017). "Blue Origin, Jeff Bezos's Moon Shot, Gets First Paying Customer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 2, 2017. Retrieved May 5, 2017.

- ^ "Jeff Bezos adds OneWeb satellite venture to Blue Origin's New Glenn launch manifest". GeekWire. March 8, 2017. Archived from the original on January 26, 2018. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- ^ "The Rocket Company of Jeff Bezos Has Its First Asian Customer". Finance.co.uk. September 26, 2017. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- ^ "Blue Origin announces satellite launch deal with Thai telecom startup Mu Space". GeekWire. September 26, 2017. Archived from the original on January 25, 2018. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- ^ "NASA Funds Flight for Space Medical Technology on Blue Origin". link.galegroup.com. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ a b Foust, Jeff (June 21, 2018). "Blue Origin plans to start selling suborbital spaceflight tickets next year". SpaceNews. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ a b Sheetz, Michael (May 9, 2019). "Jeff Bezos unveils Blue Origin's Blue Moon lunar lander for astronauts". CNBC. Archived from the original on May 10, 2019. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ a b Clark, Stephen (May 9, 2019). "Jeff Bezos unveils 'Blue Moon' lander". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on May 10, 2019. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ^ Jackie Wattles (December 11, 2019). "Jeff Bezos's Blue Origin launches 12th test flight of space tourism rocket". CNN. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ https://spacenews.com/crypto-entrepreneur-to-go-to-space-on-new-shepard/

- ^ "Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin auctions off seat on first human spaceflight for $28M". TechCrunch. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ "Blue Origin sues U.S. government over SpaceX lunar lander contract". Reuters. August 16, 2021.

- ^ Doubek, James (August 21, 2021). "NASA Wants To Return To The Moon By 2024, But The Spacesuits Won't Be Ready". NPR. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ "Captain Kirk's space voyage with Blue Origin lands successfully".

- ^ "'Star Trek' actor William Shatner blasts off into space in Blue Origin launch". October 13, 2021.

- ^ Boyle, Alan. "Amazon.com billionaire's 5-ton flying jetpack lands in Seattle museum". NBC News. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ a b "Blue Origin Charon Test Vehicle". The Museum of Flight. Archived from the original on March 24, 2013. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ^ "Blue Origin's Original Charon Flying Vehicle Goes on Display at The Museum of Flight". The Museum of Flight. Archived from the original on March 28, 2013. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ^ "Blue Origin Charon Test Vehicle". Museum of Flight. Archived from the original on March 24, 2013. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- ^ Alan Boyle (November 28, 2006). "Blue Origin Rocket Report". cosmiclog.msnbc.msn.com. Archived from the original on April 15, 2008. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- ^ Alan Boyle (December 2, 2006). "Blue Alert For Blastoff". cosmiclog.msnbc.msn.com. Archived from the original on May 7, 2008. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- ^ "Launches". www.faa.gov. Archived from the original on April 21, 2019. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Blue Origin – About Blue". Archived from the original on March 25, 2013. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ^ [3] Archived May 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Blue Origin – Research". Archived from the original on April 13, 2013. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ^ "1/3552 NOTAM Details". Federal Aviation Administration. August 23, 2011. Retrieved August 23, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Bezos, Jeff (September 2, 2011). "Successful Short Hop, Set Back, and Next Vehicle". Letter. Blue Origin. Archived from the original on September 2, 2011. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Blue Origin Conducts Successful Pad Escape Test". Blue Origin. October 22, 2012. Archived from the original on December 15, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ "Bezos' Blue Origin completes first test flight of 'New Shepard' spacecraft". SpaceFlightNow. SpaceFlightNow. Archived from the original on April 7, 2019. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- ^ "Blue Origin Makes Historic Rocket Landing". Blue Origin. November 24, 2015. Archived from the original on November 25, 2015. Retrieved November 24, 2015.

- ^ a b c Amos, Jonathan (November 24, 2015). "New Shepard: Bezos claims success on second spaceship flight". BBC News. Archived from the original on July 13, 2018. Retrieved November 26, 2015.

- ^ Dillow, Clay. "Reporter". Fortune.com. Fortune.com. Archived from the original on January 28, 2016. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ Calandrelli, Emily. "Blue Origin releases video from third launch and landing of New Shepard". TechCrunch.com. Archived from the original on April 3, 2016. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ^ Grush, Loren (June 19, 2016). "Blue Origin safely launches and lands the New Shepard rocket for a fourth time". Archived from the original on July 30, 2017. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- ^ "New Shepard: Jeff Bezos' rocket tests Nasa Moon landing tech". BBC News. October 14, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ "Blue Origin's 1st upgraded New Shepard spacecraft for astronauts aces launch (and landing)". Space.com. January 15, 2021. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- ^ "Blue Origin succeeds in 15th New Shepard flight, critical test before carrying humans". NASA Spaceflight. April 14, 2021. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ https://spacenews.com/crypto-entrepreneur-to-go-to-space-on-new-shepard/

- ^ "New Glenn". Blue Origin. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ Jeff Bezos plans to boost humans into space from Cape Canaveral Archived August 22, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, CBS News, accessed September 17, 2015. Bezos: "You cannot afford to be a space-fairing civilization if you throw the rocket away every time you use it... We have to be focused on reusability, we have to be focused on lowering the cost of space".

- ^ "Blue Origin Completes Spacecraft System Requirements Review". Archived from the original on May 27, 2013. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ^ "Blue Origin tests 100k lb LOX/LH2 engine in commercial crew program". NewSpace Watch. October 16, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2012.

- ^ Samantha Masunaga (September 12, 2016). "Blue Origin's new, more powerful rocket will compete with SpaceX". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 17, 2016. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- ^ "Blue Origin releases details of its monster orbital rocket". March 7, 2017. Archived from the original on August 23, 2019. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ a b c Berger, Eric (July 27, 2021). "Blue Origin has a secret project named "Jarvis" to compete with SpaceX". Ars Technica. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- ^ a b Berger, Eric (August 24, 2021). "First images of Blue Origin's "Project Jarvis" test tank". Ars Technica. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ "Blue Origin and Sierra Space developing commercial space station". Blue Origin / News. Retrieved February 24, 2022.

- ^ https://www.orbitalreef.com

- ^ "BLUE ORIGIN OPENS UP". bt.e-ditionsbyfry.com. Retrieved May 6, 2021.

- ^ Berger, Eric (June 28, 2017). "Why is Jeff Bezos building rocket engines in Alabama? He's playing to win". Ars Technica. Retrieved May 6, 2021.

- ^ a b "Blue Origin Engines". Blue Origin. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ^ a b @jeff_foust (March 10, 2018). "Rob Meyerson shows this chart of the various engines Blue Origin has developed and the vehicle that have used, or will use, them. #spaceexploration" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Krebs, Gunter (April 29, 2018). "New Shepard". Gunter's Space Page. Archived from the original on May 16, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ^ a b c Messier, Doug (December 3, 2013). "Blue Origin Tests New Engine in Simulated Suborbital Mission Profile". Parabolic Arc. Archived from the original on December 6, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ "Updates on commercial crew development". NewSpace Journal. January 17, 2013. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- ^ a b Messier, Doug (December 3, 2013). "Video of Blue Origin Engine Test". Parabolic Arc. Archived from the original on December 6, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ Blue Origin Tests New Engine Archived January 8, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Aviation Week, 2013-12-09, accessed September 16, 2014.

- ^ a b c Ferster, Warren (September 17, 2014). "ULA To Invest in Blue Origin Engine as RD-180 Replacement". Space News. Archived from the original on September 18, 2014. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- ^ Neal, Mihir (June 8, 2020). "Vulcan on track as ULA eyes early-2021 test flight to the Moon". Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- ^ Wall, Mike. "SpaceX Falcon 9 Rocket Will Launch Private Moon Lander in 2021" Archived October 4, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Space.com. October 2, 2019. Quote: "But Peregrine will fly on a different rocket, United Launch Alliance's Vulcan Centaur, which is still in development. The 2021 Peregrine mission will be the first for both the lander and its launch vehicle".

- ^ Jeff Bezos unveils mock-up of Blue Origin's lunar lander Blue Moon Archived May 9, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Loren Grush, The Verge. May 9, 2019.

- ^ Blue Origin fires up the engine of its future Moon lander for the first timeArchived May 9, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Loren Grush, The Verge. June 20, 2019.

- ^ "BE-7". Archived from the original on May 11, 2019. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ^ "Aerojet Motor Plays Key Role in Successful Blue Origin Pad Escape". Aerojet Rocketdyne. Archived from the original on May 14, 2018. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- ^ "Aerojet Rocketdyne Motor Plays Key Role in Successful Blue Origin In-Flight Crew Escape Test". Aerojet Rocketdyne. Archived from the original on May 14, 2018. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- ^ a b Foust, Jeff (October 5, 2016). "Blue Origin successfully tests New Shepard abort system". SpaceNews. Retrieved October 5, 2016.

- ^ Stile, Marc (October 20, 2016). "Bezos' rocket company, Blue Origin, is the new owner of an old warehouse in Kent". bizjournals.com. Puget Sound Business Journal. Archived from the original on March 2, 2017. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ "Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin space venture has plans for big expansion of Seattle-area HQ". Geekwire.com. February 22, 2017. Archived from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved August 11, 2017.

- ^ "Blue Origin officially opens its new HQ and R&D center". TechCrunch. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ "Blue Origin takes one giant leap across the street to space venture's new HQ in Kent". GeekWire. January 6, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ "Blue Origin will build its rocket engine in Alabama because the space industry is ruled by politics". The Verge. Archived from the original on July 17, 2018. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ^ "Blue Origin opens rocket engine factory". SpaceNews. February 17, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ "Bezos' Blue Origin to build, launch rockets in Fla". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on July 17, 2018. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ^ Blue Origin's Rocket Factory Breaks Ground, June 2016, accessed Feb 2022

- ^ "Blue Origin". July 5, 2007. Archived from the original on July 5, 2007. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- ^ Graczyk, Michael (November 14, 2006). "Private space firm launches 1st test rocket". Associated Press. Archived from the original on January 7, 2007. Retrieved January 9, 2007.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (March 23, 2007). "Rocket Revelations". MSNBC. Archived from the original on January 19, 2008. Retrieved January 29, 2008.

- ^ "Recently Completed/Historical Launch Data". FAA AST. Archived from the original on March 11, 2008. Retrieved February 3, 2008.

- ^ "Recently Completed/Historical Launch Data". FAA AST. Archived from the original on March 11, 2008. Retrieved May 30, 2011.

- ^ a b "Blue Origin has a bad day (and so do some of the media)". Archived from the original on February 19, 2012. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- ^ Harwood, Bill (April 30, 2015). "Bezos' Blue Origin completes first test flight of 'New Shepard' spacecraft". Spaceflight Now via CBS News. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- ^ Pasztor, Andy (November 24, 2015). "Jeff Bezos's Blue Origin Succeeds in Landing Spent Rocket Back on Earth". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved November 24, 2015.

- ^ "Launch. Land. Repeat". Archived from the original on January 24, 2016. Retrieved January 23, 2016.

- ^ April 2016, Calla Cofield 04 (April 4, 2016). "Launch. Land. Repeat. Blue Origin's Amazing Rocket Liftoff & Landing in Pictures". Space.com. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ a b Boyle, Alan (June 19, 2016). "Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin live-streams its spaceship's risky test flight". GeekWire. Retrieved June 21, 2016.

- ^ "New Shepard In-flight Escape Test". Blue Origin. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ "Crew Capsule 2.0 First Flight". Blue Origin. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ "Blue Origin flies next-generation New Shepard vehicle". SpaceNews.com. December 13, 2017. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ "Apogee 351,000 Feet". Blue Origin. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ Clark, Stephen. "Video: Blue Origin flies New Shepard rocket for eighth time – Spaceflight Now".

- ^ a b Marcia Dunn (July 19, 2018). "Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin launches spacecraft higher than ever". Associated Press. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- ^ Clark, Stephen. "Blue Origin reschedules New Shepard launch for Wednesday – Spaceflight Now". Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ "Blue Origin New Shepard: Mission 10 (Q1 2019) – collectSPACE: Messages". www.collectspace.com. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ a b Clark, Stephen. "Blue Origin 'one step closer' to human flights after successful suborbital launch – Spaceflight Now". Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ^ a b "New Shepard sets reusability mark on latest suborbital spaceflight". SpaceNews.com. December 11, 2019. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (December 8, 2019). "Watch Blue Origin send thousands of postcards to space and back on test flight". Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ "New Shepard Mission NS-12 Updates". Blue Origin. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ "New Shepard Mission NS-13 Launch Updates". Blue Origin. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ "Blue Origin tests passenger accommodations on suborbital launch". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved January 14, 2021.

- ^ "Dress Rehearsal Puts Blue Origin Closer to Human Spaceflight". spacepolicyonline.com. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ Blue Origin [@blueorigin] (August 26, 2021). "Capsule, touchdown! A wholly successful payload mission for New Shepard. A huge congrats to the entire Blue Origin team on another successful flight" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "New Shepard Payload Mission NS-17 to Fly NASA Lunar Landing Experiment and Art Installation". Blue Origin. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Rocket fire of the vanities: Bezos space trip brings criticism from Earth-bound philanthropists

- ^ Erwin, Sandra (April 8, 2019). "Blue Origin urging Air Force to postpone launch competition". SpaceNews.com. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- ^ Erwin, Sandra (October 10, 2018). "Air Force awards launch vehicle development contracts to Blue Origin, Northrop Grumman, ULA". SpaceNews.com. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Blue Origin Space Act Agreement" (PDF). Nasa.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 22, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ a b Morring, Frank Jr. (April 22, 2011). "Five Vehicles Vie To Succeed Space Shuttle". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on December 21, 2011. Retrieved February 23, 2011.

the CCDev-2 awards...and went to Blue Origin, Boeing, Sierra Nevada Corp. and Space Exploration Technologies Inc. (SpaceX).

- ^ Foust, Jeff (February 25, 2021). "Blue Origin delays first launch of New Glenn to late 2022". Space News. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ^ "Blue Origin Space Act Agreement, Amendment One" (PDF). NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 22, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ "NASA Selects Commercial Firms to Begin Development of Crew Transportation Concepts and Technology Demonstrations for Human Spaceflight Using Recovery Act Funds". press release. NASA. February 1, 2010. Archived from the original on February 3, 2010. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- ^ Jeff Foust. "Blue Origin proposes orbital vehicle". Newspacejournal.com. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ [4] Archived June 10, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Commercial Crew Development (CCDev) Round One Companies Have Reached Substantial Hardware Milestones in Only 9 Months, New Images and Data Show" (PDF). Commercialspaceflight.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 21, 2012. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ "Blue Origin CCDev 2 Space Act Agreement" (PDF). Procurement.ksc.nasa.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 15, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ "NASA announces $1.1 billion in support for a trio of spaceships". Cosmicclog.nbcnews.com. Archived from the original on May 29, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ Matthews, Mark K. (August 18, 2013). "Musk, Bezos fight to win lease of iconic NASA launchpad". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on August 27, 2013. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ^ a b Messier, Doug (September 10, 2013). "Blue Origin Files Protest Over Lease on Pad 39A". Parabolic Arc. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013. Retrieved September 11, 2013.

- ^ a b Messier, Doug (December 12, 2013). "Blue Origin Loses GAO Appeal Over Pad 39A Bid Process". Parabolic Arc. Archived from the original on December 16, 2013. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (September 21, 2013). "A minor kerfuffle over LC-39A letters". Space Politics. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013. Retrieved September 25, 2013.

- ^ Dean, James (April 15, 2014). "With nod to history, SpaceX gets launch pad 39A OK". Florida Today. Archived from the original on July 30, 2014. Retrieved September 16, 2014.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (April 30, 2020). "NASA awards contracts to Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk to land astronauts on the moon". CNBC. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Christian, Davenport (April 30, 2020). "Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk win contracts for spacecraft to land NASA astronauts on the moon". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ "As Artemis Moves Forward, NASA Picks SpaceX to Land Next Americans on Moon". NASA Press Release. April 16, 2021. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ "Musk-Bezos Feud Intensifies: Blue Origin Protests NASA Choice of SpaceX Lunar Lander". Gizmodo. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ "Protest of Blue Origin Federation, LLC against National Aeronautics and Space Administration award of Option A contract for Human Landing System under Broad Agency Announcement NNH19ZCQ001K_APPENDIX-H-HLS" (PDF). Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ "Statement on Blue Origin-Dynetics Decision". U.S. Government Accountability Office. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- ^ "Bezos rocket engine selected for new Vulcan rocket". spaceflightnow.com. Archived from the original on September 29, 2018. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- ^ "MAC - "Space Travel Done Right"". MAC - "Space Travel Done Right". Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ "XS-1 Program to Ease Access to Space Enters Phase 2". Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. Archived from the original on May 21, 2016. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- ^ Giangreco, Leigh (February 25, 2020). "Space Force's Second-in-Command Explains What the Hell It Actually Does". Medium. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

Further reading[]

- Davenport, Christian. The Space Barons; Elon Musk. Jeff Bezos, and the Quest to Colonize the Cosmos. PublicAffairs (2018). ISBN 978-1610398299

- Fernholz, Tim. Rocket Billionaires: Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and the New Space Race. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (2018). ISBN 978-1328662231

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Blue Origin. |

- Official website

- Amazon Enters the Space Race Wired Magazine (July 2003)

- Amazon CEO gives us peek into space plans, a January 2005 article from The Seattle Times

- Amazon.com founder's space venture has West Texas county abuzz[permanent dead link] (Seattle Post-Intelligencer, March 12, 2005)

- Blue Origin West Texas Commercial Launch Site Environmental Assessment

- Latest Blue Origin News on the Space Fellowship

- Internet billionaires face off in renewed Texas space race, Brownsville Herald, April 2015.

Coordinates: 47°24′37″N 122°14′15″W / 47.41028°N 122.23750°W

- Blue Origin

- Private spaceflight companies

- Space tourism

- Aerospace companies of the United States

- Space Act Agreement companies

- Collier Trophy recipients

- Companies based in Kent, Washington

- Culberson County, Texas

- Technology companies established in 2000

- American companies established in 2000