New Shepard

New Shepard 2 (without capsule) at the 2017 EAA AirVenture | |

| Function | Suborbital launch vehicle |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Blue Origin |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Size | |

| Height | 18 m (59 ft) [1] |

| Stages | 1 |

| Launch history | |

| Status | Active |

| Launch sites | |

| Total launches | 17 |

| Success(es) | 16 |

| Failure(s) | 0 |

| Partial failure(s) | 1 |

| Other outcome(s) | 0 |

| Landings | 16 |

| First flight | 29 April 2015 |

| Last flight | 26 August 2021 |

| Single stage | |

| Engines | 1 BE-3 |

| Thrust | 490 kN (110,000 lbf) |

| Burn time | 141 seconds |

| Propellant | LH2 / LOX |

| Part of a series on |

| Private spaceflight |

|---|

| Active companies |

|

| Active vehicles |

|

| Contracts and programs |

|

|

New Shepard is a vertical-takeoff, vertical-landing (VTVL),[2] crew-rated suborbital launch vehicle developed by Blue Origin as a commercial system for suborbital space tourism.[3] Blue Origin is owned and led by Amazon founder and former CEO Jeff Bezos.

The name New Shepard makes reference to the first American astronaut in space, Alan Shepard, one of the original NASA Mercury Seven astronauts, who ascended to space in 1961 on a suborbital trajectory similar to that of New Shepard.[4]

Prototype engine and vehicle flights began in 2006, while full-scale engine development started in the early 2010s and was complete by 2015.[5] Uncrewed flight testing of the complete New Shepard vehicle (propulsion module and space capsule) began in 2015.

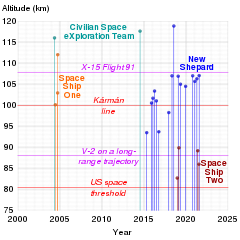

On 23 November 2015, after reaching 100.5 km (62.4 mi) altitude (outer space), the suborbital New Shepard booster successfully performed a powered vertical soft landing, the first time a suborbital booster rocket had returned from space to make a successful vertical landing.[6][7] The test program continued in 2016 and 2017 with four additional test flights made with the same vehicle (NS-2) in 2016 and the first test flight of the new NS-3 vehicle made in 2017.[8][9]

Blue Origin planned its first crewed test flight to occur in 2019, which was however delayed until 2021, and has since announced that tickets would begin to be sold for commercial flights of up to six people.[10][11][12] The first crewed flight took place on 20 July 2021. An anonymous buyer purchased one seat for the 20 July 2021 flight at auction for $28 million[13] but this person did not fly on said flight due to scheduling problems; the anonymous buyer was rescheduled for a later flight. Instead of the auction winning passenger, 18-year-old Oliver Daemen was selected to fly. Daemen's father paid for his flight, thus Daemen was the first customer (i.e. person whose flight has been paid for) passenger of New Shepard.

History[]

Early Blue Origin vehicle and engine development[]

The first development vehicle of the New Shepard development program was a sub-scale demonstration vehicle named Goddard, built in 2006 following earlier engine development efforts by Blue Origin. Goddard made its first flight on 13 November 2006.[14]

The Goddard launch vehicle was assembled at the Blue Origin facility near Seattle, Washington. Also in 2006, Blue Origin started the process to build an aerospace testing and operations center on a portion of the Corn Ranch, a 670 km2 (165,000 acres) land parcel Bezos purchased 40 km (25 mi) north of Van Horn, Texas.[15] Blue Origin Project Manager Rob Meyerson has said that they selected Texas as the launch site particularly because of the state's historical connections to the aerospace industry, although that industry is not located near the planned launch site, and the vehicle will not be manufactured in Texas.[16]

On the path to developing New Shepard, a crew capsule was also needed, and design was begun on a space capsule in the early 2000s. One development milestone along the way became public. On 19 October 2012, Blue Origin conducted a successful pad escape of a full-scale suborbital crew capsule at its West Texas launch site. For the test, the capsule fired its pusher escape motor and launched from a launch vehicle simulator. The Crew Capsule traveled to an altitude of 703 m (2,307 ft) under active thrust vector control before descending safely by parachute to a soft landing 500 m (1,630 ft) downrange.[17][18]

In April 2015, Blue Origin announced that they had completed acceptance testing of the BE-3 engine that would power the larger New Shepard vehicle. Blue also announced that they intended to begin flight testing of the New Shepard later in 2015, with initial flights occurring as frequently as monthly, with "a series of dozens of flights over the extent of the suborbital test program [taking] a couple of years to complete".[5] The same month, the FAA announced that the regulatory paperwork for the test program had already been filed and approved, and test flights were expected to begin before mid-May 2015.[19]

By February 2016, three New Shepard vehicles had been built. The first was lost in a test in April 2015, the second had flown twice (see below), and the third was completing manufacture at the Blue factory in Kent, Washington.

In 2016 the Blue Origin team were awarded the Collier Trophy for demonstrating rocket booster reusability with the New Shepard human spaceflight vehicle.[20]

Flight test program[]

A multi-year program of flight tests was begun in 2015[21] and continued into 2021.[22][11] By mid-2016, the test program was sufficiently advanced that Blue Origin began flying suborbital research payloads for universities and NASA.[23] The flight test program was completed in early 2021 and the first flight carrying passengers to suborbital space occurred in July 2021.[24]

New Shepard 1[]

The first flight of the full-scale New Shepard vehicle — NS1[25] — was conducted on 29 April 2015 during which an altitude of 93.5 km (58.1 mi) was attained. While the test flight itself was deemed a success, and the capsule was successfully recovered via parachute landing, the booster crash landed and was not recovered due to a failure of hydraulic pressure in the vehicle control system during descent.[26][27]

New Shepard 2[]

The New Shepard 2 (NS2) flight test article propulsion module made five successful flights in 2015 and 2016, being retired after its fifth flight in October 2016.

First vertical soft landing[]

After the loss of NS1, a second New Shepard vehicle was built, NS2. Its first flight,[25] and the second test flight of New Shepard overall, was carried out on 23 November 2015, reaching 100.5 km (62.4 mi) altitude with successful recovery of both capsule and booster stage.[6][7] The booster rocket successfully performed a powered vertical landing.[7] This was the first such successful rocket vertical landing on Earth after travelling higher than 3.140 km (1.951 mi) that the McDonnell Douglas DC-XA achieved in the 1990s, and first after sending something into space. Jeff Bezos was quoted as saying that Blue Origin planned to use the same architecture of New Shepard for the booster stage of their orbital vehicle.[28]

Second vertical soft landing[]

On 22 January 2016, Blue Origin successfully repeated the flight profile of 23 November 2015 launch with the same New Shepard vehicle. New Shepard launched, reached a maximum altitude of 101.7 km (63.2 mi), and, after separation, both capsule and launch vehicle returned to the ground intact. This accomplishment demonstrated re-usability of New Shepard and a turnaround time of 61 days.[29][30]

Third vertical soft landing[]

On 2 April 2016, the same New Shepard booster flew for a third time, reaching 103.381 km (64.2383 mi), before returning successfully.[31]

Fourth vertical soft landing[]

On 19 June 2016, the same New Shepard booster flew, now for a fourth time, again reaching over 100 km (63 mi), before returning successfully for a VTVL rocket-powered landing.[32]

The capsule returned once again under parachutes but, this time, did a test descent with only two parachutes before finishing with a brief pulse of retro rocket propulsion to slow the ground impact velocity to 4.8 km/h (3 mph). The two parachutes "slowed the descent to 23 mph, as opposed to the usual 16 mph with three parachutes". Crushable bumpers are used to further reduce the landing shock through energy-absorbing deformation.[33]

Fifth and final flight test[]

A fifth and final test flight of the NS2 propulsion module was conducted on 5 October 2016.[34] The principal objective was to boost the passenger module to the point of highest dynamic pressure at transonic velocity and conduct a flight test of the in-flight abort system. Due to subsequent buffet and forces that impact the propulsion module after the high-velocity separation of the passenger capsule that are outside the design region of the PM, NS2 was not expected to survive and land, and if it did, Blue had stated that NS2 would be retired and become a museum item.[8] In the event, the flight test was successful. The abort occurred, and NS2 remained stable after the capsule abort test, completed its ascent to space, and successfully landed for a fifth and final time.[34]

New Shepard 3[]

New Shepard 3 (NS3), also known as RSS H. G. Wells after the author,[35] was modified for increased reusability and improved thermal protection; it includes a redesigned propulsion module and the inclusion of new access panels for more rapid servicing and improved thermal protection. NS3 is the third propulsion module built. It was completed and shipped to the launch site by September 2017,[36] although parts of it had been built as early as March 2016.[25] Flight tests began in 2017 and continued into 2019.[11] The new Crew Capsule 2.0, featuring windows, is integrated to the NS3.[36] NS3 will only ever be used to fly cargo; no passengers will be carried.[37]

Its initial flight test occurred on 12 December 2017.[9] This was the first flight flown under the regulatory regime of a launch license granted by the US Federal Aviation Administration. Previous test flights had flown under an experimental permit, which did not allow Blue to carry cargo for which it is paid for commercially. This made the flight of NS3 the first revenue flight for payloads, and it carried 12 experiments on the flight, as well as a test dummy given the moniker "Mannequin Skywalker."[38]

Since the maiden flight, "Blue Origin has been making updates to the vehicle ... intended primarily to improve operability rather than performance or reliability. Those upgrades took longer than expected" leading to a several-month gap in test flights.[11] The second test flight took place on 29 April 2018.[39] The 10th overall New Shepard flight, and the fourth NS3 flight, had originally been planned for December 2018, but was delayed due to "ground infrastructure issues." Following a diagnostics of the initial issue, Blue rescheduled the launch for early 2019, after discovering "additional systems" that needed repairs as well.[40] The flight launched on 23 January 2019 and successfully flew to space with a maximum altitude of 106.9 km (66.4 mi).[41] It has been used to test SPLICE ("Safe and Precise Landing – Integrated Capabilities Evolution"), a NASA lunar landing technology demonstration, on two separate flights in October 2020 (NS-13) and August 2021 (NS-17).[42]

New Shepard 4[]

New Shepard 4 (NS4), also known as RSS First Step, was the fourth propulsion module to be built and the first to carry human passengers. Bezos himself was a passenger.[43] The vehicle was manufactured in 2018 and moved to the Texas Blue Origin West Texas launch facility in December 2019.[44] The uncrewed maiden launch of NS4 occurred on January 14, 2021.[45] The New Shepard 4, with four passengers, was successfully launched on July 20, 2021.

Commercial flights[]

For many years, Blue Origin did not make any public statements about the date of the start of commercial flights of New Shepard. But this changed in June 2018 when the company announced that while it continued to plan to fly initial internal passengers later in 2018, it would not be selling commercial tickets for New Shepard until 2019[12] but the first commercial flight was delayed until 2021.[46]

Blue Origin commenced the first flight carrying passengers on the 16th flight of New Shepard (NS-16) on 20 July 2021.[46] One commercial seat was auctioned on 12 June 2021 for US$28 million which will go to Blue Origin’s foundation, Club for the Future, which inspires future generations to pursue careers in STEM. However, due to scheduling problems, the $28M auction winner did not participate in the NS-16 flight. The $28M auction winner was rescheduled to fly at a later flight. The astronauts aboard the NS-16 flight on 20 July 2021 were Jeff Bezos, Mark Bezos, Wally Funk and Oliver Daemen. At 82 years old Funk was the oldest person, and at 18 Daeman was the youngest, to travel into space.[47][13][48] Daemen got the commercial seat that the $28M auction winner did not use. Daemen's flight was paid for by his father, thus making Daemen the first commercial passenger of New Shepard.

Full flight list[]

| Launch No. | Date | Vehicle | Apogee | Outcome | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | 19 October 2012 | N/A | 0.7 km (0.4369 mi) | Success | Pad abort test of the New Shepard crew capsule. |

| 1 | 29 April 2015 | NS1 | 93.5 km (58.1 mi) | Partial success | Flight to altitude 93.5 km, capsule recovered, booster crashed on landing.[49] |

| 2 | 23 November 2015 | NS2.1 | 100.535 km (62.4695 mi)[7] | Success | Sub-orbital spaceflight and landing.[50] |

| 3 | 22 January 2016 | NS2.2 ♺ | 101.676 km (63.1784 mi)[30] | Success | Sub-orbital spaceflight and landing of a reused booster.[51] |

| 4 | 2 April 2016 | NS2.3 ♺ | 103.381 km (64.2383 mi)[52] | Success | Sub-orbital spaceflight and landing of a reused booster.[31] |

| 5 | 19 June 2016 | NS2.4 ♺ | 101.042 km (62.7843 mi)[53] | Success | Sub-orbital spaceflight and landing of a reused booster: the fourth launch and landing of the same rocket. Blue Origin published a live webcast of the takeoff and landing.[53] |

| 6 | 5 October 2016 | NS2.5 ♺ | Booster: 93.713 km (58.2307 mi)

Capsule: 7.092 km (4.4070 mi)[54] |

Success | Sub-orbital spaceflight and landing of a reused booster. Successful test of the in-flight abort system. The fifth and final launch and landing of the same rocket (NS2).[34] |

| 7 | 12 December 2017 | NS3.1 | Booster: 98.155 km (60.9909 mi)

Capsule: 98.269 km (61.0616 mi)[55] |

Success | Flight to just under 100 km and landing. The first launch of NS3 and a new Crew Capsule 2.0.[56] |

| 8 | 29 April 2018 | NS3.2 ♺ | 107 km (66.5 mi)[57] | Success | Sub-orbital spaceflight and landing of a reused booster.[39] |

| 9 | 18 July 2018 | NS3.3 ♺ | 118.825 km (73.8345 mi)[35] | Success | Sub-orbital spaceflight and landing of a reused booster, with the Crew Capsule 2.0-1 RSS H.G.Wells, carrying a mannequin. Successful test of the in-flight abort system at high altitude. Flight duration was 11 minutes.[35] |

| 10 | 23 January 2019 | NS3.4 ♺ | c. 106.9 km (66.4 mi)[41] | Success | Sub-orbital flight, delayed from 18 December 2018. Eight NASA research and technology payloads were flown.[58][59] |

| 11 | 2 May 2019 | NS3.5 ♺ | c. 105 km (65.5 mi)[60] | Success | Sub-orbital flight. Maximum Ascent Velocity: 3,568 km/h (2,217 mph),[60] duration: 10 minutes, 10 seconds. Payload: 38 microgravity research payloads (nine sponsored by NASA). |

| 12 | 11 December 2019 | NS3.6 ♺ | c. 104.5 km (64.9 mi)[61] | Success | Sub-orbital flight, Payload: Multiple commercial, research (8 sponsored by NASA) and educational payloads, including postcards from Club for the Future.[62][63] The sixth launch and landing of the same rocket.[61] |

| 13 | 13 October 2020, 13:37 | NS3.7 ♺ | c. 107.0 km (66.52 mi) | Success | 7th flight of the same capsule/booster. Onboard 12 payloads include Space Lab Technologies, Southwest Research Institute, postcards and seeds for Club for the Future, and multiple payloads for NASA including SPLICE to test future lunar landing technologies in support of the Artemis program.[64] |

| 14 | 14 January 2021, 16:57 [65] | NS4.1 | Booster: 106.942 km (66.4504 mi)

Capsule: 107.050 km (66.5180 mi) |

Success | Uncrewed qualification flight for NS4 rocket and capsule and maiden flight for NS4 |

| 15 | 14 April 2021 16:51[66][67] |

NS4.2 ♺ | Booster: 105.671 km (65.6612 mi)

Capsule: 106.300 km (66.0517 mi) |

Success | Second flight of NS4, first preflight human passenger process test where Blue Origin conducted an "Astronaut Rehearsal." Gary Lai, Susan Knapp, Clay Mowry, and Audrey Powers, all Blue Origin personnel, were “stand-in astronauts”. Lai and Powers briefly entered the capsule during the test.[22] |

| 16 | 20 July 2021 13:12[68][69] |

NS4.3 ♺ | Booster: 105.823 km (65.7553 mi)

Capsule: 107.05 km (66.517 mi) |

Success | First human flight of New Shepard, with four passengers:[24] * Jeff Bezos[70] * Mark Bezos * Wally Funk[48] * Oliver Daemen |

| 17 | 25 August 2021 14:31[71] |

NS3.8 ♺ | Booster: 105.775 km (65.7258 mi)

Capsule: 105.898 km (65.8019 mi) |

Success | Payload mission consisting of 18 commercial payloads inside the crew capsule, a NASA lunar landing technology demonstration installed on the exterior of the booster and an art installation installed on the exterior of the crew capsule.[72] |

Design[]

The New Shepard is a fully reusable, vertical takeoff, vertical landing (VTVL) space vehicle composed of two principal parts: a pressurized crew capsule and a booster rocket that Blue Origin calls a propulsion module.[27] The New Shepard is controlled entirely by on-board computers, without ground control[5] or a human pilot.[21]

Crew capsule[]

The New Shepard Crew Capsule is a pressurized crew capsule that can carry six people, and supports a "full-envelope" launch escape system that can separate the capsule from the booster rocket anywhere during the ascent.[73] Interior volume of the capsule is 15 cubic meters (530 cu ft).[74] The Crew Capsule Escape Solid Rocket Motor (CCE-SRM) is sourced from Aerojet Rocketdyne.[75] After separation two or three parachutes deploy. Just before landing, retro rockets fire. (see Fourth vertical soft landing (19 June 2016) above)

Propulsion module[]

The New Shepard propulsion module is powered using a Blue Origin BE-3 bipropellant rocket engine burning liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen,[5] although some early development work was done by Blue Origin on engines operating with other propellants: the BE-1 engine using monopropellant hydrogen peroxide; and the BE-2 engine using high-test peroxide oxidizer and RP-1 kerosene fuel.[76][77]

Flight profile[]

The New Shepard is launched vertically from West Texas and then performs a powered flight for about 110 s and to an altitude of 40 km (25 mi). The craft's momentum carries it upward in unpowered flight as the vehicle slows, culminating at an altitude of about 100 km (62 mi). After reaching apogee the vehicle performs a descent and restart its main engines a few tens of seconds before vertical landing, close to its launch site.[78][better source needed] The total flight duration is planned to be 10 minutes.

The crewed variant features a separate crew module that separates close to peak altitude, and the propulsion module performs a powered landing while the crew module lands under parachutes. The crew module can also separate in case of vehicle malfunction or other emergency using solid propellant separation boosters and perform a parachute landing.[21][better source needed]

Development[]

Initial low altitude flight testing (up to 600 m (2,000 ft)) with subscale prototypes of the New Shepard was scheduled for the fourth quarter of 2006.[16] This was later confirmed to have occurred in November 2006 in a press release by Blue Origin.[14] The prototype flight test program could involve up to ten flights. Incremental flight testing to 100 km altitude was planned to be carried out between 2007 and 2009 with increasingly larger and more capable prototypes. The full-scale vehicle was initially expected to be operational for revenue service as early as 2010,[16] though that goal was not met and the first full-scale test flight of a New Shepard vehicle was successfully completed 2015, with commercial service currently aimed for no earlier than 2020.[79] The vehicle could fly up to 50 times a year. Clearance from the FAA was needed before test flights began, and a separate license is needed before commercial operations begin. Blue held a public meeting on 15 June 2006 in Van Horn, as part of the public comment opportunity needed to secure FAA permissions.[16] Blue Origin projected in 2006 that once cleared for commercial operation, they would expect to conduct a maximum rate of 52 launches per year from West Texas. The RLV would carry three or more passengers per operation.[80]

Prototype test vehicle[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (April 2015) |

An initial flight test of a prototype vehicle took place on 13 November 2006 at 6:30 am local time (12:30 UTC);[81][82][83] an earlier flight on the 10th being canceled due to winds. This marked the first developmental test flight undertaken by Blue Origin. The flight was by the first prototype vehicle, known as Goddard.[84] The flight to 87 metres (285 ft) in altitude was successful. Videos are available on the Blue Origin website[85] and elsewhere.

Second test vehicle[]

A second test vehicle made two flights in 2011. The first flight was a short hop (low altitude, VTVL takeoff and landing mission) flown on 6 May 2011. The vehicle is known only as "PM2" as of August 2011, gleaned from information the company filed with the FAA prior to its late August high-altitude, high-velocity second test flight. Media have speculated this might mean "Propulsion Module".[86]

This vehicle was flown a second time[84] on a 24 August 2011 test flight, in west Texas. It failed when ground personnel lost contact and control of the vehicle. The company recovered remnants of the craft from ground search.[87] On 2 September 2011, Blue Origin released the results of the cause of the test vehicle failure. As the vehicle reached Mach 1.2 and 14 kilometres (8.5 mi) altitude, a "flight instability drove an angle of attack that triggered [the] range safety system to terminate thrust on the vehicle."[84]

Involvement with NASA Commercial Crew Development Program[]

Additionally, Blue Origin received US$3.7 million in Commercial Crew Development (CCDev) phase 1 to advance several development objectives of its innovative "pusher" Launch Abort System (LAS) and composite pressure vessel.[88]

As of February 2011, with the end of the second ground test, Blue Origin completed all work envisioned under the phase 1 contract for the pusher escape system. They also "completed work on the other aspect of its award, risk reduction work on a composite pressure vessel" for the vehicle.[89]

Commercial suborbital flights[]

Passenger flights[]

Following the fifth and final test flight of the NS2 booster and test capsule in October 2016, Blue Origin indicated that they were on track for flying test astronauts by the end of 2017, and beginning commercial suborbital passenger flights in 2018.[90] After fifteen test flights, the company flew its first 4 passengers—Wally Funk, Jeff Bezos, Mark Bezos, and Oliver Daemon—on Blue Origin NS-16.[91][67][13]

NASA suborbital research payloads[]

As of March 2011, Blue Origin had submitted the New Shepard reusable launch vehicle for use as an uncrewed rocket for NASA's suborbital reusable launch vehicle (sRLV) solicitation under NASA's Flight Opportunities Program. Blue Origin projects 100 km (62 mi) altitude in flights of approximately ten minutes duration, while carrying an 11.3 kg (25 lb) research payload.[2] By March 2016, Blue noted that they are "due to start flying unaccompanied scientific payloads later [in 2016]."[21]

See also[]

- McDonnell Douglas DC-X – Prototype single-stage-to-orbit rocket, 1990s

- Lunar Lander Challenge

- Armadillo Mod 2009

- Masten Xoie

- New Glenn

- SpaceShipTwo – Suborbital spaceplane for space tourism

- SpaceX reusable launch system development program

- List of crewed spacecraft

References[]

- ^ https://www.space.com/40372-new-shepard-rocket.html

- ^ Jump up to: a b "sRLV platforms compared". NASA. 7 March 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

New Shepard: Type: VTVL/Unpiloted

- ^ Doug Mohney (7 May 2015). "Will Jeff Bezos Speed Past Virgin Galactic to Tourist Space?". TechZone360.

- ^ Jonathan Amos (30 April 2015). "Jeff Bezos conducts New Shepard flight". BBC.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Foust, Jeff (13 April 2015). "Blue Origin's suborbital plans are finally ready for flight". Retrieved 18 April 2015.

We've recently completed acceptance testing, meaning we've accepted the engine for suborbital flight on our New Shepard vehicle, [the end of a] very, very long development program [of] 450 test firings of the engine and a cumulative run time of more than 500 minutes. The completion of those tests sets the stage for Blue Origin to begin test flights of the vehicle later this year at its facility in West Texas [where they] expect a series of flight tests with this vehicle ... flying in autonomous mode... We expect a series of dozens of flights over the extent of the test program [taking] a couple of years to complete.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Blue Origin Makes Historic Rocket Landing". Blue Origin. 24 November 2015. Archived from the original on 25 November 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Amos, Jonathan (24 November 2015). "New Shepard: Bezos claims success on second spaceship flight". BBC News. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Blue Origin plans next New Shepard test for October – SpaceNews.com". 8 September 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Jeff Bezos says Blue Origin gives test dummy 'a great ride' on New Shepard suborbital spaceship". GeekWire. 13 December 2017. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ [1] Chris Bergin, NASASpaceflight.com, 28 November 2018

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Foust, Jeff (19 April 2018). "Blue Origin expects BE-4 qualification tests to be done by year's end". SpaceNews. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Foust, Jeff (21 June 2018). "Blue Origin plans to start selling suborbital spaceflight tickets by next year". SpaceNews. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "$28M is winning bid for seat aboard Blue Origin's 1st human space flight". ABC News. 12 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Blue Origin Flight Test Update". SpaceFellowship. 2 January 2007.

Our first objective is developing New Shepard, a vertical take-off, vertical-landing vehicle designed to take a small number of astronauts on a sub-orbital journey into space. On the morning of 13 November 2006, we launched and landed Goddard – a first development vehicle in the New Shepard program.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (13 January 2006). "Amazon founder unveils space center plans". NBC News. Retrieved 28 June 2006.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d David, Leonard (15 June 2006). "Public Meeting Details Blue Origin Rocket Plans". Space.com. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ Lindsay, Clark (22 October 2012). "Blue Origin carries out crew capsule pad escape test". NewSpace Watch. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ Foust, Jeff (21 April 2015). "Blue Origin To Begin Test Flights Within Weeks". Space news. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ Berry, Stephanie (29 March 2017). "Blue Origin New Shepard to Receive the 2016 Robert J. Collier Trophy" (PDF). NAA. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Boyle, Alan (5 March 2016). "Jeff Bezos lifts curtain on Blue Origin rocket factory, lays out grand plan for space travel that spans hundreds of years". GeekWire. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Smith, Marcia (14 January 2021). "Dress Rehearsal Puts Blue Origin Closer to Human Spaceflight". spacepolicyonline.com. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ David, Leonard (12 August 2016). "Blue Origin's Sweet Spot: An Untapped Suborbital Market for Private Spaceflight". Space.com. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Winning Ticket to Join Jeff Bezos in Space Costs Nearly $30 Million in Blue Origin Auction". Wall Street Journal. 12 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Berger, Eric (9 March 2016). "Behind the curtain: Ars goes inside Blue Origin's secretive rocket factory". Ars Technica. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ Bezos, Jeff (27 April 2015). "First Developmental Test Flight of New Shepard". Blue Origin. Archived from the original on 30 April 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Foust, Jeff (30 April 2015). "Blue Origin's New Shepard Vehicle Makes First Test Flight". Space News. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (24 November 2015). "Blue Origin Flies — and Lands — New Shepard Suborbital Spacecraft". Space News. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

We’re going to take that same exact architecture that was demonstrated and use it on our the booster stage of our orbital vehicle

- ^ Foust, Jeff (23 January 2016). "Blue Origin reflies New Shepard suborbital vehicle". SpaceNews. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Berger, Brian (23 January 2016). "Launch. Land. Repeat: Blue Origin posts video of New Shepard's Friday flight". SpaceNews. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Calandrelli, Emily (2 April 2016). "Blue Origin launches and lands the same rocket for a third time". Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ^ Grush, Loren (19 June 2016). "Blue Origin safely launches and lands the New Shepard rocket for a fourth time". Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (20 July 2016). "Jeff Bezos touts results from Blue Origin spaceship's test, even with one less chute". GeekWire. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Foust, Jeff (5 October 2016). "Blue Origin successfully tests New Shepard abort system". SpaceNews. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Marcia Dunn (19 July 2018). "Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin launches spacecraft higher than ever". Associated Press. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Blue Origin enlarges New Glenn’s payload fairing, preparing to debut upgraded New Shepard, Caleb Henry, SpaceNews, accessed 15 September 2017.

- ^ first time we've had two rockets in the barn in West Texas, Blue Origin, 17 December 2018, accessed 26 December 2018.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (19 December 2017). "Blue Origin a year away from crewed New Shepard flights". SpaceNews. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Clark, Stephen (29 April 2018). "Video: Blue Origin flies New Shepard rocket for eighth time". Spaceflight Now.

- ^ Bartels, Meghan (20 December 2019). "Blue Origin Delays Next New Shepard Launch to Early 2019". Space.com. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b New Shepard makes 10th launch as Blue Origin aims to fly humans late in 2019. Eric Berger, Ars Technica. 23 January 2019, accessed 26 January 2019.

- ^ Newton, Laura (24 August 2021). "NASA Technologies Slated for Testing on Blue Origin's New Shepard". NASA. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ Jackie Wattles. "Jeff Bezos is going to space". CNN. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ Wall, Mike (4 October 2019). "Blue Origin Probably Won't Launch People to Space This Year". space.com. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ Burghardt, Thomas (14 January 2021). "Blue Origin tests New Shepard capsule upgrades on NS-14 mission". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Foust, Jeff (20 July 2021). "Blue Origin launches Bezos on first crewed New Shepard flight". SpaceNews. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ https://www.space.com/blue-origin-18-year-old-passenger-identity-revealed

- ^ Jump up to: a b Blue Origin [@blueorigin] (1 July 2021). "Welcome aboard, Wally. Here's the moment Jeff Bezos asked Wally Funk to join our first human flight on July 20 as our honored guest" (Tweet). Retrieved 1 July 2021 – via Twitter.

- ^ Harwood, Bill (30 April 2015). "Bezos' Blue Origin completes first test flight of "New Shepard" spacecraft". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ^ Pasztor, Andy (24 November 2015). "Jeff Bezos's Blue Origin Succeeds in Landing Spent Rocket Back on Earth". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ^ "Launch Land Repeat". Archived from the original on 24 January 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ April 2016, Calla Cofield 04. "Launch Land Repeat Blue Origin's Amazing Rocket Liftoff and Landing in Pictures". space.com. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Boyle, Alan (19 June 2016). "Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin live-streams its spaceship's risky test flight". GeekWire. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ^ "New Shepard In-flight Escape Test". Blue Origin. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ "Crew Capsule 2.0 First Flight". Blue Origin. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ "Blue Origin flies next-generation New Shepard vehicle". SpaceNews.com. 13 December 2017. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ "Apogee 351,000 Feet". Blue Origin. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ Clark, Stephen. "Blue Origin reschedules New Shepard launch for Wednesday". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ^ "Blue Origin New Shepard: Mission 10 (Q1 2019) - collectSPACE: Messages". www.collectspace.com. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Clark, Stephen. "Blue Origin "one step closer" to human flights after successful suborbital launch". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "New Shepard sets reusability mark on latest suborbital spaceflight". SpaceNews.com. 11 December 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (8 December 2019). "Watch Blue Origin send thousands of postcards to space and back on test flight". Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ "New Shepard Mission NS-12 Updates". Blue Origin. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (13 October 2020). "Blue Origin launches and lands the 13th test flight of its space tourism rocket New Shepard". CNBC. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ "FCC APPLICATION FOR SPECIAL TEMPORARY AUTHORITY".

- ^ "NS-15 (Suborbital)". RocketLaunch.live. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin launches and lands rocket New Shepard, as it prepares to launch people". 14 April 2021.

- ^ "Bid for the very first seat on New Shepard". blueorigin.com. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ "WATCH LIVE: First Human Flight (NS-16, Suborbital) Mission (New Shepard) - RocketLaunch.Live". www.rocketlaunch.live. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ Bezos, Jeff [@jeffbezos] (7 June 2021). "Ever since I was five years old, I've dreamed of traveling to space. On July 20th, I will take that journey with my brother. The greatest adventure, with my best friend. #GradatimFerociter" – via Instagram.

- ^ Blue Origin [@blueorigin] (26 August 2021). "Capsule, touchdown! A wholly successful payload mission for New Shepard. A huge congrats to the entire Blue Origin team on another successful flight" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "New Shepard Payload Mission NS-17 to Fly NASA Lunar Landing Experiment and Art Installation". Blue Origin. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ Blue Origin. The New Shepard Crew Capsule. YouTube. Archived from the original on 25 July 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ "Our Approach to Technology". Blue Origin. Blue Origin. Archived from the original on 10 January 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

The system consists of a pressurized capsule atop a booster. The combined vehicles launch vertically, accelerating for approximately two and a half minutes, before the engine cuts off. The capsule then separates from the booster to coast quietly into space. After a few minutes of free fall, the booster performs an autonomously controlled rocket-powered vertical landing, while the capsule lands softly under parachutes, both ready to be used again. Reusability allows us to fly the system again and again. ... The New Shepard capsule’s interior is ... 530 cubic feet—offering over 10 times the room Alan Shepard had on his Mercury flight. It seats six astronauts. Three independent parachutes [on the capsule] provide redundancy, while a retro-thrust system further cushions [the] landing. ... Full-envelope escape [system] is built around a solid rocket motor that provides 70,000 lb. of thrust in a two-second burn.

- ^ "Aerojet Rocketdyne Motor Plays Key Role in Successful Blue Origin In-Flight Crew Escape Test". SpaceRef.com. 6 October 2016.

- ^ Blue Origin, "Our Approach to Technology" Archived 10 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ^ Morring, Frank Jr., "Blue Origin Developing Its Own Launch Vehicle", Aerospace Daily & Defense Report, 30 April 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ^ [3] Archived 15 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Foust, Jeff (5 March 2016). "Blue Origin plans growth spurt this year". SpaceNews. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ David, Leonard (13 June 2005). "Blue Origin: Rocket plans spotlighted". Space.com. Retrieved 28 June 2006.

- ^ Sigurd De Keyser (14 November 2006). "Blue Origin: Launches test rocket". spacefellowship.com. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ AP (14 November 2006). "Private Texas spaceport launches test rocket". eastlandspin.com. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ AP (14 November 2006). "Amazon Founder's Private Spaceport Launches First Rocket". foxnews.com. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bezos, Jeff (2 September 2011). "Successful Short Hop, Set Back, and Next Vehicle". Letter. Blue Origin. Archived from the original on 2 September 2011. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- ^ [4] Archived 16 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Blue Origin has a bad day (and so do some of the media)". NewSpace Journal. 2 September 2011. Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- ^ "Bezos-Funded Spaceship Misfires". Wall Street Journal. 2 September 2011. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- ^ Jeff Foust. "Blue Origin proposes orbital vehicle". NewSpace Journal. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ "CCDev awardees one year later: where are they now?". NewSpace Journal. 4 February 2011. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (14 October 2016). "Blue Origin on track for human suborbital test flights in 2017". SpaceNews. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

We’re still on track to flying people, our test astronauts, by the end of 2017, and then starting commercial flights in 2018.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (14 January 2021). "Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin aims to fly first passengers on its space tourism rocket as early as April". CNBC. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to New Shepard. |

- Official website

- Blue's Rocket Clues (MSNBC's Cosmic Log, 24 June 2006)

- Future & Fantasy Spaceships Primed for Launch Commercial, Orbital Spacecraft (See Page 8)

- Latest Blue Origin news on the Space Fellowship

- Secretive Spaceship Builder's Plans Hinted at in NASA Agreement Commercial Crew Development Blue Origin (2 New craft images)

- Videos

- Images and videos at Blue Origin

- New Shepard space vehicle first successful soft landing, 23 November 2015 (YouTube).

- Blue Origin launch vehicles

- Space tourism

- Private spaceflight

- Reusable launch systems

- VTVL rockets

- Suborbital spaceflight

- Vehicles introduced in 2015

- Alan Shepard