Office of Film and Literature Classification

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2020) |

| Te Tari Whakarōpū Tukuata, Tuhituhinga | |

Logo as of 2020 | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 1 October 1994 |

| Preceding agencies |

|

| Type | Crown entity |

| Jurisdiction | Government of New Zealand |

| Headquarters | Level 1 88 The Terrace Wellington, New Zealand 41°16′55″S 174°46′29″E / 41.28194°S 174.77472°ECoordinates: 41°16′55″S 174°46′29″E / 41.28194°S 174.77472°E |

| Motto | Watch carefully. Think critically. |

| Employees | 24 |

| Annual budget | $2,601,000 NZD (2019)[1] |

| Minister responsible |

|

| Agency executives |

|

| Key document | |

| Website | www |

The Office of Film and Literature Classification (OFLC, Māori: Te Tari Whakarōpū Tukuata, Tuhituhinga) is an independent Crown entity established under Films, Videos, and Publications Classification Act 1993 responsible for censorship and classification of publications in New Zealand. A "publication" is defined broadly to be any thing that shows an image, representation, sign, statement, or word.[2] This includes films, video games, books, magazines, CDs,[3] T-shirts, street signs, jigsaw puzzles, drink cans, and campervans.[4][5][6] The chairperson of the OFLC is the Chief Censor, a position that is selected by the Governor-General on the recommendation of the Minister of Internal Affairs with the agreement of the Minister of Women's Affairs and the Minister of Justice.[7] As of 8 May 2017, the current Chief Censor is David Shanks.

Films must be given a classification before they can be exhibited or supplied to the public. This is done either by the Film and Video Labelling Body or the OFLC.[citation needed]

The Chief Censor has the power to "call in" publications that have not come to the Office.

Any person may submit any publication for classification by the OFLC, with the permission of the Chief Censor. However, the Secretary for Internal Affairs, the Comptroller of Customs, the Commissioner of Police, and the Film and Video Labelling Body may submit publications for classification without the Chief Censor's permission. The courts have no jurisdiction to classify publications. If the classification of a publication becomes an issue in any civil or criminal proceeding, the court must submit the publication to the OFLC.

Any person who is dissatisfied with a decision of the OFLC may have the relevant publication, but not the OFLC's decision, reviewed by the Film and Literature Board of Review.

The Office also has a role in providing information to the public about classification decisions and about the classification system as a whole. It conducts research and produces evidence-based resources to promote media literacy and help people to make informed choices about the content they consume.[citation needed]

Labels[]

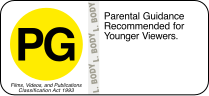

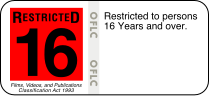

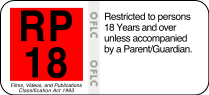

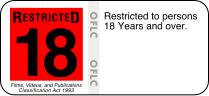

The FVPC Act gives the OFLC the power to classify publications into three categories: unrestricted, restricted, and "objectionable" or banned. Unrestricted films are assigned a green or yellow rating label. Restricted films are assigned a red classification label.

Since early 2013 some DVDs and Blu-rays released in New Zealand have had the rating label printed on the cover to prevent the removal of the label, which is illegal.

New Zealand has used a colour-coded labelling system since 1987. The colours are intended to resemble the messages conveyed by a traffic light: a green label means that nothing in the film, video or DVD should inhibit anyone from viewing it; a yellow label means proceed with caution because the film, video or DVD may have content that younger viewers should not see; and a red label means stop and ensure that no one outside the restriction views the film, video, DVD or computer game. It is an offence to supply age-restricted material to anyone under the age shown on the label.

The current classification system was introduced in 1993, harmonising the previously different standards for film and video. The following classifications are currently in use:

| Label | Name | Definition |

|---|---|---|

|

General | Suitable for general audiences. |

|

Parental Guidance | Parental guidance recommended for younger viewers. |

|

Mature | Suitable for (but not restricted to) mature audiences 16 years and up. |

|

RP13 | Restricted to people 13 years of age and over, unless accompanied by a parent or guardian. |

|

R13 | Restricted to people 13 years of age and over. |

|

R15 | Restricted to people 15 years of age and over. |

|

RP16 | Restricted to people 16 years of age and over, unless accompanied by a parent or guardian. |

|

R16 | Restricted to people 16 years of age and over. |

|

RP18 | Restricted to people 18 years of age and over unless accompanied by a parent or guardian. |

|

R18 | Restricted to people 18 years of age and over. |

|

Restricted | Restricted to a particular class of people, or for particular purposes, or both, specified by the Office of Film and Literature Classification. |

The RP18 rating is the newest rating, having been created in April 2017 specifically for the drama series 13 Reasons Why.[8]

The Film and Video Labelling Body may award films, videos and DVDs an unrestricted classification of (G, PG or M) based on their Australian classification, or British classification if no Australian classification exists. The OLFC is the only body who may award restricted ratings.

Red labels have been available for non-film publications such as magazines and video games since 2005.[citation needed]

Classification law[]

The OFLC classifies material based on whether it is likely to be "harmful" or "injurious to the public good." Specifically (from the FVPC Act): "a publication is objectionable if it describes, depicts, expresses, or otherwise deals with matters such as sex, horror, crime, cruelty, or violence in such a manner that the availability of the publication is likely to be injurious to the public good." In 2000 the Court of Appeal of New Zealand decided in Living Word Distributors Limited v Human Rights Action Group (Wellington) [2000] NZCA 179 (a case involving two videos produced by Jeremiah Films) that the collocation of the words "sex, horror, crime, cruelty or violence" tends to point to activity rather than to the expression of opinion or attitude. On this interpretation, the OFLC had jurisdiction to restrict or ban publications describing or depicting sexual activities, but not those describing only an attitude or opinion about sex. The same interpretation required publications to describe or depict horror activities, criminal activities, cruel activities, and violent activities, rather than just an opinion or attitude about those things, for the OFLC to be able to classify them.

The Court of Appeal explicitly ruled that the phrase "matters such as sex" is strongly indicative of sexual activities and does not include sexual orientation. This made it more difficult for the OFLC to restrict or ban publications that simply exploited the nudity of children or portrayed classes of people as , but did not show any of the specified types of activity, notwithstanding the fact the FVPC Act directs the censors to give "particular weight" to these things when deciding whether or not to restrict or ban a publication. It also made it difficult for the OFLC to restrict publications simply containing offensive language or to ban videos of persons taken without their knowledge or consent, such as "upskirt" videos, on the ground of invasion of privacy, again because neither type of publication shows any of the specified types of activity. In 2005, Parliament amended the FVPC Act, and commenced amendment of the Crimes Act, to restore the OFLC's jurisdiction over all of these matters except for publications that simply portray classes of people as inherently inferior.

Under the FVPC Act material that promotes, supports, or tends to promote or support the following is deemed objectionable (banned):

- Sexual exploitation of children

- Coercion

- Extreme violence, torture, and/or cruelty

- Bestiality

- Necrophilia

- Urophilia

- Coprophilia

The Censorship Compliance Unit of the Department of Internal Affairs is responsible for the enforcement of the FVPC Act.

The Government has announced a regulatory change to bring commercial video on demand content from services like Netflix and Lightbox under the Films, Videos, and Publications Classification Act 1993. Providers would be able to self-classify within a New Zealand framework.

Currently streaming services are not covered by the same law that cinema movies or DVDs are and that means various providers use information from other countries or create their own.

Case studies[]

13 Reasons Why[]

Chief Censor Andrew Jack used his call-in power to classify the Netflix series 13 Reasons Why in 2017 and his successor David Shanks called in the second series in 2018.[citation needed]

The Chief Censors were concerned that New Zealand audiences needed to be warned about rape and suicide in the series. New Zealand has the highest youth suicide rate in the OECD.[9]

The series was given a specially created RP18 classification which means that someone under 18 must be supervised by a parent or guardian when viewing the series.[8] A guardian is considered to be a responsible adult (18 years and over), for example a family member or teacher who can provide guidance.[citation needed]

The use of the call-in power meant Netflix was required to clearly display the classification and warning.[citation needed]

A Star Is Born[]

A Star Is Born (2018) was not classified by the OFLC when it released in New Zealand. It had been rated an M in Australia so was automatically cross-rated M (Unrestricted, suitable for 16 years and over) in New Zealand by the Film & Video Labelling Body. At that stage, it carried a descriptive note ‘Sex scenes, offensive language and drug use.’ The Chief Censor required that the warning note be updated to include ‘suicide’ after receiving complaints from members of the public, including health care providers.[10]

The method of suicide used in A Star Is Born is the most common method of suicide in New Zealand.[11]

The Film & Video Labelling Body issued a new certificate to be displayed and alerted exhibitors to the note change so that they could update their information. Where possible, the distributor must update the label on all advertising.

The March 15 attack publications[]

Chief Censor David Shanks called in the livestream video of the Christchurch mosque shootings on 15 March 2019. The OFLC classified the full 17 minute footage as objectionable on 18 March 2019 due to its depiction and promotion of extreme violence and terrorism.[12]

A 74-page publication (referred to as The Great Replacement) reportedly written by the perpetrator of the Christchurch mosque shootings was also called in by Chief Censor David Shanks. It was officially classified as objectionable in New Zealand on 23 March 2019.[12]

The publication was found to provide justification for the Christchurch mosque shootings and to promote further acts of murder, terrorist violence, and extreme cruelty against identified groups of people. The objectionable classification was not due to the racist and extremist views expressed in the publication but due to the high likelihood of serious and fatal harm resulting from the continued availability of the publication.

Both decisions were reviewed by The Film and Literature Board of Review which also found the publications to be objectionable for the same reasoning as the OFLC.[13] The objectionable classification means it is illegal for the public in New Zealand to possess or distribute the publications without the express authority of the OFLC. The decisions of the OFLC and the Board of Review are only applicable to New Zealand and the publications continue to be legally available in other parts of the world.

Research[]

The Classification Office undertakes research about entertainment media content, media impacts, classification and censorship.[14] Recent projects have investigated young New Zealanders experiences and views about sexual violence in entertainment media, and online pornography.

| Published | Title |

|---|---|

| 2020 | Growing Up with Porn |

| 2019 | Breaking Down Porn: A Classification Office Analysis of Commonly Viewed Pornography in NZ |

| 2018 | |

| 2016–2017 | Young New Zealanders Viewing Sexual Violence |

| 2017 | Children and teen exposure to media content |

| 2016 | Understanding the Classification System: New Zealanders' Views |

| 2016 | Standardised classifications across different platforms |

| 2015 | Attitudes towards classification labels 2015 |

| 2014 | Comparing Classifications: feature films and video games 2012 & 2013 |

| 2013 | Young People's Research |

| 2013 | Comparing classifications 2010 & 2011 |

| 2013 | Attitudes towards classification labels |

| 2012 | What people think about film classification systems |

| 2011 | Guidance and Protection: What New Zealanders want from the classification system for films and games |

| 2011 | Understanding the Classification System: New Zealanders' views |

| 2010 | Young People's Use of Entertainment Mediums 2010 |

| 2010 | Parents and Gaming Literacy |

| 2009 | Report of a Public Consultation about The Last House on the Left |

| 2009 | A Review of Research on Sexual Violence in Audio-Visual Media |

| 2009 | Public Perceptions of a Violent Video Game X-Men Origins: Wolverine |

| 2008 | Viewing Violence: Audience Perceptions of Violent Content in Audio-Visual Entertainment |

| 2007 | Public Perceptions of Highly Offensive Language |

| 2007 | Public Understanding of Censorship |

| 2006 | Young People's Use of Entertainment Mediums |

| 2005 | The Viewing Habits of Users of Sexually Explicit Movies: a Hawke's Bay sample |

| 2005 | Underage Gaming Research |

| 2004 | The Viewing Habits of Users of Sexually Explicit Movies |

| 2003 | A Guide to the Research into the Effects of Sexually Explicit Films and Videos |

| 2002 | Public opinion research on sexually explicit videos |

| 2001 | Public consultation on sexually explicit videos |

| 2000 | Public and Professional Views Concerning the Classification and Rating of Films and Videos |

Community engagement[]

The OFLC also regularly convenes panels that are demographically representative of New Zealand as a whole to assist it with the classification of particular publications.[citation needed] It has convened public panels to assist it with the classification of films such as Baise-moi, Salo, Monster's Ball, Irréversible, Silent Hill, Du er ikke alene, Lolita, 8MM and Hannibal.

More frequently, the OFLC consults experts to assist it with the classification of various publications.[citation needed] For example, religious experts were consulted to assist with the classification of The Passion of the Christ, experts in road safety were consulted on , the Children's Commissioner on Ken Park and The Aristocrats, homeopathic practitioners on drug manufacturing books written by Steve Preisler[citation needed], various human rights organisations and the Vicar of Gisborne on a publication entitled Against Homosexuality[1], and rape crisis centres and psychologists on Irréversible and an edition of the University of Otago student magazine .

Each year the OFLC consults media studies students in its high school programme called Censor for a Day, during which an unreleased film is shown to high school students, who are then asked to classify it applying the criteria in the Films, Videos, and Publications Classification Act 1993.[citation needed] The students' classification is compared with, and usually identical to, the film's actual classification. Films used for Censor for a Day have included BlacKkKlansman, Get Out, Blockers, and Super Dark Times.

The Office works with a Youth Advisory panel of diverse young people aged 16–19 who provide a youth voice on media in New Zealand.[citation needed] Meetings are held once a month and are around two hours long. During the meetings, panel members express their views and perspectives on issues to do with potential media harms that impact on young people in New Zealand and the way the Classification Office responds to those issues. After a robust discussion, the panel members brainstorm what potential tangible outcomes could look like.

The panel regularly participate in classification assessments of upcoming feature films. Recently they helped with the classification of Boy Erased, Good Boys, and Booksmart. Their discussion is summarised in the classification decisions for those films.

List of Chief Censors[]

- William Jolliffe 1916–1927

- W. A. Tanner 1927–1937

- W. A. von Keisenberg 1938–1949

- Gordon Mirams 1949–1959

- Douglas McIntosh 1960–1976

- 1977–1983

- Arthur Everard 1984–1990

- Jane Wrightson 1991–1993

- Kathryn Paterson 1994–1998

- Bill Hastings 1999–2010

- Andrew Jack 2011–2017

- David Shanks 2017–present

The Chief Censor is the chief executive officer and chairperson of the Office of Film and Literature Classification.

See also[]

Further reading[]

- Angela Carr: Internet Traders of Child Pornography and Other Censorship Offenders in New Zealand: Department of Internal Affairs: Wellington: 2004 (available from the Department of Internal Affairs [2]

- David Wilson: Censorship In New Zealand: The Policy Challenges Of New Technology. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand 19 2002.[15]

- David Wilson: Responding to the challenges: recent developments in censorship policy in New Zealand. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand 30 2007.[16]

References[]

- ^ David Shanks (2019). Annual Report of the Office of Film & Literature Classification for the year ended 30 June 2019 (PDF) (Report). Office of Film and Literature Classification. p. 35. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ "Films, Videos, and Publications Classification Act". Section 2, Act of 1993.

- ^ Register of Classification Decisions (OFLC ref. 9501954) (Report). Office of Film and Literature Classification. 20 February 1996.

- ^ "Wicked Campers". Office of Film and Literature Classification. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ^ Notice of Decision under Section 38(1) (OFLC ref. 1600221.000) (PDF) (Report). Office of Film and Literature Classification. 28 April 2016.

- ^ Henry (2 February 2015). "Classifying clothing: how does the medium affect the classification? (Part 1)". Office of Film and Literature Classification. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ^ "Films, Videos, and Publications Classification Act". Section 80(1), Act of 1993.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stuff. "13 Reasons Why: Censors make new RP18 rating for controversial Netflix show". Stuff – via www.stuff.co.nz.

- ^ "The Social Report 2016 – Te pūrongo oranga tangata". Ministry of Social Development – via socialreport.msd.govt.nz/.

- ^ "A Star Is Born: Chief censor adds warning after young people 'severely triggered' by movie". Stuff. Stuff – via www.stuff.co.nz.

- ^ "Suicides by method, age, and district". Stuff. Stuff – via www.stuff.co.nz.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Office of Film and Literature Classification. "Christchurch attacks classification information". Office of Film and Literature Classification – via www.classificationoffice.govt.nz.

- ^ New Zealand Herald. "Review board dismisses appeal to lift ban on mosque shooting video". New Zealand Herald – via www.nzherald.co.nz.

- ^ "Research". Office of Film and Literature Classification. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ "Censorship In New Zealand: The Policy Challenges Of New Technology". Ministry of Social Development – via www.msd.govt.nz.

- ^ "Responding to the challenges: recent developments in censorship policy in New Zealand". Ministry of Social Development – via www.msd.govt.nz.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Office of Film and Literature Classification. |

- New Zealand independent crown entities

- Media content ratings systems

- New Zealand films

- Censorship in New Zealand

- Motion picture rating systems

- Entertainment rating organizations

- New Zealand literature