Pre-Islamic Arabia

Pre-Islamic Arabia | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Nabataean trade routes in Pre-Islamic Arabia | |||||||

| |||||||

Pre-Islamic Arabia[1] (Arabic: شبه الجزيرة العربية قبل الإسلام) is the Arabian Peninsula prior to the emergence of Islam in 610 CE.

Some of the settled communities developed into distinctive civilizations. Information about these communities is limited and has been pieced together from archaeological evidence, accounts written outside of Arabia, and Arab oral traditions which were later recorded by Islamic historians. Among the most prominent civilizations were the Thamud civilization, which arose around 3000 BCE and lasted to around 300 CE, and the earliest Semitic civilization in the eastern part was Dilmun,[2] which arose around the end of the fourth millennium and lasted to around 600 CE. Additionally, from the second half of the second millennium BCE,[3] Southern Arabia was the home to a number of kingdoms such as the Sabaeans, Minaeans, and Eastern Arabia was inhabited by Semitic speakers who presumably migrated from the southwest, such as the so-called Samad population. From 106 CE to 630 CE northwestern Arabia was under the control of the Roman Empire, which renamed it Arabia Petraea.[4] A few nodal points were controlled by Iranian Parthian and Sassanian colonists.

Pre-Islamic religions in Arabia included Arabian indigenous polytheistic beliefs, ancient Semitic religions (religions predating the Abrahamic religions which themselves likewise originated among the ancient Semitic-speaking peoples), various forms of Christianity, Judaism, Manichaeism, and Zoroastrianism.

Studies[]

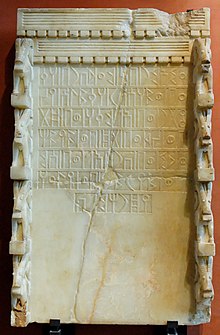

Scientific studies of Pre-Islamic Arabs starts with the Arabists of the early 19th century when they managed to decipher epigraphic Old South Arabian (10th century BCE), Ancient North Arabian (6th century BCE) and other writings of pre-Islamic Arabia. Thus, studies are no longer limited to the written traditions, which are not local due to the lack of surviving Arab historians' accounts of that era; the paucity of material is compensated for by written sources from other cultures (such as Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, etc.), so it was not known in great detail. From the 3rd century CE, Arabian history becomes more tangible with the rise of the Ḥimyarite, and with the appearance of the Qaḥṭānites in the Levant and the gradual assimilation of the Nabataeans by the Qaḥṭānites in the early centuries CE, a pattern of expansion exceeded in the Muslim conquests of the 7th century. Sources of history include archaeological evidence, foreign accounts and oral traditions later recorded by Islamic scholars—especially in the pre-Islamic poems—and the Ḥadīth, plus a number of ancient Arab documents that survived into medieval times when portions of them were cited or recorded. Archaeological exploration in the Arabian Peninsula has been sparse but fruitful; and many ancient sites have been identified by modern excavations. The most recent detailed study of pre-Islamic Arabia is Arabs and Empires Before Islam, published by Oxford University Press in 2015. This book collects a diverse range of ancient texts and inscriptions for the history especially of the northern region during this time period.

Prehistoric to Iron Age[]

- Ubaid period (5300 BCE) – could have originated in Eastern Arabia.

- Umm Al Nar culture (2600–2000 BCE)

- (2000 BCE)

- Wadi Suq Culture (1900–1300 BCE)

- = Early Iron Age (1300–300 BCE)

- Late Iron Age (c. 100 BCE–c.300 CE)

- (c. 150 BCE–c. 325 CE)

Magan, Midian, and ʿĀd[]

- Magan is attested as the name of a trading partner of the Sumerians. It is often assumed to have been located in Oman.

- The A'adids established themselves in South Arabia (modern-day Yemen), settling to the east of the Qahtan tribe. They established the Kingdom of ʿĀd around the 10th century BCE to the 3rd century CE.

The ʿĀd nation were known to the Greeks and Egyptians. Claudius Ptolemy's Geographos (2nd century CE) refers to the area as the "land of the Iobaritae" a region which legend later referred to as Ubar.[5]

The origin of the Midianites has not been established. Because of the Mycenaean motifs on what is referred to as Midianite pottery, some scholars including George Mendenhall,[6] Peter Parr,[7] and Beno Rothenberg[8] have suggested that the Midianites were originally Sea Peoples who migrated from the Aegean region and imposed themselves on a pre-existing Semitic stratum. The question of the origin of the Midianites still remains open.

Overview of major kingdoms[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2020) |

The history of Pre-Islamic Arabia before the rise of Islam in the 610s is not known in great detail. Archaeological exploration in the Arabian peninsula has been sparse; indigenous written sources are limited to the many inscriptions and coins from southern Arabia. Existing material consists primarily of written sources from other traditions (such as Egyptians, Greeks, Persians, Romans, etc.) and oral traditions later recorded by Islamic scholars. Many small kingdoms prospered from Red sea and Indian Ocean trade. Major kingdoms included the Sabaeans, Awsan, Himyar and the Nabateans

The first known inscriptions of the Kingdom of Hadhramaut are known from the 8th century BC[citation needed]. It was first referenced by an outside civilization in an Old Sabaic inscription of Karab'il Watar from the early 7th century BC[citation needed], in which the King of Hadramaut, Yada`'il, is mentioned as being one of his allies.

Dilmun appears first in Sumerian cuneiform clay tablets dated to the end of 4th millennium BC, found in the temple of goddess Inanna, in the city of Uruk. The adjective Dilmun refers to a type of axe and one specific official; in addition, there are lists of rations of wool issued to people connected with Dilmun.[9]

The Sabaeans were an ancient people speaking an Old South Arabian language who lived in what is today Yemen, in south west Arabian Peninsula; from 2000 BC to the 8th century BC. Some Sabaeans also lived in D'mt, located in Eritrea and northern Ethiopia, due to their hegemony over the Red Sea.[10] They lasted from the early 2nd millennium to the 1st century BC. In the 1st century BC it was conquered by the Himyarites, but after the disintegration of the first Himyarite empire of the Kings of Saba' and dhu-Raydan the Middle Sabaean Kingdom reappeared in the early 2nd century. It was finally conquered by the Himyarites in the late 3rd century.

The ancient Kingdom of Awsan with a capital at Hagar Yahirr in the wadi , to the south of the wadi Bayhan, is now marked by a tell or artificial mound, which is locally named . Once it was one of the most important small kingdoms of South Arabia. The city seems to have been destroyed in the 7th century BC by the king and mukarrib of Saba Karib'il Watar, according to a Sabaean text that reports the victory in terms that attest to its significance for the Sabaeans.

The Himyar was a state in ancient South Arabia dating from 110 BC. It conquered neighbouring Saba (Sheba) in c. 25 BC, Qataban in c. 200 AD and Hadramaut c. 300 AD. Its political fortunes relative to Saba changed frequently until it finally conquered the Sabaean Kingdom around 280 AD.[11] It was the dominant state in Arabia until 525 AD. The economy was based on agriculture.

Foreign trade was based on the export of frankincense and myrrh. For many years it was also the major intermediary linking East Africa and the Mediterranean world. This trade largely consisted of exporting ivory from Africa to be sold in the Roman Empire. Ships from Himyar regularly traveled the East African coast, and the state also exerted a considerable amount of political control of the trading cities of East Africa.

The Nabataean origins remain obscure. On the similarity of sounds, Jerome suggested a connection with the tribe Nebaioth mentioned in Genesis, but modern historians are cautious about an early Nabatean history. The Babylonian captivity that began in 586 BC opened a power vacuum in Judah, and as Edomites moved into Judaean grazing lands, Nabataean inscriptions began to be left in Edomite territory (earlier than 312 BC, when they were attacked at Petra without success by Antigonus I). The first definite appearance was in 312 BC, when Hieronymus of Cardia, a Seleucid officer, mentioned the Nabateans in a battle report. In 50 BC, the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus cited Hieronymus in his report, and added the following: "Just as the Seleucids had tried to subdue them, so the Romans made several attempts to get their hands on that lucrative trade."

Petra or Sela was the ancient capital of Edom; the Nabataeans must have occupied the old Edomite country, and succeeded to its commerce, after the Edomites took advantage of the Babylonian captivity to press forward into southern Judaea. This migration, the date of which cannot be determined, also made them masters of the shores of the Gulf of Aqaba and the important harbor of Elath. Here, according to Agatharchides, they were for a time very troublesome, as wreckers and pirates, to the reopened commerce between Egypt and the East, until they were chastised by the Ptolemaic rulers of Alexandria.

The Lakhmid Kingdom was founded by the Lakhum tribe that immigrated out of Yemen in the 2nd century and ruled by the Banu Lakhm, hence the name given it. It was formed of a group of Arab Christians who lived in Southern Iraq, and made al-Hirah their capital in (266). The founder of the dynasty was and the son Imru' al-Qais converted to Christianity. Gradually the whole city converted to that faith. Imru' al-Qais dreamt of a unified and independent Arab kingdom and, following that dream, he seized many cities in Arabia.

The Ghassanids were a group of South Arabian Christian tribes that emigrated in the early 3rd century from Yemen to the Hauran in southern Syria, Jordan and the Holy Land where they intermarried with Hellenized Roman settlers and Greek-speaking Early Christian communities. The Ghassanid emigration has been passed down in the rich oral tradition of southern Syria. It is said that the Ghassanids came from the city of Ma'rib in Yemen. There was a dam in this city, however one year there was so much rain that the dam was carried away by the ensuing flood. Thus the people there had to leave. The inhabitants emigrated seeking to live in less arid lands and became scattered far and wide. The proverb "They were scattered like the people of Saba" refers to that exodus in history. The emigrants were from the southern Arab tribe of Azd of the Kahlan branch of Qahtani tribes.

Eastern Arabia[]

The sedentary people of pre-Islamic Eastern Arabia were mainly Aramaic, Arabic and to some degree Persian speakers while Syriac functioned as a liturgical language.[12][13] In pre-Islamic times, the population of Eastern Arabia consisted of Christianized Arabs (including Abd al-Qays), Aramean Christians, Persian-speaking Zoroastrians[14] and Jewish agriculturalists.[12][15] According to Robert Bertram Serjeant, the Baharna may be the Arabized "descendants of converts from the original population of Christians (Aramaeans), Jews and ancient Persians (Majus) inhabiting the island and cultivated coastal provinces of Eastern Arabia at the time of the Arab conquest".[15][16] Other archaeological assemblages cannot be brought clearly into larger context, such as the Samad Late Iron Age.[17]

Zoroastrianism was also present in Eastern Arabia.[18][19][20] The Zoroastrians of Eastern Arabia were known as "Majoos" in pre-Islamic times.[21] The sedentary dialects of Eastern Arabia, including Bahrani Arabic, were influenced by Akkadian, Aramaic and Syriac languages.[22][23]

Dilmun[]

The Dilmun civilization was an important trading centre[24] which at the height of its power controlled the Persian Gulf trading routes.[24] The Sumerians regarded Dilmun as holy land.[25] Dilmun is regarded as one of the oldest ancient civilizations in the Middle East.[26][27] The Sumerians described Dilmun as a paradise garden in the Epic of Gilgamesh.[28] The Sumerian tale of the garden paradise of Dilmun may have been an inspiration for the Garden of Eden story.[28] Dilmun appears first in Sumerian cuneiform clay tablets dated to the end of fourth millennium BCE, found in the temple of goddess Inanna, in the city of Uruk. The adjective "Dilmun" is used to describe a type of axe and one specific official; in addition there are lists of rations of wool issued to people connected with Dilmun.[29]

Dilmun was an important trading center from the late fourth millennium to 1800 BCE.[24] Dilmun was very prosperous during the first 300 years of the second millennium.[30] Dilmun's commercial power began to decline between 2000 BCE and 1800 BCE because piracy flourished in the Persian Gulf. In 600 BCE, the Babylonians and later the Persians added Dilmun to their empires.

The Dilmun civilization was the centre of commercial activities linking traditional agriculture of the land with maritime trade between diverse regions as the Indus Valley and Mesopotamia in the early period and China and the Mediterranean in the later period (from the 3rd to the 16th century CE).[27]

Dilmun was mentioned in two letters dated to the reign of Burna-Buriash II (c. 1370 BCE) recovered from Nippur, during the Kassite dynasty of Babylon. These letters were from a provincial official, Ilī-ippašra, in Dilmun to his friend Enlil-kidinni in Mesopotamia. The names referred to are Akkadian. These letters and other documents, hint at an administrative relationship between Dilmun and Babylon at that time. Following the collapse of the Kassite dynasty, Mesopotamian documents make no mention of Dilmun with the exception of Assyrian inscriptions dated to 1250 BCE which proclaimed the Assyrian king to be king of Dilmun and Meluhha. Assyrian inscriptions recorded tribute from Dilmun. There are other Assyrian inscriptions during the first millennium BCE indicating Assyrian sovereignty over Dilmun.[31] Dilmun was also later on controlled by the Kassite dynasty in Mesopotamia.[32]

Dilmun, sometimes described as "the place where the sun rises" and "the Land of the Living", is the scene of some versions of the Sumerian creation myth, and the place where the deified Sumerian hero of the flood, Utnapishtim (Ziusudra), was taken by the gods to live forever. Thorkild Jacobsen's translation of the Eridu Genesis calls it "Mount Dilmun" which he locates as a "faraway, half-mythical place".[33]

Dilmun is also described in the epic story of Enki and Ninhursag as the site at which the Creation occurred. The promise of Enki to Ninhursag, the Earth Mother:

For Dilmun, the land of my lady's heart, I will create long waterways, rivers and canals, whereby water will flow to quench the thirst of all beings and bring abundance to all that lives.

Ninlil, the Sumerian goddess of air and south wind had her home in Dilmun. It is also featured in the Epic of Gilgamesh.

However, in the early epic "Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta", the main events, which center on Enmerkar's construction of the ziggurats in Uruk and Eridu, are described as taking place in a world "before Dilmun had yet been settled".

Gerrha[]

Gerrha (Arabic: جرهاء), was an ancient city of Eastern Arabia, on the west side of the Persian Gulf. More accurately, the ancient city of Gerrha has been determined to have existed near or under the present fort of Uqair.[citation needed] This fort is 50 miles northeast of al-Hasa in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. This site was first proposed by in 1924.

Gerrha and Uqair are archaeological sites on the eastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula.[34][35] Prior to Gerrha, the area belonged to the Dilmun civilization, which was conquered by the Assyrian Empire in 709 BCE. Gerrha was the center of an Arab kingdom from approximately 650 BCE to circa 300 CE. The kingdom was attacked by Antiochus III the Great in 205-204 BCE, though it seems to have survived. It is currently unknown exactly when Gerrha fell, but the area was under Sassanid Persian control after 300 CE.

Gerrha was described by Strabo[36] as inhabited by Chaldean exiles from Babylon, who built their houses of salt and repaired them by the application of salt water. Pliny the Elder (lust. Nat. vi. 32) says it was 5 miles in circumference with towers built of square blocks of salt.

Gerrha was destroyed by the Qarmatians in the end of the 9th century where all inhabitants were massacred (300,000).[37] It was 2 miles from the Persian Gulf near current day Hofuf. The researcher Abdulkhaliq Al Janbi argued in his book[38] that Gerrha was most likely the ancient city of Hajar, located in modern-day Al Ahsa, Saudi Arabia. Al Janbi's theory is the most widely accepted one by modern scholars, although there are some difficulties with this argument given that Al Ahsa is 60 km inland and thus less likely to be the starting point for a trader's route, making the location within the archipelago of islands comprising the modern Kingdom of Bahrain, particularly the main island of Bahrain itself, another possibility.[39]

Various other identifications of the site have been attempted, Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d'Anville choosing Qatif, Carsten Niebuhr preferring Kuwait and C Forster suggesting the ruins at the head of the bay behind the islands of Bahrain.

Tylos[]

Bahrain was referred to by the Greeks as Tylos, the centre of pearl trading, when Nearchus came to discover it serving under Alexander the Great.[40] From the 6th to 3rd century BCE Bahrain was included in Persian Empire by Achaemenians, an Iranian dynasty.[41] The Greek admiral Nearchus is believed to have been the first of Alexander's commanders to visit this islands, and he found a verdant land that was part of a wide trading network; he recorded: "That in the island of Tylos, situated in the Persian Gulf, are large plantations of cotton tree, from which are manufactured clothes called sindones, a very different degrees of value, some being costly, others less expensive. The use of these is not confined to India, but extends to Arabia."[42] The Greek historian, Theophrastus, states that much of the islands were covered in these cotton trees and that Tylos was famous for exporting walking canes engraved with emblems that were customarily carried in Babylon.[43] Ares was also worshipped by the ancient Baharna and the Greek colonists.[44]

It is not known whether Bahrain was part of the Seleucid Empire, although the archaeological site at Qalat Al Bahrain has been proposed as a Seleucid base in the Persian Gulf.[45] Alexander had planned to settle the eastern shores of the Persian Gulf with Greek colonists, and although it is not clear that this happened on the scale he envisaged, Tylos was very much part of the Hellenised world: the language of the upper classes was Greek (although Aramaic was in everyday use), while Zeus was worshipped in the form of the Arabian sun-god Shams.[46] Tylos even became the site of Greek athletic contests.[47]

The name Tylos is thought to be a Hellenisation of the Semitic, Tilmun (from Dilmun).[48] The term Tylos was commonly used for the islands until Ptolemy's Geographia when the inhabitants are referred to as 'Thilouanoi'.[49] Some place names in Bahrain go back to the Tylos era, for instance, the residential suburb of Arad in Muharraq, is believed to originate from "Arados", the ancient Greek name for Muharraq island.[50]

Herodotus's account (written c. 440 BCE) refers to the Io and Europa myths. (History, I:1).

Phoenicians Homeland[]

According to the Persians best informed in history, the Phoenicians began the quarrel. These people, who had formerly dwelt on the shores of the Erythraean Sea (the eastern part of the Arabia peninsula), having migrated to the Mediterranean and settled in the parts which they now inhabit, began at once, they say, to adventure on long voyages, freighting their vessels with the wares of Egypt and Assyria...

— Herodotus

The Greek historian Strabo believed the Phoenicians originated from Eastern Arabia.[51] Herodotus also believed that the homeland of the Phoenicians was Eastern Arabia.[52][53] This theory was accepted by the 19th-century German classicist Arnold Heeren who said that: "In the Greek geographers, for instance, we read of two islands, named Tyrus or Tylos, and Arad, Bahrain, which boasted that they were the mother country of the Phoenicians, and exhibited relics of Phoenician temples."[54] The people of Tyre in particular have long maintained Persian Gulf origins, and the similarity in the words "Tylos" and "Tyre" has been commented upon.[55] However, there is little evidence of occupation at all in Bahrain during the time when such migration had supposedly taken place.[56]

With the waning of Seleucid Greek power, Tylos was incorporated into Characene or Mesenian, the state founded in what today is Kuwait by Hyspaosines in 127 BCE. A building inscriptions found in Bahrain indicate that Hyspoasines occupied the islands, (and it also mention his wife, Thalassia).

Parthian and Sassanid[]

From the 3rd century BCE to arrival of Islam in the 7th century CE, Eastern Arabia was controlled by two other Iranian dynasties of the Parthians and Sassanids.

By about 250 BCE, the Seleucids lost their territories to Parthians, an Iranian tribe from Central Asia. The Parthian dynasty brought the Persian Gulf under their control and extended their influence as far as Oman. Because they needed to control the Persian Gulf trade route, the Parthians established garrisons in the southern coast of Persian Gulf.[57]

In the 3rd century CE, the Sassanids succeeded the Parthians and held the area until the rise of Islam four centuries later.[57] Ardashir, the first ruler of the Iranian Sassanians dynasty marched down the Persian Gulf to Oman and Bahrain and defeated Sanatruq [58] (or Satiran[41]), probably the Parthian governor of Eastern Arabia.[59] He appointed his son Shapur I as governor of Eastern Arabia. Shapur constructed a new city there and named it Batan Ardashir after his father.[41] At this time, Eastern Arabia incorporated the southern Sassanid province covering the Persian Gulf's southern shore plus the archipelago of Bahrain.[59] The southern province of the Sassanids was subdivided into three districts of Haggar (Hofuf, Saudi Arabia), Batan Ardashir (al-Qatif province, Saudi Arabia), and Mishmahig (Muharraq, Bahrain; also referred to as Samahij)[41] (In Middle-Persian/Pahlavi means "ewe-fish".[60]) which included the Bahrain archipelago that was earlier called Aval.[41][59] The name, meaning 'ewe-fish' would appear to suggest that the name /Tulos/ is related to Hebrew /ṭāleh/ 'lamb' (Strong's 2924).[61]

Beth Qatraye[]

The Christian name used for the region encompassing north-eastern Arabia was Beth Qatraye, or "the Isles".[62] The name translates to 'region of the Qataris' in Syriac.[63] It included Bahrain, Tarout Island, Al-Khatt, Al-Hasa, and Qatar.[64]

By the 5th century, Beth Qatraye was a major centre for Nestorian Christianity, which had come to dominate the southern shores of the Persian Gulf.[65][66] As a sect, the Nestorians were often persecuted as heretics by the Byzantine Empire, but eastern Arabia was outside the Empire's control offering some safety. Several notable Nestorian writers originated from Beth Qatraye, including Isaac of Nineveh, Dadisho Qatraya, Gabriel of Qatar and Ahob of Qatar.[65][67] Christianity's significance was diminished by the arrival of Islam in Eastern Arabia by 628.[68] In 676, the bishops of Beth Qatraye stopped attending synods; although the practice of Christianity persisted in the region until the late 9th century.[65]

The dioceses of Beth Qatraye did not form an ecclesiastical province, except for a short period during the mid-to-late seventh century.[65] They were instead subject to the Metropolitan of Fars.

Beth Mazunaye[]

Oman and the United Arab Emirates comprised the ecclesiastical province known as Beth Mazunaye. The name was derived from 'Mazun', the Persian name for Oman and the United Arab Emirates.[62]

South Arabian kingdoms[]

Kingdom of Ma'īn (10th century BCE – 150 BCE)[]

During Minaean rule, the capital was at Karna (now known as Sa'dah). Their other important city was Yathill (now known as Baraqish). The Minaean Kingdom was centered in northwestern Yemen, with most of its cities lying along Wādī . Minaean inscriptions have been found far afield of the Kingdom of Maīin, as far away as al-'Ula in northwestern Saudi Arabia and even on the island of Delos and Egypt. It was the first of the Yemeni kingdoms to end, and the Minaean language died around 100 CE .[69] [70] [71]

Kingdom of Saba (12th century BCE – 7th century CE)[]

During Sabaean rule, trade and agriculture flourished, generating much wealth and prosperity. The Sabaean kingdom was located in Yemen, and its capital, Ma'rib, is located near what is now Yemen's modern capital, Sana'a.[72] According to South Arabian tradition, the eldest son of Noah, Shem, founded the city of Ma'rib. [73]

During Sabaean rule, Yemen was called "Arabia Felix" by the Romans, who were impressed by its wealth and prosperity. The Roman emperor Augustus sent a military expedition to conquer the "Arabia Felix", under the command of Aelius Gallus. After an unsuccessful siege of Ma'rib, the Roman general retreated to Egypt, while his fleet destroyed the port of Aden in order to guarantee the Roman merchant route to India.

The success of the kingdom was based on the cultivation and trade of spices and aromatics including frankincense and myrrh. These were exported to the Mediterranean, India, and Abyssinia, where they were greatly prized by many cultures, using camels on routes through Arabia, and to India by sea.

During the 8th and 7th century BCE, there was a close contact of cultures between the Kingdom of Dʿmt in Eritrea and northern Ethiopia and Saba. Though the civilization was indigenous and the royal inscriptions were written in a sort of proto-Ethiosemitic, there were also some Sabaean immigrants in the kingdom as evidenced by a few of the Dʿmt inscriptions.[74][75]

Agriculture in Yemen thrived during this time due to an advanced irrigation system which consisted of large water tunnels in mountains, and dams. The most impressive of these earthworks, known as the Marib Dam, was built ca. 700 BCE and provided irrigation for about 25,000 acres (101 km2) of land[76] and stood for over a millennium, finally collapsing in 570 CE after centuries of neglect.

Kingdom of Hadhramaut (8th century BCE – 3rd century CE)[]

The first known inscriptions of Hadramaut are known from the 8th century BCE. It was first referenced by an outside civilization in an Old Sabaic inscription of Karab'il Watar from the early 7th century BCE, in which the King of Hadramaut, Yada`'il, is mentioned as being one of his allies. When the Minaeans took control of the caravan routes in the 4th century BCE, however, Hadramaut became one of its confederates, probably because of commercial interests. It later became independent and was invaded by the growing Yemeni kingdom of Himyar toward the end of the 1st century BCE, but it was able to repel the attack. Hadramaut annexed Qataban in the second half of the 2nd century CE, reaching its greatest size. The kingdom of Hadramaut was eventually conquered by the Himyarite king Shammar Yahri'sh around 300 CE, unifying all of the South Arabian kingdoms.[77]

Kingdom of Awsān (8th century BCE – 6th century BCE)[]

The ancient Kingdom of Awsān in South Arabia (modern Yemen), with a capital at Ḥagar Yaḥirr in the wadi Markhah, to the south of the Wādī Bayḥān, is now marked by a tell or artificial mound, which is locally named .

Kingdom of Qataban (4th century BCE – 3rd century CE)[]

Qataban was one of the ancient Yemeni kingdoms which thrived in the Beihan valley. Like the other Southern Arabian kingdoms, it gained great wealth from the trade of frankincense and myrrh incense, which were burned at altars. The capital of Qataban was named Timna and was located on the trade route which passed through the other kingdoms of Hadramaut, Saba and Ma'in. The chief deity of the Qatabanians was Amm, or "Uncle" and the people called themselves the "children of Amm".

Kingdom of Himyar (late 2nd century BCE – 525 CE)[]

The Himyarites rebelled against Qataban and eventually united Southwestern Arabia (Hejaz and Yemen), controlling the Red Sea as well as the coasts of the Gulf of Aden. From their capital city, Ẓafār, the Himyarite kings launched successful military campaigns, and had stretched its domain at times as far east as eastern Yemen and as far north as Najran[78] Together with their Kindite allies, it extended maximally as far north as Riyadh and as far east as .

During the 3rd century CE, the South Arabian kingdoms were in continuous conflict with one another. Gadarat (GDRT) of Aksum began to interfere in South Arabian affairs, signing an alliance with Saba, and a Himyarite text notes that Hadramaut and Qataban were also allied against the kingdom. As a result of this, the Aksumite Empire was able to capture the Himyarite capital of Thifar in the first quarter of the 3rd century. However, the alliances did not last, and Sha`ir Awtar of Saba unexpectedly turned on Hadramaut, allying again with Aksum and taking its capital in 225. Himyar then allied with Saba and invaded the newly taken Aksumite territories, retaking Thifar, which had been under the control of Gadarat's son Beygat, and pushing Aksum back into the Tihama.[79][80] The standing relief image of a crowned man, is taken to be a representation possibly of the Jewish king Malkīkarib Yuhaʾmin or more likely the Christian Esimiphaios (Samu Yafa').[81]

Aksumite occupation of Yemen (525 – 570 CE)[]

The Aksumite intervention is connected with Dhu Nuwas, a Himyarite king who changed the state religion to Judaism and began to persecute the Christians in Yemen. Outraged, Kaleb, the Christian King of Aksum with the encouragement of the Byzantine Emperor Justin I invaded and annexed Yemen. The Aksumites controlled Himyar and attempted to invade Mecca in the year 570 CE. Eastern Yemen remained allied to the Sassanids via tribal alliances with the Lakhmids, which later brought the Sassanid army into Yemen, ending the Aksumite period.

Sassanid period (570 – 630 CE)[]

The Persian king Khosrau I sent troops under the command of Vahriz (Persian: اسپهبد وهرز), who helped the semi-legendary Sayf ibn Dhi Yazan to drive the Aksumites out of Yemen. Southern Arabia became a Persian dominion under a Yemenite vassal and thus came within the sphere of influence of the Sassanid Empire. After the demise of the Lakhmids, another army was sent to Yemen, making it a province of the Sassanid Empire under a Persian satrap. Following the death of Khosrau II in 628, the Persian governor in Southern Arabia, Badhan, converted to Islam and Yemen followed the new religion.

Hejaz[]

Kingdom of Lihyan/Dedan (7th century BCE - 24 BC)[]

Lihyan, also called Dadān or Dedan, was a powerful and highly organized ancient Arab kingdom that played a vital cultural and economic role in the north-western region of the Arabian Peninsula and used Dadanitic language. [82] The Lihyanite kingdom went through three different stages, the early phase of Lihyan Kingdom was around the 7th century BC, started as a Sheikdom of Dedan then developed into the Kingdom of Lihyan tribe.[83] Some authors assert that the Lihyanites fell into the hands of the Nabataeans around 65 BC upon their seizure of Hegra then marching to Tayma, and finally to their capital Dedan in 9 BC. Werner Cascel consider the Nabataean annexation of Lihyan was around 24 BC under the reign of the Nabataeans king Aretas IV.

Thamud[]

The Thamud (Arabic: ثمود) was an ancient civilization in Hejaz, which flourished kingdom from 3000 BCE to 200 BCE. Recent archaeological work has revealed numerous Thamudic rock writings and pictures. They are mentioned in sources such as the Qur'an,[84][85][86][87][88][89] old Arabian poetry, Assyrian annals (Tamudi), in a Greek temple inscription from the northwest Hejaz of 169 CE, in a 5th-century Byzantine source and in Old North Arabian graffiti within Tayma. They are also mentioned in the victory annals of the Neo-Assyrian King, Sargon II (8th century BCE), who defeated these people in a campaign in northern Arabia. The Greeks also refer to these people as "Tamudaei", i.e. "Thamud", in the writings of Aristotle, Ptolemy, and Pliny. Before the rise of Islam, approximately between 400 and 600 CE, the Thamud completely disappeared.

North Arabian kingdoms[]