Quincy, Florida

hideThis article has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Quincy, Florida | |

|---|---|

Quincy City Hall | |

| Motto(s): "...In the heart of Florida's future"[1] | |

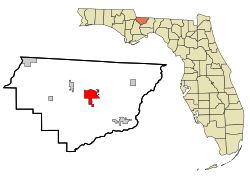

Location in Gadsden County and the state of Florida | |

Quincy, Florida Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 30°35′N 84°35′W / 30.583°N 84.583°WCoordinates: 30°35′N 84°35′W / 30.583°N 84.583°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Florida |

| County | Gadsden |

| Government | |

| • Type | Manager- Commission |

| • Mayor | Ronte R. Harris |

| • Mayor Pro Tem | Angela Grant Sapp |

| • Commissioners | Keith A. Dowdell, Freida Bass-Prieto, Anessa Canidate |

| • City Manager | Jack McLean, Jr. |

| • City Clerk | Vacant |

| Area | |

| • Total | 11.54 sq mi (29.88 km2) |

| • Land | 11.54 sq mi (29.88 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 207 ft (63 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 7,972 |

| • Estimate (2019)[5] | 6,827 |

| • Density | 591.80/sq mi (228.50/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 32351-32353 |

| Area code(s) | 850 |

| FIPS code | 12-59325[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0289404[4] |

| Website | www |

Quincy is a city in Gadsden County, Florida, United States. The population was 7,972 at the 2010 census,[6] up from 6,982 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat of Gadsden County.[7][8] Quincy is part of the Tallahassee, Florida Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History[]

Established in 1828, Quincy is the county seat of Gadsden County, and was named for John Quincy Adams.[8] It is located 25 miles (40 km) northwest of Tallahassee, the state capital. Quincy's economy was based on agriculture, including farming tomatoes, tobacco, mushrooms, soybeans and other crops.

According to The Floridian newspaper, in 1840 before there were public schools anywhere else in the Florida Territory, there were in Quincy the Quincy Male Academy[9] and the Quincy Female Academy.[10] published the Quincy Sentinel in Quincy from November 1839 until it relocated to Tallahassee and became the Florida Sentinel in 1841.[11] The paper began publishing in Tallahassee in February or March 1841 as a successor to Quincy Sentinel.[12]

Tobacco[]

In 1828, Governor William P. Duval introduced Cuban tobacco to the territory of Florida. As a result, the culture of shade-grown cigar wrapper tobacco was a dominant factor in the social and economic development of Gadsden County. Tobacco is a native plant of the western hemisphere. Early European explorers discovered Native Americans growing the plant when they set foot on their soil.

In 1829, John Smith migrated to Gadsden County in covered wagons with his family and four related families. Since there was already a resident named John Smith in the community, he became known as John "Virginia" Smith. When Smith ventured southward he brought with him a type of tobacco seed which was used for chewing and pipe smoking. He planted that seed and found that the plants grew vigorously. Because there was no market for tobacco in small quantities, it was twisted together, cured and shared with his friends. He purchased some Cuban tobacco seed and planted them with his Virginia tobacco. Several years passed and the two tobaccos blended.

When the Virginia tobacco was grown in Florida soil, it was much thinner and lighter in color. Smith began saving the seed from the hybridized stalks. From these seeds, a new plant known as "Florida Wrapper" was developed. So began a tobacco industry at a time when the South was suffering from the low price of cotton.

Growing tobacco continued to be profitable until the beginning of the Civil War in 1861, even when the European markets were no longer available. Of course, during the war and the Reconstruction Era, very little tobacco was grown except for personal use. Those days were tremendously difficult, and recovery was a slow process. The post-war search for a money crop led to the resurgence of the tobacco culture. Through these experiments it was discovered that tobacco which was light in color and silky in texture demanded the highest prices. With more experimentation, shading the plants began. At first, wood slats were used, but these proved too heavy. Then they tried slats draped with cheesecloth to keep the plants from the light. Next came ribbed cheesecloth. Ultimately in 1950, the white cheesecloth was replaced with a treated, longer lasting, yellow cloth that provided perfect shade.

Colonel Henry DuVal, president of the Florida Central and Peninsular Railroad, shipped samples of Gadsden County tobacco to New York for leaf dealers and cigar manufacturers to inspect. Soon representatives of several companies came down from New York to purchase land for growing tobacco. There was such an influx of land purchases that a number of packing houses arose. This continued until 1970 when tobacco companies came under fire and demand diminished. Around 1970, growing tobacco declined substantially in Gadsden. The development of a homogenized cigar wrapper, the ever-increasing cost of production, the subsidizing of the tobacco culture in Central America by the U.S. government, and the increasing, negative legal climate against the tobacco industry have added to the demise of Gadsden's future in tobacco. The last crop of shade-grown cigar wrapper tobacco was grown in 1977.

Quincy then turned to its other crops, tomato, mushroom and egg farms. This continued until the close of Quincy's mushroom factory and massive layoff of workers at Quincy's tomato farm in 2008. Quincy now turns to its businesses and is attempting to build itself into a business-based district.[13]

Race relations[]

Lynchings[]

In 1929, Will Larkins was accused of an attack on a white 13 year old Quincy school girl, for which he was quickly indicted. [14] As Larkins was being transferred he was taken by a mob of 40 masked men from Sheriff Gregory of Gadsden county, [15] near Madison and Live Oak. When he was kidnapped by the mob he was being taken to the Duval county jail in a series of moves that newspapers claimed were for his safe keeping.[16] After his capture by the mob Larkins was carried back to Quincy, near the railroad grade crossing, shot to death and hanged with wire,[17] his body was then dragged through the street tied to an automobile and burned at the area where the mob thought the accused committed his crime.[18] Though Governor Carlton promised an inquiry and investigators were put on the case in late 1929, no mention of Will Larkins, except for the NAACP lynching lists of 1929, is made again in newspapers of the time. Larkins was the third man lynched in Florida that year. [19]

In 1941, A. C. Williams was accused of robbery and the attempted rape of a 12 year old white girl. The account of the details makes the accusation very improbable, but Williams did not live long enough to be tried for the crime. He was kidnapped from jail by a group of white men, and although they both shot him and hanged him, Williams survived. After learning he was alive, the sheriff formed a search party. His family was aware the sheriff had been involved in the lynching, and hid him. Unfortunately, Williams needed medical attention and since the hospitals in the Quincy area would not treat a black person, he needed to be transported to Florida A&M University in Tallahassee. The following day a group of masked men kidnapped him from the ambulance and killed him. His body was dumped on his mother's porch.[20][21]

Resistance to Jim Crow[]

In the 1920s, blacks in Quincy including A. I. Dixie repeatedly tried to form political organizations and vote, and protest brutal labor conditions, but were suppressed by violence from whites. Dixie was flogged repeatedly for his efforts. Later, in 1964, Dixie hosted Congress of Racial Equality student activists, while his daughter Linda organized a sit-in, and Jewell Dixie became the first African American to run for Gadsden County Sheriff.[22][23]

All American City[]

In 1996, Quincy was recognized as an All American City.[24]

Essence article[]

In February 2003, an article in Essence magazine incorrectly stated that Quincy was the city with the most AIDS cases in Florida.[25] Some residents of the city were upset with the negative publicity.[25][26] "Quincy has no more AIDS cases than typical rural cities in Florida", the mayor, Keith Dowdell, stated, and the city with the highest number of AIDS cases in Florida in 2003 was Palm Beach, not Quincy.[citation needed] The article claimed that African-American females represented 90% of AIDS cases in Quincy,[27] although the highest percentage of AIDS cases in Quincy at that time was in males.[28]

Geography[]

Quincy is located in central Gadsden County at 30°35′N 84°35′W / 30.583°N 84.583°W (30.59, -84.58),[29] in the rolling hills of North Florida.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 7.9 square miles (20.5 km2), of which 0.02 square miles (0.04 km2), or 0.18%, is water.[6]

Climate[]

| hideClimate data for Quincy 3 SSW, Florida, 1991-2020 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (��C) | 63.9 (17.7) |

66.8 (19.3) |

72.6 (22.6) |

78.9 (26.1) |

86.2 (30.1) |

89.9 (32.2) |

91.3 (32.9) |

90.8 (32.7) |

87.9 (31.1) |

81.1 (27.3) |

73.0 (22.8) |

66.5 (19.2) |

79.1 (26.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 51.9 (11.1) |

54.0 (12.2) |

59.5 (15.3) |

66.1 (18.9) |

74.2 (23.4) |

79.4 (26.3) |

81.5 (27.5) |

81.2 (27.3) |

77.7 (25.4) |

69.4 (20.8) |

60.0 (15.6) |

54.0 (12.2) |

67.4 (19.7) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 39.8 (4.3) |

41.1 (5.1) |

46.4 (8.0) |

53.2 (11.8) |

62.2 (16.8) |

68.9 (20.5) |

71.6 (22.0) |

71.5 (21.9) |

67.4 (19.7) |

57.7 (14.3) |

46.9 (8.3) |

41.5 (5.3) |

55.7 (13.2) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.81 (122) |

4.62 (117) |

5.20 (132) |

3.89 (99) |

4.46 (113) |

6.30 (160) |

7.01 (178) |

6.05 (154) |

6.09 (155) |

3.93 (100) |

3.60 (91) |

3.85 (98) |

59.81 (1,519) |

| Source: NOAA[30][31] | |||||||||||||

Demographics[]

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 743 | — | |

| 1880 | 639 | −14.0% | |

| 1890 | 681 | 6.6% | |

| 1900 | 847 | 24.4% | |

| 1910 | 3,204 | 278.3% | |

| 1920 | 3,118 | −2.7% | |

| 1930 | 3,788 | 21.5% | |

| 1940 | 3,888 | 2.6% | |

| 1950 | 6,505 | 67.3% | |

| 1960 | 8,874 | 36.4% | |

| 1970 | 8,334 | −6.1% | |

| 1980 | 8,591 | 3.1% | |

| 1990 | 7,444 | −13.4% | |

| 2000 | 6,982 | −6.2% | |

| 2010 | 7,972 | 14.2% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 6,827 | [5] | −14.4% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[32] | |||

As of the census[3] of 2000, there were 6,982 people, 2,657 households, and 1,830 families residing in the city. The population density was 916.4 inhabitants per square mile (353.8/km2). There were 2,917 housing units at an average density of 382.9 per square mile (147.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 31.55% White, 64.15% African American, 0.16% Native American, 0.23% Asian, 3.22% from other races, and 0.69% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 6.89% of the population.

There were 2,657 households, out of which 30.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 36.2% were married couples living together, 28.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 31.1% were non-families. 27.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.60 and the average family size was 3.17.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 27.8% under the age of 18, 9.6% from 18 to 24, 25.7% from 25 to 44, 20.6% from 45 to 64, and 16.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females, there were 80.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 72.1 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $29,393, and the median income for a family was $31,890. Males had a median income of $27,871 versus $22,025 for females. The per capita income for the city was $15,133. About 16.8% of families and 19.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 24.0% of those under age 18 and 23.1% of those age 65 or over.

Arts and culture[]

Museums and other points of interest[]

Several locations in Quincy have been included in the National Register of Historic Places, most within the boundary of the Quincy Historic District. They are:

- E. B. Shelfer House

- E. C. Love House

- John Lee McFarlin House

- Judge P. W. White House

- Old Philadelphia Presbyterian Church

- Quincy Library

- Quincy Woman's Club

- Stockton-Curry House

- Willoughby Gregory House

The Gadsden Arts Center,[33] an AAM accredited art museum[34] housed in the renovated 1912 Bell & Bates hardware store, with rotating regional & national art exhibitions and a permanent collection of Vernacular Art, is also situated in the Quincy Historic District.

Also notable is the Leaf Theater, which is considered a "historic cinema treasure".[35] It is also said to be haunted.[36]

Also notable on the outskirts of the city are the Florida A&M research and development center located on Old Bainbridge Road in the St. John community.[37][38]

The Golf Club of Quincy is on Highway 268 in the Farms Community.[39]

The North Florida Research and Education center is on Pat Thomas Parkway in Quincy.[40]

Media[]

Quincy has two local papers that cover all of Gadsden County, of Gadsden County and The Herald of the city of Havana, Florida.

Education[]

The Gadsden County School District operates area public schools.

- Carter-Parramore Academy School

- Chattahoochee Elementary School

- Crossroad Academy Charter School

- Gadsden Central Academy School

- Gadsden County High School

- Gadsden Elementary Magnet School

- Gadsden Technical Institute School

- George W. Munroe Elementary School

- Greensboro Elementary School

- Havana Magnet School

- James A. Shanks Middle School

- Stewart Street Elementary School

- West Gadsden Middle School[41]

In 2003 James A. Shanks High School in Quincy and Havana Northside High School consolidated into East Gadsden High School.[42] In 2017 East Gadsden High became the only zoned high school in the county due to the consolidation of the high school section of West Gadsden High School into East Gadsden.[43]

Robert F. Munroe Day School, a K-12 private school, has its kindergarten campus, the Robert F. Munroe Day Kindergarten, in Quincy proper.[44] The main campus for grade 1–12 in nearby Mount Pleasant.[45]

The Gadsden County Public Library system operates the William A. "Bill" McGill Public Library.

Gadsden Magnet Elementary School (former Quincy High School)

George W. Munroe Elementary School

Stewart Street Elementary School

Robert F. Munroe Kindergarten (private)

William A. "Bill" McGill Public Library

Transportation[]

Highways[]

U.S. Route 90 (Jefferson Street) is the main highway through the city; US 90 leads southeast 24 miles (39 km) to Tallahassee and northwest 19 miles (31 km) to Chattahoochee. The city limits extend south to beyond Interstate 10, which passes 3 miles (5 km) south of the center of the city. I-10 leads east 22 miles (35 km) to Tallahassee and west 170 miles (270 km) to Pensacola.

Other highways in Quincy include SR 12, which leads 12 miles (19 km) to Havana and southwest 28 miles (45 km) to Bristol; SR 267, which leads north 8 miles (13 km) to the Georgia line and south 8 miles to Wetumpka; and , which leads southeast 11 miles (18 km) to Midway.

Transit[]

Shuttle-bus and van transportation between Quincy and Chattahoochee, Havana, and Tallahassee is provided by , which operates three routes serving the area.[46]

Railroad[]

Freight service is provided by the Florida Gulf & Atlantic Railroad, which acquired most of the former CSX main line from Pensacola to Jacksonville on June 1, 2019.

Airport[]

Quincy Municipal Airport is a public-use airport located 2 miles (3.2 km) northeast of the central business district.

Coca-Cola[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2013) |

Quincy investors were largely responsible for the development of its local Coca-Cola company into a worldwide conglomerate. Quincy was once rumored to be home to many millionaires due to the Coca-Cola boom. Pat Munroe, a banker, father of 18 children by two wives, and W.C. Bradley were among the stockholders of three of the banks that released 500,000 shares of new Coca-Cola common stock. They urged widows and farmers to invest for $40 each, and several did.[47][48][49][50][51][52] Eventually that stock split, and made as many as 67 accounted-for investors and Gadsden County residents rich. In perspective, a single share of Coca-Cola stock bought in 1919 for $40 would be worth $6.4 million today, if all dividends had been reinvested.[8]

Notable people[]

- Nat Adderley Jr. (b. 1955), music arranger who spent much of his career with Luther Vandross[53]

- The Lady Chablis (1957–2016), born Benjamin Edward Knox,[54] transgender entertainer best known for her appearance in the book and subsequent movie adaptation of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil

- Elizabeth Whitfield Croom Bellamy (1837–1900), writer

- Billy Dean (b. 1962), country music singer

- Freddie Figgers (b. 1989), electronics inventor and entrepreneur

- Mack Lee Hill (1940–1965), football player and American Football League All-Pro RB for the Kansas City Chiefs

- Willy Holt (1921–2007), French-American film production designer and art director

- Dexter Jackson (b. 1977), football player and Super Bowl XXXVII MVP

- Jerrie Mock (1925–2014), first woman to fly solo around the world

- Quincy Five, five men wrongfully convicted of murder

- Willie Simmons (b. 1980), head coach of the Florida A&M Rattlers football team

Gallery[]

Downtown Quincy on US90

Police department

Quincy Fire Department

Joseph L. Ferolito Recreation Center

Quincy Post Office

References[]

- ^ "The City of Quincy Florida Website". The City of Quincy Florida Website. Retrieved September 21, 2012.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Quincy city, Florida". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved November 21, 2016.[dead link]

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Profile for Quincy, Florida, FL". ePodunk. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ "Quincy Male Academy". The Floridian (Tallahassee, Florida). January 18, 1840. p. 1.

- ^ Edwards, R. I., principal (January 18, 1840). "Quincy Female Academy". The Floridian (Tallahassee, Florida). p. 1.

- ^ "Florida Historical Quarterly". Florida Historical Society. March 2, 1942 – via Google Books.

- ^ Knauss, James Owen (March 2, 1926). "Territorial Florida journalism". The Florida state historical society – via Google Books.

- ^ State Library and Archives of Florida. "Florida Memory - Workers harvesting wrapper tobacco - Quincy, Florida". Florida Memory.

- ^ "QUINCY NEGRO IN JAIL HERE" Tallahassee Democrat, 08 Nov 1929, Fri • Page 1; "GIRL ATTACKED ON WAY TO HOME" The Miami Herald,09 Nov 1929, Sat, Page 3

- ^ "LARKINS WAS TAKEN FROM SHERIFF ON WAY TO JAX" Pensacola News Journal, 10 Nov 1929, Sun • Page 1

- ^ "QUINCY NEGRO IN JAIL HERE" Tallahassee Democrat, 08 Nov 1929, Fri • Page 1

- ^ "NEGRO LYNCHED IN FLORIDA BY MOB"Albuquerque Journal, 10 Nov 1929, Sun • Page 1.

- ^ "Lynch Negro Charged With Attack on 12 Year Old Girl" The Tribune, Scranton, Pennsylvania, 11 Nov 1929, Mon, Page 1

- ^ "Carlton Promies Inquiry" The Tampa Tribune, 12 Nov 1929, Tue, Page 1

- ^ Hobbs, Tameka Bradley. ""Hitler Is Here": Lynching in Florida during the Era of World War II". Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ^ Hobbs, Tameka (2016). Democracy Abroad, Lynching at Home: Racial Violence in Florida. ISBN 9780813062396.

- ^ Ortiz, Paul (30 November 2001). "African-American Resistance to Jim Crow in the South".

- ^ Granade, Ray (July 1976). "Slave Unrest in Florida" (PDF). Florida Historical Quarterly: 18–36.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 4, 2013. Retrieved November 1, 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b "AIDS: A Community Fights Back". WCTV. February 19, 2004. Retrieved November 19, 2016.

- ^ [1][permanent dead link]

- ^ "Residents of Small Florida Town 'In An Uproar' Over Essence Article Detailing Its Efforts to Address HIV/AIDS". January 24, 2003.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 22, 2013. Retrieved June 23, 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ^ "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991-2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Gadsden Arts Center & Museum > Home". www.gadsdenarts.org.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-03-14. Retrieved 2016-03-09.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Quincy Music Theatre. Cinema Treasures. Accessed 2013-03-04.

- ^ "Quincy Leaf Theater/The Quincy Music Theater".

- ^ https://www.famu.edu/cesta/main/index.cfm/cooperative-extension-program/famu-farm/

- ^ https://www.tallahassee.com/story/life/causes/2015/06/08/famu-invites-visitors-tour-quincy-farm/28673921/>

- ^ http://golfclubofquincy.com/

- ^ https://nfrec.ifas.ufl.edu/

- ^ http://www.gcps.k12.fl.us/?PN=Schools2. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ Miller, Brian (2017-01-30). "Striplin goes from West Gadsden to East, schools likely to consolidate". Tallahassee Democrat. Retrieved 2017-04-05.

- ^ Jiwanmall, Stephen (2017-04-04). "Gadsden County Schools to Consolidate in 2017-18". WTXL. Retrieved 2017-04-06.

- ^ "Robert F. Munroe Day School 91 Old Mt. Pleasant Road Quincy, Florida 32352" and "Robert F. Munroe Day Kindergarten 1800 West King Street Quincy, Florida 32351"

- ^ "About Us." Robert F. Munroe Day School. Retrieved on June 5, 2017. "Founded in 1969 in Mt. Pleasant, Florida, the campus[...]" and "91 Old Mt. Pleasant Rd. Quincy FL, 32352"

- ^ "Big Bend Transit | COORDINATED TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM OF GADSDEN COUNTY". www.bigbendtransit.org. Retrieved 2019-01-31.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 18, 2014. Retrieved June 22, 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Gary McKechnie. "The Coca-Cola Millionaires of Quincy, Florida". visitflorida.com.

- ^ "Quincy Florida: America's Coke Habit Made the Town Rich".

- ^ "Quincy's Drink of Choice". tallahasseemagazine.com. Archived from the original on 2015-06-10. Retrieved 2013-06-22.

- ^ "Quincy Florida: America's Coke Habit Made The Town Rich". Florida Backroads Travel.

- ^ "Coke millions fortify a town Shareholders: The Coca-Cola stock that some Quincy, Fla., tobacco farmers bought 74 years ago is still held today by the town's "Coke millionaires," whose generosity has made Quincy a better place to live". Baltimore Sun.

- ^ Stewart, Zan. "Born to swing: Nat Adderley Jr. returns to his roots", The Star-Ledger, September 10, 2009. Accessed September 10, 2009.

- ^ The Lady Chablis Sassy Transgender Figure in Savannah Book, Movie Dies at-59." Washington Post, Sept. 9, 2016. Retrieved on Sept. 12, 2016.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Quincy, Florida. |

- City of Quincy official website

- Virtual Tour of Quincy

- City-Data.com, comprehensive statistical data about Quincy

- Cities in Gadsden County, Florida

- County seats in Florida

- Tallahassee metropolitan area

- Cities in Florida

- 1828 establishments in Florida Territory

- Populated places established in 1828