Regency era

| c. 1811 – 1820 | |

| |

| Preceded by | Georgian era |

|---|---|

| Followed by | Victorian era |

| Monarch(s) |

|

| Leader(s) | George, Prince Regent[1] |

| Periods in English history |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

The Regency era in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was a period towards the end of the Georgian era, when King George III was deemed unfit to rule due to his illness and his son ruled as his proxy, as prince regent. Upon George III's death in 1820, the prince regent became King George IV. The terms Regency or Regency era can refer to various periods of time; some are longer than the decade of the formal Regency from 1811 to 1820. The period from 1795 to 1837, which includes the latter part of George III's reign and the reigns of his sons George IV and William IV, is sometimes regarded as the Regency era,[2] characterised by distinctive trends in British architecture, literature, fashions, politics, and culture.

Society[]

The Regency is noted for its elegance and achievements in the fine arts and architecture. This era encompassed a time of great social, political, and economic change. War was waged with Napoleon and on other fronts, affecting commerce both at home and internationally, as well as politics. However, despite the bloodshed and warfare, the Regency was also a period of great refinement and cultural achievement, which shaped and altered the societal structure of Britain as a whole.

One of the greatest patrons of the arts and architecture was the Prince Regent himself (the future George IV). Upper-class society flourished in a sort of mini-Renaissance of culture and refinement. As one of the greatest patrons of the arts, the Prince Regent ordered the costly building and refurbishing of the beautiful and exotic Brighton Pavilion, the ornate Carlton House, as well as many other public works and architecture (see John Nash, James Burton, and Decimus Burton). Naturally, this required dipping into the treasury, and the Regent, and later, the King's exuberance often outstripped his pocket, at the people's expense.[3]

Society during that period was considerably stratified. In many ways, there was a dark counterpart to the beautiful and fashionable sectors of England of this time. In the dingier, less affluent areas of London, thievery, womanising, gambling, the existence of rookeries, and constant drinking ran rampant.[4] The population boom—comprising an increase from just under a million in 1801 to one and a quarter million by 1820[4]—created a wild, roiling, volatile, and vibrant scene. According to Robert Southey, the difference between the strata of society was vast indeed:

The squalor that existed beneath the glamour and gloss of Regency society provided sharp contrast to the Prince Regent's social circle. Poverty was addressed only marginally. The formation of the Regency after the retirement of George III saw the end of a more pious and reserved society, and gave birth of a more frivolous, ostentatious one. This change was influenced by the Regent himself, who was kept entirely removed from the machinations of politics and military exploits. This did nothing to channel his energies in a more positive direction, thereby leaving him with the pursuit of pleasure as his only outlet, as well as his sole form of rebellion against what he saw as disapproval and censure in the form of his father.[5]

Driving these changes were not only money and rebellious pampered youth, but also significant technological advancements. In 1814, The Times adopted steam printing. By this method it could now print 1,100 sheets every hour, not 200 as before—a fivefold increase in production capability and demand.[6] This development brought about the rise of the wildly popular fashionable novels in which publishers spread the stories, rumours, and flaunting of the rich and aristocratic, not so secretly hinting at the specific identity of these individuals. The gap in the hierarchy of society was so great that those of the upper classes could be viewed by those below as wondrous and fantastical fiction, something entirely out of reach yet tangibly there.

Events[]

- 1811

- George Augustus Frederick, Prince of Wales,[7] began his nine-year tenure as regent and became known as The Prince Regent. This sub-period of the Georgian era began the formal Regency. The Duke of Wellington held off the French at Fuentes de Oñoro and Albuhera in the Peninsular War. The Prince Regent held a fête at 9:00 p.m. 19 June 1811, at Carlton House in celebration of his assumption of the Regency. Luddite uprisings. Glasgow weavers riot.

- 1812

- Prime Minister Spencer Perceval was assassinated in the House of Commons. The final shipment of the Elgin Marbles arrived in England. Sarah Siddons retired from the stage. Shipping and territory disputes started the War of 1812 between the United Kingdom and the United States. The British were victorious over French armies at the Battle of Salamanca. Gas company (Gas Light and Coke Company) founded. Charles Dickens, English writer and social critic of the Victorian era, was born on 7 February 1812.

- 1813

- Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen was published. William Hedley's Puffing Billy, an early steam locomotive, ran on smooth rails. Quaker prison reformer Elizabeth Fry started her ministry at Newgate Prison. Robert Southey became Poet Laureate.

- 1814

- Invasion of France by allies led to the Treaty of Paris, ended one of the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon abdicated and was exiled to Elba. The Duke of Wellington was honoured at Burlington House in London. British soldiers burn the White House. Last River Thames Frost Fair was held, which was the last time the river froze. Gas lighting introduced in London streets.

Wellington at the Battle of Waterloo

Wellington at the Battle of Waterloo - 1815

- Napoleon I of France defeated by the Seventh Coalition at the Battle of Waterloo. Napoleon was exiled to St. Helena. The English Corn Laws restricted corn imports. Sir Humphry Davy patented the miners' safety lamp. John Loudon Macadam's road construction method adopted.

- 1816

- Income tax abolished. A "year without a summer" followed a volcanic eruption in Indonesia. Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein. William Cobbett published his newspaper as a pamphlet. The British returned Indonesia to the Dutch. Regent's Canal, London, phase one of construction. Beau Brummell escaped his creditors by fleeing to France.

- 1817

- Antonin Carême created a spectacular feast for the Prince Regent at the Royal Pavilion in Brighton. The death of Princess Charlotte (the Prince Regent's daughter) from complications of childbirth changed obstetrical practices. Elgin Marbles shown at the British Museum. Captain Bligh died.

- 1818

- Queen Charlotte died at Kew. Manchester cotton spinners went on strike. Riot in Stanhope, County Durham between lead miners and the Bishop of Durham's men over Weardale game rights. Piccadilly Circus constructed in London. Frankenstein published. Emily Brontë born.

- 1819

- Peterloo Massacre. Princess Alexandrina Victoria (future Queen Victoria) was christened in Kensington Palace. Ivanhoe by Walter Scott was published. Sir Stamford Raffles, a British administrator, founded Singapore. First steam-propelled vessel (the SS Savannah) crossed the Atlantic and arrived in Liverpool from Savannah, Georgia.

- 1820

- Death of George III and the accession of The Prince Regent as George IV. The House of Lords passed a bill to grant George IV a divorce from Queen Caroline, but because of public pressure, the bill was dropped. John Constable began work on The Hay Wain. Cato Street Conspiracy failed. Royal Astronomical Society founded. Venus de Milo discovered.

Places[]

The following is a list of places associated with the Regency era:[8]

- The Adelphi Theatre[9]

- Almack's

- Angelo's, a fencing parlor

- Astley's Amphitheatre

- Attingham Park[10]

- Bath, Somerset[11]

- Brighton Pavilion

- Brighton and Hove

- Brooks's

- Burlington Arcade

- Bury St Edmunds

- Carlton House, London

- Chapel Royal, St. James's

- Cheltenham, Gloucestershire[12]

- Circulating libraries, 1801–25[13]

- Covent Garden

- Custom Office, London Docks

- Doncaster Races[14]

- Drury Lane

- Floris of London

- Fortnum & Mason

- Gretna Green[15]

- Gentleman Jackson's Saloon, a pugilist's parlor by bare-knuckle champion John Jackson

- Hatchard's

- Little Theatre, Haymarket

- Her Majesty's Theatre

- Holland House

- Houses of Parliament

- Hyde Park, London

- Jermyn Street

- Kensington Gardens[16]

- King of Clubs (Whig club)

- List of London's gentlemen's clubs

- Lloyd's of London

- London Institution

- London Post Office[15]

- Lyme Regis

- Marshalsea, closed in 1811, new site opened in 1811 where White Lion Prison had been. Primarily a debtors' prison, also housed seditionists and political prisoners

- Mayfair, London

- Newgate Prison

- Newmarket Racecourse

- The Old Bailey

- Old Bond Street

- Opera House[17]

- Pall Mall, London

- The Pantheon

- Ranelagh Gardens

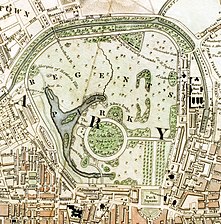

- Regent's Park

- Regent Street

- Royal Circus[17]

- Royal Opera House

- Royal Parks of London

- Rundell and Bridge Jewellery firm

- Savile Row

- St George's, Hanover Square

- St. James's

- Sydney Gardens, Bath[16]

- Temple of Concord, St. James's Park

- Tattersalls

- The Thames Tunnel

- Tunbridge Wells

- Vauxhall Gardens

- West End of London

- Watier's

- White's

Notable people[]

For more names see Newman (1997).[18]

- Rudolph Ackermann

- Arthur Aikin

- Henry Addington, 1st Viscount Sidmouth

- William Arden, 2nd Baron Alvanley

- Elizabeth Armistead

- Jane Austen

- Charles Babbage

- Joseph Banks

- Richard Barry, 7th Earl of Barrymore

- William Blake

- Beau Brummell

- Mary Brunton

- Lord Frederick Beauclerk

- Henrietta Ponsonby, Countess of Bessborough

- Marguerite Gardiner, Countess of Blessington

- Bow Street Runners

- Caroline of Brunswick

- Frances Burney

- James Burton

- Decimus Burton

- Lord Byron

- George Campbell, 6th Duke of Argyll

- Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh

- George Canning

- George Cayley

- Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire

- Princess Charlotte Augusta of Wales

- John Clare

- William Cobbett

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge

- Patrick Colquhoun

- John Constable

- Elizabeth Conyngham, Marchioness Conyngham

- Tom Cribb

- George Cruikshank

- John Dalton

- Humphry Davy

- John Disney

- David Douglas

- Maria Edgeworth

- Pierce Egan

- Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin

- Grace Elliott

- Maria Fitzherbert

- Elizabeth Fry

- David Garrick

- George IV of the United Kingdom, Prince of Wales, Prince Regent then King

- James Gillray

- Frederick Robinson, 1st Viscount Goderich

- William Grenville, 1st Baron Grenville

- Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey

- Emma, Lady Hamilton

- William Harcourt, 3rd Earl Harcourt

- William Hazlitt

- William Hedley

- Leigh Hunt

- Isabella Ingram-Seymour-Conway, Marchioness of Hertford

- John Jackson

- Edward Jenner

- Sarah, Countess of Jersey

- Edmund Kean

- John Keats

- Lady Caroline Lamb

- Charles Lamb

- Emily Lamb, Countess Cowper

- Sir Thomas Lawrence, PRA

- Princess Lieven

- Mary Linwood

- Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool

- Ada Byron Lovelace

- John Loudon McAdam

- Lord Melbourne

- Hannah More

- John Nash

- Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson

- George Ormerod

- Henry Paget, 1st Marquess of Anglesey

- Thomas Paine

- John Palmer, Royal Mail

- Sir Robert Peel

- Spencer Perceval

- William Pitt the Younger

- Jane Porter

- Hermann, Fürst von Pückler-Muskau

- Thomas De Quincey

- Thomas Raikes

- Humphry Repton

- Samuel Rogers

- Thomas Rowlandson

- James Sadler

- Walter Scott

- Richard "Conversation" Sharp

- Percy Bysshe Shelley

- Mary Shelley

- Richard Brinsley Sheridan

- Sarah Siddons

- John Soane

- Adam Sedgwick

- Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh

- John Wedgwood

- Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

- Amelia Stewart, Viscountess Castlereagh

- Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford

- Joseph Mallord William Turner

- Henry Vassall-Fox, 3rd Baron Holland

- Benjamin West

- William Wilberforce

- William Hyde Wollaston

- Mary Wollstonecraft

- William Wordsworth

- Jeffry Wyattville

- Thomas Young

Newspapers, pamphlets, and publications[]

- Ackermann's Repository

- The Gentleman's Magazine

- British Journalists 1750–1820[19]

- Newspapers in the Regency era[20]

- The Times

- The Observer

- Weekly Political Register, William Cobbett

- La Belle Assemblée

Gallery[]

"Neckclothitania", 1818

Astley's Amphitheatre, 1808-1811

Brighton Pavilion, 1826

Carlton House, Pall Mall London.

Vauxhall Gardens, 1808–1811

Church of All Souls, architect John Nash, 1823

Regent's Canal, Limehouse, 1823

Frost Fair, Thames River, 1814

The Piccadilly entrance to the Burlington Arcade, 1819

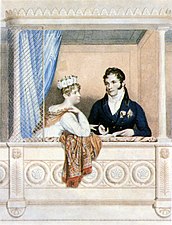

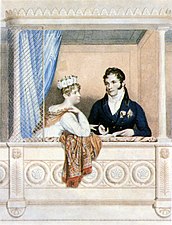

Princess Charlotte Augusta of Wales and Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, 1817

Morning dress, Ackermann, 1820

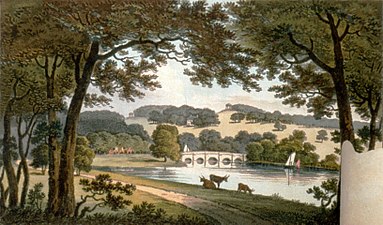

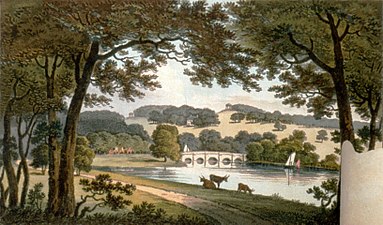

Water at Wentworth, Humphry Repton, 1752–1818

Hanover Square, Horwood Map, 1819

Beau Brummell, 1805

Battle of Waterloo, 1815

Almack's Assembly Room, 1805–1825

Drury Lane interior. 1808

Balloon ascent, James Sadler, 1811

The Anatomist, Thomas Rowlandson, 1811

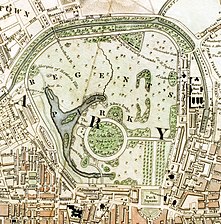

Regent's Park, Schmollinger map, 1833

100 Pall Mall, former location of National Gallery, 1824–1834

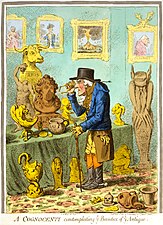

Cognocenti, Gillray Cartoon, 1801

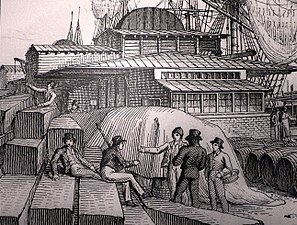

Custom Office, London Docks, 1811-1843

Custom and Excise, London Docks, 1820

Mail coach, 1827

Assassination of Spencer Perceval, 1812

The pillory at Charing Cross, Ackermann's Microcosm of London, 1808–11

Covent Garden Theatre, 1827–28

See also[]

- Regency architecture

- Regency fashions

- Regency dance

- Régence, the period of the early 18th-century regency in France

- Society of Dilettanti

References[]

- ^ Pryde, E. B. (23 February 1996). Handbook of British Chronology. Cambridge University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-521-56350-5.

- ^ Dabundo, Laura; Mazzeno, Laurence W.; Norton, Sue (2021). Jane Austen: A Companion. McFarland. p. 177.

- ^ Parissien, Steven. (2001). George IV: Inspiration of the Regency. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 117.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Low, Donald A. (1999). The Regency Underworld. Gloucestershire: Sutton. p. x.

- ^ Smith p. 14.

- ^ Morgan, Marjorie. (1994). Manners, Morals, and Class in England, 1774–1859. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 34.

- ^ "George IV (r. 1820–1830)". The Royal Household. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ * Gerald Newman, ed. (1997). Britain in the Hanoverian Age, 1714-1837: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780815303961.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ Nelson, Alfred L.; Cross, Gilbert B. "The Adelphi Theatre, 1806–1900". Archived from the original on 8 June 2007.

- ^ "Attingham Park: History". National Trust. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ "Roman, Regency and really nearby". 14 April 2006 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ StephanieSanders (6 December 2013). "Explore the Regency spa town of Cheltenham". visitengland.com.

- ^ "Circulating Libraries, 1801–1825". Library History Database. Archived from the original on 14 April 2008. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ "Jane Austen: Sports". Jane's Bureau of Information. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Jane Austen: Places". Jane's Bureau of Information. Archived from the original on 8 May 2008. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Jane Austen: Gardens". Jane's Bureau of Information. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Jane Austen: Theatre". Jane's Bureau of Information. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ Gerald Newman, ed. (1997). Britain in the Hanoverian Age, 1714-1837: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780815303961.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ "British Journalists 1750–1820". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ "Newspapers and publishers at dawn of 19th century". Georgian Index. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

Further reading[]

- Bowman, Peter James. The Fortune Hunter: A German Prince in Regency England. Oxford: Signal Books, 2010.

- David, Saul. Prince of Pleasure The Prince of Wales and the Making of the Regency. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1998.

- Knafla, David, Crime, punishment, and reform in Europe, Greenwood Publishing, 2003

- Lapp, Robert Keith. Contest for Cultural Authority – Hazlitt, Coleridge, and the Distresses of the Regency. Detroit: Wayne State UP, 1999.

- Marriott, J. A. R. England Since Waterloo (1913) online

- Morgan, Marjorie. Manners, Morals, and Class in England, 1774–1859. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1994.

- Morrison, Robert. The Regency Years: During Which Jane Austen Writes, Napoleon Fights, Byron Makes Love, and Britain Becomes Modern. 2019, New York: W. W. Norton, London: Atlantic Books online review

- Newman, Gerald, ed. (1997). Britain in the Hanoverian Age, 1714-1837: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780815303961.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) online review; 904pp; 1121 short articles on Britain by 250 experts

- Parissien, Steven. George IV Inspiration of the Regency. New York: St. Martin's P, 2001.

- Pilcher, Donald. The Regency Style: 1800–1830 (London: Batsford, 1947).

- Rendell, Jane. The pursuit of pleasure: gender, space & architecture in Regency London (Bloomsbury, 2002).

- Smith, E. A. George IV. (Yale UP, 1999).

- Webb, R.K. Modern England: from the 18th century to the present (1968) online widely recommended university textbook

- Wellesley, Lord Gerald. "Regency Furniture", The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 70, no. 410 (1937): 233–41.

- White, R.J. Life in Regency England (Batsford, 1963).

Crime and punishment[]

- Emsley, Clive. Crime and society in England: 1750-1900 (2013).

- Innes, Joanna and John Styles. "The Crime Wave: Recent Writing on Crime and Criminal Justice in Eighteenth-Century England" Journal of British Studies 25#4 (1986), pp. 380–435 [https://www.jstor.org/stable/175563 online.

- Low, Donald A. The Regency Underworld. Gloucestershire: Sutton, 1999.

- Morgan, Gwenda, and Peter Rushton. Rogues, Thieves And the Rule of Law: The Problem Of Law Enforcement In North-East England, 1718-1820 (2005).

Primary sources[]

- Simond, Louis. Journal of a tour and residence in Great Britain, during the years 1810 and 1811 online

External links[]

- Greenwood's Map of London, 1827

- Horwood Map of London, 1792 – 1799

- Results of the 1801 and 1811 Census of London, The European Magazine and London Review, 1818, p. 50

- The Bluestocking Archive

- End of an Era: 1815–1830

- New York Public Library, England – The Regency Style

- Regency Style Furniture

- Regency era

- Regency London

- 1810s in the United Kingdom

- George III of the United Kingdom

- George IV of the United Kingdom

- History of the United Kingdom by period

- Historical eras

- London architecture

- Regency (government)

- 1820 in the United Kingdom

- 1830s in the United Kingdom