Retinol

| |

Retinol | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data | |

| Routes of administration | by mouth, IM[1] |

| Drug class | vitamin |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.621 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

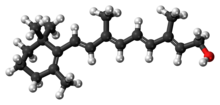

| Formula | C20H30O |

| Molar mass | 286.4516 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 62–64 °C (144–147 °F) |

| Boiling point | 137–138 °C (279–280 °F) (10−6 mm Hg) |

Retinol, also called vitamin A1, is a vitamin in the vitamin A family[1] found in food and used as a dietary supplement.[2] As a supplement it is used to treat and prevent vitamin A deficiency, especially that which results in xerophthalmia.[1] In regions where deficiency is common, a single large dose is recommended to those at high risk twice a year.[3] It is also used to reduce the risk of complications in measles patients.[3] It is taken by mouth or by injection into a muscle.[1]

Retinol at normal doses is well tolerated.[1] High doses may cause enlargement of the liver, dry skin, and hypervitaminosis A.[1][4] High doses during pregnancy may harm the fetus.[1] The body coverts retinol to retinal and retinoic acid, through which it acts.[2] Dietary sources include fish, dairy products, and meat.[2]

Retinol was discovered in 1909, isolated in 1931, and first made in 1947.[5][6] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[7] Retinol is available as a generic medication and over the counter.[1]

Medical uses[]

Retinol is used to treat vitamin A deficiency.

Three approaches may be used when populations have low vitamin A levels:[8]

- Through dietary modification involving the adjustment of menu choices of affected persons from available food sources to optimize vitamin A content.

- Enriching commonly eaten and affordable foods with vitamin A, a process called fortification. It involves addition of synthetic vitamin A to staple foods like margarine, bread, flours, cereals and other infant formulae during processing

- By giving high-doses of vitamin A to the targeted deficient population, a method known as supplementation.

Side effects[]

The Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) for vitamin A, for a 25-year-old man, is 3,000 micrograms/day, or about 10,000 IU. In breastfeeding mothers, vitamin A intake should be 1,200 to 1,300 retinol activity units (RAE).[9]

Too much vitamin A in retinoid form can cause harmful or fatal hypervitaminosis A. The body converts the dimerized form, carotene, into vitamin A as it is needed, so high levels of carotene are not toxic, whereas the ester (animal) forms are. The livers of certain animals, especially those adapted to polar environments, such as polar bears and seals,[10] often contain amounts of vitamin A that would be toxic to humans. Thus, vitamin A toxicity is typically reported in Arctic explorers and people taking large doses of synthetic vitamin A. The first documented death possibly caused by vitamin A poisoning was that of Xavier Mertz, a Swiss scientist, who died in January 1913 on an Antarctic expedition that had lost its food supplies and fell to eating its sled dogs. Mertz may have consumed lethal amounts of vitamin A by eating the dogs' livers.[11]

Vitamin A acute toxicity occurs when a person ingests vitamin A in large amounts more than the daily recommended value in the threshold of 25,000 IU/kg or more. Often, the sufferer consumes about 3–4 times the RDA's specification.[12] Toxicity of vitamin A is believed to be associated with the methods of increasing vitamin A in the body, such as food modification, fortification, and supplementation, all of which are used to combat vitamin A deficiency.[13] Toxicity is classified into two categories: acute and chronic. The former occurs a few hours or days after ingestion of a large amount of vitamin A. Chronic toxicity takes place when about 4,000 IU/kg or more of vitamin A is consumed for a long time. Symptoms of both include nausea, blurred vision, fatigue, weight-loss, and menstrual abnormalities.[14]

Excess vitamin A is suspected to be a contributor to osteoporosis. This seems to happen at much lower doses than those required to induce acute intoxication. Only preformed vitamin A can cause these problems, because the conversion of carotenoids into vitamin A is downregulated when physiological requirements are met; but excessive uptake of carotenoids can cause carotenosis.

Dietary supplementation with beta carotene was associated with an increase in lung cancer when it was studied in a trial of lung-cancer prevention in male smokers. In non-smokers, the opposite effect has been noted.[citation needed]

Excess preformed vitamin A during early pregnancy is associated with a significant increase in birth defects.[15] These defects may be severe, even life-threatening. Even twice the daily recommended amount can cause severe birth defects.[16] The FDA recommends that pregnant women get their vitamin A from foods containing beta carotene and that they ensure that they consume no more than 5,000 IU of preformed vitamin A (if any) per day. Although vitamin A is necessary for fetal development, most women carry stores of vitamin A in their fat cells, so over-supplementation should be strictly avoided.

A review of all randomized controlled trials in the scientific literature by the Cochrane Collaboration published in JAMA in 2007 found that supplementation with beta carotene or vitamin A increased mortality by 5% and 16%, respectively.[17]

Contrary to earlier observations, recent studies emerging from some developing countries (India, Bangladesh, and Indonesia) have strongly suggested that, in populations in which vitamin A deficiency is common and maternal mortality is high, dosing expectant mothers can greatly reduce maternal mortality.[18] Similarly, dosing newborn infants with 50,000 IU (15 mg) of vitamin A within two days of birth can significantly reduce neonatal mortality.[19][20]

Biological role[]

Retinol or other forms of vitamin A are needed for eyesight, maintenance of the skin, and human development.[1]

Embryology[]

Retinoic acid via the retinoic acid receptor influences the process of cell differentiation, hence, the growth and development of embryos. During development, there is a concentration gradient of retinoic acid along the anterior-posterior (head-tail) axis. Cells in the embryo respond to retinoic acid differently depending on the amount present. For example, in vertebrates, the hindbrain transiently forms eight rhombomeres and each rhombomere has a specific pattern of genes being expressed. If retinoic acid is not present the last four rhombomeres do not develop. Instead, rhombomeres 1–4 grow to cover the same amount of space as all eight would normally occupy. Retinoic acid has its effects by turning on a differential pattern of Homeobox (Hox) genes that encode different homeodomain transcription factors which in turn can turn on cell type specific genes. Deletion of the Homeobox (Hox-1) gene from rhombomere 4 makes the neurons growing in that region behave like neurons from rhombomere 2. Retinoic acid is not required for patterning of the retina as originally proposed, but retinoic acid synthesized in the retina is secreted into surrounding mesenchyme where it is required to prevent overgrowth of perioptic mesenchyme which can cause microphthalmia, defects in the cornea and eyelid, and rotation of the optic cup.[21]

Stem cell biology[]

Retinoic acid is an influential factor used in differentiation of stem cells to more committed fates, echoing retinoic acid's importance in natural embryonic developmental pathways. It is thought to initiate differentiation into a number of different cell lineages by unsequestering certain sequences in the genome.

It has numerous applications in the experimental induction of stem cell differentiation; amongst these are the differentiation of human embryonic stem cells to posterior foregut lineages and also to functional motor neurons.

Vision[]

Vitamin A is converted by the protein RPE65 within the retinal pigment epithelium into 11-cis-retinal. This molecule is then transported into the photoreceptor cells of the retina, where it acts as a light-activated molecular switch within opsin proteins that activates a complex cascade called the visual cycle. This cycle begins with 11-cis retinal absorbing light and isomerizing into all-trans retinal. The change in shape of the molecule after absorbing light in turn changes the configuration of the complex protein rhodopsin, the visual pigment used in low light levels.[citation needed] This represents the first step of the visual cycle. This is why eating foods rich in vitamin A is often said to allow an individual to see in the dark, although the effect they have on one's vision is negligible.

Glycoprotein synthesis[]

Glycoprotein synthesis requires adequate vitamin A status. In severe vitamin A deficiency, lack of glycoproteins may lead to corneal ulcers or liquefaction.[22]

Immune system[]

Vitamin A is essential to maintain intact epithelial tissues as a physical barrier to infection; it is also involved in maintaining a number of immune cell types from both the innate and acquired immune systems.[23] These include the lymphocytes (B-cells, T-cells, and natural killer cells), as well as many myelocytes (neutrophils, macrophages, and myeloid dendritic cells).

Red blood cells[]

Vitamin A may be needed for normal red blood cell formation;[24][25] deficiency causes abnormalities in iron metabolism.[26] Vitamin A is needed to produce the red blood cells from stem cells through retinoid differentiation.[27]

Growth[]

Vitamin A affects the production of human growth hormone.[28] Retinoic acid is required to bind to nuclear receptors to aid in growth.[28]

Units of measurement[]

When referring to dietary allowances or nutritional science, retinol is usually measured in international units (IU). IU refers to biological activity and therefore is unique to each individual compound, however 1 IU of retinol is equivalent to approximately 0.3 micrograms (300 nanograms).

Nutrition[]

| Vitamin properties | |

|---|---|

| Solubility | Fat |

| RDA (adult male) | 900 µg/day |

| RDA (adult female) | 700 µg/day |

| RDA upper limit (adult male) | 3,000 µg/day |

| RDA upper limit (adult female) | 3,000 µg/day |

| Deficiency symptoms | |

| |

| Excess symptoms | |

| |

| Common sources | |

| |

This vitamin plays an essential role in vision, particularly night vision, normal bone and tooth development, reproduction, and the health of skin and mucous membranes (the mucus-secreting layer that lines body regions such as the respiratory tract). Vitamin A also acts in the body as an antioxidant, a protective chemical that may reduce the risk of certain cancers.

There are two sources of dietary vitamin A. Active forms, which are immediately available to the body are obtained from animal products. These are known as retinoids and include retinaldehyde and retinol. Precursors, also known as provitamins, which must be converted to active forms by the body, are obtained from fruits and vegetables containing yellow, orange and dark green pigments, known as carotenoids, the most well-known being β-carotene. For this reason, amounts of vitamin A are measured in Retinol Equivalents (RE). One RE is equivalent to 0.001 mg of retinol, or 0.006 mg of β-carotene, or 3.3 International Units of vitamin A.

In the intestine, vitamin A is protected from being chemically changed by vitamin E. Vitamin A is fat-soluble and can be stored in the body. Most of the vitamin A consumed is stored in the liver. When required by a particular part of the body, the liver releases some vitamin A, which is carried by the blood and delivered to the target cells and tissues.

Dietary intake[]

The Dietary Reference Intake (DRI) Recommended Daily Amount (RDA) for vitamin A for a 25-year-old male is 900 micrograms/day, or 3000 IU. NHS daily recommended values are slightly lower at 700 micrograms for men and 600 micrograms for women.[29]

Estimates have changed over time of the rate at which β-carotene is converted to vitamin A in the human body. An early estimate of 6:1 was revised to 12:1 and from recent studies and experimental trials carried out in developing nations it was revised again to 21:1.[18] The implication of the reduced estimate is that larger quantities of β-carotene are needed to yield the necessary dietary requirement of vitamin A. This means that more continents are affected by the deficiency of vitamin A than was previously thought. Changing dietary choices in Africa, Asia, and South America will not be sufficient, and agricultural practices on those continents will need to change.[18]

The Food Standards Agency states that an average adult should not consume more than 1500 micrograms (5000 IU) per day, because this increases the chance of osteoporosis.

During the absorption process in the intestines, retinol is incorporated into chylomicrons as the ester form, and it is these particles that mediate transport to the liver. Liver cells (hepatocytes) store vitamin A as the ester, and when retinol is needed in other tissues, it is de-esterifed and released into the blood as the alcohol. Retinol then attaches to a serum carrier, retinol binding protein, for transport to target tissues. A binding protein inside cells, , serves to store and move retinoic acid intracellularly. Carotenoid bioavailability is 1⁄10 to 1⁄5 that of retinol. Carotenoids are better absorbed when ingested as part of a fatty meal. Also, the carotenoids in vegetables, especially those with tough cell walls (e.g. carrots), are better absorbed when these cell walls are broken up by cooking or mincing.

Deficiency[]

Vitamin A deficiency is common in developing countries but rarely seen in developed countries. Approximately 250,000 to 500,000 malnourished children in the developing world go blind each year from a deficiency of vitamin A.[30] Vitamin A deficiency in expecting mothers increases the mortality rate of children shortly after childbirth.[31] Night blindness is one of the first signs of vitamin A deficiency. Vitamin A deficiency contributes to blindness by making the cornea very dry and damaging the retina and cornea.[32]

Sources[]

Retinoids are found naturally only in foods of animal origin. Each of the following contains at least 0.15 mg of retinoids per 1.75–7 oz (50–198 g):

- Cod liver oil

- Butter

- Liver (beef, pork, chicken, turkey, fish)

- Eggs

- Cheese, Milk[33]

Synthetic sources[]

Synthetic retinol is marketed under the following trade names: Acon, Afaxin, Agiolan, Alphalin, Anatola, Aoral, Apexol, Apostavit, Atav, Avibon, Avita, Avitol, Axerol, Dohyfral A, Epiteliol, Nio-A-Let, Prepalin, Testavol, Vaflol, Vi-Alpha, Vitpex, Vogan, and Vogan-Neu.

There are three known routes to retinol that are used industrially, all of which start with β-ionone.[34]

Night vision[]

Night blindness—the inability to see well in dim light—is associated with a deficiency of vitamin A. At first, the most light sensitive (containing more retinal) protein rhodopsin is influenced. Less pigmented retinal iodopsins (three forms/colors in humans), responsible for color vision and sensing relatively high light intensities (day vision), are less impaired at early stages of the vitamin A deficiency. All these protein-pigment complexes are located in the light-sensing cells in eye's retina.

When stimulated by light, rhodopsin splits into a protein and a cofactor: opsin and all-trans-retinal (a form of vitamin A). The regeneration of active rhodopsin requires opsin and 11-cis-retinal. The regeneration of 11-cis-retinal occurs in vertebrates via a sequence of chemical transformations that constitute "the visual cycle" and which occurs primarily in the retinal pigmented epithelial cells.

Without adequate amounts of retinol, regeneration of rhodopsin is incomplete and night blindness occurs.

Chemistry[]

Many different geometric isomers of retinol, retinal and retinoic acid are possible as a result of either a trans or cis configuration of four of the five double bonds found in the polyene chain. The cis isomers are less stable and can readily convert to the all-trans configuration (as seen in the structure of all-trans-retinol shown at the top of this page). Nevertheless, some cis isomers are found naturally and carry out essential functions. For example, the 11-cis-retinal isomer is the chromophore of rhodopsin, the vertebrate photoreceptor molecule. Rhodopsin is composed of the 11-cis-retinal covalently linked via a Schiff base to the opsin protein (either rod opsin or blue, red or green cone opsins). The process of vision relies on the light-induced isomerisation of the chromophore from 11-cis to all-trans resulting in a change of the conformation and activation of the photoreceptor molecule. One of the earliest signs of vitamin A deficiency is night-blindness followed by decreased visual acuity.

George Wald won the 1967 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work with retina pigments (also called visual pigments), which led to the understanding of the role of vitamin A in vision.

Many of the non-visual functions of vitamin A are mediated by retinoic acid, which regulates gene expression by activating nuclear retinoic acid receptors.[21] The non-visual functions of vitamin A are essential in the immunological function, reproduction and embryonic development of vertebrates as evidenced by the impaired growth, susceptibility to infection and birth defects observed in populations receiving suboptimal vitamin A in their diet.

Biosynthesis[]

Retinol is synthesized from the breakdown of β-carotene. First, the cleaves β-carotene at the central double bond, creating an epoxide. This epoxide is then attacked by water creating two hydroxyl groups in the center of the structure. The cleavage occurs when these alcohols are reduced to the aldehydes using NADH. This compound is called retinal. Retinal is then reduced to retinol by the enzyme retinol dehydrogenase. Retinol dehydrogenase is an enzyme that is dependent on NADH.[35]

History[]

In 1913, Elmer McCollum, a biochemist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, and colleague Marguerite Davis identified a fat-soluble nutrient in butterfat and cod liver oil. Their work confirmed that of Thomas Burr Osborne (1859-1929) and Lafayette Mendel (1872-1935), at Yale, which suggested a fat-soluble nutrient in butterfat, also in 1913.[36] Vitamin A1 was first synthesized in 1947 by two Dutch chemists, David Adriaan van Dorp (1915-1995) and Jozef Ferdinand Arens (1914-2001).

Although vitamin A was not identified until the 20th century, written observations of conditions created by deficiency of this nutrient appeared much earlier in history. Sommer (2008) classified historical accounts related to vitamin A and/or manifestations of deficiency as follows: "ancient" accounts; 18th- to 19th-century clinical descriptions (and their purported etiologic associations); early 20th-century laboratory animal experiments, and clinical and epidemiologic observations that identified the existence of this unique nutrient and manifestations of its deficiency.[18]

During World War II, German bomber aircraft attacked Britain at night rather than by day to avoid detection, but British interceptor aircraft used the Airborne Intercept Radar (AI) system, developed in 1939, to locate bombers they could not see. To keep AI secret from the German military, the Ministry of Information told newspapers that the good night-time performance of Royal Air Force pilots was due to a high dietary intake of carrots rich in vitamin A, propagating the myth that carrots enable people to see better in the dark.[37]

Manufacture[]

This section does not cite any sources. (November 2020) |

Commercial production of retinol typically requires retinal synthesis through reduction of a pentadiene derivative and subsequent acidification and hydrolysis of the resulting isomer to produce retinol. Pure retinol is extremely sensitive to oxidization and is prepared and transported at low temperatures and oxygen free atmospheres. When prepared as a dietary supplement, retinol is stabilized as the ester derivatives retinyl acetate or retinyl palmitate.

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j "Vitamin A". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Office of Dietary Supplements - Vitamin A". ods.od.nih.gov. 31 August 2016. Archived from the original on 12 December 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. p. 500. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- ^ British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. p. 701. ISBN 9780857111562.

- ^ Squires VR (2011). The Role of Food, Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries in Human Nutrition - Volume IV. EOLSS Publications. p. 121. ISBN 9781848261952. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017.

- ^ Ullmann's Food and Feed, 3 Volume Set. John Wiley & Sons. 2016. p. Chapter 2. ISBN 9783527695522. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ Schultink W (September 2002). "Use of under-five mortality rate as an indicator for vitamin A deficiency in a population". The Journal of Nutrition. 132 (9 Suppl): 2881S–2883S. doi:10.1093/jn/132.9.2881S. PMID 12221264.

- ^ "Vitamin A". National Institutes of Health. 5 October 2018.

- ^ Rodahl K, Moore T (July 1943). "The vitamin A content and toxicity of bear and seal liver". The Biochemical Journal. 37 (2): 166–8. doi:10.1042/bj0370166. PMC 1257872. PMID 16747610.

- ^ Nataraja A. "Man's best friend? (An account of Mertz's illness)". Archived from the original on 29 January 2007.

- ^ Gropper SS, Smith JL, Groff JL (2009). Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism (5th ed.). pp. 373–1182.

- ^ Thompson J, Manore M (2005). "Ch. 8: Nutrients involved in antioxidant function". Nutrition: An Applied Approach. Pearson Education Inc. pp. 276–283.

- ^ Mohsen SE, Mckinney K, Shanti MS (2008). "Vitamin A toxicity". Medscape. Archived from the original on 23 July 2013.

- ^ Challem J (1995). "Caution Urged With Vitamin A in Pregnancy: But Beta-Carotene is Safe". The Nutrition Reporter Newsletter. Archived from the original on 1 September 2004.

- ^ Stone B (6 October 1995). "Vitamin A and Birth Defects". United States FDA. Archived from the original on 4 February 2004.

- ^ Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Gluud LL, Simonetti RG, Gluud C (February 2007). "Mortality in randomized trials of antioxidant supplements for primary and secondary prevention: systematic review and meta-analysis" (PDF). JAMA. 297 (8): 842–57. doi:10.1001/jama.297.8.842. PMID 17327526. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 February 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Sommer A (October 2008). "Vitamin a deficiency and clinical disease: an historical overview". The Journal of Nutrition. 138 (10): 1835–9. doi:10.1093/jn/138.10.1835. PMID 18806089.

- ^ Tielsch JM, Rahmathullah L, Thulasiraj RD, Katz J, Coles C, Sheeladevi S, et al. (November 2007). "Newborn vitamin A dosing reduces the case fatality but not incidence of common childhood morbidities in South India". The Journal of Nutrition. 137 (11): 2470–4. doi:10.1093/jn/137.11.2470. PMID 17951487.

- ^ Klemm RD, Labrique AB, Christian P, Rashid M, Shamim AA, Katz J, et al. (July 2008). "Newborn vitamin A supplementation reduced infant mortality in rural Bangladesh". Pediatrics. 122 (1): e242-50. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-3448. PMID 18595969. S2CID 27427577.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Duester G (September 2008). "Retinoic acid synthesis and signaling during early organogenesis". Cell. 134 (6): 921–31. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.002. PMC 2632951. PMID 18805086.

- ^ Starck T (1997). "Severe Corneal Ulcerations and Vitamin A Deficiency". Advances in Corneal Research. Springer, Boston, MA. p. 558. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-5389-2_46. ISBN 978-1-4613-7460-2.

- ^ "Vitamin A directs immune cells to intestines". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ Oren T, Sher JA, Evans T (November 2003). "Hematopoiesis and retinoids: development and disease". Leukemia & Lymphoma. 44 (11): 1881–91. doi:10.1080/1042819031000116661. PMID 14738139. S2CID 11348076.

- ^ Evans T (September 2005). "Regulation of hematopoiesis by retinoid signaling". Experimental Hematology. 33 (9): 1055–61. doi:10.1016/j.exphem.2005.06.007. PMID 16140154.

- ^ García-Casal MN, Layrisse M, Solano L, Barón MA, Arguello F, Llovera D, et al. (March 1998). "Vitamin A and beta-carotene can improve nonheme iron absorption from rice, wheat and corn by humans". The Journal of Nutrition. 128 (3): 646–50. doi:10.1093/jn/128.3.646. PMID 9482776.

- ^ "Carotenoid Oxygenase". InterPro. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Raifen R, Altman Y, Zadik Z (1996). "Vitamin A levels and growth hormone axis". Hormone Research. 46 (6): 279–81. doi:10.1159/000185101. PMID 9064277.

- ^ Vitamins and minerals – Vitamin A – NHS Choices Archived 2013-09-23 at the Wayback Machine. Nhs.uk (2012-11-26). Retrieved on 2013-09-19.

- ^ "Micronutrient deficiencies - Vitamin A deficiency". World Health Organization. 18 April 2018. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ^ Akhtar S, Ahmed A, Randhawa MA, Atukorala S, Arlappa N, Ismail T, Ali Z (December 2013). "Prevalence of vitamin A deficiency in South Asia: causes, outcomes, and possible remedies". Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition. 31 (4): 413–23. doi:10.3329/jhpn.v31i4.19975. PMC 3905635. PMID 24592582.

- ^ Sommer A (February 1994). "Vitamin A: its effect on childhood sight and life". Nutrition Reviews. 52 (2 Pt 2): S60-6. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.1994.tb01388.x. PMID 8202284.

- ^ Brown, J. E. (2002). Vitamins and Your Health. Nutrition Now. 3rd ed., pp. 20–1 to 20–20.

- ^ Ashford's Dictionary of Industrial Chemicals, 3rd ed., 2011, ISBN 978-0-9522674-3-0, p. 9662

- ^ Dewick, Paul M. (2009), Medicinal Natural Products, Wiley, ISBN 0470741678.

- ^ Semba RD (April 1999). "Vitamin A as "anti-infective" therapy, 1920-1940". The Journal of Nutrition. 129 (4): 783–91. doi:10.1093/jn/129.4.783. PMID 10203551.

- ^ Smith KA (13 August 2013). "A WWII Propaganda Campaign Popularized the Myth That Carrots Help You See in the Dark". Smithsonian.com. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

External links[]

- Jane Higdon, "Vitamin A", Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University

- NIH Office of Dietary Supplements – Vitamin A

- Vitamin A Deficiency at the Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy

- WHO publications on Vitamin A Deficiency

- "Retinol". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Antioxidants

- Apocarotenoids

- Cyclohexenes

- Diterpenes

- Primary alcohols

- Vitamins

- World Health Organization essential medicines