Ribavirin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌraɪbəˈvaɪrɪn/ RY-bə-VY-rin |

| Trade names | Copegus, Rebetol, Virazole, other[1] |

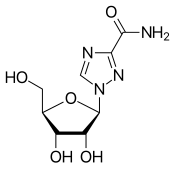

| Other names | 1-(β-D-Ribofuranosyl)-1"H"-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamide, tribavirin (BAN UK) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a605018 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, solution for inhalation |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 64%[2] |

| Protein binding | 0%[2] |

| Metabolism | liver and intracellularly[2] |

| Elimination half-life | 298 hours (multiple dose); 43.6 hours (single dose)[2] |

| Excretion | Urine (61%), faeces (12%)[2] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.164.587 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C8H12N4O5 |

| Molar mass | 244.207 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 166 to 168 °C (331 to 334 °F) |

| |

| |

Ribavirin, also known as tribavirin, is an antiviral medication used to treat RSV infection, hepatitis C and some viral hemorrhagic fevers.[1] For hepatitis C, it is used in combination with other medications such as simeprevir, sofosbuvir, peginterferon alfa-2b or peginterferon alfa-2a.[1] Among the viral hemorrhagic fevers it is used for Lassa fever, Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever, and Hantavirus infection but should not be used for Ebola or Marburg infections.[1] Ribavirin is taken by mouth or inhaled.[1]

Common side effects include feeling tired, headache, nausea, fever, muscle pains, and an irritable mood.[1] Serious side effects include red blood cell breakdown, liver problems, and allergic reactions.[1] Use during pregnancy results in harm to the baby.[1] Effective birth control is recommended for both males and females for at least seven months during and after use.[3] The mechanism of action of ribavirin is not entirely clear.[1]

Ribavirin was patented in 1971 and approved for medical use in 1986.[4] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[5] It is available as a generic medication.[1]

Medical uses[]

Ribavirin is used primarily to treat hepatitis C and viral hemorrhagic fevers (which is an orphan indication in most countries).[6] In this former indication the oral (capsule or tablet) form of ribavirin is used in combination with pegylated interferon alfa,[7][8][9][10] including in people coinfected with hepatitis B, HIV and in the pediatric population.[9][11][12] Statins may improve this combination's efficacy in treating hepatitis C.[13] Ribavirin is the only known treatment for a variety of viral hemorrhagic fevers, including Lassa fever, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, Venezuelan hemorrhagic fever, and Hantavirus infection, although data regarding these infections are scarce and the drug might be effective only in early stages.[14][15][16][17] It is noted by the USAMRIID that "Ribavirin has poor in vitro and in vivo activity against the filoviruses (Ebola[18] and Marburg) and the flaviviruses (dengue, yellow fever, Omsk hemorrhagic fever, and Kyasanur forest disease)"[19] The aerosol form has been used in the past to treat respiratory syncytial virus-related diseases in children, although the evidence to support this is rather weak.[20]

It has been used (in combination with ketamine, midazolam, and amantadine) in treatment of rabies.[21]

Experimental data indicate that ribavirin may have useful activity against canine distemper and poxviruses.[22][23] Ribavirin has also been used as a treatment for herpes simplex virus. One small study found that ribavirin treatment reduced the severity of herpes outbreaks and promoted recovery, as compared with placebo treatment.[24] Another study found that ribavirin potentiated the antiviral effect of acyclovir.[25]

Some interest has been seen in its possible use as a treatment for cancers, especially acute myeloid leukemia.[26][27]

Adverse effects[]

The medication has two FDA "black box" warnings: One raises concerns that use before or during pregnancy by either sex may result in birth defects in the baby, and the other is regarding the risk of red blood cell breakdown.[28]

Ribavirin should not be given with zidovudine because of the increased risk of anemia;[29] concurrent use with didanosine should likewise be avoided because of an increased risk of mitochondrial toxicity.[30]

Mechanisms of action[]

It is a guanosine (ribonucleic) analog used to stop viral RNA synthesis and viral mRNA capping, thus, it is a nucleoside inhibitor. Ribavirin is a prodrug, which when metabolized resembles purine RNA nucleotides. In this form, it interferes with RNA metabolism required for viral replication. Over five direct and indirect mechanisms have been proposed for its mechanism of action.[31] The enzyme inosine triphosphate pyrophosphatase (ITPase) dephosphorylates ribavirin triphosphate in vitro to ribavirin monophosphate, and ITPase reduced enzymatic activity present in 30% of humans potentiates mutagenesis in hepatitis C virus.[32]

RNA viruses[]

Ribavirin's amide group can make the native nucleoside drug resemble adenosine or guanosine, depending on its rotation. For this reason, when ribavirin is incorporated into RNA, as a base analog of either adenine or guanine, it pairs equally well with either uracil or cytosine, inducing mutations in RNA-dependent replication in RNA viruses. Such hypermutation can be lethal to RNA viruses.[33][34]

DNA viruses[]

Neither of these mechanisms explains ribavirin's effect on many DNA viruses, which is more of a mystery, especially given the complete inactivity of ribavirin's 2' deoxyribose analogue, which suggests that the drug functions only as an RNA nucleoside mimic, and never a DNA nucleoside mimic. Ribavirin 5'-monophosphate inhibits cellular inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase, thereby depleting intracellular pools of GTP.[35] [ERROR: the cited paper refers only to an RNA virus and so does not support this section's assertion. A reference to a DNA virus is needed here.]

History[]

Ribavirin was first made in 1972 under the national cancer institute's Virus-Cancer program.[36] This was done by researchers from International Chemical and Nuclear Corporation including Roberts A. Smith, Joseph T. Witkovski and Roland K. Robins.[37] It was reported that ribavirin was active against a variety of RNA and DNA viruses in culture and in animals, without undue toxicity in the context of cancer chemotherapies.[38] By the late 1970s, the Virus-Cancer program was widely considered a failure, and the drug development was abandoned.

Names[]

Ribavirin is the INN and USAN, whereas tribavirin is the BAN. Brand names of generic forms include Copegus, Ribasphere, Rebetol.[1]

Derivatives[]

Ribavirin is possibly best viewed as a ribosyl purine analogue with an incomplete purine 6-membered ring. This structural resemblance historically prompted replacement of the 2' nitrogen of the triazole with a carbon (which becomes the 5' carbon in an imidazole), in an attempt to partly "fill out" the second ring--- but to no great effect. Such 5' imidazole riboside derivatives show antiviral activity with 5' hydrogen or halide, but the larger the substituent, the smaller the activity, and all proved less active than ribavirin.[39] Note that two natural products were already known with this imidazole riboside structure: substitution at the 5' carbon with OH results in pyrazofurin, an antibiotic with antiviral properties but unacceptable toxicity, and replacement with an amino group results in the natural purine synthetic precursor 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside (AICAR), which has only modest antiviral properties.

Taribavirin[]

The most successful ribavirin derivative to date is the 3-carboxamidine derivative of the parent 3-carboxamide, first reported in 1973 by J. T. Witkowski et al.,[40] and now called taribavirin (former names "viramidine" and "ribamidine"). This drug shows a similar spectrum of antiviral activity to ribavirin, which is not surprising as it is now known to be a pro-drug for ribavirin. Taribavirin, however, has useful properties of less erythrocyte-trapping and better liver-targeting than ribavirin. The first property is due to taribavirin's basic amidine group which inhibits drug entry into RBCs, and the second property is probably due to increased concentration of the enzymes which convert amidine to amide in liver tissue.[41] Taribavirin completed phase III human trials in 2012.[42]

See also[]

- Scavenger system

- Favipiravir

References[]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Ribavirin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "PRODUCT INFORMATION REBETOL (RIBAVIRIN) CAPSULES" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Merck Sharp & Dohme (Australia) Pty Limited. 29 April 2013. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. p. 177. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- ^ Fischer, Janos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 504. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ "Rebetol, Ribasphere (ribavirin) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 28 February 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ Paeshuyse J, Dallmeier K, Neyts J (December 2011). "Ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a review of the proposed mechanisms of action". Current Opinion in Virology. 1 (6): 590–8. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2011.10.030. PMID 22440916.

- ^ Flori N, Funakoshi N, Duny Y, Valats JC, Bismuth M, Christophorou D, Daurès JP, Blanc P (March 2013). "Pegylated interferon-α2a and ribavirin versus pegylated interferon-α2b and ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C : a meta-analysis". Drugs. 73 (3): 263–77. doi:10.1007/s40265-013-0027-1. PMID 23436591. S2CID 46334977.

- ^ a b Druyts E, Thorlund K, Wu P, Kanters S, Yaya S, Cooper CL, Mills EJ (April 2013). "Efficacy and safety of pegylated interferon alfa-2a or alfa-2b plus ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 56 (7): 961–7. doi:10.1093/cid/cis1031. PMID 23243171.

- ^ Zeuzem S, Poordad F (July 2010). "Pegylated-interferon plus ribavirin therapy in the treatment of CHC: individualization of treatment duration according to on-treatment virologic response". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 26 (7): 1733–43. doi:10.1185/03007995.2010.487038. PMID 20482242. S2CID 206965239.

- ^ Liu JY, Sheng YJ, Hu HD, Zhong Q, Wang J, Tong SW, Zhou Z, Zhang DZ, Hu P, Ren H (September 2012). "The influence of hepatitis B virus on antiviral treatment with interferon and ribavirin in Asian patients with hepatitis C virus/hepatitis B virus coinfection: a meta-analysis". Virology Journal. 9: 186. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-9-186. PMC 3511228. PMID 22950520.

- ^ Basso M, Parisi SG, Mengoli C, Gentilini V, Menegotto N, Monticelli J, Nicolè S, Cruciani M, Palù G (July–August 2013). "Sustained virological response and baseline predictors in HIV-HCV coinfected patients retreated with pegylated interferon and ribavirin after failing a previous interferon-based therapy: systematic review and meta-analysis". HIV Clinical Trials. 14 (4): 127–39. doi:10.1310/hct1404-127. PMID 23924585. S2CID 207260133.

- ^ Zhu Q, Li N, Han Q, Zhang P, Yang C, Zeng X, Chen Y, Lv Y, Liu X, Liu Z (June 2013). "Statin therapy improves response to interferon alfa and ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Antiviral Research. 98 (3): 373–9. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.04.009. PMID 23603497.

- ^ Steckbriefe seltener und importierter Infektionskrankheiten [Characteristics of rare and imported infectious diseases] (PDF). Berlin: Robert Koch Institute. 2006. ISBN 978-3-89606-095-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-29.

- ^ Ascioglu S, Leblebicioglu H, Vahaboglu H, Chan KA (June 2011). "Ribavirin for patients with Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 66 (6): 1215–22. doi:10.1093/jac/dkr136. PMID 21482564.

- ^ Bausch DG, Hadi CM, Khan SH, Lertora JJ (December 2010). "Review of the literature and proposed guidelines for the use of oral ribavirin as postexposure prophylaxis for Lassa fever". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 51 (12): 1435–41. doi:10.1086/657315. PMC 7107935. PMID 21058912.

- ^ Soares-Weiser K, Thomas S, Thomson G, Garner P (July 2010). "Ribavirin for Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Infectious Diseases. 10: 207. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-10-207. PMC 2912908. PMID 20626907.

- ^ Goeijenbier M, van Kampen JJ, Reusken CB, Koopmans MP, van Gorp EC (November 2014). "Ebola virus disease: a review on epidemiology, symptoms, treatment and pathogenesis". The Netherlands Journal of Medicine. 72 (9): 442–8. PMID 25387613. Archived from the original on 2014-11-29.

- ^ Medical Management of Biological Casualties Handbook. United States Government Printing Office. 2011. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-16-090015-0.

- ^ Ventre K, Randolph AG (January 2007). Ventre K (ed.). "Ribavirin for respiratory syncytial virus infection of the lower respiratory tract in infants and young children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD000181. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000181.pub3. PMID 17253446.

- ^ Hemachudha T, Ugolini G, Wacharapluesadee S, Sungkarat W, Shuangshoti S, Laothamatas J (May 2013). "Human rabies: neuropathogenesis, diagnosis, and management". The Lancet. Neurology. 12 (5): 498–513. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70038-3. PMID 23602163. S2CID 1798889.

- ^ Elia G, Belloli C, Cirone F, Lucente MS, Caruso M, Martella V, Decaro N, Buonavoglia C, Ormas P (February 2008). "In vitro efficacy of ribavirin against canine distemper virus". Antiviral Research. 77 (2): 108–13. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.09.004. PMID 17949825.

- ^ Baker, Robert O.; Bray, Mike; Huggins, John W. (January 2003). "Potential antiviral therapeutics for smallpox, monkeypox and other orthopoxvirus infections". Antiviral Research. 57 (1–2): 13–23. doi:10.1016/S0166-3542(02)00196-1. ISSN 0166-3542. PMID 12615299.

- ^ Bierman SM, Kirkpatrick W, Fernandez H (1981). "Clinical efficacy of ribavirin in the treatment of genital herpes simplex virus infection". Chemotherapy. 27 (2): 139–45. doi:10.1159/000237969. PMID 7009087.

- ^ Pancheva SN (September 1991). "Potentiating effect of ribavirin on the anti-herpes activity of acyclovir". Antiviral Research. 16 (2): 151–61. doi:10.1016/0166-3542(91)90021-I. PMID 1665959.

- ^ Kast RE (November–December 2002). "Ribavirin in cancer immunotherapies: controlling nitric oxide helps generate cytotoxic lymphocyte". Cancer Biology & Therapy. 1 (6): 626–30. doi:10.4161/cbt.310. PMID 12642684. S2CID 24010404.

- ^ Borden KL, Culjkovic-Kraljacic B (October 2010). "Ribavirin as an anti-cancer therapy: acute myeloid leukemia and beyond?". Leukemia & Lymphoma. 51 (10): 1805–15. doi:10.3109/10428194.2010.496506. PMC 2950216. PMID 20629523.

- ^ "Copedgus" (PDF). FDA.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ^ Alvarez D, Dieterich DT, Brau N, Moorehead L, Ball L, Sulkowski MS (October 2006). "Zidovudine use but not weight-based ribavirin dosing impacts anaemia during HCV treatment in HIV-infected persons". Journal of Viral Hepatitis. 13 (10): 683–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00749.x. PMID 16970600. S2CID 21474337.

- ^ Bani-Sadr F, Carrat F, Pol S, Hor R, Rosenthal E, Goujard C, Morand P, Lunel-Fabiani F, Salmon-Ceron D, Piroth L, Pialoux G, Bentata M, Cacoub P, Perronne C (September 2005). "Risk factors for symptomatic mitochondrial toxicity in HIV/hepatitis C virus-coinfected patients during interferon plus ribavirin-based therapy". Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 40 (1): 47–52. doi:10.1097/01.qai.0000174649.51084.46. PMID 16123681. S2CID 9364536.

- ^ Graci JD, Cameron CE (January 2006). "Mechanisms of action of ribavirin against distinct viruses". Reviews in Medical Virology. 16 (1): 37–48. doi:10.1002/rmv.483. PMC 7169142. PMID 16287208.

- ^ Nyström K, Wanrooij PH, Waldenström J, Adamek L, Brunet S, Said J, Nilsson S, Wind-Rotolo M, Hellstrand K, Norder H, Tang KW, Lagging M (October 2018). "Inosine Triphosphate Pyrophosphatase Dephosphorylates Ribavirin Triphosphate and Reduced Enzymatic Activity Potentiates Mutagenesis in Hepatitis C Virus". Journal of Virology. 92 (19): 01087–18. doi:10.1128/JVI.01087-18. PMC 6146798. PMID 30045981.

- ^ Ortega-Prieto AM, Sheldon J, Grande-Pérez A, Tejero H, Gregori J, Quer J, Esteban JI, Domingo E, Perales C (2013). Vartanian J (ed.). "Extinction of hepatitis C virus by ribavirin in hepatoma cells involves lethal mutagenesis". PLOS ONE. 8 (8): e71039. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...871039O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0071039. PMC 3745404. PMID 23976977.

- ^ Crotty S, Cameron C, Andino R (February 2002). "Ribavirin's antiviral mechanism of action: lethal mutagenesis?". Journal of Molecular Medicine. 80 (2): 86–95. doi:10.1007/s00109-001-0308-0. PMID 11907645. S2CID 52851826.

- ^ Leyssen P, De Clercq E, Neyts J (April 2006). "The anti-yellow fever virus activity of ribavirin is independent of error-prone replication". Molecular Pharmacology. 69 (4): 1461–7. doi:10.1124/mol.105.020057. PMID 16421290. S2CID 8158590.

- ^ Snell NJ (August 2001). "Ribavirin--current status of a broad spectrum antiviral agent". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2 (8): 1317–24. doi:10.1517/14656566.2.8.1317. PMID 11585000. S2CID 46564870.

- ^ "Ribavirin History". News-Medical.net. 12 April 2010. Archived from the original on 2016-03-02. Retrieved 2016-02-19.

- ^ Sidwell RW, Huffman JH, Khare GP, Allen LB, Witkowski JT, Robins RK (August 1972). "Broad-spectrum antiviral activity of Virazole: 1-beta-D-ribofuranosyl-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamide". Science. 177 (4050): 705–6. Bibcode:1972Sci...177..705S. doi:10.1126/science.177.4050.705. PMID 4340949. S2CID 43106875.

- ^ Smith RA & Kirkpatrick W (eds.) (1980). "Ribavirin: structure and antiviral activity relationships". Ribavirin: A Broad Spectrum Antiviral Agent. New York: Academic Press. pp. 1–21.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Witkowski JT, Robins RK, Khare GP, Sidwell RW (August 1973). "Synthesis and antiviral activity of 1,2,4-triazole-3-thiocarboxamide and 1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamidine ribonucleosides". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 16 (8): 935–7. doi:10.1021/jm00266a014. PMID 4355593.

- ^ Sidwell RW, Bailey KW, Wong MH, Barnard DL, Smee DF (October 2005). "In vitro and in vivo influenza virus-inhibitory effects of viramidine". Antiviral Research. 68 (1): 10–7. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.06.003. PMID 16087250.

- ^ U.S. National Library of Medicine (2012-06-22). Study of Viramidine to Ribavirin in Patients With Chronic Hepatitis C Who Are Treatment Naive (VISER2) (Report). National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

External links[]

- "Ribavirin". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Anti–RNA virus drugs

- Triazoles

- Merck & Co. brands

- World Health Organization essential medicines

- Virucides

- Anti–hepatitis C agents