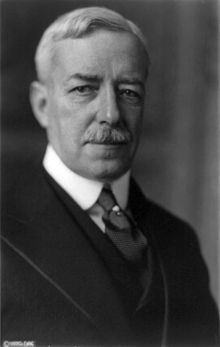

Robert Lansing

Robert Lansing | |

|---|---|

| |

| 42nd United States Secretary of State | |

| In office June 24, 1915 – February 13, 1920 Acting: June 9, 1915 – June 24, 1915 | |

| President | Woodrow Wilson |

| Preceded by | William Jennings Bryan |

| Succeeded by | Bainbridge Colby |

| Counselor of the United States Department of State | |

| In office April 1, 1914 – June 23, 1915 | |

| President | Woodrow Wilson |

| Preceded by | John Bassett Moore |

| Succeeded by | Frank Polk |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 17, 1864 Watertown, New York, U.S. |

| Died | October 30, 1928 (aged 64) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Eleanor Foster (1890–1928) |

| Education | Amherst College (BA) |

Robert Lansing (/ˈlænsɪŋ/; October 17, 1864 – October 30, 1928) was an American lawyer and diplomat who served as Counselor to the State Department at the outbreak of World War I, and then as United States Secretary of State under President Woodrow Wilson from 1915 to 1920. A conservative pro-business Democrat, he was pro-British and a strong defender of American rights at international law. He was a leading enemy of German autocracy and Russian Bolshevism.[1] Before U.S. involvement in the war, Lansing vigorously advocated in favor of the principles of freedom of the seas and the rights of neutral nations. He later advocated U.S. participation in World War I, negotiated the Lansing–Ishii Agreement with Japan in 1917 and was a member of the American Commission to Negotiate Peace at Paris in 1919. However Wilson made Colonel House his chief foreign policy advisor because Lansing privately opposed much of the Versailles treaty and was skeptical of the Wilsonian principle of self-determination.

Career[]

Robert Lansing was born in Watertown, New York, the son of John Lansing (1832–1907) and Maria Lay (Dodge) Lansing. He graduated from Amherst College in 1886, studied law, and was admitted to the bar in 1889.

From then until 1907 he was a member of the law firm of Lansing & Lansing at Watertown. An authority on international law, he served as associate counsel for the United States, during the Bering Sea Arbitration from 1892–1893, as counsel for the United States Bering Sea Claims Commission in 1896–1897, as the government's lawyer before the Alaskan Boundary Tribunal in 1903, as counsel for the North Atlantic Fisheries in the Arbitration at The Hague in 1909–1910, and as agent of the United States in the American and British Arbitration in 1912–1914. In 1914 Lansing was appointed counselor to the State Department by President Woodrow Wilson. Lansing, who had argued cases before Judge Nicholas D. Yost in Watertown, was responsible for encouraging the judge's son, future Ambassador Charles W. Yost, to join the Foreign Service.

World War I[]

Lansing advocated "benevolent neutrality" at the start of World War I, but shifted away from the ideal after increasing interference and violation of the rights of neutrals by Great Britain.[2] Following the sinking of the RMS Lusitania on 7 May 1915 by the German submarine U-20, Lansing backed Woodrow Wilson in issuing three notes of protest to the German government. William Jennings Bryan resigned as Secretary of State following Wilson's second note, which Bryan considered too belligerent. Lansing replaced Bryan, and said in his memoirs that following the Lusitania tragedy he always had the "conviction that we would ultimately become the ally of Britain".

In 1916 Lansing hired a handful of men who became the State Department's first special agents in the new Bureau of Secret Intelligence. These agents were initially used to observe the activities of the Central Powers in America, and later to watch over interned German diplomats. The small group of agents hired by Lansing would eventually become the U.S. Diplomatic Security Service (DSS).

A few weeks before the formal end of World War I, Lansing informed the crumbling Austro-Hungarian Empire that since the Americans were now committed to the causes of the Czechs, Slovaks and South Slavs, the Empire's proposal to satisfy the tenth of Wilson's Fourteen Points by granting the nationalities autonomy within the Empire was no longer sufficient. The declaration of independence of the small nations was read by the president of the Mid-European Union, professor Thomas Garrigue Masaryk. in a Philadelphia congress on 26 October 1918.[3] Within two weeks, these new nations began to declare themselves independent and Austria-Hungary ceased to exist.

Post-World War I[]

In 1919, Lansing became the nominal head of the US Commission to the Paris Peace Conference. Because he did not regard the League of Nations as essential to the peace treaty, Lansing began to fall out of favor with Wilson, for whom participation in the League of Nations was a primary goal. During Wilson's stroke and illness, Lansing called the cabinet together for consultations on several occasions. In addition, he was the first cabinet member to suggest that Vice President Thomas R. Marshall assume the powers of the presidency. Displeased by Lansing's independence, Edith Wilson requested Lansing's resignation.[citation needed] Lansing stepped down from his post on February 12, 1920.[4][5]

After leaving office, Lansing resumed practicing law. He died in New York City on October 30, 1928, and was buried at Brookside Cemetery in Watertown, New York.

Personal life and family[]

In 1890, Lansing married Eleanor Foster, the daughter of Secretary of State John W. Foster.[6] Eleanor's older sister Edith was the mother of John Foster Dulles, who also became Secretary of State, Allen Welsh Dulles who served as Director of Central Intelligence, and Eleanor Lansing Dulles, an economist and high level policy analyst and advisor for the State Department.[7][8]

New York State Senator Robert Lansing (1799–1878) was his grandfather; Chancellor John Lansing Jr. and State Treasurer Abraham G. Lansing were his great-granduncles.

Authorship[]

Lansing was associate editor of the American Journal of International Law, and with Gary M. Jones was the author of Government: Its Origin, Growth, and Form in the United States (1902). He also wrote: The Big Four and Others at the Peace Conference, Boston (1921) and The Peace Negotiations: A Personal Narrative,[9] Boston/New York (1921).

Legacy and honors[]

During World War II the Liberty ship SS Robert Lansing was built in Panama City, Florida, and named in his honor.[10]

References[]

- ^ David Glaser (2015). Robert Lansing:A Study in Statecraft. pp. 1–3. ISBN 9781503545014.

- ^ Papers relating to the foreign relations of the United States, The Lansing Papers, 1914–1920, Volume I, Document 277. In the enclosure it is stated that "If the British Government is expecting an attitude of “benevolent neutrality” on our part—a position which is not neutral and which is not governed by the principles of neutrality—they should know that nothing is further from our intention."

- ^ PRECLÍK, Vratislav. Masaryk a legie (Masaryk and legions), váz. kniha, 219 str., vydalo nakladatelství Paris Karviná, Žižkova 2379 (734 01 Karvina, Czech Republic) ve spolupráci s Masarykovým demokratickým hnutím (Masaryk Democratic Movement, Prague), 2019, ISBN 978-80-87173-47-3

- ^ "The Chicago Daily News Almanac and Year Book for". 1920.

- ^ Williams, Joyce G. (1979). "The Resignation of Secretary of State Robert Lansing". Diplomatic History. 3 (3): 337–343. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.1979.tb00319.x. JSTOR 24910117.

- ^ Office of the Historian, U.S. Department of State, Biographies of the Secretaries of State: Robert Lansing accessed 13 January 2010

- ^ Internet Accuracy Project, John W. Foster accessed 13 January 2011

- ^ Office of the Historian, U.S. Department of State, Biographies of the Secretaries of State: John Watson Foster accessed 13 January 2011

- ^ Lansing, Robert (21 November 2018). "The peace negotiations, a personal narrative". Boston, New York, Houghton Mifflin company – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Williams, Greg H. (25 July 2014). The Liberty Ships of World War II: A Record of the 2,710 Vessels and Their Builders, Operators and Namesakes, with a History of the Jeremiah O'Brien. McFarland. ISBN 978-1476617541. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Robert Lansing". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Robert Lansing". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

Further reading[]

- Craft, Stephen G. "John Bassett Moore, Robert Lansing, and the Shandong Question." Pacific Historical Review 66.2 (1997): 231-249. Online

- Glaser, David. "1919: William Jenkins, Robert Lansing, and the Mexican Interlude." Southwestern Historical Quarterly 74.3 (1971): 337-356. Online

- Glaser, David. Robert Lansing: A Study in Statecraft(2015).

- Kahle, Louis G. "Robert Lansing and the Recognition of Venustiano Carranza." Hispanic American Historical Review 38.3 (1958): 353-372. Online

- Lazo, Dimitri D. "A Question of Loyalty: Robert Lansing and the Treaty of Versailles." Diplomatic History 9.1 (1985): 35-53. [ "A Question of Loyalty: Robert Lansing and the Treaty of Versailles." Online]

- Smith, Daniel M. Robert Lansing and American Neutrality, 1914-1917 (U of California Press, 1958).

- Smith, Daniel M. "Robert Lansing and the Formulation of American Neutrality Policies, 1914-1915." Mississippi Valley Historical Review 43.1 (1956): 59-81. Online

- Smith, Daniel M. "Robert Lansing." in An Uncertain Tradition: American Secretaries fif. State in the Twentieth Century (1961) pp: 61+.

Primary sources[]

- Grenville, John Ashley Soames. "The United States decision for war, 1917: Excerpts from the manuscript diary of Robert Lansing." Culture, Theory and Critique 4.1 (1960): 59-81.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Robert Lansing. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Robert Lansing |

- Robert Lansing Papers at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton University

- Works by Robert Lansing at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Robert Lansing at Internet Archive

- The Peace Negotiations: A Personal Narrative

- Robert Lansing (1921). The Peace Negotiations: a personal narrative at Project Gutenberg

- U.S. Diplomatic Security - Office of Foreign Missions (OFM)

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). 1922.

- 1864 births

- 1928 deaths

- United States Secretaries of State

- Woodrow Wilson administration cabinet members

- American legal writers

- American political writers

- American male non-fiction writers

- Amherst College alumni

- Lansing family

- Dulles family

- New York (state) Democrats

- New York (state) lawyers

- Politicians from Watertown, New York

- Writers from New York (state)

- 20th-century American politicians