Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise

| Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise | |

|---|---|

Japanese theatrical release poster | |

| Japanese | 王立宇宙軍~ オネアミスの翼 |

| Hepburn | Ōritsu Uchūgun: Oneamisu no Tsubasa |

| Directed by | Hiroyuki Yamaga |

| Written by | Hiroyuki Yamaga |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Hiroshi Isakawa |

| Edited by | Harutoshi Ogata |

| Music by |

|

Production company | Gainax |

| Distributed by | Toho Towa |

Release date |

|

Running time | 119 minutes |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

| Budget | ¥800 million[1] |

| Box office | ¥347 million[a] |

Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise (Japanese: 王立宇宙軍~オネアミスの翼, Hepburn: Ōritsu Uchūgun: Oneamisu no Tsubasa) is a 1987 Japanese animated science fiction film written and directed by Hiroyuki Yamaga, co-produced by Hiroaki Inoue and Hiroyuki Sueyoshi, and planned by Toshio Okada and Shigeru Watanabe. Ryuichi Sakamoto, later to share the Academy Award for the soundtrack to The Last Emperor, served as music director. The film's story takes place on an alternate world where a disengaged young man, Shirotsugh, inspired by an idealistic woman named Riquinni, volunteers to become the first astronaut, a decision that draws them into both public and personal conflict. The film was the debut work of anime studio Gainax, whose later television and movie series Neon Genesis Evangelion would achieve international recognition,[3] and was the first anime produced by toy and game manufacturer Bandai, eventually to become one of Japan's top anime video companies.[4]

Yamaga and Okada had become known through making amateur fan-oriented short films, particularly the Daicon III and IV Opening Animations, but their pitch for Royal Space Force argued that growing the anime industry required a shift away from works that pleased fans on a surface level but reinforced their isolation, advocating instead for a different type of anime that attempted to engage with fans as human beings who shared in the alienation issues of a larger society. The making of Royal Space Force involved a collaborative year-long design process using many creators, including some from outside the anime industry, to construct an elaborately detailed alternate world described as neither utopian nor dystopian, but "an attempt to approve existence".[5] Science fiction author Ted Chiang, whose work was the basis for the Academy Award-nominated film Arrival, would later describe Royal Space Force as the single most impressive example of world building in books or film.[6]

Royal Space Force's collective approach to filmmaking, its deliberate rejection of established anime motifs, its visual complexity, and the general lack of professional experience among its staff were all factors in its chaotic production, while increasing uncertainty about the project led to what has been described as an attempt by its investors and producers to "fix" the film before release, imposing a late name change to The Wings of Honnêamise, and a lavish but deceptive publicity campaign[7] that included misleading advertising as well as a staged premiere at Mann's Chinese Theatre on February 19, 1987. Although receiving a generally good reception among domestic anime fans and the industry upon its March 14, 1987 release in Japan, including praise from Hayao Miyazaki,[8] the film failed to make back its costs at the box office, but eventually became profitable through home video sales.[9]

Royal Space Force did not receive an English-language commercial release until 1994, when Bandai licensed the film to Manga Entertainment. A dubbed 35 mm version toured theaters in North America and the United Kingdom, during which time it received coverage in major newspapers but highly mixed reviews. Since the mid-1990s, it has received several English-language home video releases, and various historical surveys of anime have regarded the film more positively; the director has stated his belief in retrospect that the elements which made Royal Space Force unsuccessful made possible the later successes of Studio Gainax.[10][b]

Plot[]

In the Kingdom of Honnêamise— on a different, Earthlike world of mid-20th century technology— a young man named Shirotsugh Lhadatt recalls his middle-class upbringing and childhood dream to fly jets for the navy. His grades disqualifying him, Shirotsugh ended up instead joining the "Royal Space Force," a tiny unit with poor morale whose commander, General Khaidenn, dreams of human spaceflight, yet is barely capable of launching unmanned satellites. One night, Shirotsugh encounters a woman named Riquinni who is preaching in the red-light district. Riquinni Nonderaiko, who lives with a sullen little girl named Manna, surprises him by suggesting that humanity could find peace through space travel. Inspired, Shirotsugh volunteers for a last-ditch project to keep the Space Force from being disbanded: send the first astronaut into orbit.

Riquinni gives Shirotsugh scriptures to study, but becomes upset when he touches her and angry when he suggests she should "compromise" with God. Riquinni feels such compromise is to blame for the evils of the world, but Shirotsugh suggests it has made it easier to live in. The General arranges a shady deal to help finance his project, and tells a cheering crowd that the orbital capsule will be a "space warship". Soon after, Riquinni's cottage is foreclosed upon and demolished; not wishing to expose Manna— whose mother was constantly abused by her husband— to any more conflicts, she rejects the outraged Shirotsugh's offer to get her a lawyer. He begins to read Riquinni's scriptures, which assert that humanity is cursed to violence for having stolen fire.

A test explosion that kills the chief rocket engineer is suggested to be the work of radicals, and Shirotsugh confounds his friends by sympathizing with protestors who say the mission is a waste of federal funding. The launch site is suddenly moved to the Kingdom's southern border, which will assist in reaching orbit but is also adjacent to a territory occupied by their international rival, the distant Republic. The General learns to his shock that his superiors see the rocket only as a useful provocation; unknown to the Kingdom, the Republic plans to buy time to get their forces into position by assassinating Shirotsugh.

Increasingly disenchanted, Shirotsugh goes AWOL, giving his money to the homeless and joining Riquinni's ministry, but is troubled by Manna's continued silence and seeing the money Riquinni keeps. He turns away when she reads from her scriptures that one’s own efforts at truth and good will fail, and one can only pray. That night, he sexually assaults her; when he hesitates momentarily, she knocks him unconscious. Next morning, a repentant Shirotsugh is bewildered when Riquinni maintains he did nothing, apologizing for having hit “a wonderful person like you". Reuniting with his best friend Marty, Shirotsugh asks whether one might be the villain in one's own life's story, not its hero. Marty replies with the view that people exist because they serve purposes for one another. The Republic's assassin strikes— Shirotsugh attempts to flee, but eventually fights back, killing the assassin. The General confides in the wounded astronaut afterwards that he once wanted to be a historian and not a soldier, but found history harder to confront, because it taught him human nature would not change.

At the launch site, the crew finishes assembling the rocket even as both sides prepare for the expected attack. Without informing his superiors, the General decides to launch early by trimming safety procedures, to which Shirotsugh agrees. When the Republic's forces invade to seize the rocket by force, an evacuation is ordered, but Shirotsugh rallies the crew to proceed with the countdown. The combined ground-air assault ceases with the rocket's unexpected launch, and the Republic forces withdraw. From orbit, Shirotsugh makes a radio broadcast, uncertain if anyone is listening: although humans have brought ruin to each new frontier, he asks nevertheless to give thanks for this moment, praying for forgiveness and guidance. As the capsule crosses into the dayside, a montage of visions suggests Shirotsugh's childhood and the passage of history; far below, Riquinni, preaching where he first met her, is the only one to look up as the snow begins to fall, and the camera draws back, past the ship and its world, to the stars.

Cast[]

| Character | Japanese[12] | English[13] |

|---|---|---|

| Shirotsugh Lhadatt | Leo Morimoto | David A. Thomas |

| Riquinni Nonderaiko | Mitsuki Yayoi | Heidi Lenhart |

| Manna Nonderaiko | Aya Murata | Wendee Lee |

| Marty Tohn | Kazuyuki Sogabe | Bryan Cranston |

| General Khaidenn | Minoru Uchida | Steve Bulen |

| Dr. Gnomm | Chikao Ōtsuka | Michael Forest |

| Kharock | Masato Hirano | Tom Konkle |

| Yanalan | Bin Shimada | |

| Darigan | Hiroshi Izawa | Stephen Apostolina |

| Domorhot | Hirotaka Suzuoki | Jan Rabson |

| Tchallichammi | Kouji Totani | Christopher de Groot |

| Majaho | Masahiro Anzai | Tony Pope |

| Nekkerout | Yoshito Yasuhara | Dan Woren |

| Prof. Ronta | Ryūji Saikachi | Kevin Seymour |

Production[]

Development[]

Royal Space Force developed out of an anime proposal presented to Shigeru Watanabe of Bandai in September 1984 by Hiroyuki Yamaga and Toshio Okada[14] from Daicon Film, an amateur film studio active in the early 1980s associated with students at the Osaka University of Arts and science fiction fandom in the Kansai region.[15] The Daicon Film staff had met Watanabe earlier through their related fan merchandise company General Products, during his involvement with product planning for Bandai's "Real Hobby Series" figurines.[16] The position had also led Watanabe into Bandai's then-new home video label Emotion, where he helped to develop Mamoru Oshii's Dallos. Released at the end of 1983, Dallos would become the first anime original video animation (OVA),[17] an industry event later described as the beginning of a new "third medium" for anime beyond film or television, offering the prospect of "a medium in which [anime] could 'grow up,' allowing the more mature thematic experiments of creators".[18]

Okada and Yamaga's pitch to Watanabe had followed the recognition Daicon Film received earlier that year in Animage magazine through a special secondary Anime Grand Prix award given to their 8 mm short Daicon IV Opening Animation.[c] Their September 1984 proposal gave the outline for an anime to be entitled Royal Space Force, to be produced under the heading of a new, professional studio to be named Gainax.[20] The proposal listed five initial core staff for the anime.[21] Four had been previously associated with Daicon Film: Yamaga was to be the anime's concept creator and director and Okada its producer,[d] Yoshiyuki Sadamoto its chief character designer, and Hideaki Anno its chief mechanical designer. The fifth, Kenichi Sonoda, listed as responsible for the anime's settei (model sheets, drawn up to give the key animators their guides as to how the objects and people to be animated should look) had previously assisted with product development at General Products.[16][e]

Writing[]

The Royal Space Force proposal, subheaded "Project Intentions: A New Wave in a Time of Lost Collaborative Illusions,"[27] began with a self-analysis of "recent animation culture from the perspective of young people".[28][f] At the time of the proposal, Yamaga was 22 years old and had directed the opening anime films for Japan's 1981 and 1983 national science fiction conventions, Daicon III and IV,[30] which through their sale to fans on home video through General Products were themselves regarded as informal precursors of the OVA concept.[31] At age 20 and while still in college, Yamaga had been chosen by the series director of the original Macross TV series, Noboru Ishiguro, to direct episode 9 of the show, "Miss Macross," as Ishiguro wished "to aim for a work that doesn’t fit the conventional sense of anime." Yamaga commented in a contemporary Animage article that it had taken him two months to create the storyboards for "Miss Macross" and wryly remarked he'd thus already used himself up doing so; the magazine noted however that the episode was well received, and judged the creative experiment a success.[32][g]

Okada and Yamaga argued in their proposal for Royal Space Force that what prevented the anime industry from advancing beyond its current level was that it had fallen into a feedback loop with its audience, producing for them a "cul-de-sac" of cute and cool-looking anime content that had the effect of only further reinforcing the more negative and introverted tendencies of many fans,[34][h] without making a real attempt to connect with them in a more fundamental and personal way:

"In modern society, which is so information-oriented, it becomes more and more difficult even for sensational works to really connect with people, and even so, those works get forgotten quickly. Moreover, this flood of superficial information has dissolved those values and dreams people could stand upon, especially among the young, who are left frustrated and anxious. It could be said that this is the root cause of the Peter Pan syndrome, that says, 'I don't want to be an adult' ... If you look at the psychology of anime fans today, they do interact with society, and they're trying to get along well in that society, but unfortunately, they don't have the ability. So as compensatory behavior, they relinquish themselves to mecha and cute young girls. However, because these are things that don't really exist—meaning, there's no interaction in reality happening between those things and the anime fans—they soon get frustrated, and then seek out the next [anime] that will stimulate them ... If you look into this situation, what these people really want, deep down, is to get along well with reality. And what we propose is to deliver the kind of project that will make people look again at the society around them and reassess it for themselves; where they will think, 'I shouldn't give up yet on reality.'"[37][i]

The proposal described Royal Space Force as "a project to make anime fans reaffirm reality".[39] Gainax asserted that the problem was not unique to anime fans, who were only "the most representative example" of the increasing tendency of younger people not to experience reality directly, but as mediated through "the informational world".[40] "We live in a society mired in a perpetual state of information overload. And the feeling of being overwhelmed by the underwhelming isn't something limited to just young people, but everyone" ... "However, this doesn't mean that people want to live alone and without contact, but instead they want to establish a balance with the 'outside' that is psychologically comfortable for them."[41] Yamaga and Okada believed that this sensibility among some fans explained why anime often combined plots that "symbolize modern politics or society" with characters whose age and appearance was "completely incongruent with reality".[42][j] The Royal Space Force plan proposed to use the creative techniques of anime for a radically different aim, to make "the exact opposite of the 'cool,' castle-in-the-sky anime[k] that is so prevalent these days ... It's on our earth now, in this world of ours now, that we feel it's time for a project that will declare there's still something valuable and meaningful in this world."[49]

"It is essential to pay close attention to the smallest design details of this world. It's because it is a completely different world that it must feel like reality. If you ask why such an approach—when the goal is to get anime fans to reaffirm their reality—it's because if you were to set this anime in our actual world to begin with, that's a place which right now they see as grubby and unappealing. By setting it in a completely different world, it becomes like a foreign film that attracts the attention of the audience. The objects of attraction are not mecha and cute girls, but ordinary customs and fashions. If normal things now look impressive and interesting because they've been seen through a different world, then we'll have achieved what we set out to do in the plan; we'll be able to express, 'Reality is much more interesting than you thought.'"[50]

The September 1984 proposal for Royal Space Force was unusual for an anime pitch in that it described the setting and story, but never named the main characters.[51] The written proposal was accompanied by a set of over 30 "image sketches" depicting the world to be designed for the anime, painted in watercolor by Sadamoto and Mahiro Maeda.[14] Maeda, a high school classmate of Daicon Film director and character designer Takami Akai, had attended Tokyo Zokei University with Sadamoto; Maeda and Sadamoto had also worked on the Macross TV series, and both were subsequently recruited into Daicon Film.[52] That same month, Watanabe brought the pitch to Bandai company president Makoto Yamashina, who himself represented a younger corporate generation;[53] Yamashina's response to reading Gainax's proposal was, "I'm not sure what this is all about, but that's exactly why I like it."[54] Yamashina would later state in an interview with the comics and animation criticism magazine Comic Box shortly before the film's release that this viewpoint represented a "grand experiment" by Bandai in producing original content over which they could have complete ownership, and a deliberate strategy that decided to give young artists freedom in creating that content: "I'm in the toy business, and I've always been of the mind that if I understand [the appeal of a product], it won't sell. The reason is the generation gap, which is profound. Honneamise just might hit the jackpot. If so, it will overturn all the assumptions we’ve had up till now. I didn't want them to make the kind of film that we could understand. Put another way, if it was a hit and I could understand why, it wouldn't be such a big deal. I did want it to be a hit, but from the start, I wasn't aiming for a Star Wars. In trying to make it a success, it had to be purely young people's ideas and concepts; we couldn't force them to compromise. We had to let them run free with it. In the big picture, they couldn't produce this on their own, and that's where we stepped in, and managed to bring it all this way. And in that respect, I believe it was a success."[55]

Pilot film[]

"This was a project that made full use of all sorts of wiles. At the time, Hayao Miyazaki said, 'Bandai was fooled by Okada's proposal.' I was the first person at Bandai to be fooled (laughs). But no, that's not the case. I'm a simple person; I just wanted to try it because it looked interesting. Nobody thought that Bandai could make an original movie. There wasn't any know-how at all. But that's why I found it interesting. No, to be honest, there were moments when I thought, 'I can't do this.' But [Gainax]'s president, Okada, and the director, Yamaga, both thought strongly, 'I want to make anime professionally, and speak to the world.' Producer Hiroaki Inoue felt the same way, as did [Yasuhiro] Takeda ... I was about the same age, so I got into the flow of all those people's enthusiasm." —Shigeru Watanabe, 2004[56][l]

Royal Space Force was initially planned as a 40-minute long OVA project,[57] with a budget variously reported at 20[58] or 40[59] million yen; however, resistance elsewhere within Bandai to entering the filmmaking business resulted in the requirement that Gainax first submit a short "pilot film" version of Royal Space Force as a demo to determine if the project would be saleable.[60] Work on the pilot film began in December 1984[14] as Yamaga and Okada moved from Osaka to Tokyo to set up Gainax's first studio in a rented space in the Takadanobaba neighborhood of Shinjuku.[61] That same month, Gainax was officially registered as a corporation in Sakai City, Osaka; founding Gainax board member Yasuhiro Takeda has remarked that the original plan was to disband Gainax as soon as Royal Space Force was completed; it was intended at first only as a temporary corporate entity needed to hold production funds from Bandai during the making of the anime.[62]

The Royal Space Force pilot film was made by the same principal staff of Yamaga, Okada, Sadamoto, Anno, and Sonoda listed in the initial proposal, with the addition of Maeda as main personnel on layouts and settei; Sadamoto, Maeda, and Anno served as well among a crew of ten key animators that included Hiroyuki Kitakubo, Yuji Moriyama, Fumio Iida, and Masayuki.[63] A further addition to the staff was co-producer Hiroaki Inoue, recruited as a founding member of Gainax by Okada. Inoue was active in the same Kansai-area science fiction fandom associated with Daicon Film, but had already been in the anime industry for several years, beginning at Tezuka Productions.[64] Takeda noted that while a number of the other Royal Space Force personnel had worked on professional anime projects, none possessed Inoue's supervisory experience, or the contacts he had built in the process.[59] Inoue would leave Gainax after their 1988–1989 Gunbuster, but continued in the industry and would later co-produce Satoshi Kon's 1997 debut film Perfect Blue.[65]

In a 2004 interview, Shigeru Watanabe, by then a senior managing director and former president of Bandai Visual, who in later years had co-produced such films as Mamoru Oshii's Ghost in the Shell and Hiroyuki Okiura's Jin-Roh,[66] reflected on his personal maneuvers to get Royal Space Force green-lit by Bandai's executive board, showing the pilot film to various people both inside and outside the company, including soliciting the views of Oshii[m] and Miyazaki.[68] As Bandai was already in the home video business, Watanabe reasoned that the strong video sales of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, released the previous year, meant that Miyazaki's opinions would hold weight with Bandai's executives.[69] Watanabe visited Miyazaki's then-studio Nibariki alone and spoke with the director for three hours, of which time, Watanabe joked, he got to speak for ten minutes. Miyazaki, who had worked with Hideaki Anno on Nausicaä,[70] told him, "Anno and his friends are amateurs, but I think they're a little different," comparing the matter to amateurs having "a gorgeous bay window" versus having a foundation: "They feel like they can make the foundation, and maybe raise a new building. If necessary, you can give that advice to the Bandai board." Watanabe laughed that when he told the executives what Miyazaki had said, they approved the project.[71]

In April 1985, Okada and Yamaga formally presented the finished pilot film to a board meeting at Bandai, together with a new set of concept paintings by Sadamoto. The four-minute pilot film began with a 40-second prelude sequence of still shots of Shirotsugh's early life accompanied by audio in Russian depicting a troubled Soviet space mission, followed by a shot of a rocket booster stage separating animated by Anno,[72] leading into the main portion of the pilot, which depicts the story's basic narrative through a progression of animated scenes without dialogue or sound effects, set to the overture of Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg.[73] Okada addressed the board with a speech described as impassioned,[74] speaking for an hour on Gainax's analysis of the anime industry, future market trends, and the desire of the young for "a work called Royal Space Force".[75] Bandai gave interim approval to Royal Space Force as their company's first independent video production; however, the decision to make the project as a theatrical film would be subject to review at the end of 1985, once Gainax had produced a complete storyboard and settei.[76]

In a 2005 column for the online magazine Anime Style, editor and scriptwriter Yuichiro Oguro recalled seeing a video copy of the pilot film secretly circulating after its completion around the anime industry, where there was interest based on Sadamoto and Maeda's reputations as "the genius boys of Tokyo Zokei University".[77] Oguro noted as differences from the later finished movie the pilot film's younger appearance of Shirotsugh and more bishōjo style of Riquinni, whose behavior in the pilot put him in mind of a Miyazaki heroine, as did the composition of the film itself.[78]

Yamaga, in a 2007 interview for the Blu-ray/DVD edition release, confirmed this impression about the pilot film and speculated on its consequences:

"It's clearly different from the complete version, and by using the modern saying, it's very Ghiblish ... Among the ambitious animators of those days, there was some sort of consensus that 'if we can create an animated movie that adults can watch, with decent content "for children" which director Hayao Miyazaki has, it will be a hit for sure.' The pilot version was also created under that consensus unconsciously. However, I figured it's not good to do so, and my movie making started from completely denying that consensus. Of course, if we had created this movie with the concept of the world similar to the pilot version, it would've had a balanced and stable style, and not only for staff, but also for sponsors, motion picture companies, and the media ... it would have been easier to grasp and express. But if we had done that, I don't think that any of the Gainax works after that would've been successful at all."[10]

Screenplay[]

"The film was Gainax's call to the world, of how we would be. The story of the anime is explaining why we are making anime in the first place. The lift-off of the rocket was only a preview of our future, when we were saying to ourselves, 'Oh, we will do something!' But those feelings are mostly gone, just like memories, just like the person you were when you were young. It has almost gone away. But there is still the real thing, the film we made, that tells our story."—Toshio Okada, 1995[79]

Following the presentation of the pilot film, Yamaga returned to his hometown of Niigata to begin to write the screenplay and draw up storyboards, using a coffeehouse in which to work, taking glances out the window.[80] The opening scene of Royal Space Force, narrated by an older Shirotsugh considering his past, depicts a younger Shiro witnessing the takeoff of a jet from an aircraft carrier; the look of the scene is directly inspired by the winter damp and gloom of Niigata's coastline along the Sea of Japan.[81] Yamaga envisioned the fictional Honnêamise kingdom where most of the events of Royal Space Force took place to have the scientific level of the 1950s combined with the atmosphere of America and Europe in the 1930s, but with characters who moved to a modern rhythm. The inspiration he sought to express in anime from Niigata was not the literal look of the city, but rather a sense of the size and feel of the city and its envrions, including its urban geography; the relationships between its old and new parts, and between its denser core and more open spaces.[82]

In August 1985, six members of the Royal Space Force crew, Yamaga, Okada, Inoue, Sadamoto, and Anno from Gainax, accompanied by Shigeru Watanabe from Bandai, traveled to the United States for a research trip, studying postmodern architecture in New York City, aerospace history at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.,[83] and witnessing a launch of the Space Shuttle Discovery at Kennedy Space Center in Florida.[84] Documentary footage of the research trip was shot by Watanabe[85] and incorporated into a promotional film released two weeks before the Japanese premiere of Royal Space Force.[86] Yamaga made revisions to the script during the American research tour.[87] While staying in the US, the group was surprised and amused to see an English-dubbed version of Macross showing on their hotel room TV, a series which Yamaga, Anno, and Sadamoto had all worked upon; the scenes were from a rerun of Robotech, which had completed its initial run on American television earlier that summer.[88][89]

Noriaki Ikeda, winner of the 1986 Seiun Award for nonfiction, began a series of articles on the film's production that year for Animage. After watching a rough edit of the film, Ikeda wrote that Royal Space Force was an anime that reminded him of what the works of the American New Wave had brought to the live-action movies of Hollywood in the 1960s; perceiving in the film an effort by Gainax to create a work with their own sense of words and rhythm, employing natural body language, raw expressions, and timing, and an overall "texture" that made a closer approach to human realities.[92] Reviewing the completed film five months later, Ikeda made extensive comment on the scriptwriting: "It's been some time since I've seen an original work that pays so much attention to dialogue, and features such subtle nuance," contrasting it to "the anime we're used to seeing these days, that scream their message at you." Ikeda remarked in particular on how supporting characters were given dialogue to speak that was independent of the main storyline, which gave a sense that they were real human beings, and how this was further expressed in scenes that managed to convey "dialogue without dialogue," such as the sequence in the rocket factory where characters are seen to converse although only music is heard on the audio track.[93]

In a roundtable discussion with the anime magazine OUT following the film's theatrical release, Yamaga remarked, "I wanted to taste the sense of liberation I could get if I recognized everything [about human nature] and included it," a view with which Okada had concurred, saying, "this is a film that acknowledges people in their every aspect".[94] On the 2000 DVD commentary, Yamaga stated of the character relationships in Royal Space Force that "A critic once said that none of the characters in this film understand each other. That there's no communication between the characters. He was exactly right. The characters don't understand each other at all. But throughout the film, there are moments where there are glimpses of understandings between [Shirotsugh] and the other characters ... In reality, it's okay not to understand each other. People all live their individual lives—it's not necessary to feel the same way another feels. And in fact you will never understand anybody anyway. This is how I feel about the relationships I have with the people in my life."[95][n]

Three years after his 1992 departure from Gainax,[97] Okada reflected on the film's screenplay in an interview with Animerica: "Our goal at first was to make a very 'realistic' film. So we couldn’t have the kind of strong, dramatic construction you’d find in a Hollywood movie. [Royal Space Force] is an art film. And at the time, I thought that was very good, that this is something—an anime art film. But now when I look back, I realize ... this was a major motion picture. Bandai spent a lot of money on it. It was our big chance. Maybe if I’d given it a little stronger structure, and a little simpler story—change it a little, make it not so different—it could have met the mainstream."[98] "I think the audience gets confused at three points in the film: the first scene, which is Shiro’s opening monologue, the rape scene, and the prayer from space. Why? The film needed a stronger structure. A little more. A few changes, and the audience would be able to follow Shiro's thoughts. But right now, they miss it, and that’s a weakness. It’s true that there will be ten or twenty percent of the audience who can follow it as is, and say, 'Oh, it's a great film! I can understand everything! ' But eighty percent of the audience is thinking, 'I lost Shiro’s thoughts two or three times, or maybe four or five.' Those are the kind of people who will say, 'The art is great, and the animation is very good, but the story—mmmm...'"[99] Okada remarked however that the decentralized decision-making creative process at Gainax meant there were limits to how much control could be asserted through the script;[48] Akai would later comment that "the staff were young and curious, not unlike the characters in the film. If you tried to control them too much, they would have just walked out."[100]

Yamaga asserted that a "discrepancy between who [Riquinni] wanted to be and who she really was...is evident in her lifestyle and dialogue,"[101] and that "on the outside," she carries an image of Shiro as "'an extraordinary being who travels through space into this peaceful and heavenly place'... But deep down inside she knows the truth. She's not stupid."[102] The director remarked that Riquinni's actions and dialogue in the film's controversial scenes of assault and the morning after reflect the dissonances present in both her self-image and her image of Shiro, and that the scene "was very difficult to explain to the staff" as well; that she is signaling her strength to go on living according to her beliefs, and without Shiro in her life any longer.[103] "There's no simple explanation for that scene, but basically, I was depicting a human situation where two people are moving closer and closer, yet their relationship isn't progressing at all...[Shiro resorts] to violence in an attempt to close that gap, only to find that was also useless. The two of them never came to terms, never understood each other, even to the end of the movie. However, even though they never understood each other, they are in some way linked together..." Yamaga affirmed that the scene where Riquinni looks up from her farm labor at the jet overhead was meant to be a match with the young Shiro doing the same in the opening monologue, yet at the same time showing that she and Shiro lived their lives in different worlds. "Whereas [in the final scene] with the snow, it's actually touching her, so there is a small intimacy in that image. But the snow is very light—it melts the moment it falls. So then, are they touching, or aren't they touching? I wanted to depict an ambiguous relationship between them at the very end."[104] "When there's a man and a woman in a film, you automatically think that there's going to be a romance between them, but I didn't mean for it to be that way. Looking back now, I realize that it's difficult to comprehend a story about a man and a woman without romance, but at the time I made this film, I felt that a relationship between a man and a woman did not have to be a romantic one."[105]

Design[]

In May 1985, Gainax transferred their operations to another location in Takadanobaba that offered twice the space of their previous studio, where the existing staff gathered in friends and acquaintances to help visualize the setting of Royal Space Force.[106] Among those joining the crew at this time were two of the film's most prolific world designers: Takashi Watabe, whose designs would include the train station, rocket factory, and Royal Space Force lecture hall[107] and Yoichi Takizawa, whose contributions included the rocket launch gantry, space capsule simulator, and rocket engine test facility.[108]

Yamaga decided that the vision of the alternate world depicted in the pilot film did not have the kind of different realism he was hoping to achieve in the completed work. Rather than use the design work of the pilot as a foundation for the full-length anime, it was decided to "destroy" the world of the pilot film and start over again, creating a new series of "image board" paintings to visualize the look of Royal Space Force. The total worldbuilding process went on for roughly a year, and was described as a converse process between Yamaga and the gradually assembled team of designers; expressing his ideas into concrete terms, but also bringing their concrete skills to bear toward the expression of abstract ideas.[109] Yamaga reflected in 2007 that this reciprocal process influenced his writing on the film: "My style is not 'I have a story I created, so you help me make it.' Creators come first, and this is a story I created thinking what story those creators would shine at the most."[110]

In the decade following Royal Space Force, the Sadamoto-designed Nadia La Arwall[111][112] and Rei Ayanami[113][114] would each twice win the Anime Grand Prix fan poll for favorite female character; Sadamoto's Shinji Ikari[115][116] would also win twice for favorite male character. By contrast, his male and female leads designed for Royal Space Force, Shirotsugh and Riquinni, ranked ninth and twentieth respectively for their categories in the Grand Prix poll of 1987 releases.[117] In a roundtable discussion on Royal Space Force following its release, it was pointed out that neither Shirotsugh nor Riquinni look like typical anime lead characters.[118] Yamaga remarked in his 2007 retrospective that, "One of the changes you can easily see from the pilot version is the character modeling of the protagonist. He used to look like a boy, but has become like a middle-aged man. As you can see in Evangelion later on, characters that Yoshiyuki Sadamoto creates are more attractive when they look young. But of course, he's really skilled, so even if he challenges the area that's not his specialty, he can give us what we're asking for."[110]

Sadamoto in fact did use for the final version of Shirotsugh a model reference significantly older than the 21-year old character's age,[119] the American actor Treat Williams, although the character designer remarked that that Yamaga's instructions to make the face square and the eyebrows thicker had him thinking the redesign would look like the director himself.[120] As a reference for Manna, Yamaga referred Sadamoto to actress Tatum O'Neal as she appeared in the first half of the film Paper Moon.[121] Takami Akai remarked that "Sadamoto drew Manna so perfectly that we were sort of intimidated," adding she was "a sidekick who brought out the darker aspects" of Riquinni.[122] Regarding Riquinni herself, Sadamoto commented in 1987 that there seemed to be a model for her, but Yamaga did not tell him who it was.[123] In a 2019 interview session with Niigata University, Yamaga remarked, "What I see now is surprisingly the character Riquinni is nothing but me. At any rate, Shirotsugh is not me. If you ask me where I would position myself in the film, I would identify myself as Riquinni in many aspects, in terms of the way I think. I was probably someone weird [and] religious, ever since my childhood."[124][o] The appearance of several minor characters in Royal Space Force was based on Gainax staff members or crew on the film, including Nekkerout (Takeshi Sawamura),[64] the Republic aide who plans Shirotsugh's assassination (Fumio Iida),[127] and the director who suggests what Shiro should say before he walks out of his TV interview (Hiroyuki Kitakubo).[128]

Commenting on the character designs in Royal Space Force, Sadamoto remarked that in truth they more reflected the tastes of Gainax than his own personal ones, although at the same time, as the artist, his taste must be reflected in them somehow.[129] Sadamoto discussed the issue in terms of anime character design versus manga character design: "Manga can afford such strong and weird characters, but it's difficult to make good moving characters out of them in anime. The moment I draw a character, for example, you can see how it is going to behave, really ... but I was asking myself what I should be doing. 'Should I make their facial expressions more like those you see in a typical anime?' and so on. I feel that the audience reaction was pretty good, or at least that I managed to get a passing grade."[130]

On the premise that the real world itself was a product of mixed design, Yamaga believed that the sense of alternate reality in Royal Space Force would be strengthened by inviting as many designers as possible to participate in the anime.[131] By September, the worldbuilding of Royal Space Force proceeded forward by a system where designers were free to draw and submit visual concepts based on their interpretation of Yamaga's script; the concept art would then be discussed at a daily liaison meeting between Yamaga and the other staff.[132] Yamaga compared the approach to abstraction in painting, seeking to liberate the audience from their prior view of real life by subtly changing the shape of familiar things; citing as an example the image of "a cup," and trying to avoid the direct impulse to draw a cylindrical shape.[133]

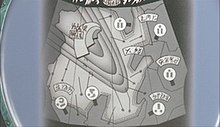

Assistant director Shinji Higuchi had overall responsibility for coordinating the design work with Yamaga's intentions through overseeing the output of its multiple designers; Higuchi noted moreover that the film's main mecha were designed in a collaborative fashion, citing as an example the Honnêamise air force plane, for which Sadamoto first created a rough sketch, then Takizawa finished up its shape, with its final touches added by Anno.[134] Although his aim was to give a unified look to the kingdom of Honnêamise as the film's main setting, Higuchi also attempted to take care to make it neither too integrated nor too disjointed, remarking that just as the present day world is made from a mixing of different cultures, this would have also been true of a past environment such as the alternate 1950s world of Honnêamise.[135] Yamaga commented that the film also portrayed the idea that different levels of technology are present in a world at the same time depending upon particular paths of development, such as the color TV in use by the Republic, or the air combat between jet and prop planes at the end, which Yamaga compared to similar engagements during the Korean War.[136]

A deliberate exception to Royal Space Force's general design approach was the rocket itself, which was adapted from a real-world Soviet model.[137][p] This exception was later noticed by Hayao Miyazaki, for whom it formed one of his two criticisms of the anime; he was surprised that a film which had gone so far as to change the shape of money did not make the rocket more unusual.[139] Yamaga argued that although the anime reaches its eventual conclusion through a process of different design paths, it was necessary to end the film with a rocket inspired by reality, lest the audience see it as a story about a different world that has nothing to do with them.[140] In their roundtable discussion with OUT, Gainax described the rocket as also emblematic of the film's approach to mecha; despite its many mecha designs, they all play supporting roles, and even the rocket is not treated as a "lead character".[141]

Art direction[]

Although later noted for creating much of the aesthetic behind the influential 1995 film Ghost in the Shell,[142] Hiromasa Ogura in a 2012 interview named his first project as an art director, Royal Space Force, as the top work of his career.[143] Ogura had entered the anime industry in 1977 as a background painter at Kobayashi Production, where he contributed art to such films as Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro and Harmagedon. At the time work began on Royal Space Force, Ogura was at Studio Fuga, a backgrounds company he had co-founded in 1983; he related that it was his associate Yoshimi Asari of Triangle Staff who contacted him on behalf of Gainax, arranging for Okada and Inoue to come to Fuga and discuss their plans for the film. Ogura mentioned that although he did not know the details of how Asari came to suggest him for the job, he found out later that Gainax had previously approached his seniors Shichirō Kobayashi and Mukuo Takamura, who had been the art directors on Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro and Harmagedon respectively,[144] but that both had passed on Royal Space Force.[145]

After joining the Royal Space Force team on temporary loan from Studio Fuga, Ogura worked in the film's pre-production studio in Takadanobaba. He later joked that his initial reaction to Gainax was "What's up with these people?", remarking that they acted like a bunch of students who all knew each other, whereas he had no idea who any of them were. Although Ogura recalled that he had seen the Daicon opening animation films before starting Fuga and had been impressed that amateurs had made them, he did not realize at first that he was now working with the same people, laughing that he likewise eventually recognized Anno from having seen his role in the live-action Daicon short The Return of Ultraman.[146][147] After the completion of Royal Space Force, Ogura went to work on his first collaboration with Mamoru Oshii, Twilight Q: Mystery Case File 538, but would later collaborate with Gainax again as art director of the final episodes of the 1990-91 TV series Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water[148] and of the 2000-01 OVA series FLCL, which Ogura personally ranked alongside his work on the Patlabor films and Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade, praising the unique world sense of FLCL series director Kazuya Tsurumaki and animator, designer, and layout artist Hiroyuki Imaishi.[149]

Ogura oversaw a team of 16 background painters on Royal Space Force,[86] including the future art director of Princess Mononoke, Spirited Away, and The Wind Rises, Yōji Takeshige. At the time of Royal Space Force's production, Takeshige was still a student attending Tama Art University; the following year he would join Studio Ghibli to create backgrounds for 1988's My Neighbor Totoro.[150] Ogura remarked that many of his team were veterans of Sanrio's theatrical films unit, which gave him confidence in their abilities; mentioning that one former Sanrio artist, future Gankutsuou art director Hiroshi Sasaki,[151] created the images for Royal Space Force's final sequence.[152][q] More than half of the background paintings for the film were made on site at Gainax, rather than assigning the task to staff working externally, as Ogura felt the worldview and details of the film's aesthetic were easier for him to communicate to artists in person, giving as an example the color subtleties; as the color scheme in Royal Space Force was subdued, if a painting needed more of a bluish cast to it, he couldn't simply instruct the artist to "add more blue."[154]

Toshio Okada described the appearance of the world in which Royal Space Force takes place as having been shaped in stages by three main artists: first, its major color elements (blue and brown) were determined by Sadamoto; then its architectural styles and artistic outlook were designed by [Takashi] Watabe, and finally Ogura gave it "a sense of life" through depicting its light, shadow, and air. It was noted also that the film's world displays different layers of time in its designs; the main motifs being Art Deco, but with older Art Nouveau and newer postmodern elements also present.[157] Yamaga expressed the view that Ogura being a Tokyo native allowed him to do a good job on the film's city scenes,[158] yet Ogura himself described the task as difficult; while he attempted to sketch out as much of the city as possible, its urban aesthetic was so cluttered that it was difficult for him to determine vanishing point and perspective.[159] Ogura commented that although the film depicted a different world, "there's nothing that you'd call sci-fi stuff, it's everyday, normal life like our own surroundings. I wanted to express that messy impression." As art director, he also laid particular emphasis on attempting to convey the visual texture of the world's architecture and interior design, remarking that he was amazed at how Watabe's original drawings of buildings contained detailed notes on the structural and decorative materials used in them, inspiring Ogura to then express in his paintings such aspects as the woodwork motifs prominent in the Royal Space Force headquarters, or by contrast the metallic elements in the room where the Republic minister Nereddon tastes wine.[160] Watabe and Ogura would collaborate again in 1995 on constructing the cityscapes of Ghost in the Shell.[161]

Ogura theorized that the background paintings in Royal Space Force were a result not only of the effort put into the film, but the philosophy behind the effort: "I think this shows what you can make if you take animation seriously. [Yamaga] often said he wanted to dispense with the usual symbolic bits. It isn't about saying that because it's evening, the colors should be signified in this way. Not every sunset is the same."[162] Critiquing his own work, Ogura wished that he had been able to convey more emphasis on the effects of light and shadow in addition to color, citing as an example the early scene at the graveyard, where he felt he should have depicted greater contrast in the objects lit by sunlight, but joked that it was hard to say exactly how things would turn out until he actually painted them, something he said was true of the entire film. As Yamaga conveyed images to him only through words, Ogura was glad that he was allowed to be free to try to express them visually in his own way,[163] particularly because even in evening shots, the director would specify to him whether it should depict evening close to dawn, the dead of night, or evening close to sunset, noting wryly that it was hard to express the difference between 3 a.m and 4 a.m.[164] Looking back on the project from 2012, Ogura maintained that while he rarely rewatched his old work, he still felt the passion when he viewed a DVD of the film: "I thought there aren't a lot of people these days making [anime] with such a level of passion. Royal Space Force was very exciting, and so were the people around me."[165]

In the 2000 director's commentary, Akai recalled his initial surprise that Yamaga wanted to use Nobuyuki Ohnishi's illustrations for the film's credits sequences, and that also "some of the animators felt there were better illustrators," a remark that made Yamaga laugh and comment, "The world of animators is a small one."[166] At the time of Royal Space Force's production, Ohnishi was known for his spot illustrations in the reader's corner section of Pia,[167] a weekly Tokyo culture and entertainment magazine associated with the long-running Pia Film Festival, as well as his airplane illustrations drawn for the magazine Model Graphix,[168] where an occasional fellow contributing artist was Hayao Miyazaki.[169] In a 1995 conversation with Animerica, Ohnishi remarked however that Yamaga's personal familiarity with his work came through Ohnishi's illustrations for the Japanese magazines Swing Journal, a jazz publication modeled on DownBeat,[170] and ADLIB, covering fusion and pop. He remembered having been "a little surprised" when Yamaga first approached him, as Ohnishi had "considered animation at the time to be strictly for children, and his own work had always been directed towards adults," but that Yamaga assured him that the film "was going to be a very adult take on science fiction."[171]

Yamaga had desired that the opening and ending credits show the world portrayed in the film from a different perspective, and felt that Ohnishi's method of using light and shadow was ideal for the purpose. He asked the artist to create an "image of inheritance,"[172] to convey a sense that this world did not exist only for the events told of in the film, but that it had existed also in its past, and would exist into its future as well.[173] Although his illustration style used a sumi-e ink wash painting technique from classical East Asian art, Ohnishi commented that he was uninterested in traditional subjects such as "bamboo and old Chinese mountains," preferring instead to paint "the typewriter and the skyscraper," with a particular interest in 1950s-era objects. Ohnishi's approach in the credits made frequent use of photographs of real people and historical events, which he would then modify when adapting it into a painting: "exchanging and replacing the details of, for example, a European picture with Asian or Middle-Eastern elements and motifs. In this way, the credits would reflect both the cultural mixing that gives the film as a whole its appearance, and symbolize the blurring between our world and the film's world, thus serving [Royal Space Force's] function as a 'kaleidoscopic mirror.'"[171] The last painting in the opening credits, where Yamaga's name as director appears, is based on a photograph of Yamaga and his younger sister when they were children.[174][171] Shiro's return alive from space[175] is depicted in the first paintings of the ending credits; Yamaga remarked that they represent the photos appearing in textbooks from the future of the world of Royal Space Force.[176]

Animation[]

After the completion in December 1985 of Daicon Film's final project, Orochi Strikes Again, its director Takami Akai and special effects director Shinji Higuchi moved to Tokyo to join the production of Royal Space Force as two of its three assistant directors, alongside Shoichi Masuo.[177] Higuchi would make the first scene actually animated and filmed in Royal Space Force, depicting a newsreel of Shirotsugh arriving in the capital city; its look was achieved by filming the cels using the same 8mm camera that Daicon had used for its amateur productions.[178] At age 20, Higuchi was the very youngest of the main crew;[179] his previous creative experience had been in live-action special effects films rather than anime. Higuchi was described as someone who did not "think like an animator," and would therefore bring unorthodox and interesting ideas and techniques to the project. The director felt that Royal Space Force benefitted from the creative contributions of people from outside anime, including opening and ending credits artist Nobuyuki Ohnishi, and several part-time college design students who did not go on to pursue a career in animation; Akai and Yamaga joked in retrospect that, owing to their scant experience, at the time they themselves had limited familiarity with the anime industry.[180]

The newsreel scene was located near the beginning of the storyboard's "C part".[r] The third out of the anime's four roughly equal half-hour divisions, the C part began with the scene of Riquinni working in the field, and concluded with the assassination attempt.[182] Royal Space Force followed the practice, adapted from TV episodes, of breaking the storyboard up into lettered parts; although intended to denote the parts before and after a mid-show commercial break, the practice was also used in theatrical works for convenience in production.[183] As 1985 drew to a close, Bandai had still not formally committed to Royal Space Force as a feature-length film release, as a distributor for the movie had not yet been secured.[184] Gainax was also late in finalizing the storyboard, which would not be completed in its entirety until June 1986.[185] However, the C part was nearly finished, and the decision was made to start production there, on the reasoning also that the sober tone of many C part scenes required precision in expression; as there was no release date yet, it was better to work on them while the schedule was still relatively loose.[186]

Royal Space Force assistant director Shoichi Masuo was an associate of Hideaki Anno, whom he had met when the two worked together on the 1984 Macross film. Anno had moved to Tokyo the previous year[70] to pursue a career as an independent animator; Masuo and Anno, who were the same age[187] were among the co-founders of Studio Graviton, a Tokyo office for animators working freelance such as themselves.[188] Masuo described the roles of himself and the two other assistant directors: Higuchi had overall charge regarding the design aspects of the settei, Masuo was in charge over the color aspects of the settei, including backgrounds,[s] whereas Akai monitored the work as a whole as general assistant to Yamaga. These roles were not fixed, and the three did not confer on a daily basis, but rather would have meetings on how to shift their approach whenever changes in the production situation called for it. Masuo noted as well that he had the most experience of the three in animation, and if an animator seemed confused over abstract directives from Yamaga, Masuo would explain in concrete terms how to execute the director's intent.[190] Regarding the animation style of Royal Space Force, Masuo remarked that it was generally straightforward, without the characteristic quirky techniques to create visual interest or amusement often associated with anime, but that "there's nothing else [in anime] like this where you can do proper acting and realistic mechanical movements. That's why its impression is quite cinematic...In animation, it's very difficult to do something normal. When you consider [Royal Space Force], there are many scenes where the characters are just drinking tea or walking around. You don't take notice of [such actions], yet they're very difficult to draw, and I think it required a lot of challenging work for the key animators."[191] Following Royal Space Force, Masuo would remain closely associated with the works of both Gainax and Anno's later Studio khara as a key animator, technical director, and mechanical designer before his death in 2017.[192]

In January 1986, Toho Towa agreed to distribute Royal Space Force as a feature film, and production assumed a more frantic pace, as the process of in-betweening, cel painting, and background painting began at this time; additional staff was recruited via advertisements placed in anime magazines.[193] Gainax relocated its studio once again, this time from Takadanobaba to a larger studio space in the Higashi-cho neighborhood of Kichijoji, where the remainder of Royal Space Force would be produced.[194] Following the C part of the film, the animation production proceeded in order from the A part (the opening scene through the fight in the air force lounge),[195] to the B part (the arrival at the rocket factory through the funeral for Dr. Gnomm),[196] then to the concluding D part (the General's talk on history to the film's ending).[197][198] The daily exchange of ideas between Yamaga and the other staff at Gainax continued during production, as the artists attempted to understand his intentions, while Yamaga reviewed animation drawings, designs, and background paintings to be re-done in order to get closer to the "image in his head," although this questioning process also continued within Yamaga himself, between concept and expression, or "author versus writer".[199]

"From the first, I did the layouts and drawings with the real thing in mind ... For that purpose, I flew in airplanes and helicopters, [rode in] Type 74 tanks, visited aircraft carriers and NASA. I also witnessed the launch of the Shuttle and exercises of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces. But I had never experienced war, nor did I want to, and for this my references were news footage, videos, and documentary films. What I experienced only through images and words, I accepted as quote, reality, unquote.

—Hideaki Anno, 1987[201]

Although Royal Space Force was essentially a pre-digital animated work[202] using layers of physical cels and backgrounds painted by hand,[203] computers played an important role in its production. Scheduling and accounting on the film was performed using a Fujitsu OASYS100,[204][205] while design drawings were scanned into a NEC PC-9801 which permitted them to be studied at different rotations and for possible color options, using a 256-color palette.[206] Rough draft animation of line drawings testing how sequences would work utilized a Quick Action Recorder computer-controlled video camera, a technology by that point common in the anime industry.[207] Computer-assisted animation seen onscreen in Royal Space Force was used for certain difficult motion shots, including the contra-rotating propellers of the Honnêamise air force plane, the rotation of the space capsule while in orbit, the tilted wheel turn of the street sweeper, and the swing of the instrument needle in the launch control bunker. The motions themselves were rendered using ASCII 3D software, and then traced onto cels.[208] By contast, Ryusuke Hikawa noted that the flakes of frost falling from the rocket at liftoff, which might be assumed to be a CG effect, were done entirely by hand under the supervision of Hideaki Anno.[209]

Anno remarked that two frequent criticisms of Royal Space Force were that "there was no need to make this as an anime" (i.e., as opposed to a live action film), but also contrariwise that "it could have looked more like a [typical] anime;" however, he maintained that both viewpoints missed what had been essential for the film, the intent of which was that the audience perceive reality in an authentic sense. Anno argued that one of the advantages of filmmaking through using 'animation' (he felt it was more accurate in the case of Royal Space Force to speak instead of the advantages of using 'pictures') was the fine degree of control it permitted the creator as a tool for presenting images, and that the high level of detail in the film was not for the sake of imitating live action, but for the conceptual goal of conveying a notion of reality.[210] Anno in fact maintained his concern as an artist on the film was for the "image"[t] rather than the "anime" per se, and that he made a conscious decision not to work in such "so-called animation", as he felt it would be inappropriate for Royal Space Force: "All I can say to people who want to see something more anime-like on their screen is that they should watch other anime."[212]

A one-minute scene of Shiro and Marty conversing on the bed of a truck delivering the Royal Space Force's electromechanical computer, originally meant to precede Shiro's first training run in the capsule simulator, was scripted and animated for the film's B part, but was not included in the theatrical release.[213] The scene was cut for reasons of length before it reached the audio recording stage; however, the 1990 Royal Space Force~The Wings of Honnêamise Memorial Box LaserDisc edition, described by Animage as a kodawari (committed to perfection) project of Bandai co-producer Shigeru Watanabe, would reassemble the film's sound team and voice actors Leo Morimoto and Kazuyuki Sogabe, and record the dialogue and sound effects for the scene.[214] This one-minute scene would also be included on subsequent DVD and Blu-ray editions of Royal Space Force.

Many of the staff of Royal Space Force had also worked on two of the major anime film projects released in 1986: Project A-ko and Castle in the Sky, including Royal Space Force's assistant director Masuo and animation director Yuji Moriyama on A-ko;[215] design artist and key animator Mahiro Maeda had worked on Castle in the Sky,[216] as did Noriko Takaya, who had earlier developed for its director Hayao Miyazaki the "harmony" method used to portray the shifting carapace of the Ohm in Nausicaä; the technique would be used also for the rocket nozzles in Royal Space Force.[u] By the summer of 1986, both works were completed, and a large number of their crew joined the production of Royal Space Force, which by that point was running on a round-the-clock schedule.[220]

Yamaga would later say of the making of Royal Space Force, "it was like we were all swinging swords with our eyes blindfolded".[10] Akai and Yamaga remarked that since they weren't "animation purists," they altered the animation drawings, cels, and timesheets in ways that were not traditional industry practice, to the extent that "the young people who followed in our footsteps in creating anime thought that was how it was done," speculating that they may have created new traditions for anime by breaking the old on the production of Royal Space Force.[221] The idea that Royal Space Force would not use anime's traditional division of labor and strictly assigned roles was developed while it was still in the pre-production stage.[222] Masuo compared Gainax's production system to putting on a school festival, with everyone sharing ideas and participating wherever they could.[223] Higuchi laughed that while as assistant director he supervised with a "blueprint" of what the film would be like, there were times when the finished work turned out to be completely different, and he thought, "Oh..."[224] In 1995, Okada reflected that the film "was made in that kind of chaos ... On a Gainax anime project, everyone has to be a director. Therefore, everyone's feelings and everyone's knowledge are going into it ... That's the good side of how Gainax's films are different from others. But we have no strong director, and that's the weak side."[225] On the director's commentary, Yamaga himself noted that when the film's final retakes were done at the end of 1986, out of 100 adjustments made to scenes, only three were based on the director's own suggestions. Akai had personally rejected other change requests by Yamaga on the basis of representing the opinions of the entire staff and making sure that "everyone was being heard". Yamaga replied, "I was just pleased that everyone was so involved in the project. I hadn't expected that to happen. It was a wonderful time. At the beginning, I was expected to make all the decisions, but as time went by, the staff started to understand that I wasn't going to make all the decisions and that they were going to have to get involved. By the end of the project, nobody cared what I had to say ... I thought that was great."[226]

Cinematography[]

As a pre-digital anime, the scenes in Royal Space Force were created by using a camera to photograph the animation cels and backgrounds onto movie film. A scene would typically consist of a series of separate individual shots known as "cuts," with each cut being prepared for the photographer by collecting into a bag all animation cels and background elements to be used in that particular cut. Akai noted that Anno's animation of the flakes of frost falling from the rocket at liftoff required so many cels[v] that the cuts for the scene were carried in a box, rather than a bag.[228] The director of photography on Royal Space Force was Hiroshi Isakawa of Mushi Production, where the animation for the pilot film had been shot in early 1985.[63] Isakawa had subsequently been asked to direct photography on the full-length film as well; in an interview after the film's completion, he remarked that he was originally assured photography could begin in April 1986, but received no cuts to film[w] until August and September, and then "only the easy work," with Gainax putting off completing the more difficult scenes until later.[x] Isakawa joked that as it was not until October that the cuts began to come in at a steady pace, it was difficult for him to determine exactly how much progress they were making on the film. The most intense period of work occurred in January 1987; Isakawa completed the filming for Royal Space Force at the end of that month, noting that with the off-and-on nature of the task, the photography had taken three months of actual time.[232]

Besides the technical necessity to photograph the animation, Gainax's own prior experience in filming amateur live-action works had a broader influence on the construction of the animated scenes themselves; the sequence early in Royal Space Force where Tchallichammi and Shiro converse in the bathroom is described in the director's commentary as a "simple scene" which was nevertheless redone many times as the staff debated the relative motions and placement of the two characters "as if we were shooting this in live-action."[233] Akai and Yamaga remarked that it had not been their intent as animators to "emulate" live-action films, but rather to make animation with a realism based on their experience of "look(ing) through the camera lens to see what it sees ... there weren't many people who could [both] draw and understand how the camera works ... It's difficult to express animated films realistically. The camera doesn't really exist."[234] Another reflection of their live-action experience involved building scale models of Marty's motorcycle, the Honnêamise naval jet and air force prop planes, and the Royal Space Force headquarters building. These models were used as reference aids for the animators,[y] but also to choose which angles and viewpoints to use in scenes where the modelled objects would appear; in the figurative sense, to "decide where the cameras should be."[236]

Many of the scenes in the film would be created through special photographic techniques applied to the underlying animation; an example was the appearance of the television screen in the Royal Space Force barracks. Gainax came up with the idea to take a clear acrylic panel cover from a fluorescent lamp and place it over the animation cels depicting the TV broadcast, moving the cover around as the cels were photographed; the motion of the prismatic pattern on the cover simulated the look of an image with varying reception quality. The appearance and disappearance of an analog television's cathode ray-generated images as a channel was switched or the set turned off was further simulated by using a photo compositing technique, as it was felt employing a simple camera fade would reduce the realism of the effect.[237] The TV screen images were shot at the T Nishimura studio, a photography specialist that would later contribute to 1989's Patlabor: The Movie.[238]

Isakawa described the technical challenges he faced in filming Gainax's work on Royal Space Force, with some individual cuts created by using as many as 12 photographic levels consisting of cels, superimposition layers, and sheets of paper masks designed to capture isolated areas of different colored transmitted light (a photographic technique useable with translucent items such as animation cels, where the image can also be illuminated by light passing through the object, rather than only by reflected light). Some of the cel layers arrived with dust and scratches, which posed additional difficulties for Isakawa; he considered obscuring them with the popular method of employing a polarizing filter, but felt he could not use the technique, as such filters also obscured fine details in the cel art. Isakawa remarked that Gainax had however largely avoided what he described as the common errors in the anime industry of cels not being long enough for their background paintings, or having misaligned attachment points to peg bars.[239] Another challenging aspect for Isakawa involved motion rather than light, such as conveying the heavy vibrations of Marty's motorcycle, or the air force plane cockpit; whereas ordinarily such scenes would be filmed while shaking the cels and the backgrounds as a unit, Gainax insisted that the elements be shaken separately.[240]

Yamaga and Shinji Higuchi, who also served as assistant director of photography on the film,[241] had Isakawa watch The Right Stuff and showed him NASA photos as a reference for the look they wished to achieve in certain shots. In an effort to convey a sense of the visual mystery of the film's world from space, Isakawa photographed the animation art through such tiny holes made in the paper masks for transmitted light that he felt the images could hardly be said to be lit at all; he was unable to judge the exact light levels needed in advance, having to make adjustments afterwards based on examining the developed film.[242] Higuchi related that he had made the holes using an acupuncture needle he had obtained from a masseur on the film's staff.[243][z] Isakawa mentioned that he would get tired and angry after being asked to shoot five or six different takes of a cut, not seeing the necessity for it, but gave up resisting when he realized it was a work "in pursuit of perfection," and felt that the final achievement was "realistic without using the imagery of live action, a work that made full use of anime's best merits."[245]

Iwao Yamaki of the studio Animation Staff Room, who had been director of photography on Harmagedon and The Dagger of Kamui,[246] served as photography supervisor on Royal Space Force, assisting Isakawa and Yamaga with advice on specific shooting techniques; his suggestions included the fog effect in the sauna where the Republic officials discuss the Honnêamise kingdom's launch plans, achieved by photographing the cels through a pinhole screen, and creating the strata of thin clouds that Shiro's training flight flies through using a slit-scan method.[247] Isakawa and Yamaki were both 20 years older than Yamaga;[248] Yamaki remarked that Gainax's filmmaking without knowledge of established techniques opened the possibility of "many adventures," and whereas his generation had adventures through what they already knew, Yamaki wanted the next generation of filmmakers to have "different adventures," that necessitated taking new risks. Yamaki approvingly quoted Yamaga that the nature of Royal Space Force as a film was not defined by the fact it was an anime, but through how it used the techniques of anime to the fullest extent to ultimately achieve filmic effects beyond if it had been a live-action work, which Yamaga believed was the way for anime to prove its value as a cinematic medium.[249]

Voice acting[]

The voice performances in Royal Space Force were supervised by Atsumi Tashiro of the anime studio Group TAC. Tashiro, who had been sound director for the highly influential 1974 TV series Space Battleship Yamato[250] and subsequent Yamato movies, as well as for the 1985 Gisaburo Sugii film Night on the Galactic Railroad,[251] remarked that in the more than 20 years of his career, Royal Space Force was the first time he had agreed to direct the sound for a work made outside his own company. Gainax had been enthusiastic in pursuing Tashiro's involvement, first sending him the script of the film, followed by a visit from Yamaga and Okada to explain the script, after which, Tashiro joked, he still couldn't understand it, even with several follow-up meetings. Despite his initial difficulty in grasping the project, however, Tashiro was struck by the passion and youth of the filmmakers, and felt that working with them on Royal Space Force would represent an opportunity to "revitalize" himself professionally.[252] Tashiro's relationship with the studio would continue after the film into Gainax's next two productions: their first OVA series Gunbuster, which modeled the character Captain Tashiro upon him, and their debut TV show, Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water, in which Group TAC was closely involved.[253]

In the director's commentary, Yamaga remarked that he "wanted the dialogue to be natural," which he maintained was "a first in Japanese animation." Akai felt that a tone had been set for Royal Space Force by the decision to cast Leo Morimoto in the lead role as Shirotsugh: "The other actors knew that this was going to be a different kind of animated film when we cast Leo."[254] Morimoto was a 43-year old veteran actor in live-action films and TV[255] but had very limited experience in anime, whereas Mitsuki Yayoi, cast as Riquinni after Gainax had heard her on the radio,[256] was a stage actor and member of the Seinenza Theater Company with some voice-over experience,[255] but who had never before played an anime role.[257] While remarking that there were already many professional voice actors who were suited to animation work, Tashiro saw the casting of Morimoto and Yayoi as a great opportunity for him, asserting that the apprehension the performers felt due to their mutual unfamiliarity with the field meant that they approached their roles as an actual encounter, with genuine emotion and reactions that were honest and fresh, a spirit that Tashiro said he had forgotten within the world of anime.[258]

Morimoto remarked during a recording session for the film in late November 1986 that Tashiro directed him not to play the role of Shirotsugh as if it were an anime, but rather to attempt the flavor of a live performance,[259] noting in a later interview that Yamaga had given him the same instructions. He commented that it was a difficult role for him, as unlike a live-action drama, "you can't fake the mood, you have to express yourself correctly with just your voice," and viewed his work on Royal Space Force as "scary" but "fulfilling."[260] Although evaluating the character himself as "not a great hero," Morimoto at the same time said that he found much that was convincing in Shirotsugh's growth in the film, feeling that it somehow came to assume the role of history's own progression: "What is to be found at the end of that maturation is gradually revealed, arriving at a magnificent place." He added he was "shocked that a 24-year old could make such a film ... I'm glad to know that [creators] like this are making their debut, and I hope that more of them do." Asked what he wanted people to particularly watch for in the film, Morimoto answered that most adults, by which he included himself, "talk a lot about 'young people these days,' and so forth. But the truth is these young people who hear that from us are able to be clear about this world with an ease adults no longer possess. They have a firm grasp of history, and they don't shy away from the parts in this film that adults have avoided; they call out the lies, while at the same time, each one of them puts in their work with sincerity."[261]