Sculpture in the Indian subcontinent

| Art forms of India |

|---|

|

| By religion |

| By period |

| By technique |

| By location |

| See also |

|

Sculpture in the Indian subcontinent, partly because of the climate of the Indian subcontinent makes the long-term survival of organic materials difficult, essentially consists of sculpture of stone, metal or terracotta. It is clear there was a great deal of painting, and sculpture in wood and ivory, during these periods, but there are only a few survivals. The main Indian religions had all, after hesitant starts, developed the use of religious sculpture by around the start of the Common Era, and the use of stone was becoming increasingly widespread.

The first known sculpture in the Indian subcontinent is from the Indus Valley civilization, and a more widespread tradition of small terracotta figures, mostly either of women or animals, which predates it.[1] After the collapse of the Indus Valley civilization there is little record of larger sculpture until the Buddhist era, apart from a hoard of copper figures of (somewhat controversially) c. 1500 BCE from Daimabad.[2] Thus the great tradition of Indian monumental sculpture in stone appears to begin relatively late, with the reign of Asoka from 270 to 232 BCE, and the Pillars of Ashoka he erected around India, carrying his edicts and topped by famous sculptures of animals, mostly lions, of which six survive.[3] Large amounts of figurative sculpture, mostly in relief, survive from Early Buddhist pilgrimage stupas, above all Sanchi; these probably developed out of a tradition using wood that also embraced Hinduism.[4]

During the 2nd to 1st century BCE in far northern India, in the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara from what is now southern Afghanistan and northern Pakistan, sculptures became more explicit, representing episodes of the Buddha's life and teachings.

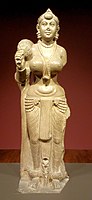

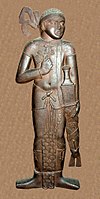

The pink sandstone Hindu, Jain and Buddhist sculptures of Mathura from the 1st to 3rd centuries CE reflected both native Indian traditions and the Western influences received through the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara, and effectively established the basis for subsequent Indian religious sculpture.[4] The style was developed and diffused through most of India under the Gupta Empire (c. 320–550) which remains a "classical" period for Indian sculpture, covering the earlier Ellora Caves,[5] though the Elephanta Caves are probably slightly later.[6] Later large scale sculpture remains almost exclusively religious, and generally rather conservative, often reverting to simple frontal standing poses for deities, though the attendant spirits such as apsaras and yakshi often have sensuously curving poses. Carving is often highly detailed, with an intricate backing behind the main figure in high relief. The celebrated bronzes of the Chola dynasty (c. 850–1250) from south India, many designed to be carried in processions, include the iconic form of Shiva as Nataraja,[7] with the massive granite carvings of Mahabalipuram[8] dating from the previous Pallava dynasty.[9]

Bronze age sculpture[]

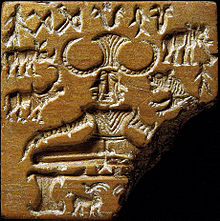

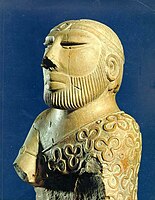

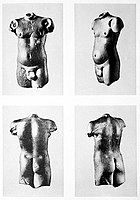

The first known sculpture in the Indian subcontinent is from the Indus Valley civilization (3300–1700 BCE). These include the famous small bronze Dancing Girl. However such figures in bronze and stone are rare and greatly outnumbered by pottery figurines and stone seals, often of animals or deities very finely depicted.[10]

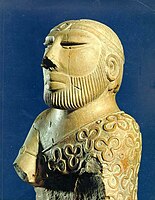

The Priest-King, Mohenjo-daro

Dancing Girl , Mohenjo-daro

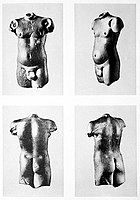

Harappan jasper torso

The second Dancing Girl bronze figure

Daimabad Chariot

Woman riding two bulls (bronze), from Kausambi, c. 2000-1750 BCE

Pre-Mauryan art[]

Some very early depictions of deities seem to appear in the art of the Indus Valley Civilisation (3300 BCE - 1700 BCE), but the following millennium, coinciding with the Vedic period, is devoid of such remains.[11] It has been suggested that the early Vedic religion focused exclusively on the worship of purely "elementary forces of nature by means of elaborate sacrifices", which did not lend themselves easily to anthropomorphological representations.[12]

Various artefacts may belong to the Copper Hoard Culture (2nd millennium BCE), some of them suggesting anthropomorphological characteristics.[13] Interpretations vary as to the exact signification of these artifacts, or even the culture and the periodization to which they belonged.[13] Some examples of artistic expression also appear in abstract pottery designs during the Black and red ware culture (1450-1200 BCE) or the Painted Grey Ware culture (1200-600 BCE), with finds in a wide area.[13]

Most of the early finds following this period correspond to what is called the "second period of urbanization" in the middle of the 1st millennium BCE, after a gap about a thousand years following the collapse of the Indus Valley Civilization.[13] The anthropomorphic depiction of various deities apparently started in the middle of the 1st millennium BCE, possibly as a consequence of the influx of foreign stimuli initiated with the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley, and the rise of alternative local faiths challenging Vedism, such as Buddhism and Jainism and local popular cults.[11] Some rudimentary terracotta artifacts may date to this period, just before the Mauryan era.[14]

Art of the Mauryan period[]

The surviving art of the Mauryan Empire which ruled, at least in theory, over most of the Indian subcontinent between 322 and 185 BCE is mostly sculpture. There was an imperial court-sponsored art patronized by the emperors, especially Ashoka, and then a "popular" style produced by all others.

The most significant remains of monumental Mauryan art include the remains of the royal palace and the city of Pataliputra, a monolithic rail at Sarnath, the Bodhimandala or the altar resting on four pillars at Bodhgaya, the rock-cut chaitya-halls in the Barabar Caves near Gaya, the non-edict bearing and edict bearing pillars, the animal sculptures crowning the pillars with animal and botanical reliefs decorating the abaci of the capitals and the front half of the representation of an elephant carved out in the round from a live rock at Dhauli.[15]

This period marked the appearance of Indian stone sculpture; much previous sculpture was probably in wood and has not survived. The elaborately carved animal capitals surviving on from some Pillars of Ashoka are the best known works, and among the finest, above all the Lion Capital of Ashoka from Sarnath that is now the National Emblem of India. Coomaraswamy distinguishes between court art and a more popular art during the Mauryan period. Court art is represented by the pillars and their capitals,[16] and surviving popular art by some stone pieces, and many smaller works in terracotta.

The highly polished surface of court sculpture is often called Mauryan polish. However this seems not to be entirely reliable as a diagnostic tool for a Mauryan date, as some works from considerably later periods also have it. The Didarganj Yakshi, now most often thought to be from the 2nd century CE, is an example.

The Pataliputra capital, showing both Achaemenid and Greek influence, with volute, bead and reel, meander and honeysuckle designs. Early Mauryan period, 4th-3rd century BC.

Masarh lion sculpture

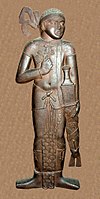

Mauryan statue 3rd-2nd century BCE

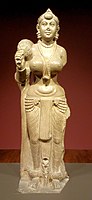

Yaksha statue

Didarganj Yakshi

Art of the Shunga period (180-80 BCE)[]

Terracotta arts executed during pre-Mauryan and Mauryan periods are further refined during Shunga periods and Chandraketugarh emerge as an important center for the terracotta arts of Shunga period. Mathura which has its basis in the pre-Mauryan period also emerges as an important center for Jain, Hindu and Buddhist art.

Bharhut stupa, Shunga horseman

Shunga Yakshi

Chandraketugarh figurine

Male figure, Chandraketugarh, India, 2nd-1st century BCE

Bharhut Yavana(Greek) Warrior

Satavahana art[]

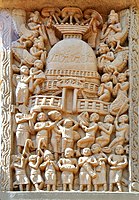

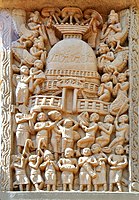

The Satavahana dynasty ruled much of the Deccan and sometimes other areas, including Maharashtra, between about the 2nd-century BCE and 2nd century CE. They were a Buddhist dynasty, and the most significant remains of their sculptural patronage are the Sanchi and Amaravati Stupas,[18] along with a number of rock-cut complexes.

Sanchi stupas were constructed by Emperor Ashoka and later expanded by Shungas and Satavahanas. Major work on decorating the site with Torana gateway and railing was done by Satavahana Empire.

Sanchi gateway

Carved reliefs of Sanchi gateway

Satavahana relief regarding the city of Kusinagara in the war over the Buddha's relics, South Gate, Stupa no. 1, Sanchi

Bimbisara with his royal cortege issuing from the city of Rajagriha to visit the Buddha.

Foreigners making a dedication to the Great Stupa at Sanchi.

Cave temples[]

Between the 2nd century BCE and 2nd century CE under Satavahanas, several Buddhist caves propped up along the coastal areas of Maharashtra and these cave temples were decorated with Satavahana era sculptures and hence not only some of the earliest art depictions, but evidence of ancient Indian architecture.

Kanheri caves Buddha statue

Kanheri caves statue

Amaravathi art[]

The Amaravati school of Buddhist art was one of the three major Buddhist sculpture centres along with Mathura and Gandhara and flourished under Satavahanas, many limestone sculptures and tablets which once were plastered Buddhist stupas provide a fascinating insight into major early Buddhist school of arts.

Amaravati Marbles, fragments of Buddhist stupa

Head of a lion, from Gateway pillar at the Amaravati Stupa

Scroll supported by Indian Yaksha, Amaravati, 2nd–3rd century CE

Mara's assault on the Buddha, 2nd century CE, Amaravati

Early South India[]

Stone sculpture was much later to arrive in South India than the north, and the earliest period is only represented by the lingam with a standing figure of Shiva in the village of Gudimallam, in the southern tip of Andhra Pradesh. The "mysteriousness" of this "lies in the total absence so far of any object in an even remotely similar manner within many hundreds of miles, and indeed anywhere in South India".[19] It is some 5 ft in height and one foot thick; the penis is relatively naturalistic, with the glans shown clearly. The stone is local, and the style described by Harle as "Satavahana-related".[19] It is dated to the 3rd century BCE,[20] or 2nd/1st century BCE.[19]

Though the hardness of local granites, the relatively limited penetration of Buddhism and Jainism in the deep south, and a presumed persistent preference for wood have all been proposed as factors in the late development of stone architecture and sculpture in the south, "the mystery remains".[21] The form of the Gudimallam linga, for example, would be a natural one to evolve in wood, using a straight tree trunk very efficiently, but to say that it did so is pure speculation in our present state of knowledge. Wooden sculpture, and architecture, has remained common in Kerala, where stone is hard to come by, but this means survivals are very largely limited to the last few centuries.[22]

Kushana art[]

("Year 4 of the Great King Kanishka")