Secession (art)

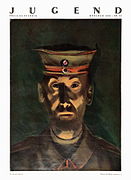

Paul Hoecker's 1901 cover for the influential Munich-based magazine Die Jugend that inspired the Jugendstil Secession. | |

| Years active | Late 19th and early 20th century |

|---|---|

| Country | Begun in France, concentrated in Germany and Austria |

| Major figures | Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Franz Stuck, Otto Eckmann, Gustav Klimt, Max Liebermann, Egon Schiele, Otto Dix |

| Influences | The French Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts secession and other Modernist art, including Art Nouveau, Dada, Impressionism, folk art native to the region and African and Asian art |

| Influenced | Later art movements, including the International Style, Bauhaus, and Art Deco |

In art history, secession refers to an historic break between a group of avant-garde artists and conservative European standard-bearers of academic and official art in the late 19th and early 20th century.[1] The term was almost certainly inspired by the history of annexation, secession and dissolution in the city-states of Central Europe, prior to the late 1800s.[2] The name was first suggested by Georg Hirth (1841–1916),[3] the editor and publisher of the influential German art magazine Jugend (Youth), which also went on to lend its name to the Jugendstil. His word choice emphasized the tumultuous rejection of legacy art while it was being reimagined.[4][5][6]

Of the various secessions, the Vienna Secession (1897) remains the most influential. Led by Gustav Klimt, who favored the ornate Art Nouveau style over the prevailing styles of the time,[5] it was inspired by the Munich Secession (1892), and the nearly contemporaneous Berlin Secession (1898), all of which begot the term Sezessionstil, or "Secession style."[5]

Hans-Ulrich Simon later revisited that idea in Sezessionismus: Kunstgewerbe in literarischer und bildender Kunst, the thesis he published in 1976.[7] Simon argued that the successive waves of art secessions in the late 19th and early 20th century Europe collectively form a movement best described by the all-encompassing term "Secessionism."

By convention, the term is usually restricted to one of several secessions — mainly in Germany, but also in Austria and France — coinciding with the end of the Second Industrial Revolution,[8] World War I and early Weimar Germany.[9]

Artists and their art[]

The first secession, known as the Salon du Champs-de-Mars (1890–present), is named after the 1791 Champ de Mars Massacre that saw dozens of civilians killed at the hands of the military, which radicalized the Paris citizenry – and the Salon's organizers were likely hoping for a similarly revolutionary effect.[10] Eager to curate their own work, Puvis de Chavannes and Auguste Rodin declared independence by forming a break-away group, which was a ground-breaking departure in a culture with salon traditions dating back to the early 1700s.[11] Unlike subsequent secessions, Chavannes' group sought higher standards and a more conservative approach, not a more liberal one.[11] Over the next several years, artists in various European countries followed in the Salon's footsteps, likewise "seceding" from traditional art movements and follow their own diktats.[9]

The Vienna Secession, founded in 1897, is the most famous of these groups. Although the Austrian Gustav Klimt is one of its most well-known members, the group also included Czech Alphonse Mucha, Croatian sculptor Ivan Mestrovic and the Polish artists Jozef Mehoffer, Jacek Malczewski and Stanislaw Wyspianski,[12] the latter of whom were invited to join the Secession in its opening year, as well as write for Ver Sacrum, the Secession magazine Klimt founded, which spread the influence of Art Nouveau.[12] Curvilinear geometric shapes and patterns of that period are typical of it. Artists reveled in the movement's broad visual vocabulary. Their work spanned the arts — painting, decor, architecture, graphic design, furniture, ceramics, glassware and jewelry — at times naturalistic, at times stylized.[5]

Founded in 1919, the Dresden Secession stands in contrast to the Vienna Secession. While the Viennese version is known for its beauty, Dresden's version is known for its politics and its post-expressionist rejection of romanticized aesthetics. The New Objectivist and German Expressionist styles of artists like Otto Dix and Conrad Felixmüller were hardened by the horrors of the First World War, and replete with criticism of Weimar Germany.[13][14][15] The Nazis would later condemn both artists.[13][14][15] Although the Dresden Secession officially dissolved in 1925, many of its artists continued pursuing careers into the 1930s and beyond, even while the Nazis began "cleansing" the culture of the Modernist art and artists they deemed offensive.[16] Their "purification" program included displacing Modernist art in Germany's museums with an earlier style of rigid Realism and an Apollonian “classical” style that glorified the Third Reich.[4][13][17][18]

In 1937, while planning a major exhibition of "pure" art, Joseph Goebbels, Hitler's Reich Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, also conceived of a Degenerate Art Exhibition, which ultimately featured 650 works of art confiscated from 32 different museums – and then sold for profit.[16][13] "Degeneracy" was an entrenched policy by then, a useful way for Hitler, who twice failed to matriculate into art school, to routinely sanction other artists.[16][18] At that point, artists who could fled, those who couldn't were later deported to concentration camps.[16][19] Some, like Berlin Secessionist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, committed suicide.[19] Still others collaborated.[17][18]

In 1945, the last year of World War II, the British and American bombing of (civilian) Dresden controversially left the city, an arts and cultural landmark, known for both the Dresden Secession and the turn-of-the-century Expressionist art movement Die Brücke, in ruins.[20]

Portraits[]

(Selection was limited by availability.)

French painter Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824–1898) circa 1880. → Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts

German painter, sculptor, printmaker, and architect Franz Stuck (1863–1928) self-portrait, 1923. → Munich Secession

Lovis Corinth (1858-1925) portrait of German painter and graphic artist Otto Eckmann (1865–1902), painted in 1897. → Jugendstil

German painter Max Liebermann (1847–1935), painted in 1925. → Berliner Secession

Austrian painter Egon Schiele (1890–1918) self-portrait from 1910. → Sonderbund westdeutscher Kunstfreunde und Künstler

Portrait of German painter and printmaker Otto Dix (1891–1969) by Hugo Erfurth, circa 1933. → Dresden Secession

Movements[]

Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts[]

Paris (1890–present) — Known for its role in decisively ending the stranglehold the state had on the salon exhibition system, the rebel Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts formed in reaction to the Société des artists français.[21] The revolt led by Puvis de Chavannes, Ernest Meissonier, Carolus-Duran and Carrier-Belleuse helped radicalize the Central European art world.

The Munich Secession[]

Munich (1892–1938 and 1946–present) — Also known as the Association of Visual Artists of Munich, the Munich Secession formed in response to stifling conservatism from the Munich Artists' Association, the Academy of Fine Arts and, most notably, the art foundation dedicated to history painting in service to the state, known as Prinzregent-Luitpold-Stiftung zur Förderung der Kunst, des Kunstgewerbes und des Handwerks in München.[1] Key figures in the movement included Bernhard Buttersack, Ludwig Dill, Bruno Piglhein, Ludwig von Herterich, Paul Hoecker, Albert von Keller, Gotthardt Kuehl, Hugo von Habermann, Robert Poetzelberger, Franz von Stuck, Fritz von Uhde and Heinrich von Zügel.[1] They are best known for a breakout exhibition after seeking economic and artistic self-determination, which included forming a cooperative.[1] Although the group was dissolved amid the Nazi art purges, they were re-established in 1946, and celebrated their centennial in 1992.[1]

The Jugendstil (Youth Style)[]

Munich, Weimar and Germany's Darmstadt Artists' Colony (1895–1910) — They were formed to resist the official and academic emphasis on historicism and neoclassicism in art, while instead pursuing a perfect blend of fine and applied arts. Jugendstil design often included the "floral motifs, arabesques, and organically inspired lines" of the Vienna Secession.[22] Its practical edge, however, was wholly its own, as it matched designers with "industrialists for mass production to disseminate products." That practicality undoubtedly influenced its increasing abstraction and interest in functionality, initially showcased in the illustrations and graphic design of its best-known designer Otto Eckmann in magazines like Jugend and Simpicissimus and Pan.[9][22] Like its Viennese counterpart, artists like Hermann Obrist, Henry van de Velde, Bernhard Pankok and Richard Riemerschmid also produced architecture, furniture, and ceramics. But unlike Vienna, it diverged sufficiently to provide the foundations for Bauhaus. "Principles of standardization of materials, design, and production" that, for example, architect Peter Behrens pioneered in pursuit of Gesamtkunstwerk (a complete work of art) were later passed on to his three most famous students: Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius.[22]

The Vienna Secession[]

Vienna (1897–1905) — The most famous secession was the Vienna Secession formed in reaction to the Association of Austrian Artists. Leading figures included Gustav Klimt, Josef Hoffman, Koloman Moser and Otto Wagner. They are known for their painting, furniture, glass and ceramics, as well as the Secession Building the architect Joseph Maria Olbrich's designed in Vienna, and the magazine Ver Sacrum, founded by Klimt.

The Berlin Secession[]

Berlin (1899–1913) — The Berlin Secession formed in reaction to the Association of Berlin Artists, and the restrictions on contemporary art imposed by Kaiser Wilhelm II, 65 artists "seceded" to create and exhibit new work, sometimes linked by terms like "Berlin Impressionism," or "German Post-Impressionism," in both cases reflecting the influence of French Impressionism, which had spread internationally.[9] They are also known for their conceptual art, as well as an internal split in the group which led to the formation of a New Secession (1910–1914). Key figures included Walter Leistikow, Franz Skarbina, Max Liebermann, Hermann Struck, and the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch.[9][23][24]

The Sonderbund westdeutscher Kunstfreunde und Künstler[]

Cologne (1909–1916) — Also known as the "Sonderbund" or the "Separate League of West German Art Lovers and Artists," the Sonderbund westdeutscher Kunstfreunde und Künstler was known for its landmark exhibitions introducing French Impressionism, Post-Impressionism and Modernism to Germany.[25] Its 1912 show aimed to organize "the most disputed paintings of our time," and was later credited for helping develop a German version of Expressionism while also presenting the most significant exhibition of European Modernism prior to World War I."[26] The following year, in fact, it inspired a similar show in New York.[26] Artists associated with the group included Julius Bretz, Max Clarenbach, August Deusser, Walter Ophey, Ernst Osthaus, Egon Schiele, Wilhelm Schmurr, Alfred Sohn-Rethel, Karli Sohn-Rethel and Otto Sohn-Rethel, along with collectors and curators of art.[26]

The Dresden Secession[]

Dresden (1919–1925) — Formed in reaction to the oppression of post World War I and the rise of the Weimar Republic, Otto Schubert, Conrad Felixmüller and Otto Dix are considered key figures in the Dresden Secession. They are known for a highly accomplished form of German Expressionism that was later labeled "Degenerate" by the Nazis.

Periodicals[]

(Selection was limited by availability.)

Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts — A Salon de Champ-de-Mars catalogue, noting that one catalogue a year, of two, would be dedicated to work from the new Paris Salon, 1893.

Vienna Secession — Alfred Roller's cover for the January issue of Ver Sacrum magazine, 1898.

Munich Secession — Franz von Stuck's cover illustration for Pan (magazine), April/May 1895.

Jugendstil — Konrad Westermayr's painting "Self-Portrait with FIeld Cap," published on the cover of issue 32 of "Jugend" magazine in 1930.

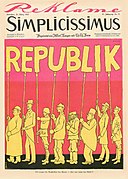

Munich Secession — Historical cartoon despicting the Weimar Republic as a 'republic without republicans.' Published in the politically daring and visually modern magazine Simplicissimus on 21 March 1927.

The Weimar Republic — Degenerate Art (Entartete Kunst) exhibition catalogue, showing work by Johannes Molzahn, Jean Metzinger, and Kurt Schwitters in 1937.

References[]

- ^ a b c d e "Munich Secession: Avant-Garde Artists Association". www.visual-arts-cork.com. Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- ^ "Unification of German States - Countries - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved 2021-10-21.

- ^ Powell, Nicolas (1976). "Review of Ver Sacrum 1898-1903". The Burlington Magazine. 118 (882): 660–660. ISSN 0007-6287.

- ^ a b Danzker, Jo-Anne Birnie. "The Munich Secession Demystified". Frye Art Museum. Retrieved 2021-01-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d Rosenman, Roberto (2017). "The Vienna Secession: A History". The Vienna Secession. Retrieved 2021-01-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "The illustrated guide to Helsinki's Art Nouveau and Jugendstil architecture". Helsinki Jugendstil. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Sezessionismus. Kunstgewerbe in literarischer und bildender Kunst. von Simon, Hans-Ulrich.: (1976) | Georg Fritsch Antiquariat". www.zvab.com. Retrieved 2021-01-12.

- ^ "Industrial Revolution | Definition, History, Dates, Summary, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-01-18.

- ^ a b c d e "The Artist Hermann Struck and His Work: From the Berlin Secession to the Landscapes of Israel". web.nli.org.il. Retrieved 2021-01-11.

- ^ "The Champ de Mars massacre". French Revolution. 2020-08-31. Retrieved 2021-01-19.

- ^ a b "Paris Salon". www.visual-arts-cork.com. Retrieved 2021-01-19.

- ^ a b "Polish Art Nouveau | Mloda Polska". www.local-life.com. Retrieved 2021-01-19.

- ^ a b c d Cotter, Holland (2014-03-13). "First, They Came for the Art (Published 2014)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- ^ a b Schjeldahl, Peter. "Dark Pleasures". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- ^ a b Holocaust Encyclopedia. ""Degenerate" Art". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 2021-01-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d Budanovic, Nikola (2018-01-27). "Degenerate Art Exhibition - When Hitler Declared War on Modern Art". WAR HISTORY ONLINE. Retrieved 2021-01-19.

- ^ a b Filkins, Dexter. "Inside the U.S. Army's Warehouse Full of Nazi Art". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- ^ a b c O’Connor, William (2014-11-30). "The Modern Artists the Nazis Favored". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 2021-01-19.

- ^ a b Michalska, Magda (2016-08-27). "4 Of Hitler's Least Favourite 'Degenerate' Artists (There Were Many More)". DailyArtMagazine.com - Art History Stories. Retrieved 2021-01-19.

- ^ S., H. W. (1910). "Art in Germany". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. 18 (91): 65–66. ISSN 0951-0788. JSTOR 858498.

- ^ "Paris Salons (1673–present)". The Art Institute of Chicago. Retrieved 2021-01-11.

- ^ a b c "Jugendstil Movement Overview". The Art Story. Retrieved 2021-01-22.

- ^ Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. "Berlin Impressionism: Works from the Berlin Secession from the National Gallery in Berlin" (PDF). GDKE Berliner Impressionisten.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Post-Impressionism in Germany (1880-1910)". www.visual-arts-cork.com. Retrieved 2021-01-22.

- ^ Willette, Jeanne. "German Expressionism | Art History Unstuffed". Retrieved 2021-01-22.

- ^ a b c Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "1912 show that shook art world returns to Cologne | DW | 20.09.2012". DW.COM. Retrieved 2021-01-22.

Bibliography[]

- Simon, Hans-Ulrich: Sezessionismus. Kunstgewerbe in literarischer und bildender Kunst, J. B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart 1976 ISBN 3-476-00289-6

- French art

- 19th-century French artists

- French artist groups and collectives

- German art

- 20th-century German architects

- 19th-century German artists

- German artist groups and collectives

- Austrian art

- 20th-century Austrian artists

- 19th-century Austrian artists

- Austrian artist groups and collectives

- Belgian artist groups and collectives

- Art Nouveau

- 20th-century German painters

- Graphic design

- Graphic artists

- Typography