Second Vienna Award

hideThis article has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Hungarian Foreign Minister István Csáky signing the agreement, with Romanian Foreign Minister Mihail Manoilescu next to him | |

| Signed | 30 August 1940 |

|---|---|

| Location | Belvedere Palace, Vienna, Germany |

| Signatories | |

| Parties | |

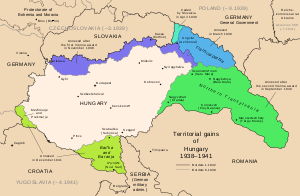

The Second Vienna Award, also known as the Vienna Diktat,[1] was the second of two territorial disputes that were arbitrated by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. On 30 August 1940, they assigned the territory of Northern Transylvania, including all of Maramureș and part of Crișana, from Romania to Hungary.[2]

Background[]

After World War I, the multiethnic Kingdom of Hungary was divided by the 1920 Treaty of Trianon to form several new nation-states, but Hungary claimed that the new state borders did not follow the real ethnic boundaries. The new nation-state of Hungary was about a third the size of prewar Hungary, and millions of ethnic Magyars were left outside the new Hungarian borders. Many historically-important areas of Hungary were assigned to other countries, and the distribution of natural resources was uneven as well. The various non-Magyar populations of the old kingdom generally saw the treaty as justice for the historically-marginalized nationalities, but Hungarians considered the treaty to have been deeply unjust, a national humiliation and a real tragedy.

The treaty and its consequences dominated Hungarian public life and political culture in the interwar period. Moreover, the Hungarian government swung more and more to the right. Eventually, under Regent Miklós Horthy, Hungary established close relations with Benito Mussolini's Italy and Adolf Hitler's Germany.

The alliance with Nazi Germany allowed Hungary to regain southern Czechoslovakia in the First Vienna Award of 1938 and Subcarpathia in 1939. However, neither that nor the subsequent military conquest of Carpathian Ruthenia in 1939 satisfied Hungarian political ambitions. The awards allocated only a fraction of the territories lost by the Treaty of Trianon, and the loss that the Hungarians resented the most was that of Transylvania, which had been ceded to Romania.

At the end of June 1940, the Romanian government gave in to a Soviet ultimatum and allowed Moscow to take over both Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina, which had been incorporated into Romania after World War I, as well as the Hertza region. Though the territorial loss was dreadful from its perspective, the Romanian government preferred it to a military conflict, which it knew it could not win, with the USSR. However, the Hungarian government interpreted the fact that Romania permanently gave up some areas as an admission that it was no longer insisting on keeping its national territory intact under pressure. The Soviet occupation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina thus inspired Budapest to escalate its efforts to resolve "the question of Transylvania". Hungary hoped to gain as much of Transylvania as possible, but the Romanians would have none of that and submitted only a small region for consideration. Eventually, Hungarian-Romanian negotiations fell through entirely.

As a result, Romania and Hungary were "browbeaten" into accepting Axis arbitration.[3]

Meanwhile, the Romanian government had acceded to Italy's request for territorial cessions to Bulgaria, another German-aligned neighbor. On 7 September, under the Treaty of Craiova, the "Cadrilater" (southern Dobruja) was ceded by Romania to Bulgaria.

Award[]

On 1 July 1940, Romania repudiated the Anglo-French guarantee of 13 April 1939, which had become worthless as a result of France's collapse. The next day, King Carol II addressed a letter to Hitler to suggest for Germany to send a military mission to Romania and to renew the alliance of 1883. Germany used Romania's new desperation to force a revision of the territorial settlement produced by the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 in favour of Germany's old allies, Hungary and Bulgaria. In an exchange of letters between Carol and Hitler (5–15 July), the former insisted for no territorial exchange to occur without a population exchange, and the latter conditioned German goodwill towards Romania on Romania's having good relations with Hungary and Bulgaria.[4] The Romanian foreign minister was Mihail Manoilescu; the German minister plenipotentiary in Bucharest was Wilhelm Fabricius.

In accordance with German wishes, Romania began negotiations with Hungary at Turnu Severin on 16 August.[5] The initial Hungarian claim was 69,000 km2 (27,000 sq mi) of territory with 3,803,000 inhabitants, almost two thirds of whom were Romanian. Talks were broken off on 24 August. The German and Italian governments then proposed an arbitration, which was characterised in the minutes of the Romanian Crown Council of 29 August as "communications with an ultimative character made by the German and Italian governments".[5] The Romanians accepted, and Foreign Ministers Joachim von Ribbentrop of Germany and Galeazzo Ciano of Italy met on 30 August 1940 at the Belvedere Palace, in Vienna. They reduced the Hungarian demands to 43,492 km2 (16,792 sq mi), with a population of 2,667,007.[6] The treaty was signed by Hungarian Foreign Minister István Csáky and Romanian Foreign Minister Mihail Manoilescu. A Romanian crown council met overnight on 30–31 August to accept the arbitration. At the meeting, Iuliu Maniu demanded for Carol to abdicate and for the Romanian army to resist the Hungarian takeover of northern Transylvania. His demands were pragmatically rejected.[5]

Population statistics in Northern Transylvania and the changes following the award are presented in detail in the next section. The rest of Transylvania, known as Southern Transylvania, with 2,274,600 Romanians and 363,200 Hungarians, remained part of the Kingdom of Romania.

Statistics[]

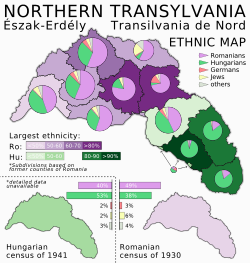

The territory in question covered an area of 43,104 square kilometres (16,643 sq mi), or 43,492 km2 (16,792 sq mi) (depending on the source). The 1930 Romanian census registered for the region a population of 2,393,300. In 1941, the Hungarian authorities conducted a new census, which registered a total population of 2,578,100. Both censuses asked language and nationality separately. The results of both censuses are summarized in this table:

| Nationality/ language |

1930 Romanian census | 1941 Hungarian census | 1940 Romanian estimate[7] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nationality | Language | Nationality | Language | ||

| Hungarian | 912,500 | 1,007,200 | 1,380,500 | 1,344,000 | 968,371 |

| Romanian | 1,176,900 | 1,165,800 | 1,029,000 | 1,068,700 | 1,304,898 |

| German | 68,300 | 59,700 | 44,600 | 47,300 | N/A |

| Jewish/Yiddish | 138,800 | 99,600 | 47,400 | 48,500 | 200,000 |

| Other | 96,800 | 61,000 | 76,600 | 69,600 | N/A |

As Árpád E. Varga wrote, "the census conducted in 1930 met international statistical requirements in every respect. In order to establish nationality, the compilers devised a complex criterion system, unique at the time, which covered citizenship, nationality, native language (i.e. the language spoken in the family) and religion".

Apart from natural population growth, the differences between the censuses were caused by other complex reasons, like migration, the assimilation of Jews and bilingual speakers. According to Hungarian registrations, 100,000 Hungarian refugees had arrived in Hungary from South Transylvania by January 1941. Most of them sought refuge in the north, and almost as many persons arrived from Hungary in the redeemed territories as those who moved to the Trianon Hungarian territory from South Transylvania.

As a result of the migrations, the number of North Transylvanian Hungarians increased by almost 100,000. To compensate, many Romanians were obliged to leave North Transylvania. Some 100,000 had left by February 1941, according to the incomplete registration of North Transylvanian refugees that was carried out by the Romanian government. Also, a fall in the total population suggests that a further 40,000 to 50,000 Romanians moved from North Transylvania to South Transylvania, including refugees who were omitted from the official registration for various reasons.

Hungarian gains by assimilation were balanced by losses for other groups of native speakers, such as Jews. The shift of languages was most typical among bilingual Romanians and Hungarians. On the other hand, in Máramaros and Szatmár Counties, dozens of settlements had many people who had declared themselves as Romanian but now identified themselves as Hungarian, despite not speaking any Hungarian even in 1910.

Aftermath[]

| Redeem of Northern Transylvania | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

Supported by: | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Unknown |

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Unknown |

First Army Second Army | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

Romanian military: Unknown Romanian civilians: Hundreds killed |

Hungarian military: 4 killed (presumably) Several tanks damaged[8] Hungarian civilians: Unknown | ||||||||

The historian Keith Hitchins summarised the situation created by the award in his book "Rumania: 1866-1947 (Oxford History of Modern Europe), Oxford University Press, 1994":

- Far from settling matters, the Vienna Award had exacerbated relations between Romania and Hungary. It did not solve the nationality problem by separating all Magyars from all Romanians. Some 1,150,000 to 1,300,000 Romanians, or 48 per cent to over 50 per cent of the population of the ceded territory, depending upon whose statistics are used, remained north of the new frontier, while about 500,000 Magyars (other Hungarian estimates go as high as 800,000, Romanian as low as 363,000) continued to reside in the south.

Romania had 14 days to evacuate concerned territories and assign them to Hungary. The Hungarian troops stepped across the Trianon borders on 5 September. The Regent of Hungary, Miklós Horthy, also attended in the entry. The troops reached the pre-Trianon border, completing the recovering process, on 13 September.

Generally, the ethnic Hungarian population welcomed the troops and regarded the separation from Romania as a liberation. The large ethnic Romanian community that found itself under the Hungarian occupation had nothing to celebrate, as it considered the Second Vienna Award the return to the long time of Hungarian rule. Upon entering the awarded territory, the Hungarian Army committed massacres against the Romanian population, including the following:

- The Treznea massacre. On 9 September, in the village of Treznea (Hungarian: Ördögkút), some Hungarian troops made a 4 km detour from the Zalău–Cluj route of the Hungarian Army and started firing at will on locals of all ages, killing many of them and partially destroying the Orthodox church. The official Hungarian sources then recorded that 87 Romanians and 6 Jews were killed, including the local Orthodox priest and the Romanian local teacher with his wife, but some Romanian sources give as many as 263 locals who were killed. Some Hungarian historians claim that the killings came in retaliation after the Hungarian troops were fired upon by inhabitants, allegedly incited by the local Romanian Orthodox priest, but the claims are not supported by the accounts of several witnesses. The motivation of the 4 km detour of the Hungarian troops from the rest of the Hungarian Army is still a point of contention, but most evidence points towards the local noble Ferenc Bay, who had lost a large part of his estates to peasants in the 1920s, as most of the violence was directed towards the peasants living on his former estate.

- The Ip massacre. In similar circumstances, 159 local villagers were killed on 13 and 14 September 1940 by Hungarian troops in the village of Ip (Hungarian: Szilágyipp). The commander of the Hungarian troops who perpetrated the massacre of civilians was lieutenant Zoltán Vasváry. On September 14, at the order of Lt. Vasvári, a pit 24 meters long by 4 meters wide was dug in the village cemetery; the corpses of those killed in the massacre were buried head-to-head in two rows, with no religious ceremony.[9]

- The Nușfalău massacre occurred in the village of Nușfalău (Hungarian: Szilágynagyfalu) on 8 September 1940, when a Hungarian soldier with the support of some natives tortured and killed eleven people (two women and nine men) of Romanian ethnicity from a nearby village, who were passing through the area.

The exact number of casualties is disputed among some historians, but the existence of such events cannot be disputed.

The retreat of the Romanian Army was also not free from incidents, mostly damages to infrastructure and destruction of public documents.

Carol II line[]

The Carol II fortified line (Romanian: Linia fortificată Carol al II-lea) had been built in the late 1930s at the order of King Carol II for the purpose of defending Romania's western border. Stretching across 300 kilometres (190 mi), the line itself was not continuous but protected only the most likely routes towards inner Transylvania. It consisted of 320 casemates: 80 built in 1938, 180 built in 1939 and the rest built in the first half of 1940. There was a distance of about 400 m between each casemate, all of which were made of reinforced concrete, of varying sizes but all armed with machine guns. The artillery was placed between the casemates themselves. In front of the casemates, there were rows of barbed wire, mine fields and one large antitank ditch, in some places filled with water. The firing from the casemates was calculated to be very dense and crossed to cause as many losses as possible to the enemy infantry. The role of the fortified line was not to stop incoming attacks but to delay them, inflict as many losses as possible and give time for the bulk of the Romanian Army to be mobilized.

After the Award, the entire line fell in the area allotted to Hungary. The Romanian troops evacuated as much equipment as possible, but the dug-in telephone lines could not be recovered and so were eventually used by the Hungarian Army. The Hungarians also salvaged as much metal as possible, which eventually amounted to a huge amount. After all useful equipment and materiel had been salvaged, the casemates were blown up by the Hungarians to prevent them from being used again.[10]

Nullification[]

The Second Vienna Award was voided by the Allied Commission through the Armistice Agreement with Romania (12 September 1944), whose Article 19 stipulated the following:

- The Allied Governments regard the decision of the Vienna award regarding Transylvania as void and are agreed that Transylvania (the greater part thereof) should be returned to Romania, subject to confirmation at the peace settlement, and the Soviet Government agrees that Soviet forces shall take part for this purpose in joint military operations with Romania against Germany and Hungary.

That came after King Michael's Coup of 23 August 1944, when Romania changed sides and joined the Allies. Thereafter, the Romanian Army fought Nazi Germany and its allies, first in Romania and later in German-occupied Hungary and Slovakia, such as during the Budapest Offensive, the Siege of Budapest, the Bratislava–Brno Offensive, and the Prague Offensive. After the Battle of Carei on 25 October 1944, all the territory of Northern Transylvania was under the control of Romanian and Soviet troops. The Soviet Union kept administrative control until 9 March 1945, when Northern Transylvania reverted to Romania.

The 1947 Paris Peace Treaties reaffirmed the borders between Romania and Hungary, as they had been originally defined in the Treaty of Trianon, 27 years earlier.

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Cathlan 2010, p. 1141.

- ^ , Transylvania's History at Kulturális Innovációs Alapítvány

- ^ Shirer 1960, p. 800.

- ^ Giurescu 2000, pp. 35–37.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Giurescu 2000, pp. 37–39.

- ^ Dan-Străulești, Petre (2017). Atlas istoric ilustrat al României [Illustrated historical atlas of Romania]. Bucharest: Editura Litera. p. 86. ISBN 9786063319006.

- ^ Keith Hitchins, Rumania: 1866-1947, Oxford University Press, 1994, p. 486

- ^ Hungarian armor http://ftr.wot-news.com/2013/11/16/hungarian-armor-part-4-toldi-ii-toldi-iia-toldi-iii/

- ^ Lechințan, V. "Procesul criminalilor de război de la Ip, Treznea, Huedin, Mureșenii de Câmpie și din alte localități sălăjene" [The Trial of the War Criminals from Ip, Treznea, Huedin, Mureșenii de Câmpie and other localities from Sălaj County] (PDF) (in Romanian). pp. 278, 280, 293. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ "Linia fortificată Carol al II-lea" [The Carol II fortified line] (in Romanian). Retrieved May 24, 2020.

Sources[]

- Árpád E. Varga. Erdély magyar népessége 1870-1995 között. Magyar Kisebbség 3–4, 1998, pp. 331–407.

- Bodea, Gheorghe I.; Suciu, Vasile T.; Pușcaș, Ilie I. (1988). Administrația militară horthystă în nord-vestul României. Cluj-Napoca: Editura Dacia. OCLC 1036519807.

- Bucur, Maria (April 1, 2002). "Treznea: Trauma, nationalism and the memory of World War II in Romania". Rethinking History. 6 (1): 35–55. doi:10.1080/13642520110112100.

- Giurescu, Dinu C. (2000). Romania in the Second World War (1939–1945). East European Monographs. Boulder, CO; New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780880334433. OCLC 1170535723.

- Țurlea, Petre (1996). Ip și Trăznea: Atrocități maghiare și acțiune diplomatică (in Romanian). București: Editura Enciclopedică. ISBN 9789734501816. OCLC 243869011.

- Alessandro Vagnini. German-Italian Commissions in Transylvania 1940-1943. A crucial key Study for Italian Diplomacy, Studia Universitatis Petru Maior, Historia Volume 9, 2009, pp. 165–187.

- Shirer, William (1960). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-4259-9. OCLC 22888118.

- Nolan, Cathal J. (2010). The Concise Encyclopedia of World War II [2 volumes]. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33050-6. OCLC 1037383584.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Second Vienna Award. |

- Text of the Second Vienna Award

- , Essays on Transylvania's Demographic History. (Mainly in Hungarian, but also in English and Romanian.)

- (in Russian) Проблема Tрансильвании в отношениях СССР с союзниками по антигитлеровской коалиции (июнь 1941 г. — май 1945 г.) (an article on the Allies and the question of Transylvania)

- Romania in World War II

- History of Cluj-Napoca

- Territorial disputes of Romania

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Hungary (1920–1946)

- Territorial disputes of Hungary

- 1940 in Europe

- Arbitration cases

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Romania

- 1940s in Vienna

- Austria–Romania relations

- Hungary–Romania relations

- Territorial evolution of Hungary

- August 1940 events

- 1940 in Hungary

- August 1940 events in Romania

- Treaties concluded in 1940

- Treaties involving territorial changes

- Territorial evolution of Romania

- Germany–Romania relations

- Germany–Hungary relations

- Foreign relations of Nazi Germany