Spanish conquest of the Maya

The Spanish conquest of the Maya was a protracted conflict during the Spanish colonisation of the Americas, in which the Spanish conquistadores and their allies gradually incorporated the territory of the Late Postclassic Maya states and polities into the colonial Viceroyalty of New Spain. The Maya occupied a territory that is now incorporated into the modern countries of Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras and El Salvador; the conquest began in the early 16th century and is generally considered to have ended in 1697.

Before the conquest, Maya territory contained a number of competing kingdoms. Many conquistadors viewed the Maya as infidels who needed to be forcefully converted and pacified, despite the achievements of their civilization.[2] The first contact between the Maya and European explorers came in 1502, during the fourth voyage of Christopher Columbus, when his brother Bartholomew encountered a canoe. Several Spanish expeditions followed in 1517 and 1519, making landfall on various parts of the Yucatán coast. The Spanish conquest of the Maya was a prolonged affair; the Maya kingdoms resisted integration into the Spanish Empire with such tenacity that their defeat took almost two centuries.[3] The Itza Maya and other lowland groups in the Petén Basin were first contacted by Hernán Cortés in 1525, but remained independent and hostile to the encroaching Spanish until 1697, when a concerted Spanish assault led by Martín de Urzúa y Arizmendi finally defeated the last independent Maya kingdom.

The conquest of the Maya was hindered by their politically fragmented state. Spanish and native tactics and technology differed greatly. The Spanish engaged in a strategy of concentrating native populations in newly founded colonial towns; they viewed the taking of prisoners as a hindrance to outright victory, whereas the Maya prioritised the capture of live prisoners and of booty. Among the Maya, ambush was a favoured tactic; in response to the use of Spanish cavalry, the highland Maya took to digging pits and lining them with wooden stakes. Native resistance to the new nucleated settlements took the form of the flight into inaccessible regions such as the forest or joining neighbouring Maya groups that had not yet submitted to the European conquerors. Spanish weaponry included broadswords, rapiers, lances, pikes, halberds, crossbows, matchlocks and light artillery. Maya warriors fought with flint-tipped spears, bows and arrows, stones, and wooden swords with inset obsidian blades, and wore padded cotton armour to protect themselves. The Maya lacked key elements of Old World technology such as a functional wheel, horses, iron, steel, and gunpowder; they were also extremely susceptible to Old World diseases, against which they had no resistance.

Geography[]

The Maya civilization occupied a wide territory that included southeastern Mexico and northern Central America; this area included the entire Yucatán Peninsula, and all of the territory now incorporated into the modern countries of Guatemala and Belize, as well as the western portions of Honduras and El Salvador.[4] In Mexico, the Maya occupied territory now incorporated into the states of Chiapas, Tabasco, Campeche, Quintana Roo and Yucatán.[5]

The Yucatán Peninsula is bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the east and by the Gulf of Mexico to the north and west. It incorporates the modern Mexican states of Yucatán, Quintana Roo and Campeche, the eastern portion of the state of Tabasco, most of the Guatemalan department of Petén, and all of Belize.[6] Most of the peninsula is formed by a vast plain with few hills or mountains and a generally low coastline. The northwestern and northern portions of the Yucatán Peninsula experience lower rainfall than the rest of the peninsula; these regions feature highly porous limestone bedrock resulting in less surface water.[7] In contrast, the northeastern portion of the peninsula is characterised by forested swamplands.[7] The northern portion of the peninsula lacks rivers, except for the Champotón River – all other rivers are located in the south.[8]

The Petén region consists of densely forested low-lying limestone plain, [9] crossed by low east–west oriented ridges and is characterised by a variety of forest and soil types; water sources include generally small rivers and low-lying seasonal swamps known as bajos.[10] A chain of fourteen lakes runs across the central drainage basin of Petén.[11] The largest lake is Lake Petén Itza; it measures 32 by 5 kilometres (19.9 by 3.1 mi). A broad savannah extends south of the central lakes. To the north of the lakes region bajos become more frequent, interspersed with forest.[12] To the south the plain gradually rises towards the Guatemalan Highlands.[13] Dense forest covers northern Petén and Belize, most of Quintana Roo, southern Campeche and a portion of the south of Yucatán state. Further north, the vegetation turns to lower forest consisting of dense scrub.[14]

Chiapas occupies the extreme southeast of Mexico; it possesses 260 kilometres (160 mi) of Pacific coastline.[15] Chiapas features two principal highland regions; to the south is the Sierra Madre de Chiapas and in central Chiapas are the (Central Highlands). They are separated by the Depresión Central, containing the drainage basin of the Grijalva River, featuring a hot climate with moderate rainfall.[16] The Sierra Madre highlands gain altitude from west to east, with the highest mountains near the Guatemalan border.[17] The Central Highlands of Chiapas rise sharply to the north of the Grijalva, to a maximum altitude of 2,400 metres (7,900 ft), then descend gradually towards the Yucatán Peninsula. They are cut by deep valleys running parallel to the Pacific coast, and feature a complex drainage system that feeds both the Grijalva and the Lacantún River.[18] At the eastern end of the Central Highlands is the Lacandon Forest, this region is largely mountainous with lowland tropical plains at its easternmost extreme.[19] The littoral zone of Soconusco lies to the south of the Sierra Madre de Chiapas,[20] and consists of a narrow coastal plain and the foothills of the Sierra Madre.[21]

Maya region before the conquest[]

The Maya had never been unified as a single empire, but by the time the Spanish arrived Maya civilization was thousands of years old and had already seen the rise and fall of great cities.[22]

Yucatán[]

The first large Maya cities developed in the Petén Basin in the far south of the Yucatán Peninsula as far back as the Middle Preclassic (c. 600–350 BC),[23] and Petén formed the heartland of the ancient Maya civilization during the Classic period (c. AD 250–900).[24] The 16th-century Maya provinces of northern Yucatán are likely to have evolved out of polities of the Maya Classic period.[25] The great cities that dominated Petén had fallen into ruin by the beginning of the 10th century with the onset of the Classic Maya collapse.[26] A significant Maya presence remained in Petén into the Postclassic period after the abandonment of the major Classic period cities; the population was particularly concentrated near permanent water sources.[27]

In the early 16th century, the Yucatán Peninsula was still dominated by the Maya civilization. It was divided into a number of independent provinces that shared a common culture but varied in their internal sociopolitical organisation.[25] When the Spanish discovered Yucatán, the provinces of Mani and Sotuta were two of the most important polities in the region. They were mutually hostile; the of Mani allied themselves with the Spanish, while the Cocom Maya of Sotuta became the implacable enemies of the European colonisers.[28]

At the time of conquest, polities in the northern Yucatán peninsula included Mani, Cehpech and Chakan;[25] further east along the north coast were Ah Kin Chel, Cupul, and Chikinchel.[29] , Uaymil, Chetumal all bordered on the Caribbean Sea. Cochuah was also in the eastern half of the peninsula. Tases, and Sotuta were all landlocked provinces. Chanputun (modern Champotón) was on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, as was Acalan.[29] In the southern portion of the peninsula, a number of polities occupied the Petén Basin.[23] The Kejache occupied a territory between the Petén lakes and what is now Campeche. The Cholan Maya-speaking Lakandon (not to be confused with the modern inhabitants of Chiapas by that name) controlled territory along the tributaries of the Usumacinta River spanning eastern Chiapas and southwestern Petén.[30] The Lakandon had a fierce reputation amongst the Spanish.[31]

Before their defeat in 1697 the Itza controlled or influenced much of Petén and parts of Belize. The Itza were warlike, and their capital was Nojpetén, an island city upon Lake Petén Itzá.[30] The Kowoj were the second in importance; they were hostile towards their Itza neighbours. The Kowoj were located around the eastern Petén lakes.[32] The Yalain occupied a territory that extended eastwards to Tipuj in Belize.[33] Other groups in Petén are less well known, and their precise territorial extent and political makeup remains obscure; among them were the Chinamita, the Icaiche, the Kejache, the Lakandon Chʼol, the Manche Chʼol, and the Mopan.[34]

Maya Highlands[]

What is now the Mexican state of Chiapas was divided roughly equally between the non-Maya Zoque in the western half and Maya in the eastern half; this distribution continued up to the time of the Spanish conquest.[35] On the eve of the conquest the highlands of Guatemala were dominated by several powerful Maya states.[36] In the centuries preceding the arrival of the Spanish the Kʼicheʼ had carved out a small empire covering a large part of the western Guatemalan Highlands and the neighbouring Pacific coastal plain. However, in the late 15th century the Kaqchikel rebelled against their former Kʼicheʼ allies and founded a new kingdom to the southeast with Iximche as its capital. In the decades before the Spanish invasion the Kaqchikel kingdom had been steadily eroding the kingdom of the Kʼicheʼ.[37] Other highland groups included the Tzʼutujil around Lake Atitlán, the Mam in the western highlands and the Poqomam in the eastern highlands.[38] The central highlands of Chiapas were occupied by a number of Maya peoples,[39] including the Tzotzil, who were divided into a number of provinces; the province of Chamula was said to have five small towns grouped closely together.[40] The Tojolabal held territory around Comitán.[41] The Maya held territory in the upper reaches of the Grijalva drainage, near the Guatemalan border,[42] and were probably a subgroup of the Tojolabal.[43]

Pacific lowlands[]

Soconusco was an important communication route between the central Mexican highlands and Central America. It had been subjugated by the Aztec Triple Alliance at the end of the 15th century, under the emperor Ahuizotl,[44] and paid tribute in cacao.[21] The highland Kʼicheʼ dominated the Pacific coastal plain of western Guatemala.[37] The eastern portion of the Pacific plain was occupied by the non-Maya Pipil and Xinca.[45]

Background to the conquest[]

Christopher Columbus discovered the New World for the Kingdom of Castile and Leon in 1492. Private adventurers thereafter entered into contracts with the Spanish Crown to conquer the newly discovered lands in return for tax revenues and the power to rule.[46] In the first decades after the discovery of the new lands, the Spanish colonised the Caribbean and established a centre of operations on the island of Cuba.[47] By August 1521 the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan had fallen to the Spanish.[48] Within three years of the fall of Tenochtitlan the Spanish had conquered a large part of Mexico, extending as far south as the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. The newly conquered territory became New Spain, headed by a viceroy who answered to the king of Spain via the Council of the Indies.[49]

Weaponry, strategies and tactics[]

The conquistadors were all volunteers, the majority of whom did not receive a fixed salary but instead a portion of the spoils of victory, in the form of precious metals, land grants and provision of native labour.[52] Many of the Spanish were already experienced soldiers who had previously campaigned in Europe.[53] In addition to Spaniards, the invasion force probably included dozens of armed African slaves and freemen.[54] The politically fragmented state of the Yucatán Peninsula at the time of conquest hindered the Spanish invasion, since there was no central political authority to be overthrown. However, the Spanish exploited this fragmentation by taking advantage of pre-existing rivalries between polities.[25] Among Mesoamerican peoples the capture of prisoners was a priority, while to the Spanish such taking of prisoners was a hindrance to outright victory.[55] The Spanish engaged in a strategy of concentrating native populations in newly founded colonial towns, or reducciones (also known as congregaciones).[56] Native resistance to the new nucleated settlements took the form of the flight of the indigenous inhabitants into inaccessible regions such as the forest or joining neighbouring Maya groups that had not yet submitted to the Spanish.[57] Those that remained behind in the reducciones often fell victim to contagious diseases;[58] coastal reducciones, while convenient for Spanish administration, were also vulnerable to pirate attacks.[59]

Spanish weapons and tactics[]

Spanish weaponry and tactics differed greatly from that of the indigenous peoples. This included the Spanish use of crossbows, firearms (including muskets, arquebuses and cannon),[60] war dogs and war horses.[55] Horses had never been encountered by the Maya before,[61] and their use gave the mounted conquistador an overwhelming advantage over his unmounted opponent, allowing the rider to strike with greater force while simultaneously making him less vulnerable to attack. The mounted conquistador was highly manoeuvrable and this allowed groups of combatants to quickly displace themselves across the battlefield. The horse itself was not passive, and could buffet the enemy combatant.[62]

The crossbows and early firearms were unwieldy and deteriorated rapidly in the field, often becoming unusable after a few weeks of campaigning due to the effects of the climate.[63] The Maya lacked key elements of Old World technology, such as the use of iron and steel and functional wheels.[64] The use of steel swords was perhaps the greatest technological advantage held by the Spanish, although the deployment of cavalry helped them to rout indigenous armies on occasion.[65] The Spanish were sufficiently impressed by the quilted cotton armour of their Maya enemies that they adopted it in preference to their own steel armour.[66] The conquistadors applied a more effective military organisation and strategic awareness than their opponents, allowing them to deploy troops and supplies in a way that increased the Spanish advantage.[67]

The 16th-century Spanish conquistadors were armed with one- and two-handed broadswords, lances, pikes, rapiers, halberds, crossbows, matchlocks and light artillery.[68] Crossbows were easier to maintain than matchlocks, especially in the humid tropical climate of the Caribbean region that included much of the Yucatán Peninsula.[69]

In Guatemala the Spanish routinely fielded indigenous allies; at first these were Nahua brought from the recently conquered Mexico, later they also included Maya. It is estimated that for every Spaniard on the field of battle, there were at least 10 native auxiliaries. Sometimes there were as many as 30 indigenous warriors for every Spaniard, and the participation of these Mesoamerican allies was decisive.[70]

Native weapons and tactics[]

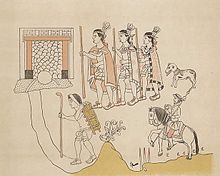

Maya armies were highly disciplined, and warriors participated in regular training exercises and drills; every able-bodied adult male was available for military service. Maya states did not maintain standing armies; warriors were mustered by local officials who reported back to appointed warleaders. There were also units of full-time mercenaries who followed permanent leaders.[71] Most warriors were not full-time, however, and were primarily farmers; the needs of their crops usually came before warfare.[72] Maya warfare was not so much aimed at destruction of the enemy as the seizure of captives and plunder.[73] Maya warriors entered battle against the Spanish with flint-tipped spears, bows and arrows and stones. They wore padded cotton armour to protect themselves.[74] The Spanish described the weapons of war of the Petén Maya as bows and arrows, fire-sharpened poles, flint-headed spears and two-handed swords crafted from strong wood with the blade fashioned from inset obsidian,[75] similar to the Aztec macuahuitl. Maya warriors wore body armour in the form of quilted cotton that had been soaked in salt water to toughen it; the resulting armour compared favourably to the steel armour worn by the Spanish.[66] Warriors bore wooden or animal hide shields decorated with feathers and animal skins.[72] The Maya had historically employed ambush and raiding as their preferred tactic, and its employment against the Spanish proved troublesome for the Europeans.[66] In response to the use of cavalry, the highland Maya took to digging pits on the roads, lining them with fire-hardened stakes and camouflaging them with grass and weeds, a tactic that according to the Kaqchikel killed many horses.[76]

Impact of Old World diseases[]

Epidemics incidentally introduced by the Spanish included smallpox, measles and influenza. These diseases, together with typhus and yellow fever, had a major impact on Maya populations.[77] The Old World diseases brought with the Spanish and against which the indigenous New World peoples had no resistance were a deciding factor in the conquest; they decimated populations before battles were even fought.[78] It is estimated that 90% of the indigenous population had been eliminated by disease within the first century of European contact.[79]

A single soldier arriving in Mexico in 1520 was carrying smallpox and initiated the devastating plagues that swept through the native populations of the Americas.[80] Modern estimates of native population decline vary from 75% to 90% mortality. Maya written histories suggest that smallpox was rapidly transmitted throughout the Maya area the same year that it arrived in central Mexico. Among the most deadly diseases were the aforementioned smallpox, influenza, measles and a number of pulmonary diseases, including tuberculosis.[81] Modern knowledge of the impact of these diseases on populations with no prior exposure suggests that 33–50% of the population of the Maya highlands perished.[82]

These diseases swept through Yucatán in the 1520s and 1530s, with periodic recurrences throughout the 16th century. By the late 16th century, malaria had arrived in the region, and yellow fever was first reported in the mid-17th century. Mortality was high, with approximately 50% of the population of some Yucatec Maya settlements being wiped out.[81] Those areas of the peninsula that experience damper conditions became rapidly depopulated after the conquest with the introduction of malaria and other waterborne parasites.[7] The native population of the northeastern portion of the peninsula was almost completely eliminated within fifty years of the conquest.[59] Soconusco also suffered catastrophic population collapse, with an estimated 90–95% drop.[83]

In the south, conditions conducive to the spread of malaria existed throughout Petén and Belize.[59] In Tabasco the population of approximately 30,000 was reduced by an estimated 90%, with measles, smallpox, catarrhs, dysentery and fevers being the main culprits.[59] At the time of the fall of Nojpetén in 1697, there are estimated to have been 60,000 Maya living around Lake Petén Itzá, including a large number of refugees from other areas. It is estimated that 88% of them died during the first ten years of colonial rule owing to a combination of disease and war.[84]

First encounters: 1502 and 1511[]

On 30 July 1502, during his fourth voyage, Christopher Columbus arrived at Guanaja, one of the Bay Islands off the coast of Honduras. He sent his brother Bartholomew to scout the island. As Bartholomew explored, a large trading canoe approached. Bartholomew Columbus boarded the canoe, and found it was a Maya trading vessel from Yucatán, carrying well-dressed Maya and a rich cargo.[85] The Europeans looted whatever took their interest from amongst the cargo and seized the elderly captain to serve as an interpreter; the canoe was then allowed to continue on its way.[86] This was the first recorded contact between Europeans and the Maya.[87] It is likely that news of the piratical strangers in the Caribbean passed along the Maya trade routes – the first prophecies of bearded invaders sent by Kukulkan, the northern Maya feathered serpent god, were probably recorded around this time, and in due course passed into the books of Chilam Balam.[88]

In 1511 the Spanish caravel Santa María de la Barca sailed along the Central American coast under the command of . The ship foundered upon a reef somewhere off Jamaica.[89] There were just twenty survivors from the wreck, including Captain Valdivia, Gerónimo de Aguilar and Gonzalo Guerrero.[90] They set themselves adrift in one of the ship's boats and after thirteen days, during which half of the survivors died, they made landfall upon the coast of Yucatán.[89] There they were seized by a Halach Uinik, a Maya lord. Captain Vildivia was sacrificed with four of his companions, and their flesh was served at a feast. Aguilar and Guerrero were held prisoner and fattened for killing, together with five or six of their shipmates. Aguilar and Guerrero managed to escape their captors and fled to a neighbouring lord, who took them prisoner and kept them as slaves. After a time, Gonzalo Guerrero was passed as a slave to the lord Nachan Can of Chetumal. Guerrero became completely Mayanised and by 1514 Guerrero had achieved the rank of nacom, a war leader who served against Nachan Can's enemies.[91]

Exploration of the Yucatán coast, 1517–1519[]

Francisco Hernández de Córdoba, 1517[]

In 1517, Francisco Hernández de Córdoba set sail from Cuba with a small fleet.[92] The expedition sailed west from Cuba for three weeks before sighting the northeastern tip of the Yucatán Peninsula. The ships could not put in close to the shore due to the coastal shallows. However, they could see a Maya city some two leagues inland. The following morning, ten large canoes rowed out to meet the Spanish ships, and over thirty Maya boarded the vessels and mixed freely with the Spaniards.[93] The following day the conquistadors put ashore. As the Spanish party advanced along a path towards the city, they were ambushed by Maya warriors. Thirteen Spaniards were injured by arrows in the first assault, but the conquistadors regrouped and repulsed the Maya attack. They advanced to a small plaza upon the outskirts of the city.[74] When the Spaniards ransacked nearby temples they found a number of low-grade gold items, which filled them with enthusiasm. The expedition captured two Mayas to be used as interpreters and retreated to the ships. The Spanish discovered that the Maya arrowheads were fashioned from flint and tended to shatter on impact, causing infected wounds and a slow death; two of the wounded Spaniards died from the arrow-wounds inflicted in the ambush.[94]

Over the next fifteen days the fleet followed the coastline west, and then south.[94] The expedition was now perilously short of fresh water, and shore parties searching for water were left dangerously exposed because the ships could not pull close to the shore due to the shallows.[95] On 23 February 1517,[96] the Spanish spotted the Maya city of Campeche. A large contingent put ashore to fill their water casks. They were approached by about fifty finely dressed and unarmed Indians while the water was being loaded into the boats; they questioned the Spaniards as to their purpose by means of signs. The Spanish party then accepted an invitation to enter the city.[97] Once inside the city, the Maya leaders made it clear that the Spanish would be killed if they did not withdraw immediately. The Spanish party retreated in defensive formation to the safety of the ships.[98]

After ten more days, the ships spotted an inlet close to Champotón, and a landing party discovered fresh water.[99] Armed Maya warriors approached from the city, and communication was attempted with signs. Night fell by the time the water casks had been filled and the attempts at communication concluded. By sunrise the Spanish had been surrounded by a sizeable army. The massed Maya warriors launched an assault and all of the Spanish party received wounds in the frantic melee that followed, including Hernández de Córdoba. The Spanish regrouped and forced passage to the shore, where their discipline collapsed and a frantic scramble for the boats ensued, leaving the Spanish vulnerable to the pursuing Maya warriors who waded into the sea behind them. By the end of the battle, the Spanish had lost over fifty men, more than half their number,[100] and five more men died from their wounds in the following days.[101] The battle had lasted only an hour. They were now far from help and low on supplies; too many men had been lost and injured to sail all three ships back to Cuba, so one was abandoned.[102] The ship's pilot then steered a course for Cuba via Florida, and Hernández de Cordóba wrote a report to Governor Diego Velázquez describing the voyage and, most importantly, the discovery of gold. Hernández died soon after from his wounds.[103]

Juan de Grijalva, 1518[]

Diego Velázquez, the governor of Cuba, was enthused by Hernández de Córdoba's report of gold in Yucatán.[96] He organised a new expedition and placed his nephew Juan de Grijalva in command over his four ships.[104] The small fleet left Cuba in April 1518,[105] and made its first landfall upon the island of Cozumel,[106] off the east coast of Yucatán.[105] The Maya inhabitants of Cozumel fled the Spanish and would not respond to Grijalva's friendly overtures. The fleet then sailed south along the east coast of the peninsula. The Spanish spotted three large Maya cities along the coast, but Grijalva did not land at any of these and turned back north to loop around the north of the peninsula and sail down the west coast.[107] At Campeche the Spanish tried to barter for water but the Maya refused, so Grijalva opened fire against the city with small cannon; the inhabitants fled, allowing the Spanish to take the abandoned city. Messages were sent with a few Maya who had been too slow to escape but the Maya remained hidden in the forest; the Spanish boarded their ships and continued along the coast.[106]

At Champotón, the fleet was approached by a small number of large war canoes, but the ships' cannon soon put them to flight.[106] At the mouth of the Tabasco River the Spanish sighted massed warriors and canoes but the natives did not approach.[108] By means of interpreters, Grijalva indicated that he wished to trade and bartered wine and beads in exchange for food and other supplies. From the natives they received a few gold trinkets and news of the riches of the Aztec Empire to the west. The expedition continued far enough to confirm the reality of the gold-rich empire,[109] sailing as far north as Pánuco River. As the fleet returned to Cuba, the Spanish attacked Champotón to avenge the previous year's defeat of the Spanish expedition led by Hernández. One Spaniard was killed and fifty were wounded in the ensuing battle, including Grijalva. Grijalva put into Havana five months after he had left.[105]

Hernán Cortés, 1519[]

Grijalva's return aroused great interest in Cuba, and Yucatán was believed to be a land of riches waiting to be plundered. A new expedition was organised, with a fleet of eleven ships carrying 500 men and some horses. Hernán Cortés was placed in command, and his crew included officers that would become famous conquistadors, including Pedro de Alvarado, Cristóbal de Olid, Gonzalo de Sandoval and Diego de Ordaz. Also aboard were Francisco de Montejo and Bernal Díaz del Castillo, veterans of the Grijalva expedition.[105]

The fleet made its first landfall at Cozumel; Maya temples were cast down and a Christian cross was put up on one of them.[105] At Cozumel Cortés heard rumours of bearded men on the Yucatán mainland, who he presumed were Europeans.[110] Cortés sent out messengers to them and was able to rescue the shipwrecked Gerónimo de Aguilar, who had been enslaved by a Maya lord. Aguilar had learnt the Yucatec Maya language and became Cortés' interpreter.[111]

From Cozumel, the fleet looped around the north of the Yucatán Peninsula and followed the coast to the Grijalva River, which Cortés named in honour of the Spanish captain who had discovered it.[112] In Tabasco, Cortés anchored his ships at Potonchán,[113] a Chontal Maya town.[114] The Maya prepared for battle but the Spanish horses and firearms quickly decided the outcome. The defeated Chontal Maya lords offered gold, food, clothing and a group of young women in tribute to the victors.[113] Among these women was a young Maya noblewoman called Malintzin,[113] who was given the Spanish name Marina. She spoke Maya and Nahuatl and became the means by which Cortés was able to communicate with the Aztecs.[112] From Tabasco, Cortés continued along the coast, and went on to conquer the Aztecs.[115]

Preparations for conquest of the Highlands, 1522–1523[]

After the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan fell to the Spanish in 1521, the Kaqchikel Maya of Iximche sent envoys to Hernán Cortés to declare their allegiance to the new ruler of Mexico, and the Kʼicheʼ Maya of Qʼumarkaj may also have sent a delegation.[116] In 1522 Cortés sent Mexican allies to scout the Soconusco region of lowland Chiapas, where they met new delegations from Iximche and Qʼumarkaj at Tuxpán;[117] both of the powerful highland Maya kingdoms declared their loyalty to the King of Spain.[116] But Cortés' allies in Soconusco soon informed him that the Kʼicheʼ and the Kaqchikel were not loyal, and were harassing Spain's allies in the region. Cortés despatched Pedro de Alvarado with 180 cavalry, 300 infantry, 4 cannons, and thousands of allied warriors from central Mexico;[118] they arrived in Soconusco in 1523.[116]

Soconusco, 1523–1524[]

Pedro de Alvarado passed through Soconusco with a sizeable force in 1523, en route to conquer Guatemala.[116] Alvarado's army included hardened veterans of the conquest of the Aztecs, and included cavalry and artillery;[119] he was accompanied by a great many indigenous allies.[120] Alvarado was received in peace in Soconusco, and the inhabitants swore allegiance to the Spanish Crown. They reported that neighbouring groups in Guatemala were attacking them because of their friendly outlook towards the Spanish.[121] By 1524, Soconusco had been completely pacified by Alvarado and his forces.[122] Due to the economic importance of cacao to the new colony, the Spanish were reluctant to move the indigenous inhabitants far from their established cacao orchards. As a result, the inhabitants of Soconusco were less likely to be rounded up into new reducción settlements than elsewhere in Chiapas, since the planting of a new cacao crop would have required five years to mature.[123]

Hernán Cortés in the Maya lowlands, 1524–25[]

In 1524,[112] after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, Hernán Cortés led an expedition to Honduras over land, cutting across Acalan in southern Campeche and the Itza kingdom in what is now the northern Petén Department of Guatemala.[124] His aim was to subdue the rebellious Cristóbal de Olid, whom he had sent to conquer Honduras, and who had set himself up independently in that territory.[112] Cortés left Tenochtitlan on 12 October 1524 with 140 Spanish soldiers, 93 of them mounted, 3,000 Mexican warriors, 150 horses, artillery, munitions and other supplies. Cortés marched into Maya territory in Tabasco; the army crossed the Usumacinta River near Tenosique and crossed into the Chontal Maya province of Acalan, where he recruited 600 Chontal Maya carriers. Cortés and his army left Acalan on 5 March 1525.[125]

The expedition passed onwards through Kejache territory,[126] and arrived at the north shore of Lake Petén Itzá on 13 March 1525.[125] The Roman Catholic priests accompanying the expedition celebrated mass in the presence of the king of the Itza, who was said to be so impressed that he pledged to worship the cross and to destroy his idols.[127] Cortés accepted an invitation from Kan Ekʼ to visit Nojpetén.[128] On his departure, Cortés left behind a cross and a lame horse that the Itza treated as a deity, but the animal soon died.[129]

From the lake, Cortés continued on the arduous journey south along the western slopes of the Maya Mountains, during which he lost most of his horses. The expedition became lost in the hills north of Lake Izabal and came close to starvation before they captured a Maya boy who led them to safety.[127] Cortés found a village on the shore of Lake Izabal, and crossed the Dulce River to the settlement of Nito, somewhere on the Amatique Bay,[130] with about a dozen companions, and waited there for the rest of his army to regroup over the next week.[127] By this time the remnants of the expedition had been reduced to a few hundred; Cortés succeeded in contacting the Spaniards he was searching for, only to find that Cristóbal de Olid's own officers had already put down his rebellion. Cortés then returned to Mexico by sea.[131]

Fringes of empire: Belize, 16th–17th centuries[]

No Spanish military expeditions were launched against the Maya of Belize, although both Dominican and Franciscan friars penetrated the region in attempts at evangelising the natives. The only Spanish settlement in the territory was established by Alonso d'Avila in 1531 and lasted less than two years.[132] In 1574, fifty households of Manche Chʼol were relocated from Campin and Yaxal, in southern Belize, to the shore of Lake Izabal, but they soon fled back into the forest.[133] In order to counter Spanish encroachment into their territory, the local Maya maintained a tense alliance with English loggers operating in central Belize.[134] In 1641, the Franciscans established two reducciones among the Muzul Maya of central Belize, at Zoite and Cehake; both settlements were sacked by Dutch corsairs within a year.[135]

Conquest of the Maya Highlands, 1524–1526[]

Subjugation of the Kʼicheʼ, 1524[]

... we waited until they came close enough to shoot their arrows, and then we smashed into them; as they had never seen horses, they grew very fearful, and we made a good advance ... and many of them died.

Pedro de Alvarado describing the approach to Quetzaltenango in his 3rd letter to Hernán Cortés[136]

Pedro de Alvarado and his army advanced along the Pacific coast unopposed until they reached the Samalá River in western Guatemala. This region formed a part of the Kʼicheʼ kingdom, and a Kʼicheʼ army tried unsuccessfully to prevent the Spanish from crossing the river. Once across, the conquistadors ransacked nearby settlements.[137] On 8 February 1524 Alvarado's army fought a battle at Xetulul, (modern San Francisco Zapotitlán). The Spanish and their allies stormed the town and set up camp in the marketplace.[138] Alvarado then headed upriver into the Sierra Madre mountains towards the Kʼicheʼ heartlands, crossing the pass into the valley of Quetzaltenango. On 12 February 1524 Alvarado's Mexican allies were ambushed in the pass and driven back by Kʼicheʼ warriors but a Spanish cavalry charge scattered the Kʼicheʼ and the army crossed to the city of Xelaju (modern Quetzaltenango) to find it deserted.[139] The Spanish accounts relate that at least one and possibly two of the ruling lords of Qʼumarkaj died in the fierce battles upon the initial approach to Quetzaltenango.[140] Almost a week later, on 18 February 1524,[141] a 30,000-strong Kʼicheʼ army confronted the Spanish army in the Quetzaltenango valley and was comprehensively defeated; many Kʼicheʼ nobles were among the dead.[142] This battle exhausted the Kʼicheʼ militarily and they asked for peace, and invited Pedro de Alvarado into their capital Qʼumarkaj. Alvarado was deeply suspicious of Kʼicheʼ intentions but accepted the offer and marched to Qʼumarkaj with his army.[143] At Tzakahá the Spanish conducted a Roman Catholic mass under a makeshift roof;[144] this site was chosen to build the first church in Guatemala. The first Easter mass held in Guatemala was celebrated in the new church, during which high-ranking natives were baptised.[145]

In March 1524 Pedro de Alvarado camped outside Qʼumarkaj.[146] He invited the Kʼicheʼ lords Oxib-Keh (the ajpop, or king) and Beleheb-Tzy (the ajpop kʼamha, or king elect) to visit him in his camp.[147] As soon as they did so, he seized them as prisoners. In response to a furious Kʼicheʼ counterattack, Alvarado had the captured Kʼicheʼ lords burnt to death, and then proceeded to burn the entire city.[148] After the destruction of Qʼumarkaj, Pedro de Alvarado sent messages to Iximche, capital of the Kaqchikel, proposing an alliance against the remaining Kʼicheʼ resistance. Alvarado wrote that they sent 4000 warriors to assist him, although the Kaqchikel recorded that they sent only 400.[143] With the capitulation of the Kʼicheʼ kingdom, various non-Kʼicheʼ peoples under Kʼicheʼ dominion also submitted to the Spanish. This included the Mam inhabitants of the area now within the modern department of San Marcos.[149]

Kaqchikel alliance and conquest of the Tzʼutujil, 1524[]

On 14 April 1524, the Spanish were invited into Iximche and were well received by the lords Belehe Qat and Cahi Imox.[150][nb 2] The Kaqchikel kings provided native soldiers to assist the conquistadors against continuing Kʼicheʼ resistance and to help with the defeat of the neighbouring Tzʼutujil kingdom.[152] The Spanish only stayed briefly before continuing to Atitlan and the Pacific coast. The Spanish returned to the Kaqchikel capital on 23 July 1524 and on 27 July Pedro de Alvarado declared Iximche as the first capital of Guatemala, Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala ("St. James of the Knights of Guatemala").[153]

After two Kaqchikel messengers sent by Pedro de Alvarado were killed by the Tzʼutujil,[154] the conquistadors and their Kaqchikel allies marched against the Tzʼutujil.[143] Pedro de Alvarado led 60 cavalry, 150 Spanish infantry and an unspecified number of Kaqchikel warriors. The Spanish and their allies arrived at the lakeshore after a day's march, and Alvarado rode ahead with 30 cavalry along the lake shore until he engaged a hostile Tzʼutujil force, which was broken by the Spanish charge.[155] The survivors were pursued across a causeway to an island on foot before the inhabitants could break the bridges.[156] The rest of Alvarado's army soon arrived and they successfully stormed the island. The surviving Tzʼutujil fled into the lake and swam to safety. The Spanish could not pursue them because 300 canoes sent by the Kaqchikels had not yet arrived. This battle took place on 18 April.[157]

The following day the Spanish entered Tecpan Atitlan, the Tzʼutujil capital, but found it deserted. The Tzʼutujil leaders responded to Alvarado's messengers by surrendering to Pedro de Alvarado and swearing loyalty to Spain, at which point Alvarado considered them pacified and returned to Iximche;[157] three days later, the lords of the Tzʼutujil arrived there to pledge their loyalty and offer tribute to the conquistadors.[158]

Reconnaissance of the Chiapas Highlands, 1524[]

In 1524 led a small party on a reconnaissance expedition into Chiapas.[159] He set out from Coatzacoalcos (renamed Espíritu Santo by the Spanish),[160] on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico.[40] His party followed the Grijalva upriver; near modern Chiapa de Corzo the Spanish party fought and defeated the Chiapanecos. Following this battle, Marín headed into the central highlands of Chiapas; around Easter he passed through the Tzotzil Maya town Zinacantan without opposition from the inhabitants.[161] The Zinacantecos, true to their pledge of allegiance two years earlier, aided the Spanish against the other indigenous peoples of the region.[162]

Marín was initially met by a peaceful embassy as he approached the Tzoztzil town of Chamula. He took this as the submission of the inhabitants, but was met by armed resistance when he tried to enter the province.[40] The Spanish found that the Chamula Tzotzil had abandoned their lands and stripped them of food in an attempt to discourage the invaders.[163] A day after their initial approach, Marín found that the Chamula Tzotzil had gathered their warriors upon a ridge that was too steep for the Spanish horses to climb. The conquistadors were met with a barrage of missiles and boiling water, and found the nearby town defended by a formidable 1.2-metre (4 ft) thick defensive wall. The Spanish stormed the wall, to find that the inhabitants had withdrawn under cover of torrential rain that had interrupted the battle.[164] After taking the deserted Chamula, the Spanish expedition continued against their allies at Huixtan. Again the inhabitants offered armed resistance before abandoning their town to the Spanish. Conquistador Diego Godoy wrote that the Indians killed or captured at Huixtan numbered no more than 500. The Spanish, by now disappointed with the scarce pickings, decided to retreat to Coatzacoalcos in May 1524.[165]

Kaqchikel rebellion, 1524–1530[]

Pedro de Alvarado rapidly began to demand gold in tribute from the Kaqchikels, souring the friendship between the two peoples,[166] and the Kaqchikel people abandoned their city and fled to the forests and hills on 28 August 1524. Ten days later the Spanish declared war on the Kaqchikel.[166]

The Kaqchikel began to fight the Spanish. They opened shafts and pits for the horses and put sharp stakes in them to kill them ... Many Spanish and their horses died in the horse traps. Many Kʼicheʼ and Tzʼutujil also died; in this way the Kaqchikel destroyed all these peoples.

Annals of the Kaqchikels[167]

The Spanish founded a new town at nearby Tecpán Guatemala, abandoned it in 1527 because of continuous Kaqchikel attacks, and moved to the Almolonga Valley to the east, refounding their capital at Ciudad Vieja.[168] The Kaqchikel kept up resistance against the Spanish for a number of years, but on 9 May 1530, exhausted by warfare,[169] the two kings of the most important clans returned from the wilds. A day later they were joined by many nobles and their families and many more people; they then surrendered at the new Spanish capital at Ciudad Vieja.[166] The former inhabitants of Iximche were dispersed; some were moved to Tecpán, the rest to Sololá and other towns around Lake Atitlán.[170]

Siege of Zaculeu, 1525[]

At the time of the conquest, the main Mam population was situated in Xinabahul (modern Huehuetenango city), but Zaculeu's fortifications led to its use as a refuge during the conquest.[171] The refuge was attacked by Gonzalo de Alvarado y Contreras, brother of Pedro de Alvarado,[172] in 1525, with 40 Spanish cavalry and 80 Spanish infantry,[173] and some 2,000 Mexican and Kʼicheʼ allies.[174] Gonzalo de Alvarado left the Spanish camp at Tecpán Guatemala in July 1525 and marched to Momostenango, which quickly fell to the Spanish after a four-hour battle. The following day Gonzalo de Alvarado marched on Huehuetenango and was confronted by a Mam army of 5,000 warriors from Malacatán. The Mam army advanced across the plain in battle formation and was met by a Spanish cavalry charge that threw them into disarray, with the infantry mopping up those Mam that survived the cavalry. The Mam leader Canil Acab was killed and the surviving warriors fled to the hills. The Spanish army rested for a few days, then continued onwards to Huehuetenango only to find it deserted.[173]

Kaybʼil Bʼalam had received news of the Spanish advance and had withdrawn to his fortress at Zaculeu,[173] with some 6,000 warriors gathered from the surrounding area.[175] The fortress possessed formidable defences, and Gonzalo de Alvarado launched an assault on the weaker northern entrance. Mam warriors initially held firm against the Spanish infantry but fell back before repeated cavalry charges. Kaybʼil Bʼalam, seeing that outright victory on an open battlefield was impossible, withdrew his army back within the safety of the walls. As Alvarado dug in and laid siege to the fortress, an army of approximately 8,000 Mam warriors descended on Zaculeu from the Cuchumatanes mountains to the north, drawn from towns allied with the city;[176] the relief army was annihilated by the Spanish cavalry.[177] After several months the Mam were reduced to starvation. Kaybʼil Bʼalam finally surrendered the city to the Spanish in the middle of October 1525.[178] When the Spanish entered the city they found 1,800 dead Indians, and the survivors eating the corpses.[174] After the fall of Zaculeu, a Spanish garrison was established at Huehuetenango, and Gonzalo de Alvarado returned to Tecpán Guatemala.[177]

Pedro de Alvarado in the Chiapas Highlands, 1525[]

A year after Luis Marín's reconnaissance expedition, Pedro de Alvarado entered Chiapas when he crossed a part of the Lacandon Forest in an attempt to link up with Hernán Cortés' expedition heading for Honduras.[179] Alvarado entered Chiapas from Guatemala via the territory of the Acala Chʼol; he was unable to locate Cortés, and his scouts eventually led him to Tecpan Puyumatlan (modern Santa Eulalia, Huehuetenango),[180] in a mountainous region near the territory of the Lakandon Chʼol.[181] The inhabitants of Tecpan Puyumatlan offered fierce resistance against the Spanish-led expedition, and Gonzalo de Alvarado wrote that the Spanish suffered many losses, including the killing of messengers sent to summon the natives to swear loyalty to the Spanish Crown.[41] After failing to locate Cortés, the Alvarados returned to Guatemala.[181]

Central and eastern Guatemalan Highlands, 1525–1532[]

In 1525 Pedro de Alvarado sent a small company to conquer Mixco Viejo (Chinautla Viejo), the capital of the Poqomam.[nb 3] The Spanish attempted an approach through a narrow pass but were forced back with heavy losses. Alvarado himself launched the second assault with 200 Tlaxcalan allies but was also beaten back. The Poqomam then received reinforcements, and the two armies clashed on open ground outside of the city. The battle was chaotic and lasted for most of the day, but was finally decided by the Spanish cavalry.[183] The leaders of the reinforcements surrendered to the Spanish three days after their retreat and revealed that the city had a secret entrance in the form of a cave.[184] Alvarado sent 40 men to cover the exit from the cave and launched another assault along the ravine, in single file owing to its narrowness, with crossbowmen alternating with musketmen, each with a companion sheltering him with a shield. This tactic allowed the Spanish to break through the pass and storm the entrance of the city. The Poqomam warriors fell back in disorder in a chaotic retreat through the city. Those who managed to retreat down the neighbouring valley were ambushed by Spanish cavalry who had been posted to block the exit from the cave, the survivors were captured and brought back to the city. The siege had lasted more than a month, and because of the defensive strength of the city, Alvarado ordered it to be burned and moved the inhabitants to the new colonial village of Mixco.[183]

There are no direct sources describing the conquest of the Chajoma by the Spanish but it appears to have been a drawn-out campaign rather than a rapid victory. After the conquest, the inhabitants of the kingdom were resettled in San Pedro Sacatepéquez, and San Martín Jilotepeque.[185] The Chajoma rebelled against the Spanish in 1526, fighting a battle at Ukubʼil, an unidentified site somewhere near the modern towns of San Juan Sacatepéquez and San Pedro Sacatepéquez.[186]

Chiquimula de la Sierra ("Chiquimula in the Highlands") was inhabited by Chʼortiʼ Maya at the time of the conquest.[187] The first Spanish reconnaissance of this region took place in 1524.[188] In 1526 three Spanish captains invaded Chiquimula on the orders of Pedro de Alvarado. The indigenous population soon rebelled against excessive Spanish demands, but the rebellion was quickly put down in April 1530.[189] However, the region was not considered fully conquered until a campaign by in 1531–1532 that also took in parts of Jalapa.[188] The afflictions of Old World diseases, war and overwork in the mines and encomiendas took a heavy toll on the inhabitants of eastern Guatemala, to the extent that indigenous population levels never recovered to their pre-conquest levels.[190]

Francisco de Montejo in Yucatán, 1527–28[]

The richer lands of Mexico engaged the main attention of the Conquistadors for some years, then in 1526 Francisco de Montejo (a veteran of the Grijalva and Cortés expeditions)[191] successfully petitioned the King of Spain for the right to conquer Yucatán. On 8 December of that year he was issued with the hereditary military title of adelantado and permission to colonise the Yucatán Peninsula.[192] In 1527 he left Spain with 400 men in four ships, with horses, small arms, cannon and provisions.[193] One of the ships was left at Santo Domingo as a supply ship to provide later support; the other ships set sail and reached Cozumel, an island off the east coast of Yucatán,[194] in the second half of September 1527. Montejo was received in there in peace by the lord Aj Naum Pat. The ships only stopped briefly before making for the mainland, making landfall somewhere near Xelha in the Maya province of Ekab.[195]

Montejo garrisoned Xelha with 40 soldiers and posted 20 more at nearby Pole.[195] Xelha was renamed Salamanca de Xelha and became the first Spanish settlement in the peninsula. The provisions were soon exhausted and additional food was requisitioned from the local Maya villagers; this too was soon consumed. Many local Maya fled into the forest and Spanish raiding parties scoured the surrounding area for food, finding little.[196] With discontent growing among his men, Montejo took the drastic step of burning his ships; this strengthened the resolve of his troops, who gradually acclimatised to the harsh conditions of Yucatán.[197] Montejo was able to get more food from the still-friendly Aj Nuam Pat of Cozumel.[196] Montejo took 125 men and set out on an expedition to explore the north-eastern portion of the Yucatán peninsula. At Belma, Montejo gathered the leaders of the nearby Maya towns and instructed them to swear loyalty to the Spanish Crown. After this, Montejo led his men to Conil, a town in Ekab, where the Spanish party halted for two months.[195]

In the spring of 1528, Montejo left Conil for the city of , which was abandoned by its Maya inhabitants under cover of darkness. The following morning the inhabitants attacked the Spanish party but were defeated. The Spanish then continued to Ake, where they engaged in a major battle, which left more than 1,200 Maya dead. After this Spanish victory, the neighbouring Maya leaders all surrendered. Montejo's party then continued to Sisia and Loche before heading back to Xelha.[195] Montejo arrived at Xelha with only 60 of his party, and found that only 12 of his 40-strong garrison survived, while the entire garrison at Pole had been slaughtered.[198]

The support ship eventually arrived from Santo Domingo, and Montejo used it to sail south along the coast, while he sent his second-in-command Alonso d'Avila via land. Montejo discovered the thriving port city of Chaktumal (modern Chetumal).[199] The Maya at Chaktumal fed false information to the Spanish, and Montejo was unable link up with d'Avila, who returned overland to Xelha. The fledgling Spanish colony was moved to nearby Xamanha,[200] modern Playa del Carmen, which Montejo considered to be a better port.[201] After waiting for d'Avila without result, Montejo sailed south as far as Honduras before turning around and heading back up the coast to finally meet up with his lieutenant at Xamanha. Late in 1528, Montejo left d'Avila to oversee Xamanha and sailed north to loop around the Yucatán Peninsula and head for the Spanish colony of New Spain in central Mexico.[200]

Conquest of the Chiapas Highlands, 1527–1547[]

|

| Maya civilization |

|---|

| History |

| Preclassic Maya |

| Classic Maya collapse |

| Spanish conquest of the Maya |

Pedro de Portocarrero, a young nobleman, led the next expedition into Chiapas after Alvarado, again from Guatemala. His campaign is largely undocumented but in January 1528 he successfully established the settlement of San Cristóbal de los Llanos in the Comitán valley, in the territory of the Tojolabal Maya.[202] This served as a base of operations that allowed the Spanish to extend their control towards the Ocosingo valley. One of the scarce mentions of Portocarrero's campaign suggests that there was some indigenous resistance but its exact form and extent is unknown.[41] Portocarrero established Spanish dominion over a number of Tzeltal and Tojolabal settlements, and penetrated as far as the Tzotzil town of Huixtan.[203]

By 1528, Spanish colonial power had been established in the Chiapas Highlands, and encomienda rights were being issued to individual conquistadores. Spanish dominion extended from the upper drainage of the Grijalva, across Comitán and Teopisca to the Ocosingo valley. The north and northwest were incorporated into the Villa de Espíritu Santo district, that included Chʼol Maya territory around Tila.[41] In the early years of conquest, encomienda rights effectively meant rights to pillage and round up slaves, usually in the form of a group of mounted conquistadores launching a lightning slave raid upon an unsuspecting population centre.[204] Prisoners would be branded as slaves, and were sold in exchange for weapons, supplies, and horses.[205]

Diego Mazariegos, 1528[]

In 1528, captain Diego Mazariegos crossed into Chiapas via the Isthmus of Tehuantepec with artillery and raw recruits recently arrived from Spain.[205] By this time, the indigenous population had been greatly reduced by a combination of disease and famine.[203] They first travelled to Jiquipilas to meet up with a delegation from Zinacantan, who had asked for Spanish assistance against rebellious vassals; a small contingent of Spanish cavalry was enough to bring these back into line. After this, Mazariegos and his companions proceeded to Chiapan and set up a temporary camp nearby, that they named Villa Real. Mazariegos had arrived with a mandate to establish a new colonial province of Chiapa in the Chiapas Highlands. He initially met with resistance from the veteran conquistadores who had already established themselves in the region.[205] Mazariegos heard that Pedro de Portocarrero was in the highlands, and sought him out in order to persuade him to leave. The two conquistadors eventually met up in Huixtan.[206] Mazariegos entered into protracted three-month negotiations with the Spanish settlers in Coatzacoalcos (Espíritu Santo) and San Cristóbal de los Llanos. Eventually an agreement was reached, and the encomiendas of Espíritu Santo that lay in the highlands were merged those of San Cristóbal to form the new province. Unknown to Mazariegos, the king had already issued an order that the settlements of San Cristóbal de los Llanos be transferred to Pedro de Alvarado. The end result of the negotiations between Mazariegos and the established settlers was that Villa de San Cristóbal de los Llanos was broken up, and those settlers who wished to remain were transferred to Villa Real, which had been moved to the fertile Jovel valley.[205] Pedro de Portocarrero left Chiapas and returned to Guatemala.[206] Mazariegos proceeded with the policy of moving the Indians into reducciones; this process was made easier by the much reduced indigenous population levels.[203] Mazariegos issued licences of encomienda covering still unconquered regions in order to encourage colonists to conquer new territory.[160] The Province of Chiapa had no coastal territory, and at the end of this process about 100 Spanish settlers were concentrated in the remote provincial capital at Villa Real, surrounded by hostile Indian settlements, and with deep internal divisions. [207]

Rebellion in the Chiapas Highlands, 1528[]

Although Mazariegos had managed to establish his new provincial capital without armed conflict, excessive Spanish demands for labour and supplies soon provoked the locals into rebellion. In August 1528, Mazariegos replaced the existing encomenderos with his friends and allies; the natives, seeing the Spanish isolated and witnessing the hostility between the original and newly arrived settlers, took this opportunity to rebel and refused to supply their new masters. Zinacantán was the only indigenous settlement that remained loyal to the Spanish.[207]

Villa Real was now surrounded by hostile territory, and any Spanish help was too far away to be of value. The colonists quickly ran short of food and responded by taking up arms and riding against the Indians in search of food and slaves. The Indians abandoned their towns and hid their women and children in caves. The rebellious populations concentrated themselves on easily defended mountaintops. At a lengthy battle was fought between the Tzeltal Maya and the Spanish, resulting in the deaths of a number of Spanish. The battle lasted several days, and the Spanish were supported by indigenous warriors from central Mexico. The battle eventually resulted in a Spanish victory, but the rest of the province of Chiapa remained rebellious.[207]

After the battle of Quetzaltepeque, Villa Real was still short on food and Mazariegos was ill; he retreated to Copanaguastla against the protests of the town council, which was left to defend the fledgling colony.[207] By now, Nuño de Guzmán was governor in Mexico, and he despatched Juan Enríquez de Guzmán to Chiapa as end-of-term judge over Mazariegos, and as alcalde mayor (a local colonial governor). He occupied his post for a year, during which time he attempted to reestablish Spanish control over the province, especially the northern and eastern regions, but was unable to make much headway.[160]

Founding of Ciudad Real, Chiapa, 1531–1535[]

In 1531, Pedro de Alvarado finally took up the post of governor of Chiapa. He immediately reinstated the old name of San Cristóbal de los Llanos upon Villa Real. Once again, the encomiendas of Chiapa were transferred to new owners. The Spanish launched an expedition against Puyumatlan; it was not successful in terms of conquest, but enabled the Spanish to seize more slaves to trade for weapons and horses. The newly acquired supplies would then be used in further expeditions to conquer and pacify still-independent regions, leading to a cycle of slave raids, trade for supplies, followed by further conquests and slave raids.[160] The Mazariegos family managed to establish a power base in the local colonial institutions and, in 1535, they succeeded in having San Cristóbal de los Llanos declared a city, with the new name of Ciudad Real. They also managed to acquire special privileges from the Crown in order to stabilise the colony, such as an edict that specified that the governor of Chiapa must govern in person and not through a delegated representative.[160] In practise, the quick turnover of encomiendas continued, since few Spaniards had legal Spanish wives and legitimate children who could inherit. This situation would not stabilise until the 1540s, when the dire shortage of Spanish women in the colony was alleviated by an influx of new colonists.[208]

Establishment of the Dominicans in Chiapa, 1545–1547[]

In 1542, the New Laws were issued with the aim of protecting the indigenous peoples of the Spanish colonies from their overexploitation by the encomenderos. Friar Bartolomé de las Casas and his followers left Spain in July 1544 to enforce the New Laws. Las Casas arrived in Ciudad Real with 16 fellow Dominicans on 12 March 1545.[209] The Dominicans were the first religious order to attempt the evangelisation of the native population. Their arrival meant that the colonists were no longer free to treat the natives as they saw fit without the risk of intervention by the religious authorities.[210] The Dominicans soon came into conflict with the established colonists. Colonial opposition to the Dominicans was such that the Dominicans were forced to flee Ciudad Real in fear of their lives. They established themselves nearby in two indigenous villages, the old site of Villa Real de Chiapa and Cinacantlán. From Villa Real, Bartolomé de las Casas and his companions prepared for the evangelisation of all the territory that fell within the .[209] The Dominicans promoted the veneration of Santiago Matamoros (St. James the Moor-slayer) as a readily identifiable image of Spanish military superiority.[211] The Dominicans soon saw the need to reestablish themselves in Ciudad Real, and the hostilities with the colonists were calmed.[212] In 1547, the first stone for the new Dominican convent in Ciudad Real was placed.[213]

Francisco de Montejo and Alonso d'Avila, Yucatán 1531–35[]

Montejo was appointed alcalde mayor (a local colonial governor) of Tabasco in 1529, and pacified that province with the aid of his son, also named Francisco de Montejo. D'Avila was sent from eastern Yucatán to conquer Acalan, which extended southeast of the Laguna de Terminos.[200] Montejo the Younger founded Salamanca de Xicalango as a base of operations. In 1530 d'Avila established Salamanca de Acalán as a base from which to launch new attempts to conquer Yucatán.[201] Salamanca de Acalán proved a disappointment, with no gold for the taking and with lower levels of population than had been hoped. D'Avila soon abandoned the new settlement and set off across the lands of the Kejache to Champotón, arriving there towards the end of 1530,[214] where he was later joined by the Montejos.[200]

In 1531 Montejo moved his base of operations to Campeche.[215] Alonso d'Avila was sent overland to the east of the peninsula, passing through Maní where he was well received by the . D'Avila continued southeast to Chetumal where he founded the Spanish town of Villa Real just within the borders of modern Belize.[216] The local Maya fiercely resisted the placement of the new Spanish colony and d'Avila and his men were forced to abandon it and make for Honduras in canoes.[200]

At Campeche, a strong Maya force attacked the city, but was repulsed by the Spanish.[217] Aj Canul, the lord of the attacking Maya, surrendered to the Spanish. After this battle, the younger Francisco de Montejo was despatched to the northern Cupul province, where the lord Naabon Cupul reluctantly allowed him to found the Spanish town of Ciudad Real at Chichen Itza. Montejo parcelled out the province amongst his soldiers as encomiendas. After six months of Spanish rule, Naabon Cupul was killed during a failed attempt to kill Montejo the Younger. The death of their lord only served to inflame Cupul anger and, in mid 1533, they laid siege to the small Spanish garrison at Chichen Itza. Montejo the Younger abandoned Ciudad Real by night, and he and his men fled west, where the Chel, Pech and Xiu provinces remained obedient to Spanish rule. Montejo the Younger was received in friendship by the lord of the Chel province. In the spring of 1534 he rejoined his father in the Chakan province at , (near modern Mérida).[218]

The Xiu Maya maintained their friendship with the Spanish throughout the conquest and Spanish authority was eventually established over Yucatán in large part due to Xiu support. The Montejos founded a new Spanish town at Dzilam, although the Spanish suffered hardships there.[218] Montejo the Elder returned to Campeche, where he was received with friendship by the local Maya. He was accompanied by the friendly Chel lord Namux Chel.[219] Montejo the Younger remained behind in Dzilam to continue his attempts at conquest of the region but soon retreated to Campeche to rejoin his father and Alonso d'Avila, who had returned to Campeche shortly beforehand. Around this time the news began to arrive of Francisco Pizarro's conquests in Peru and the rich plunder there. Montejo's soldiers began to abandon him to seek their fortune elsewhere; in seven years of attempted conquest in the northern provinces of the Yucatán Peninsula, very little gold had been found. Towards the end of 1534 or the beginning of the next year, Montejo the Elder and his son retreated to Veracruz, taking their remaining soldiers with them.[220]

Montejo the Elder became embroiled in colonial infighting over the right to rule Honduras, a claim that put him in conflict with Pedro de Alvarado, captain general of Guatemala, who also claimed Honduras as part of his jurisdiction. Alvarado was ultimately to prove successful. In Montejo the Elder's absence, first in central Mexico, and then in Honduras, Montejo the Younger acted as lieutenant governor and captain general in Tabasco.[220]

Conflict at Champoton[]

The Franciscan friar Jacobo de Testera arrived in Champoton in 1535 to attempt the peaceful incorporation of Yucatán into the Spanish Empire. His initial efforts were proving successful when Captain Lorenzo de Godoy arrived in Champoton at the command of soldiers despatched there by Montejo the Younger. Godoy and Testera were soon in conflict and the friar was forced to abandon Champoton and return to central Mexico.[220] Godoy's attempt to subdue the Maya around Champoton was unsuccessful,[221] so Montejo the Younger sent his cousin to take command; his diplomatic overtures to the Champoton Kowoj were successful and they submitted to Spanish rule. Champoton was the last Spanish outpost in the Yucatán Peninsula; it was increasingly isolated and the situation there became difficult.[222]

San Marcos: Province of Tecusitlán and Lacandón, 1533[]

In 1533 Pedro de Alvarado ordered de León y Cardona to explore and conquer the area around the Tacaná, Tajumulco, Lacandón and San Antonio volcanoes; in colonial times this area was referred to as the Province of Tecusitlán and Lacandón. De León marched to a Maya city named Quezalli by his Nahuatl-speaking allies with a force of fifty Spaniards; his Mexican allies also referred to the city by the name Sacatepequez. De León renamed the city as San Pedro Sacatepéquez.[223] The Spanish founded a village nearby at Candacuchex in April that year, renaming it as San Marcos.[224]

Campaigns in the Cuchumatanes and Lacandon Forest[]

In the ten years after the fall of Zaculeu various Spanish expeditions crossed into the Sierra de los Cuchumatanes and engaged in the gradual and complex conquest of the Chuj and Qʼanjobʼal.[225] The Spanish were attracted to the region in the hope of extracting gold, silver and other riches from the mountains but their remoteness, the difficult terrain and relatively low population made their conquest and exploitation extremely difficult.[226] The population of the Cuchumatanes is estimated to have been 260,000 before European contact. By the time the Spanish physically arrived in the region this had collapsed to 150,000 because of the effects of the Old World diseases that had run ahead of them.[82]

Eastern Cuchumatanes, 1529–1530[]

After Zaculeu fell to the Spanish, the Ixil and Uspantek Maya were sufficiently isolated to evade immediate Spanish attention. The Uspantek and the Ixil were allies and in 1529 Uspantek warriors were harassing Spanish forces and the city of Uspantán was trying to foment rebellion among the Kʼicheʼ; the Spanish decided that military action was necessary. , magistrate of Guatemala, penetrated the eastern Cuchumatanes with sixty Spanish infantry and three hundred allied indigenous warriors.[177] By early September he had imposed temporary Spanish authority over the Ixil towns of Chajul and Nebaj.[227] The Spanish army then marched east toward Uspantán; Arias then handed command over to the inexperienced and returned to the capital. Olmos launched a disastrous full-scale frontal assault on the city. As soon as the Spanish attacked, they were ambushed from the rear by over two thousand Uspantek warriors. The Spanish forces were routed with heavy losses; many of their indigenous allies were slain, and many more were captured alive by the Uspantek warriors only to be sacrificed.[228]

A year later set out from Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala (by now relocated to Ciudad Vieja) on another expedition, leading eight corporals, thirty-two cavalry, forty Spanish infantry and several hundred allied indigenous warriors. The expedition recruited further forces on the march north to the Cuchumatanes. On the steep southern slopes they clashed with between four and five thousand Ixil warriors; a lengthy battle followed during which the Spanish cavalry outflanked the Ixil army and forced them to retreat to their mountaintop fortress at Nebaj. The Spanish besieged the city, and their indigenous allies penetrated the stronghold and set it on fire. This allowed the Spanish to break the defences.[228] The victorious Spanish branded surviving warriors as slaves.[229] The inhabitants of Chajul immediately capitulated to the Spanish as soon as news of the battle reached them. The Spanish continued east towards Uspantán to find it defended by ten thousand warriors, including forces from Cotzal, Cunén, Sacapulas and Verapaz. Although heavily outnumbered, the Spanish cavalry and firearms decided the battle. The Spanish overran Uspantán and again branded all surviving warriors as slaves. The surrounding towns also surrendered, and December 1530 marked the end of the military stage of the conquest of the Cuchumatanes.[230]

Western Cuchumatanes and Lacandon Forest, 1529–1686[]

In 1529 the Chuj city of San Mateo Ixtatán (then known by the name of Ystapalapán) was given in encomienda to the conquistador Gonzalo de Ovalle together with Santa Eulalia and Jacaltenango. In 1549, the first reduction of San Mateo Ixtatán took place, overseen by Dominican missionaries,[231] in the same year the Qʼanjobʼal reducción settlement of Santa Eulalia was founded. Further Qʼanjobʼal reducciones were in place by 1560. Qʼanjobʼal resistance was largely passive, based on withdrawal to the inaccessible mountains and forests. In 1586 the Mercedarian Order built the first church in Santa Eulalia.[232] The Chuj of San Mateo Ixtatán remained rebellious and resisted Spanish control for longer than their highland neighbours, resistance that was possible owing to their alliance with the lowland Lakandon Chʼol to the north.[233]

By the mid-16th century, the Spanish frontier expanding outwards from Comitán and Ocosingo reached the Lacandon Forest, and further advancement was impeded by the region's fiercely independent inhabitants.[208] At the time of Spanish contact in the 16th century, the Lacandon Forest was inhabited by Chʼol people referred to as Lakam Tun. This name was Hispanicised to Lacandon.[234] The Lakandon were aggressive, and their numbers were swelled by refugees from neighbouring indigenous groups fleeing Spanish domination. The ecclesiastical authorities were so worried by this threat to their peaceful efforts at evangelisation that they eventually supported military intervention.[208] The first Spanish expedition against the Lakandon was carried out in 1559;[235] repeated expeditions into the Lacandon Forest succeeded in destroying some villages but did not manage to subdue the inhabitants of the region, nor bring it within the Spanish Empire. This successful resistance against Spanish attempts at domination served to attract ever more Indians fleeing colonial rule.[208]

In 1684, a council led by , the governor of Guatemala, decided on the reduction of San Mateo Ixtatán and nearby Santa Eulalia.[236] On 29 January 1686, Captain Melchor Rodríguez Mazariegos, acting under orders from the governor, left Huehuetenango for San Mateo Ixtatán, where he recruited indigenous warriors from the nearby villages.[237] To prevent news of the Spanish advance reaching the inhabitants of the Lacandon area, the governor ordered the capture of three of San Mateo's community leaders, and had them sent under guard to be imprisoned in Huehuetenango.[238] The governor joined Captain Rodríguez Mazariegos in San Mateo Ixtatán on 3 February; he ordered the captain to remain in the village and use it as a base of operations for penetrating the Lacandon region. Two Spanish missionaries also remained in the town.[239] Governor Enriquez de Guzmán subsequently left San Mateo Ixtatán for Comitán in Chiapas, to enter the Lacandon region via Ocosingo.[240]

Conquest of the Lakandon, 1695–1696[]

In 1695 the colonial authorities decided to act upon a plan to connect the province of Guatemala with Yucatán,[241] and a three-way invasion of the Lacandon was launched simultaneously from San Mateo Ixtatán, Cobán and Ocosingo.[242] Captain Rodriguez Mazariegos, accompanied by Fray de Rivas and 6 other missionaries together with 50 Spanish soldiers, left Huehuetenango for San Mateo Ixtatán.[243] Following the same route used in 1686,[242] they managed on the way to recruit 200 indigenous Maya warriors from Santa Eulalia, San Juan Solomá and San Mateo.[243] On 28 February 1695, all three groups left their respective bases of operations to conquer the Lacandon. The San Mateo group headed northeast into the Lacandon Jungle,[243] and joined up with , president of the Royal Audiencia of Guatemala.[244]

The soldiers commanded by Barrios Leal conquered a number of Chʼol communities.[245] The most important of these was Sakbʼajlan on the Lacantún River, which was renamed as Nuestra Señora de Dolores, or Dolores del Lakandon, in April 1695.[246] The Spanish built a fort and garrisoned it with 30 Spanish soldiers. Mercederian friar Diego de Rivas was based at Dolores del Lakandon, and he and his fellow Mercederians baptised several hundred Lakandon Chʼols in the following months and established contacts with neighbouring Chʼol communities.[247] The third group, under Juan Díaz de Velasco, marched from Verapaz against the Itza of northern Petén.[31] Barrios Leal was accompanied by Franciscan friar Antonio Margil,[248] who remained in Dolores del Lakandon until 1697.[248] The Chʼol of the Lacandon Forest were resettled in Huehuetenango, in the Guatemalan Highlands, in the early 18th century.[249]

Land of War: Verapaz, 1537–1555[]

By 1537 the area immediately north of the new colony of Guatemala was being referred to as the Tierra de Guerra ("Land of War").[250][nb 4] Paradoxically, it was simultaneously known as Verapaz ("True Peace").[252] The Land of War described an area that was undergoing conquest; it was a region of dense forest that was difficult for the Spanish to penetrate militarily. Whenever the Spanish located a centre of population in this region, the inhabitants were moved and concentrated in a new colonial settlement near the edge of the jungle where the Spanish could more easily control them. This strategy resulted in the gradual depopulation of the forest, simultaneously converting it into a wilderness refuge for those fleeing Spanish domination, both for individual refugees and for entire communities.[253] The Land of War, from the 16th century through to the start of the 18th century, included a vast area from Sacapulas in the west to Nito on the Caribbean coast and extended northwards from Rabinal and Salamá,[254] and was an intermediate area between the highlands and the northern lowlands.[255]

Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas arrived in the colony of Guatemala in 1537 and immediately campaigned to replace violent military conquest with peaceful missionary work.[256] Las Casas offered to achieve the conquest of the Land of War through the preaching of the Catholic faith.[257]

one could make a whole book ... out of the atrocities, barbarities, murders, clearances, ravages and other foul injustices perpetrated ... by those that went to Guatemala

Bartolomé de las Casas[258]

In this way they congregated a group of Christian Indians in the location of what is now the town of Rabinal.[259] Las Casas was instrumental in the introduction of the New Laws in 1542, established by the Spanish Crown to control the excesses of the colonists against the indigenous inhabitants of the Americas.[250] As a result, the Dominicans met substantial resistance from the Spanish colonists; this distracted the Dominicans from their efforts to establish peaceful control over the Land of War.[252]

In 1555 Spanish friar Domingo de Vico offended a local Chʼol ruler and was killed by the Acala Chʼol and their Lakandon allies.[260] In response to the killing, a punitive expedition was launched, headed by Juan Matalbatz, a Qʼeqchiʼ leader from Chamelco; the independent Indians captured by the Qʼeqchiʼ expedition were taken back to Cobán and resettled in Santo Tomás Apóstol.[261]

The Dominicans established themselves in Xocolo on the shore of Lake Izabal in the mid-16th century. Xocolo became infamous among the Dominican missionaries for the practice of witchcraft by its inhabitants. By 1574 it was the most important staging post for European expeditions into the interior, and it remained important in that role until as late as 1630, although it was abandoned in 1631.[262]

Conquest and settlement in northern Yucatán, 1540–46[]

In 1540 Montejo the Elder, who was now in his late 60s, turned his royal rights to colonise Yucatán over to his son, Francisco Montejo the Younger. In early 1541 Montejo the Younger joined his cousin in Champton; he did not remain there long, and quickly moved his forces to Campeche. Once there Montejo the Younger, commanding between three and four hundred Spanish soldiers, established the first permanent Spanish town council in the Yucatán Peninsula. Shortly afterwards, Montejo the Younger summoned the local Maya lords and commanded them to submit to the Spanish Crown. A number of lords submitted peacefully, including the ruler of the Xiu Maya. The lord of the Canul Maya refused to submit and Montejo the Younger sent his cousin against them (also called Francisco de Montejo); Montejo the Younger remained in Campeche awaiting reinforcements.[222]