Stephens City, Virginia

Stephens City, Virginia | |

|---|---|

Intersection of Routes 11 and 277 in the center of town | |

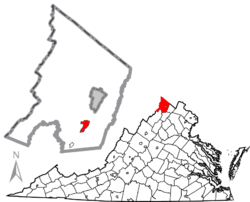

Location in Frederick County, Virginia | |

Stephens City, Virginia Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 39°4′59.45″N 78°13′5.96″W / 39.0831806°N 78.2183222°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Virginia |

| County | Frederick |

| Founded | October 12, 1758 |

| Founded by | Lewis Stephens |

| Named for | The Stephens family |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Mike Diaz[1] |

| • Town Council | show

Council members |

| • Delegate | Chris Collins (R)[3] |

| • VA Senate | Jill Holtzman Vogel (R)[3] |

| • U.S. Congress | Jennifer Wexton (D)[4] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.46 sq mi (6.36 km2) |

| • Land | 2.43 sq mi (6.28 km2) |

| • Water | 0.03 sq mi (0.08 km2) |

| Elevation | 764 ft (233 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 1,829 |

| • Estimate (2019)[7] | 2,063 |

| • Density | 850.37/sq mi (328.37/km2) |

| Demonym(s) | Stephens Citian |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 22655[8] |

| Area code(s) | 540 |

| FIPS code | 51-75344[6] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1500159[9] |

| Website | stephenscity |

Stephens City (/ˈstiːvənz/ STEE-vənz) is an incorporated town in the southern part of Frederick County, Virginia, United States, with a population of 1,829 at the time of the 2010 census.[6] and an estimated population in 2018 of 2,041.[10] Founded by Peter Stephens in the 1730s, the colonial town was chartered and named for Lewis Stephens in October 1758. It was originally settled by German Protestants from Heidelberg. Stephens City is the second-oldest municipality in the Shenandoah Valley after nearby Winchester, which is about 5 miles (8 km) to the north. "Crossroads", the first free black community in the Valley in the pre-Civil War years, was founded east of town in the 1850s. Crossroads remained until the beginning of the Civil War when the freed blacks either escaped or were recaptured. Stephens City was saved from intentional burning in 1864 by Union Major Joseph K. Stearns. The town has gone through several name changes in its history, starting as "Stephensburg", then "Newtown", and finally winding up as "Stephens City", though it nearly became "Pantops". Interstate 81 and U.S. Route 11 pass close to and through the town, respectively.

A large section of the center of the town, including buildings and homes, covering 65 acres (26 ha), is part of the Newtown–Stephensburg Historic District and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1992. Stephens City celebrated its 250th anniversary on October 12, 2008. The town is a part of the Winchester, Virginia-West Virginia Metropolitan Statistical Area, an offshoot of the Washington–Baltimore–Northern Virginia, DC–MD–VA–WV Combined Statistical Area. It is a member of the Winchester–Frederick County Metropolitan Planning Organization.[11]

History[]

Founding and early days[]

Jost Hite, a German immigrant, purchased a large land grant in the northern Shenandoah Valley in 1731.[12] Peter Stephens and a small party of German Protestants from Heidelberg, in the Palatinate, arrived about 1732 to buy and settle that land, including the site of what became Stephens City, named for the Stephens family.[13][14] Although Hite's title to the land was challenged by Thomas Fairfax, 6th Lord Fairfax of Cameron, the land baron of the area, the matter was settled amicably.[15][16][17]

Town lots were laid out beginning in 1754, and on September 21, 1758, Lewis Stephens petitioned the colonial government of Virginia in Williamsburg for a town charter.[15] The Virginia General Assembly approved the charter for the town of "Stephensburgh" on October 12, 1758.[18]:7 The mostly German-speaking residents soon left off the "h"; the town was usually spelled "Stephensburg". By the start of the Revolutionary War, Stephensburg was often called simply "New Town" or "Newtown", as the new settlement on the Great Wagon Road south of Winchester.[15]

Shenandoah Valley and Newtown's central location attracted heavy traffic through the region, and wagon-making emerged as an important industry for the town; Newtown artisans supplied wagons throughout the state.[19] By 1830, the town's population had reached 800.[20] In the late 1850s, free blacks began a settlement about a mile east of town which became known as "Crossroads" or "Freetown", which lasted until the time of the Civil War. After the January 1, 1863, Emancipation Proclamation, most of the newly freed slaves and many of the already free blacks left the area.[15]

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, the majority of Newtown's young men joined Confederate forces. During the war, the town was "between the lines", nominally controlled by the Union but with much Confederate partisan activity.[15][21] On May 24, 1862, Stonewall Jackson's Confederate forces advanced northward on the Valley Pike and attacked Union troops. At Newtown, General George Henry Gordon of the Second Massachusetts Infantry ordered his Federal troops to make a stand. The skirmishing involved heavy artillery fire, but Gordon's men retreated without loss of the important supply wagons. When Gordon left the town to Jackson's forces, both sides claimed a victory.[22]

In June 1864, Major Joseph K. Stearns of the 1st New York Cavalry arrived under orders to burn the town down to help stop Confederate ambushes on the wagon road. Because the remaining population mostly consisted of women, children and the elderly, Stearns allowed the town to stand. He required the adult residents to take the "Ironclad oath",[23][24] in which they swore that they had not voluntarily provided aid to the Confederacy. The government required the oath, effectively excluding ex-Confederates from the political arena during the Reconstruction era.[15]

In April 1867, the Virginia General Assembly granted a charter to the Winchester and Strasburg Railroad Company. The company was authorized to construct a rail line between Winchester and Strasburg, linking Newtown to the rest of the nation by railroad for the first time. Though the railroad improved the local economy, which had lagged after the end of the war, it decimated the wagon-building trade.[15] In 1880, the United States Post Office Department, faced with nearly a dozen Newtowns in Virginia, announced that the local post office would be renamed "Pantops". Dissatisfied with the name, the townsfolk chose "Stephens City".[25]

20th century to present[]

The 20th century brought improvements to energy and domestic systems: electrical service was introduced in 1915; and in 1941, just before World War II, the town installed a water system.[15] The construction of Interstate 81 (I-81) during the early 1960s depressed business development in the town. The wagon road, which had been made part of U.S. Route 11, had led traffic through the center of town, but the interstate passed less than a tenth of a mile to the east, drawing off development, retail trade and ultimately, businesses. This caused downtown to decline. Developers constructed new residential subdivisions both within and outside the town boundaries to the east for access to I-81.[15]

The town surveyed its older buildings to establish architectural significance and to determine those that contributed to the town's historic center. The Newtown–Stephensburg Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in August 1992.[26] Renovation of the town center has attracted heritage tourism. Anticipating more growth, the town annexed 360 acres (1.5 km2) of unincorporated Frederick County in 2005, another 100 acres (0.4 km2) in 2006, and 175 acres (0.7 km2) in 2007.[15] The town celebrated its 250th anniversary on October 12, 2008.[18]:125

Virginia school systems had practiced resistance following the United States Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) that segregated public schools were unconstitutional.[27] The United States District Court for the Western District of Virginia ordered Frederick County schools desegregated (including those serving Stephens City) in Brown v. County School Board (1964).[28] In 1994, Virgil E. Watson was elected as the first African American to serve on the Stephens City Town Council.[29] Watson served for one term, from 1994 until 1998.[29]

On September 17, 2004, remnants of Hurricane Ivan spawned an F1 tornado that touched down just south of the town along Interstate 81. It caused approximately $1 million in damage and injured two people.[30][31] It was one of a record 40 tornadoes to hit northern Virginia that day.[32]

Geography[]

The town is located between the Blue Ridge Mountains and the Appalachian Mountains in the northern Shenandoah Valley of Virginia in close proximity to West Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. Washington, D.C., is approximately 70 miles (110 km) to the east and the center of Baltimore is 105 miles (169 km) to the northeast by highway.[33]

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the town has an area of 2.4 square miles (6.3 km2), of which 0.03 square miles (0.08 km2), or 1.21%, are water.[6] The area within the town limits drains south to Stephens Run, a tributary of the Shenandoah River, and east and north to Opequon Creek, a direct tributary of the Potomac River.

Climate[]

Stephens City is located in the humid subtropical climate zone (Köppen climate classification: Cfa), exhibiting four distinct seasons.[34] Its climate is typical of Mid-Atlantic U.S. areas removed from bodies of water. The town is located in plant hardiness zone 7 throughout the town and surrounding Frederick County, indicating a temperate climate.[35] Spring and fall are warm, with low humidity, while winter is cool, with annual snowfall averaging 15.0 inches (38 cm).[36] Average winter lows tend to be around 30 °F (−1 °C) from mid-December to mid-February. Blizzards affect Stephens City on average once every four to six years. The most violent nor'easters typically feature high winds, heavy rains, and occasional snow. These storms often affect large sections of the U.S. East Coast.[36]

Summers are hot and humid; during this season, highs average in the upper 80s °F (lower 30s °C) and lows average in the upper 60s °F (lower 20s °C).[37] The combination of heat and humidity in the summer brings very frequent thunderstorms, some of which occasionally produce tornadoes in the area. While hurricanes (or their remnants) occasionally track through the area in late summer and early fall, they have often weakened by the time they reach Stephens City, partly due to the city's far inland location.

The highest recorded temperature was 107 °F (42 °C) in 1988, while the lowest recorded temperature was −18 °F (−28 °C) in 1983.[37]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperatures °F (°C) | |||||||||||||

| Average high | 40.8 | 44.7 | 53.9 | 64.8 | 74.2 | 82.6 | 87.1 | 85.7 | 78.8 | 67.5 | 56.2 | 45.7 | 65.2 |

| Average low | 20.0 | 22.2 | 30.3 | 38.5 | 48.7 | 57.3 | 62.0 | 60.1 | 52.9 | 40.6 | 32.5 | 24.5 | 40.8 |

| Highest recorded | 80 (1950) |

80 (1985) |

89 (1989) |

93 (1960) |

97 (2013) |

104 (2010) |

107 (1988) |

105 (2010) |

103 (1953) |

95 (1986) |

85 (1950) |

80 (2001) |

107 (1988) |

| Lowest recorded | −18 (1983) |

−16 (1996) |

−6 (1993) |

18 (1950) |

28 (1966) |

36 (1986) |

42 (1988) |

36 (1982) |

30 (1983) |

16 (1988) |

9 (1986) |

−6 (1989) |

−18 (1983) |

| Precipitation (inches) | |||||||||||||

| Monthly Average | 2.66 | 2.40 | 3.33 | 3.01 | 3.93 | 4.10 | 3.66 | 3.60 | 3.59 | 3.16 | 3.06 | 2.60 | 39.10 |

| Highest monthly | 5.92 (1978) |

5.67 (1998) |

8.36 (1993) |

7.07 (1987) |

9.40 (1988) |

12.67 (1972) |

7.35 (1978) |

7.89 (1975) |

11.31 (1999) |

9.01 (1976) |

7.33 (1997) |

5.55 (1973) |

12.67 (1972) |

| Snowfall (inches) | |||||||||||||

| Monthly Average | 7.9 | 6.7 | 2.4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | trace | 1.0 | 2.3 | 20.5 |

| Highest monthly | 35.0 (2016) |

33.0 (2010) |

17.0 (1984) |

3.0 (1971) |

0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | trace (1974) |

9.5 (1971) |

16.3 (1973) |

35.0 (2016) |

| Sources:[38][39] Notes: Temperatures are in degrees Fahrenheit. Precipitation includes rain and melted snow or sleet in inches; median values are provided for precipitation and snowfall because mean averages may be misleading. Mean and median values are for the 30-year period 1971–2000; temperature extremes are for the station's period of record (1900–2001). The station is located in 7 miles southeast of Winchester at approximately 39°6′1.45″N 78°10′49.29″W / 39.1004028°N 78.1803583°W and at 732 feet (223 m) in elevation. | |||||||||||||

Demographics[]

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 479 | — | |

| 1890 | 443 | −7.5% | |

| 1900 | 490 | 10.6% | |

| 1910 | 483 | −1.4% | |

| 1920 | 481 | −0.4% | |

| 1930 | 606 | 26.0% | |

| 1940 | 600 | −1.0% | |

| 1950 | 676 | 12.7% | |

| 1960 | 876 | 29.6% | |

| 1970 | 802 | −8.4% | |

| 1980 | 1,179 | 47.0% | |

| 1990 | 1,186 | 0.6% | |

| 2000 | 1,146 | −3.4% | |

| 2010 | 1,829 | 59.6% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 2,063 | [7] | 12.8% |

| [40][41] | |||

As of the 2010 United States Census, the population of Stephens City was 1,829 people in 743 households, and 447 families residing in the town. The total showed an increase of 59.6% from 2000.[40] The 2014 estimate placed the population at 1,921.[41] The racial makeup of the town was 85.1% White, 7.1% African American, 0.4% Native American, 1.8% Asian, and 2.8% from other races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 7.3% of the population.[40]

Of the 743 households in 2010, 28.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 38.5% were married couples living together, 14.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 39.8% were non-families.[40] 27.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 24.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older.[42] The average household size was 2.46 and the average family size was 3.06.[43] The age distribution was 24.1% under 18, 9.2% from 18 to 24, 31.5% from 25 to 44, 24.3% from 45 to 64, and 10.9% who were 65 or older.[44] The median age was 35.6 years.[44] The median income for a household in the town was $51,944,[45] and the median income for a family was $66,442.[46] In 2009, employed males had a median income of $31,875 versus $35,461 for employed females.[47] In 2009, the per capita income for the city was $20,581.[48]

On the 2010 Census, residents self-identified with a variety of ethnic ancestries; the major categories reflect descendants of the settlers of the 18th and 19th centuries. People of German descent make up 20.4% of the population of the town, followed by Irish at 11.2%, English at 7.3%, Italian at 5.4%, Scotch-Irish at 3.4%, Polish at 2.5%, Scottish at 2.4%, Dutch at 2.2%, Danish at 1.2%, French at 1.2%, Swedish at 1.1%, Austrian at 0.9%, Portuguese at 0.5%, European at 0.4%, Russian at 0.4%, Welsh at 0.4%, British at 0.3%, Canadian at 0.3%, Croatian at 0.2%, Slovak at 0.2%, Subsaharan African at 0.2%, and French Canadian rounding out at 0.2%.[49] 628 persons were of "other ancestries".[49]

Economy[]

The economy of Stephens City features several industries. According to the 2000 United States Census, the industries in the town (by percentage of employed civilian population 16 years and over) were manufacturing at 20.4%, educational, health and social services with 19.9%, retail trade at 12.8%, arts, entertainment, recreation, accommodation and food services with 9.0%, construction at 8.0%, other services (except public administration) with 6.8%, transportation, warehousing, and utilities at 4.6%, public administration with 3.9%, professional, scientific, management, administrative, and waste management services at 3.7%, finance, insurance, real estate, and rental and leasing with 3.4%, wholesale trade at 3.4%, information with 2.2% and agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting, and mining at 1.9%.[48]

Of the people in the labor force in the town over the age of 16, the majority, 597 people or 66.1% of the population, were in the civilian work force, while 306 people, or 33.9%, of the population were not in the labor force at all. At the time of the Census, only nine people, or 1.0%, were unemployed, with none in the Armed Forces. Of the 588 residents employed age 16 and over, private-sector wage and salary workers accounted for 457 of them or 77.7%. Ninety-five people were classified as federal government workers, or 16.2% of the population, with the self-employed making up 5.8% of the population or 34 people. Two people, or 0.3%, of the population were classified as unpaid workers.[48]

The median household income for the town of Stephens City was $35,200, with the majority, 126 persons, or 24.8%, of the population in that class of income. Eighty people, or 15.7%, identified themselves as retired.[48]

Culture[]

Town residents have access to two parks within town limits: Newtown Commons and Bel Air Street Park. Newtown Commons, sometimes called Newtown Park, is located along Main Street, and the other is on Bel Air Street.[50] At Newtown Commons, residents can hold outdoor events such as picnics, fundraisers or small concerts. The Bel Air Street Park is a playground for children with standard swingsets and other activities.[50]

Just outside Stephens City is Sherando Park. The park houses several trails, ponds, a pool, sports fields and more.[51] Sherando Park is also home of the Virginia Tech Memorial Garden, planted in memory of the Virginia Tech shooting, which took place approximately 175 miles (282 km) from the park. It has "a winding sidewalk shaped in the college's trademark 'VT'" and "a flagpole surrounded by 32 Hokie Stones", one for each of the 32 victims of the shooting.[52][53] The Memorial Garden was dedicated and opened on April 16, 2009, the second anniversary of the shooting.[52] The park was built by the Shenandoah Chapter of Virginia Tech Alumni Association, which is based in nearby Winchester, Virginia.[53]

The Family Drive-In Theatre, a two-screen drive-in theater, is located near the town, on U.S. Route 11 just south of Stephens City.[54][55] It is one of ten drive-ins in the state of Virginia.[56] The theatre converted to all-digital in 2013.[57] Stephens City plays host to the annual "Newtown Heritage Festival" held each Memorial Day weekend. The three-day event features many crafts, carnival-style food, a tractor wagon ride through town, local music at Newtown Commons, a parade on Saturday and fireworks.[58]

Stephens City is one of the towns along the Route 11 Yard Crawl. A yearly event held during the second Saturday in August, the Yard Crawl is an almost 50-mile-long (80 km) yard sale that stretches from Stephens City's Newtown Commons south along U.S. Route 11 to New Market, Virginia.[59][60] The event is sponsored by the Shenandoah County Chamber Advisory Group, five chambers of commerce, and the town of Stephens City.[59][60]

Government[]

In 2010, the head of Stephens City's government was Mayor Joy B. Shull, a former member of the Town Council, who was elected in an unopposed May 4 election, and served four years as mayor.[61] Shull succeeded Ray E. Ewing, who had served since 1994,[62] and retired at the end of his term.[63] The representative body of Stephens City is known as the Town Council, whose members (as of November 2012) include Ronald Bowers, Linden A. Fravel, Jr., James H. Harter, Joseph Hollis, Joseph Grayson and Martha W. Dilg.[2] Dilg was elected in a May 4, 2010, election to succeed Michael Grim, who left the Town Council at the end of his term.[64] Shull's replacement on Town Council was originally to be decided at a May 5, 2010, Town Council meeting[62] but was not announced until June 29, 2010, when Joseph Grayson was officially named to fill Shull's seat.[65] On November 6, 2012, Joseph Hollis, Joseph Grayson and Ronald Bowers were all reelected to the Stephens City Town Council.[66] Council member James Harter resigned on December 31, 2013, as he had moved outside of the town limits.[67]

The town council voted to appoint Jason Nauman to fill Harter's position on February 4, 2014.[68] Mayor Shull-Gellner announced in late July that she would be retiring after 34 years working for and with the town.[69] Her last day with the town is on July 31.[70] Town councilwoman Martha Dilg was appointed mayor on September 2, 2014.[71] In the November 4, 2014 election, Regina Swygert-Smith replaced Martha Dilg on the town's council. Councilmen Linden Fravel and Jason Nauman were reelected.[72][73] Mike Grim was elected mayor of the town, replacing Shull-Gellner who stepped down in July.[72][74]

As of 2014, the town is served by Police Chief Charles Bockey and Fire Chief Greg Locke, both of whom are on the town's Public Safety Committee.[2] The town is served by five other committees: the Administrative Committee, the Personnel Committee, the Water and Sewer Committee, the Public Works Committee, and the Finance Committee.[2] The members of those five committees are composed of Town Council members.[2]

Stephens City is represented by Chris Collins (Republican) in the Virginia House of Delegates 29th District.[3] Jill Holtzman Vogel (Republican) represents the town in the Virginia Senate's 27th District.[3] The town is represented by Jennifer Wexton (Democrat) in the U.S. House of Representatives from Virginia's 10th district.[4] Tim Kaine (Democrat) and Mark Warner (Democrat) represent the town in the United States Senate.[75]

Education[]

Frederick County Public Schools operate the public schools that serve Stephens City, although none are located within Stephens City proper; public schools that serve Stephens City are within a mile of the town limits. The town and surrounding area are served by Bass-Hoover Elementary School,[76] Robert E. Aylor Middle School (now relocated to White Post, Virginia) ,[77] and Sherando High School.[78] The latter was named for one of the historic Iroquoian-speaking tribes encountered by early European settlers to the Shenandoah Valley. Local private schools are available, and are also outside the town's corporate limits. Powhatan School is in nearby Boyce in Clarke County, Virginia.[79] Other smaller private or Christian-based schools are located throughout Frederick County and elsewhere in the area.

Transportation[]

Historic U.S. Route 11 traverses Stephens City proper, while Interstate 81 is located immediately east of the town line.[80] Stephens City serves as the western terminus of State Route 277, which begins at U.S. Route 11 and ends only 4.72 miles (7.60 km) away in Double Tollgate, Clarke County, Virginia, at U.S. Routes 340 and 522.[81]

Plans are in place to move State Route 277 to near the Family Drive-In Theatre, 0.50 miles (0.80 km) south of its current western terminus with US Route 11, with the eastern terminus remaining at its current location.[82][83] The planned construction will also move the I-81 interchange at Stephens City, where there are a number of service stations and fast food restaurants, south of the town limits to alleviate congestion on the current Route 277 bridge, which will remain after construction is completed. Planners expect expansion of Stephens City to the south.[82][83]

Religion[]

The earliest organized religious services in Stephens City began in 1790s when a Methodist Episcopal church was created in the town.[15] The first church structure, the "Methodist Episcopal Church in Stephensburg", dates from 1791. The current Stephens City United Methodist Church was constructed near that historic site.[84]

The oldest surviving church building in the town is Orrick Chapel, built between 1866 and 1869 as the home of an African Methodist Episcopal congregation. Missionaries from this first independent black denomination came South after the war to aid freedmen and plant new congregations; they attracted hundreds of thousands of new members. This church replaced an earlier Methodist chapel constructed in the late 1850s; it was razed by Union troops during the winter months of 1864–1865 near the end of the Civil War.[85]

As of 2010, within the town limits are congregations of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and United Methodist Church as well as those of the Baptist, Mennonite, Pentecostal, Charismatic Episcopal and Full Gospel denominations of Christianity.[86] Just south of the town limits is a Unitarian Universalist church.[87] A Roman Catholic parish affiliated with the Diocese of Arlington and a Jewish synagogue, which each function as centers for their respective members in the entire Shenandoah Valley, are located approximately 5 miles (8.0 km) north in Winchester.[88][89]

Notable people[]

- Timothy T. O'Donnell, author, professor (since 1992) and president (since 2002) of Christendom College[90]

- Kelley Washington, National Football League player[91]

References[]

- ^ "Town of Stephens City". Town of Stephens City. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Town Council". Town of Stephens City, Virginia. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Virginia State Legislative Directory". NAMI Virginia. January 28, 2014. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Find Your Representative in the U.S. House of Representatives". United States House of Representatives. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Stephens City town, Virginia". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on December 21, 2014. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ "Look Up a ZIP Code". United States Postal Service. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved November 8, 2018.

- ^ "Establishment of the Winchester – Frederick County ("Win-Fred") Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO)". Win-Fred MPO. Retrieved April 2, 2010.

- ^ Hofstra, Warren R. (2004). The Planting of New Virginia: Settlement and Landscape in the Shenandoah Valley. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 7–9.

- ^ Bly, Daniel W. (2002). From the Rhine to the Shenandoah: Eighteenth Century Swiss & German Pioneer Families in the Central Shenandoah Valley of Virginia and Their European Origins. 3. Baltimore: Gateway Press. pp. 171–200.

- ^ Hofstra, pp. 34, 94, 98–99

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k Smith, Byron C. "Town History". Newtown History Center of the Stone House Foundation (released under the GFDL). Retrieved November 17, 2007.

- ^ Hofstra, pp. 145–154

- ^ Brown, Stuart E. (1965). Virginia Baron: The Story of Thomas 6th Lord Fairfax. Berryville, Virginia: Chesapeake Book. pp. 35–123, 148–149.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fravel, Linden A.; Smith, Byron C. (October 6, 2008). Images of America: Stephens City. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738554396. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- ^ Martin, Joseph (1835). A New and Comprehensive Gazetteer of Virginia and the District of Columbia.

- ^ Howe, Henry (1845). Historical Collections of Virginia.

- ^ Fravel, Linden A. Between the Lines: The Civil War Diaries, Letters and Memoirs of the Steele Family of Newtown/Stephens City, Va., 1861 to 1864.

- ^ Steele, Inez Virginia. Early Days and Methodism in Stephens City, Virginia, 1732–1905 (1994 Reprint ed.). Geo. F. Norton Publishing (1906); Commercial Press (1994).

- ^ Duncan, Richard R. (2007). Beleaguered Winchester: a Virginia community at war, 1861–1865. Louisiana State University Press. pp. 192, 255. ISBN 978-0-8071-3217-3. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ Duncan, p. 255

- ^ Wine, J. Floyd (1987). "Frederick County Post Offices, Past and Present". Winchester Frederick County Historical Society Journal. Winchester Frederick County Historical Society. 2: 43–96.

- ^ Maral S. Kalbian (October 28, 1991). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Newtown-Stephensburg Historic District" (PDF). Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 11, 2010. Retrieved April 27, 2010. and Accompanying photo at Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission, undated Archived 2010-05-28 at the Wayback Machine and Accompanying map Archived 2016-08-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "BROWN V. BOARD: Timeline of School Integration in the U.S." Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- ^ Brown v. County School Board of Frederick County, Virginia, 234 F. Supp. 808 (United States District Court for the Western District of Virginia June 14, 1964).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Frederick County, Virginia v. Janet Reno, Attorney General of the United States; Bill Lann Lee, Acting Attorney Assistant General, Civil Rights Division (PDF). United States Department of Justice. p. 4. Retrieved August 2, 2012.

- ^ "National Weather Service Baltimore/Washington". National Weather Service Baltimore/Washington. October 20, 2004. Archived from the original on 2014-05-31. Retrieved March 26, 2010.

- ^ "Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena" (PDF). National Weather Service Baltimore/Washington. September 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-31. Retrieved March 26, 2010.

- ^ Watson, Barbara McNaught (January 7, 2008). "Virginia Tornadoes". VAEmergency.gov. Virginia Department of Emergency Management. Archived from the original on May 31, 2014. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

Sept. 17, 2004: "Ivan" spawned 29 F0/F1 tornadoes, 10 strong F2 tornadoes and one strong F3 tornado

- ^ "Google maps". Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- ^ "World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated". University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna. November 6, 2008. Archived from the original on September 6, 2010. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- ^ "Hardiness Zones". National Arbor Day Foundation. 2006. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b McNaught Watson, Barbara (December 30, 2005). "Virginia Winters". National Weather Service – Weather Forecast Office Baltimore/Washington. Archived from the original on 2015-10-30. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Stephens City Historic Weather Averages in Virginia (22655)". Intellicast/NBCUniversal. Retrieved November 29, 2014.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals 1971-2000, Products" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/National Climatic Data Center. 2004. Retrieved May 15, 2015.

- ^ "NWS Sterling - February 6, 2010 Event page". National Weather Service. February 6, 2010. Archived from the original on 2015-10-25. Retrieved October 22, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Population Estimate Data - Virginia - Census.gov". United States Census Bureau. 2014. Archived from the original on June 29, 2015. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- ^ "Tenure, Household Size, and Age of Householder: 2010". United States Census Bureau. December 2010. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ "Households and Families: 2010". United States Census Bureau. December 2010. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Age Groups and Sex: 2010". United States Census Bureau. December 2010. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ "Median Household Income in the Past 12 Months (in 2010 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars)". United States Census Bureau. December 2010. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ "Median Household Income in the Past 12 Months (in 2011 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars) By Household Size". United States Census Bureau. December 2010. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ "Median Income in the Past 12 Months (In 2009 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars)". United States Census Bureau. 2009. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Per Capita Income in the Past 12 Months (In 2009 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars)". United States Census Bureau. 2009. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Total Ancestry Reported - Universe: Total ancestry categories tallied for people with one or more ancestry categories reported 2006-2010". United States Census Bureau. December 2010. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Frequently Asked Questions". Town of Stephens City. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ "Parks and Recreation – Sherando Park". County of Frederick, Virginia. Archived from the original on December 11, 2013. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "We Remember - Shenandoah Chapter Virginia Tech Alumni Association". Shenandoah Chapter Virginia Tech Alumni Association. Archived from the original on December 22, 2017. Retrieved December 16, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "General Tributes - VTV Family Outreach Foundation". VTV Family Outreach Foundation. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

- ^ Carney, Dan (July 1, 2011). "In western Virginia, the drive-in movie theater lives on". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

- ^ "Family Drive-In Theatre". Colonial Entertainment Group, LLC. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- ^ Fraley, Jason (August 24, 2012). "Stephens City proves drive-ins are not 'expendable'". WTOP Radio. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ Bradshaw, Vic (September 3, 2013). "At Family Drive-In, show goes on, and on, and on". The Winchester Star. Winchester, Virginia: Byrd Newspapers. Archived from the original on November 8, 2014. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

- ^ "Newtown Heritage Festival". Town of Stephens City. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Voth, Sally (August 3, 2012). "Shenandoah County Yard Crawl next weekend". Northern Virginia Daily. Archived from the original on 2014-12-20. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cornell, Ryan (July 23, 2013). "Bargain hunters gear up for Route 11 Yard Crawl". Northern Virginia Daily. Archived from the original on 2014-12-20. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ^ Davis, Brandon (April 28, 2010). "Meet Stephens City's next mayor" (PDF). The Sherando Times. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-16. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Stephens City picks new mayor". Northern Virginia Daily. May 5, 2010. Archived from the original on 2014-02-21. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ Williams, J. R. (April 29, 2010). "Candidates ready for council elections". Northern Virginia Daily. Archived from the original on 2012-10-02. Retrieved July 22, 2010.

- ^ "May 4, 2010 Town Elections Unofficial Results". Virginia State Board of Elections. May 4, 2010. Archived from the original on October 2, 2011. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ^ "Shull sworn in as mayor of town". Northern Virginia Daily. Stephens City, Virginia. June 30, 2010.

- ^ "Unofficial Results - General Election - November 6, 2012". Virginia State Board of Elections. November 6, 2012. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved November 10, 2012.

- ^ Bridges, Alex (January 27, 2014). "Stephens City leaders to fill council seat". Northern Virginia Daily. Archived from the original on 2014-12-20. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- ^ Bridges, Alex (February 5, 2014). "Town Council fills seat, hears interest in school". Northern Virginia Daily. Archived from the original on 2014-12-20. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- ^ Armstrong, Matt (July 25, 2014). "Town mayor reflects as retirement nears". The Winchester Star. Archived from the original on August 5, 2014. Retrieved July 25, 2014.

- ^ Cornell, Ryan (July 25, 2014). "Town mayor reflects as retirement nears". Northern Virginia Daily. Archived from the original on 2014-12-20. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ Cornell, Ryan (September 4, 2014). "Tree trimming angers council". Northern Virginia Daily. Archived from the original on 2014-12-20. Retrieved September 4, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cornell, Ryan (November 4, 2014). "Middletown, Stephens City council seats filled". Northern Virginia Daily. Archived from the original on 2014-12-20. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- ^ "Virginia Elections Database >> 2014 Town Council General Election Frederick County - Stephens City". Virginia State Board of Elections. November 4, 2014. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

- ^ "Virginia Elections Database >> 2014 Mayor General Election Frederick County - Stephens City". Virginia State Board of Elections. November 4, 2014. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

- ^ "Senators of the 113th Congress - Virginia". United States Senate. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- ^ "Bass-Hoover Elementary School". Frederick County Public Schools. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- ^ "Robert E. Aylor Middle School". Frederick County Public Schools. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- ^ "Sherando High School". Frederick County Public Schools. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- ^ "Directions". Powhatan School. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ "Welcome to the Frederick County Interactive Mapping Website". Frederick County Information Technologies GIS Division. Retrieved March 26, 2010.

- ^ "VA 261 to 280". Adam Froehlig and Mike Roberson. December 16, 2011. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Route 277 Triangle and Urban Center Plan". Frederick County (Virginia) Department of Planning and Development. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Area Plan - Route 277 Triangle and Urban Center Land Use Plan". Frederick County (Virginia) Department of Planning and Development. July 14, 2011. Archived from the original on May 31, 2014. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- ^ "SCUMC History". Stephens City United Methodist Church. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ History of Orrick Chapel Methodist Church in Stephens City, Virginia (PDF). Newtown History Center of The Stone House Foundation. pp. 3–5. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- ^ "Schools and Churches". Town of Stephens City. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ "UUCSV". Unitarian Universalist Church of the Shenandoah Valley. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ "Sacred Heart of Jesus Roman Catholic Church". Sacred Heart of Jesus Roman Catholic Church. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ "Beth El Congregation". Beth El Congregation. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ "Undergraduate Faculty". Christendom College. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- ^ "Kelley Washington". Yahoo Sports/NBC Sports Network/Stats LLC/Opta. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stephens City, Virginia. |

|

|

|

- Stephens City, Virginia

- Towns in Frederick County, Virginia

- Towns in Virginia

- Populated places established in 1758

- 1758 establishments in Virginia