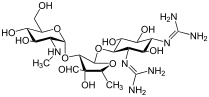

Streptomycin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data |

|

| Routes of administration | Intramuscular, intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 84% to 88% IM (est.)[1] 0% by mouth |

| Elimination half-life | 5 to 6 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.323 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H39N7O12 |

| Molar mass | 581.580 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 12 °C (54 °F) |

| | |

| Look up streptomycin in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Streptomycin is an antibiotic medication used to treat a number of bacterial infections,[3] including tuberculosis, Mycobacterium avium complex, endocarditis, brucellosis, Burkholderia infection, plague, tularemia, and rat bite fever.[3] For active tuberculosis it is often given together with isoniazid, rifampicin, and pyrazinamide.[4] It is administered by injection into a vein or muscle.[3]

Common side effects include vertigo, vomiting, numbness of the face, fever, and rash.[3] Use during pregnancy may result in permanent deafness in the developing baby.[3] Use appears to be safe while breastfeeding.[4] It is not recommended in people with myasthenia gravis or other neuromuscular disorders.[4] Streptomycin is an aminoglycoside.[3] It works by blocking the ability of 30S ribosomal subunits to make proteins, which results in bacterial death.[3]

Albert Schatz first isolated streptomycin in 1943 from Streptomyces griseus.[5][6] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[7] The World Health Organization classifies it as critically important for human medicine.[8]

Uses[]

Medication[]

- Infective endocarditis: An infection of the endocardium caused by enterococcus; used when the organism is not sensitive to gentamicin[medical citation needed]

- Tuberculosis: Used in combination with other antibiotics. For active tuberculosis it is often given together with isoniazid, rifampicin, and pyrazinamide.[4] It is not the first-line treatment, except in medically under-served populations where the cost of more expensive treatments is prohibitive. It may be useful in cases where resistance to other drugs is identified.[medical citation needed]

- Plague (Yersinia pestis): Has historically been used as the first-line treatment. However streptomycin is approved for this purpose only by the US Food and Drug Administration.[medical citation needed]

- In veterinary medicine, streptomycin is the first-line antibiotic for use against gram negative bacteria in large animals (horses, cattle, sheep, etc.). It is commonly combined with procaine penicillin for intramuscular injection.[medical citation needed]

- Tularemia infections have been treated mostly with streptomycin.[9]

Streptomycin is traditionally given intramuscularly, and in many nations is only licensed to be administered intramuscularly, though in some regions the drug may also be administered intravenously.[1]

Pesticide[]

Streptomycin also is used as a pesticide, to combat the growth of bacteria beyond human applications. Streptomycin controls bacterial diseases of certain fruit, vegetables, seed, and ornamental crops. A major use is in the control of fireblight on apple and pear trees. As in medical applications, extensive use can be associated with the development of resistant strains. Streptomycin could potentially be used to control cyanobacterial blooms in ornamental ponds and aquaria.[10] While some antibacterial antibiotics are inhibitory to certain eukaryotes, this seems not to be the case for streptomycin, especially in the case of anti-fungal activity.[11]

Cell culture[]

Streptomycin, in combination with penicillin, is used in a standard antibiotic cocktail to prevent bacterial infection in cell culture.[medical citation needed]

Protein purification[]

When purifying protein from a biological extract, streptomycin sulfate is sometimes added as a means of removing nucleic acids. Since it binds to ribosomes and precipitates out of solution, it serves as a method for removing rRNA, mRNA, and even DNA if the extract is from a prokaryote.[medical citation needed]

Side effects[]

The most concerning side effects, as with other aminoglycosides, are kidney toxicity and ear toxicity.[12] Transient or permanent deafness may result. The vestibular portion of cranial nerve VIII (the vestibulocochlear nerve) can be affected, resulting in tinnitus, vertigo, ataxia, kidney toxicity, and can potentially interfere with diagnosis of kidney malfunction.[13]

Common side effects include vertigo, vomiting, numbness of the face, fever, and rash. Fever and rashes may result from persistent use.[citation needed]

Use is not recommended during pregnancy.[3] Congenital deafness has been reported in children whose mothers received streptomycin during pregnancy.[3] Use appears to be okay while breastfeeding.[4]

It is not recommended in people with myasthenia gravis.[4]

Mechanism of action[]

Streptomycin has two mechanism of action depending on what conformation (isomer) is at in the system in which it will work. Isomer A functions as a protein synthesis inhibitor. It binds to the small 16S rRNA of the 30S subunit of the bacterial ribosome irreversibly, interfering with the binding of formyl-methionyl-tRNA to the 30S subunit.[14] This leads to codon misreading, eventual inhibition of protein synthesis and ultimately death of microbial cells through mechanisms that are still not understood. Speculation on this mechanism indicates that the binding of the molecule to the 30S subunit interferes with 30S subunit association with the mRNA strand. This results in an unstable ribosomal-mRNA complex, leading to a frameshift mutation and defective protein synthesis; leading to cell death.[15] Humans have ribosomes which are structurally different from those in bacteria, so the drug does not have this effect in human cells. At low concentrations, however, streptomycin only inhibits growth of the bacteria by inducing prokaryotic ribosomes to misread mRNA.[16]

Streptomycin isomer B is a peptidoglycan synthesis inhibitor much like lysozyme. It binds to the glycosidic linkages and breaks them through a SN2 mechanism. This leads to bacterial cell walls' integrity being compromised, ultimately resulting in death of microbial cells.

Streptomycin is an antibiotic that inhibits both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria,[17] and is therefore a useful broad-spectrum antibiotic.

History[]

Streptomycin was first isolated on October 19, 1943, by Albert Schatz, a PhD student in the laboratory of Selman Abraham Waksman at Rutgers University in a research project funded by Merck and Co.[18][19] Waksman and his laboratory staff discovered several antibiotics, including actinomycin, clavacin, , streptomycin, , neomycin, , candicidin, and . Of these, streptomycin and neomycin found extensive application in the treatment of numerous infectious diseases. Streptomycin was the first antibiotic cure for tuberculosis (TB). In 1952 Waksman was the recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in recognition "for his discovery of streptomycin, the first antibiotic active against tuberculosis".[20] Waksman was later accused of playing down the role of Schatz who did the work under his supervision, claiming that Elizabeth Bugie had a more important role in its development.[21][22][23][24]

The Rutgers team reported streptomycin in the medical literature in January 1944.[25] Within months they began working with William Feldman and H. Corwin Hinshaw of the Mayo Clinic with hopes of starting a human clinical trial of streptomycin in tuberculosis.[26]:209–241 The difficulty at first was even producing enough streptomycin to do a trial, because the research laboratory methods of creating small batches had not yet been translated to commercial large-batch production. They managed to do an animal study in a few guinea pigs with just 10 grams of the scarce drug, demonstrating survival.[26]:209–241 This was just enough evidence to get Merck & Co. to divert some resources from the young penicillin production program to start work toward streptomycin production.[26]:209–241

At the end of World War II, the United States Army experimented with streptomycin to treat life-threatening infections at a military hospital in Battle Creek, Michigan. The first person who was treated with streptomycin did not survive; the second person survived but became blind as a side effect of the treatment. In March 1946, the third person—Robert J. Dole, later Majority Leader of the United States Senate and presidential nominee—experienced a rapid and robust recovery.[27]

The first randomized trial of streptomycin against pulmonary tuberculosis was carried out in 1946 through 1948 by the MRC Tuberculosis Research Unit under the chairmanship of Geoffrey Marshall (1887–1982). The trial was neither double-blind nor placebo-controlled.[28] It is widely accepted to have been the first randomised curative trial.[29]

Results showed efficacy against TB, albeit with minor toxicity and acquired bacterial resistance to the drug.[28]

New Jersey[]

Because streptomycin was isolated from a microbe discovered on New Jersey soil, and because of its activity against tuberculosis and Gram negative organisms, and in recognition of both the microbe and the antibiotic in the history of New Jersey, S. griseus was nominated as the Official New Jersey state microbe. The draft legislation was submitted by Senator Sam Thompson (R-12) in May 2017 as bill S3190 and Assemblywoman Annette Quijano (D-20) in June 2017 as bill A31900.[30][31]

See also[]

- Philip D'Arcy Hart – The British medical researcher and pioneer in tuberculosis treatment in the early twentieth century.

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Zhu M, Burman WJ, Jaresko GS, Berning SE, Jelliffe RW, Peloquin CA (October 2001). "Population pharmacokinetics of intravenous and intramuscular streptomycin in patients with tuberculosis". Pharmacotherapy. 21 (9): 1037–1045. doi:10.1592/phco.21.13.1037.34625. PMID 11560193. S2CID 24111273. Archived from the original on October 5, 2011. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ^ "Streptomycin Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. October 24, 2019. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i "Streptomycin Sulfate". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. pp. 136, 144, 609. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- ^ Torok, Estee; Moran, Ed; Cooke, Fiona (2009). Oxford Handbook of Infectious Diseases and Microbiology. OUP Oxford. p. Chapter 2. ISBN 9780191039621. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017.

- ^ Renneberg, Reinhard; Demain, Arnold L. (2008). Biotechnology for Beginners. Elsevier. p. 103. ISBN 9780123735812. Archived from the original on September 10, 2017.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). Critically important antimicrobials for human medicine (6th revision ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/312266. ISBN 9789241515528. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ "Clinicians Tularemia". www.cdc.gov. September 2016. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- ^ Qian H, Li J, Pan X, Sun Z, Ye C, Jin G, Fu Z (March 2012). "Effects of streptomycin on growth of algae Chlorella vulgaris and Microcystis aeruginosa". Environ. Toxicol. 27 (4): 229–37. Bibcode:2012EnTox..27..229Q. doi:10.1002/tox.20636. PMID 20725941. S2CID 2380252.

- ^ Reilly HC, Schatz A, Waksman SA (June 1945). "Antifungal Properties of Antibiotic Substances". J. Bacteriol. 49 (6): 585–94. doi:10.1128/jb.49.6.585-594.1945. PMC 374091. PMID 16560957.

- ^ Prayle A, Watson A, Fortnum H, Smyth A (July 2010). "Side effects of aminoglycosides on the kidney, ear and balance in cystic fibrosis". Thorax. 65 (7): 654–8. doi:10.1136/thx.2009.131532. PMC 2921289. PMID 20627927.

- ^ Syal K, Srinivasan A, Banerjee D (2013). "Streptomycin interference in Jaffe reaction — Possible false positive creatinine estimation in excessive dose exposure". Clinical Biochemistry. 46 (1–2): 177–179. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2012.10.031. PMID 23123914.

- ^ Sharma D, Cukras AR, Rogers EJ, Southworth DR, Green R (December 7, 2007). "Mutational analysis of S12 protein and implications for the accuracy of decoding by the ribosome". Journal of Molecular Biology. 374 (4): 1065–76. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2007.10.003. PMC 2200631. PMID 17967466.

- ^ Raymon, Lionel P. (2011). COMLEX Level 1 Pharmacology Lecture Notes. Miami, FL: Kaplan, Inc. p. 181. CM4024K.

- ^ Voet, Donald & Voet, Judith G. (2004). Biochemistry (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 1341. ISBN 978-0-471-19350-0.

- ^ Jan-Thorsten Schantz; Kee-Woei Ng (2004). A manual for primary human cell culture. World Scientific. p. 89.

- ^ Comroe JH Jr (1978). "Pay dirt: the story of streptomycin. Part I: from Waksman to Waksman". American Review of Respiratory Disease. 117 (4): 773–781. doi:10.1164/arrd.1978.117.4.773 (inactive May 31, 2021). PMID 417651.CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of May 2021 (link)

- ^ Kingston W (July 2004). "Streptomycin, Schatz v. Waksman, and the balance of credit for discovery". J Hist Med Allied Sci. 59 (3): 441–62. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrh091. PMID 15270337. S2CID 27465970.

- ^ Official list of Nobel Prize Laureates in Medicine Archived June 9, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wainwright, M. (1990). Miracle Cure: The Story of Penicillin and the Golden Age of Antibiotics. Blackwell. ISBN 9780631164920. Archived from the original on September 10, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ^ Wainwright M (1991). "Streptomycin: discovery and resultant controversy". Hist Philos Life Sci. 13 (1): 97–124. PMID 1882032.

- ^ Kingston, William (July 1, 2004). "Streptomycin, Schatz v. Waksman, and the balance of credit for discovery". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 59 (3): 441–462. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrh091. ISSN 0022-5045. PMID 15270337. S2CID 27465970.

- ^ Pringle, Peter (2012). Experiment Eleven: Dark Secrets Behind the Discovery of a Wonder Drug. New York: Walker & Company. ISBN 978-1620401989.

- ^ Schatz, Albert; Bugle, Elizabeth; Waksman, Selman A. (1944), "Streptomycin, a substance exhibiting antibiotic activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria", Experimental Biology and Medicine, 55: 66–69, doi:10.3181/00379727-55-14461, S2CID 33680180.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ryan, Frank (1993). The forgotten plague: how the battle against tuberculosis was won—and lost. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0316763806.

- ^ Cramer, Richard Ben, What It Takes (New York, 1992), pp. 110-11.

- ^ Jump up to: a b D'Arcy Hart P (August 1999). "A change in scientific approach: from alternation to randomised allocation in clinical trials in the 1940s". BMJ. 319 (7209): 572–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7209.572. PMC 1116443. PMID 10463905.

- ^ Metcalfe NH (February 2011). "Sir Geoffrey Marshall (1887-1982): respiratory physician, catalyst for anaesthesia development, doctor to both Prime Minister and King, and World War I Barge Commander". J Med Biogr. 19 (1): 10–4. doi:10.1258/jmb.2010.010019. PMID 21350072. S2CID 39878743.

- ^ "New Jersey S3190 | 2016-2017 | Regular Session". LegiScan. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- ^ "New Jersey A4900 | 2016-2017 | Regular Session". LegiScan. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

Further reading[]

- "Notebooks Shed Light on an Antibiotic's Contested Discovery," The New York Times, June 12, 2012, by Peter Pringle

- Kingston, William (2004). "Streptomycin, Schatz v. Waksman, and the Balance of Credit for Discovery". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 59 (3): 441–462. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrh091. PMID 15270337. S2CID 27465970.

- Mistiaen, Veronique (November 2, 2002). "Time, and the great healer". The Guardian.. The history behind the discovery of streptomycin.

- EPA R.E.D. Facts sheet on use of streptomycin as a pesticide.

External links[]

- "Streptomycin". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Aminoglycoside antibiotics

- Anti-tuberculosis drugs

- Guanidines

- World Health Organization essential medicines