Sub-Saharan Africa

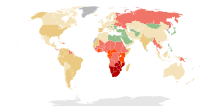

Dark and lighter green: Definition of "sub-Saharan Africa" as used in the statistics of the United Nations institutions. Lighter green: However, Sudan is classified as Northern Africa by the United Nations Statistics Division,[1] though the organisation states "the assignment of countries or areas to specific groupings is for statistical convenience and does not imply any assumption regarding political or other affiliation of countries or territories". | |

| Population | The population in Sub-Saharan Africa is growing and according to Global Trends in 2019 the population was 1.1 billion. 1,038,627,178 (2018) |

|---|---|

| Religions |

|

| Languages | Over 1,000 languages |

| Internet TLD | .africa |

| Major cities |

|

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. According to the United Nations, it consists of all African countries and territories that are fully or partially south of the Sahara.[3] While the United Nations geoscheme for Africa excludes Sudan from its definition of sub-Saharan Africa, the African Union's definition includes Sudan but instead excludes Mauritania.

It contrasts with North Africa, which is frequently grouped within the MENA ("Middle East and North Africa") region, and most of whose states are members of the Arab League (largely overlapping with the term "Arab world"). The states of Somalia, Djibouti, Comoros, and the Arab-majority Mauritania (and sometimes Sudan) are, however, geographically considered part of sub-Saharan Africa, although they are members of the Arab League as well.[4] The United Nations Development Program lists 46 of Africa's 54 countries as "sub-Saharan", excluding Algeria, Djibouti, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, Somalia, Sudan and Tunisia.[5]

Since probably 3500 BCE,[6][7] the Saharan and sub-Saharan regions of Africa have been separated by the extremely harsh climate of the sparsely populated Sahara, forming an effective barrier interrupted by only the Nile in Sudan, though navigation on the Nile was blocked by the river's cataracts. The Sahara pump theory explains how flora and fauna (including Homo sapiens) left Africa to penetrate the Middle East and beyond. African pluvial periods are associated with a Wet Sahara phase, during which larger lakes and more rivers existed.[8]

Nomenclature[]

The ancient Greeks sometimes referred to sub-Saharan Africa as Aethiopia, but sometimes also applied this name more specifically to a state, originally applied to the Kingdom of Kush and the Sudan area, but then usurped by Axum in the 4th century which led to the name being designated to the nation of Ethiopia

Geographers historically divided the region into several distinct ethnographic sections based on each area's respective inhabitants.[9]

Commentators in Arabic in the medieval period used the general term bilâd as-sûdân ("Land of the Blacks") for the vast Sudan region (an expression denoting West and Central Africa),[10] or sometimes extending from the coast of West Africa to Western Sudan.[11] Its equivalent in Southeast Africa was Zanj ("Country of the Blacks"), which was situated in the vicinity of the Great Lakes region.[9][11]

The geographers drew an explicit ethnographic distinction between the Sudan region and its analogue Zanj, from the area to their extreme east on the Red Sea coast in the Horn of Africa.[9] In modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea was Al-Habash or Abyssinia,[12] which was inhabited by the Habash or Abyssinians, who were the forebears of the Habesha.[13] In northern Somalia was Barbara or the Bilad al-Barbar ("Land of the Berbers"), which was inhabited by the Eastern Baribah or Barbaroi, as the ancestors of the Somalis were referred to by medieval Arab and ancient Greek geographers, respectively.[9][14][15][16]

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the populations south of the Sahara were divided into three broad ancestral groups: Hamites and Semites in the Horn of Africa and Sahel related to those in North Africa, who spoke languages belonging to the Afroasiatic family; Negroes in most of the rest of the subcontinent (hence, the toponym Black Africa for Africa south of the Sahara[17]), who spoke languages belonging to the Niger-Congo and Nilo-Saharan families; and Khoisan in Southern Africa, who spoke languages belonging to the Khoisan family.

The term "sub-Saharan" has been criticized by late Professor Herbert Ekwe-Ekwe,[18] on Pambazuka as being a racist word[19] because it refers to the area south of the Sahara by geographical conventions (as opposed to North Africa, which refers to a cardinal direction). Critics such as Professor Ekwe-Ekwe consider the term to imply a linguistic connotation of inferiority through its use of the prefix sub- (Latin for "under" or "below"; cf. sub-arctic), which they see as a linguistic vestige of European colonialism.[20][21]

Climate zones and ecoregions[]

Sub-Saharan Africa has a wide variety of climate zones or biomes. South Africa and the Democratic Republic of the Congo in particular are considered Megadiverse countries. It has a dry winter season and a wet summer season.

- The Sahel extends across all of Africa at a latitude of about 10° to 15° N. Countries that include parts of the Sahara Desert proper in their northern territories and parts of the Sahel in their southern region include Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Chad and Sudan. The Sahel has a hot semi-arid climate.

- South of the Sahel, a belt of savanna (the West and East Sudanian savannas) stretch from the Atlantic Ocean to the Ethiopian Highlands. The more humid Guinean and Northern Congolian forest-savanna mosaic lie between the savannas and the equatorial forests.

- The Horn of Africa includes hot desert climate along the coast but a hot semi-arid climate can be found much more in the interior, contrasting with savanna and moist broadleaf forests in the Ethiopian Highlands.

- Tropical Africa encompasses tropical rainforest stretching along the southern coast of West Africa and across most of Central Africa (the Congo) west of the African Great Lakes.

- In eastern Africa, woodlands, savannas, and grasslands are found in the equatorial zone, including the Serengeti ecosystem in Tanzania and Kenya.

- Distinctive Afromontane forests, grasslands, and shrublands are found in the high mountains and mountain ranges of eastern Africa, from the Ethiopian Highlands to South Africa.

- South of the equatorial forests, the Western and Southern Congolian forest-savanna mosaic are transition zones between the tropical forests and the miombo woodland belt that spans the continent from Angola to Mozambique and Tanzania.

- The Namib and Kalahari Deserts lie in south-western Africa, and are surrounded by semi-deserts including the Karoo western South Africa. The Bushveld grasslands lie to the east of the deserts.

- The Cape Floristic Region is at Africa's southern tip, and is home to diverse subtropical and temperate forests, woodlands, grasslands, and shrublands.

History[]

Prehistory[]

According to paleontology, early hominid skull anatomy was similar to that of their close cousins, the great African forest apes, gorilla and chimpanzee. However, they had adopted a bipedal locomotion and freed hands, giving them a crucial advantage enabling them to live in both forested areas and on the open savanna at a time when Africa was drying up, with savanna encroaching on forested areas. This occurred 10 million to 5 million years ago.[22]

By 3 million years ago several australopithecine hominid species had developed throughout southern, eastern and central Africa. They were tool users rather than tool manufacturers. The next major evolutionary step occurred around 2.3 million BCE, when primitive stone tools were used to scavenge the carcasses of animals killed by other predators, both for their meat and their marrow. In hunting, H. habilis was most likely not capable of competing with large predators and was more prey than hunter, although H. habilis probably did steal eggs from nests and may have been able to catch small game and weakened larger prey such as cubs and older animals. The tools were classed as Oldowan.[23]

Roughly 1.8 million years ago, Homo ergaster first appeared in the fossil record in Africa. From Homo ergaster, Homo erectus (upright man) evolved 1.5 million years ago. Some of the earlier representatives of this species were small-brained and used primitive stone tools, much like H. habilis. The brain later grew in size, and H. erectus eventually developed a more complex stone tool technology called the Acheulean. Potentially the first hominid to engage in hunting, H. erectus mastered the art of making fire. They were the first hominids to leave Africa, going on to colonize the entire Old World, and perhaps later on giving rise to Homo floresiensis. Although some recent writers suggest that H. georgicus, a H. habilis descendant, was the first and most primitive hominid to ever live outside Africa, many scientists consider H. georgicus to be an early and primitive member of the H. erectus species.[24]

The fossil and genetic evidence shows Homo sapiens developed in southern and eastern Africa by around 350,000 to 260,000 years ago.[25][26][27] and gradually migrated across the continent in waves. Between 50,000 and 60,000 years ago, their expansion out of Africa launched the colonization of the planet by modern humans. By 10,000 BCE, Homo sapiens had spread to all corners of the world. This dispersal of the human species is suggested by linguistic, cultural and genetic evidence.[23][28][29]

During the 11th millennium BP, pottery was independently invented in West Africa, with the earliest pottery there dating to about 9,400 BC from central Mali.[30] It spread throughout the Sahel and southern Sahara.[31]

After the Sahara became a desert, it did not present a totally impenetrable barrier for travelers between north and south because of the application of animal husbandry towards carrying water, food, and supplies across the desert. Prior to the introduction of the camel,[32] the use of oxen, mule, and horses for desert crossing was common, and trade routes followed chains of oases that were strung across the desert. The trans-saharan trade was in full motion by 500 BCE with Carthage being a major economic force for its establishment.[33][34][35] It is thought that the camel was first brought to Egypt after the Persian Empire conquered Egypt in 525 BCE, although large herds did not become common enough in North Africa for camels to be the pack animal of choice for the trans-saharan trade.[36]

West Africa[]

The Bantu expansion is a major migration movement that originated in West Central Africa (possibly around Cameroon) around 2500 BCE, reaching East and Central Africa by 1000 BCE and Southern Africa by the early centuries CE.

The Djenné-Djenno city-state flourished from 250 BCE to 900 CE and was influential to the development of the Ghana Empire.

The Nok culture of Nigeria (lasting from 1,500 BCE to 200 CE) is known from a type of terracotta figure.[37]

There were a number of medieval empires of the southern Sahara and the Sahel, based on trans-Saharan trade, including the Ghana Empire and the Mali Empire, Songhai Empire, the Kanem Empire and the subsequent Bornu Empire.[38] They built stone structures like in Tichit, but mainly constructed in adobe. The Great Mosque of Djenne is most reflective of Sahelian architecture and is the largest adobe building in the world.

In the forest zone, several states and empires such as Bono State, Akwamu and others emerged. The Ashanti Empire arose in the 18th century in modern-day Ghana.[39] The Kingdom of Nri, was established by the Igbo in the 11th century. Nri was famous for having a priest-king who wielded no military power. Nri was a rare African state which was a haven for freed slaves and outcasts who sought refuge in their territory. Other major states included the kingdoms of Ifẹ and Oyo in the western block of Nigeria which became prominent about 700–900 and 1400 respectively, and center of Yoruba culture. The Yoruba's built massive mud walls around their cities, the most famous being Sungbo's Eredo. Another prominent kingdom in southwestern Nigeria was the Kingdom of Benin 9th–11th century whose power lasted between the 15th and 19th century and was one of the greatest Empires of African history documented all over the world. Their dominance reached as far as the well-known city of Eko which was named Lagos by the Portuguese traders and other early European settlers. The Edo-speaking people of Benin are known for their famous bronze casting and rich coral, wealth, ancient science and technology and the Walls of Benin, which is the largest man-made structure in the world.

In the 18th century, the Oyo and the Aro confederacy were responsible for most of the slaves exported from modern-day Nigeria, selling them to European slave traders.[40] Following the Napoleonic Wars, the British expanded their influence into the Nigerian interior. In 1885, British claims to a West African sphere of influence received international recognition, and in the following year the Royal Niger Company was chartered under the leadership of Sir George Goldie. In 1900, the company's territory came under the control of the British government, which moved to consolidate its hold over the area of modern Nigeria. On 1 January 1901, Nigeria became a British protectorate as part of the British Empire, the foremost world power at the time. Nigeria was granted its independence in 1960 during the period of decolonization.

Central Africa[]

Archaeological finds in Central Africa provide evidence of human settlement that may date back over 10,000 years.[41] According to Zangato and Holl, there is evidence of iron-smelting in the Central African Republic and Cameroon that may date back to 3,000 to 2,500 BCE.[42] Extensive walled sites and settlements have recently been found in Zilum, Chad. The area is located approximately 60 km (37 mi) southwest of Lake Chad, and has been radiocarbon dated to the first millennium BCE.[43][44]

Trade and improved agricultural techniques supported more sophisticated societies, leading to the early civilizations of Sao, Kanem, Bornu, Shilluk, Baguirmi, and Wadai.[45]

Following the Bantu Migration into Central Africa, during the 14th century, the Luba Kingdom in southeast Congo came about under a king whose political authority derived from religious, spiritual legitimacy. The kingdom controlled agriculture and regional trade of salt and iron from the north and copper from the Zambian/Congo copper belt.[46]

Rival kingship factions which split from the Luba Kingdom later moved among the Lunda people, marrying into its elite and laying the foundation of the Lunda Empire in the 16th century. The ruling dynasty centralised authority among the Lunda under the Mwata Yamyo or Mwaant Yaav. The Mwata Yamyo's legitimacy, like that of the Luba king, came from being viewed as a spiritual religious guardian. This imperial cult or system of divine kings was spread to most of central Africa by rivals in kingship migrating and forming new states. Many new states received legitimacy by claiming descent from the Lunda dynasties.[46]

The Kingdom of Kongo existed from the Atlantic west to the Kwango river to the east. During the 15th century, the Bakongo farming community was united with its capital at M'banza-Kongo, under the king title, Manikongo.[46] Other significant states and peoples included the Kuba Kingdom, producers of the famous raffia cloth, the Eastern Lunda, Bemba, Burundi, Rwanda, and the Kingdom of Ndongo.

East Africa[]

Sudan[]

Nubia, covered by present-day northern Sudan and southern Egypt, was referred to as "Aethiopia" ("land of the burnt face") by the Greeks.[47]

Nubia in her greatest phase is considered sub-Saharan Africa's oldest urban civilisation. Nubia was a major source of gold for the ancient world. Nubians built famous structures and numerous pyramids. Sudan, the site of ancient Nubia, has more pyramids than anywhere else in the world.[48][better source needed]

Horn of Africa[]

The Axumite Empire spanned the southern Sahara, south Arabia and the Sahel along the western shore of the Red Sea. Located in northern Ethiopia and Eritrea, Aksum was deeply involved in the trade network between India and the Mediterranean. Growing from the proto-Aksumite Iron Age period (c. 4th century BCE), it rose to prominence by the 1st century CE. The Aksumites constructed monolithic stelae to cover the graves of their kings, such as King Ezana's Stele. The later Zagwe dynasty, established in the 12th century, built churches out of solid rock. These rock-hewn structures include the Church of St. George at Lalibela.

In ancient Somalia, city-states flourished such as Opone, Mosyllon and Malao that competed with the Sabaeans, Parthians and Axumites for the wealthy Indo–Greco–Roman trade.[49]

In the Middle Ages several powerful Somali empires dominated the region's trade, including the Ajuran Sultanate, which excelled in hydraulic engineering and fortress building,[50] the Sultanate of Adal, whose General Ahmed Gurey was the first African commander in history to use cannon warfare on the continent during Adal's conquest of the Ethiopian Empire,[51] and the Geledi Sultanate, whose military dominance forced governors of the Omani empire north of the city of Lamu to pay tribute to the Somali Sultan Ahmed Yusuf.[52][53][54]

Southeast Africa[]

According to the theory of recent African origin of modern humans, the mainstream position held within the scientific community, all humans originate from either Southeast Africa or the Horn of Africa.[55] During the first millennium CE, Nilotic and Bantu-speaking peoples moved into the region, and the latter now account for three-quarters of Kenya's population.

On the coastal section of Southeast Africa, a mixed Bantu community developed through contact with Muslim Arab and Persian traders, leading to the development of the mixed Arab, Persian and African Swahili City States.[56] The Swahili culture that emerged from these exchanges evinces many Arab and Islamic influences not seen in traditional Bantu culture, as do the many Afro-Arab members of the Bantu Swahili people. With its original speech community centered on the coastal parts of Tanzania (particularly Zanzibar) and Kenya – a seaboard referred to as the Swahili Coast – the Bantu Swahili language contains many Arabic loan-words as a consequence of these interactions.[57]

The earliest Bantu inhabitants of the Southeast coast of Kenya and Tanzania encountered by these later Arab and Persian settlers have been variously identified with the trading settlements of Rhapta, Azania and Menouthias[58] referenced in early Greek and Chinese writings from 50 CE to 500 CE,[59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66] ultimately giving rise to the name for Tanzania.[67][68] These early writings perhaps document the first wave of Bantu settlers to reach Southeast Africa during their migration.[69]

Between the 14th and 15th centuries, large medieval Southeast African kingdoms and states emerged, such as the Buganda,[70] Bunyoro and Karagwe[70] kingdoms of Uganda and Tanzania.

During the early 1960s, the Southeast African nations achieved independence from colonial rule.

Southern Africa[]

Settlements of Bantu-speaking peoples, who were iron-using agriculturists and herdsmen, were already present south of the Limpopo River by the 4th or 5th century displacing and absorbing the original Khoisan speakers. They slowly moved south, and the earliest ironworks in modern-day KwaZulu-Natal Province are believed to date from around 1050. The southernmost group was the Xhosa people, whose language incorporates certain linguistic traits from the earlier Khoisan inhabitants. They reached the Fish River in today's Eastern Cape Province.

Monomotapa was a medieval kingdom (c. 1250–1629), which existed between the Zambezi and Limpopo rivers of Southern Africa in the territory of modern-day Zimbabwe and Mozambique. Its old capital was located at Great Zimbabwe.

In 1487, Bartolomeu Dias became the first European to reach the southernmost tip of Africa. In 1652, a victualling station was established at the Cape of Good Hope by Jan van Riebeeck on behalf of the Dutch East India Company. For most of the 17th and 18th centuries, the slowly expanding settlement was a Dutch possession.

In 1795, the Dutch colony was captured by the British during the French Revolutionary Wars. The British intended to use Cape Town as a major port on the route to Australia and India. It was later returned to the Dutch in 1803, but soon afterward the Dutch East India Company declared bankruptcy, and the Dutch (now under French control) and the British found themselves at war again. The British captured the Dutch possession yet again at the Battle of Blaauwberg, commanded by Sir David Blair. The Zulu Kingdom was a Southern African tribal state in what is now KwaZulu-Natal in southeastern South Africa. The small kingdom gained world fame during and after their defeat in the Anglo-Zulu War. During the 1950s and early 1960s, most sub-Saharan African nations achieved independence from colonial rule.[71]

Historiographic and Conceptual Problems of North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa[]

Historiographic and Conceptual Problems[]

The current major problem in African studies that Mohamed (2010/2012)[72][73] identified is the inherited religious, Orientalist, colonial paradigm that European Africanists have preserved in present-day secularist, post-colonial, Anglophone African historiography.[72] African and African-American scholars also bear some responsibility in perpetuating this European Africanist preserved paradigm.[72]

Following conceptualizations of Africa developed by Leo Africanus and Hegel, European Africanists conceptually separated continental Africa into two racialized regions – Sub-Saharan Africa and North Africa.[72] Sub-Saharan Africa, as a racist geographic construction, serves as an objectified, compartmentalized region of “Africa proper”, “Africa noire,” or “Black Africa.”[72] The African diaspora is also considered to be a part of the same racialized construction as Sub-Saharan Africa.[72] North Africa serves as a racialized region of “European Africa”, which is conceptually disconnected from Sub-Saharan Africa, and conceptually connected to the Middle East, Asia, and the Islamic world.[72]

As a result of these racialized constructions and the conceptual separation of Africa, darker skinned North Africans, such as the so-called Haratin, who have long resided in the Maghreb, and do not reside south of Saharan Africa, have become analogically alienated from their indigeneity and historic reality in North Africa.[72] While the origin of the term “Haratin” remains speculative, the term may not date much earlier than the 18th century CE and has been involuntarily assigned to darker skinned Maghrebians.[72] Prior to the modern use of the term Haratin as an identifier, and utilized in contrast to bidan or bayd (white), sumr/asmar, suud/aswad, or sudan/sudani (black/brown) were Arabic terms utilized as identifiers for darker skinned Maghrebians before the modern period.[72] “Haratin” is considered to be an offensive term by the darker skinned Maghrebians it is intended to identify; for example, people in the southern region (e.g., Wad Noun, Draa) of Morocco consider it to be an offensive term.[72] Despite its historicity and etymology being questionable, European colonialists and European Africanists have used the term Haratin as identifiers for groups of “black” and apparently “mixed” people found in Algeria, Mauritania, and Morocco.[72]

The Saadian invasion of the Songhai Empire serves as the precursor to later narratives that grouped darker skinned Maghrebians together and identified their origins as being Sub-Saharan West Africa.[73] With gold serving as a motivation behind the Saadian invasion of the Songhai Empire, this made way for changes in latter behaviors toward dark-skinned Africans.[73] As a result of changing behaviors toward dark-skinned Africans, darker skinned Maghrebians were forcibly recruited into the army of Ismail Ibn Sharif as the Black Guard, based on the claim of them having descended from enslaved peoples from the times of the Saadian invasion.[73] Shurafa historians of the modern period would later utilize these events in narratives about the manumission of enslaved “Hartani” (a vague term, which, by merit of it needing further definition, is implicit evidence for its historicity being questionable).[73] The narratives derived from Shurafa historians would later become analogically incorporated into the Americanized narratives (e.g., the trans-Saharan slave trade, imported enslaved Sub-Saharan West Africans, darker skinned Magrebian freedmen) of the present-day European Africanist paradigm.[73]

As opposed to having been developed through field research, the analogy in the present-day European Africanist paradigm, which conceptually alienates, dehistoricizes, and denaturalizes darker skinned North Africans in North Africa and darker skinned Africans throughout the Islamic world at-large, is primarily rooted in an Americanized textual tradition inherited from 19th century European Christian abolitionists.[72] Consequently, reliable history, as opposed to an antiquated analogy-based history, for darker skinned North Africans and darker skinned Africans in the Islamic world are limited.[72] Part of the textual tradition generally associates an inherited status of servant with dark skin (e.g., Negro labor, Negro cultivators, Negroid slaves, freedman).[72] The European Africanist paradigm uses this as the primary reference point for its construction of origins narratives for darker skinned North Africans (e.g., imported slaves from Sub-Saharan West Africa).[72] With darker skinned North Africans or darker skinned Africans in the Islamic world treated as an allegory of alterity, another part of the textual tradition is the trans-Saharan slave trade and their presence in these regions are treated as that of an African diaspora in North Africa and the Islamic world.[72] Altogether, darker skinned North Africans (e.g., “black” and apparently “mixed” Maghrebians), darker skinned Africans in the Islamic world, the inherited status of servant associated with dark skin, and the trans-Saharan slave trade are conflated and modeled in analogy with African-Americans and the trans-Atlantic slave trade.[72]

The trans-Saharan slave trade has been used as a literary device in narratives that analogically explain the origins of darker skinned North Africans in North Africa and the Islamic world.[72] Caravans have been equated with slave ships, and the amount of forcibly enslaved Africans transported across the Sahara are alleged to be numerically comparable to the considerably large amount of forcibly enslaved Africans transported across the Atlantic Ocean.[72] The simulated narrative of comparable numbers is contradicted by the limited presence of darker skinned North Africans in the present-day Maghreb.[72] As part of this simulated narrative, post-classical Egypt has also been characterized as having plantations.[72] Another part of this simulated narrative is an Orientalist construction of hypersexualized Moors, concubines, and eunuchs.[72] Concubines in harems have been used as an explanatory bridge between the allegation of comparable numbers of forcibly enslaved Africans and the limited amount of present-day darker skinned Maghrebians who have been characterized as their diasporic descendants.[72] Eunuchs were characterized as sentinels who guarded these harems.[73] The simulated narrative is also based on the major assumption that the indigenous peoples of the Maghreb were once purely white Berbers, who then became biracialized through miscegenation with black concubines[72] (existing within a geographic racial binary of pale-skinned Moors residing further north, closer to the Mediterranean region, and dark-skinned Moors residing further south, closer to the Sahara).[73] The religious polemical narrative involving the suffering of enslaved European Christians of the Barbary slave trade has also been adapted to fit the simulated narrative of a comparable number of enslaved Africans being transported by Muslim slaver caravans, from the south of Saharan Africa, into North Africa and the Islamic world.[72]

Despite being an inherited part of the 19th century religious polemical narratives, the use of race in the secularist narrative of the present-day European Africanist paradigm has given the paradigm an appearance of possessing scientific quality.[73] The religious polemical narrative (e.g., holy cause, hostile neologisms) of 19th century European abolitionists about Africa and Africans are silenced, but still preserved, in the secularist narratives of the present-day European Africanist paradigm.[72] The Orientalist stereotyped hypersexuality of the Moors were viewed by 19th century European abolitionists as deriving from the Quran.[73] The reference to times prior, often used in concert with biblical references, by 19th century European abolitionists, may indicate that realities described of Moors may have been literary fabrications.[73] The purpose of these apparent literary fabrications may have been to affirm their view of the Bible as being greater than the Quran and to affirm the viewpoints held by the readers of their composed works.[73] The adoption of 19th century European abolitionists’ religious polemical narrative into the present-day European Africanist paradigm may have been due to its correspondence with the established textual tradition.[73] The use of stereotyped hypersexuality for Moors are what 19th century European abolitionists and the present-day European Africanist paradigm have in common.[73]

Due to a lack of considerable development in field research regarding enslavement in Islamic societies, this has resulted in the present-day European Africanist paradigm relying on unreliable estimates for the trans-Saharan slave trade.[73] However, insufficient data has also used as a justification for continued use of the faulty present-day European Africanist paradigm.[73] Darker skinned Maghrebians, particularly in Morocco, have grown weary of the lack of discretion foreign academics have shown toward them, bear resentment toward the way they have been depicted by foreign academics, and consequently, find the intended activities of foreign academics to be predictable.[73] Rather than continuing to rely on the faulty present-day European Africanist paradigm, Mohamed (2012) recommends revising and improving the current Africanist paradigm (e.g., critical inspection of the origins and introduction of the present characterization of the Saharan caravan; reconsideration of what makes the trans-Saharan slave trade, within its own context in Africa, distinct from the trans-Atlantic slave trade; realistic consideration of the experiences of darker-skinned Maghrebians within their own regional context).[73]

Conceptual Problems[]

Merolla (2017)[74] has indicated that the academic study of Sub-Saharan Africa and North Africa by Europeans developed with North Africa being conceptually subsumed within the Middle East and Arab world, whereas, the study of Sub-Saharan Africa was viewed as conceptually distinct from North Africa, and as its own region, viewed as inherently the same.[74] The common pattern of conceptual separation of continental Africa into two regions and the view of conceptual sameness within the region of Sub-Saharan Africa has continued until present-day.[74] Yet, with increasing exposure of this problem, discussion about the conceptual separation of Africa has begun to develop.[74]

The Sahara has served as a trans-regional zone for peoples in Africa.[74] Authors from various countries (e.g., Algeria, Cameroon, Sudan) in Africa have critiqued the conceptualization of the Sahara as a regional barrier, and provided counter-arguments supporting the interconnectedness of continental Africa; there are historic and cultural connections as well as trade between West Africa, North Africa, and East Africa (e.g., North Africa with Niger and Mali, North Africa with Tanzania and Sudan, major hubs of Islamic learning in Niger and Mali).[74] Africa has been conceptually compartmentalized into meaning “Black Africa”, “Africa South of the Sahara”, and “Sub-Saharan Africa.”[74] North Africa has been conceptually "Orientalized" and separated from Sub-Saharan Africa.[74] While its historic development has occurred within a longer time frame, the epistemic development (e.g., form, content) of the present-day racialized conceptual separation of Africa came as a result of the Berlin Conference and the Scramble for Africa.[74]

In African and Berber literary studies, scholarship has remained largely separate from one another.[74] The conceptual separation of Africa in these studies may be due to how editing policies of studies in the Anglophone and Francophone world are affected by the international politics of the Anglophone and Francophone world.[74] While studies in the Anglophone world have more clearly followed the trend of the conceptual separation of Africa, the Francophone world has been more nuanced, which may stem from imperial policies relating to French colonialism in North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa.[74] As the study of North Africa has largely been initiated by the Arabophone and Francophone world, denial of the Arabic language having become Africanized throughout the centuries it has been present in Africa has shown that the conceptual separation of Africa remains pervasive in the Francophone world; this denial may stem from historic development of the characterization of an Islamic Arabia existing as a diametric binary to Europe.[74] Among studies in the Francophone world, ties between North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa have been denied or downplayed, while the ties (e.g., religious, cultural) between the regions and peoples (e.g., Arab language and literature with Berber language and literature) of the Middle East and North Africa have been established by diminishing the differences between the two and selectively focusing on the similarities between the two.[74] In the Francophone world, construction of racialized regions, such as Black Africa (Sub-Saharan Africans) and White Africa (North Africans, e.g., Berbers and Arabs), has also developed.[74]

Despite having invoked and utilized identities in reference to the racialized conceptualizations of Africa (e.g., North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa) to oppose imposed identities, Berbers have invoked North African identity to oppose Arabized and Islamicized identities, and Sub-Saharan Africans (e.g., Negritude, Black Consciousness) and the African diaspora (e.g., Black is Beautiful) have invoked and utilized black identity to oppose colonialism and racism.[74] While Berber studies has largely sought to be establish ties between Berbers and North Africa with Arabs and the Middle East, Merolla (2017) indicated that efforts to establish ties between Berbers and North Africa with Sub-Saharan Africans and Sub-Saharan Africa have recently started to being undertaken.[74]

Demographics[]

Population[]

According to the 2019 revision of the World Population Prospects[75][76], the population of sub-Saharan Africa was 1.1 billion in 2019. The current growth rate is 2.3%. The UN predicts for the region a population between 2 and 2.5 billion by 2050[77] with a population density of 80 per km2 compared to 170 for Western Europe, 140 for Asia and 30 for the Americas.

Sub-Saharan African countries top the list of countries and territories by fertility rate with 40 of the highest 50, all with TFR greater than 4 in 2008. All are above the world average except South Africa and Seychelles.[78] More than 40% of the population in sub-Saharan countries is younger than 15 years old, as well as in Sudan, with the exception of South Africa.[79]

| Country | Population | Area (km2) | Literacy (M/F)[80] | GDP per Capita (PPP)[81] | Trans (Rank/Score)[82] | Life (Exp.)[80] | HDI | EODBR/SAB[83] | PFI (RANK/MARK) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18,498,000 | 1,246,700 | 82.9%/54.2% | 6,800 | 168/2 | 42.4 | 0.486 | 172/171 | 132/58,43 | |

| 8,988,091 | 27,830 | 67.3%/52.2% | 700 | 168/1.8 | 49 | 0.316 | 176/130 | 103/29,00 | |

| 68,692,542 | 2,345,410 | 80.9%/54.1% | 800 | 162/11.9 | 46.1 | 0.286 | 182/152 | 146/53,50 | |

| 18,879,301 | 475,440 | 77%/59.8% | 3,700 | 146/2.2 | 50.3 | 0.482 | 171/174 | 109/30,50 | |

| 4,511,488 | 622,984 | 64.8%/33.5% | 700 | 158/2.8 | 44.4 | 0.343 | 183/159 | 80/17,75 | |

| 10,329,208 | 1,284,000 | 40.8%/12.8% | 2,300 | 175/1.6 | 50.6 | 0.328 | 178/182 | 132/44,50 | |

| 3,700,000 | 342,000 | 90.5%/ 79.0% | 800 | 162/1.9 | 54.8 | 0.533 | N/A | 116/34,25 | |

| 1,110,000 | 28,051 | 93.4%/80.3% | 37,400 | 168/1.8 | 51.1 | 0.537 | 170/178 | 158/65,50 | |

| 1,514,993 | 267,667 | 88.5%/79.7% | 18,100 | 106/2.9 | 56.7 | 0.674 | 158/152 | 129/43,50 | |

| 39,002,772 | 582,650 | 77.7%/70.2 | 3,500 | 146/2.2 | 57.8 | 0.519 | 95/124 | 96/25,00 | |

| 174,507,539 | 923,768 | 84.4%/72.7%[84] | 5,900 | 136/2.7 | 57 | 0.504 | 131/120 | 112/34.24 | |

| 10,473,282 | 26,338 | 71.4%/59.8% | 2,100 | 89/3.3 | 46.8 | 0.429 | 67/11 | 157/64,67 | |

| 212,679 | 1,001 | 92.2%/77.9% | 3,200 | 111/2.8 | 65.2 | 0.509 | 180/140 | NA | |

| 44,928,923 | 945,087 | 77.5%/62.2% | 3,200 | 126/2.6 | 51.9 | 0.466 | 131/120 | NA/15,50 | |

| 32,369,558 | 236,040 | 76.8%/57.7 | 2,400 | 130/2.5 | 50.7 | 0.446 | 112/129 | 86/21,50 | |

| 31,894,000 | 1,886,068 | 79.6%/60.8% | 4,300 | 176/1.5 | 62.57[85] | 0.408 | 154/118 | 148/54,00 | |

| 8,260,490 | 619,745 | 1,600 | |||||||

| 516,055 | 23,000 | N/A | 3,600 | 111/2.8 | 54.5 | 0.430 | 163/177 | 110/31,00 | |

| 5,647,168 | 121,320 | N/A | 1,600 | 126/2.6 | 57.3 | 0.349 | 175/181 | 175/115,50 | |

| 85,237,338 | 1,127,127 | 50%/28.8% | 2,200 | 120/2.7 | 52.5 | 0.363 | 107/93 | 140/49,00 | |

| 9,832,017 | 637,657 | N/A | N/A | 180/1.1 | 47.7 | N/A | N/A | 164/77,50 | |

| 1,990,876 | 600,370 | 80.4%/81.8% | 17,000 | 37/5.6 | 49.8 | 0.633 | 45/83 | 62/15,50 | |

| 752,438 | 2,170 | N/A | 1,600 | 143/2.3 | 63.2 | 0.433 | 162/168 | 82/19,00 | |

| 2,130,819 | 30,355 | 73.7%/90.3% | 3,300 | 89/3.3 | 42.9 | 0.450 | 130/131 | 99/27,50 | |

| 19,625,000 | 587,041 | 76.5%/65.3% | 1,600 | 99/3.0 | 59 | 0.480 | 134/12 | 134/45,83 | |

| 14,268,711 | 118,480 | N/A | 1,200 | 89/3.3 | 47.6 | 0.400 | 132/128 | 62/15,50 | |

| 1,284,264 | 2,040 | 88.2%/80.5% | 22,300 | 42/5.4 | 73.2 | 0.728 | 17/10 | 51/14,00 | |

| 21,669,278 | 801,590 | N/A | 1,300 | 130/2.5 | 42.5 | 0.322 | 135/96 | 82/19,00 | |

| 2,108,665 | 825,418 | 86.8%/83.6% | 11,200 | 56/4.5 | 52.5 | 0.625 | 66/123 | 35/9,00 | |

| 87,476 | 455 | 91.4%/92.3% | 29,300 | 54/4.8 | 72.2 | 0.773 | 111/81 | 72/16,00 | |

| 59,899,991 | 1,219,912 | N/A | 13,600 | 55/4.7 | 50.7 | 0.619 | 34/67 | 33/8,50 | |

| 1,123,913 | 17,363 | 80.9%/78.3% | 11,089 | 79/3.6 | 40.8 | 0.608 | 115/158 | 144/52,50 | |

| 11,862,740 | 752,614 | N/A | 4,000 | 99/3.0 | 41.7 | 0.430 | 90/94 | 97/26,75 | |

| 11,392,629 | 390,580 | 92.7%/86.2% | 2,300 | 146/2.2 | 42.7 | 0.376 | 159/155 | 136/46,50 | |

| 8,791,832 | 112,620 | 47.9%/42.3% | 2,300 | 106/2.9 | 56.2 | 0.427 | 172/155 | 97/26,75 | |

| 12,666,987 | 1,240,000 | 32.7%/15.9% | 2,200 | 111/2.8 | 53.8 | 0.359 | 156/139 | 38/8,00 | |

| 15,730,977 | 274,200 | 25.3% | 1,900 | 79/3.6 | 51 | 0.331 | 150/116 | N/A | |

| 499,000 | 322,462 | 7,000 | |||||||

| 20,617,068 | 322,463 | 3,900 | |||||||

| 1,782,893 | 11,295 | 2,600 | |||||||

| 24,200,000 | 238,535 | 4,700 | |||||||

| 10,057,975 | 245,857 | 2,200 | |||||||

| 1,647,000 | 36,125 | 1,900 | |||||||

| 4,128,572 | 111,369 | 1,300 | |||||||

| 3,359,185 | 1,030,700 | 4,500 | |||||||

| 17,129,076 | 1,267,000 | 1,200 | |||||||

| 12,855,153 | 196,712 | 3,500 | |||||||

| 6,190,280 | 71,740 | 1,600 | |||||||

| 7,154,237 | 56,785 | 1,700 |

GDP per Capita (PPP) (2016, 2017 (PPP, US$)), Life (Exp.) (Life Expectancy 2006), Literacy (Male/Female 2006), Trans (Transparency 2009), HDI (Human Development Index), EODBR (Ease of Doing Business Rank June 2008 through May 2009), SAB (Starting a Business June 2008 through May 2009), PFI (Press Freedom Index 2009)

Languages and ethnic groups[]

Sub-Saharan Africa contains over 1,500 languages.

Afroasiatic[]

With the exception of the extinct Sumerian (a language isolate) of Mesopotamia, Afroasiatic has the oldest documented history of any language family in the world. Egyptian was recorded as early as 3200 BCE. The Semitic branch was recorded as early as 2900 BCE in the form of the Akkadian language of Mesopotamia (Assyria and Babylonia) and circa 2500 BCE in the form of the Eblaite language of north eastern Syria.[86]

The distribution of the Afroasiatic languages within Africa is principally concentrated in North Africa and the Horn of Africa. Languages belonging to the family's Berber branch are mainly spoken in the north, with its speech area extending into the Sahel (northern Mauritania, northern Mali, northern Niger).[87][88] The Cushitic branch of Afroasiatic is centered in the Horn, and is also spoken in the Nile Valley and parts of the African Great Lakes region. Additionally, the Semitic branch of the family, in the form of Arabic, is widely spoken in the parts of Africa that are within the Arab world. South Semitic languages are also spoken in parts of the Horn of Africa (Ethiopia, Eritrea). The Chadic branch is distributed in Central and West Africa.[89] Hausa, its most widely spoken language, serves as a lingua franca in West Africa (Niger, Ghana, Togo, Benin, Cameroon, and Chad).[90]

Khoisan[]

The several families lumped under the term Khoi-San include languages indigenous to Southern Africa and Tanzania, though some, such as the Khoi languages, appear to have moved to their current locations not long before the Bantu expansion.[91] In Southern Africa, their speakers are the Khoikhoi and San (Bushmen), in Southeast Africa, the Sandawe and Hadza.

Niger–Congo[]

The Niger–Congo family is the largest in the world in terms of the number of languages (1,436) it contains.[92] The vast majority of languages of this family are tonal such as Yoruba, and Igbo, However, others such as Fulani, Wolof and Kiswahili are not. A major branch of the Niger–Congo languages is Bantu, which covers a greater geographic area than the rest of the family. Bantu speakers represent the majority of inhabitants in southern, central and southeastern Africa, though San, Pygmy, and Nilotic groups, respectively, can also be found in those regions. Bantu-speakers can also be found in parts of Central Africa such as the Gabon, Equatorial Guinea and southern Cameroon. Swahili, a Bantu language with many Arabic, Persian and other Middle Eastern and South Asian loan words, developed as a lingua franca for trade between the different peoples in southeastern Africa. In the Kalahari Desert of Southern Africa, the distinct people known as Bushmen (also "San", closely related to, but distinct from "Hottentots") have long been present. The San evince unique physical traits, and are the indigenous people of southern Africa. Pygmies are the pre-Bantu indigenous peoples of Central Africa.

Nilo-Saharan[]

The Nilo-Saharan languages are concentrated in the upper parts of the Chari and Nile rivers of Central Africa and Southeast Africa. They are principally spoken by Nilotic peoples and are also spoken in Sudan among the Fur, Masalit, Nubian and Zaghawa peoples and in West and Central Africa among the Songhai, Zarma and Kanuri. The Old Nubian language is also a member of this family.

Major languages of Africa by region, family and number of primary language speakers in millions:

|

|

|

|

|

Genetic history[]

A 2017 archaeogenetic study of prehistoric fossils in sub-Saharan Africa observed a wide-ranging early presence of Khoisan populations in the region. Khoisan-related ancestry was inferred to have contributed to two thirds of the ancestry of hunter-gatherer populations inhabiting Malawi between 8,100 and 2,500 years ago and to one third of the ancestry of hunter gatherers inhabiting Tanzania as late as 1,400 years ago. Also in Tanzania, a pastoralist individual was found to carry ancestry related to the Western-Eurasian-related pre-pottery Levant farmers. These diverse early ancestries are believed to have been largely replaced after the Bantu expansion into central, eastern and southern Africa.[126]

A 2009 genetic clustering study, which genotyped 1327 polymorphic markers in various African populations, identified six ancestral clusters through Bayesian analysis and fourteen ancestral clusters through STRUCTURE[127] analysis within the continent. The clustering corresponded closely with ethnicity, culture and language.[128]

In addition, whole genome sequencing analysis of modern populations inhabiting sub-Saharan Africa has observed several primary inferred ancestry components: a Pygmy-related component carried by the Mbuti and Biaka Pygmies in Central Africa, a Khoisan-related component carried by Khoisan-speaking populations in Southern Africa, a Niger-Congo-related component carried by Niger-Congo-speaking populations throughout sub-Saharan Africa, a Nilo-Saharan-related component carried by Nilo-Saharan-speaking populations in the Nile Valley and African Great Lakes, and a West Eurasian-related component carried by Afroasiatic-speaking populations in the Horn of Africa and Nile Valley.[129][130]

According to a 2020 study by Durvasula et al., there are indications that 2% to 19% (or about ≃6.6 and ≃7.0%) of the DNA of four West African populations may have come from an unknown archaic hominin which split from the ancestor of humans and Neanderthals between 360 kya to 1.02 mya. However, the study also suggests that at least part of this archaic admixture is also present in Eurasians/non-Africans, and that the admixture event or events range from 0 to 124 ka B.P, which includes the period before the Out-of-Africa migration and prior to the African/Eurasian split (thus affecting in part the common ancestors of both Africans and Eurasians/non-Africans).[131][132][133]

A genome study (Busby et al. 2016) shows evidence for ancient migration from Eurasian populations and following admixture with native groups in several parts of sub-Saharan Africa.[134] Another study (Ramsay et al. 2018) also shows evidence of Eurasians in parts of sub-Saharan Africa, from both ancient and more recent migrations, ranging from 0% to 50%, varying by region, and generally highest in the Horn of Africa and parts of the Sahel zone.[135] "In addition to the intrinsic diversity within the continent due to population structure and isolation, migration of Eurasian populations into Africa has emerged as a critical contributor to the genetic diversity. These migrations involved the influx of different Eurasian populations at different times and to different parts of Africa. Comprehensive characterization of the details of these migrations through genetic studies on existing populations could help to explain the strong genetic differences between some geographically neighbouring populations.

This distinctive Eurasian admixture appears to have occurred over at least three time periods with ancient admixture in central west Africa (e.g. Yoruba from Nigeria) occurring between ∼7.5 and 10.5 kya, older admixture in east Africa (e.g. Ethiopia) occurring between ∼2.4 and 3.2 kya and more recent admixture between ∼0.15 and 1.5 kya in some east African (e.g. Kenyan) populations.

Subsequent studies based on LD decay and haplotype sharing in an extensive set of African and Eurasian populations confirmed the presence of Eurasian signatures in west, east and southern Africans. In the west, in addition to Niger-Congo speakers from The Gambia and Mali, the Mossi from Burkina Faso showed the oldest Eurasian admixture event ∼7 kya. In the east, these analyses inferred Eurasian admixture within the last 4000 years in Kenya.|author=Ramsay et al. 2018|title=African genetic diversity provides novel insights into evolutionary history and local adaptations." A 2014 genome study by Hodgson et al. indicated the Eurasian admixture in the Horn of Africa was from 23,000 years ago.[136][137] There is evidence that some Western Eurasian adnixture arrived in east Africa (particularly the Horn of Africa) in the Neolithic, with some moving south eventually reaching southern Africa.[138]

East Asian-related ancestry is commonly found in Madagascar and less in certain other regions of Africa, especially coastal regions of Eastern and Southern Africa. The presence of this East Asian-related ancestry is mostly linked to the Austronesian peoples expansion from Southeast Asia.[139][140][141][142] The peoples of Borneo were identified to resemble the East Asian voyagers, who arrived on Madagascar.[143][142]

It was also found that the Chinese mariner, explorer, diplomat, fleet admiral, and court eunuch during China's early Ming dynasty, Zheng He, and his many Chinese crew members, as well as some other stranded ships, contributed to the genetics of a local eastern African people as well as their culture.[144][145]

Major cities[]

Sub-Saharan Africa has several large cities. Lagos is a city in the Nigerian state of Lagos. The city, with its adjoining conurbation, is the most populous in Nigeria, and the second-most populous in Africa after Cairo, Egypt. It is one of the fastest-growing cities in the world,[146][147][148][149][150][151][152] and also one of the most populous urban agglomerations.[153][154] Lagos is a major financial centre in Africa; this megacity has the highest GDP,[155] and also houses Apapa, one of the largest and busiest ports on the continent.[156][157][158]

Dar es Salaam is the former capital of, as well as the most populous city in, Tanzania; it is a regionally important economic centre.[159] It is located on the Swahili coast.

Johannesburg is the largest city in South Africa. It is the provincial capital and largest city in Gauteng, which is the wealthiest province in South Africa.[160] While Johannesburg is not one of South Africa's three capital cities, it is the seat of the Constitutional Court. The city is located in the mineral-rich Witwatersrand range of hills, and is the centre of a large-scale gold and diamond trade.

Nairobi is the capital and the largest city of Kenya. The name comes from the Maasai phrase Enkare Nyrobi, which translates to "cool water", a reference to the Nairobi River which flows through the city. The city is popularly referred to as the Green City in the Sun.[161]

Other major cities in sub-Saharan Africa include Abidjan, Cape Town, Kinshasa, Luanda, Mogadishu and Addis Ababa.

List of Sub-Saharan Africa Capital Cities by Country[]

| COUNTRY | CAPITAL CITY |

|---|---|

| Angola | Luanda |

| Benin | Porto-Novo |

| Botswana | Gaborone |

| Burkina Faso | Ouagadougou |

| Burundi | Gitega |

| Cameroon | Yaounde |

| Central African Republic | Bangui |

| Chad | N'Djamena |

| Comoros | Moroni |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | Kinshasa |

| Republic of the Congo | Brazzaville |

| Cote d'Ivoire | Yamoussoukro |

| Djibouti | Djibouti |

| Equatorial Guinea | Malabo |

| Eritrea | Asmara |

| Eswatini | Mbabane |

| Ethiopia | Addis Ababa |

| Gabon | Libreville |

| Gambia | Banjul |

| Ghana | Accra |

| Guinea | Conakry |

| Guinea-Bissau | Bissau |

| Kenya | Nairobi |

| Lesotho | Maseru |

| Liberia | Monrovia |

| Madagascar | Antananarivo |

| Malawi | Lilongwe |

| Mali | Bamako |

| Mauritania | Nouakchott |

| Mauritius | Port Louis |

| Mozambique | Maputo |

| Namibia | Windhoek |

| Niger | Niamey |

| Nigeria | Abuja |

| Rwanda | Kigali |

| Sao Tome and Principe | Sao Tome |

| Senegal | Dakar |

| Seychelles | Victoria |

| Sierra Leone | Freetown |

| Somalia | Mogadishu |

| South Africa | Pretoria |

| South Sudan | Juba |

| Sudan | Khartoum |

| Tanzania | Dodoma |

| Togo | Lomé |

| Uganda | Kampala |

| Zambia | Lusaka |

| Zimbabwe | Harare |

Economy[]

This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: The most recent data in this section seems to be from 2015. (April 2021) |

In the mid-2010s, private capital flows to sub-Saharan Africa – primarily from the BRICs, private-sector investment portfolios, and remittances – began to exceed official development assistance.[162]

As of 2011, Africa is one of the fastest developing regions in the world. Six of the world's ten fastest-growing economies over the previous decade were situated below the Sahara, with the remaining four in East and Central Asia. Between 2011 and 2015, the economic growth rate of the average nation in Africa is expected to surpass that of the average nation in Asia. Sub-Saharan Africa is by then projected to contribute seven out of the ten fastest growing economies in the world.[163] According to the World Bank, the economic growth rate in the region had risen to 4.7% in 2013, with a rate of 5.2% forecasted for 2014. This continued rise was attributed to increasing investment in infrastructure and resources as well as steady expenditure per household.[164]

Energy and power[]

| Rank | Area | bb/day | Year | Like... |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| _ | W: World | 85540000 | 2007 est. | |

| 01 | E: Russia | 9980000 | 2007 est. | |

| 02 | Ar: Saudi Arb | 9200000 | 2008 est. | |

| 04 | As: Libya | 4725000 | 2008 est. | Iran |

| 10 | Af: Nigeria/Africa | 2352000 | 2011 est. | Norway |

| 15 | Af: Algeria | 2173000 | 2007 est. | |

| 16 | Af: Angola | 1910000 | 2008 est. | |

| 17 | Af: Egypt | 1845000 | 2007 est. | |

| 27 | Af: Tunisia | 664000 | 2007 est. | Australia |

| 31 | Af: Sudan | 466100 | 2007 est. | Ecuador |

| 33 | Af: Eq.Guinea | 368500 | 2007 est. | Vietnam |

| 38 | Af: DR Congo | 261000 | 2008 est. | |

| 39 | Af: Gabon | 243900 | 2007 est. | |

| 40 | Af: Sth Africa | 199100 | 2007 est. | |

| 45 | Af: Chad | 156000 | 2008 est. | Germany |

| 53 | Af: Cameroon | 87400 | 2008 est. | France |

| 56 | E: France | 71400 | 2007 | |

| 60 | Af: Ivory Coast | 54400 | 2008 est. | |

| _ | Af: Africa | 10780400 | 2011 | Russia |

| Source: CIA.gov, World Facts Book > Oil exporters. | ||||

As of 2009, 50% of Africa was rural with no access to electricity. Africa generates 47 GW of electricity, less than 0.6% of the global market share. Many countries are affected by power shortages.[165]

The percentage of residences with access to electricity in Sub-Saharan Africa is the lowest in the world. In some remote regions, fewer than one in every 20 households has electricity.[166][167][168]

Because of rising prices in commodities such as coal and oil, thermal sources of energy are proving to be too expensive for power generation. Sub-Saharan Africa is expected to build additional hydropower generation capacity of at least 20,165 MW by 2014. The region has the potential to generate 1,750 TWh of energy, of which only 7% has been explored. The failure to exploit its full energy potential is largely due to significant underinvestment, as at least four times as much (approximately $23 billion a year) and what is currently spent is invested in operating high cost power systems and not on expanding the infrastructure.[169]

African governments are taking advantage of the readily available water resources to broaden their energy mix. Hydro Turbine Markets in sub-Saharan Africa generated revenues of $120.0 million in 2007 and is estimated to reach $425.0 million.[when?] Asian countries, notably China, India, and Japan, are playing an active role in power projects across the African continent. The majority of these power projects are hydro-based because of China's vast experience in the construction of hydro-power projects and part of the Energy & Power Growth Partnership Services programme.[170]

With electrification numbers, Sub-Saharan Africa with access to the Sahara and being in the tropical zones has massive potential for solar photovoltaic electrical potential.[171] Six hundred million people could be served with electricity based on its photovoltaic potential.[172] China is promising to train 10,000 technicians from Africa and other developing countries in the use of solar energy technologies over the next five years. Training African technicians to use solar power is part of the China-Africa science and technology cooperation agreement signed by Chinese science minister Xu Guanhua and African counterparts during premier Wen Jiabao's visit to Ethiopia in December 2003.[173]

The New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD) is developing an integrated, continent-wide energy strategy. This has been funded by, amongst others, the African Development Bank (AfDB) and the EU-Africa Infrastructure Trust Fund. These projects must be sustainable, involve a cross-border dimension and/or have a regional impact, involve public and private capital, contribute to poverty alleviation and economic development, and involve at least one country in sub-Saharan Africa.[169]

Renewable Energy Performance Platform was established by the European Investment Bank the United Nations Environment Programme with a five-year goal of improving energy access for at least two million people in Sub-Saharan Africa. It has so far invested around $45 million to renewable energy projects in 13 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Solar power and hydropower are among the energy methods used in the projects.[174][175]

Media[]

Radio is the major source of information in sub-Saharan Africa.[176] Average coverage stands at more than a third of the population. Countries such as Gabon, Seychelles, and South Africa boast almost 100% penetration. Only five countries – Burundi, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Somalia – still have a penetration of less than 10%. Broadband penetration outside of South Africa has been limited where it is exorbitantly expensive.[177][178] Access to the internet via cell phones is on the rise.[179]

Television is the second major source of information.[176] Because of power shortages, the spread of television viewing has been limited. Eight percent have television, a total of 62 million. But those in the television industry view the region as an untapped green market. Digital television and pay for service are on the rise.[180]

Infrastructure[]

According to researchers at the Overseas Development Institute, the lack of infrastructure in many developing countries represents one of the most significant limitations to economic growth and achievement of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).[169][181][182] Less than 40% of rural Africans live within two kilometers of an all-season road, the lowest level of rural accessibility in the developing world. Spending on roads averages just below 2% of GDP with varying degree among countries. This compares with 1% of GDP that is typical in industrialised countries, and 2–3% of GDP found in fast-growing emerging economies. Although the level of expenditure is high relative to the size of Africa's economies, it remains small in absolute terms, with low-income countries spending an average of about US$7 per capita per year.[183] Infrastructure investments and maintenance can be very expensive, especially in such as areas as landlocked, rural and sparsely populated countries in Africa.[169]

Infrastructure investments contributed to Africa's growth, and increased investment is necessary to maintain growth and tackle poverty.[169][181][182] The returns to investment in infrastructure are very significant, with on average 30–40% returns for telecommunications (ICT) investments, over 40% for electricity generation and 80% for roads.[169]

In Africa, it is argued that in order to meet the MDGs by 2015 infrastructure investments would need to reach about 15% of GDP (around $93 billion a year).[169] Currently, the source of financing varies significantly across sectors.[169] Some sectors are dominated by state spending, others by overseas development aid (ODA) and yet others by private investors.[169] In sub-Saharan Africa, the state spends around $9.4 billion out of a total of $24.9 billion.[169] In irrigation, SSA states represent almost all spending; in transport and energy a majority of investment is state spending; in ICT and water supply and sanitation, the private sector represents the majority of capital expenditure.[169] Overall, aid, the private sector and non-OECD financiers between them exceed state spending.[169] The private sector spending alone equals state capital expenditure, though the majority is focused on ICT infrastructure investments.[169] External financing increased from $7 billion (2002) to $27 billion (2009). China, in particular, has emerged as an important investor.[169]

Oil and minerals[]

The region is a major exporter to the world of gold, uranium, chromium, vanadium, antimony, coltan, bauxite, iron ore, copper and manganese. South Africa is a major exporter of manganese[184] as well as chromium. A 2001 estimate is that 42% of the world's reserves of chromium may be found in South Africa.[185] South Africa is the largest producer of platinum, with 80% of the total world's annual mine production and 88% of the world's platinum reserve.[186] Sub-Saharan Africa produces 33% of the world's bauxite, with Guinea as the major supplier.[187] Zambia is a major producer of copper.[188] The Democratic Republic of Congo is a major source of coltan. Production from DR Congo is very small, but the country has 80% of the proven reserves in Africa, which are 80% of those worldwide.[189] Sub-saharan Africa is a major producer of gold, producing up to 30% of global production. Major suppliers are South Africa, Ghana, Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Guinea, and Mali. South Africa had been first in the world in terms of gold production since 1905, but in 2007 it moved to second place, according to GFMS, the precious metals consultancy.[190] Uranium is major commodity from the region. Significant suppliers are Niger, Namibia, and South Africa. Namibia was the number one supplier from sub-Saharan Africa in 2008.[191] The region produces 49% of the world's diamonds.

By 2015, it is estimated that 25% of North American oil will be from sub-Saharan Africa, ahead of the Middle East. Sub-Saharan Africa has been the focus of an intense race for oil by the West, China, India, and other emerging economies, even though it holds only 10% of proven oil reserves, less than the Middle East. This race has been referred to as the second Scramble for Africa. All reasons for this global scramble come from the reserves' economic benefits. Transportation cost is low and no pipelines have to be laid as in Central Asia. Almost all reserves are offshore, so political turmoil within the host country will not directly interfere with operations. Sub-Saharan oil is viscous, with a very low sulfur content. This quickens the refining process and effectively reduces costs. New sources of oil are being located in sub-Saharan Africa more frequently than anywhere else. Of all new sources of oil, ⅓ are in sub-Saharan Africa.[192]

Agriculture[]

Sub-Saharan Africa has more variety of grains than anywhere in the world. Between 13,000 and 11,000 BCE wild grains began to be collected as a source of food in the cataract region of the Nile, south of Egypt. The collecting of wild grains as source of food spread to Syria, parts of Turkey, and Iran by the eleventh millennium BCE. By the tenth and ninth millennia southwest Asians domesticated their wild grains, wheat, and barley after the notion of collecting wild grains spread from the Nile.[193]

Numerous crops have been domesticated in the region and spread to other parts of the world. These crops included sorghum, castor beans, coffee, cotton[194] okra, black-eyed peas, watermelon, gourd, and pearl millet. Other domesticated crops included teff, enset, African rice, yams, kola nuts, oil palm, and raffia palm.[193][195]

Domesticated animals include the guinea fowl and the donkey.

Agriculture represents 20% to 30% of GDP and 50% of exports. In some cases, 60% to 90% of the labor force are employed in agriculture.[196] Most agricultural activity is subsistence farming. This has made agricultural activity vulnerable to climate change and global warming. Biotechnology has been advocated to create high yield, pest and environmentally resistant crops in the hands of small farmers. The Bill and Melinda Gates foundation is a strong advocate and donor to this cause. Biotechnology and GM crops have met resistance both by natives and environmental groups.[197]

Cash crops include cotton, coffee, tea, cocoa, sugar, and tobacco.[198]

The OECD says Africa has the potential to become an agricultural superbloc if it can unlock the wealth of the savannahs by allowing farmers to use their land as collateral for credit.[199] There is such international interest in sub-Saharan agriculture, that the World Bank increased its financing of African agricultural programs to $1.3 billion in the 2011 fiscal year.[200] Recently, there has been a trend to purchase large tracts of land in sub-Sahara for agricultural use by developing countries.[181][182] Early in 2009, George Soros highlighted a new farmland buying frenzy caused by growing population, scarce water supplies and climate change. Chinese interests bought up large swathes of Senegal to supply it with sesame. Aggressive moves by China, South Korea and Gulf states to buy vast tracts of agricultural land in sub-Saharan Africa could soon be limited by a new global international protocol.[201]

Education[]

Forty percent of African scientists live in OECD countries, predominantly in Europe, the United States and Canada.[202] This has been described as an African brain drain.[203][204] According to Naledi Pandor, the South African Minister of Science and Technology, even with the drain enrollments in sub-Saharan African universities tripled between 1991 and 2005, expanding at an annual rate of 8.7%, which is one of the highest regional growth rates in the world.[citation needed] In the last 10 to 15 years interest in pursuing university-level degrees abroad has increased.[202]

According to the CIA, low global literacy rates are concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa, West Asia and South Asia. However, literacy rates in sub-Saharan Africa vary significantly between countries. The highest registered literacy rate in the region is in Zimbabwe (90.7%; 2003 est.), while the lowest literacy rate is in South Sudan (27%).[205]

Research on human capital formation was able to determine, that the numeracy levels of Sub-Saharan Africa and Africa, in general, were higher than numeracy levels in South Asia. In the 1940s more than 75% of the population of Sub-Saharan Africa was numerate. The numeracy of the West African countries, Benin and Ghana, was even higher with more than 80% of the population being numerate. In contrast, numeracy in South Asia was only around 50%.[206]

Sub-Saharan African countries spent an average of 0.3% of their GDP on science and technology on in 2007. This represents an increase from US$1.8 billion in 2002 to US$2.8 billion in 2007, a 50% increase in spending.[207][208]

Major progress in access to education[]

At the World Conference held in Jomtien, Thailand in 1990, delegates from 155 countries and representatives of some 150 organizations gathered with the goal to promote universal primary education and the radical reduction of illiteracy before the end of the decade. The World Education Forum, held ten years later in Dakar, Senegal, provided the opportunity to reiterate and reinforce these goals. This initiative contributed to having education made a priority of the Millennium Development Goals in 2000, with the aim of achieving universal schooling (MDG2) and eliminating gender disparities, especially in primary and secondary education (MDG3).[209] Since the World Education Forum in Dakar, considerable efforts have been made to respond to these demographic challenges in terms of education. The amount of funds raised has been decisive. Between 1999 and 2010, public spending on education as a percentage of gross national product (GNP) increased by 5% per year in sub-Saharan Africa, with major variations between countries, with percentages varying from 1.8% in Cameroon to over 6% in Burundi.[210] As of 2015, governments in sub-Saharan Africa spend on average 18% of their total budget on education, against 15% in the rest of the world.[209]

In the years immediately after the Dakar Forum, the efforts made by the African States towards achieving EFA produced multiple results in sub-Saharan Africa. The greatest advance was in access to primary education, which governments had made their absolute priority. The number of children in a primary school in sub-Saharan Africa thus rose from 82 million in 1999 to 136.4 million in 2011. In Niger, for example, the number of children entering school increased by more than three-and-a-half times between 1999 and 2011.[210] In Ethiopia, over the same period, over 8.5 million more children were admitted to primary school. The net rate of first-year access in sub-Saharan Africa has thus risen by 19 points in 12 years, from 58% in 1999 to 77% in 2011. Despite the considerable efforts, the latest available data from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics estimates that, for 2012, there were still 57.8 million children who were not in school. Of these, 29.6 million were in sub-Saharan Africa alone, a figure which has not changed for several years.[209] Many sub-Saharan countries have notably included the first year of secondary school in basic education. In Rwanda, the first year of secondary school was attached to primary education in 2009, which significantly increased the number of pupils enrolled at this level of education.[210][209] In 2012, the primary completion rate (PCR) – which measures the proportion of children reaching the final year of primary school – was 70%, meaning that more than three out of ten children entering primary school do not reach the final primary year.[209] Literacy rates have gone up in sub-Saharan Africa, and internet access has improved considerably. Nonetheless, a lot must yet happen for this world to catch up. The statistics show that the literacy rate for sub-Saharan Africa was 65% in 2017. In other words, one-third of the people aged 15 and above were unable to read and write. The comparative figure for 1984 was an illiteracy rate of 49%. In 2017, only about 22% of Africans were internet users at all, according to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU).[211]

Science and technology[]

Health[]

In 1987, the Bamako Initiative conference organized by the World Health Organization was held in Bamako, the capital of Mali, and helped reshape the health policy of sub-Saharan Africa.[212] The new strategy dramatically increased accessibility through community-based healthcare reform, resulting in more efficient and equitable provision of services.[213][self-published source?] A comprehensive approach strategy was extended to all areas of health care, with subsequent improvement in the health care indicators and improvement in health care efficiency and cost.[214][215]

In 2011, sub-Saharan Africa was home to 69% of all people living with HIV/AIDS worldwide.[216] In response, a number of initiatives have been launched to educate the public on HIV/AIDS. Among these are combination prevention programmes, considered to be the most effective initiative, the abstinence, be faithful, use a condom campaign, and the Desmond Tutu HIV Foundation's outreach programs.[217] According to a 2013 special report issued by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), the number of HIV positive people in Africa receiving anti-retro viral treatment in 2012 was over seven times the number receiving treatment in 2005, with an almost 1 million added in the last year alone.[218][219]:15 The number of AIDS-related deaths in sub-Saharan Africa in 2011 was 33 percent less than the number in 2005.[220] The number of new HIV infections in sub-Saharan Africa in 2011 was 25 percent less than the number in 2001.[220]

Life expectancy in sub-Saharan Africa increased from 40 years in 1960 to 61 years in 2017.[221]

Malaria is an endemic illness in sub-Saharan Africa, where the majority of malaria cases and deaths worldwide occur.[223] Routine immunization has been introduced in order to prevent measles.[224] Onchocerciasis ("river blindness"), a common cause of blindness, is also endemic to parts of the region. More than 99% of people affected by the illness worldwide live in 31 countries therein.[225] In response, the African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control (APOC) was launched in 1995 with the aim of controlling the disease.[225] Maternal mortality is another challenge, with more than half of maternal deaths in the world occurring in sub-Saharan Africa.[226] However, there has generally been progress here as well, as a number of countries in the region have halved their levels of maternal mortality since 1990.[226] Additionally, the African Union in July 2003 ratified the Maputo Protocol, which pledges to prohibit female genital mutilation (FGM).[227]

National health systems vary between countries. In Ghana, most health care is provided by the government and largely administered by the Ministry of Health and Ghana Health Services. The healthcare system has five levels of providers: health posts which are first-level primary care for rural areas, health centers and clinics, district hospitals, regional hospitals, and tertiary hospitals. These programs are funded by the government of Ghana, financial credits, Internally Generated Fund (IGF), and Donors-pooled Health Fund.[228]

Religion[]

Religion in Sub-Saharan Africa according to the Global Religious Landscape survey by the Pew Forum, 2012[229]

African countries below the Sahara are largely Christian, while those above the Sahara, in North Africa, are predominantly Islamic. There are also Muslim majorities in parts of the Horn of Africa (Djibouti and Somalia) and in the Sahel and Sudan regions (the Gambia, Sierra Leone, Guinea, Mali, Niger and Senegal), as well as significant Muslim communities in Ethiopia and Eritrea, and on the Swahili Coast (Tanzania and Kenya).[230] Mauritius is the only country in Africa to have a Hindu majority. In 2012, Sub-Saharan Africa constituted in absolute terms the third world's largest Christian population, after Europe and Latin America respectively.[229] In 2012, Sub-Saharan Africa also constitute in absolute terms the third world's largest Muslim population, after Asia and the Middle East and North Africa respectively.

Traditional African religions can be broken down into linguistic cultural groups, with common themes. Among Niger–Congo-speakers is a belief in a creator god or higher deity, along with ancestor spirits, territorial spirits, evil caused by human ill will and neglecting ancestor spirits, and priests of territorial spirits.[231][232][233][234] New world religions such as Santería, Vodun, and Candomblé, would be derived from this world. Among Nilo-Saharan speakers is the belief in Divinity; evil is caused by divine judgement and retribution; prophets as middlemen between Divinity and man. Among Afro-Asiatic-speakers is henotheism, the belief in one's own gods but accepting the existence of other gods; evil here is caused by malevolent spirits. The Semitic Abrahamic religion of Judaism is comparable to the latter world view.[235][231][236] San religion is non-theistic but a belief in a Spirit or Power of existence which can be tapped in a trance-dance; trance-healers.[237]

Generally, traditional African religions are united by an ancient complex animism and ancestor worship.[238]

Traditional religions in sub-Saharan Africa often display complex ontology, cosmology and metaphysics. Mythologies, for example, demonstrated the difficulty fathers of creation had in bringing about order from chaos. Order is what is right and natural and any deviation is chaos. Cosmology and ontology is also neither simple or linear. It defines duality, the material and immaterial, male and female, heaven and earth. Common principles of being and becoming are widespread: Among the Dogon, the principle of Amma (being) and Nummo (becoming), and among the Bambara, Pemba (being) and Faro (becoming).[239]

- West Africa

- Akan mythology

- Ashanti mythology (Ghana)

- Dahomey (Fon) mythology

- Efik mythology (Nigeria, Cameroon)

- Igbo mythology (Nigeria)

- Serer religion and Serer creation myth (Senegal, Gambia and Mauritania)

- Yoruba mythology (Nigeria, Benin)

- Central Africa

- Dinka mythology (South Sudan)

- Lotuko mythology (South Sudan)

- Bushongo mythology (Congo)

- Bambuti (Pygmy) mythology (Congo)

- Lugbara mythology (Congo)

- Southeast Africa

- Akamba mythology (eastern Kenya)

- Masai mythology (Kenya, Tanzania)

- Southern Africa

- Khoisan religion

- Lozi mythology (Zambia)

- Tumbuka mythology (Malawi)

- Zulu mythology (South Africa)

Sub-Saharan traditional divination systems display great sophistication. For example, the bamana sand divination uses well established symbolic codes that can be reproduced using four bits or marks. A binary system of one or two marks are combined. Random outcomes are generated using a fractal recursive process. It is analogous to a digital circuit but can be reproduced on any surface with one or two marks. This system is widespread in sub-Saharan Africa.[240][page needed]

Culture[]