Sunderland, Massachusetts

Sunderland, Massachusetts | |

|---|---|

First Congregational of Sunderland, organized in 1718 | |

Seal | |

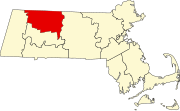

Location in Franklin County in Massachusetts | |

| Coordinates: 42°28′0″N 72°34′45″W / 42.46667°N 72.57917°WCoordinates: 42°28′0″N 72°34′45″W / 42.46667°N 72.57917°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Massachusetts |

| County | Franklin |

| Settled | 1713 |

| Incorporated | November 12, 1718 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Open town meeting |

| Area | |

| • Total | 14.7 sq mi (38.2 km2) |

| • Land | 14.2 sq mi (36.9 km2) |

| • Water | 0.5 sq mi (1.3 km2) |

| Elevation | 500 ft (152 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 3,684 |

| • Density | 250/sq mi (96/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP Code | 01375 |

| Area code(s) | 413 |

| FIPS code | 25-68400 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0618176 |

| Website | www |

Sunderland is a town in Franklin County, Massachusetts, United States, part of the Pioneer Valley. The population was 3,684 at the 2010 census.[1] It is part of the Springfield, Massachusetts Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Sunderland was first settled in 1713 and was officially incorporated in 1718. It was first known as Swampfield, a name which is now honored by Swampfield Road, but the name was changed to attract more residents. It was renamed in honor of Charles Spencer, the Earl of Sunderland.[2] Historically, the land was largely used for farming. Before the incorporation of Leverett in 1774, that town was a part of Sunderland's territory.

Geography and transportation[]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 14.7 square miles (38.2 km2), of which 14.2 square miles (36.9 km2) is land and 0.50 square miles (1.3 km2), or 3.53%, is water.[3] Sunderland is located in the Pioneer Valley on the east bank of the Connecticut River, which drains the town. Mount Toby, a prominent conglomerate mountain with a firetower lookout, stands at the east border of the town and is traversed by the 47-mile (76 km) Robert Frost Trail. The mountain, surrounded by Mount Toby State Forest, is known for its waterfalls, scenic vista, and biologically diverse ecosystem. Sunderland is home to the Buttonball Tree, an American sycamore famous for its size and age.

Sunderland lies on the southern edge of Franklin County, north of Hampshire County. Sunderland is bordered by Montague to the north, Leverett to the east, Amherst and Hadley to the south, and Whately and Deerfield to the west. (Because of the river, there is no direct access between Sunderland and Whately.) From its town center just east of the Connecticut River, Sunderland is 10 miles (16 km) south of the county seat of Greenfield, 28 miles (45 km) north of Springfield, and 90 miles (140 km) west of Boston. Most of the town's population lies in the western part of town, along the river, though there is a small village north of Mount Toby.

There is no interstate within town, with the nearest being Interstate 91 to the west of the town. Route 116 passes through the town, coming from Amherst and passing into Deerfield along the Sunderland Bridge. The bridge is the only road crossing of the Connecticut River between the General Pierce Bridge between Greenfield and Montague to the north, and the Calvin Coolidge Bridge between Hadley and Northampton to the south, a distance of 19 miles (31 km). Route 47 also passes through the western part of town, crossing Route 116 and heading north before terminating at Route 63 in Montague. Route 63 passes through the town for a short distance in the northeast corner of town. Alongside Route 63, the New England Central Railroad passes through the town, carrying the Amtrak Vermonter line through town towards Vermont. There is, however, no stop for the train within the town. The town is served by a route of the Franklin Regional Transit Authority (FRTA) bus line, between Amherst and Greenfield, and a route of the Pioneer Valley Transit Authority (PVTA) bus line, between Amherst and South Deerfield. The nearest general aviation airport is the Turners Falls Airport in Montague, with the nearest national air service being at Bradley International Airport in Connecticut.

Demographics[]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1840 | 698 | — |

| 1850 | 792 | +13.5% |

| 1860 | 839 | +5.9% |

| 1870 | 832 | −0.8% |

| 1880 | 755 | −9.3% |

| 1890 | 663 | −12.2% |

| 1900 | 771 | +16.3% |

| 1910 | 1,047 | +35.8% |

| 1920 | 1,289 | +23.1% |

| 1930 | 1,159 | −10.1% |

| 1940 | 1,085 | −6.4% |

| 1950 | 905 | −16.6% |

| 1960 | 1,279 | +41.3% |

| 1970 | 2,236 | +74.8% |

| 1980 | 2,929 | +31.0% |

| 1990 | 3,399 | +16.0% |

| 2000 | 3,777 | +11.1% |

| 2010 | 3,684 | −2.5% |

Source: United States census records and Population Estimates Program data.[4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13] | ||

|

|

As of the census[14] of 2000, there were 3,777 people, 1,633 households, and 765 families residing in the town. The population density was 262.5 people per square mile (101.3/km2). There were 1,668 housing units at an average density of 115.9 per square mile (44.8/km2). There were 1,633 households, out of which 22.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 37.5% were married couples living together, 6.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 53.1% were non-families. 27.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 4.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.28 and the average family size was 2.93.

The median income for a household in the town was $37,147, and the median income for a family was $53,021. Males had a median income of $36,779 versus $30,526 for females. The per capita income for the town was $20,024. About 4.2% of families and 14.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 5.8% of those under age 18 and none of those age 65 or over.

Government[]

In July 2009 at a high turnout election the town voted to not allow taxes to rise more than 2.5%. The vote was required by state law because towns are not allowed to raise taxes by more than 2.5% a year without voter approval. The town requested more money for education to ameliorate cuts in state funding because of the recession.[15][16] In 2009 the town adopted a 0.75% sales tax on meals and hotels, bringing the total including the state sales tax to 7%.[17]

Education[]

Sunderland is a member of the Frontier Regional and Union 38 School Districts, which also includes Conway, Whately and Deerfield. Each town operates its own elementary school, with Sunderland Elementary School serving the town's students from preschool through sixth grades. All four towns send seventh through twelfth grade students to Frontier Regional School in Deerfield. Frontier's athletics teams are nicknamed the Redhawks, and the team colors are red and blue. There are many art programs available during and after school at Frontier. There are several private schools in the area, including the Bement School (a coeducational boarding school serving students from kindergarten through ninth grades), the Eaglebrook School (a private boys' school for grades 6–9), and the Deerfield Academy, a private prep school.

Commerce[]

Sunderland boasts a Dunkin' Donuts, a Subway, seasonal businesses Smiarowski Cremey and Sugarloaf Frostie Cremey, multiple salons, a self-service laundry, a , a yoga studio, two liquor stores (Billy's Beverages and the Spirit Shoppe),and three convenience stores. There are several eateries, including Bubs BBQ, Dove's Nest Restaurant (serving breakfast and lunch) Frontier Pizza, Goten Steak House of Japan, Bridgeside Grille, Dimo's Restaurant, Wild Roots Cafe (offering organic breakfast and lunch), and the upscale Blue Heron Restaurant which is located at the site of the old town hall. All restaurants are located along Amherst Road (Rt. 116). Sunderland is also the home of the seasonal Mike's Maze Corn Maze.[18] Cooks Source magazine is based in Sunderland.[19]

Housing and development[]

The town makes use of an agricultural preservation restriction program. The development rights to farmland are bought up for 80% of the assessed value of the land. This allows farming to continue on the land but prevents residential and commercial development of the land.[20] Such actions have resulted in negative economic consequences, and this is something that economists are becoming increasingly concerned about.[21] According to the Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight, between 1980 and 2003, the nation's largest overall percentage increase in housing prices occurred in Massachusetts. The cost of rental housing has grown similarly. A recent study by the National Low Income Housing Coalition rated Massachusetts as being the least affordable state in which to rent an apartment in 2003.[22] The town, however, has a significant number of rental housing units that are home to many students from the neighboring colleges. These rental units are affordable to low and moderate income residents, but are not qualified as "affordable" under Chapter 40B, the state's stringent affordable housing law which requires deed restrictions to assure affordability in perpetuity. Sunderland has more rental units per capita than nearly every other municipality in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and the market rates of these units are lower than the vast majority of unit rates proposed in the proposed Sugarbush Meadows rental complex.

Sugarbush Meadows complex controversy[]

A new 150-rental unit development called Sugarbush Meadows complex has been proposed[when?] by Amherst developer Scott Nielsen. It would permanently designate 25 percent of its units for low-income or subsidized housing. Nielsen proposes to build the apartment complex off Plumtree Road.[23] The project is a 40B project, a state category covering low-income housing that encourages the building of "affordable" housing to help ameliorate Massachusetts' high cost of homes. The plan has been heavily resisted by the town after a series of very tense public meetings of the town's zoning board.[24]

In November 2009 an appeals hearing was held concerning the Sunderland Zoning Board of Appeal's rejection of the building application. The Housing Appeals Committee on June 21, 2010, overturned the decision and directed the zoning board to issue a comprehensive permit. It justified its decision by saying "One indication of the housing need in this case, however, is that only 0.4 % of the total housing in Sunderland is low and moderate income housing." This percentage reflects only the units with long-term deed restrictions under Chapter 40B, and discounts the reality that 51% of Sunderland's existing overall housing stock is affordable rental units.

Recreation[]

According to the 2007 Annual Report, upwards of 40 programs and events were made available to the residents of Sunderland through the support of the Recreation Department. Events and programs include craft lessons, UMass ice hockey and football events, adult and youth sports, an annual Easter Egg Hunt, hikes, dance lessons, and many other activities in Sunderland and the surrounding areas. The town holds annual fall festivals in mid-October and a Memorial Day parade and ceremony.[25]

The Mount Toby state reservation is on the northern edge of Sunderland, hosting a large trail network that is open to hiking, mountain biking, skiing, snowmobiling, and hunting. The Sunderland Boat Ramp on the Connecticut River allows for swimming, fishing, and boating.[26]

See also[]

- Pioneer Valley

- Massachusetts Comprehensive Permit Act: Chapter 40B

- Robert Frost Trail (Massachusetts)

References[]

- ^ "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (DP-1): Sunderland town, Franklin County, Massachusetts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 29, 2012.

- ^ [1], Sunderland, MA – Local Guide to the Town. Accessed April 20, 2009.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Sunderland town, Franklin County, Massachusetts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 29, 2012.

- ^ "Total Population (P1), 2010 Census Summary File 1". American FactFinder, All County Subdivisions within Massachusetts. United States Census Bureau. 2010.

- ^ "Massachusetts by Place and County Subdivision - GCT-T1. Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1990. Table 76: General Characteristics of Persons, Households, and Families: 1990. 1990 CP-1-23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1980 Census of the Population, Number of Inhabitants: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1981. Table 4. Populations of County Subdivisions: 1960 to 1980. PC80-1-A23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21-10 and 21-11, Massachusetts Table 6. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1930 to 1950. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1920 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. Number of Inhabitants, by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions. Pages 21-5 through 21-7. Massachusetts Table 2. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1920, 1910, and 1920. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1890 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. Pages 179 through 182. Massachusetts Table 5. Population of States and Territories by Minor Civil Divisions: 1880 and 1890. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1870 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1872. Pages 217 through 220. Table IX. Population of Minor Civil Divisions, &c. Massachusetts. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1860 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1864. Pages 220 through 226. State of Massachusetts Table No. 3. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1850 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1854. Pages 338 through 393. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ Barry, Stephanie (July 19, 2009). "Overrides fail in Sunderland". The Republican. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ^ Fred, Contrada (July 17, 2009). "Sunderland to vote on 2 Proposition 2.5 override questions". The Republican. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ^ Jim, Kinney (September 1, 2009). "First meal, hotel tax date passes". The Republican. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ^ Nelen, Mary (November 8, 2007). "Life Is a Cabaret – Blue Heron celebrates its tenth anniversary by bringing Moulin Rouge to Sunderland". The Valley Advocate. Retrieved December 27, 2007.

- ^ Crowley, Dan (November 10, 2010). Sunderland food magazine posts apology overuse of unauthorized material. Archived 2015-09-04 at the Wayback Machine Daily Hampshire Gazette

- ^ Town of Sunderland, MA Annual Report 2006,March 02, 2007

- ^ Feitshans, Ted; Mitch Renkow (March 2002). "Farmland Preservation: Law and Economics" (PDF). Agricultural and Resource Economics. North Carolina State University. Retrieved May 17, 2007.

- ^ "Winners and Losers in the Massachusetts Housing Market" (PDF). Citizens' Housing and Planning Association and the Massachusetts Housing Partnership. January 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 27, 2007. Retrieved May 17, 2007.

- ^ CRIS, CARL (November 16, 2007). "Sunderland board holds off on housing project; members indicate they are against it". The Daily Hampshire Gazette. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

- ^ CRIS, CARL Special to The Recorder (November 17, 2007). "Sunderland ZBA weighs in on 150-apt. complex". The Recorder (Greenfield). Retrieved December 20, 2007.

- ^ http://www.townofsunderland.us/Town%20of%20Sunderland%202007%20Annual%20Report%20(04.28.08).pdf

- ^ http://connecticutriver.us/site/content/connecticut-river-sunderland-boat-ramp

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sunderland, Massachusetts. |

External links[]

- Sunderland, Massachusetts

- Towns in Franklin County, Massachusetts

- Populated places established in 1713

- Springfield metropolitan area, Massachusetts

- Massachusetts populated places on the Connecticut River

- Towns in Massachusetts

- 1713 establishments in Massachusetts