Thai Chinese

This article may contain an excessive number of citations. (April 2020) |

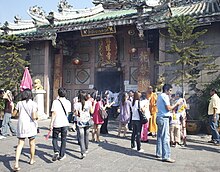

Wat Mangkon Kamalawat, a Chinese Buddhist temple in Thailand | |

| Total population | |

| c. 9,300,000 Approximately 14% of the Thai population | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Widespread in Thailand | |

| Languages | |

| Central Thai, Southwestern Mandarin, Malay, Southern Thai, Isan Lao, Lanna and Mandarin Chinese (dominant and supplementary) Teochew, Hokkien, Hainanese, Henghua, Cantonese, Hakka and Foochow (historical)[1] | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Theravada Buddhism Minorities Mahayana Buddhism, Christianity, Chinese folk religion and Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Thais Peranakans Overseas Chinese |

| Thai Chinese | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 華裔泰國人 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 华裔泰国人 | ||

| |||

Thai Chinese (also known as Chinese Thais, Sino-Thais; Thai: ชาวไทยเชื้อสายจีน, literally: Thais of Chinese origin) are Chinese descendants in Thailand. Thai Chinese are the largest minority group in the country and the largest overseas Chinese community in the world with a population of approximately 10 million people, accounting for 11–14% of the total population of the country as of 2012.[2][1][3] It is also the oldest and most prominent integrated overseas Chinese community. Slightly more than half of the ethnic Chinese population in Thailand trace their ancestry to Chaoshan. This is evidenced by the prevalence of the Teochew dialect among the Chinese community in Thailand as well as other Chinese languages.[4]:93The term as commonly understood signifies those whose ancestors immigrated to Thailand before 1949.

The Thai Chinese have been deeply ingrained into all elements of Thai society over the past 200 years. The present Thai royal family, the Chakri dynasty, was founded by King Rama I who himself was partly Chinese.[5] His predecessor, King Taksin of the Thonburi Kingdom, was the son of a Chinese father from Chaoshan.[6] With the successful integration of historic Chinese immigrant communities in Thailand, a significant number of Thai Chinese are the descendants of intermarriages between ethnic Chinese and native Thais. Many of these descendants have assimilated into Thai society and self-identify solely as Thai.[7][8][9]

Thai Chinese are a well-established middle class ethnic group and are well represented at all levels of Thai society.[10][11][12]:3, 43[13][14] They play a leading role in Thailand's business sector and dominate the Thai economy today.[15]:22[12]:179[16][17] In addition, Thai Chinese have a strong presence in Thailand's political scene with most of Thailand's former Prime Ministers and the majority of parliament having at least some Chinese ancestry.[18][19][15]:58[20] Thais of Chinese descent are also well represented among Thailand's military and royalist elite.[21][22]

Demographics[]

Thailand has the largest overseas Chinese community in the world outside Greater China.[23] 11 to 14 percent of Thailand's population are considered ethnic Chinese. The Thai linguist Theraphan Luangthongkum claim the share of those having at least partial Chinese ancestry at about 40 percent of the Thai population.[1]

Identity[]

For assimilated second and third generation descendants of Chinese immigrants, it is principally a personal choice whether or not to identify themselves as ethnic Chinese.[24] Nonetheless, nearly all Thai Chinese solely self-identify as Thai, due to their close integration and successful assimilation into Thai society.[25][26] G. William Skinner observed that the level of assimilation of the descendants of Chinese immigrants in Thailand disproved the "myth about the 'unchanging Chinese'", noting that "assimilation is considered complete when the immigrant's descendant identifies himself in almost all social situations as a Thai, speaks Thai language habitually and with native fluency, and interacts by choice with Thai more often than with Chinese."[27]:237 Skinner believed that the assimilation success of the Thai Chinese was a result of the wise policy of the Thai rulers who, since the 17th century, allowed able Chinese tradesmen to advance their ranks into the kingdom's nobility.[27]:240–241 The rapid and successful assimilation of the Thai Chinese has been celebrated by the Chinese descendants themselves, as evident in contemporary literature such as the novel Letters from Thailand (Thai: จดหมายจากเมืองไทย) by Botan.[28]

Today, the Thai Chinese constitute a significant part of the royalist/nationalist movements. When the then prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra, who is Thai Chinese, was ousted from power in 2006, it was Sondhi Limthongkul, another prominent Thai Chinese businessman, who formed and led People's Alliance for Democracy (PAD) movement to protest the successive governments run by Thaksin's allies.[29][30] Mr. Sondhi accused Mr. Thaksin of corruption based on improper business ties between Thaksin's corporate empire and the Singapore-based Temasek Holdings Group.[31] The Thai Chinese in and around Bangkok were also the main participants of the months-long political campaign against the government of Ms. Yingluck (Mr. Thaksin's sister), between November 2013 and May 2014, the event which culminated in the military takeover in May 2014.[32]

History[]

Traders from China began arriving in Ayutthaya by at least the 13th century. According to the Chronicles of Ayutthaya, Sanpet III (r. 1605–1610) had been "concerned solely with ways of enriching his treasury," and was "greatly inclined toward strangers and foreign nations".

When King Taksin, himself the son of a Chinese immigrant, ruled Thailand, King Taksin actively encouraged Chinese immigration and trade. Chinese setlers came to Siam in large numbers.[33] Immigration continued over the following years, and the Chinese population in Thailand jumped from 230,000 in 1825 to 792,000 by 1910. By 1932, approximately 12.2 percent of the population of Thailand was Chinese.[34]

The early Chinese immigration consisted almost entirely of men who did not bring women. Therefore, it became common for male Chinese immigrants to marry local Thai women. The children of such relationships were called Sino-Thai[35] or luk-jin (ลูกจีน) in Thai.[36] These Chinese-Thai intermarriages declined somewhat in the early 20th century, when significant numbers of Chinese women also began immigrating to Thailand.

Economic recession and unemployment forced many men to leave China for Thailand in search of work to seek wealth. If successful, they sent money back to their families in China. Many Chinese immigrants prospered under the "tax farming" system, whereby private individuals were sold the right to collect taxes at a price below the value of the tax revenues.

In the late 19th century, when Thailand was struggling to defend its independence from the colonial powers, Chinese bandits from Yunnan Province began making raids into the country in the Haw Wars (Thai: ปราบกบฏฮ่อ). Thai nationalist attitudes at all levels were thus colored by anti-Chinese sentiment. Members of the Chinese community had long dominated domestic commerce and had served as agents for royal trade monopolies. With the rise of European economic influence, however, many Chinese shifted to opium trafficking and tax collecting, both of which were despised occupations.

From 1882 to 1917, nearly 13,000 to 34,000 Chinese entered the country per year from southern China which was vulnerable to floods and drought, mostly settling in Bangkok and along the coast of the Gulf of Siam. They predominated in occupations requiring arduous labor, skills, or entrepreneurship. They worked as blacksmiths, railroad laborers and rickshaw pullers. While most Thais were engaged in rice production, the Chinese brought new farming ideas and new methods to supply labor on its rubber plantations, both domestically and internationally.[37] However, republican ideas brought by the Chinese were considered seditious by the Thai government. For example, a translation of Chinese revolutionary Sun Yat-sen's Three Principles of the People was banned under the Communism Act of 1933. The government had regulated Chinese schools even before compulsory education was established in the country, starting with the Private Schools Act of 1918. This act required all foreign teachers to pass a Thai language test and for principals of all schools to implement standards set by the Thai Ministry of Education.[38]

Legislation by King Rama VI (1910–1925) that required the adoption of Thai surnames was largely directed at the Chinese community as a number of ethnic Chinese families left Burma between 1930 and 1950 and settled in the Ratchaburi and Kanchanaburi Provinces of western Thailand. A few of the ethnic Chinese families in that area had already emigrated from Burma in the 19th century.

The Chinese in Thailand also suffered discrimination between the 1930s to 1950s under the military dictatorship of Prime Minister Plaek Phibunsongkhram (in spite of having part-Chinese ancestry himself),[39] which allied itself with the Empire of Japan. The Primary Education Act of 1932 made the Thai language the compulsory medium of education, but as a result of protests from Thai Chinese, by 1939, students were allowed two hours per week of Mandarin instruction.[38] State corporations took over commodities such as rice, tobacco, and petroleum and Chinese businesses found themselves subject to a range of new taxes and controls. By 1970, more than 90 percent of the Chinese born in Thailand had abandoned Chinese citizenship and were granted Thai citizenship instead. In 1975, diplomatic relations were established with China.[40]

Culture[]

Intermarriage with Thais has resulted in many people who claim Thai ethnicity with Chinese ancestry.[41] People of Chinese descent are concentrated in the coastal areas of Thailand, principally Bangkok.[42] Considerable segments of Thailand's academic, business, and political elites are of Chinese descent.[1]

Language[]

Today, nearly all ethnic Chinese in Thailand speak Thai exclusively. Only elderly Chinese immigrants still speak their native varieties of Chinese. The rapid and successful assimilation of Thai Chinese has been celebrated in contemporary literature such as "Letters from Thailand" (Thai: จดหมายจากเมืองไทย) by a Thai Chinese author Botan.[43] In the modern Thai language there are many signs of Chinese influence.[44] In the 2000 census, 231,350 people identified themselves as speakers of a variant of Chinese (Teochew, Hokkien, Hainanese, Cantonese, or Hakka).[1] The Teochew dialect has served as the language of Bangkok's influential Chinese merchants' circles since the foundation of the city in the 18th century. Although Chinese language schools were closed during the nationalist period before and during the Second World War, the Thai government never tried to suppress Chinese cultural expression. Today, businesses in Yaowarat Road and Charoen Krung Road in Bangkok's Samphanthawong District which constitute the city's "Chinatown" still feature bilingual signs in Chinese and Thai.[45] A number of Chinese words have found their way into the Thai language, especially the names of dishes and foodstuffs, as well as basic numbers (such as those from "three" to "ten") and terms related to gambling.[1] Chin Haw Chinese speak Southwestern Mandarin.

The rise of China's prominence on the global economic stage has prompted many Thai Chinese business families to see Mandarin as a beneficial asset in partaking in economic links and conducting business between Thailand and Mainland China, with some families encouraging their children to learn Mandarin in order to reap the benefits of their ethnic Chinese identity and the increasing role of Mandarin as a prominent language of Overseas Chinese business communities.[12]:184–185[15]:59[12]:179[46]:55 However, equally there are many Thais, regardless of their ethnic background who study Chinese in order to boost their business and career opportunities, rather than due to reasons of ethnic identity, with some sending their children to newly established Mandarin language schools.[12]:184–185

Rise to economic dominance[]

19th century[]

The British Raj agent John Crawfurd used detailed records kept from 1815 to 1824 to analyze the productivity of the 8,595 Chinese resident there vis-a-vis other ethnic groups. Astonished by their competence, he concluded that the Chinese population, about five-sixths of whom were unmarried men in the prime of life, "in point of effective labour, may be measured as equivalent to an ordinary population of above 37,000, and...to a numerical Malay population of more than 80,000!".[47]

By 1879, Chinese merchants controlled all steam-powered rice mills in Thailand. Most of the leading businessmen in Thailand were of Chinese extraction and accounted for a significant portion of Thailand's upper class.[37] In 1890, despite British shipping dominance in Bangkok, Chinese businesses oversaw 62 percent of the shipping sector and served as agents for Western shipping firms as well as their own.[37]:182–184 They also dominated the rubber industry, market gardening, sugar production, and fish exporting sectors. In Bangkok, Thai Chinese dominated the entertainment and media industries, being the pioneers of Thailand's early publishing houses, newspapers, and film studios.[18] Thai Chinese moneylenders wielded considerable economic power over the poorer indigenous Thai peasants, prompting accusations of Chinese bribery of government officials, wars between the Chinese secret societies, and the use of violent tactics to collect taxes. Chinese success served to foster Thai resentment against the Chinese at a time when their community was expanding rapidly. Waves of Han Chinese immigration swept into Siam in the 19th and early-20th centuries, peaking in the 1920s. Whereas Chinese bankers were accused of plunging the Thai peasant into poverty by charging high interest rates, the reality was that the Thai banking business was highly competitive. Chinese millers and rice traders were blamed for the economic recession that gripped Siam for nearly a decade after 1905.[37] By the end of the nineteenth century, the Chinese would lose control of foreign trade to the European colonial powers, but served as compradores for Western trading houses. Ethnic Chinese then moved into extractive industries—tin mining, logging and sawmilling, rice milling, as well as building ports and railways.[46]:48 While acknowledged for their industriousness, the Chinese in Thailand were scorned by many. In the late 19th century, a British official in Siam said that "the Chinese are the Jews of Siam ... by judicious use of their business faculties and their powers of combination, they hold the Siamese in the palm of their hand".[48]

20th century[]

By the early 20th century, the resident Chinese community in Bangkok was sizable, consisting of perhaps a third of the capital's population.[49] Anti-Chinese sentiment was rife.[12]:179–183 In 1914, the Thai nationalist King Vajiravudh (Rama VI), published a pamphlet in Thai and English—The Jews of the East— employing a pseudonym. In it, he lambasted the Chinese.[50] He described them as "avaricious barbarians who were 'entirely devoid of morals and mercy'".[48] He depicted successful Chinese businessmen as gaining their success at the expense of indigenous Thais, prompting some Thai politicians to blame Thai Chinese businessmen for Thailand's economic difficulties.[51] King Vajiravudh's views were influential among elite Thais and were quickly adopted by ordinary Thais, fueling their suspicion of and hostility to the Chinese minority.[12]:181–183 Wealth disparity and the poverty of native Thais resulted in blaming their socioeconomic ills on the Chinese, especially Chinese moneylenders. Beginning in the late-1930s and recommencing in the 1950s, the Thai government dealt with wealth disparities by pursuing a campaign of forced assimilation achieved through property confiscation, forced expropriation, coercive social policies, and anti-Chinese cultural suppression, seeking to eradicate ethnic Han Chinese consciousness and identity.[12]:183[15]:58 Thai Chinese became the targets of state discrimination while indigenous Thais were granted economic privileges.[12]:183–184[15]:57–58 The Siamese revolution of 1932 only tightened the grip of Thai nationalism, culminating in World War II when Thailand's Japanese ally was at war with China.[49]

Postwar Thailand was an agrarian economy hobbled by state-owned enterprises. The Chinese provided the impetus for Thailand's industrialization, transforming the Thai economy into an export-oriented, trade-based economy with global reach.[52]:261 Over the next several decades, internationalization and capitalist market-oriented policies led to the emergence of a manufacturing sector, which in turn catapulted Thailand into a Tiger Cub economy.[12]:35 Virtually all manufacturing and import-export firms were Chinese controlled.[12]:35[18] Despite their small numbers, the Chinese controlled virtually every line of business, from small retail trade to large industries. A mere ten percent of the population, ethnic Chinese dominate over four-fifths of the country's rice, tin, rubber, and timber exports, and virtually the country's entire wholesale and retail trade.[53] Virtually all new manufacturing establishments were Chinese controlled. Despite failed Thai affirmative action-based policies in the 1930s to economically empower the indigenous Thai majority, 70 percent of retail outlets and 80–90 percent of rice mills were controlled by ethnic Chinese.[12]:179[46]:55 A survey of Thailand's roughly seventy most powerful business groups found that all but three were owned by Thai Chinese.[12] Bangkok's Thai Chinese clan associations rose to prominence throughout the city as the clans are major property holders.[54]:193 The Chinese control more than 80 percent of public companies listed on the Stock Exchange of Thailand.[55][56] All the residential and commercial land in central Siam was owned by Thai Chinese.[12]:182 Fifty ethnic Chinese families controlled the country's entire business sectors equivalent to 81–90 percent of the overall market capitalization of the Thai economy.[57][58][8]:10[59][60][16]:15 Highly publicized profiles of wealthy Chinese entrepreneurs attracted great public interest and were used to illustrate the community's economic clout.[61] More than 80 percent of the top 40 richest people in Thailand are Thai of full or partial Chinese descent.[62] Thai Chinese entrepreneurs are influential in real estate, agriculture, banking, and finance, and the wholesale trading industries.[54]:193[63] In the 1990s, among the top ten Thai businesses in terms of sales, nine of them were Chinese-owned with only Siam Cement not being a Chinese-owned firm.[12]:179[46]:55 Of the five billionaires in Thailand in the late-20th century, all were ethnic Chinese or of partial Chinese descent.[64][15]:22[37] On 17 March 2012, Chaleo Yoovidhya, of Chinese origin, died while listed on Forbes list of billionaires as 205th in the world and third in the nation, with an estimated net worth of US$5 billion.[65]

By the late-1950s, ethnic Chinese comprised 70 percent of Bangkok's business owners and senior business managers, and 90 percent of the shares in Thai corporations were said to be held by Thais of Chinese extraction.[11][66][54] Ninety percent of Thailand's industrial and commercial capital are also held by ethnic Chinese.[67]:73 Ninety percent of all investments in the industry and commercial sector and at least 50 percent of all investments in the banking and finance sectors is controlled by ethnic Chinese.[68][16]:33[67][68] Economic advantages would also persist as Thai Chinese controlled 80–90 percent of the rice mills, the largest enterprises in the nation.[37] Thailand's lack of an indigenous Thai commercial culture in the private sector is dominated entirely by Thai Chinese themselves.[54]:193[58] Of the 25 leading entrepreneurs in the Thai business sector, 23 are ethnic Chinese or of partial Chinese descent. Thai Chinese also comprise 96 percent of Thailand's 70 most powerful business groups.[69][12]:35[70][71] Family firms are extremely common in the Thai business sector as they are passed down from one generation to the next.[72] Ninety percent of Thailand's manufacturing sector and 50 percent of Thailand's service sector is controlled by ethnic Chinese.[16] According to a Financial Statistics of the 500 Largest Public Companies in Asia Controlled by Overseas Chinese in 1994 chart released by Singaporean geographer Dr. Henry Yeung of the National University of Singapore, 39 companies were concentrated in Thailand with a market capitalization of US$35 billion and total assets of US$94 billion.[72] In Thailand, ethnic Chinese control the nation's largest private banks: Bangkok Bank, Thai Farmers Bank, Bank of Ayudhya.[64][16][54]:193[15]:22[73][74][54] Thai Chinese businesses are part of the larger bamboo network, a network of Overseas Chinese businesses operating in the markets of Southeast Asia that share common family, ethnic, language, and cultural ties.[75] Following the 1997 Asian financial crisis, structural reforms imposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) on Indonesia and Thailand led to the loss of many monopolistic positions long held by the ethnic Chinese business elite.[76] Despite the financial and economic crisis, Thai Chinese are estimated to own 65 percent of the total banking assets, 60 percent of the national trade, 90 percent of all local investments in the commercial sector, 90 percent of all local investments in the manufacturing sector, and 50 percent of all local investments in the banking and financial services sector.[68][77][78]

21st century[]

The early-21st century saw Thai Chinese dominate Thai commerce at every level of society.[79][12]:127, 179 Their economic clout plays a critical role in maintaining the country's economic vitality and prosperity.[46]:47–48 The economic power of the Thai Chinese is far greater than their proportion of the population would suggest.[12]:179[52]:277 With their powerful economic presence, the Chinese dominate the country's wealthy elite.[12]:179 Development policies imposed by the Thai government provided business opportunities for the ethnic Chinese. A distinct Sino-Thai business community has emerged as the dominant economic group, controlling virtually all the major business sectors across the country.[54]:193[67]:72 The modern Thai business sector is highly dependent on ethnic Chinese entrepreneurs and investors who control virtually all the country's banks and large conglomerates; their support is enhanced by the presence of lawmakers and politicians who are of at least part-Chinese descent.[18][73][12]:179 The Thai Chinese, a disproportionate wealthy, market-dominant minority not only form a distinct ethnic community, they also form, by and large, an economically advantaged social class.[12]:179–183[18][80][51][81][52]:261

With the rise of China as a global economic power, Thai-Chinese businesses have become the foremost, largest investors in Mainland China among all overseas Chinese communities worldwide.[12]:184 Many Thai Chinese have sent their children to newly established Chinese language schools, visit China in record numbers, invest in China, and assume Chinese surnames.[12]:184–185 The Charoen Pokphand (CP Group), a prominent Thai conglomerate founded by the Thai-Chinese Chearavanont family, has been the single largest foreign investor in China.[12]:41, 179[46]:55[82] CP Group also owns and operates Tesco Lotus, one of the largest foreign hypermarkets, 74 stores and seven distribution centers in 30 cities across China.[82]

According to Thai historian, Dr. Wasana Wongsurawat, the Thai elite has remained in power by employing a simple two-part strategy: first, secure the economic base by cultivating the support of the Thai-Chinese business elites; second, align with the dominant world power of the day. As of 2020, increasingly, that power is China.[49]

Religion[]

First-generation Chinese immigrants were followers of Mahayana Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism. Theravada Buddhism has since become the religion of many ethnic Chinese in Thailand, especially among assimilated Chinese. Many Chinese in Thailand commonly combine certain practices of Chinese folk religion with Theravada Buddhism due to the openness and tolerance of Buddhism.[83] Major Chinese festivals such as Chinese New Year, Mid-Autumn Festival and Qingming are widely celebrated, especially in Bangkok, Phuket, and other parts of Thailand where there are large Chinese populations.[84] There are several prominent Buddhist monks with Chinese ancestry like the well-known Buddhist reformer, Buddhadasa Bhikkhu and the former abbot of Wat Saket, Somdet Kiaw.

The Peranakans in Phuket are noted for their nine-day vegetarian festival between September and October. During the festival period, devotees will abstain from meat and the Chinese mediums will perform mortification of the flesh to exhibit the power of the Deities, and the rites and rituals seen are devoted to the veneration of various Deities. Such idiosyncratic traditions were developed during the 19th century in Phuket by the local Chinese with influences from Thai culture.[85]

In the north, there is a small minority of Chinese people who traditionally practice Islam. They belong to a group of Chinese people, known as Chin Ho. Most of the Chinese Muslims are descended from Hui people who live in Yunnan, China. There are seven Chinese mosques in Chiang Mai.[86] The best known is the Ban Ho Mosque.

Dialect groups[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2020) |

The vast majority of Thai Chinese belong to various southern Chinese dialect groups. Of these, 56 percent are Teochew (also commonly spelled as Teochiu), 16 percent Hakka and 11 percent Hainanese. The Cantonese and Hokkien each constitute seven percent of the Chinese population, and three percent belong to other Chinese dialect groups.[87] A large number of Thai Chinese are the descendants of intermarriages between Chinese immigrants and Thais, while there are others who are of predominantly or solely of Chinese descent. People who are of mainly Chinese descent are descendants of immigrants who relocated to Thailand as well as other parts of Nanyang (the Chinese term for Southeast Asia used at the time) in the early to mid-20th century due to famine and civil war in the southern Chinese provinces of Guangdong (Teochew, Cantonese, and Hakka groups), Hainan (Hainanese), and Fujian (Hokkien, Henghua, Hockchew and Hakka groups).

Teochew[]

The Teochews mainly settled near the Chao Phraya River in Bangkok. Many of military commanders as well as billionaries and politicians are ethnically Chinese from a Teochew background, while others were involved in trade. During the reign of King Taksin, some influential Teochew traders were granted certain privileges. These prominent traders were called "royal Chinese" (Jin-luang or จีนหลวง in Thai).

Hakka[]

Hakkas are mainly concentrated in Chiang Mai, Phuket and central western provinces. The Hakka own many private banks in Thailand, notably Kasikorn Bank and Kiatnakin Bank.

Hokkien[]

The Hokkiens are a dominant group of Chinese particularly in the south of Thailand; they primarily live in Trang Province and Phuket Province, respectively. A smaller Hokkien community can also be found in Hatyai in Songkhla Province.

Hainanese[]

The Hainanese comprises another prominent Thai Chinese group which are mainly concentrated in Bangkok, Samui and some central provinces of the country. Notable Hainanese Thai families includes the Chirathivat family of Central Group and Yoovidhya family of Krating Daeng. Several Thai politicians are also of Hainanese descent, such as Sondhi Limthongkul, Boonchu Rojanastien and Pote Sarasin.

Peranakan[]

A subethnic Chinese group of mostly Hoklo descent and are mostly concentrated in the southern parts of their country just like their unmixed fellow dialect folk of Hokkien origins (having shared a common ancestral home back in Fujian province), but over time they have been completely assimilated with a blending pot of different cultures and races into their bloodline after generations of births. As a matter of fact, some ethnic Chinese living in the Malay-dominated provinces in the far south use Malay, rather than Thai as a lingua franca and many have intermarried with local Malays that resulted them to being converted into Islam after marriage (in which they are a contributor of the minority Muslim populace of the Chinese minority, the other being the unmxied Chin Haw subgroup in the northern part).[88]:14–15

Cantonese[]

The Cantonese are not very prominent but are mainly concentrated in Bangkok and the central provinces. Most of them trace their ancestry to Taishan (臺山), Xinhui (新會) and Guangzhou (廣州) prefectures of Guangdong province in Mainland China. One of the largest construction companies, Sino-Thai Engineering & Construction Public Company Limited, in Thailand is run by a Thai Cantonese family founded in 1962 by Chavarat Charnvirakul (陳景鎮). His son, Anutin Charnvirakul, is the current Minister for Public Health in Thailand. The well-known Farm Chokchai and the Chokchai milk brand in Thailand are owned by an ethnic Chinese family of Cantonese ancestry, the Bulakul family.

Hokchew[]

A dialect group belonging to the Min-speaking family of dialects with ancestry from the cities of Fuzhou and Ningde in Fujian province of China, they are the smallest ethnolinguistic dialect subgroup of Thailand's ethnic Chinese and are mostly found in the southern coastal provinces of Nakhon Si Thammarat and Chumphon in settlements such as Chandi and Lamae.

Family Names[]

Almost all Thai-Chinese or Sino-Thais, especially those who came to Thailand before the 1950s, only use Thai surname in public, while it was required by Rama VI as a condition of Thai citizenship. The few retaining native Chinese surnames are either recent immigrants or resident aliens. For some immigrants who settled in Southern Thailand before the 1950s, it was common to simply prefix Sae- (from Chinese: 姓, 'family name') to a transliteration of their name to form the new family name; Wanlop Sae-Chio's last name thus derived from the Hainanese 周 and Chanin Sae-ear's last name is from Hokkien 楊. Sae is also used by Hmong people in Thailand. In 1950s-1970s Chinese immigrants had that surname in Thailand, although Chinese immigrants to Thailand after the 1970s use their Chinese family names without Sae- therefore these people didn't recognize as Sino-Thais like Thai celebrity, Thassapak Hsu's last name is Mandarin's surname 徐.

Sino-Thai surnames are often distinct from those of the other-Thai population, with generally longer names mimicking those of high officials and upper-class Thais[89] and with elements of these longer names retaining their original Chinese family name in translation or transliteration. For example, former Prime Minister Banharn Silpa-Archa's unusual Archa element is a translation into Thai of his family's former name Ma (trad. 馬, simp. 马, lit. 'horse'). Similarly, the Lim in Sondhi Limthongkul's name is the Hainanese pronunciation of the name Lin (林). For an example, see the background of the Vejjajiva Palace name.[90] Note that the latter-day Royal Thai General System of Transcription would transcribe it as Wetchachiwa and that the Sanskrit-derived name refers to 'medical profession'.

Notable figures[]

Prime Ministers of Chinese descent[]

Kon Hutasingha |  Thawan Thamrongnawasawat |  Chatichai Choonhavan |

Chuan Leekpai |  Banharn Silpa-archa |  Yingluck Shinawatra |

20th century[]

Kon Hutasingha,[91] Phot Phahonyothin,[92][93] Plaek Phibunsongkhram,[94] Seni Pramoj,[95] Pridi Banomyong,[96][97] Thawan Thamrongnawasawat,[98][99] Pote Sarasin,[100] Thanom Kittikachorn,[101] Sarit Thanarat,[102][103][104] Kukrit Pramoj,[95] Thanin Kraivichien,[105] Kriangsak Chamanan,[106] Chatichai Choonhavan,[107][108] Anand Panyarachun,[109][110] Suchinda Kraprayoon,[111][112][113] Chuan Leekpai,[4][114] Banharn Silpa-archa,[115] Chavalit Yongchaiyudh.[116]

21st century[]

Thaksin Shinawatra,[117] Samak Sundaravej.[118], Yingluck Shinawatra,[117] Abhisit Vejjajiva,[119][120][121] Prayut Chan-o-cha.[122][123]

Deputy and ministerial holders[]

- Boonchu Rojanastien, Banker, Deputy Prime Minister of Thailand and Finance Minister.

- Chitchai Wannasathit, Acting Prime Minister of Thailand.

- Pao Sarasin, Deputy Prime Minister and Interior Minister.

- Chavarat Charnvirakul, Acting Prime Minister of Thailand, Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Social Development and Human Security and Interior Minister.

- Anutin Charnvirakul, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Public Health.

Businessmen[]

- Chin Sophonpanich, Banker and founder of Bangkok Bank and Bangkok Insurance.

- Chaleo Yoovidhya, Billionaire inventor of Red Bull.

- Vanich Chaiyawan, Billionaire and chairman of Thai Life Insurance, the second-largest life insurer in Thailand.

- Dhanin Chearavanont, Billionaire and the senior chairman of CP Group.

- Krit Ratanarak, Billionaire and the chairman of Bangkok Broadcasting & Television Company.

- Charoen Sirivadhanabhakdi, Billionaire business magnate and investor.

- Chalerm Yoovidhya, Bilionaire Businessman and heir to the Red Bull fortune.

- Vichai Srivaddhanaprabha, Billionaire founder, owner and chairman of King Power.

- Aiyawatt Srivaddhanaprabha, youngest billionaire in Asia.

- Panthongtae Shinawatra, billionaire.

Others[]

- Chang and Eng Bunker, famous conjoined twins.

- Apichatpong Weerasethakul, film director.

- Bundit Ungrangsee, symphonic conductor.

- Joey Boy, hip hop singer and producer.

- Tanutchai Wijitwongthong, actor.

- Chalida Vijitvongthong, actress.

- Ten (singer), singer and dancer.

See also[]

- Kian Un Keng Shrine (建安宮)

- Wat Mangkon Kamalawat (龍蓮寺)

- Wat Bamphen Chin Phrot (永福寺)

- Leng Buai Ia Shrine

- Gong Wu Shrine

- San Chaopho Suea (Sao Chingcha) (打惱路玄天上帝廟)

- Wat San Chao Chet (七聖媽廟)

- Chao Mae Thapthim Shrine (水尾聖娘廟)

- Thian Fah Foundation Hospital (天華醫院)

- Poh Teck Tung Foundation

- Lim Ko Niao (林姑娘)

- Chow Yam-nam (White Dragon King)

- Chinese folk religion in Southeast Asia

- Burmese Chinese

- Laotian Chinese

- Cambodian Chinese

- Vietnamese Chinese

- Malaysian Chinese

- Singaporean Chinese

- Indonesian Chinese

- Bruneian Chinese

- Filipino Chinese

- China–Thailand relations

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Luangthongkum, Theraphan (2007). "The Position of Non-Thai Languages in Thailand". In Guan, Lee Hock; Suryadinata, Leo Suryadinata (eds.). Language, Nation and Development in Southeast Asia. ISEAS Publishing. p. 191. ISBN 9789812304827 – via Google Books.

- ^ John Draper; Joel Sawat Selway (January 2019). "A New Dataset on Horizontal Structural Ethnic Inequalities in Thailand in Order to Address Sustainable Development Goal 10". Social Indicators Research. 141 (4): 280. doi:10.1007/s11205-019-02065-4. S2CID 149845432. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ Barbara A. West (2009), Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania, Facts on File, p. 794, ISBN 978-1438119137 – via Google Books

- ^ Jump up to: a b Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2009). A History of Thailand (2nd, paper ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521759151.

- ^ Reid, Anthony (2015). A History of Southeast Asia: Critical Crossroads. p. 215. ISBN 9780631179610.

- ^ Woodside 1971, p. 8.

- ^ Jiangtao, Shi (16 October 2016). "Time of uncertainty lies ahead for Bangkok's ethnic Chinese". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gambe, Annabelle (2000). Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurship and Capitalist Development in Southeast Asia. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0312234966.

- ^ Chaloemtiarana, Thak (25 December 2014). "Are We Them? Textual and Literary Representations of the Chinese in Twentieth-Century Thailand". Southeast Asian Studies. 3 (3). Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ A. B. Susanto; Susa, Patricia (2013). The Dragon Network: Inside Stories of the Most Successful Chinese Family. Wiley. ISBN 9781118339404. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Choosing Coalition Partners: The Politics of Central Bank Independence in ... - Young Hark Byun, The University of Texas at Austin. Government - Google Books. 2006. ISBN 9780549392392. Retrieved 23 April 2012.[dead link]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Chua, Amy (2003). World on Fire: How Exporting Free Market Democracy Breeds Ethnic Hatred and Global Instability (Paperback). Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-72186-8. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ Vatikiotis, Michael; Daorueng, Prangtip (12 February 1998). "Entrepreneurs" (PDF). Far Eastern Economic Review. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "High technology and globalization challenges facing overseas Chinese entrepreneurs | SAM Advanced Management Journal". Find Articles. Retrieved 23 April 2012.[not specific enough to verify]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Chua, Amy L. (1 January 1998). "Markets, Democracy, and Ethnicity: Toward A New Paradigm For Law and Development". The Yale Law Journal. 108 (1): 58. doi:10.2307/797471. JSTOR 797471.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Yeung, Henry Wai-Chung (2005). Chinese Capitalism in a Global Era: Towards a Hybrid Capitalism. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415309899.

- ^ World and Its Peoples: Eastern and Southern Asia - Marshall Cavendish Corporation, Not Available (NA) - Google Books. 1 September 2007. ISBN 9780761476313. Retrieved 23 April 2012.[not specific enough to verify]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Kolodko, Grzegorz W. (2005). Globalization And Social Stress. Hauppauge NY: Nova Science Publishers. p. 171. ISBN 9781594541940. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Marshall, Tyler (17 June 2006). "Southeast Asia's new best friend". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ^ Songkünnatham, Peera (30 June 2018). "Betraying my heritage: the riddles of Chinese and Lao". The Isaan Record. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Smith, Anthony (1 February 2005). "Thailand's Security and the Sino-Thai Relationship". China Brief. 5 (3). Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Jiangtao, Shi (14 October 2016). "In Bangkok's Chinatown, grief and gratitude following Thai king's death". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ "Chinese Diaspora Across the World: A General Overview". Academy for Cultural Diplomacy.

- ^ Peleggi, Maurizio (2007). "Thailand: The Worldly Kingdom". Reaktion Books: 46. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Paul Richard Kuehn, Who Are The Thai-Chinese And What Is Their Contribution to Thailand?

- ^ Skinner, G. William (1957). "Chinese Assimilation and Thai Politics". The Journal of Asian Studies. 16 (2): 237–250. doi:10.2307/2941381. JSTOR 2941381.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Skinner, G, William (c. 1957). Chinese Society in Thailand: An Analytical History. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. hdl:2027/heb.02474. ISBN 9781597400923.

- ^ Bōtan (1 January 2002). Letters from Thailand: A Novel. ISBN 9747551675.

- ^ The Symbolism of Sondhi's Hat[not specific enough to verify]

- ^ "Thai PM condemns race-baiting at anti-govt rally". Asia One. Agence France-Presse. 5 August 2008. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ "Sondhi Limthongkul". Political Prisoners in Thailand. 23 January 2009.

- ^ Banyan (21 January 2014). "Why Thai politics is broken". The Economist. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Lintner, Bertil (2003). Blood Brothers: The Criminal Underworld of Asia. Macmillan Publishers. p. 234. ISBN 1-4039-6154-9.

- ^ Stuart-Fox, Martin (2003). A Short History of China and Southeast Asia: Tribute, Trade and Influence. Allen & Unwin. p. 126. ISBN 1-86448-954-5.

- ^ Smith NieminenWin (2005). Historical Dictionary of Thailand (2nd ed.). Praeger Publishers. p. 231. ISBN 0-8108-5396-5.

- ^ Rosalind C. Morris (2000). In the Place of Origins: Modernity and Its Mediums in Northern Thailand. Duke University Press. p. 334. ISBN 0-8223-2517-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Sowell, Thomas (1997). Migrations and Cultures: A World View. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-04589-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wongsurawat, Wasana (November 2008). "Contending for a Claim on Civilization: The Sino-Siamese Struggle to Control Overseas Chinese Education in Siam". Journal of Chinese Overseas. 4 (2). pp. 161–182.

- ^ Leifer, Michael (1996). Dictionary of the Modern Politics of South-East Asia. Routledge. p. 204. ISBN 0-415-13821-3.

- ^ "Bilateral Relations". Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the People's Republic of China. 23 October 2003. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

On July 1, 1975, China and Thailand established Diplomatic relations.

- ^ Dixon, Chris (1999). The Thai Economy: Uneven Development and internationalisation. Routledge. p. 267. ISBN 0-415-02442-0.

- ^ Paul J. Christopher (2006). 50 Plus One Greatest Cities in the World You Should Visit. Encouragement Press, LLC. p. 25. ISBN 1-933766-01-8.

- ^ Bōtan (1 January 2002). Letters from Thailand. ISBN 9747551675.

- ^ Knodel, John; Hermalin, Albert I. (2002). "The Demographic, Socioeconomic, and Cultural Context of the Four Study Countries". The Well-Being of the Elderly in Asia: A Four-Country Comparative Study. University of Michigan Press: 38–39.

- ^ Gorter, Durk (2006). Linguistic Landscape: A New Approach to Multilingualism. Multilingual Matters. p. 43. ISBN 1-85359-916-6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Unger, Danny (1998). Building Social Capital in Thailand: Fibers, Finance and Infrastructure. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521639316.

- ^ Crawfurd, John (21 August 2006) [1830]. "Chapter I". Journal of an Embassy from the Governor-general of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China. Volume 1 (2nd ed.). London: H. Colburn and R. Bentley. p. 30. OCLC 03452414. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Jump up to: a b Szumer, Zacharias (29 April 2020). "Coronavirus spreads anti-Chinese feeling in Southeast Asia, but the prejudice goes back centuries". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Baker, Chris (24 January 2020). "The formidable alliance underlying modern Thai history" (Book review). Bangkok Post. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ Wiese, York A. (April 2013). "The "Chinese Education Problem" of 1948" (PDF). Occasional Paper Series No. 15. Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Freiburg (Germany): 6. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cornwell, Grant Hermans; Stoddard, Eve Walsh (2000). Global Multiculturalism: Comparative Perspectives on Ethnicity, Race, and Nation. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 67. ISBN 978-0742508828.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Chirot, Daniel; Reid, Anthony (1997). Essential Outsiders: Chinese and Jews in the Modern Transformation of Southeast Asia and Central Europe. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0295976136.

- ^ Viraphol, Sarasin (1972). The Nanyang Chinese. Institute of Asian Studies, Chulalongkorn University Press. p. 10.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Richter, Frank-Jürgen (1999). Business Networks in Asia: Promises, Doubts, and Perspectives. Praeger. ISBN 978-1567203028.

- ^ Joint Economic Committee Congress of the United States (1997). China's Economic Future: Challenges to U.S. Policy. Studies on Contemporary China. Routledge. p. 425. ISBN 978-0765601278.

- ^ Welch, Ivan. Southeast Asia—Indo or China (PDF). Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Foreign Military Studies Office. p. 37. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2012.

- ^ Current Issues On Industry Trade And Investment. United Nations Publications. 2004. p. 4. ISBN 978-9211203592.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tipton, Frank B. (2008). Asian Firms: History, Institutions and Management. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 277. ISBN 978-1847205148.

- ^ Buzan, Barry; Foot, Rosemary (2004). Does China Matter?: A Reassessment: Essays in Memory of Gerald Segal. Routledge. p. 82. ISBN 978-0415304122.

- ^ Wong, John (2014). The Political Economy Of Deng's Nanxun: Breakthrough In China's Reform And Development. World Scientific Publishing Company. p. 214. ISBN 9789814578387.

- ^ "Malaysian Chinese Business: Who Survived the Crisis?". Kyoto Review. Archived from the original on 9 February 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ Nam, Suzanne (1 September 2010). "Thailand's 40 Richest". Forbes. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ Yeung, Henry. "Economic Globalization, Crisis and the Emergence of Chinese Business Communities in Southeast Asia" (PDF). National University of Singapore.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sowell, Thomas (2006). Black Rednecks & White Liberals: Hope, Mercy, Justice and Autonomy in the American Health Care System. Encounter Books. p. 84. ISBN 978-1594031434.

- ^ "Chaleo Yoovidhya". Forbes. March 2012. Archived from the original on 17 March 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

Net Worth $5 B As of March 2012 #205 Forbes Billionaires, #3 in Thailand

- ^ "Sidewinder: Chinese Intelligence Services and Triads Financial Links in Canada". Primetimecrime.com. 24 June 1997. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Yu, Bin (1996). Dynamics and Dilemma: Mainland, Taiwan and Hong Kong in a Changing World. Edited by Yu Bin and Chung Tsungting. Nova Science. ISBN 978-1560723035.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ju, Yanan; Chu, Yen-An (1996). Understanding China: Center Stage of the Fourth Power. State University of New York Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0791431221.

- ^ Richter, Frank-Jurgen (2002). Redesigning Asian Business: In the Aftermath of Crisis. Quorum Books. p. 85. ISBN 978-1567205251.

- ^ Myers, Peter (2 July 2005). "The Jewish Century" (Book review). Retrieved 7 May 2012. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Slezkine, Yuri (27 June 2011). The Jewish Century. ISBN 978-1400828555. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Yeung, Henry; Tse Min Soh (25 August 2000). "Corporate Governance and the Global Reach of Chinese Family Firms in Singapore" (PDF). Corporate Governance and the Global Reach of Chinese Family Firms in Singapore. Department of Geography, National University of Singapore. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Redding, Gordon (1990). The Spirit of Chinese Capitalism. De Gruyter. p. 32. ISBN 978-3110137941.

- ^ Weidenbaum, Murray. "The Bamboo Network: Asia's Family-run Conglomerates". Strategy-business.com. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ Murray L Weidenbaum (1 January 1996). The Bamboo Network: How Expatriate Chinese Entrepreneurs are Creating a New Economic Superpower in Asia. Martin Kessler Books, Free Press. pp. 4–8. ISBN 978-0-684-82289-1.

- ^ Yeung, Henry. "Change and Continuity in SE Asian Ethnic Chinese Business" (PDF). Department of Geography, National University of Singapore.

- ^ Goossen, Richard. "The spirit of the overseas Chinese entrepreneur, by" (PDF).

- ^ Chen, Min (1995). Asian Management Systems: Chinese, Japanese and Korean Styles of Business. Cengage Learning. p. 65. ISBN 978-1861529411.

- ^ Snitwongse, Kusuma; Thompson, Willard Scott (2005). Ethnic Conflicts in Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (published 30 October 2005). p. 154. ISBN 978-9812303370.

- ^ White, Lynn (2009). Political Booms: Local Money And Power In Taiwan, East China, Thailand, And The Philippines. Contemporary China. WSPC. p. 26. ISBN 978-9812836823.

- ^ Wongsurawat, Wasana (2 May 2016). "Beyond Jews of the Orient: A New Interpretation of the Problematic Relationship between the Thai State and Its Ethnic Chinese Community". Cultural Studies. Positions: Asia Critique. 2. Duke University Press. 24 (2): 555–582. doi:10.1215/10679847-3458721. S2CID 148553252.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gomez, Edmund (2012). Chinese business in Malaysia. Routledge. p. 94. ISBN 978-0415517379.

- ^ Martin E. Marty, R. Scott Appleby, John H. Garvey, Timur Kuran (July 1996). Fundamentalisms and the State: Remaking Polities, Economies, and Militance. University Of Chicago Press. p. 390. ISBN 0-226-50884-6.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Tong Chee Kiong; Chan Kwok Bun (2001). Rethinking Assimilation and Ethnicity: The Chinese of Thailand. Alternate Identities: The Chinese of Contemporary Thailand. pp. 30–34.

- ^ Jean Elizabeth DeBernardi (2006). The Way That Lives in the Heart: Chinese Popular Religion and Spirits Mediums in Penang, Malaysia. Stanford University Press. pp. 25–30. ISBN 0-8047-5292-3.

- ^ "»ÃÐÇѵԡÒÃ;¾¢Í§¨Õ¹ÁØÊÅÔÁ". Oknation.net. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ William Allen Smalley (1994). Linguistic Diversity and National Unity: Language. University of Chicago Press. pp. 212–3. ISBN 0-226-76288-2.

- ^ Andrew D.W. Forbes (1988). The Muslims of Thailand. Soma Prakasan. ISBN 974-9553-75-6.

- ^ Mirin MacCarthy. "Successfully Yours: Thanet Supornsaharungsi." Pattaya Mail. [Undated] 1998.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 26 April 2005. Retrieved 26 April 2005.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Preston et al. (1997), p. 464; 51. Phya Manopakarana Nitidhada spoke perfect English and was always very friendly to England. He is three parts Chinese. His wife, a favorite lady-in-waiting to the ex-Queen, was killed in a motor accident in 1929 when on an official visit to Indo-China.

- ^ D. Insor (1957). Thailand: A Political, Social, and Economic Analysis. Praeger. p. 138.

- ^ ทายาทพระยาพหลฯ เล่าถึงคณะราษฎรในความทรงจำ ทั้งชีวิตยอมปฏิวัติ 24 มิ.ย.ได้ครั้งเดียว. Prachatai (in Thai). 30 June 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- ^ Batson, Benjamin Arthur; Shimizu, Hajime (1990). The Tragedy of Wanit: A Japanese Account of Wartime Thai Politics. University of Singapore Press. p. 64. ISBN 9971622467. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b An Impressive Day at M.R. Kukrit's Home Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine; Thailand Bibliography

- ^ Gerald W. Fry (18 June 2012). "Research & Articles on Pridi Banomyong". BookRags. Archived from the original on 30 October 2011.

Pridi was included in UNESCO's list of Great Personalities and Historic Events for the year 2000, and this year was declared by UNESCO as the centennial of Pridi. Also, the Université Paris (1 PanthéonSorbonne) in 2000 celebrated the centenary of Pridi and honored him as "one of the great constitutionalists of the twentieth century," comparing him to such figures as Rousseau, Montesquieu, and de Tocqueville.

- ^ [泰国] 洪林, 黎道纲主编 (April 2006). 泰国华侨华人研究 (in Chinese). 香港社会科学出版社有限公司. p. 17. ISBN 962-620-127-4.

- ^ [泰国] 洪林, 黎道纲主编 (April 2006). 泰国华侨华人研究 (in Chinese). 香港社会科学出版社有限公司. pp. 17, 185. ISBN 962-620-127-4.

- ^ 臺北科技大學紅樓資訊站 (in Chinese). National Taipei University of Technology. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- ^ [泰国]洪林,黎道纲主编 (April 2006). 泰国华侨华人研究 (in Chinese). 香港社会科学出版社有限公司. p. 17. ISBN 962-620-127-4.

- ^ Chaloemtiarana, Thak (2007), Thailand: The Politics of Despotic Paternalism, Ithaca NY: Cornell Southeast Asia Program, p. 88, ISBN 978-0-8772-7742-2

- ^ Gale, T. 2005. Encyclopedia of World Biographies.

- ^ Smith Nieminen Win (2005). Historical Dictionary of Thailand (2nd ed.). Praeger Publishers. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-8108-5396-6.

- ^ Richard Jensen, Jon Davidann, Sugita (2003). Trans-Pacific Relations: America, Europe, and Asia in the Twentieth Century. Praeger Publishers. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-275-97714-6.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Peagam, Nelson (1976), "Judge picks up the reigns", Far Eastern Economic Review, p. 407

- ^ Krīangsak, Chamanan. thīralưk Ngān Phrarātchathān Phlœng Sop Phon ʻēk Krīangsak Chamanan: ʻadīt Nāyokratthamontrī 12 Pho. Yo. 2549 translated as Official Documents of Cremation Volumes in honour of former Thai president Kriangsak Chomanan. Krung Thēp: Khunying Wirat Chamanan, 2006. Print.

- ^ 曾经叱咤风云的泰国政坛澄海人. ydtz.com (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- ^ 潮汕人 (in Chinese).[permanent dead link]

- ^ Chris Baker, Pasuk Phongpaichit (20 April 2005). A History of Thailand. Cambridge University Press. pp. 154 and 280. ISBN 0-521-81615-7.

- ^ [泰国] 洪林, 黎道纲主编 (April 2006). 泰国华侨华人研究. 香港社会科学出版社有限公司. p. 185. ISBN 962-620-127-4.

- ^ 泰国华裔总理不忘"本". csonline.com.cn (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 22 April 2009.

- ^ [泰国] 洪林, 黎道纲主编 (April 2006). 泰国华侨华人研究 (in Chinese). 香港社会科学出版社有限公司. p. 185. ISBN 962-620-127-4.

- ^ The days before ceasefire between SLORC AND NMSP on 25 June 1995 Archived 17 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 泰国华裔地位高 出过好几任总理真正的一等公民. Sohu (in Chinese).

- ^ "Former PM Banharn dies at 83". Bangkok Post. 23 April 2016.

- ^ Duncan McCargo, Ukrist Pathmanand (2004). The Thaksinization Of Thailand. Nordic Institute of Asian Studies. p. Introduction: Who is Thaksin Shinawatra?, 4. ISBN 978-87-91114-46-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tumcharoen, Surasak (29 November 2009). "A very distinguished province: Chanthaburi has had some illustrious citizens". Bangkok Post.

- ^ [泰国] 洪林, 黎道纲主编 (April 2006). 泰国华侨华人研究 (in Chinese). 香港社会科学出版社有限公司. p. 187. ISBN 962-620-127-4.

- ^ "Profile: Abhisit Vejjajiva". BBC News. 17 March 2010. Archived from the original on 8 February 2011. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 7 April 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Peas in a pod they are not

- ^ http://www.ratchakitcha.soc.go.th/DATA/PDF/2559/D/087/19.PDF

- ^ ประวัติการเรียน พล.อ.ประยุทธ์ จันทร์โอชา นายกรัฐมนตรีคนที่ 29 (in Thai). เอ็มไทย. 22 February 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

Further reading[]

- Chansiri, Disaphol (2008). "The Chinese Émigrés of Thailand in the Twentieth Century". Cambria Press. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Chantavanich, Supang (1997). Leo Suryadinata (ed.). From Siamese-Chinese to Chinese-Thai: Political Conditions and Identity Shifts among the Chinese in Thailand. Ethnic Chinese as Southeast Asians. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 232–259.

- Tong Chee Kiong; Chan Kwok Bun (eds.) (2001). Alternate Identities: The Chinese of Contemporary Thailand. Times Academic Press. ISBN 981-210-142-X.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Skinner, G. William. Leadership and Power in the Chinese Community in Thailand. Ithaca (Cornell University Press), 1958.

- Sng, Jeffery; Bisalputra, Pimpraphai (2015). A History of the Thai-Chinese. Editions Didier Millet. ISBN 978-981-4385-77-0.

- Wongsurawat, Wasana (October 2019). The Crown and the Capitalists; The Ethnic Chinese and the Founding of the Thai Nation. Critical Dialogues in Southeast Asian Studies (Paper ed.). Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295746241. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

External links[]

- Dr. Wasana Wongsurawat lectures about her book The Crown and the Capitalists; The Ethnic Chinese and the Founding of the Thai Nation, 15 January 2020 (video)

- Thai-Chinese chamber of commerce

- Thai Chinese.net

- (in Thai) Thai Chinese.net

Associations[]

- The Chinese Association in Thailand (Chong Hua)

- Teochew Association of Thailand

- Hakka Association of Thailand

- (in Thai) Thai Hainan Trade association of Thailand

- Fujian Association of Thailand

Miscellaneous[]

- Chinese diaspora in Thailand

- Chinese diaspora by country

- China–Thailand relations

- Ethnic groups in Thailand