The Collector (1965 film)

| The Collector | |

|---|---|

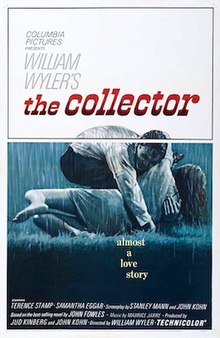

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | William Wyler |

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on | The Collector by John Fowles |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Maurice Jarre |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date | |

Running time | 119 minutes |

| Countries | United Kingdom United States[2] |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $3.5 million (rentals)[3] |

The Collector is a 1965 British-American psychological horror film[4][5] directed by William Wyler and starring Terence Stamp and Samantha Eggar. Its plot follows a young Englishman who stalks a beautiful art student before abducting and holding her captive in the basement of his rural farmhouse. It is based on the 1963 novel of the same title by John Fowles, with the screenplay adapted by Stanley Mann and John Kohn. Wyler turned down The Sound of Music to direct the film.

Most of the film was shot on soundstages in Los Angeles, though exterior sequences were filmed on location in London, Forest Row in East Sussex and Westerham in Kent. Filming occurred in the late spring and early summer of 1964. Wyler's original cut ran approximately three hours but was trimmed to two hours at the insistence of the studio and producer.

The Collector premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in May 1965, where both Stamp and Eggar won the awards for Best Actor and Best Actress, respectively. Upon its theatrical release in June 1965, the film received largely favourable reviews. Eggar won a Golden Globe Award for Best Actress in a Motion Picture – Drama for her performance, and was also nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actress, while Wyler received a nomination for Best Director. It was the last of Wyler's record 12 Academy Award nominations for Best Director.

Plot[]

Freddie is a lonely, socially-awkward young man who purchases a farmhouse with winnings he has earned from the football pools. An amateur entomologist, he spends his time capturing butterflies, of which he has a large collection. Frederick begins stalking a bourgeois London art student named Miranda Grey. One day, Frederick follows Miranda into a pub in Hampstead before abducting her on the street, incapacitating her with chloroform.

Miranda awakens inside the cavernous, windowless stone cellar of Freddie's 17th century farmhouse, which he has adorned with a bed, furnishings, clothing, painting tools, and an electric heater. Miranda assumes she has either been taken for ransom or to be used as a sex slave, and insists to Freddie that her father is not wealthy. Freddie explains he is not seeking sex or ransom; he explains that he and Miranda used to ride on the same bus years earlier in Reading and that he continued to follow her into London after she enrolled in art school. When Freddie proclaims his love for Miranda, she fakes appendicitis as a ploy to escape but is caught. Freddie agrees that he will free Miranda after four weeks, an allotted period he believes will allow her to "get to know him".

Freddie gradually allows Miranda small luxuries, such as leaving the cellar to obtain sunlight and take baths in the house under his supervision. When Freddie fondles her aggressively, Miranda tells him she will not fight him should he rape her, but that she will lose all respect for him. During one of her baths, Freddie's neighbour, Colonel Whitcombe, arrives at the house to introduce himself, resulting in Frederick gagging Miranda and tying her to pipes in the bathroom. She floods the bathroom in an attempt to get Whitcombe's attention, but Frederick diverts him, claiming his girlfriend inadvertently left the tub running.

Freddie recurrently mentions one of Miranda's boyfriends, with whom he observed her socialising on numerous occasions. He allows Miranda to write a letter to her mother, but discovers a small piece of paper in the envelope asking for help, and tears the letter apart in front of her. During a conversation about art and literature, Miranda further alienates Freddie, who accuses her of being an elitist. He proclaims that they could never be friends in "the real world". On the 30th—and allegedly final day of her captivity, Freddie prepares a meal in the house for Miranda, and gives her a dress to wear for the occasion. Over dinner, he asks Miranda to marry him. She agrees, but Frederick senses her hesitation. She attempts to flee the house, but Freddie corners her in his study and chloroforms her before lying with her in an upstairs bedroom. When she regains consciousness in the cellar, Frederick assures Miranda he did not rape her. He tells her he intends to keep her until she "tries" to fall in love with him. After having a bath one night, Miranda unsuccessfully attempts to seduce him, but he senses her artifice and compares her to a prostitute.

When he escorts her back to the cellar during a rainstorm, Miranda seizes a shovel, with which she strikes Freddie on the head. Though wounded, Freddie takes advantage of Miranda's subsequent hesitation and manages to drag her back into the cellar and she accidentally breaks the electric heater just after their struggle. Miranda remains locked in the cold cellar, soaking wet, while Frederick receives medical attention. He returns three days later to find Miranda ill with pneumonia and goes into town to get a doctor. When Freddie returns, having changed his mind about a doctor, he finds Miranda dead. Freddie buries Miranda's corpse under an oak tree on his property. A short time later, Freddie, convinced Miranda brought her fate on herself, again drives around, now stalking a young nurse in the hopes that he might have better success overall with a different sort of woman.

Production[]

Screenplay[]

The screenplay was written by Stanley Mann and John Kohn, based on the novel by John Fowles. However, Terry Southern contributed an uncredited script revision for Wyler after the producers became unhappy with the book's original darker ending; they wanted Miranda to escape. Southern's "happier" ending was rejected by Wyler.

Casting[]

| Actor | Character | |

|---|---|---|

| Terence Stamp | Frederick "Freddie" Clegg | |

| Samantha Eggar | Miranda Grey | |

| Mona Washbourne | Aunt Annie | |

| Maurice Dallimore | Colonel Whitman | |

| Allyson Ames | First victim | |

| Edina Ronay | Nurse / next victim |

Wyler considered a number of performers for the two central roles of Freddie Clegg and Miranda Grey, around whom the film almost exclusively revolves.[6] Sarah Miles and Natalie Wood were considered for the role of Miranda, while Anthony Perkins and Dean Stockwell were considered for the role of Freddie.[7] Wyler ultimately chose English actors Terence Stamp and Samantha Eggar because he felt that together they possessed the correct chemistry of sexual tension and awkwardness.[8] Wyler was also aware that Stamp had been attracted to Eggar while the two were studying together at Webber Douglas Academy of Dramatic Art.[9]

The supporting role of Aunt Annie was played by Mona Washbourne, while Kenneth More was cast as George Paston, or "G.P.", a man in the source novel to whom Miranda writes to extensively, and whom she admires. More's scenes were ultimately excised from the final cut of the film.[10]

Filming[]

"At first I felt that I just couldn't do it. It took me five weeks to be on Wyler's wave length."

—Eggar on the difficulties acclimating to Wyler's work style, 1965[11]

Principal photography for The Collector began in May 1964 at the Columbia Pictures soundstages in Los Angeles, California.[12] Tensions between Eggar, and Wyler and Stamp arose after Wyler privately instructed Stamp to stay in character and give Eggar the cold shoulder during the filming.[13] Wyler was also unfriendly toward Eggar on set, as he felt the atmosphere would impose a sense of isolation for her, thus eliciting a stronger performance.[14] Fowles observed that "the favorite sport on the Columbia lot is making fun of her behind her back."[15] The stress on set resulted in Eggar losing 10 pounds (4.5 kg) during rehearsals and flubbing her lines.[15] "I guess I was supposed to feel trapped, and I did," she recalled.[15] Three weeks into rehearsals, Wyler fired Eggar as he was displeased with her performance, resulting in the production shutting down.[8] After the film's second-unit director completed a full read-through of the entire screenplay with Eggar, she was re-hired under the provision that Kathleen Freeman, a character actress, serve as her coach on set.[6][15] Off-camera, Eggar was allowed to speak only to Freeman.[15] Eggar stated that Wyler was "100% demanding. He works you to your peak. When it's over, you realize that you have done the best you could possibly do."[11]

A journalist visiting the set during one day of filming noted: "The dialogue was tricky. The movement of the camera was difficult. It was the kind of scene that rubs nerves raw and kindles outbursts of temperament. But not when Wyler's behind the camera. The doughty little director spent the entire morning rehearsing and then shooting the scene time and time again. Stamp and Eggar were as meek and cooperative as neophytes."[16]

In late June 1964, the production relocated to England for filming of the exterior scenes, which included on-location shooting in Mount Vernon, Hampstead, London and Forest Row, East Sussex.[14] The exteriors of Freddie's house were filmed at a 400-year-old farmhouse in rural Kent.[14] After location shoots were completed in England, the production returned to Los Angeles, where the remainder of the shoot occurred, concluding in mid-July.[14] By the end of the shoot, Eggar had reportedly lost a total of 14 pounds (6.4 kg).[11]

Post-production[]

The original cut of The Collector ran for three hours.[17] Because of pressure from his producers, Wyler was forced to cut the film heavily, removing 35 minutes of prologue material starring Kenneth More. Wyler said, "Some of the finest footage I ever shot wound up on the cutting room floor, including Kenneth's part."[18]

Release[]

The Collector premiered at the Cannes Film Festival on May 20, 1965, where both Stamp and Eggar won awards for Best Actor and Best Actress, respectively.[19] This marked the first time in the festival's history that two performers from the same film won both awards.[19] The film had its North American premiere in New York City on June 17, 1965.[1] It premiered in London on October 13, 1965.

Critical response[]

Bosley Crowther of The New York Times wrote that Terence Stamp's character was "entirely mystifying and fascinating" at the beginning, but once it became apparent that nothing more was going to be learned about him "he tends to become monotonous, and finally, a melodramatic blob." Crowther's review concluded that Wyler had made "a tempting and frequently startling, bewitching film, but he has failed to make it any more than a low-key chiller that melts in a conventional puddle of warm blood towards the end."[20] A positive review in Variety called the film "a solid, suspenseful enactment of John Fowles' bestselling novel," directed by Wyler "with taste and imagination."[21] Philip K. Scheuer of the Los Angeles Times wrote of the film that "if it is too clinical to touch any of the livelier emotions — the strongest one it can arouse is hope, and this is blasted again and again — it still manages to picque intellectual curiosity sufficiently to attract the art-house patron in search of the odd or offbeat."[22]

Philip Kopper of The Washington Post called it "a fantastic film" that he thought was stronger than the novel because Wyler "removed many of the redundancies and collatoral elements."[23] Writing for The Courier-Journal, William Mootz praised the film for its "atmosphere of oppressive tension" and an "anguishing excursion into horror fiction."[24]

Edith Oliver of The New Yorker panned the film as "a preposterous fake that pretends to deal seriously with psychopathic behavior but cannot be taken seriously even as a thriller. It evokes no pity, no wonder, no horror, no suspense, no belief, and who cares how it comes out?"[25] John Russell Taylor of Sight & Sound wrote that while the film played as a "diluted version" of the novel, "what we are left with, though paper-thin, is perfectly clear and rather grippingly told."[26] The Monthly Film Bulletin stated that "all the tensions between scenes, the undercurrents beneath what the characters say and do, seem to have disappeared, leaving a good story adequately told but without much cutting edge ... On the other hand, the main body of the story comes over remarkably well."[27]

As of 2019, on the internet review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, The Collector has a 100% approval rating, based on 13 reviews.[28]

Accolades[]

| Awards | Category | Recipient(s) | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Actress in a Leading Role | Samantha Eggar | Nominated | [29] |

| Best Director | William Wyler | Nominated | [30] | |

| Best Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium | John Kohn | Nominated | [29] | |

| Cannes Film Festival | Best Actor | Terence Stamp | Won | [31] |

| Best Actress | Samantha Eggar | Won | ||

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Performance by an Actress in a Motion Picture - Drama | Samantha Eggar | Won | [32] |

| Best Motion Picture - Drama | William Wyler | Nominated | ||

| Best Screenplay | John Kohn | Nominated | ||

| Best Director | William Wyler | Nominated | ||

| Sant Jordi Awards | Best Actress in a Foreign Film | Samantha Eggar | Won | [33] |

| Best Foreign Film | William Wyler | Won |

Home media[]

In the United States, Columbia Pictures Home Entertainment first released The Collector on VHS in 1980.[34] Sony Pictures Home Entertainment issued a DVD on October 9, 2002.[35] A Blu-ray was subsequently released by Image Entertainment in 2011.[36] On September 24, 2018, the United Kingdom-based Powerhouse Films released a region-free Blu-ray in their limited edition Indicator series; this edition features numerous interviews and archival material as bonus features.[37] This marked the film's first availability on Blu-ray in the United Kingdom.[37]

Inspiration for crimes[]

In 1988, Robert Berdella held his male victims captive and photographed their torture before killing them. Upon being apprehended, he claimed that the film version of The Collector had been an integral inspiration to him after seeing it as a teenager.[38][39]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Collector (1965)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ Meehan 2014, p. 10.

- ^ This figure consists of anticipated rentals accruing distributors in North America. See "Top Grossers of 1965", Variety, 5 January 1966 p 36

- ^ Luhr 1987, p. 611.

- ^ Meehan 2014, p. 6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Monush 2009, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Haun 2000, p. 28.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Monush 2009, p. 23.

- ^ Warburton 2015, p. 25.

- ^ Warburton 2015, p. 30.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Carroll, Kathleen (June 20, 1965). "Redhead, Mad for Pink, Is Going to Have a Baby". New York Daily News. New York City. p. 10 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Monush 2009, pp. 22, 24.

- ^ "The Collector". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved June 21, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Monush 2009, p. 24.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Warburton 2015, p. 26.

- ^ Scott, Vernon (May 31, 1964). "Wyler Only 'Prima Donna' At Columbia". The San Bernardino County Sun. San Bernardino, California. p. 51 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Vipond 2000, p. 24.

- ^ McClelland 1972, p. 125.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Premiere Scheduled for 'The Collector'". The Morning Call. Paterson, New Jersey. June 2, 1965. p. 30 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (June 18, 1965). "Terence Stamp Stars in 'The Collector'". The New York Times: 28.

- ^ "Film Reviews: The Collector". Variety: 6. May 26, 1965.

- ^ Scheuer, Philip K. (June 20, 1965). "'The Collector' Gathers Dread and Curiosity". Los Angeles Times. Calendar, p. 4.

- ^ Kopper, Philip (July 2, 1965). "'Collector' Lives Out Fantasies". The Washington Post: D10.

- ^ Mootz, William (September 23, 1965). "Nightmarish 'Collector' Makes Viewers Sweat". The Courier-Journal. Louisville, Kentucky. p. B6 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Oliver, Edith (June 26, 1965). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker: 80.

- ^ Taylor, John Russell (Autumn 1965). "The Collector". Sight & Sound. 34 (4): 201.

- ^ "The Collector". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 32 (382): 162. November 1965.

- ^ "The Collector (1965)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Monush 2009, p. 22.

- ^ Booker 2011, p. 422.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: The Collector". Festival de Cannes. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013.

- ^ "The Collector". Golden Globe Awards. Archived from the original on July 17, 2019.

- ^ Warburton 2015, p. 28.

- ^ The Collector. Columbia Pictures Home Entertainment (VHS). VH10148.

- ^ Cressey, Earl (October 9, 2002). "The Collector: DVD Review". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on July 17, 2019.

- ^ "The Collector Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on July 17, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Collector". Powerhouse Films. Archived from the original on July 17, 2019.

- ^ Newton 2002, p. 23.

- ^ Bob Berdella – The Crime library Archived 2007-09-21 at the Wayback Machine

Sources[]

- Booker, Keith M. (2011). Historical Dictionary of American Cinema. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-810-87459-6.

- Haun, Harry (2000). The Cinematic Century: An Intimate Diary of America's Affair with the Movies. New York: Applause. ISBN 978-1-557-83400-3.

- Luhr, William (1987). World Cinema Since 1945. New York: Ungar. ISBN 978-0-804-43078-4.

- McClelland, Doug (1972). The Unkindest Cuts: The Scissors and the Cinema. London: A. S. Barnes. ISBN 978-0-498-07825-5.

- Meehan, Paul (2014). Horror Noir: Where Cinema's Dark Sisters Meet. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-786-46219-3.

- Monush, Barry (2009). Everybody's Talkin': The Top Films of 1965-1969. New York: Applause Books. ISBN 978-1-557-83618-2.

- Newton, Michael (2002). The Encyclopedia of Kidnappings. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-1-438-12988-4.

- Vipond, Diann, ed. (2000). Conversations with John Fowles. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-578-06191-4.

- Warburton, Eileen (2015). "Bluebeard's Basement: The Collector On Film". In Aubrey, James (ed.). Filming John Fowles: Critical Essays on Motion Picture and Television Adaptations. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. pp. 13–34. ISBN 978-0-786-49764-5.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Collector (1965 film) |

- 1965 films

- English-language films

- 1965 crime drama films

- 1960s crime thriller films

- 1960s psychological drama films

- 1960s psychological thriller films

- 1960s thriller drama films

- American crime drama films

- American crime thriller films

- American psychological horror films

- American films

- American thriller drama films

- Columbia Pictures films

- Films about kidnapping

- Films about psychopaths

- Films about stalking

- Films based on British novels

- Films based on works by John Fowles

- Films directed by William Wyler

- Films featuring a Best Drama Actress Golden Globe-winning performance

- Films scored by Maurice Jarre

- Films set in England

- Films set in Sussex

- Films shot in London

- Films shot in East Sussex

- Films shot in Kent

- Films shot in Los Angeles

- Films with screenplays by Stanley Mann