The Holocaust in Russia

The Holocaust in Russia is the Nazi crimes during the occupation of Russia (Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic) by Nazi Germany.

On the eve of the Holocaust[]

The Soviet Union did grant official "equality of all citizens regardless of status, sex, race, religion, and nationality." The years before the Holocaust were an era of rapid change for Soviet Jews, leaving behind the dreadful poverty of the Pale of Settlement. 40% of the population in the former Pale left for large cities within the Soviet Union. Emphasis on education and movement from countryside shtetls to newly industrialized cities allowed many Soviet Jews to enjoy overall advances under Joseph Stalin and to become one of the most educated population groups in the world. Due to Stalinist emphasis on its urban population, interwar migration inadvertently rescued countless Soviet Jews—Nazi Germany penetrated the entire former Jewish Pale, but were kilometers short of Leningrad and Moscow.

World War II[]

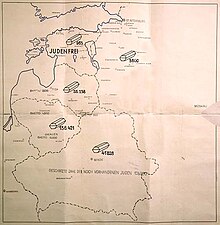

On 22 June 1941, Adolf Hitler abruptly broke the non−aggression pact and invaded the Soviet Union. The Soviet territories occupied by early 1942, including all of Belarus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Ukraine and most Russian territory west of the line Leningrad–Moscow–Rostov, contained about four million Jews, including hundreds of thousands who had fled Poland in 1939. Despite the chaos of the Soviet retreat, some effort was made to evacuate Jews, who were either employed in the military industries or were family members of servicemen. Of 4 million about a million succeeded in escaping further east. The "Holocaust by bullet" was the task of SS death squads called Einsatzgruppen, under the overall command of Reinhard Heydrich. These had been used on a limited scale in Poland in 1939, but were now organized on a much larger scale. Most of their victims were defenseless Jewish civilians (not a single Einsatzgruppe member was killed in action during these operations).[1] They used their skills to become efficient killers, according to Michael Berenbaum.[2] By the end of 1941, however, the Einsatzgruppen had killed only 15 percent of the Jews in the occupied Soviet territories, and it was apparent that these methods could not be used to kill all the Jews of Europe. Even before the invasion of the Soviet Union, experiments with killing Jews in the back of vans using gas from the van's exhaust had been carried out, and when this proved too slow, more lethal gasses were tried. Units of the Wehrmacht also participated in many aspects of the Holocaust in Russia.

The Nazi Genocide of the Jews carried by German Einsatzgruppen, and Wehrmacht along with local collaborators resulted in almost complete annihilation of the Jewish population over the entire territory temporary occupied by Germany and its allies.[3] During World War II, Léon Poliakov established the Center of Contemporary Jewish Documentation (1943) and after the war, he assisted Edgar Faure at the Nuremberg Trial.

Massacres[]

- Gully of Petrushino, near Taganrog, October 1941

After World War II[]

Following the war, the Soviet Union suppressed or downplayed the impact of Nazi crimes on its Jewish citizens. An anti-semitic campaign against "rootless cosmopolitans" (i.e. "Zionists") followed. On 12 August 1952, in the event known as the Night of the Murdered Poets, thirteen most prominent Yiddish writers, poets, actors and other intellectuals were executed on the orders of Joseph Stalin, among them Peretz Markish, Leib Kvitko, David Hofstein, Itzik Feffer and David Bergelson.[4]

See also[]

- Krasnodar Trial — the 1943 war crimes trial in the Russian SSR

- Generalplan Ost

- Russian Research and Educational Holocaust Center

- War crimes of the Wehrmacht

References[]

- ^ Hilberg, Raul cited in Berenbaum, Michael. The World Must Know. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2nd edition, 2006, p. 93.

- ^ Berenbaum, Michael. The World Must Know. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2nd edition, 2006, p. 93.

- ^ "Request Rejected". Yad Vashem. Retrieved 2014-03-13.

- ^ Stalin's Secret Pogrom: The Postwar Inquisition of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee Archived 2005-10-28 at the Wayback Machine (introduction) by

Further reading[]

- Acemoglu, D.; Hassan, T. A.; Robinson, J. A. (2011). "Social Structure and Development: A Legacy of the Holocaust in Russia". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 126 (2): 895–946. doi:10.1093/qje/qjr018.

- Holocaust stubs

- The Holocaust in Russia

- The Holocaust by country

- World War II prisoners of war massacres

- Eastern Front (World War II)

- Soviet Union in World War II