Tibet under Qing rule

| Tibet under Qing rule | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1720–1912 | |||||||||

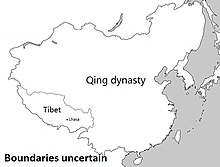

Tibet and the Qing dynasty in 1820. | |||||||||

| Capital | Lhasa | ||||||||

| • Type | Theocracy headed by Dalai Lama under Qing protectorate[1][2] | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 1720 | |||||||||

• Tibet national border established at Dri River | 1725–1726 | ||||||||

| 1750 | |||||||||

• Sino-Nepalese War | 1788–1792 | ||||||||

• British invasion of Tibet | 1903–1904 | ||||||||

| 1910-1911 | |||||||||

| 1912 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| History of Tibet |

|---|

|

|

| See also |

|

|

|

Tibet under Qing rule[3][4] refers to the Qing dynasty's relationship with Tibet from 1720 to 1912.[5][6][7] During this period, Qing China regarded Tibet as a vassal state.[8] Tibet considered itself an independent nation with only a "priest and patron" relationship with the Qing Dynasty.[9][10][11][12] Scholars such as Melvyn Goldstein have considered Tibet to be a Qing protectorate.[13][1]

By 1642, the Güshri Khan of Khoshut Khanate had reunified Tibet under the spiritual and temporal authority of the 5th Dalai Lama of the Gelug school. In 1653, the Dalai Lama travelled on a state visit to the Qing court, and was received in Beijing and "recognized as the spiritual authority of the Qing Empire".[14] The Dzungar Khanate invaded Tibet in 1717, and were subsequently expelled by Qing in 1720. The Qing emperors then appointed imperial residents known as ambans to Tibet, most of them ethnic Manchus that reported to the Lifan Yuan, a Qing government body that oversaw the empire's frontier.[15][16] During the Qing era, Lhasa retained its political autonomy under the Dalai Lamas. About half of the Tibetan lands were exempted from Lhasa's administrative rule and annexed into neighboring Chinese provinces, although most were only nominally subordinated to Beijing.[17]

By the 1860s, Qing "rule" in Tibet had become more theory than fact, given the weight of Qing's domestic and foreign-relations burdens.[18] In 1890, the Qing and Britain signed the Anglo-Chinese Convention Relating to Sikkim and Tibet, which Tibet disregarded since it was for "Lhasa alone to negotiate with foreign powers on Tibet's behalf".[11] The British concluded in 1903 that Chinese suzerainty over Tibet was a "constitutional fiction",[19] and proceeded to invade Tibet in 1903–04. The Qing began taking steps to reassert control,[20] then invaded Lhasa in 1910. In the 1907 Anglo-Russian Convention, Britain and Russia recognized the Qing as suzerain of Tibet and pledged to abstain from Tibetan affairs, thus fixing the suzerainty status in an international document.[21] After the Qing dynasty was overthrown during the Xinhai revolution of 1911, the amban delivered a letter of surrender to the 13th Dalai Lama in the summer of 1912.[11] The Dalai Lama expelled the amban and Chinese military from Tibet, then all Chinese people, after reasserting Tibet's independence on 13 February 1913.[22]

History[]

1641-1717[]

Güshi Khan of the Khoshut in 1641 overthrew the prince of Tsang and helped reunite the regions of Tibet under the 5th Dalai Lama as the highest spiritual and political authority in Tibet.[23] A governing body known as the Ganden Phodrang was established, while Güshi Khan remained personally devoted to the Dalai Lama.[24]

In 1653, the Dalai Lama travelled to Beijing on a state visit, and was received as an equal to the Qing Emperor. At that time, the Dalai Lama was "recognized as the spiritual authority of the Qing Empire",[25] and the "priest" relationship with Qing began. The time of the 5th Dalai Lama, also known of as "the Great Fifth", was a period of rich cultural development.

Decades earlier, Hongtaiji, the founder of the Qing dynasty, had insulted the Mongols for believing in Tibetan Buddhism.[26]

With Güshi Khan, who founded the Khoshut Khanate as a largely uninvolved overlord, the 5th Dalai Lama conducted foreign policy independently of the Qing, on the basis of his spiritual authority amongst the Mongolians. He acted as a mediator between Mongol tribes, and between the Mongols and the Qing Kangxi Emperor. The Dalai Lama would assign territories to Mongol tribes, and these decisions were routinely confirmed by the Emperor.

In 1674, the Emperor asked the Dalai Lama to send Mongolian troops to help suppress Wu Sangui's Revolt of the Three Feudatories in Yunnan. The Dalai Lama refused to send troops, and advised Kangxi to resolve the conflict in Yunnan by dividing China with Wu Sangui. The Dalai Lama openly professed neutrality but he exchanged gifts and letters with Wu Sangui during the war further deepening the Qing's suspicions and angering them against the Dalai Lama.[27][28][29][30][31] This was apparently a turning point for the Emperor, who began to deal with the Mongols directly, rather than through the Dalai Lama.[32]

The Dalai Lama's Ganden Phodrang government formalized the frontier between Tibet and China in 1677, with Kham ascribed to Tibet's authority.[33]

The 5th Dalai Lama died in 1682. His regent, Desi Sangye Gyatso, concealed his death and continued to act in his name. In 1688, Galdan Boshugtu Khan of the Khoshut defeated the Khalkha Mongols and went on to battle Qing forces. This contributed to the loss of Tibet's role as mediator between the Mongols and the Emperor. Several Khalkha tribes formally submitted directly to Kangxi. Galdan retreated to Dzungaria. When Sangye Gyatso complained to Kangxi that he could not control the Mongols of Kokonor in 1693, Kangxi annexed Kokonor, giving it the name it bears today, Qinghai. He also annexed Tachienlu in eastern Kham at this time. When Kangxi finally destroyed Galdan in 1696, a Qing ruse involving the name of the Dalai Lama was involved; Galdan blamed the Dalai Lama for his ruin, still not aware of his death fourteen years earlier.[34]

About this time, some Dzungars informed the Kangxi Emperor that the 5th Dalai Lama had long since died. He sent envoys to Lhasa to inquire. This prompted Sangye Gyatso to make Tsangyang Gyatso, the 6th Dalai Lama, public. He was enthroned in 1697.[35] Tsangyang Gyatso enjoyed a lifestyle that included drinking, the company of women, and writing poetry[14][36] In 1702, he refused to take the vows of a Buddhist monk. The regent, under pressure from the Emperor and Lhazang Khan of the Khoshut, resigned in 1703.[35] In 1705, Lhazang Khan used the sixth Dalai Lama's lifestyle as excuse to take control of Lhasa. The regent Sanggye Gyatso, who had allied himself with the Dzungar Khanate, was murdered, and the Dalai Lama was sent to Beijing. He died on the way, near Kokonor, ostensibly from illness but leaving lingering suspicions of foul play.

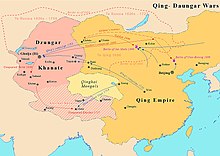

Lhazang Khan appointed a pretender Dalai Lama who was not accepted by the Gelugpa school. The Dalai Lama's incarnation Kelzang Gyatso, 7th Dalai Lama, was discovered near Kokonor. Three Gelug abbots of the Lhasa area[37] appealed to the Dzungar Khanate, which invaded Tibet in 1717, deposed Lhazang Khan's pretender to the position of Dalai Lama, and killed Lhazang Khan and his entire family.[38] The Dzungars then proceeded to loot, rape and kill throughout Lhasa and its environs. They also destroyed a small Chinese force in the Battle of the Salween River, which the Emperor had sent to clear traditional trade routes.[39]

Qing forces arrive in Tibet[]

In response to the Dzungar occupation of Tibet, a joint force of Tibetans and Chinese, sent by the Kangxi Emperor, responded. The Tibetan forces were under Polhanas (also spelled Polhaney) of central Tsang, and Kangchennas (also spelled Gangchenney), the governor of Western Tibet.[40][41] The Dzungars were expelled from Tibet in 1720. They brought Kelzang Gyatso with them from Kumbum to Lhasa and he was enthroned as the 7th Dalai Lama.[42][43]

At that time, a Qing protectorate in Tibet (described by Stein as "sufficiently mild and flexible to be accepted by the Tibetan government") was initiated with a garrison at Lhasa. The area of Kham east of the Dri River (Jinsha River—Upper Yangtze) was annexed to Sichuan in 1726-1727 through a treaty.[24][38][44] In 1721, the Qing expanded their protectorate in Lhasa with a council (the Kashag) of three Tibetan ministers, headed by Kangchennas. A Khalkha prince was made amban, the official representative of Qing in Tibet. Another Khalkha directed the military. The Dalai Lama's role at this time may have been purely symbolic in China's eyes, but it wasn't to the Dalai Lama nor to the Ganden Phodrang government[45] or the Tibetan people, who viewed the Qing as a "patron". The Dalai Lama was also still highly influential because of the Mongols' religious beliefs.[46]

The Qing came as patrons of the Khoshut, liberators of Tibet from the Dzungar, and supporters of the Dalai Lama Kelzang Gyatso, but when they tried to replace the Khoshut as rulers of Kokonor and Tibet, they earned the resentment of the Khoshut and also the Tibetans of Kokonor. , a grandson of Güshi Khan, led a rebellion in 1723, when 200,000 Tibetans and Mongols attacked Xining. Central Tibet did not support the rebellion.[citation needed] Polhanas is said to have blocked the rebels' retreat from Qing retaliation. The rebellion was brutally suppressed.[47]

Green Standard Army troops were garrisoned at multiple places such as Lhasa, Batang, Dartsendo, Lhari, Chamdo, and Litang, throughout the Dzungar war.[48] Green Standard troops and Manchu Bannermen were both part of the Qing force that fought in Tibet in the war against the Dzungars.[49] It was said that the Sichuan commander Yue Zhongqi (a descendant of Yue Fei) entered Lhasa first when the 2,000 Green Standard soldiers and 1,000 Manchu soldiers of the "Sichuan route" seized Lhasa.[50] According to Mark C. Elliott, after 1728 the Qing used Green Standard troops to man the garrison in Lhasa rather than Bannermen.[51] According to Evelyn S. Rawski, both Green Standard Army and Bannermen made up the Qing garrison in Tibet.[52] According to Sabine Dabringhaus, Green Standard Chinese soldiers numbering more than 1,300 were stationed by the Qing in Tibet to support the 3,000-strong Tibetan army.[53]

1725-1761[]

The Kangxi Emperor was succeeded by the Yongzheng Emperor in 1722. In 1725, amidst a series of Qing transitions reducing Qing forces in Tibet and consolidating control of Amdo and Kham, Kangchennas received the title of Prime Minister. The Emperor ordered the conversion of all Nyingma to Gelug. This persecution created a rift between Polhanas, who had been a Nyingma monk, and Kangchennas. Both of these officials, who represented Qing interests, were opposed by the Lhasa nobility, who had been allied with the Dzungars and were anti-Qing. They killed Kangchennas and took control of Lhasa in 1727, and Polhanas fled to his native Ngari. Polhanas gathered an army and retook Lhasa in July 1728 against opposition from the Lhasa nobility and their allies.[54]

Qing troops arrived in Lhasa in September, and punished the anti-Qing faction by executing entire families, including women and children. The Dalai Lama was sent to Lithang Monastery[55] in Kham. The Panchen Lama was brought to Lhasa and was given temporal authority over central Tsang and western Ngari Prefecture, creating a territorial division between the two high lamas that was to become a long-lasting feature of Chinese policy toward Tibet. Two ambans were established in Lhasa, with increased numbers of Qing troops. Over the 1730s, Qing troops were again reduced, and Polhanas gained more power and authority. The Dalai Lama returned to Lhasa in 1735, but temporal power remained with Polhanas. The Qing found Polhanas to be a loyal agent and an effective ruler over a stable Tibet, so he remained dominant until his death in 1747.[54]

The Qing are said to have made the region of Amdo into the province of Qinghai in 1724,[38] and a treaty of 1727[24] led to the incorporation of eastern Kham into neighbouring Chinese provinces in 1728.[56] The Qing government sent a resident commissioner (amban) to Lhasa. A stone monument regarding the boundary between Tibet and neighbouring Chinese provinces, agreed upon by Lhasa and Beijing in 1726, was placed atop a mountain, and survived into at least the 19th century.[57] This boundary, which was used until 1865, delineated the Dri River in Kham as the frontier between Tibet and Qing China.[24][failed verification] Territory east of the boundary was governed by Tibetan chiefs who were answerable to China.[58]

Polhanas' son Gyurme Namgyal took over upon his father's death in 1747. The ambans became convinced that he was going to lead a rebellion, so they assassinated him independently from Beijing's authority.[14] News of the murders leaked out and an uprising broke out in the city during which the residents of Lhasa avenged the regent's death by killing both ambans.

The Dalai Lama stepped in and restored order in Lhasa, while it was thought that further uprisings would result in harsh retaliation from China.[14] The Qianlong Emperor (Yongzheng's successor) sent a force of 800, which executed Gyurme Namgyal's family and seven members of the group that allegedly killed the ambans.

Temporal power was reasserted by the Dalai Lama in 1750. But the Qing Emperor was said to have re-organized the Tibetan government again and appointed new ambans.[59] These ambans or commissioners were not only unable to take charge, they were also kept uninformed. This reduced the post of the Residential Commissioner in Tibet to name only".[56] The number of soldiers in Tibet was kept at about 2,000. The defensive duties were partly helped out by a local force which was reorganized by the amban, and the Tibetan government continued to manage day-to-day affairs as before. The Emperor reorganized the Kashag to have four Kalöns in it.[60] He also used Tibetan Buddhist iconography to try and bolster support among Tibetans, whereby six thangkas portrayed the Qing Emperor as Manjuśrī and China's Tibetan records of the time are said to have referred to him by that name.[38][61]

The 7th Dalai Lama died in 1757. Afterwards, an assembly of lamas decided to institute the office of regent, to be held by an incarnate lama "until the new Dalai Lama attained his majority and could assume his official duties". The Seventh Demo, , was selected unanimously. The 8th Dalai Lama, Jamphel Gyatso, was born in 1758 in Tsang. The Panchen Lama helped in the identification process, while Jampal Gyatso was recognized in 1761, then brought to Lhasa for his enthronement, presided over by the Panchen Lama, in 1762.[62]

1779-1793[]

In 1779, the 6th Panchen Lama, fluent also in Hindi and Persian and well disposed to both Catholic missionaries in Tibet and East India Company agents in India,[citation needed] was invited to Peking for the celebration of the Emperor's 70th birthday.[63][64] The "priest and patron" relationship between Tibet and Qing China was underscored by Emperor prostrating "to his spiritual father".[65][66] In the final stages of his visit, after instructing the Emperor, the Panchen Lama contracted smallpox and died in 1780 in Beijing.

The following year, the 8th Dalai Lama assumed political power in Tibet. Problematic relations with Nepal led in 1788 to Gorkha Kingdom invasions of Tibet, sent by Bahadur Shah, the Regent of Nepal. Again in 1791, Shigatse was occupied by the Gorkas as was the great Tashilhunpo Monastery, the seat of the Panchen Lamas which was sacked and destroyed.

During the first incursion, the Qing Manchu amban in Lhasa spirited away to safety both the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama,[verification needed] but otherwise made no attempt to defend the country, though urgent dispatches to Beijing warned that alien powers had designs on the region, and threatened Qing Manchu interests.[67] At that time, the Qing army found that the Nepalese forces had melted away, and no fighting was necessary. After the second Gorka incursion in 1791, another force of Manchus and Mongols joined by a strong contingents of Tibetan soldiers (10,000 of 13,000) supplied by local chieftains, repelled the invasion and pursued the Gorkhas to the Kathmandu Valley. Nepal conceded defeat and returned all the treasure they had plundered.[63][68]

The Qianlong emperor was disappointed with the results of his 1751 decree and the performance of the ambans. Another decree followed, contained in the "Twenty-Nine Article Imperial Ordinance of 1793". It was designed to enhance the ambans' status, and ordered them to control border inspections, and serve as conduits through which the Dalai Lama and his cabinet were to communicate.

The same 29-article decree attempted to institute the Golden Urn system[69] which contradicted the traditional Tibetan method of locating and recognizing incarnate lamas.

According to Warren Smith, the 29-article decree's directives were either never fully implemented, or quickly discarded, as the Qing were more interested in a symbolic gesture of authority than actual sovereignty. The relationship between Qing and Tibet was one between states, or between an empire and a semi-autonomous state.[70] The 29-article decree attempted to elevate ambans above the Kashag and above the regents in regards to Tibetan political affairs. The decree attempted to prohibit the Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama from petitioning the Chinese Emperor directly whereas petitions were decreed to pass through the ambans. The ambans were to take control of Tibetan frontier defense and foreign affairs. Tibetan authorities' foreign correspondence, even with the Mongols of Kokonor (present-day Qinghai), were to be approved by the ambans, whom were decreed as commanders of the Qing garrison, and the Tibetan army whose strength was set at 3000 men. Trade was also decreed as restricted and travel documents were to be issued by the ambans. The ambans were to review all judicial decisions. The Tibetan currency, which had been the source of trouble with Nepal, was to be taken under Beijing's supervision.[71]

The 29-article decree also attempted to control the traditional methods used to recognize and enthrone both the incarnate Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama, by means of a lottery administered by the ambans in Lhasa. The Emperor wanted to control the recognition process of incarnate lamas because the Gelug school of the Dalai Lamas was the official religion of his Qing court.[72] Another purpose was to have the Mongol grand-lama Qubilγan found in Tibet rather than from the descendants of Genghis Khan.[73] With the decreed lottery system, the names of candidates were written on folded slips of paper which were placed in a golden urn (Mongol altan bumba; Tibetan gser bum:Chinese jīnpíng:金瓶).[74][75] Despite this attempt to further control Tibet's secular and spiritual independence, the Emperor's urn was politely ignored while traditional recognition processes continued unchanged.[76] At times, the selection was approved after the fact by the Emperor.[77] An exception was said to be in the mid-19th century, when Qing support was needed against foreign and Nepalese encroachment.[75] The 11th Dalai Lama was selected by the golden urn method.[77] while the 12th Dalai Lama was recognized by traditional Tibetan methods, but it was said he was "confirmed" by the lottery,[78][79] while there was an open pretense that the lottery was used for the 10th Dalai Lama, when it was not used at all.[80]

19th century[]

In 1837, a minor Kham chieftain Gompo Namgyal, of Nyarong, began expanding his control regionally and launched offensives against the Hor States, Chiefdom of Lithang, Kingdom of Derge, the Kingdom of Chakla and Chiefdom of Bathang.[33][24] Qing China sent troops in against Namgyal which were defeated in 1849,[81] and additional troops were not dispatched. Qing military posts were present along the historic trading route between Beijing and Lhasa, but "did not have any authority over the native chiefs".[24] By 1862, Namgyal blocked trade routes from China to Central Tibet, and sent troops into China.[33]

The kingdom of Derge and another had appealed to both the Lhasa and the Qing Manchu governments for help against Namgyal. During the , the Tibetan authorities sent an army in 1863, and defeated Namgyal then killed him at his Nyarong fort by 1865. Afterward, Lhasa asserted its authority over parts of northern Kham and established the to govern.[33][81] Lhasa reclaimed Nyarong, Degé and the Hor States north of Nyarong. China recalled their forces.[81]

Nepal was a tributary state to China from 1788 to 1908.[82][83] In the Treaty of Thapathali signed in 1856 that concluded the Nepalese-Tibetan War, Tibet and Nepal agreed to "regard the Chinese Emperor as heretofore with respect."[84] Michael van Walt van Praag, legal advisor to the 14th Dalai Lama,[85] claims that 1856 treaty provided for a Nepalese mission, namely Vakil, in Lhasa which later allowed Nepal to claim a diplomatic relationship with Tibet in its application for United Nations membership in 1949.[86] However, the status of Nepalese mission as diplomatic is disputed[87] and the Nepalese Vakils stayed in Tibet until the 1960s when Tibet had been occupied by the Peoples Republic of China for more than a decade.[88][89]

In 1841, the Hindu Dogra dynasty attempted to establish their authority on Ü-Tsang but were defeated in the Sino-Sikh War (1841–1842).

In the mid-19th century, arriving with an amban, a community of Chinese troops from Sichuan that had married Tibetan women settled down in the Lubu neighborhood of Lhasa, where their descendants established a community and assimilated into Tibetan culture.[90] Another community, Hebalin, was where Chinese Muslim troops and their wives and offspring lived.[91]

In 1879, the 13th Dalai Lama was enthroned, but did not assume full temporal control until 1895, after the (tshongs 'du rgyas 'dzom) unanimously called for him to assume power. Before that time, the British Empire increased their interest in Tibet, and a number of Indians entered the region, first as explorers and then as traders. The British sent a mission with a military escort through Sikkim in 1885, whose entry was refused by Tibet and the British withdrew. Tibet then organized an army to be stationed at the border, led by Dapon Lhading (mda' dpon lha sding, d.u.) and Tsedron Sonam Gyeltsen (rtse mgron bsod nams rgyal mtshan, d.u.) with soldiers from southern Kongpo and those from Kham's . At a pass between Sikkim and Tibet, which Tibet considered a part of Tibet, the British attacked in 1888.

Following the attack, the British and Chinese signed the 1890 Anglo-Chinese Convention Relating to Sikkim and Tibet,[92] which Tibet disregarded as it did "all agreements signed between China and Britain regarding Tibet, taking the position that it was for Lhasa alone to negotiate with foreign powers on Tibet's behalf".[11][93] Qing China and Britain had also concluded an earlier treaty in 1886, the "Convention Relating to Burmah and Thibet"[94] as well as a later treaty in 1893.[95] Regardless of those treaties, Tibet continued to bar British envoys from its territory.

Then in 1896, the Qing Governor of Sichuan attempted to gain control of the Nyarong valley in Kham during a military attack led by . The Dalai Lama circumvented the amban and a secret mission led by Sherab Chonpel (shes rab chos 'phel, d.u.) was sent directly to Beijing with a demand for the withdrawal of Chinese forces. The Qing Guangxu Emperor agreed, and the "territory was returned to the direct rule of Lhasa".[11]

Lhasa, 1900-1909[]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

At the beginning of the 20th century the British Empire and Russian Empires were competing for supremacy in Central Asia. During "the Great Game", a period of rivalry between Russia and Britain, the British desired a representative in Lhasa to monitor and offset Russian influence.

Years earlier, the Dalai Lama had developed an interest in Russia through his debating partner, Buriyat Lama Agvan Dorjiev.[11] Then in 1901, Dorjiev had delivered letters from Tibet to the Tzar, namely a formal letter of appreciation from the Dalai Lama, and another from the Kashak directly soliciting support against the British.[11] Dorjiev's journey to Russia was seen as a threat by British interests in India, despite Russian statements they would not intervene. After realizing the Qing lacked any real authority in Tibet,[11] a British expedition was dispatched in 1904, officially to resolve border disputes between Tibet and Sikkim. The expedition quickly turned into an invasion which captured Lhasa.

For the first time and in response to the invasion, the Chinese foreign ministry asserted that China was sovereign over Tibet, the first clear statement of such a claim.[96]

Before the British invasion force arrived in Lhasa, the 13th Dalai Lama escaped to seek alliances for Tibet. The Dalai Lama travelled first to Mongolia and requested help from Russia against China and Britain, and learned in 1907 that Britain and Russia signed a non-interference in Tibet agreement. This essentially removed Tibet from the so-called "Great Game". The Dalai Lama received a dispatch from Lhasa, and was about to return there from Amdo in the summer of 1908 when he decided to go Beijing instead, where he was received with a ceremony appropriately "accorded to any independent sovereign", as witnessed by U.S Ambassador to China William Rockwell.[11] Tibetan affairs were discussed directly with Qing Dowager Empress Cixi, then together with the young Emperor. Cixi died in November 1908 during the state visit, and the Dala Lama performed the funeral rituals.[11] The Dalai Lama also made contacts with Japanese diplomats and military advisors.

The Dalai Lama returned from his search for support against China and Britain to Lhasa in 1909, and initiated reforms to establish a standing Tibetan army while consulting with Japanese advisors. Treaties were signed between the British and the Tibetans, then between China and Britain. The 1904 document was known as the Convention Between Great Britain and Tibet. The main points of the treaty allowed the British to trade in Yadong, Gyantse, and Gartok while Tibet was to pay a large indemnity of 7,500,000 rupees, later reduced by two-thirds, with the Chumbi Valley ceded to Britain until the imdenity was received. Further provisions recognised the Sikkim-Tibet border and prevented Tibet from entering into relations with other foreign powers. As a result, British economic influence expanded further in Tibet, while at the same time Tibet remained under the first claim in 1904 of "sovereignty" by the Qing dynasty of China.[97][verification needed]

The Anglo-Tibetan treaty was followed by a 1906 Convention Between Great Britain and China Respecting Tibet, by which the "Government of Great Britain engages not to annex Tibetan territory or to interfere in the administration of Tibet. The Government of China also undertakes not to permit any other foreign State to interfere with the territory or internal administration of Tibet."[98] Moreover, Beijing agreed to pay London 2.5 million rupees which Lhasa was forced to agree upon in the Anglo-Tibetan treaty of 1904.[99]

As the Dalai Lama had learned during his travels for support, in 1907 Britain and Russia agreed that in "conformity with the admitted principle of the 1904 suzerainty of China over Tibet",[100] (from 1904), both nations "engage not to enter into negotiations with Tibet except through the intermediary of the Chinese Government."[100]

Qing in Kham, 1904-1911[]

Soon after the British invasion of Tibet, the Qing rulers in China were alarmed. They sent the imperial official Feng Quan (凤全) to Kham to begin reasserting Qing control. Feng Quan's initiatives in Kham of land reforms and reductions to the number of monks[81] led to an uprising by monks at a Batang monastery in the Chiefdom of Batang.[33] [81] Tibetan control of the Batang region of Kham in eastern Tibet appears to have continued uncontested following a 1726-1727 treaty.[57] In Batang's uprising, Feng Quan was killed, as were Chinese farmers and their fields were burned.[33] The British invasion through Sikkim triggered a Khampa reaction, where chieftains attacked and French missionaries, Manchu and Han Qing officials, and Christian converts were killed.[101][102] French Catholic missionaries[103] Père Pierre-Marie Bourdonnec and Père Jules Dubernard[104] were killed around the Mekong.[105]

In response, Beijing appointed army commander Zhao Erfeng, the Governor of Xining, to "reintegrate" Tibet into China. Known of as "the Butcher of Kham"[11] Zhao was sent in either 1905 or 1908[106] on a punitive expedition. His troops executed monks[24] destroyed a number of monasteries in Kham and Amdo, and an early form of "sinicization" of the region began.[107][108] Later, around the time of the collapse of the Qing Dynasty, Zhao's soldiers mutinied and beheaded him.[109][110]

Before the collapse of the Qing Empire, the Swedish explorer Sven Hedin returned in 1909 from a three-year-long expedition to Tibet, having mapped and described a large part of inner Tibet. During his travels, he visited the 9th Panchen Lama. For some of the time, Hedin had to camouflage himself as a Tibetan shepherd (because he was European).[111] In an interview following a meeting with the Russian czar he described the situation in 1909 as follows:

"Currently, Tibet is in the cramp-like hands of China´s government. The Chinese realize that if they leave Tibet for the Europeans, it will end its isolation in the East. That is why the Chinese prevent those who wish to enter Tibet. The Dalai Lama is currently also in the hands of the Chinese Government"... "Mongols are fanatics. They adore the Dalai Lama and obey him blindly. If he tomorrow orders them go to war against the Chinese, if he urges them to a bloody revolution, they will all like one man follow him as their ruler. China's government, which fears the Mongols, hooks on to the Dalai Lama."... "There is calm in Tibet. No ferment of any kind is perceptible" (translated from Swedish).[111]

Qing collapse and Tibet independence[]

But in February 1910, the Qing General invaded Tibet during its attempt to gain control of the country. After the Dalai Lama was told he was to be arrested, he escaped from Lhasa to India and remained for three months. Reports arrived of Lhasa's sacking, and the arrests of government officials. He was later informed by letter that Qing China had "deposed" him.[11] [112]

After the Dalai Lama's return to Tibet at a location outside of Lhasa, the collapse of the Qing Dynasty occurred in October 1911. The Qing amban submitted a formal letter of surrender to the Dalai Lama in the summer of 1912.[11]

On 13 February 1913, the Dalai Lama declared Tibet an independent nation, and announced that what he described as the historic "priest and patron relationship" with China had ended.[11] The amban and China's military were expelled, and all Chinese residents in Tibet were given a required departure limit of three years. All remaining Qing forces left Tibet after the Xinhai Lhasa turmoil.

See also[]

- Tibet under Yuan rule

- Sino-Tibetan relations during the Ming dynasty

- Qing dynasty in Inner Asia

- Manchuria under Qing rule

- Mongolia under Qing rule

- Xinjiang under Qing rule

- Taiwan under Qing rule

- Lifan Yuan

- Dzungar–Qing War

- Ganden Phodrang

- Kashag

- List of rulers of Tibet

- List of Qing imperial residents in Tibet

- Chinese expedition to Tibet (1720)

- Chinese expedition to Tibet (1910)

- Tibet (1912–51)

- History of Tibet

- Patron and priest relationship

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Norbu 2001, p. 78: "Professor Luciano Petech, who wrote a definitive history of Sino—Tibetan relations in eighteenth century, terms Tibet's status during this time as a Chinese "protectorate". This may be a fairly value-neutral description of Tibet's status during the eighteenth century..."

- ^ Goldstein, Melvyn C. (April 1995), Tibet, China and the United States (PDF), The Atlantic Council, p. 3 – via Case Western Reserve University: "During that time the Qing Dynasty sent armies into Tibet on four occasions, reorganized the administration of Tibet and established a loose protectorate."

- ^ Dabringhaus, Sabine (2014), "The Ambans of Tibet—Imperial Rule at the Inner Asian Periphery", in Dabringhaus, Sabine; Duindam, Jeroen (eds.), The Dynastic Centre and the Provinces, Agents and Interactions, Brill, pp. 114–126, doi:10.1163/9789004272095_008, ISBN 9789004272095, JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctt1w8h2x3.12

- ^ Di Cosmo, Nicola (2009), "The Qing and Inner Asia: 1636–1800", in Nicola Di Cosmo; Allen J. Frank; Peter B. Golden (eds.), The Cambridge History of Inner Asia: The Chinggisid Age, Cambridge University Press – via ResearchGate

- ^ Szczepanski, Kallie (31 May 2018). "Was Tibet Always Part of China?". ThoughtCo.: "The actual relationship between China and Tibet had been unclear since the early days of the Qing Dynasty, and China's losses at home made the status of Tibet even more uncertain."

- ^ Lamb 1989, pp. 2–3: "From the outset, it became apparent that a major problem lay in the nature of Tibet's international status. Was Tibet part of China? Neither the Tibetans nor the Chinese were willing to provide a satisfactory answer to this question."

- ^ Sperling 2004, p. ix: "The status of Tibet is at the core of the dispute, as it has been for all parties drawn into it over the past century. China maintains that Tibet is an inalienable part of China. Tibetans maintain that Tibet has historically been an independent country. In reality, the conflict over Tibet's status has been a conflict over history."

- ^ Sperling 2004, p. x.

- ^ Mehra 1974, p. 182–183: The statement of Tibetan claims at the 1914 Simla Conference read: "Tibet and China have never been under each other and will never associate with each other in future. It is decided that Tibet is an independent state."

- ^ Szczepanski, Kallie (31 May 2018). "Was Tibet Always Part of China?". ThoughtCo.: "According to Tibet, the "priest/patron" relationship established at this time [1653] between the Dalai Lama and Qing China continued throughout the Qing Era, but it had no bearing on Tibet's status as an independent nation."

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Tsering Shakya, "The Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Tubten Gyatso" Treasury of Lives, accessed May 11, 2021.

- ^ Fitzherbert & Travers 2020: '[From 1642], as a Buddhist government, the Ganden Phodrang’s choice to relinquish... the military defence of its territory to foreign troops, first Mongol and later Sino-Manchu, in the framework of “patron-preceptor” (mchod yon) relationships, created a structural situation involving long-term contacts and cooperation between Tibetans and "foreign" military cultures.'

- ^ Goldstein, Melvyn C. (April 1995), Tibet, China and the United States (PDF), The Atlantic Council, p. 3 – via Case Western Reserve University

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Szczepanski, Kallie (31 May 2018). "Was Tibet Always Part of China?". ThoughtCo.

- ^ Emblems of Empire: Selections from the Mactaggart Art Collection, by John E. Vollmer, Jacqueline Simcox, p154

- ^ Central Tibetan Administation 1994, p. 26: "The ambans were not viceroys or administrators, but were essentially ambassadors appointed to look after Manchu interests, and to protect the Dalai Lama on behalf of the emperor."

- ^ Klieger, P. Christiaan (2015). Greater Tibet: An Examination of Borders, Ethnic Boundaries, and Cultural Areas. p. 71. ISBN 9781498506458.

- ^ Revolution and Its Past: Identities and Change in Modern Chinese History, by R. Keith Schoppa, p341

- ^ International Commission of Jurists (1959), p. 80.

- ^ India Quarterly (volume 7), by Indian Council of World Affairs, p120

- ^ Klieger, P. Christiaan (2015). Greater Tibet: An Examination of Borders, Ethnic Boundaries, and Cultural Areas. p. 74. ISBN 9781498506458.

- ^ Irina Garri, The rise of the Five Hor States of Northern Kham. Religion and politics in the Sino-Tibetan borderlands, "Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines", No. 51, 2020. Posted online 09 December 2020.

- ^ René Grousset, The Empire of the Steppes, New Brunswick 1970, p. 522

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Irina Garri, "The rise of the Five Hor States of Northern Kham. Religion and politics in the Sino-Tibetan borderlands", Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines, No 51, 2020, posted online 09 December 2020

- ^ Szczepanski, Kallie (31 May 2018). "Was Tibet Always Part of China?". ThoughtCo.: "The Dalai Lama made a state visit to the Qing Dynasty's second Emperor, Shunzhi, in 1653. The two leaders greeted one another as equals; the Dalai Lama did not kowtow. Each man bestowed honors and titles upon the other, and the Dalai Lama was recognized as the spiritual authority of the Qing Empire."

- ^ Waley-Cohen, Joanna (1998). "Religion, War, and Empire-Building in Eighteenth-Century China" (PDF). International History Review. 20 (2): 340. doi:10.1080/07075332.1998.9640827.

- ^ Wellens, Koen (2011). Religious Revival in the Tibetan Borderlands: The Premi of Southwest China. University of Washington Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0295801551.

- ^ Dai, Yingcong (2011). The Sichuan Frontier and Tibet: Imperial Strategy in the Early Qing. University of Washington Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0295800707.

- ^ Ya, Hanzhang; Chen, Guansheng; Li, Peizhuan (1994). Biographies of the Tibetan spiritual leaders Panchen Erdenis. Foreign Languages Press. p. 63. ISBN 7119016873.

- ^ Zheng, Shan (2001). A history of development of Tibet. Foreign Languages Press. p. 229. ISBN 7119018655.

- ^ Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko: (the Oriental Library), Issues 56–59. Tôyô Bunko. 1998. p. 135.

- ^ Smith 1996, pp. 116–7

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Jann Ronis, "An Overview of Kham (Eastern Tibet) Historical Polities", The University of Virginia

- ^ Smith 1996, pp. 117–120

- ^ Jump up to: a b Smith 1996, pp. 120–1

- ^ Karenina Kollmar-Paulenz, Kleine Geschichte Tibets, München 2006, pp. 109–122.

- ^ Mullin 2001, p. 285

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Rolf Alfred Stein (1972). Tibetan Civilization. Stanford University Press. pp. 85–88. ISBN 978-0-8047-0901-9.

- ^ Mullin 2001, p. 288

- ^ Mullin 2001, p. 290

- ^ Smith 1996, p. 125

- ^ Richardson, Hugh E. (1984). Tibet and its History. Second Edition, Revised and Updated, pp. 48–9. Shambhala. Boston & London. ISBN 0-87773-376-7 (pbk)

- ^ Schirokauer, 242

- ^ Smith 1996, p. 127.

- ^ Melvyn C. Goldstein (18 June 1991). A History of Modern Tibet, 1913–1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State. University of California Press. pp. 328 ff. ISBN 978-0-520-91176-5.

- ^ Smith 1996, p. 126

- ^ Smith 1996, pp. 125–6

- ^ Wang 2011, p. 30.

- ^ Dai 2009, p. 81.

- ^ Dai 2009, pp. 81–2.

- ^ Elliott 2001, p. 412.

- ^ Rawski 1998, p. 251.

- ^ Dabringhaus 2014, p. 123.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Smith 1996, pp. 126–131

- ^ Mullin 2001, p. 293

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wang Lixiong, Reflections on Tibet Archived 2006-06-20 at the Wayback Machine, "New Left Review" 14, March–April 2002:'"Tibetan local affairs were left to the willful actions of the Dalai Lama and the shapes [Kashag members]", he said. "The Commissioners were not only unable to take charge, they were also kept uninformed. This reduced the post of the Residential Commissioner in Tibet to name only.'

- ^ Jump up to: a b Huc, Évariste Régis (1852), Hazlitt, William (ed.), Travels in Tartary, Thibet, and China during the Years 1844–5–6, Vol. I, London: National Illustrated Library, p. 123

|volume=has extra text (help). - ^ Chapman, F. Spencer. (1940). Lhasa: The Holy City, p. 135. Readers Union Ltd., London.

- ^ Smith 1996, pp. 191–2

- ^ Wang 2001, pp. 170–3

- ^ Shirokauer, A Brief History of Chinese Civilization, Thompson Higher Education, (c) 2006, 244

- ^ Derek Maher, "The Eighth Dalai Lama, Jampel Gyatso" Treasury of Lives, accessed May 17, 2021

- ^ Jump up to: a b Frederick W. Mote, Imperial China 900–1800, Harvard University Press, 2003 p.938.

- ^ The journey and meeting is described in Kate Teltscher, The high road to China: George Bogle, the Panchen Lama and the first British expedition to Tibet, Bloomsbury Publishing 2007, pp. 208–226.

- ^ In regard to kowtowing, Shakabpa writes:'As they were leaving, the emperor came to visit the all-seeing Rimpoché. As the Emperor was to remain there for three days, he went to prostrate to his spiritual father at a place called Tungling.' Shakabpa, ibid.p.500.

- ^ Shakabka reads this event as illustrating the Preceptor-Patron relationship between China and Tibet. The Emperor wrote a letter which read: The wheel of doctrine will be turned throughout the world through the powerful scripture foretold to endure as long as the sky. Next year, you will come to honor the day of by birth, enhancing my state of mind. I am enjoying thinking about your swiftly impending arrival. On the way, Panchen Ertini, you will bring about happiness through spreading Buddhism and affecting the welfare of Tibet and Mongolia. I am presently learning the Tibetan language. When we meet directly, I will speak with you with great joy.' W. D. Shakabpa, One hundred thousand moons, trans. Derek F. Maher, BRILL, 2010, p. 497.

- ^ Frederick W. Mote, Imperial China, p.938.

- ^ Teltscher 2006, pp. 244–246

- ^ Derek Maher in W. D. Shakabpa, One hundred thousand moons, translated with a commentary by Derek F. Maher, BRILL, 2010 pp.486–7.

- ^ Smith 1996, p. 137

- ^ Smith 1996, pp. 134–135

- ^ Mullin 2001, p. 358

- ^ Patrick Taveirne,Han-Mongol encounters and missionary endeavors, Leuven University Press, 2004, p.89.

- ^ Goldstein 1989, p.44, n.13

- ^ Jump up to: a b Taveirne,Han-Mongol encounters, p. 89.

- ^ Smith 1996, p. 151

- ^ Jump up to: a b Grunfeld 1996, p. 47

- ^ Smith 1996, p. 140, n. 59

- ^ Mullin 2001, pp. 369–370

- ^ Smith 1996, p. 138

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Yudru Tsomu, "Taming the Khampas: The Republican Construction of Eastern Tibet" Modern China Journal, Vol. 39, No. 3 (May 2013), pp. 319-344

- ^ Ashley Eden, British Envoy and Special Commissioner to Sikkim, dispatch to the Secretary of the Government of Bengal, April 1861, quoted in Taraknath Das, British Expansion in Tibet, p12, saying "Nepal is tributary to China, Tibet is tributary to China, and Sikkim and Bhutan are tributary to Tibet"

- ^ Wang 2001, pp. 239–240

- ^ Treaty Between Tibet and Nepal, 1856, Tibet Justice Center

- ^ History of Tibet Justice Center

- ^ Walt van Praag, Michael C. van. The Status of Tibet: History, Rights and Prospects in International Law, Boulder, 1987, pp. 139–40

- ^ Grunfeld 1996, p257

- ^ Li, T.T., The Historical Status of Tibet, King's Crown Press, New York, 1956

- ^ Sino-Nepal Agreement of 1956

- ^ Yeh 2009, p. 60.

- ^ Yeh 2013, p. 283.

- ^ Tibet Justice Center – Legal Materials on Tibet – Treaties and Conventions Relating to Tibet – Convention Between Great Britain and China Relating to Sikkim and Tibet (1890) ...

- ^ Powers 2004, pg. 80

- ^ Tibet Justice Center – Legal Materials on Tibet – Treaties and Conventions Relating to Tibet – Convention Relating to Burmah and Thibet (1886)

- ^ Project South Asia

- ^ Michael C. Van Walt Van Praag. The Status of Tibet: History, Rights and Prospects in International Law, p. 37. (1987). London, Wisdom Publications. ISBN 978-0-8133-0394-9.

- ^ Alexandrowicz-Alexander, Charles Henry (1954). "The Legal Position of Tibet". The American Journal of International Law. 48 (2): 265–274. doi:10.2307/2194374. ISSN 0002-9300. JSTOR 2194374.

- ^ Convention Between Great Britain and China Respecting Tibet (1906)

- ^ Melvyn C. Goldstein, Tibet, China and the United States: Reflections on the Tibet Question. Archived 2006-11-06 at the Wayback Machine, 1995

- ^ Jump up to: a b Convention Between Great Britain and Russia (1907)

- ^ Bray, John (2011). "Sacred Words and Earthly Powers: Christian Missionary Engagement with Tibet". The Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan. fifth series. Tokyo: John Bray & The Asian Society of Japan (3): 93–118. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ Tuttle, Gray (2005). Tibetan Buddhists in the Making of Modern China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 45. ISBN 0231134460. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Mission-Thibet (fr)

- ^ Royal Horticultural Society (Great Britain) (1996). The Garden, Volume 121. Published for the Royal Horticultural Society by New Perspectives Pub. Ltd. p. 274. Retrieved 2011-06-28.(Original from Cornell University)

- ^ Eric Teichman (1922). Travels of a consular officer in eastern Tibet: together with a history of the relations between China, Tibet and India. University Press. p. 248. ISBN 9780598963802. Retrieved 2011-06-28.(Original from the University of California)

- ^ FOSSIER Astrid, Paris, 2004 "L’Inde des britanniques à Nehru : un acteur clé du conflit sino-tibétain."

- ^ Karenina Kollmar-Paulenz, Kleine Geschichte Tibets, München 2006, p. 140f

- ^ Goldstein 1989, p. 46f

- ^ Hilton 2000, p. 115

- ^ Goldstein 1989, p. 58f

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Swedish newspaper Fäderneslandet, 1909-01-16

- ^ Goldstein 1989, p. 49ff

Bibliography[]

- Tibet, Proving Truth from Facts, Department of Information and International Relations, Central Tibetan Administration, 1994

- Tibet: Proving Truth from Facts, Central Tibetan Administration, 1 January 1996.

- Fitzherbert, Solomon George; Travers, Alice (2020), "Introduction: The Ganden Phodrang's Military Institutions and Culture between the 17th and the 20th Centu-ries, at a Crossroads of Influences", Revue d'Etudes Tibétaines, CNRS, 53: 7–28

- Lamb, Alastair (1989), Tibet, China & India, 1914-1950: A history of imperial diplomacy, Roxford Books, ISBN 9780907129035

- Mehra, Parshotam (1974), The McMahon Line and After: A Study of the Triangular Contest on India's North-eastern Frontier Between Britain, China and Tibet, 1904-47, Macmillan, ISBN 9780333157374 – via archive.org

- Norbu, Dawa (2001), China's Tibet Policy, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-136-79793-4

- Smith, Warren (1996), Tibetan Nation: A History of Tibetan Nationalism And Sino-Tibetan Relations, Avalon Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8133-3155-3

- Sperling, Elliot (2004), The Tibet-China Conflict: History and Polemics (PDF), East-West Center Washington, ISBN 978-1-932728-12-5

- States and territories established in 1720

- States and territories disestablished in 1912

- Qing dynasty

- History of Tibet

- 18th century in Tibet

- 19th century in Tibet

- 20th century in Tibet

- 1912 disestablishments in Asia

- 1720 establishments in China

- China–Tibet relations