Vietnamese people

Young Vietnamese ladies in áo dài during the event | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 89 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 82,085,826 (2019)[1] | |

| 2,162,610 (2018)[2] | |

| 400,000–1,000,000[3][4][5] | |

| 448,053[6][better source needed] | |

| ~400,000[7][8] | |

| 294,798 (2016)[9] | |

| 243,734 (2021)[a][10] | |

| 240,514[11] | |

| 224,518 (2020)[12] | |

| 188,000 (2019)[13] | |

| 13,954[14]–150,000[15] | |

| 122,000[16] | |

| 100,000[17]–500,000[18] | |

| 60,000[19]–200,000[20] | |

| 80,000[21] | |

| 25,000–60,000[22][23] | |

| 50,000–100,000[24] | |

| 45,000[25] | |

| 10,000[26]–50,000[27] | |

| 36,205[b][28] | |

| 27,600[citation needed] | |

| 27,366 (2020)[29] | |

| 23,488 (2019)[30][better source needed] | |

| 20,676 (2020)[31] | |

| ~20,000 (2018)[32] | |

| 20,000[33] | |

| 20,000[34][35][36] | |

| 15,953 (2020)[37] | |

| 12,000-15,000[38][39] | |

| 12,051[40] | |

| 12,000 (2012)[41] | |

| ~12,000[42][43] | |

| 5,565[44]–20,000[45] | |

| 10,086 (2018)[46] | |

| ~8,000[47] | |

| 7,304 (2016)[48] | |

| 5,000[49] | |

| 5,000[50] | |

| 3,000[51] | |

| 2,500[52] | |

| Languages | |

| Vietnamese | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Vietnamese folk religion syncretized with Mahayana Buddhism. Minorities of Christians (mostly Roman Catholics) and other groups.[53] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Vietic ethnic groups (Gin, Muong, Chứt, Thổ peoples) | |

The Vietnamese people (Vietnamese: người Việt) or Kinh people (Vietnamese: người Kinh) are a Southeast Asian ethnic group originally native to modern-day Northern Vietnam and South China. The native language is Vietnamese, the most widely spoken Austroasiatic language. Although the Vietnamese language is Austroasiatic in origin, it was heavily sinicized throughout history and its vocabulary was influenced by Chinese.

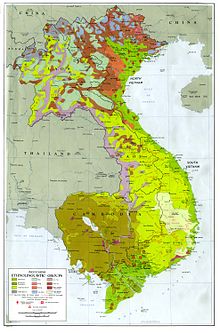

Vietnamese Kinh people account for just over 85.32% of the population of Vietnam in the 2019 census, and are officially known as Kinh people (người Kinh) to distinguish them from the other minority groups residing in the country such as the Hmong, Cham or Muong. The earliest recorded name for the ancient Kinh people in Vietnamese history books is Lạc or Lạc Việt. The Vietnamese are one of the four main groups of Vietic speakers in Vietnam, the others being the Muong, Thổ and Chứt people.

Terminology

Việt

The term "Việt" (Yue) (Chinese: 越; pinyin: Yuè; Cantonese Yale: Yuht; Wade–Giles: Yüeh4; Vietnamese: Việt) in Early Middle Chinese was first written using the logograph "戉" for an axe (a homophone), in oracle bone and bronze inscriptions of the late Shang dynasty (c. 1200 BC), and later as "越".[54] At that time it referred to a people or chieftain to the northwest of the Shang.[55] In the early 8th century BC, a tribe on the middle Yangtze were called the Yangyue, a term later used for peoples further south.[55] Between the 7th and 4th centuries BC Yue/Việt referred to the State of Yue in the lower Yangtze basin and its people.[54][55] From the 3rd century BC the term was used for the non-Chinese populations of south and southwest China and northern Vietnam, with particular ethnic groups called Minyue, Ouyue, Luoyue (Vietnamese: Lạc Việt), etc., collectively called the Baiyue (Bách Việt, Chinese: 百越; pinyin: Bǎiyuè; Cantonese Yale: Baak Yuet; Vietnamese: Bách Việt; "Hundred Yue/Viet"; ).[54][55] The term Baiyue/Bách Việt first appeared in the book Lüshi Chunqiu compiled around 239 BC.[56] By the 17th and 18th centuries AD, educated Vietnamese apparently referred to themselves as người Việt (Viet people) or người nam (southern people).[57]

Kinh

Beginning in the 10th and 11th centuries, a strand of Proto-Viet-Muong with influence from Annamese Middle Chinese started to become what is now the Vietnamese language. Its speakers called themselves the "Kinh" people, meaning people of the "metropolitan" centered around the Red River Delta with Hanoi as its capital. Historic and modern Chữ Nôm scripture classically uses the Han character '京', pronounced "Jīng" in Mandarin, and "Kinh" with Sino-Vietnamese pronunciation. Other variants of Proto-Viet-Muong were driven to the lowlands by the Kinh and were called Trại (寨 Mandarin: Zhài), or "outpost" people," by the 13th century. These became the modern Muong people.[58] According to Victor Lieberman, người Kinh may be a colonial-era term for Vietnamese speakers inserted anachronistically into translations of pre-colonial documents, but literature on 18th century ethnic formation is lacking.[57]

History

Origins and pre-history

The origin of ethnic Vietnamese were Proto-Vietic people who descended from Proto-Austroasiatic people that possibly originated from somewhere in Southern China, Yunnan, the Lingnan, or the Yangtze River, together with the Monic, who settled further to the west and the Khmeric migrated further south. Most archaeologists and linguists, and other specialists like Sinologists and crop experts, believe that they arrived no later than 2000 BC bringing with them the practice of riverine agriculture and in particular the cultivation of wet rice.[59][60][61][62][63] Some linguistic scholars (James Chamberlain, Joachim Schliesinger) suggested that the Vietic-speaking people migrated from southern Red River Delta to the delta itself which originally inhabited by Tai-speakers.[64][65][66][67] However, Michael Churchman found no records of population shifts in Jiaozhi (centered around the Red River Delta) in Chinese sources, indicating that a faily stable population of Austroasiatic speakers, ancestral to modern Vietnamese, inhabited in the delta during the Han-Tang periods.[68] In the 1930s, clusters of Vietic-speaking communities were discovered in the hills of eastern Laos, are believed to be the earliest inhabitants of that region.[69]

According to Vietnamese legend The Tale the Hồng Bàng Clan written in the 15th century, the first Vietnamese descended from the dragon lord Lạc Long Quân and the fairy Âu Cơ. They married and had one hundred eggs, from which hatched one hundred children. Their eldest son ruled as the Hùng king.[70] The Hùng kings were claimed to be descended from the mythical figure Shen Nong.[71]

Early history and Chinese rule

The earliest reference of the proto-Vietnamese or the Vietic in Chinese annals was the Lạc (Chinese: Luo), Lạc Việt, or the Dongsonian,[72] an ancient ethnic group of Mon-Khmer (Austroasiatic) stock occupied the Red River Delta.[73] The Lạc developed the sophisticated metal age Dong Son Culture and the Văn Lang chiefdom, ruled by the semi-mythical Hùng kings.[74] To the south of the Dongsonians was the Sa Huynh Culture of the Austronesian proto-Cham people.[75] Around 400–200 BC, the Lạc came to contact with the Âu Việt Tai people and the Sinitic people from the north.[73] According to a late third or early fourth century AD Chinese chronicle, the leader of the Âu Việt, Thục Phán, conquered Văn Lang and deposed the last Hùng king.[76] Having submissions of Lạc lords, Thục Phán proclaimed himself King An Dương of Âu Lạc kingdom.[74]

In 179 BC, Zhao Tuo, a Chinese general who has established the Nanyue state in modern-day Southern China, annexed Âu Lạc, and began the Sino-Vietic interaction that lasted in a millennium.[77] In 111 BC, the Han Empire conquered Nanyue, brought the Lac Viet region under Han rule.[78] By 2 AD, nearly one million people lived in northern Vietnam and central Vietnam (981,735 people according to Han census).[79] The Han Chinese began conducting their civilizing mission over the local people, which ultimately resulted in a violent uprising of the local Lac people led by Trung sisters in 40s AD.[80][81] The sisters' stronghold was annihilated in 43 AD, the rebelled Lạc lords were butchered, five thousand people were decapitated, and some hundred families were deported to China.[82] After 43 AD, the Han dynasty imposed direct imperial rule over the region. The Lạc Việt elites started adopting Chinese culture, techniques, and life style, while retaining their own customs.[83] Mahayana Buddhism arrived from India via sea routes in the 1st and 2nd centuries, while Taoism and Confucianism made their ways to early Vietnamese society at the same time.[84]

The Han empire declined in the late 2nd century and gave ways to the Three Kingdoms era. Chinese eyewitness reports in 231 stated that "In the two districts of Mê Linh in Jiaozhi and Do Long in Jiuzhen, it is usual for a younger brother to marry the widow of an older brother. Even the local officials cannot prevent it."[85] By the 7th century to 9th century AD, as the Tang Empire ruled over the region, historians such as Henri Maspero proposed that ethnic Vietnamese became separated from other Vietic groups such as the Muong and Chut due to heavier Chinese influences on the Vietnamese.[86] Other argue that a Vietic migration from north central Vietnam to the Red River Delta in the seventh century replaced the original Tai-speaking inhabitants.[87] At least 6 monks from northern Vietnam traveled to China, Srivijaya, India and Sri Lanka during the Tang period.[88] A bronze bell inscription dated 798 inscribes names of 100 female members of a local Buddhist sect that have the middle syllable thị (C. shi) that corresponding to the most common form of name for Vietnamese women.[89] In 816, Liêu Hữu Phương, a native Vietnamese scholar, traveled to Chinese capital Chang'an and passed the Imperial examination.[90] In the mid-9th century, local rebels aided by Nanzhao tore the Tang Chinese rule to nearly collapse.[91] The Tang reconquered the region in 866, causing half of the local rebels to flee into the mountains, which historians believe that was the separation between the Muong and the Vietnamese took at the end of Tang rule in Vietnam.[86][92] In 938, the Vietnamese leader Ngo Quyen who was a native of Thanh Hoa, led Viet forces defeated the Chinese Southern Han armada at Bạch Đằng River and proclaimed himself king, became the first Vietnamese king of the classical period.[93]

Classical and early modern period

Ngo Quyen died in 944 and his kingdom collapsed into chaos and disturbances between 12 Viet warlords and chiefs.[94] In 968, the Việt leader Đinh Bộ Lĩnh united them and established the Đại Việt (Great Việt) kingdom.[95] With assistance of powerful Buddhist monks, Đinh Bộ Lĩnh chose Hoa Lư in the southern edge of the Red River Delta as the capital instead of Tang-era Dai La, adopted Chinese-style imperial titles, coinage, and ceremonies and tried to preserve the T’ang administrative framework.[96] In 979 Dinh Bo Linh was assassinated, and Queen Duong Van Nga married with Dinh's general Le Hoan, appointed him as king. Disturbances in Dai Viet attracted attentions from neighbouring Chinese Song dynasty and Champa Kingdom, but they were defeated by Le Hoan.[97] In 982 the Vietnamese attacked and destroyed Champa's capital Indrapura and Đại Việt was recorded in Arab chronicle Al-Fihrist as the Luqin (Long Biên) kingdom.[98] A Khmer inscription dated 987 records the arrival of Vietnamese merchants (Yawana) in Angkor.[99] Chinese writers, Song Hao, Fan Chengda and , both reported that the Việt "tattooed their foreheads, crossed feet, black teeth, bare feet and blacken clothing."[100]

Successive Vietnamese royal families from the Đinh, Lê, Lý dynasties and Hoa-Chinese ancestry Trần and Hồ dynasties ruled the kingdom peacefully from 968 to 1407. King Lý Thái Tổ (r. 1009–1028) relocated the Vietnamese capital from Hoa Lư to Hanoi, the center of the Red River Delta in 1010.[101] They practiced elitist marriage alliances between clans and nobles in the country. Mahayana Buddhism became state religion, Vietnamese music instruments, dancing and religious worshipping were influenced by both Cham, Indian and Chinese styles,[102] while Confucianism slowly gained attention and influence.[103] The earliest surviving corpus and text in Vietnamese language dated early 12th century, and surviving chữ nôm script inscriptions dated early 13th century.[104]

The Mongol Yuan dynasty unsuccessful invaded Dai Viet in the 1250s and 1280s, though they sacked Hanoi.[105] The Ming dynasty of China conquered Dai Viet in 1406, brought the Vietnamese under Chinese rule for 20 years, before they were driven out by Vietnamese leader Lê Lợi. The Chinese brought several thousands of Vietnamese artisans, skilled workers to China, resettled them in Beijing.[106] During the 15th century, Dai Viet's population skyrocketed from 1.9 million to 4.4 million.[107] The fourth grandson of Lê Lợi, king Lê Thánh Tông (r. 1460–1497), is considered one of the greatest monarchs in Vietnamese history. His reign is recognized for the extensive administrative, military, education, and fiscal reforms he instituted, and a cultural revolution that replaced the old traditional aristocracy with a generation of literati scholars, adopted Confucianism, and transformed a Dai Viet from a Southeast Asian style polity to a bureaucratic state, and flourished. Thánh Tông's forces, armed with gunpowder, overwhelmed the long-term rival Champa in 1471, occupied the Laotian and Lan Na kingdoms in the 1480s.[108]

16th century – Modern period

With the death of Thánh Tông in 1497, the Dai Viet kingdom swiftly declined. Climate extremes, failing crops, regionalism and factionism tore the Vietnamese apart.[109] From 1533 to 1790s, four powerful Vietnamese families: Mạc, Lê, Trịnh and Nguyễn, each ruled on their own domains. In northern Vietnam (Dang Ngoai–outer realm), the Lê kings barely sat on the throne while the Trịnh lords held power of the court. The Mạc controlled northeast Vietnam, Trà Kiệu and sometimes the Cambodian court. The Nguyễn lords ruled the southern polity of Dang Trong (inner realm).[110] Thousands of ethnic Vietnamese migrated south, settled on the old Cham lands.[111] European missionaries and traders from the sixteenth century brought new religion, ideas and crops to the Vietnamese (Annamites). By 1639, there were 82,500 Catholic converts throughout Vietnam. In 1651, Alexandre de Rhodes published a 300-pages catechism in Latin and romanized-Vietnamese (chu quoc ngu) or the Vietnamese alphabet.[112]

The Vietnamese Fragmentation period ended in 1802 as Emperor Gia Long, who was aided by French, Siamese, Malays,... defeated the Tay Son regime and reunited Vietnam. By 1847, the Vietnamese state under Emperor Thieu Tri, ethnic Vietnamese accounted for nearly 80 percent of the country's population (6.3 million people out of 8 million), while rest were Chams, Chinese, and Khmers.[113] This demographic model continues to persist through the French Indochina, Japanese occupation and modern day.

Between 1862 and 1867, the southern third of the country became the French colony of Cochinchina.[114] By 1884, the entire country had come under French rule, with the central and northern parts of Vietnam separated into the two protectorates of Annam and Tonkin. The three Vietnamese entities were formally integrated into the union of French Indochina in 1887.[115][116] The French administration imposed significant political and cultural changes on Vietnamese society.[117] A Western-style system of modern education introduced new humanist values into Vietnam.[118]

The French developed a plantation economy to promote the export of tobacco, indigo, tea and coffee.[119] However, they largely ignored the increasing demands for civil rights and self-government. A nationalist political movement soon emerged, with leaders like Phan Bội Châu, Phan Châu Trinh, Phan Đình Phùng, Emperor Hàm Nghi, and Hồ Chí Minh fighting or calling for independence.[120] This resulted in the 1930 Yên Bái mutiny by the Vietnamese Nationalist Party (VNQDĐ), which the French quashed. The mutiny caused an irreparable split in the independence movement that resulted in many leading members of the organisation becoming communist converts.[121][122][123]

The French maintained full control over their colonies until World War II, when the war in the Pacific led to the Japanese invasion of French Indochina in 1940. Afterwards, the Japanese Empire was allowed to station its troops in Vietnam while permitting the pro-Vichy French colonial administration to continue.[124][125] Japan exploited Vietnam's natural resources to support its military campaigns, culminating in a full-scale takeover of the country in March 1945. This led to the Vietnamese Famine of 1945, which resulted in up to two million deaths.[126][127]

In 1941, the Việt Minh, a nationalist liberation movement based on a Communist Ideology, led by Hồ Chí Minh. The Việt Minh sought independence for Vietnam from France and the end of the Japanese occupation.[128][129] Following the military defeat of Japan and the fall of its puppet Empire of Vietnam in August 1945, anarchy, rioting, and murder were widespread, as Saigon's administrative services had collapsed.[130] The Việt Minh occupied Hanoi and proclaimed a provisional government, which asserted national independence on 2 September.[129]

But as the French were weakened by the German occupation, British-Indian forces and the remaining Japanese Southern Expeditionary Army Group were used to maintain order and to help France reestablish control through the 1945–1946 War in Vietnam.[131] Hồ initially chose to take a moderate stance to avoid military conflict with France, asking the French to withdraw their colonial administrators and for French professors and engineers to help build a modern independent Vietnam.[129] But the Provisional Government of the French Republic did not act on these requests, including the idea of independence, and dispatched the French Far East Expeditionary Corps to restore colonial rule. This resulted in the Việt Minh launching a guerrilla campaign against the French in late 1946.[128][129][132] The resulting First Indochina War lasted until July 1954. The defeat of French colonialists and Vietnamese loyalists in the 1954 battle of Điện Biên Phủ allowed Hồ to negotiate a ceasefire from a favourable position at the subsequent Geneva Conference.[129][133]

The colonial administration was thereby ended and French Indochina was dissolved under the Geneva Accords of 1954. Vietnam was further divided into North and South administrative regions at the Demilitarised Zone, roughly along the 17th parallel north, pending elections scheduled for July 1956.[n 1] A 300-day period of free movement was permitted, during which almost a million northerners, mainly Catholics, moved south, fearing persecution by the communists. This migration was in large part aided by the United States military through Operation Passage to Freedom.[138][139] The partition of Vietnam by the Geneva Accords was not intended to be permanent, and stipulated that Vietnam would be reunited after the elections.[140] But in 1955, the southern State of Vietnam's prime minister, Ngô Đình Diệm, toppled Bảo Đại in a fraudulent referendum organised by his brother Ngô Đình Nhu, and proclaimed himself president of the Republic of Vietnam.[140] At that point the internationally recognised State of Vietnam effectively ceased to exist and was replaced by the Republic of Vietnam in the south—supported by the United States, France, Laos, Republic of China and Thailand—and Hồ's Democratic Republic of Vietnam in the north, supported by the Soviet Union, Sweden,[141] Khmer Rouge, and the People's Republic of China.[140]

On 2 July 1976, North and South Vietnam were merged to form the Socialist Republic of Việt Nam.[142] The war left Vietnam devastated, with the total death toll between 966,000 and 3.8 million.[143][144][145] In its aftermath, under Lê Duẩn's administration, there were no mass executions of South Vietnamese who had collaborated with the US or the defunct South Vietnamese government, confounding Western fears,[146] but up to 300,000 South Vietnamese were sent to reeducation camps, where many endured torture, starvation, and disease while being forced to perform hard labour.[147] The government embarked on a mass campaign of collectivisation of farms and factories.[148] In 1978, in response to the Khmer Rouge government of Cambodia ordering massacres of Vietnamese residents in the border villages in the districts of An Giang and Kiên Giang,[149] the Vietnamese military invaded Cambodia and removed them from power after occupying Phnom Penh.[150] The intervention was a success, resulting in the establishment of a new, pro-Vietnam socialist government, the People's Republic of Kampuchea, which ruled until 1989.[151]

At the Sixth National Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) in December 1986, reformist politicians replaced the "old guard" government with new leadership.[152][153] The reformers were led by 71-year-old Nguyễn Văn Linh, who became the party's new general secretary.[152] He and the reformers implemented a series of free-market reforms known as Đổi Mới ("Renovation") that carefully managed the transition from a planned economy to a "socialist-oriented market economy".[154][155] Though the authority of the state remained unchallenged under Đổi Mới, the government encouraged private ownership of farms and factories, economic deregulation, and foreign investment, while maintaining control over strategic industries.[155][156] The Vietnamese economy subsequently achieved strong growth in agricultural and industrial production, construction, exports, and foreign investment, although these reforms also caused a rise in income inequality and gender disparities.[157][158][159]

Religions

According to the 2019 Census, the religious demographics of Vietnam are as follows:[1]

- 86.32% Vietnamese folk religion or non religious

- 6.1% Catholicism

- 4.79% Buddhism (mainly Mahayana)

- 1.02% Hoahaoism

- 1% Protestantism

- <1% Caodaism

- 0.77 Others

It is worth noting here that the data is highly skewered, as a large majority of Vietnamese may declare themselves atheist, yet practice forms of traditional folk religion or Mahayana Buddhism.[160]

Estimates for the year 2010 published by the Pew Research Center:[161]

- Vietnamese folk religion, 45.3%

- Unaffiliated, 29.6%

- Buddhism, 16.4%

- Christianity, 8.2%

- Other, 0.5%

Diaspora

Originally from northern Vietnam and southern China, the Vietnamese have conquered much of the land belonging to the former Champa Kingdom and Khmer Empire over the centuries. They are the dominant ethnic group in most provinces of Vietnam, and constitute a portion of the population in neighbouring Cambodia.

Beginning around the sixteenth century, groups of Vietnamese migrated to Cambodia and China for commerce and political purposes. Descendants of Vietnamese migrants in China form the Gin ethnic group in the country and primarily reside in and around Guangxi Province. Vietnamese form the largest ethnic minority group in Cambodia, at 5% of the population.[162] Under the Khmer Rouge, they were heavily persecuted and survivors of the regime largely fled to Vietnam.

During French colonialism, Vietnam was regarded as the most important colony in Asia by the French colonial powers, and the Vietnamese had a higher social standing than other ethnic groups in French Indochina.[163] As a result, educated Vietnamese were often trained to be placed in colonial government positions in the other Asian French colonies of Laos and Cambodia rather than locals of the respective colonies. There was also a significant representation of Vietnamese students in France during this period, primarily consisting of members of the elite class. A large number of Vietnamese also migrated to France as workers, especially during World War I and World War II, when France recruited soldiers and locals of its colonies to help with war efforts in Metropolitan France. The wave of migrants to France during World War I formed the first major presence of Vietnamese people in France and the Western world.[164]

When Vietnam gained its independence from France in 1954, a number of Vietnamese loyal to the colonial government also migrated to France. During the partition of Vietnam into North and South, a number of South Vietnamese students also arrived to study in France, along with individuals involved in commerce for trade with France, which was a principal economic partner with South Vietnam.[164]

Forced repatriation in 1970 and deaths during the Khmer Rouge era reduced the Vietnamese population in Cambodia from between 250,000 and 300,000 in 1969 to a reported 56,000 in 1984.[165]

The Fall of Saigon and end of the Vietnam War prompted the start of the Vietnamese diaspora, which saw millions of Vietnamese fleeing the country from the new communist regime. Recognizing an international humanitarian crisis, many countries accepted Vietnamese refugees, primarily the United States, France, Australia and Canada.[166] Meanwhile, under the new communist regime, tens of thousands of Vietnamese were sent to work or study in Eastern Bloc counties of Central and Eastern Europe as development aid to the Vietnamese government and for migrants to acquire skills that were to be brought home to help with development.[167] However, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, a vast majority of these overseas Vietnamese decided to remain in their host nations.[citation needed]

DNA and genetics analysis

This article needs attention from an expert in genetics. (January 2021) |

Anthropometry

Stephen Pheasant (1986), who taught anatomy, biomechanics and ergonomics at the Royal Free Hospital and the University College, London, said that East Asian and Southeast Asian people have proportionately shorter lower limbs than European people and black African people. Pheasant said that the proportionately short lower limbs of East Asian and Southeast Asian people is a difference that is most characterized in Japanese people, less characterized in Korean and Chinese people, and least characterized in Vietnamese and Thai people.[168][169]

Nguyen Manh Lien (1998) of the Vietnam Atomic Energy Commission indicated the average sitting height to body height ratios of Vietnamese 17-19 year olds to be 52.59% for males and 52.57% for females.[170]

Neville Moray (2005) indicated that modifications in basic cockpit geometry are required to accommodate Japanese and Vietnamese pilots. Moray said that the Japanese have longer torsos and a higher shoulder point than the Vietnamese, but the Japanese have about similar arm lengths to the Vietnamese, so the control stick would have to be moved 8 cm closer to the pilot for the Japanese and 7 cm closer to the pilot for the Vietnamese. Moray said that, due to having shorter legs than Americans (of European and African descent), rudder pedals must be moved closer to the pilot by 10 cm for the Japanese and 12 cm for the Vietnamese.[171]

Craniometry

Ann Kumar (1998) said that Michael Pietrusewsky (1992) said that, in a craniometric study, Borneo, Vietnam, Sulu, Java, and Sulawesi are closer to Japan, in that order, than Mongolian and Chinese populations are close to Japan. In the craniometric study, Michael Pietrusewsky (1992) said that, even though Japanese people cluster with Mongolians, Chinese and Southeast Asians in a larger Asian cluster, Japanese people are more closely aligned with several mainland and island Southeast Asian samples than with Mongolians and Chinese.[172][173]

Hirofumi Matsumura et al. (2001) and Hideo Matsumoto et al. (2009) said that the Japanese and Vietnamese people are regarded to be a mix of Northeast Asians and Southeast Asians who are related to today Austronesian peoples. But the amount of northern genetics is higher in Japanese people compared to Vietnamese who are closer to other Southeast Asians (Thai or Bamar people).[174][175]

Bradley J. Adams, a forensic anthropologist in the Office of Chief Medical Examiner of the City of New York, said that Vietnamese people could be classified as Mongoloid.[176][177]

A 2009 book about forensic anthropology said that Vietnamese skulls are more gracile and less sexually dimorphic than the skulls of Native Americans.[178]

Matsumura and Hudson (2005) said that a broad comparison of dental traits indicated that modern Vietnamese and other modern Southeast Asians derive from a northern source, supporting the immigration hypothesis, instead of regional continuity hypothesis, as the model for the origins of modern Southeast Asians.[179]

Genetics

Vietnamese show a close genetic relationship with other Southeast Asians.[180] The reference population for Vietnamese (Kinh) used in the Geno 2.0 Next Generation is 83% Southeast Asia & Oceania, 12% Eastern Asia and 3% Southern Asia.[181]

Jin Han-jun et al. (1999) said that the mtDNA 9‐bp deletion frequencies in the intergenic COII/tRNALys region for Vietnamese (23.2%) and Indonesians (25.0%), which are the two populations constituting Southeast Asians in the study, are relatively high frequencies when compared to the 9-bp deletion frequencies for Mongolians (5.1%), Chinese (14.2%), Japanese (14.3%) and Koreans (15.5%), which are the four populations constituting East Asians in the study. The study said that these 9-bp deletion frequencies are consistent with earlier surveys which showed that 9-bp deletion frequencies increase going from Japan to mainland Asia to the Malay Peninsula, which is supported by the following studies: Horai et al. (1987); Hertzberg et al. (1989); Stoneking & Wilson (1989); Horai (1991); Ballinger et al. (1992); Hanihara et al. (1992); and Chen et al. (1995). The Cavalli-Sforza's chord genetic distance (4D), from Cavalli-Sforza & Bodmer (1971), which is based on the allele frequencies of the intergenic COII/tRNALys region, between Vietnamese and other East Asian populations in the study, from least to greatest, are as follows: Vietnamese to Indonesian (0.0004), Vietnamese to Chinese (0.0135), Vietnamese to Japanese (0.0153), Vietnamese to Korean (0.0265) and Vietnamese to Mongolian (0.0750).[182]

Kim Wook et al. (2000) said that, genetically, Vietnamese people more probably clustered with East Asians of which the study analyzed DNA samples of Chinese, Japanese, Koreans and Mongolians rather than with Southeast Asians of which the study analyzed DNA samples of Indonesians, Filipinos, Thais and Vietnamese. The study said that Vietnamese people were the only population in the study's phylogenetic analysis that did not reflect a sizable genetic difference between East Asian and Southeast Asian populations. The study said that the likely reason for Vietnamese people more probably clustering with East Asians was genetic drift and distinct founder populations. The study said that the alternative reason for Vietnamese people more probably clustering with East Asians is a recent range expansion from South China. The study mentioned that the majority of its Vietnamese DNA samples were from Hanoi which is the closest region to South China.[183]

Schurr & Wallace (2002) said that Vietnamese people display genetic similarities with certain peoples from Malaysia. The study said that the aboriginal groups from Malaysia, the Orang Asli, are somewhat genetically intermediate between Malay people and Vietnamese. The study said that mtDNA haplogroup F is present at its highest frequency in Vietnamese and a high frequency of this haplogroup is also present in the Orang Asli, a people with whom Vietnamese have a linguistic connection (Austroasiatic languages).[184]

Jung Jongsun et al. (2010) said that genetic structure analysis found significant admixture in "Vietnamese (or Cambodian) with unknown Southern original settlers." The study said that it used Cambodians and Vietnamese to represent "Southern people," and the study used Cambodia (Khmer) and Vietnam (Kinh) as its populations for "South Asia." The study said that Chinese people are located between Korean and Vietnamese people in the study's genome map. The study also said that Vietnamese people are located between Chinese and Cambodian people in the study's genome map.[185]

He Jun-dong et al. (2012) did a principal component analysis using the NRY haplogroup distribution frequencies of 45 populations, and the second principal component showed a close affinity between Kinh and Vietnamese who were most likely Kinh with populations from mainland southern China because of the high frequency of NRY haplogroup O-M88. The study said that Kinh often have NRY haplogroup O-M7 which is the characteristic Chinese haplogroup. Out of the study's sample of seventy-six Kinh NRY haplogroups, twenty-three haplogroups (30.26%) were O-M88 and eight haplogroups (10.53%) were O-M7. The study said that, in ancient northern Vietnam, it is suggested that there has been considerable assimilation of inhabitants from present-day southern China through immigration into the Kinh people.[186]

A 2015 study revealed that Vietnamese (Kinh) test subjects showed more genetic variants in common with Chinese compared to Japanese.[187]

Sara Pischedda et al. (2017) stated that modern Vietnamese have a major component of their ethnic origin coming from the now-called southern China region and a minor component from a Thai-Indonesian composite. The study said that admixture analysis indicates that Vietnamese Kinh have a major part which is most common in Chinese and two minor parts which have the highest prevalence in the Bidayuh of Malaysia and the Proto-Malay. The study said that multidimensional scaling analysis indicates that Vietnamese Kinh have a closeness to Malay people, Thai and Chinese, and the study said that Malays and Thai are the samples which could be admixed with Chinese in the Vietnamese gene pool. The study said that Vietnamese mtDNA genetic variation matches well with the pattern seen in Southeast Asia, and the study said that most Vietnamese people had mtDNA haplotypes that clustered in clades M7 (20%) and R9’F (27%) which are clades that also dominate maternal lineages in Southeast Asia more generally.[188]

Genome sequencing by Vietnamese researchers

Vinh S. Le et al. (2019) elucidated that Kinh and present‐day Southeast Asian (SEA) populations mainly originated from SEA ancestries, while Southern Han Chinese (CHS) and Northern Han Chinese (CHB) populations were mixed from both Southeast Asian and East Asian ancestries. The results are generally compatible with that from the 1KG project (2015 Genomes Project Consortium et al., 2015) and the HUGO Pan‐Asian SNP Consortium (Abdulla et al., 2009). The results from both phylogenetic tree reconstruction and PCA also reinforce the hypothesis that a population migration from Africa to Asia following the South‐to‐North route (Abdulla et al., 2009; Chu et al., 1998). Interestingly, it was discovered that Kinh and Thai people "had similar genomic structures and close evolutionary relationships".[189]

Y-chromosome DNA

Kayser et al. (2006) found four members of O-M95, four members of O-M122(xM134), one member of C-M217, and one member of O-M119 in a sample of ten individuals from Vietnam.[190]

He Jun-dong et al. (2012) found that the NRY haplogroup profile for a sample of 76 Kinh in Hanoi, Vietnam was as follows: twenty-three (30.26%) belonged to O-M88, nine (11.84%) belonged to O-M95*(xM88), nine (11.84%) belonged to C-M217, eight (10.53%) belonged to O-M7, seven (9.21%) belonged to O-M134, seven (9.21%) belonged to O-P200*(xM121, M164, P201, 002611), five (6.58%) belonged to O-P203, two (2.63%) belonged to N-M231, two (2.63%) belonged to O-002611, two (2.63%) belonged to O-P201*(xM7, M134), one (1.32%) belonged to K-P131*(xN-M231, O-P191, Q-P36, R-M207), and one (1.32%) belonged to R-M17.[186]

Having analyzed the Y-DNA of another sample of 24 males from Hanoi, Vietnam, Trejaut et al. (2014) found that six (25.0%) belonged to O-M88, three (12.5%) belonged to O-M7, three (12.5%) belonged to O-M134(xM133), two (8.3%) belonged to O-M95(xM88), two (8.3%) belonged to C-M217, two (8.3%) belonged to N-LLY22g(xM128, M178), one (4.2%) belonged to O-PK4(xM95), one (4.2%) belonged to O-JST002611, one (4.2%) belonged to O-M133, one (4.2%) belonged to O-M159, one (4.2%) belonged to O-M119(xP203, M50), and one (4.2%) belonged to D-M15.[191]

A study published in 2010 reported the following data obtained through analysis of the Y-DNA of a sample from Vietnam (more precisely, Austro-Asiatic speakers from Southern Vietnam according to He Jun-dong et al.): 20.0% (14/70) O-M111, 15.7% (11/70) O-M134, 14.3% (10/70) O-JST002611, 7.1% (5/70) O-M95(xM111), 7.1% (5/70) Q-P36(xM346), 5.7% (4/70) O-M7, 5.7% (4/70) O-P203, 4.3% (3/70) C-M217, 2.9% (2/70) D-M15, 2.9% (2/70) N-LLY22g(xM178, M128), 2.9% (2/70) O-P197*(xJST002611, P201), 2.9% (2/70) O-47z, 1.4% (1/70) J2-M172, 1.4% (1/70) J-M304(xM172), 1.4% (1/70) O-P201(xM7, M134), 1.4% (1/70) O-P31(xM176, M95), 1.4% (1/70) O-M176(x47z), 1.4% (1/70) R-M17.[192]

The individuals who comprise the KHV (Kinh in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam) sample of the 1000 Genomes Project have been found to belong to the following Y-DNA haplogroups: 26.1% (12/46) O-M88/M111, 13.0% (6/46) O-M7, 8.7% (4/46) O-JST002611, 8.7% (4/46) O-F444 (= O-M134(xM117)), 8.7% (4/46) O-M133, 6.5% (3/46) O-M95(xM88/M111), 4.3% (2/46) O-P203.1, 4.3% (2/46) O-F2159 (= O-KL2(xJST002611)), 4.3% (2/46) Q-Y529, 2.2% (1/46) O-CTS9996 (= O-K18(xM95)), 2.2% (1/46) O-CTS1754 (= O-M122(xM324)), 2.2% (1/46) O-F4124 (= O-N6 or O-P164(xM134)), 2.2% (1/46) C-F845, 2.2% (1/46) F-Y27277(xM427, M428), 2.2% (1/46) N1b2a-M1811, 2.2% (1/46) N1a2a-M128.[193][194]

Macholdt et al. (2020) tested a sample of Kinh (n=50, including 42 from Hanoi, three from Nam Trực District, two from Yên Phong District, one from Ngô Quyền District, one from Bắc Hà District, and one from Nghĩa Hưng District) and found that they belonged to the following Y-DNA haplogroups: 44% haplogroup O1b1a1a-M95, 30% haplogroup O2a-M324, 10% haplogroup C2c1-F2613, 4% haplogroup O1a1a-M307.1, 4% haplogroup N1-M2291, 4% haplogroup Q1a1a1-M120, 2% haplogroup O1b1a2a1-F1759, and 2% haplogroup H1a2a-Z4487.[195]

Mitochondrial DNA

Schurr & Wallace (2002) displayed the mtDNA haplogroup profile for a sample of 28 Vietnamese as follows: 17.9% belonged to B/B*, 32.1% belonged to F, 32.1% belonged to M and 17.9% belonged to other haplogroups.[184]

He Jun-dong et al. (2012) found that the mtDNA haplogroup profile for a sample of 139 Kinh was as follows: twenty-four (17.27%) belonged to B4, nineteen (13.67%) belonged to B5, one (0.72%) belonged to B6, four (2.88%) belonged to D, twenty-nine (20.86%) belonged to F, one (0.72%) belonged to G, seven (5.04%) belonged to M*, twenty-one (15.11%) belonged to M7, twelve (8.63%) belonged to M8, four (2.88%) belonged to M9a'b, one (0.72%) belonged to M10, two (1.44%) belonged to M12, one (0.72%) belonged to N*, two (1.44%) belonged to N9a, ten (7.19%) belonged to R9 and one (0.72%) belonged to W4.[186]

Sara Pischedda et al. (2017) found that the mtDNA haplogroup profile for a sample of 399 Kinh was as follows: 1% belonged to A, 23% belonged to B, 2% belonged to C, 4% belonged to D, 35% belonged to M (xD,C), 8% belonged to N(xB,R9'F,A) and 27% belonged to R9'F.[188]

Genetic contribution to Koreans

Bhak Jong-hwa, a professor in the biomedical engineering department at the Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology (UNIST), said that the ancient Vietnamese, which was a population that flourished with rapid agricultural development after 8,000 BC, slowly travelled north to ancient civilizations in the Korean Peninsula and the Russian Far East. Bhak said that Korean people were formed from the admixture of agricultural Southern Mongoloids from Vietnam who went through China, hunter-gatherer Northern Mongoloids in the Korean Peninsula and another group of Southern Mongoloids. Bhak said, "We believe the number of ancient dwellers who migrated north from Vietnam far exceeds the number of those occupying the peninsula," making Koreans inherit more of their DNA from southerners.[196][197]

In later history, there was intermarriage between the aristocracies of Korea and Vietnam, especially with that involving an heir of the Lý Dynasty, Lý Long Tường, who was exiled to Goryeo and who was to become the progenitor of the Hwasan Lee clan that would take root on the Korean peninsula.

See also

- Baiyue

- Lạc Việt

- Âu Lạc

- Vietnamese language

- List of Vietnamese people

- Overseas Vietnamese (Known as "Việt Kiều")

- Vietnamese culture

- Vietnamese cuisine

- Vietnamese music

- Vietnamese name

- List of ethnic groups in Vietnam

- History of Vietnam

- Southeast Asia

- Ethnic groups of Southeast Asia

- Vietnamese clothing

Notes

- ^ Neither the American government nor Ngô Đình Diệm's State of Vietnam signed anything at the 1954 Geneva Conference. The non-communist Vietnamese delegation objected strenuously to any division of Vietnam; however, the French accepted the Việt Minh proposal[134] that Vietnam be united by elections under the supervision of "local commissions".[135] The United States, with the support of South Vietnam and the United Kingdom, countered with the "American Plan",[136] which provided for United Nations-supervised unification elections. The plan, however, was rejected by Soviet and other communist delegations.[137]

- ^ The number of Vietnamese citizens currently in Taiwan was 243,734 as of 31 July 2021 (145,271 males, 98,463 females) while the number of Vietnamese citizens holding a valid residence permit was 268,230 (157,914 males, 110,316 females)

- ^ Excluding Gin people, who are usually classified as a separate but closely related ethnic group.

References

- ^ Jump up to: a b c General Statistics Office of Vietnam (2019). "Completed Results of the 2019 Viet Nam Population and Housing Census" (PDF). Statistical Publishing House (Vietnam). ISBN 978-604-75-1532-5.

- ^ "Asian and Pacific Islander Population in the United States census.gov". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on March 21, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ Ponnudurai, Parameswaran (19 March 2014). "Ethnic Vietnamese in Cambodia Left in Limbo Without Citizenship". Radio Free Asia. RFA Khmer Service. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ "Vietnamese in Cambodia". Joshua Project. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ "A People in Limbo, Many Living Entirely on the Water". The New York Times. 2018-03-28.

- ^ "Vietnam pips South Korea, becomes second largest foreigners group in Japan". VnExpress. 2021-04-03.

- ^ "Les célébrations du Têt en France par la communauté vietnamienne" (in French). Le Petit Journal. Retrieved 2020-09-28.

- ^ Étude de la Transmission Familiale et de la Practique du Parler Franco-Vietnamien (in French) Retrieved on 22-12-2015.

- ^ "2016 Census Community Profiles". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ^ 統計資料. National Immigration Agency, Ministry of the Interior, Republic of China (Taiwan). 2021-07-31.

- ^ "Census Profile, 2016 Census". Statistics Canada. 7 February 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ "Vietnam ranks second in number of foreigners staying in RoK". Vietnam Times. February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Bevölkerung in Privathaushalten 2019 nach Migrationshintergrund". Federal Statistical Office of Germany (Statistisches Bundesamt). 28 July 2020.

- ^ "Национальный сос��ав населения по субъектам Российской Федерации". Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ^ L. Anh Hoang; Cheryll Alipio (2019). Money and Moralities in Contemporary Asia. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 59–84. ISBN 9789048543151.

- ^ "Vietnamese in Laos". joshuaproject.net.

- ^ "Chủ tịch Quốc hội gặp gỡ cộng đồng người Việt Nam tại Thái Lan" (in Vietnamese). Retrieved 2021-02-02.

- ^ "Người Việt bán hàng rong ở Thái Lan". Radio Free Asia.

- ^ Foreigners, total by citizenship as at 31 December 2018 1). Czech Statistical Office

- ^ "Die Vietnamesen, eine aktive Minderheit in Tschechien". Arte. 2 June 2009. Archived from the original on 12 December 2012.

- ^ "Viet Nam, Malaysia's trade unions ink agreement to strengthen protection of migrant workers". International Labour Organization. 16 March 2015.

- ^ (in Polish) SPOŁECZNOŚĆ WIETNAMSKA W POLSCE POLITYKA MIGRACYJNA WIETNAMU, Wydział Analiz Migracyjnych, Departament Polityki Migracyjnej Ministerstwo Spraw Wewnętrznych i Administracji, Warszawa, czerwiec 2007. P.34

- ^ "Wietnamczycy upodobali sobie Polskę. Może być ich 60 tys. w naszym kraju". www.wiadomosci24.pl (in Polish). 4 September 2012. Retrieved 2015-11-02.

- ^ "Vietnam who after 30 years in the UK". Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- ^ "Cuộc sống người Việt ở Angola". RFA. 1 June 2013.

- ^ "Protecting Vietnamese community in Ukraine". Vietnamese Embassy in Ukraine. Retrieved 2021-02-02.

- ^ "Vietnamese come to Ukraine for a better life, although many long to return to homeland". Kyiv Post. December 3, 2009.

- ^ "Major Figures on Residents from Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan and Foreigners Covered by 2010 Population Census". National Bureau of Statistics of China. April 29, 2011. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- ^ "Immigrants and Norwegian-born to immigrant parents". Retrieved 2021-02-02.

- ^ "Population; sex, age, migration background and generation, 1 January". Statistics Netherlands. Retrieved 2021-02-02.

- ^ "Population by country of birth and year". Retrieved 2021-02-02.

- ^ "Việt Nam opens consulate office in China's Macau". Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ "Embassy of the UAE in Hanoi » Vietnam - UAE Relations-Bilateral relations between UAE - Vietnam". Archived from the original on 2014-01-10. Retrieved 2014-02-25.

- ^ "CỘNG ĐỒNG NGƯỜI VIỆT NAM Ở Ả-RẬP XÊ-ÚT MỪNG XUÂN ẤT MÙI - 2015". Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- ^ "Người trong cuộc kể lại cuộc sống "như nô lệ" của lao động Việt ở Ả Rập Saudi". 3 January 2020. Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- ^ "Tình cảnh 'Ô-sin' Việt ở Saudi: bị bóc lột, bỏ đói". Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- ^ "FOLK1C: Population at the first day of the quarter by region, sex, age (5 years age groups), ancestry and country of origin". Statistics Denmark.

- ^ [1]. Chimviet.free.fr(in French). Retrieved on 2019-11-19.

- ^ "Người Việt ở Bỉ và Đảng cộng sản kiểu mới, trẻ và hiện đại". BBC. 22 May 2019.

- ^ "Population 31.12. by Area, Background country, Sex, Year and Information". Tilastokeskuksen PX-Web tietokannat.

- ^ "Cộng đồng người Việt Nam tại Singapore đón xuân Nhâm Thìn".

- ^ "Vietnamese in Cyprus, Laos celebrate traditional New Year". Vietnamplus. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ Deputy FM meets Vietnamese nationals in Cyprus. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- ^ https://www.minv.sk/swift_data/source/policia/hranicna_a_cudzinecka_policia/rocenky/rok_2019/2019-rocenka-UHCP_EN.pdf

- ^ a.s, Petit Press (July 28, 2015). "Slovakia's 'invisible minority' counters migration fears". spectator.sme.sk.

- ^ "2018 Census ethnic groups dataset | Stats NZ". www.stats.govt.nz.

- ^ "Vietnamese community in Switzerland support fight against coronavirus". vietnamnews.vn.

- ^ Vukovich, Gabriella (2018). Mikrocenzus 2016 - 12. Nemzetiségi adatok [2016 microcensus - 12. Ethnic data] (PDF). Hungarian Central Statistical Office (in Hungarian). Budapest. ISBN 978-963-235-542-9. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ "Người Việt tại tâm dịch của Italia" (in Vietnamese). VOV. 2020-03-27.

- ^ "Truyền "ngọn lửa" văn hóa cho thế hệ trẻ người Việt tại Áo" (in Vietnamese). 2020-02-23.

- ^ "Condiții inumane pentru muncitorii vietnamezi din România". Digi24 (in Romanian). 21 March 2019.

- ^ "Lấy quốc tịch Châu Âu thông qua con đường Bulgaria" (in Vietnamese). Tuổi Trẻ. 2019-03-13.

- ^ Pew Research Center: The Global Religious Landscape 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Norman, Jerry; Mei, Tsu-lin (1976). "The Austroasiatics in Ancient South China: Some Lexical Evidence". Monumenta Serica. 32: 274–301. doi:10.1080/02549948.1976.11731121.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Meacham, William (1996). "Defining the Hundred Yue". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 15: 93–100. doi:10.7152/bippa.v15i0.11537. Archived from the original on 2014-02-28.

- ^ The Annals of Lü Buwei, translated by John Knoblock and Jeffrey Riegel, Stanford University Press (2000), p. 510. ISBN 978-0-8047-3354-0. "For the most part, there are no rulers to the south of the Yang and Han Rivers, in the confederation of the Hundred Yue tribes."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lieberman 2003, p. 405.

- ^ Taylor 2013, pp. 4–6.

- ^ Blench, Roger. 2018. Waterworld: lexical evidence for aquatic subsistence strategies in Austroasiatic. In Papers from the Seventh International Conference on Austroasiatic Linguistics, 174-193. Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society Special Publication No. 3. University of Hawaiʻi Press.

- ^ Blench, Roger. 2017. Waterworld: lexical evidence for aquatic subsistence strategies in Austroasiatic. Presented at ICAAL 7, Kiel, Germany.

- ^ Sidwell, Paul. 2015b. Phylogeny, innovations, and correlations in the prehistory of Austroasiatic. Paper presented at the workshop Integrating inferences about our past: new findings and current issues in the peopling of the Pacific and South East Asia, 22–23 June 2015, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, Jena, Germany.

- ^ Reconstructing Austroasiatic prehistory. In P. Sidwell & M. Jenny (Eds.), The Handbook of Austroasiatic Languages. Leiden: Brill. (Page 1: “Sagart (2011) and Bellwood (2013) favour the middle Yangzi”

- ^ Peiros, Ilia (2011). "Some thoughts on the problem of the Austro-Asiatic homeland" (PDF). Journal of Language Relationship. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ^ Chamberlain 2000, p. 40.

- ^ Schliesinger (2018a), pp. 21, 97.

- ^ Schliesinger (2018b), pp. 3–4, 22, 50, 54.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Churchman (2010), p. 36.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, p. 52.

- ^ Kelley 2016, pp. 165–167.

- ^ Kelley 2016, p. 175.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schafer 1967, p. 14.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kiernan 2019, p. 53.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, p. 56.

- ^ Kelley 2016, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, p. 69.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, p. 75.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, p. 73.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, pp. 75–77.

- ^ Schafer 1967, p. 81.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, p. 81.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, p. 84.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, p. 92.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, p. 91.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Maspero 1912, p. 10.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, p. 43.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, p. 109.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, p. 110.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, p. 111.

- ^ Schafer 1967, p. 63.

- ^ Taylor 1983, p. 248.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, p. 127.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, p. 139.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, p. 141.

- ^ Lieberman 2003, p. 352.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Bellwood & Glover 2004, p. 229.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, p. 157.

- ^ Marsh 2016, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, p. 148.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, pp. 153–154.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, p. 155.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, pp. 135, 138.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, pp. 169, 170.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, pp. 194–197.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, p. 212.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, pp. 204–211.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, pp. 221–223.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Kiernan 2019, pp. 233–234.

- ^ Lieberman 2003, p. 433.

- ^ McLeod 1991, p. 61.

- ^ Ooi 2004, p. 520.

- ^ Cook 2001, p. 396.

- ^ Frankum Jr. 2011, p. 172.

- ^ Nhu Nguyen 2016, p. 37.

- ^ Lim 2014, p. 33.

- ^ Largo 2002, p. 112.

- ^ Khánh Huỳnh 1986, p. 98.

- ^ Odell & Castillo 2008, p. 82.

- ^ Thomas 2012.

- ^ Miller 1990, p. 293.

- ^ Gettleman et al. 1995, p. 4.

- ^ Thanh Niên 2015.

- ^ Vietnam Net 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Joes 1992, p. 95.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Pike 2011, p. 192.

- ^ Gunn 2014, p. 270.

- ^ Neville 2007, p. 124.

- ^ Tonnesson 2011, p. 66.

- ^ Waite 2012, p. 89.

- ^ Gravel 1971, p. 134.

- ^ Gravel 1971, p. 119.

- ^ Gravel 1971, p. 140.

- ^ Kort 2017, p. 96.

- ^ Olson 2012, p. 43.

- ^ DK 2017, p. 39.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c van Dijk et al. 2013, p. 68.

- ^ Guttman, John (25 July 2013). "Why did Sweden support the Viet Cong?". History Net. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- ^ The New York Times 1976.

- ^ Hirschman, Preston & Manh Loi 1995.

- ^ Shenon 1995.

- ^ Obermeyer, Murray & Gakidou 2008.

- ^ Elliott 2010, pp. 499, 512–513.

- ^ Sagan & Denny 1982.

- ^ Spokesman-Review 1977, p. 8.

- ^ Kissi 2006, p. 144.

- ^ Meggle 2004, p. 166.

- ^ Hampson 1996, p. 175.

- ^ Jump up to: a b BBC News 1997.

- ^ Văn Phúc 2014.

- ^ Murray 1997, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bich Loan 2007.

- ^ Howe 2016, p. 20.

- ^ Goodkind 1995.

- ^ Gallup 2002.

- ^ Wagstaff, van Doorslaer & Watanabe 2003.

- ^ [2]

- ^ Pew Research Center: [3].

- ^ CIA – The World Factbook, Cambodia, retrieved 11 December 2012

- ^ Carine Hahn, Le Laos, Karthala, 1999, page 77

- ^ Jump up to: a b La Diaspora Vietnamienne en France un cas particulier Archived 2013-12-03 at the Wayback Machine (in French)

- ^ "Cambodia – Population". Library of Congress Country Studies.

- ^ "Online Exhibitions - Exhibitions - Canadian Museum of History". www.civilization.ca.

- ^ Hillmann 2005, p. 87

- ^ Pheasant, Stephen. (2003). Bodyspace: Anthropometry, ergonomics and the design of work (2nd. ed.). Taylor & Francis. Page 159. Retrieved March 14, 2018, from Google Books.

- ^ Buckle, Peter. (1996). Obituary. Work & Stress, 10(3). Page 282. Retrieved March 14, 2018, from link to the PDF document.

- ^ Nguyen, M.L. (1998). Compilation of Anatomical, Physiological and Metabolic Characteristics for a Reference Vietnamese Man. Compilation of anatomical, physiological and metabolic characteristics for a Reference Asian Man Volume 2: Country reports. Austria: International Atomic Energy Committee. Page 168. Wayback Machine link.

- ^ Moray, Neville. (2005). Ergonomics: The history and scope of human factors. London and New York: Taylor & Francis. Page 327. ISBN: 0-415-32258-8 Google Books link.

- ^ Kumar, Ann. (1998). An Indonesian Component in the Yayoi?: the Evidence of Biological Anthropology. Anthropological Science 106(3). Page 268. Retrieved February 22, 2018, from link to the PDF document.

- ^ Pietrusewsky, Michael. (1992). Japan, Asia and the Pacific: A multivariate craniometric investigation. In book: Japanese as a member of the Asian and Pacific populations, Publisher: Kyoto: International Research Center for Japanese Studies. International Symposium No. 4., Page 47. Retrieved February 22, 2018, from link to the article.

- ^ Matsumura, Hirofumi et al. (2001). Dental Morphology of the Early Hoabinian, the Neolithic Da But and the Metal Age Dong Son Civilized Peoples in Vietnam. Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie 83(1). Retrieved March 1, 2018, from link to the article's abstract.

- ^ MATSUMOTO, Hideo (2009). "The origin of the Japanese race based on genetic markers of immunoglobulin G". Proceedings of the Japan Academy, Series B. 85 (2): 69–82. Bibcode:2009PJAB...85...69M. doi:10.2183/pjab.85.69. ISSN 0386-2208. PMC 3524296. PMID 19212099.

- ^ Forensic Anthropology. (2017). Infobase Publishing. Retrieved June 12, 2017, from link.

- ^ Adams, Bradley J. (2007). Forensic Anthropology. USA: Chelsea House. Page 44. ISBN 978-0-7910-9198-2 Retrieved June 12, 2017, from link.

- ^ Steadman, Dawnie Wolfe. (2009). Hard Evidence: Case Studies in Forensic Anthropology. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis. Page 403. Retrieved January 7, 2018, from link.

- ^ Matsumura, Hirofumi et al. (2011). In book: Dynamics of Human Diversity: The Case of Mainland Southeast Asia, Chapter: Population history of mainland Southeast Asia: the Two Layer model in the context of Northern Vietnam, Publisher: Canberra: Pacific Linguistics, Editors: Enfield NJ, White JC. Pages 154, 155, 156, 158 & 169. Retrieved February 24, 2018, from link to the article.

- ^ Yuliwulandari, R.; Kashiwase, K.; Nakajima, H.; Uddin, J.; Susmiarsih, T. P.; Sofro, A. S. M.; Tokunaga, K. (January 2009). "Polymorphisms of HLA genes in Western Javanese (Indonesia): close affinities to Southeast Asian populations". Tissue Antigens. 73 (1): 46–53. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0039.2008.01178.x. PMID 19140832.

- ^ "Reference Populations – Geno 2.0 Next Generation". National Geographic. Retrieved May 14, 2017.

- ^ Jin, Han-jun et al. (1999). Distribution of length variation of the mtDNA 9‐bp motif in the intergenic COII/tRNALys region in East Asian populations. Korean Journal of Biological Sciences 3(4). Pages 395 & 396. Retrieved March 2, 2018, from link to the article's abstract.

- ^ Kim, Wook et al. (2000). Y chromosomal DNA variation in East Asian populations and its potential for inferring the peopling of Korea. Journal of Human Genetics 45(2). Pages 77, 80 & 82. doi:10.1007/s100380050015 PMID 10721667 Retrieved February 19, 2018, from link.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schurr, Theodore G. & Wallace, Douglas C. (2002). Mitochondrial DNA Diversity in Southeast Asian Populations. Human Biology, 74(3). Pages 433, 439, 446, 447 & 448. Retrieved January 7, 2018, from link.

- ^ Jung, Jongsun et al. (2010). Gene Flow between the Korean Peninsula and Its Neighboring Countries. In PLOS ONE 5 (7). Pages 2, 4, 5 & 6. Retrieved February 25, 2018, from link.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c He, Jun-dong et al. (2012). Patrilineal Perspective on the Austronesian Diffusion in Mainland Southeast Asia. In PLoS 7(5), Page 7. Retrieved December 14, 2017, from link. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036437 PMID 22586471

- ^ Mission accomplished: Researchers successfully sequence Vietnamese human genome. (2015). Thanh Niên News. Retrieved May 14, 2017, from link.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pischedda, S. et al. (2017). Phylogeographic and genome-wide investigations of Vietnam ethnic groups reveal signatures of complex historical demographic movements. Scientific Reports, 7(1). Pages 4, 6, 11, 13, & 14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12813-6 Retrieved January 6, 2018, from link.

- ^ Le, Vinh S; Tran, Kien T.; Bui, Hoa T. P.; Le, Huong T. T.; Nguyen, Canh D.; Do, Duong H.; Ly, Ha T. T.; Pham, Linh T. D.; Dao, Lan T. M.; Nguyen, Liem T. (10 June 2019). "A Vietnamese human genetic variation database". Human Mutation. 40 (10): 1664–1675. doi:10.1002/humu.23835. PMID 31180159. S2CID 182949236.

- ^ Kayser, Manfred; Brauer, Silke; Cordaux, Richard; Casto, Amanda; Lao, Oscar; Zhivotovsky, Lev A.; Moyse-Faurie, Claire; Rutledge, Robb B.; Schiefenhoevel, Wulf; Gil, David; Lin, Alice A.; Underhill, Peter A.; Oefner, Peter J.; Trent, Ronald J.; Stoneking, Mark (2006). "Melanesian and Asian Origins of Polynesians: mtDNA and Y Chromosome Gradients Across the Pacific". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 23 (11): 2234–2244. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl093. PMID 16923821.

- ^ Trejaut, Jean A; Poloni, Estella S; Yen, Ju-Chen; Lai, Ying-Hui; Loo, Jun-Hun; Lee, Chien-Liang; He, Chun-Lin; Lin, Marie (2014). "Taiwan Y-chromosomal DNA variation and its relationship with Island Southeast Asia". BMC Genetics. 2014 (15): 77. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-15-77. PMC 4083334. PMID 24965575.

- ^ Karafet, Tatiana M.; Hallmark, Brian; Cox, Murray P.; Sudoyo, Herawati; Downey, Sean; Lansing, J. Stephen; Hammer, Michael F. (2010). "Major East–West Division Underlies Y Chromosome Stratification across Indonesia". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 27 (8): 1833–1844. doi:10.1093/molbev/msq063. PMID 20207712.

- ^ "YTree". www.yfull.com.

- ^ Poznik, G. David; Xue, Yali; Mendez, Fernando L.; et al. (June 2016). "Punctuated bursts in human male demography inferred from 1,244 worldwide Y-chromosome sequences". Nature Genetics. 48 (6): 593–599. doi:10.1038/ng.3559. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-002A-F024-C. PMC 4884158. PMID 27111036.

- ^ Enrico Macholdt, Leonardo Arias, Nguyen Thuy Duong, et al., "The paternal and maternal genetic history of Vietnamese populations." European Journal of Human Genetics (2020) 28:636–645. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0557-4

- ^ Choi, Eun-kyung. (2017). Pinning down Korean-ness through DNA. Korea JoongAng Daily. Retrieved February 22, 2018, from link to the article.

- ^ Jang, Lina. (2017). Genome Research Finds Roots of Korean Ancestry in Vietnam. The Korea Bizwire. Retrieved February 22, 2018, from link to the article.

Bibliography

Books

- Akazawa, Takeru; Aoki, Kenichi; Kimura, Tasuku (1992). The evolution and dispersal of modern humans in Asia. Hokusen-sha. ISBN 978-4-938424-41-1.

- Anderson, David (2005). The Vietnam War (Twentieth Century Wars). Palgrave. ISBN 978-0333963371.

- Alterman, Eric (2005). When Presidents Lie: A History of Official Deception and Its Consequences. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-303604-3.

- Anderson, James A.; Whitmore, John K. (2014). China's Encounters on the South and Southwest: Reforging the Fiery Frontier Over Two Millennia. Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-28248-3.

- Bellwood, Peter; Glover, Ian, eds. (2004). Southeast Asia: From Prehistory to History. Routledge. ISBN 9780415297776.

- Brigham, Robert Kendall (1998). Guerrilla Diplomacy: The NLF's Foreign Relations and the Viet Nam War. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3317-7.

- Brindley, Erica (2015). Ancient China and the Yue: Perceptions and Identities on the Southern Frontier, C.400 BCE-50 CE. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107084780.

- Buttinger, Joseph (1958). The Smaller Dragon: A Political History of Vietnam. Praeger Publishers.

- Buttinger, Joseph (1968). Vietnam: A Political History. Praeger.

- Chua, Amy (2003). World On Fire. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. ISBN 978-0385721868.

- Chua, Amy (2018). Political Tribes: Group Instinct and the Fate of Nations. Penguin Press. ISBN 978-0399562853.

- Cima, Ronald J. (1987). Vietnam: A Country Study. United States Library of Congress. ISBN 978-0160181436.

- Cook, Bernard A. (2001). Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-8153-4057-7.

- Cortada, James W. (1994). Spain in the Nineteenth-century World: Essays on Spanish Diplomacy, 1789–1898. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-27655-2.

- Cottrell, Robert C. (2009). Vietnam. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-2147-5.

- Đào Duy Anh (2016) [First published 1964]. Đất nước Việt Nam qua các đời: nghiên cứu địa lý học lịch sử Việt Nam (in Vietnamese). Nha Nam. ISBN 978-604-94-8700-2.

- Dennell, Robin; Porr, Martin (2014). Southern Asia, Australia, and the Search for Human Origins. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-72913-1.

- van Dijk, Ruud; Gray, William Glenn; Savranskaya, Svetlana; Suri, Jeremi; et al. (2013). Encyclopedia of the Cold War. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-92311-2.

- DK (2017). The Vietnam War: The Definitive Illustrated History. Dorling Kindersley Limited. ISBN 978-0-241-30868-4.

- Dohrenwend, Bruce P.; Turse, Nick; Wall, Melanie M.; Yager, Thomas J. (2018). Surviving Vietnam: Psychological Consequences of the War for US Veterans. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-090444-9.

- Duy Hinh, Nguyen; Dinh Tho, Tran (2015). The South Vietnamese Society. Normanby Press. ISBN 978-1-78625-513-6.

- Eggleston, Michael A. (2014). Exiting Vietnam: The Era of Vietnamization and American Withdrawal Revealed in First-Person Accounts. McFarland Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7864-7772-2.

- Elliott, Mai (2010). RAND in Southeast Asia: A History of the Vietnam War Era. RAND Corporation. ISBN 978-0-8330-4915-5.

- Fitzgerald, C. P (1972). The Southern Expansion of the Chinese People. Barrie & Jenkins.

- Frankum Jr., Ronald B. (2011). Historical Dictionary of the War in Vietnam. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7956-0.

- Gettleman, Marvin E.; Franklin, Jane; Young, Marilyn B.; Franklin, H. Bruce (1995). Vietnam and America: A Documented History. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-3362-5.

- Gibbons, William Conrad (2014). The U.S. Government and the Vietnam War: Executive and Legislative Roles and Relationships, Part III: 1965–1966. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-6153-8.

- Gilbert, Adrian (2013). Encyclopedia of Warfare: From the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-135-95697-4.

- Gravel, Mike (1971). The Pentagon Papers: The Defense Department History of United States Decision-making on Vietnam. Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-0526-2.

- Gunn, Geoffrey C. (2014). Rice Wars in Colonial Vietnam: The Great Famine and the Viet Minh Road to Power. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4422-2303-5.

- Hampson, Fen Osler (1996). Nurturing Peace: Why Peace Settlements Succeed Or Fail. US Institute of Peace Press. ISBN 978-1-878379-55-9.

- Heneghan, George Martin (1969). Nationalism, Communism and the National Liberation Front of Vietnam: Dilemma for American Foreign Policy. Department of Political Science, Stanford University.

- Hiẻ̂n Lê, Năng (2003). Three victories on the Bach Dang river. Nhà xuất bản Văn hóa-thông tin.

- Hoàng, Anh Tuấn (2007). Silk for Silver: Dutch-Vietnamese Relations, 1637–1700. Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-15601-2.

- Holmgren, Jennifer (1980). Chinese Colonization of Northern Vietnam: Administrative Geography and Political Development in the Tonking Delta, First To Sixth Centuries A.D. Australian National University Press.

- Hong Lien, Vu; Sharrock, Peter (2014). Descending Dragon, Rising Tiger: A History of Vietnam. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78023-388-8.

- Howe, Brendan M. (2016). Post-Conflict Development in East Asia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-07740-4.

- Hyunh, Kim Khanh (1986). Vietnamese Communism, 1925-1945. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801493973.

- Isserman, Maurice; Bowman, John Stewart (2009). Vietnam War. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-0015-9.

- Jamieson, Neil L (1995). Understanding Vietnam. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520201576.

- Joes, Anthony James (1992). Modern Guerrilla Insurgency. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-275-94263-2.

- Jukes, Geoffrey (1973). The Soviet Union in Asia. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-02393-2.

- Karlström, Anna; Källén, Anna (2002). Southeast Asian Archaeology. Östasiatiska Samlingarna (Stockholm, Sweden), European Association of Southeast Asian Archaeologists. International Conference. Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities, Stockholm. ISBN 978-91-970616-0-5.

- Keith, Charles (2012). Catholic Vietnam: A Church from Empire to Nation. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-95382-6.

- Kelley, Liam C. (2014). "Constructing Local Narratives: Spirits, Dreams, and Prophecies in the Medieval Red River Delta". In Anderson, James A.; Whitmore, John K. (eds.). China's Encounters on the South and Southwest: Reforging the Fiery Frontier Over Two Millennia. United States: Brills. pp. 78–106. ISBN 978-9-004-28248-3.

- Kelley, Liam C. (2016), "Inventing Traditions in Fifteenth-century Vietnam", in Mair, Victor H.; Kelley, Liam C. (eds.), Imperial China and its southern neighbours, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, pp. 161–193, ISBN 978-9-81462-055-0

- Keyes, Charles F. (1995). The Golden Peninsula: Culture and Adaptation in Mainland Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1696-4.

- Khánh Huỳnh, Kim (1986). Vietnamese Communism, 1925–1945. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-9397-3.

- Khoo, Nicholas (2011). Collateral Damage: Sino-Soviet Rivalry and the Termination of the Sino-Vietnamese Alliance. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-15078-1.

- Kiernan, Ben (2017). Việt Nam: A History from Earliest Times to the Present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516076-5.

- Kiernan, Ben (2019). Việt Nam: a history from earliest time to the present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190053796.

- Kissi, Edward (2006). Revolution and Genocide in Ethiopia and Cambodia. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-1263-2.

- Kleeman, Terry F. (1998). Ta Chʻeng, Great Perfection – Religion and Ethnicity in a Chinese Millennial Kingdom. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1800-8.

- Kort, Michael (2017). The Vietnam War Re-Examined. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-04640-5.

- Largo, V. (2002). Vietnam: Current Issues and Historical Background. Nova Science. ISBN 978-1590333686.

- Leonard, Jane Kate (1984). Wei Yuan and China's Rediscovery of the Maritime World. Harvard Univ Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-94855-6.

- Lewy, Guenter (1980). America in Vietnam. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-991352-7.

- Li, Tana (1998). Cornell University. Southeast Asia Program (ed.). Nguyễn Cochinchina: Southern Vietnam in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Volume 23 of Studies on Southeast Asia (illustrated ed.). SEAP Publications. ISBN 0877277222. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

|volume=has extra text (help) - Li, Xiaobing (2012). China at War: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-415-3.

- Lieberman, Victor (2003). Strange Parallels: Integration of the Mainland Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800-1830, Vol 1. Cambridge University Press.

- Lim, David (2014). Economic Growth and Employment in Vietnam. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-81859-5.

- Lockard, Craig A. (2010). Societies, Networks, and Transitions, Volume 2: Since 1450. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-4390-8536-3.

- Marsh, Sean (2016), "CLOTHES MAKE THE MAN: Body Culture and Ethnic Boundaries on the Lingnan Frontier in the Southern Song", in Mair, Victor H.; Kelley, Liam C. (eds.), Imperial China and its southern neighbours, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, pp. 80–110

- McLeod, Mark W. (1991). The Vietnamese Response to French Intervention, 1862–1874. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-93562-7.

- Meggle, Georg (2004). Ethics of Humanitarian Interventions. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-032773-1.

- Miksic, John Norman; Yian, Go Geok (2016). Ancient Southeast Asia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-27903-7.

- Miller, Robert Hopkins (1990). United States and Vietnam 1787–1941. DIANE Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7881-0810-5.

- Moïse, Edwin E. (2017). Land Reform in China and North Vietnam: Consolidating the Revolution at the Village Level. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-7445-5.

- Muehlenbeck, Philip Emil; Muehlenbeck, Philip (2012). Religion and the Cold War: A Global Perspective. Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 978-0-8265-1852-1.

- Murphey, Rhoads (1997). East Asia: A New History. Pearson. ISBN 978-0205695225.

- Murray, Geoffrey (1997). Vietnam Dawn of a New Market. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-17392-0.

- Neville, Peter (2007). Britain in Vietnam: Prelude to Disaster, 1945–46. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-24476-8.

- Olsen, Mari (2007). Soviet-Vietnam Relations and the Role of China 1949–64: Changing Alliances. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-17413-3.

- Olson, Gregory A. (2012). Mansfield and Vietnam: A Study in Rhetorical Adaptation. MSU Press. ISBN 978-0-87013-941-3.

- Ooi, Keat Gin (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-770-2.

- Ooi, Keat Gin; Anh Tuan, Hoang (2015). Early Modern Southeast Asia, 1350–1800. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-55919-1.

- Oxenham, Marc; Buckley, Hallie (2015). The Routledge Handbook of Bioarchaeology in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-53401-3.

- Oxenham, Marc; Tayles, Nancy (2006). Bioarchaeology of Southeast Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82580-1.

- Page, Melvin Eugene; Sonnenburg, Penny M. (2003). Colonialism: An International, Social, Cultural, and Political Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-335-3.

- Phan, Huy Lê; Nguyễn, Quang Ngọc; Nguyễn, Đình Lễ (1997). The Country Life in the Red River Delta.

- Phuong Linh, Huynh Thi (2016). State-Society Interaction in Vietnam. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3-643-90719-6.

- Pike, Francis (2011). Empires at War: A Short History of Modern Asia Since World War II. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0-85773-029-9.

- Rabett, Ryan J. (2012). Human Adaptation in the Asian Palaeolithic: Hominin Dispersal and Behaviour During the Late Quaternary. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01829-7.

- Ramsay, Jacob (2008). Mandarins and Martyrs: The Church and the Nguyen Dynasty in Early Nineteenth-century Vietnam. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-7954-8.

- Richardson, John (1876). A school manual of modern geography. Physical and political. Publisher not identified.

- Schafer, Edward Hetzel (1967), The Vermilion Bird: T'ang Images of the South, Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 9780520011458

- Smith, T. (2007). Britain and the Origins of the Vietnam War: UK Policy in Indo-China, 1943–50. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-0-230-59166-0.

- Taylor, Keith Weller (1983). The Birth of the Vietnam. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07417-0.

- Taylor, Keith W. (2013). A History of the Vietnamese. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107244351.

- Thomas, Martin (2012). Rubber, coolies and communists: In Violence and Colonial Order: Police, Workers and Protest in the European Colonial Empires, 1918–1940 (Critical Perspectives on Empire from Part II – Colonial case studies: French, British and Belgian). pp. 141–176. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139045643.009. ISBN 978-1-139-04564-3.

- Tonnesson, Stein (2011). Vietnam 1946: How the War Began. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-26993-4.

- Tran, Anh Q. (2017). Gods, Heroes, and Ancestors: An Interreligious Encounter in Eighteenth-Century Vietnam. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-067760-2.

- Tucker, Spencer (1999). Vietnam. University of Kentucky Press. ISBN 978-0813121215.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2011). The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: A Political, Social, and Military History, 2nd Edition [4 volumes]: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-961-0.

- Turner, Robert F. (1975). Vietnamese communism, its origins and development. Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University. ISBN 978-0-8179-6431-3.

- Vo, Nghia M. (2011). Saigon: A History. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-8634-2.

- Waite, James (2012). The End of the First Indochina War: A Global History. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-27334-6.

- Walker, Hugh Dyson (2012). East Asia: A New History. ISBN 978-1477265161.

- Willbanks, James H. (2013). Vietnam War Almanac: An In-Depth Guide to the Most Controversial Conflict in American History. Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62636-528-5.

- Woods, L. Shelton (2002). Vietnam: a global studies handbook. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-416-9.

- Yü, Ying-shih (1986), "Han foreign relations", in Twitchett, Denis C.; Fairbank, John King (eds.), The Cambridge History of China: Volume 1, The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC-AD 220, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 377–463

Journal articles and theses

- Crozier, Brian (1955). "The Diem Regime in Southern Vietnam". Far Eastern Survey. 24 (4): 49–56. doi:10.2307/3023970. JSTOR 3023970.

- Gallup, John Luke (2002). "The wage labor market and inequality in Viet Nam in the 1990s". Policy Research Working Paper Series, World Bank. Policy Research Working Papers. doi:10.1596/1813-9450-2896. hdl:10986/19272. S2CID 18598221 – via Research Papers in Economics.

- Gittinger, J. Price (1959). "Communist Land Policy in North Viet Nam". Far Eastern Survey. 28 (8): 113–126. doi:10.2307/3024603. JSTOR 3024603.

- Goodkind, Daniel (1995). "Rising Gender Inequality in Vietnam Since Reunification". Pacific Affairs. 68 (3): 342–359. doi:10.2307/2761129. JSTOR 2761129.

- Hirschman, Charles; Preston, Samuel; Manh Loi, Vu (1995). "Vietnamese Casualties During the American War: A New Estimate". Population and Development Review. 21 (4): 783–812. doi:10.2307/2137774. JSTOR 2137774.

- Matsumura, Hirofumi; Lan Cuong, Nguyen; Kim Thuy, Nguyen; Anezaki, Tomoko (2001). "Dental Morphology of the Early Hoabinian, the Neolithic Da But and the Metal Age Dong Son Civilized Peoples in Vietnam". Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie, e. Schweizerbart'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. 83 (1): 59–73. doi:10.1127/zma/83/2001/59. JSTOR 25757578. PMID 11372468.

- Matsumura, Hirofumi; Yoneda, Minoru; Yukio, Dodo; Oxenham, Marc; et al. (2008). "Terminal Pleistocene human skeleton from Hang Cho Cave, northern Vietnam: implications for the biological affinities of Hoabinhian people". Anthropological Science. 116 (3): 201–217. doi:10.1537/ase.070416. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2018 – via J-STAGE.

- Maspero, Henri (1912). "Études sur la phonétique historique de la langue annamite" [Studies on the phonetic history of the Annamite language]. Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient (in French). 12 (1). doi:10.3406/befeo.1912.2713.

- Ngo, Lan A. (2016). Nguyễn–Catholic History (1770s–1890s) and the Gestation of Vietnamese Catholic National Identity (PDF). Georgetown University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (Thesis). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2018 – via DigitalGeorgetown.

- Nhu Nguyen, Quynh Thi (2016). "The Vietnamese Values System: A Blend of Oriental, Western and Socialist Values" (PDF). International Education Studies. 9 (12). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2018 – via Institute of Education Sciences.

- Obermeyer, Ziad; Murray, Christopher J L; Gakidou, Emmanuela (2008). "Fifty years of violent war deaths from Vietnam to Bosnia: analysis of data from the world health survey programme [Table 3]". BMJ. 336 (7659): 1482–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.a137. PMC 2440905. PMID 18566045.

- Odell, Andrew L.; Castillo, Marlene F. (2008). "Vietnam in a Nutshell: An Historical, Political and Commercial Overview" (PDF). NYBSA International Law Practicum. 21 (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2018 – via Duane Morris.

- Quach Langlet, Tâm (1991). "Charles Fourniau : Annam-Tonkin 1885–1896. Lettrés et paysans vietnamiens face à la conquête coloniale. Travaux du Centre d'Histoire et Civilisations de la péninsule Indochinoise". Bulletin de l'École Française d'Extrême-Orient (in French). 78 – via Persée.