Vikram Samvat

Vikram Samvat (Hindi, Nepali: विक्रम संवत्, IAST: Vikrama Samvat; abbreviated VS) or Bikram Sambat (Nepali, abbreviated as BS; Nepali pronunciation: [bikɾʌm sʌmbʌt] (![]() listen)) and also known as the Vikrami calendar, is the historical Hindu calendar used in the Indian subcontinent. It is the official calendar of Nepal. In India it is used in several states.[1][2] The traditional Vikram Samvat calendar, as used in India, uses lunar months and solar sidereal years. The Nepali Bikram Sambat introduced in 1901 AD, uses a solar tropical year.

listen)) and also known as the Vikrami calendar, is the historical Hindu calendar used in the Indian subcontinent. It is the official calendar of Nepal. In India it is used in several states.[1][2] The traditional Vikram Samvat calendar, as used in India, uses lunar months and solar sidereal years. The Nepali Bikram Sambat introduced in 1901 AD, uses a solar tropical year.

History[]

A number of ancient and medieval inscriptions used the Vikram Samvat. Although it was reportedly named after the legendary king Vikramaditya, Samvatsara in short ‘Samvat ’is a Sanskrit term for ‘year’. King Vikramaditya of Ujjain started Vikram Samvat in 57 BC and it is believed that this calendar follows his victory over the Saka in 56 B.C.

It started in 56 BCE in southern (Amanta) and 57–56 BCE in northern (Purnimanta) systems of the Hindu calendar. The Shukla Paksha in both systems coincides, most festivals occur in the Shukla Paksha. The era is named after King Vikramaditya of India, the era was believed to be based on the commemoration of King Vikramaditya expelling the Sakas from Ujjain. According to the Pratisarga Parvan of Bhavisya Purana, he was the second son of Ujjain's King Gandharvasena of Paramara dynasty. Vikramaditya was born on 102 BC and died on 15 AD.The earliest mention of this era comes from the inscription of King Jaikadeva, who ruled near Okhamandal in Kathiawar State (now Gujarat). The inscription mentions 794 Vikram Samvat corresponding to AD 737 as the date of its installation. [3]

Vikramaditya legend[]

According to popular tradition, King Vikramaditya of Ujjain established the Vikrama Samvat era after defeating the Śakas.

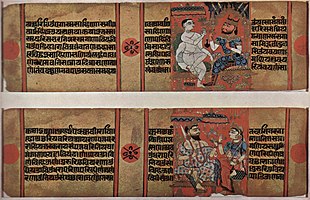

Kalakacharya Kathanaka (An account of the monk Kalakacharya), by the Jain sage Mahesarasuri, gives the following account: Gandharvasena, the then-powerful king of Ujjain, abducted a nun called Sarasvati, who was the sister of the monk. The enraged monk sought the help of the Śaka ruler King Sahi in Sistan. Despite heavy odds but aided by miracles, the Śaka king defeated Gandharvasena and made him a captive. Sarasvati was repatriated, although Gandharvasena himself was forgiven. The defeated king retired to the forest, where he was killed by a tiger. His son, Vikramaditya, being brought up in the forest, had to rule from Pratishthana (modern Paithan in Maharashtra). Later on, Vikramaditya invaded Ujjain and drove away from the Śakas. To commemorate this event, he started a new era called the "Vikrama era". The Ujjain calendar started around 58–56 BCE, and the subsequent Shaka-era calendar was started in 78 CE at Pratishthana.[full citation needed] although it is popularly (and incorrectly) associated with the subsequent king Chandragupta Vikramaditya

Popularity[]

The Vikram Samvat has been used by Hindus and Sikhs.[4] One of several regional Hindu calendars in use on the Indian subcontinent, it is based on twelve synodic lunar months and 365 solar days.[4][5] The lunar year begins with the new moon of the month of Chaitra.[6] This day, known as Chaitra Sukhladi, is a restricted holiday in India.[7][failed verification]

The calendar remains in use by people in Nepal and Hindus of north, west and central India.[8] In south India and portions of east and west India (such as Assam, West Bengal and Gujarat), the Indian national calendar is widely used.[9]

With the arrival of Islamic rule, the Hijri calendar became the official calendar of sultanates and the Mughal Empire. During British colonial rule of the Indian subcontinent, the Gregorian calendar was adopted and is commonly used in urban areas of India.[10] The predominantly-Muslim countries of Pakistan and Bangladesh have used the Islamic calendar since 1947, but older texts included the Vikram Samvat and Gregorian calendars. In 2003, the India-based Sikh Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee controversially adopted the Nanakshahi calendar.[4] The Bikram Sambat is the official calendar of Nepal.[11]

Calendar system[]

Like the Hebrew and Chinese calendars, the Vikram Samvat is lunisolar. [4] In common years, the year is 354 days long,[12] while a leap month (adhik maas) is added in accordance to the Metonic cycle roughly once every three years (or 7 times in a 19-year cycle) to ensure that festivals and crop-related rituals fall in the appropriate season.[4][5] Early Buddhist communities in India adopted the ancient Hindu calendar, followed by the Vikram Samvat and local Buddhist calendars. Buddhist festivals are still scheduled according to a lunar system.[13]

The Vikram Samvat has two systems. It began in 56 BCE in the southern Hindu calendar system (amaanta) and 57–56 BCE in the northern system (purnimaanta). The Shukla Paksha, when most festivals occur, coincides in both systems.[9][14] The lunisolar Vikram Samvat calendar is 56.7 years ahead of the solar Gregorian calendar; the year 2078 BS begins mid-April 2021 CE, and ends mid-April 2022 CE.

The Rana dynasty of Nepal made the Bikram Sambat the official Hindu calendar in 1901 AD, which began as 1958 BS.[15] The new year in Nepal begins with the first day of the month of Baishakh, which usually falls around 13–15 April in the Gregorian calendar and ends with the last day of the month Chaitra. The first day of the new year is a public holiday in Nepal. Bisket Jatra, an annual carnival in Bhaktapur, is also celebrated on Baishakh 1. In 2007, Nepal Sambat was also recognised as a national calendar alongside Bikram Sambat.

In India, the reformulated Saka calendar is officially used (except for computing dates of the traditional festivals). In the Hindi version of the preamble of the constitution of India, the date of its adoption (26 November 1949) is presented in Vikram Samvat as Margsheersh Shukla Saptami Samvat 2006. A call has been made for the Vikram Samvat to replace the Saka calendar as India's official calendar.[16]

New Year[]

- Chaitra Navaratri: the second most celebrated, named after vasanta which means spring. It is observed the lunar month of Chaitra (post-winter, March–April). In many regions the festival falls after spring harvest, and in others during harvest. It also marks the first day of the Hindu calendar, hence also known as the Hindu Lunar New Year according to Vikram Samvat calendar.[17][18]

- Vaisakhi:

- Vaisakhi marks the beginning of Hindu Solar New Year in Punjab, Northern and Central India according to the solar Vikram Samvat calendar.[19][20] and marks the first day of the month of Vaisakha, which is usually celebrated on 13 or 14 April every year and is a historical and religious festival in Hinduism.

- Baisakhi (Nepal): Baisakhi is celebrated as Nepalese New Year[21] because it is the day which marks Hindu Solar New Year[22] as per the solar Nepali Bikram Sambat.

Divisions of a year[]

The Vikram Samvat uses lunar months and solar sidereal years. Because 12 months do not match a sidereal year, correctional months (adhika māsa) are added or (occasionally) subtracted (kshaya masa). A lunar year consists of 12 months, and each month has two fortnights, with a variable duration ranging from 29 to 32 days. The lunar days are called tithis. Each month has 30 tithis, which vary in length from 20 to 27 hours. The waxing phase, beginning with the day after the new moon (amavasya), is called gaura or shukla paksha (the bright or auspicious fortnight). The waning phase is called krishna or vadhya paksha (the dark fortnight, considered inauspicious).[23]

Lunar metrics[]

- A tithi is the time it takes for the longitudinal angle between the Moon and the Sun to increase by 12°.[24] Tithis begin at various times of the day, and vary in duration.

- A paksha (or pakṣa) is a lunar fortnight and consists of 15 tithis.

- A māsa, or lunar month (about 29.5 days), is divided into two paksas.

- A ritu (season) is two māsas.[24]

- An ayana is three ritus.

- A year is two ayanas.[24]

Months[]

The classical Vikram Samvat is generally 57 years ahead of Gregorian Calendar, except during January to April, when it is ahead by 56 years. The month that the new year starts varies by region or sub-culture.

The Nepali BS, like other tropical calendars (such as Bangla) starts with Baisakh.

As of 14 April 2021, it is 2078 BS in the BS calendar. The names of months in the Vikram Samvat in Sanskrit and Nepali,[25][26] with their roughly corresponding Gregorian months, respectively are:

| Vikram Samvat months | Gregorian months |

|---|---|

| Vaiśākha or Baisakh | April–May |

| Jyaiṣṭha or Jestha | May–June |

| Asādha or Asar | June–July |

| Srāvana or Sawan | July–August |

| Bhādrapada or Bhadra or Bhadau | August–September |

| Asvinā or Asoj | September–October |

| Kārtikā or Kartik | October–November |

| Agrahāyaṇa or Mangsir | November–December |

| Pauṣa or Paush | December–January |

| Māgha or Magh | January–February |

| Phālguna or Falgun | February–March |

| Chaitra or Chait | March–April |

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Masatoshi Iguchi (2015). Java Essay: The History and Culture of a Southern Country. TPL. p. 135. ISBN 978-1-78462-885-7.

- ^ Edward Simpson (2007). Muslim Society and the Western Indian Ocean: The Seafarers of Kachchh. Routledge. pp. 113–114. ISBN 978-1-134-18484-2.

- ^ "The tragedy of Vikram Samvat".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Eleanor Nesbitt (2016). Sikhism: a Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. pp. 122–123. ISBN 978-0-19-874557-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Christopher John Fuller (2004). The Camphor Flame: Popular Hinduism and Society in India. Princeton University Press. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-0-69112-04-85.

- ^ Davivajña, Rāma (1996) Muhurtacintāmaṇi. Sagar Publications

- ^ India.gov.in

- ^ Richard Salomon (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the Other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 182–183. ISBN 978-0-19-509984-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Richard Salomon (1398). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 181–183. ISBN 978-0-19-535666-3.

- ^ Tim Harper; Sunil Amrith (2014). Sites of Asian Interaction: Ideas, Networks and Mobility. Cambridge University Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-1-316-09306-1.

- ^ Bal Gopal Shrestha (2012). The Sacred Town of Sankhu: The Anthropology of Newar Ritual, Religion and Society in Nepal. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-1-4438-3825-2.

- ^ Orazio Marucchi (2011). Christian Epigraphy: An Elementary Treatise with a Collection of Ancient Christian Inscriptions Mainly of Roman Origin. Cambridge University Press. p. 289. ISBN 978-0-521-23594-5., Text: "...the lunar year consists of 354 days..."

- ^ Anita Ganeri (2003). Buddhist Festivals Through the Year. BRB. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-1-58340-375-4.

- ^ Ashvini Agrawal (1989). Rise and Fall of the Imperial Guptas. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 174–175. ISBN 978-81-208-0592-7.

- ^ Crump, William D. (25 April 2014). Encyclopedia of New Year's Holidays Worldwide. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-9545-0.

- ^ "Vikram Samvat should be declared national calendar". The Free Press Journal. 15 February 2012. Archived from the original on 26 April 2014. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ^ "Chaitra Navratri 2020: Significance, history behind the nine-day festival and how will it be different this year". The Hindustan Times. 30 March 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ Desk, India TV News (21 March 2015). "Difference between Vasanta and Sharad Navaratri - India TV". www.indiatvnews.com. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ Rinehart, Robin; Rinehart, Robert (2004). Contemporary Hinduism: Ritual, Culture, and Practice. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-905-8.

- ^ Kelly, Aidan A.; Dresser, Peter D.; Ross, Linda M. (1993). Religious Holidays and Calendars: An Encyclopaedic Handbook. Omnigraphics, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-55888-348-2.

- ^ International Commerce. Bureau of International Commerce. 1970.

- ^ Fodor's; Staff, Fodor's Travel Publications, Inc (12 December 1983). India, Nepal and Sri Lanka, 1984. Fodor's Travel Publications. ISBN 978-0-679-01013-5.

- ^ "What Is the Hindu Calendar System?". Learn Religions. Archived from the original on 6 May 2019. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Burgess, Ebenezer Translation of the Sûrya-Siddhânta: A text-book of Hindu astronomy, with notes and an appendix originally published: Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 6, (1860), pp. 141–498, Chapter 14, Verse 12

- ^ Nilsson, Usha (1997). Mira Bai (Rajasthani Poetess). Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-260-0411-9.

- ^ Chatterjee, SK (1990). Indian Calendric System. Government of India. p. 17.

Further reading[]

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Vikramaditya. |

- Harry Falk and Chris Bennett (2009). "Macedonian Intercalary Months and the Era of Azes." Acta Orientalia 70, pp. 197–215.

- "The Dynastic Art of the Kushan", John Rosenfield.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

External links[]

- Punjabi culture

- Time in India

- Specific calendars

- Hindu calendar

- Memorials to Vikramaditya

- Lunisolar calendars

- Calendar eras

- Observances set by the Vikram Samvat calendar