Walla Walla, Washington

Walla Walla, Washington | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of Walla Walla | |

Reynolds–Day Building, Sterling Bank, and Baker Boyer Bank buildings in downtown Walla Walla | |

Flag | |

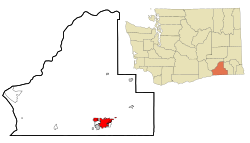

Location of Walla Walla, Washington | |

| Coordinates: 46°3′54″N 118°19′49″W / 46.06500°N 118.33028°WCoordinates: 46°3′54″N 118°19′49″W / 46.06500°N 118.33028°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Washington |

| County | Walla Walla |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager |

| • Body | City council |

| • Mayor | Tom Scribner |

| • City manager | Nabiel Shawa |

| Area | |

| • City | 13.88 sq mi (35.95 km2) |

| • Land | 13.85 sq mi (35.86 km2) |

| • Water | 0.03 sq mi (0.08 km2) |

| Elevation | 942 ft (287 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 31,731 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 32,900 |

| • Density | 2,376.14/sq mi (917.42/km2) |

| • Urban | 55,805 (US: 464th) |

| • Metro | 64,981 (US: 380th) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Code | 99362 |

| Area code | 509 |

| FIPS code | 53-75775 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1512769[4] |

| Website | City of Walla Walla |

Walla Walla is the largest city and county seat of Walla Walla County, Washington, United States.[5] It had a population of 31,731 at the 2010 census, estimated to have increased to 32,900 as of 2019. The population of the city and its two suburbs, the town of College Place and unincorporated Walla Walla East, is about 45,000.[6]

Walla Walla is in the southeastern region of Washington, approximately four hours away from Portland, Oregon, and four and half hours from Seattle. It is located only 6 mi (10 km) north of the Oregon border.

History[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (September 2018) |

Recorded history in this state begins with the establishment of Fort Nez Perce in 1818 by the North West Company to trade with the Walla Walla people and other local Native American groups. At the time, the term "Nez Perce", which is French for pierced nose, was used more broadly than today, and included the Walla Walla in its scope in English usage.[7] Fort Nez Perce had its name shift to Fort Walla Walla. It was located significantly west of the present city.

On September 1, 1836, Marcus Whitman arrived with his wife Narcissa Whitman.[8] Here they established the Whitman Mission in an unsuccessful attempt to convert the local Walla Walla tribe to Christianity. Following a disease epidemic, both were killed in 1847 by the Cayuse who thought that the missionaries were poisoning the native peoples. Whitman College was established in their honor.

On July 24, 1846, Pope Pius IX established the Diocese of Walla Walla and appointed Augustin-Magloire Blanchet to become the first Bishop of Walla Walla. The diocese was short-lived as Bishop Blanchet fled to St. Paul, Oregon, after the Whitman Massacre. In 1850, the Diocese of Nesqually was established in Vancouver and in 1853 the Diocese of Walla Walla was suppressed and absorbed into the Diocese of Nesqually. Today, the Diocese of Walla Walla is a titular see currently held by Witold Mroziewski, an auxiliary bishop of Brooklyn, New York.[9]

The original North West Company and later Hudson's Bay Company Fort Nez Percés fur trading outpost, became a major stopping point for migrants moving west to Oregon Country. The fort has been restored with many of the original buildings preserved. The current Fort Walla Walla contains these buildings, albeit in a different location from the original, as well as a museum about the early settlers' lives.

The origins of Walla Walla at its present site begin with the establishment of Fort Walla Walla by the United States Army here in 1856.[10] The Walla Walla River, where it adjoins the Columbia River, was the starting point for the Mullan Road, constructed between 1859 and 1860 by US Army Lieut. John Mullan, connecting the head of navigation on the Columbia at Walla Walla (i.e., the west coast of the United States) with the head of navigation on the Missouri-Mississippi (that is, the east and gulf coasts of the U.S.) at Fort Benton, Montana.

Walla Walla was incorporated on January 11, 1862.[11] As a result of a gold rush in Idaho, during this decade the city became the largest community in the territory of Washington, at one point slated to be the new state's capital. Following this period of rapid growth, agriculture became the city's primary industry. Baker Boyer Bank, the oldest bank in the state of Washington, was founded in Walla Walla in 1869.

In 1936, Walla Walla and surrounding areas were struck by the magnitude 6.1 State Line earthquake. Residents reported hearing a moderate rumbling immediately before the shock. There was significant damage in the area, and aftershocks were felt for several months following.[12]

In 2001 Walla Walla was a Great American Main Street Award winner for the transformation and preservation of its once dilapidated main street.[13] In July 2011, USA Today selected Walla Walla as the friendliest small city in the United States.[14] Walla Walla was also named Friendliest Small Town in America the same year as part of Rand McNally's annual Best of the Road contest. In 2012 and 2013 Walla Walla was a runner-up in the best food category for the Best of the Road.[15][16] Downtown Walla Walla was awarded a Great Places in America Great Neighborhood designation in 2012 by the American Planning Association.[17][18]

Etymology[]

Tourists to Walla Walla are often told that it is a "town so nice they named it twice".[19] Some locals and Walla Walla natives often refer to the city in text form with "W2".[20] Walla Walla is a Native American name that means "Place of Many Waters" because the original settlement was at the junction of the Snake and Columbia rivers. The original name of the town was Steptoeville, named after Colonel Edward Steptoe.[21] In 1855 the name was changed to Waiilatpu,[22] and then by 1859 had been changed again, this time to the name it holds today. Walla Walla is humorously mentioned in The Three Stooges and Looney Tunes.[23][specify]

Geography and climate[]

Walla Walla is located in the Walla Walla Valley, with the rolling Palouse hills and the Blue Mountains to the east of town. Various creeks meander through town before combining to become the Walla Walla River, which drains into the Columbia River about 30 miles (50 km) west of town. The city lies in the rain shadow of the Cascade Mountains, so annual precipitation is fairly low.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 12.84 square miles (33.26 km2), of which 12.81 square miles (33.18 km2) is land and 0.03 square miles (0.08 km2) is water.[24][25]

Walla Walla has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate according to the Köppen climate classification system (Köppen Csa). It is one of the northernmost locations in North America to qualify as having such a climate. In contrast to most other locations having this climate type in North America, Walla Walla can experience fairly cold winter conditions, though they are still relatively mild for its latitude and inland location.

| hideClimate data for Walla Walla, Washington (Walla Walla Regional Airport), 1991–2020 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 70 (21) |

75 (24) |

79 (26) |

96 (36) |

100 (38) |

116 (47) |

114 (46) |

114 (46) |

104 (40) |

89 (32) |

80 (27) |

68 (20) |

116 (47) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 41.9 (5.5) |

46.5 (8.1) |

55.8 (13.2) |

62.5 (16.9) |

71.4 (21.9) |

79.0 (26.1) |

90.1 (32.3) |

88.6 (31.4) |

78.5 (25.8) |

63.4 (17.4) |

49.2 (9.6) |

41.0 (5.0) |

64.0 (17.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 36.3 (2.4) |

39.7 (4.3) |

46.8 (8.2) |

52.5 (11.4) |

60.4 (15.8) |

67.0 (19.4) |

76.3 (24.6) |

75.2 (24.0) |

66.2 (19.0) |

53.9 (12.2) |

43.9 (6.6) |

35.6 (2.0) |

54.3 (12.4) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 30.7 (−0.7) |

32.9 (0.5) |

37.8 (3.2) |

42.5 (5.8) |

49.3 (9.6) |

55.1 (12.8) |

62.4 (16.9) |

61.7 (16.5) |

53.9 (12.2) |

43.9 (6.6) |

35.6 (2.0) |

30.2 (−1.0) |

44.7 (7.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −18 (−28) |

−16 (−27) |

4 (−16) |

20 (−7) |

26 (−3) |

36 (2) |

40 (4) |

42 (6) |

32 (0) |

19 (−7) |

−11 (−24) |

−24 (−31) |

−24 (−31) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.10 (53) |

1.59 (40) |

2.11 (54) |

1.98 (50) |

2.07 (53) |

1.24 (31) |

0.47 (12) |

0.40 (10) |

0.64 (16) |

1.66 (42) |

2.25 (57) |

2.23 (57) |

18.74 (476) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.0 (2.5) |

2.2 (5.6) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.3 (0.76) |

2.7 (6.9) |

6.5 (16.52) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 13.0 | 10.5 | 12.3 | 10.2 | 9.6 | 7.3 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 3.9 | 7.8 | 13.9 | 13.2 | 107.6 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 2.5 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 3.3 | 9.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 50.4 | 83.4 | 173.8 | 221.7 | 288.5 | 326.3 | 384.5 | 344.4 | 268.8 | 199.2 | 67.8 | 40.3 | 2,449.2 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 18.0 | 28.6 | 47.0 | 54.4 | 62.1 | 69.1 | 80.7 | 78.7 | 71.6 | 59.0 | 24.0 | 15.0 | 50.7 |

| Source 1: NOAA[26][27] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather.com[citation needed] | |||||||||||||

Demographics[]

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 1,394 | — | |

| 1880 | 3,588 | 157.4% | |

| 1890 | 4,709 | 31.2% | |

| 1900 | 10,049 | 113.4% | |

| 1910 | 19,364 | 92.7% | |

| 1920 | 15,503 | −19.9% | |

| 1930 | 15,976 | 3.1% | |

| 1940 | 18,109 | 13.4% | |

| 1950 | 24,102 | 33.1% | |

| 1960 | 24,536 | 1.8% | |

| 1970 | 23,619 | −3.7% | |

| 1980 | 25,618 | 8.5% | |

| 1990 | 26,478 | 3.4% | |

| 2000 | 29,686 | 12.1% | |

| 2010 | 31,731 | 6.9% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 32,900 | [2] | 3.7% |

2010 census[]

As of the census[3] of 2010, there were 31,731 people, 11,537 households, and 6,834 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,477.0 inhabitants per square mile (956.4/km2). There were 12,514 housing units at an average density of 976.9 per square mile (377.2/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 81.6% White, 2.7% African American, 1.3% Native American, 1.4% Asian, 0.3% Pacific Islander, 9.1% from other races, and 3.6% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 22.0% of the population.

There were 11,537 households, of which 30.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 42.6% were married couples living together, 12.0% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.7% had a male householder with no wife present, and 40.8% were other forms of households. 33.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.43 and the average family size was 3.10.

The median age in the city was 34.4 years. 22% of residents were under the age of 18; 14.5% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 26.2% were from 25 to 44; 23.1% were from 45 to 64; and 14% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 51.9% male and 48.1% female.

2000 census[]

As of the census of 2000, there were 29,686 people, 10,596 households, and 6,527 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,744.9 people per square mile (1,059.3/km2). There were 11,400 housing units at an average density of 1,054.1 per square mile (406.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 83.79% White, 2.58% African American, 1.05% Native American, 1.24% Asian, 0.23% Pacific Islander, 8.26% from other races, and 2.85% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 17.42% of the population.

There were 10,596 households, of which 30.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 46.4% were married couples living together, 11.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 38.4% were other forms of households. 31.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 15.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.44 and the average family size was 3.08.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 21.8% under the age of 18, 14.2% from 18 to 24, 26.5% from 25 to 44, 17.5% from 45 to 64, and 20.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 108.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 109.1 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $31,855, and the median income for a family was $40,856. Men had a median income of $31,753 versus $23,889 for women. The per capita income for the city was $15,792. About 13.1% of families and 18.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 22.8% of those under the age of 18 and 10.5% of those aged 65 and older.

Economy and infrastructure[]

Agriculture[]

Though wheat is still a big crop, vineyards and wineries have become economically important over the last three decades.[29] In summer 2020, there were over 120 wineries in the greater Walla Walla area. Following the wine boom, the town has developed several fine dining establishments and luxury hotels. The Marcus Whitman Hotel, originally opened in 1928, was renovated with original fixtures and furnitures. It is the tallest building in the city, at 13 stories.

The Walla Walla Sweet Onion is another crop with a rich tradition. Over a century ago on the Island of Corsica, off the west coast of Italy, a French soldier named Peter Pieri found an Italian sweet onion seed and brought it to the Walla Walla Valley. Impressed by the new onion's winter hardiness, Pieri, and the Italian immigrant farmers who comprised much of Walla Walla's gardening industry, harvested the seed. The sweet onion developed over several generations through the process of selecting onions from each year's crop, targeting sweetness, size and round shape. The Walla Walla Sweet Onion is designated under federal law as a protected agricultural crop. In 2007 the Walla Walla Sweet Onion became Washington's official state vegetable.[30] There is also a Walla Walla Sweet Onion Festival, held annually in July. Walla Walla Sweet Onions have low sulfur content (about half that of an ordinary yellow onion) and are 90 percent water.

Walla Walla currently has two farmers markets, both held from May until October. The first is located on the corner of 4th and Main, and is coordinated by the Downtown Walla Walla Foundation. The other is at the Walla Walla County Fairgrounds on S. Ninth Ave, run by the WW Valley Farmer's Market.[31]

Wine industry[]

Walla Walla has experienced an expansion in its wine industry in recent decades, culminating in the area being named "Best Wine Region (2020)" in USA Today's Reader Choice Awards.[32] Several local wineries have received top scores from wine publications such as Wine Spectator, The Wine Advocate and Wine and Spirits. L'Ecole 41, Woodward Canyon, Waterbrook Winery and Leonetti Cellar were the pioneers starting in the 1970s and 1980s. Although most of the early recognition went to the wines made from Merlot and Cabernet, Syrah is fast becoming a star varietal in this appellation.[33] Overall, there are more than 120 wineries in the Walla Walla area, which collectively generate over $100 million for the valley annually.[34][35]

Walla Walla Community College offers an associate degree (AAAS) in winemaking and grape growing through its Center for Enology and Viticulture, which operates its own commercial winery, College Cellars.[36]

One challenge to growing grapes in Walla Walla Valley is the risk of a killing freeze during the winter. On average these happen once every six or seven years; the penultimate occurrence (in 2004) destroyed about 75% of the wine grape crop in the valley. In November 2010 the valley was again hit with a killing frost, leading to a 28% decline in Cabernet Sauvignon production, a 20% decline in red grape production, and an overall decline in production of 11% (red and white varietals).[37]

Corrections industry[]

The second-largest prison in Washington, after nearby Coyote Ridge Corrections Center in Connell, is the Washington State Penitentiary (WSP) located in Walla Walla, at 1313 North 13th. Originally opened in 1886, it now houses about 2,000 offenders.[38] In addition, there are about 1000 staff members. In 2005, the financial benefit to the local economy was estimated to be about $55 million through salaries, medical services, utilities, and local purchases. The penitentiary is undergoing an extensive expansion project that will increase the prison capacity to 2,500 violent offenders and double the staff size.[39]

Until October 11, 2018, Washington was a death penalty state, and occasional executions took place at the state penitentiary; the last execution took place on September 10, 2010.[40][41] Washington was also one of the last two states to allow hanging as a choice when sentenced to death[42] (the other being New Hampshire); there has not been a hanging since May 1994 (the default method of execution was changed to lethal injection in 1996). Washington was the last state with an active gallows.[43]

Healthcare[]

Walla Walla is served by two health care institutions: St. Mary Medical Center (part of the Catholic Providence Health System) and the Jonathan M. Wainwright on the grounds of the old Fort Walla Walla and WWII training facility.

Transportation[]

Transportation to Walla Walla includes service by air through Walla Walla Regional Airport, several railroads, and highway access primarily from U.S. Route 12. The Washington State Department of Transportation is engaged in a long-term process of widening this road into a four-lane divided highway between Pasco and Walla Walla, with major portions scheduled to be complete in 2022.[44] The highway also acts as the main gateway to Interstates 82 and 84, which run to the west and south, respectively.[45] State Route 125 runs through the city, north to State Route 124 in Prescott and south to Milton-Freewater, Oregon, becoming Oregon Highway 11 at the state line.[citation needed]

There are four major bus services in the area connecting the region's cities. Walla Walla and nearby College Place are served by Valley Transit, a typical multi-route city bus service. The city of Milton-Freewater, OR has a single-line bus service with several stops in town with two stops in College Place and five in Walla Walla. Travel Washington's Grape Line is a 104-mile (167 km) intercity service between Walla Walla and Pasco that runs three times a day. Finally, Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation operates a Kayak bus to Pendleton, with four trips each weekday and two trips each Saturday via its Walla Walla Whistler route.[46]

Sports[]

Walla Walla is home of the Walla Walla Sweets, a summer collegiate baseball team that plays in the West Coast League. The league comprises college players and prospects working towards a professional baseball career. Teams are located in British Columbia, Oregon and Washington. Sweets home games have been played at Borleske Stadium in Walla Walla, since their first season in 2010. In only their second season the Sweets played in the WCL Championship game, ultimately losing to the Corvallis Knights. In 2013, the Sweets won their first North Division title with the second best win-loss record in the WCL. The Sweets lost their North Division playoff series to the Wenatchee Applesox that year.

There also is a women's flat track roller derby league called the Walla Walla Sweets Rollergirls, their practices and games are played at the Walla Walla YMCA.

Walla Walla is the location of Tour of Walla Walla, a four-stage road cycling race held annually in April. The races are held in Walla Walla and in the Palouse hills of nearby Waitsburg. The stages include two road races, a time trial, and a criterium race.[47]

The annual Walla Walla Marathon takes place in October and includes a full marathon, half-marathon, and 10k race. The full marathon is a Boston Marathon Qualifier.[48] The race route winds through the streets of the city of Walla Walla and the country roads outside of town, often running past several of the region's many estate vineyards.

Fine and performing arts[]

The Walla Walla Valley boasts a number of fine and performing arts organizations and venues.

- The Walla Walla Valley Bands were formed in 1989 and currently boasts a Concert Band of more than 70 and two Jazz Ensembles. The group rehearses weekly on Tuesday nights at the Walla Walla Valley Adventist Academy in nearby College Place.

- The Walla Walla Symphony began in 1906 and performs a season of about six concerts per year at Whitman College's Cordiner Hall.

- The Walla Walla Chamber Music Festival is held twice a year and features guest musical ensembles playing classical chamber music in various small venues throughout town. The summer festival includes performances for almost the whole month of June. The winter festival is a small-scale version of the summer program, it is held in mid-January.[49]

- Shakespeare Walla Walla is a non-profit organization that hosts a summer Shakespeare festival in Walla Walla. They often bring Shakespeare troupes from Seattle and elsewhere to perform about four plays per year. In the past this was done at the Fort Walla Walla Amphitheater, but more recently at the GESA Powerhouse Theatre.[50]

- The GESA Powerhouse Theatre opened in 2011 in Walla Walla; it was originally the Walla Walla gas plant, hence its name. Its dimensions closely resemble the Blackfriars Theatre once used by William Shakespeare.[51] The venue is used by Shakespeare Walla Walla as well as host to various concerts and other performing arts events throughout the year.

- The Little Theatre of Walla Walla began in 1944 and moved into its current building on Sumach St. in 1948 where it has performed various plays to this day.[52]

- The Walla Walla Choral Society began in 1980 and performs a season of three or four concerts per year in various locations around the Walla Walla Valley.

- Fort Walla Walla Amphitheater is a disused open-air stage with bench seating on the grounds of the Fort Walla Walla Park, next to . It formerly hosted Shakespeare Walla Walla productions and the Walla Walla Community College Summer Musical.

In addition, the area's three colleges—Whitman College, Walla Walla University and Walla Walla Community College as well as its largest public high school—Walla Walla High School—stage theater and music performances.

Education[]

Walla Walla is primarily served by Walla Walla Public Schools, which includes seven elementary schools (one is in Dixie, six of them are K-5 with one of these being PreK-5), two middle schools, one traditional high school (colloquially Wa-Hi), and two alternative high schools (Lincoln and Opportunity). There is also Homelink, an alternative K-8 education program which is a hybrid of homeschooling and public school programs.[53]

There are several private Christian schools in the area. These include:

- The Walla Walla Catholic Schools (Assumption K-8 School and DeSales High School)

- Liberty Christian School, non-denominational

- Rogers Adventist School and Walla Walla Valley Academy, in nearby College Place, both of Seventh-day Adventist affiliation

- Saint Basil Academy of Classical Studies (K-8)

In addition to these, there are three colleges in the area:

- Walla Walla Community College, co-winner of the 2013 Aspen Prize for Community College Excellence[54]

- Whitman College, an independent liberal arts college

- Walla Walla University, in nearby College Place, Washington, affiliated with the Seventh-day Adventist denomination

Sister cities[]

In 1972, Walla Walla established a sister city relationship with Sasayama (now named Tamba-Sasayama), Japan. The two cities have since named roads after their counterpart sister city. Walla Walla has also hosted exchange students from Tamba-Sasayama since 1994 for a two-week home-stay experience. Yearlong high school student exchanges between the cities have occurred several times in the past. Cultural/art exchanges involving music, dance, and various art mediums have also occurred. The Walla Walla Sister City Committee has been the recipient of the Washington State Sister City Association Peace Prize in 2011 and 2014 for their involvement in promoting peace, cultural understanding and friendship.[55][56][57]

Notable people[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2019) |

- Burl Barer, broadcaster and author

- Drew Bledsoe, NFL quarterback

- Hunter Hillenmeyer, former Chicago Bears player

- Richard Arthur Bogle, businessman and rancher

- Walter Brattain, Nobel Prize winner and co-inventor of the transistor

- Evelyn Evelyn, baroque pop duo created by Amanda Palmer and Jason Webley

- Robert Brode, physicist

- Wallace R. Brode, scientist

- Robert Clodius, educator and university administrator

- Alex Deccio, politician

- Eddie Feigner, softball player

- Bert Hadley, actor and makeup artist

- Alan W. Jones. US Army major general[58][59]

- Charly Martin, NFL player[60]

- Edward P. Morgan, television and newspaper journalist

- Walt Minnick, U.S. Congressman

- Mikha'il Na'ima, writer and philosopher

- Eric O'Flaherty, MLB player[61]

- Charles Potts, poet and publisher

- Hope Summers, actress

- Connor Trinneer, actor

- Jonathan Wainwright, U.S. general

- Ferris Webster, film editor

- Adam West, television and film actor; the city celebrates an "Adam West Day" each year on September 19.[62][63]

- Hamza Yusuf, Islamic scholar

See also[]

- List of reduplicated place names

- Blue Mountain Mall

- 1936 State Line earthquake

References[]

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places in Washington: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019". United States Census Bureau. May 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "Official Population Estimates". Washington State Office of Financial Management. Retrieved December 24, 2013.

- ^ Alvin M. Josephy, The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest, Abridged Edition (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965), p. 51

- ^ "National Park Service: Whitman Mission". Nps.gov. November 19, 2012. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ "Titular Episcopal See of Walla Walla". GCatholic. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ^ Josephy, The Nez Perce, p. 367

- ^ "City of Walla Walla, Community Information". Ci.walla-walla.wa.us. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ "WA/OR - United States Earthquakes, 1936". Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ^ "Great American Main Street Award".

- ^ Bly, Laura (July 21, 2011). "USA Today".

- ^ "Best of the Road Walla Walla profile".

- ^ "2011 and 2012 Best of the Road contests".

- ^ https://records.wallawallawa.gov:9443/agenda_publish.cfm?id=&mt=ALL&get_month=10&get_year=2012&dsp=agm&seq=279&rev=0&ag=43&ln=1259&nseq=288&nrev=0&pseq=&prev=#ReturnTo1259

- ^ "Downtown Walla Walla: Walla Walla, Washington".

- ^ Beyette, Beverly (December 23, 2004). "Here's to you, Walla Walla". The Seattle Times.

- ^ Reed, Story and photos by Diane. "What's new in W2". Union-Bulletin.com. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ "Travel – Walla Walla, Washington Introduction : Overview". NWsource. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ "Lyman's History of old Walla Walla County, Vol. 1 (of 2) Embracing Walla Walla, Columbia, Garfield and Asotin counties". Retrieved March 26, 2017.

- ^ "Looney Tunes: Abracadabra, I'm an Umpire!". WB Kids (via YouTube). Retrieved August 15, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 17, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access: Walla Walla Regional Airport, Washington". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ^ Hillhouse, Vicki. "Viticultural area celebrates 30th year". WW Union-Bulletin. Retrieved June 22, 2014.

- ^ "The Spokesman-Review Apr 6, 2007". April 5, 2007. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ Diaz, Alfred. "Walla Walla Doubles up on Farmers Markets". WW Union-Bulletin. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ^ "Best Wine Region Winners (2020) | USA TODAY 10Best".

- ^ Walla Walla Valley Wine Alliance website - http://wallawallawine.com/

- ^ "2013 List of Washington State Wineries". Go Taste Wine, LLC. Retrieved December 24, 2013.

- ^ Hollander, Catherine. "How Wine Growing in Walla Walla Supports the Economy". National Journal. Retrieved December 24, 2013.

- ^ College Cellars website - http://www.collegecellars.com

- ^ Sean Sullivan's Washington Wine Report - http://www.wawinereport.com/2012/02/cabernet-sauvignon-production-down-28.html

- ^ "Washington Department of Corrections, WSP page".

- ^ "The Pioneer (Whitman College) article on the initial expansion". The Pioneer (Whitman College). Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ "Seattle Times article, execution of Cal Cobrun Brown". The Seattle Times.

- ^ Clarridge, Christine; Kamb, Lewis (October 11, 2018). "Death penalty struck down by Washington Supreme Court, taking 8 men off death row". The Seattle Times. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- ^ "Section 630.5, Procedures in Capital Murder". Retrieved April 27, 2006.

- ^ Maria L. La Ganga (February 11, 2014). "Washington state governor declares moratorium on death penalty". LA Times.

- ^ "US 12 - Nine Mile Hill to Frenchtown Vic - Build New Highway". Washington State Department of Transportation. December 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ O'Boyle, Robert; Knutson, Kathleen (October 23, 1987). "WW's remoteness poses problem". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. p. 2.

- ^ http://ctuir.org/system/files/Walla%20Walla%20Whistler_14.pdf

- ^ "Tour of Walla Walla". Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ "Walla Walla Multisports webpage". Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ "Walla Walla Chamber Music Festival Schedule". Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ^ "Past Performances". Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ^ "History of the Powerhouse Theatre". Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ^ "History of the Little Theatre".

- ^ "Walla Walla Public Schools Website". Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ "Aspen Institute, 2013 Aspen Prize". Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ "Walla Walla-Sasayama Sister Cities Inc". Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "WW Union-Bulletin Article on the 2012 Exchanges". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "Walla Walla, sister city Tamba-Sasayama benefit through connection". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- ^ "Alan W. Jones is Promoted". The Spokesman-Review. Spokane, WA. August 28, 1918. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Morelock, J. D. (1994). Generals of the Ardennes: American Leadership in the Battle of the Bulge. Washington, DC: National Defense University Press. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-16-042069-6 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ 404 Error

- ^ "Eric O'Flaherty". Baseball Reference. August 16, 2006. Retrieved April 11, 2015.

- ^ "Holy Hometown Hero, Batman! It's Adam West Day In Walla Walla | Northwest Public Broadcasting". Northwest Public Broadcasting. September 14, 2018. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- ^ "Walla Walla Announces Second Annual 'Adam West Day'". DC. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

Further reading[]

- MacGibbon, Elma (1904). Leaves of knowledge. Shaw & Borden Co. Available online through the Washington State Library's Classics in Washington History collection Elma MacGibbon's reminiscences of her travels in the United States starting in 1898, which were mainly in Oregon and Washington. Includes chapter "Walla Walla and southeastern Washington."

- Bennett, Robert A. Walla Walla: Portrait of a Western Town, 1804–1899. Walla Walla: Frontier Press Books, c. 1980.

- Gilbert, Frank T. Historic Sketches: Walla Walla, Columbia and Garfield Counties, Washington Territory. Portland, Oregon: A.G. Walling Printing

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Walla Walla, Washington. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Walla Walla. |

- Walla Walla, Washington

- Cities in Washington (state)

- Cities in Walla Walla County, Washington

- Washington (state) wine

- County seats in Washington (state)

- Populated places established in 1856

- 1856 establishments in the United States