Waltz with Bashir

| Waltz with Bashir | |

|---|---|

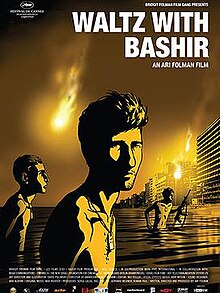

Theatrical release poster | |

| Original title | ואלס עם באשיר |

| Directed by | Ari Folman |

| Written by | Ari Folman |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | Ari Folman |

| Edited by | Nili Feller |

| Music by | Max Richter |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Sony Pictures Classics |

Release date |

|

Running time | 90 minutes[1] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | Hebrew |

| Budget | $2 million[2] |

| Box office | $11,125,849[3] |

Waltz with Bashir (Hebrew: ואלס עם באשיר, translit. Vals Im Bashir) is a 2008 Israeli adult animated war documentary drama film written, produced and directed by Ari Folman. It depicts Folman in search of his lost memories of his experience as a soldier in the 1982 Lebanon War.[4]

This film and $9.99, also released in 2008, are the first Israeli animated feature-length films released theatrically since Joseph the Dreamer (1962).

Waltz with Bashir premiered at the 2008 Cannes Film Festival where it entered the competition for the Palme d'Or, and since then has won and been nominated for many additional important awards while receiving wide acclaim from critics and audience alike, which has praised its themes, animation, direction, story and editing. It has grossed over $11 million, winning numerous awards including the Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film,[5] an NSFC Award for Best Film, a César Award for Best Foreign Film and an IDA Award for Feature Documentary, and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film,[6] a BAFTA Award for Best Film Not in the English Language and an Annie Award for Best Animated Feature.

Plot[]

In 1982, Ari Folman was a 19-year-old IDF infantry soldier. In 2006, he meets with a friend from that period named Boaz, who tells him of the nightmares he is having, which are connected to his experiences from the Lebanon War. Boaz describes 26 madly angry dogs, running towards his house through Tel Aviv main streets, destroying everything in their way. Boaz explains that during the war, his role was to shoot the dogs when the unit infiltrated villages at night, so that these dogs not alarm the village of their arrival, and so the dogs in his dream are the very dogs he himself has killed. Boaz further explains he was chosen to do his job as he was showing a special difficulty to shoot people. Folman is surprised to find that he recalls nothing from that period. Later that night he has a vision from the night of the Sabra and Shatila massacre, the reality of which he is unable to clearly recall. In his memory, he and his soldier comrades are bathing at night by the seaside in Beirut under the light of flares descending over the city.

Folman rushes off to meet a childhood friend, who is a professional therapist. His friend advises him to seek out others who were in Beirut at the same time, to understand what happened there and to revive his own memories. The friend further explains that as for the nature of human memory, the vision might not be based on events which actually occurred. Later on, he explains to Folman that even though the vision might be an hallucination, the vision still deals with matters of great importance for his inner world.

Folman converses with friends and other soldiers who served in the war, among others a psychologist, and Israeli TV reporter Ron Ben-Yishai, who covered Beirut at the time. Folman eventually realizes that he "was in the second or third ring" of soldiers surrounding the Palestinian refugee camp where the carnage was perpetrated, and that he was among those soldiers firing flares into the sky to illuminate the refugee camp for the Lebanese Christian Phalange militia perpetrating the massacre inside. He concludes that his amnesia stemmed from his feeling as a teenage soldier that he was as guilty of the massacre as those who actually carried it out. The film ends with animation dissolving into actual footage of the aftermath of the massacre.

Cast[]

The film contains both completely fictional characters and adaptations of actual people.

- Ari Folman as himself, an Israeli filmmaker who recently finished his military reserve service. Some twenty years before, he served in the IDF during the Lebanon War.

- Miki Leon as Boaz Rein-Buskila, an accountant and Israeli Lebanon War veteran suffering from nightmares.

- Ori Sivan as himself, an Israeli filmmaker who previously co-directed two films with Folman and is his long-time friend.

- Yehezkel Lazarov as Carmi Can'an, an Israeli Lebanon War veteran who once was Folman's friend and now lives in the Netherlands. Carmi chose to be a combat soldier to prove his masculinity, but testifies that, after the war, "he could be nobody" - a response to Folman's remark that he (Can'an) was expected to excel in science.

- Ronny Dayag, an Israeli Lebanon War veteran and high food engineer. During the war, he was a Merkava tank crewman. Dayag testifies that instead of returning fire when the commander of his tank was shot, he and his crew were shocked and tried to escape. His battalion left, but Dayag felt as if it was him who abandoned his battalion, because he did not act as a proper soldier.

- Shmuel Frenkel, an Israeli Lebanon War veteran. During the war he was the commander of an infantry unit. By interviewing Frenkel, Folman understands that his mind deleted and repressed the fact his company confronted a boy with an RPG, whom they were forced to kill. Later on, Frenkel is shown in a scene where the soldiers are under surprise enemy fire from Beirut's rooftops by the shore. Frenkel seemingly lives up to the ideal, but this is depicted as "some sort of trance", when he forcefully takes his fellow's MAG and "waltzes" between enemy bullets, with Bashir's image in the background.

- Zahava Solomon, an Israeli psychologist and researcher in the field of psychological trauma. Zahava provides professional analysis for some events in the movie, using clinical terms. For example, Zahava explains that Folman's confrontation with the RPG kid was forgotten because his brain used a defence mechanism called dissociation. She further illustrates the mechanism with an example of a past patient of hers, who was a photographer in that war. At some point, his dissociation ceased to work and he lost his mind.

- Ron Ben-Yishai, an Israeli journalist who was the first to cover the massacre.

- Dror Harazi, an Israeli Lebanon War veteran. During the war, he commanded a tank stationed outside the Shatila refugee camp.

Title[]

The film takes its title from a scene in which Shmuel Frenkel, one of the interviewees and the commander of Folman's infantry unit at the time of the film's events, grabs a general purpose machine gun and "dances an insane waltz" (to the tune of Chopin's Waltz in C-sharp minor) amid heavy enemy fire on a Beirut street festooned with huge posters of Bashir Gemayel. The title also refers to Israel's short-lived political waltz with Bashir Gemayel as president of Lebanon.[7]

Production[]

The film took four years to complete. It is unusual in it being a feature-length documentary made almost entirely by the means of animation. It combines classical music, 1980s music, realistic graphics, and surrealistic scenes together with illustrations similar to comics. The entire film is animated, excluding one short segment of news archive footage.

The animation, with its dark hues representing the overall feel of the film, uses a unique style invented by Yoni Goodman at the Bridgit Folman Film Gang studio in Israel. The technique is often confused with rotoscoping, an animation style that uses drawings over live footage, but is actually a combination of Adobe Flash cutouts and classic animation.[8] Each drawing was sliced into hundreds of pieces which were moved in relation to one another, thus creating the illusion of movement. The film was first shot in a sound studio as a 90-minute video and then transferred to a storyboard. From there 2,300 original illustrations were drawn based on the storyboard, which together formed the actual film scenes using Flash animation, classic animation, and 3D technologies.[9]

The original soundtrack was composed by minimalist electronic musician Max Richter while the featured songs are by OMD ("Enola Gay"), PiL ("This is Not a Love Song"), Navadey Haukaf (נוודי האוכף "Good Morning Lebanon", written for the film), Haclique ("Incubator"), and Zeev Tene (a remake of the Cake song "I Bombed Korea", retitled "Beirut"). Some reviewers have viewed the music as playing an active role as commentator on events instead of simple accompaniment.[10]

The comics medium, in particular Joe Sacco,[11] the novels Catch-22, The Adventures of Wesley Jackson, and Slaughterhouse-Five,[12] and painter Otto Dix[13] were mentioned by Folman and art director David Polonsky as influences on the film. The film itself was adapted into a graphic novel in 2009.[14]

Release[]

Waltz with Bashir opened in the United States on 25 December 2008 in a mere five theaters, where it grossed $50,021 in the first weekend. By the end of its run on 14 May 2009, the film had grossed $2,283,849 in the domestic box office. Overseas, Waltz earned $8,842,000 for a worldwide total of $11,125,849.[3]

Critical response[]

As of May 2021, the film holds a 96% "fresh" rating on review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes based on 153 critics for an average of 8.40/10; the general consensus states: "A wholly innovative, original, and vital history lesson, with pioneering animation, Waltz With Bashir delivers its message about the Middle East in a mesmerizing fashion."[15] On Metacritic, the film holds a 91/100 based on 33 critics, indicating “universal acclaim”.

IndieWire named the film the tenth best of the year, based on the site's annual survey of 100 film critics. Xan Brooks of The Guardian called it "an extraordinary, harrowing, provocative picture."[16] The film was praised for "inventing a new cinematographic language" at the Tokyo Filmex festival.[17] The World Socialist Web Site's David Walsh described it as a "painfully honest" anti-war film and "one of the most extraordinary and haunting films at the Toronto film festival."[18] Despite the positive critical reception, the film was only moderately commercially successful in Israel itself.[4]

Several writers described it as part of the Israeli "shooting and crying" tradition (where soldiers express remorse about their actions but do not do anything concrete to remedy the situation), but Folman disputed this.[19]

Lebanon screening[]

The film is banned in some Arab countries (including Lebanon), with the most harsh critics in Lebanon, as the film depicts a vague and violent time in Lebanon's history. A movement of bloggers, among them the Lebanese Inner Circle, +961 and others have rebelled against the Lebanese government's ban of the film, and have managed to get the film seen by local Lebanese critics, in defiance of their government's request on banning it. The film was privately screened in January 2009 in Beirut in front of 90 people.[20] Since then many screenings have taken place. Unofficial copies are also available in the country. Folman saw the screening as a source of great pride: "I was overwhelmed and excited. I wish I could have been there. I wish one day I'll be able to present the film myself in Beirut. For me, it will be the happiest day of my life."[21]

Top ten lists[]

The film appeared on many critics' top ten lists of the best films of 2008.[22]

|

|

It was also ranked #34 in Empire magazine's "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema" in 2010,[25] and #4 in Current TV's "50 Documentaries to See Before You Die" in 2011.

Awards and nominations[]

Waltz with Bashir became the first animated film to have received a nomination for an Academy Award and the second for the Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film (France's Persepolis was the first a year prior).[26] Also the first R-rated animated film to be considered for those honors. It also became the first Israeli winner of the Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film since The Policeman (1971), and the first documentary film to win the award.[27]

It was unsuccessfully submitted for an Academy Award for Best Animated Feature nomination, and became ineligible for the Academy Award for Documentary Feature when the Academy announced its new rule to nominate only documentaries which have had a qualifying run in both New York and Los Angeles by 31 August.[28]

The film was also included in the National Board of Review's Top Foreign Films list. Folman won the WGA's Best Documentary Feature Screenplay award and the DGA's Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Documentary award for creating the film. Folman also received nominations for Annie Awards and BAFTA Awards for Best Animated Feature, but lost both awards to Kung Fu Panda and WALL-E respectively.

|

|

See also[]

- Bachir Gemayel

- Posttraumatic stress disorder

Films[]

References[]

- ^ "WALTZ WITH BASHIR (18)". British Board of Film Classification. 26 August 2008. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ Ari Folman's journey into a heart of darkness Archived 31 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine, International Herald Tribune

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Waltz with Bashir (2008)". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. 15 May 2009. Archived from the original on 21 August 2014. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b The "Waltz with Bashir" Two-Step Archived 16 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Hillel Halkin. Commentary Magazine. March 2009.

- ^ "Golden Globes". Archived from the original on 13 November 2019. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- ^ "Bashir Makes Oscar Cut|Animation Magazine". Archived from the original on 13 November 2019. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- ^ "Dancing With Memory, Massacre In 'Bashir'". NPR. Archived from the original on 17 August 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- ^ Waltz with Bashir Archived 22 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine, DG Design Archived 25 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [https://web.archive.org/web/20120731045513/http://israel21c.org/culture/israeli-filmmakers-head-to-cannes-with-animated-documentary-video/ Archived 31 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine Israeli filmmakers head to Cannes with animated documentary [VIDEO]], Israel21c.org

- ^ "The Responsible Dream: On Waltz with Bashir by Jayson Harsin". Bright Lights Film Journal. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- ^ "A Waltz and an Interview: Speaking with Waltz with Bashir Creator Ari Folman". cincity2000.com. Archived from the original on 15 January 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ "Interview - Ari Folman". Eye Weekly. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 5 February 2009.

- ^ "Total recall- The Irish Times". Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- ^ Ari Folman (author), David Polonsky (Illustrator), Waltz with Bashir: A Lebanon War Story (Atlantic Books, 1 March 2009). ISBN 978-1-84887-068-0

- ^ "Waltz with Bashir". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ Brooks, Xan (15 May 2008). "Bring on the light relief". Cannes diary. London: The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 May 2008. Retrieved 15 May 2008.

- ^ Schilling, Mark (1 December 2008). "'Bashir' wins big at Tokyo Filmex". Variety. Archived from the original on 15 June 2009. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- ^ Walsh, David (24 December 2008). "Waltz With Bashir: 'Memory takes us where we need to go'". World Socialist Web Site. Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ "Shooting Film and Crying". MERIP. 16 March 2009. Archived from the original on 28 June 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ "Israeli film on Lebanon War 'Waltz with Bashir' shown in Beirut". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 11 April 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2009.

- ^ "'Waltz with Bashir' breaks barriers in Arab world". The Jerusalem Post. 22 February 2009. Archived from the original on 17 September 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "Metacritic: 2008 Film Critic Top Ten Lists". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 2 January 2009. Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- ^ "#285: Top 10 Films of 2009—Filmspotting". Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ "Christy Lemire's best movies of 2008 - Orange County Register". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema | 34. Waltz with Bashir". Empire. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ "Best Motion Picture - Foreign Language|Page 3|Golden Globes". Archived from the original on 13 November 2019. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- ^ "'Waltz with Bashir' Makes Golden Globe History". documentary.org. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ "Bashir at Center of Oscar Controversy". Animation Magazine. Archived from the original on 6 January 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2009.

External links[]

- Official website

- Waltz with Bashir at IMDb

- Waltz with Bashir at Box Office Mojo

- Waltz with Bashir at Rotten Tomatoes

- Waltz with Bashir at Metacritic

- "Ari Folman presents his film 'Waltz with Bashir,'" on YouTube, "france24english", 16 May 2008.

- Sebastian Musch: Freud in Beirut - Mechanisms of Trauma in Waltz with Bashir

- 2008 films

- Hebrew-language films

- 2008 animated films

- 2008 documentary films

- Animated documentary films

- Animated drama films

- Flash animated films

- Adult animated films

- Anti-war films

- Best Animated Feature Film Asia Pacific Screen Award winners

- Best Foreign Film César Award winners

- Best Foreign Language Film Golden Globe winners

- César Award winners

- Films scored by Max Richter

- Films about amnesia

- Films about the Israel Defense Forces

- Films set in 1982

- Films set in 2006

- Films set in Beirut

- Films set in Tel Aviv

- Animation controversies

- Israeli films

- Israeli animated films

- Israeli documentary films

- Israeli–Lebanese conflict films

- Israeli–Palestinian conflict films

- 2000s French animated films

- Film controversies

- French films

- German animated films

- Lebanese Civil War films

- Sony Pictures Classics animated films

- 2000s political films

- 2000s war films

- Docuwar films

- Rotoscoped films

- National Society of Film Critics Award for Best Film winners