Western Steppe Herders

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

In archaeogenetics, the term Western Steppe Herders (WSH), or Western Steppe Pastoralists, is the name given to a distinct ancestral component first identified in individuals from the Eneolithic steppe around the turn of the 5th millennium BCE, subsequently detected in several genetically similar or directly related ancient populations including the Khvalynsk, Sredny Stog, and Yamnaya cultures, and found in substantial levels in contemporary European and South Asian populations.[a][b] This ancestry is often referred to as Yamnaya Ancestry, Yamnaya-Related Ancestry, Steppe Ancestry or Steppe-Related Ancestry.[5]

Western Steppe Herders are considered descended from Eastern Hunter-Gatherers (EHGs) who reproduced with Caucasus Hunter-Gatherers (CHGs), and the WSH component is analysed as an admixture of EHG and CHG ancestral components in roughly equal proportions, with the majority of the Y-DNA haplogroup contribution from EHG males. The Y-DNA haplogroups of Western Steppe Herder males are not uniform, with the Yamnaya culture individuals mainly belonging to R1b-Z2103 with a minority of I2a2, the earlier Khvalynsk culture also with mainly R1b but also some R1a, Q1a, J, and I2a2, and the later, high WSH ancestry Corded Ware culture individuals mainly belonging to haplogroup R1a-M417, with some R1b in small numbers.[6][7]

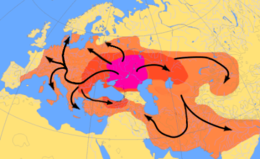

Around 3,000 BC, people of the Yamnaya culture or a closely related group,[1] who had high levels of WSH ancestry with some 10-18% Early European Farmer (EEF) admixture,[4] embarked on a massive expansion throughout Eurasia, which is considered to be associated with the dispersal of at least some of the Indo-European languages by most contemporary linguists, archaeologists, and geneticists. WSH ancestry from this period is often referred to as Steppe Early and Middle Bronze Age (Steppe EMBA) ancestry.[c]

This migration is linked to the origin of both the Corded Ware culture, whose members were of about 75% WSH ancestry, and the Bell Beaker ("Eastern group"), who were around 50% WSH ancestry, though the exact relationships between these groups remains uncertain.[8] The expansion of WSHs resulted in the virtual disappearance of the Y-DNA of Early European Farmers (EEFs) from the European gene pool, significantly altering the cultural and genetic landscape of Europe. During the Bronze Age, Corded Ware people with admixture from Central Europe remigrated onto the steppe, forming the Sintashta culture and a type of WSH ancestry often referred to as Steppe Middle and Late Bronze Age (Steppe MLBA) or Sintashta-Related ancestry.[c] Through the Andronovo culture and Srubnaya culture, Steppe MLBA was carried into Central Asia and South Asia along with Indo-Iranian languages, leaving a long-lasting cultural and genetic legacy.

The modern population of Europe can largely be modeled as a mixture of WHG (Western Hunter-Gatherer), EEF and WSH. In Europe, WSH ancestry peaks among Norwegians (ca. 50%), while in South Asia, it peaks among the Kalash people (ca. 50%), according to Lazaridis et al. (2016). Narasimhan et al. (2019), which employed a wider range of references in their ancestry models, found lower levels of steppe-derived ancestry among modern South Asians (e.g. ~30% among the Kalash).

Summary[]

- 3000 BC: Initial eastward migration initiating the Afanasievo culture, possibly Proto-Tocharian.

- 2900 BC: North-westward migrations carrying Corded Ware culture, transforming into Bell Beaker; according to Anthony, westward migration west of Carpatians into Hungary as Yamnaya, transforming into Bell Beaker, possibly ancestral to Italo-Celtic (disputed).

- 2700 BC: Second eastward migration starting east of Carpatian mountains as Corded Ware, transforming into Fatyanovo-Balanova; (2800 BCE) -> Abashevo; (2200 BCE) -> Sintashta; (2100-1900 BCE) -> Andronovo; (1900-1700 BCE) -> Indo-Aryans.

A summary of several genetic studies published in Nature and Cell during the year 2015 is given by Heyd (2017):

- Western Steppe Herders component "is lower in southern Europe and higher in northern Europe", where inhabitants have roughly 50% WSH ancestry on average. (Haak et al. 2015; Lazaridis et al. 2016)

- It is linked to the migrations of Yamnaya populations dated to ca. 3000 BCE (Allentoft et al. 2015; Haak et al. 2015);

- Third-millennium Europe (and prehistoric Europe in general) was "a highly dynamic period involving large-scale population migrations and replacement" (Allentoft et al. 2015);

- The Yamnaya migrations are linked to the spread of Indo-European languages (Allentoft et al. 2015; Haak et al. 2015);

- The plague (Yersinia pestis) killed prehistoric humans in Europe during the third millennium BCE (Rasmussen et al. 2015), and it stemmed from the Eurasian steppes;

- Yamnaya peoples have the highest ever calculated genetic selection for stature (Mathieson et al. 2015);

Studies[]

Haak et al (2015), Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe[]

Haak et al. (2015) found the ancestry of the people of the Yamnaya culture to be a mix of Eastern Hunter-Gatherer and another unidentified population. All seven Yamnaya males surveyed were found to belong to subclade R-M269 of haplogroup R1b. R1b had earlier been detected among EHGs living further north.[1]

The study found that the tested individuals of the Corded Ware culture were of approximately 75% WSH ancestry, being descended from Yamnaya or a genetically similar population who had mixed with Middle Neolithic Europeans. This suggested that the Yamnaya people or a closely related group embarked on a massive expansion ca. 3,000 BC, which probably played a role in the dispersal of at least some of the Indo-European languages in Europe. At this time, Y-DNA haplogroups common among Early European Farmers (EEFs), such as G2a, disappear almost entirely in Central Europe, and are replaced by WSH/EHG paternal haplogroups which were previously rare (R1b) or unknown (R1a) in this region. EEF mtDNA decreases significantly as well, and is replaced by WSH types, suggesting that the Yamnaya expansion was carried out by both males and females. In the aftermath of the Yamnaya expansion there appears to have been a resurgence of EEF and Western Hunter-Gatherer (WHG) ancestry in Central Europe, as this is detected in samples from the Bell Beaker culture and its successor the Unetice culture.[1] The Bell Beaker culture had about 50% WSH ancestry.[12]

All modern European populations can be modeled as a mixture of WHG, EEF and WSH. WSH ancestry is more common in Northern Europe than Southern Europe. Of modern populations surveyed in the study, Norwegians were found to have the largest amount of WSH ancestry, which among them exceeded 50%.[1]

Allentoft et al. (2015), Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia[]

Allentoft et al. (2015) examined the Y-DNA of five Yamnaya males. Four belonged to types of R1b1a2, while one belonged to I2a2a1b1b. The study found that the Neolithic farmers of Central Europe had been "largely replaced" by Yamnaya people around 3,000 BC. This replacement altered not only the genetic landscape, but also the cultural landscape of Europe in many respects.[13]

It was discovered that the people of the contemporary Afanasievo culture of southern Siberia were "genetically indistinguishable" from the Yamnaya. People of the Corded Ware culture, the Bell Beaker culture, the Unetice culture and the Nordic Bronze Age were found to be genetically very similar to one another, but also with varying levels of affinity to Yamnaya, the highest found in Corded Ware individuals. The authors of the study suggested that the Sintashta culture of Central Asia emerged as a result of an eastward migration from Central Europe of Corded Ware people with both WSH and European Neolithic farmer ancestry.[13]

Jones et al. (2015), Upper Palaeolithic genomes reveal deep roots of modern Eurasians[]

Jones et al. (2015) found that the WSHs were descended from admixture between EHGs and a previously unknown clade which the authors identify and name Caucasus hunter-gatherers (CHGs). CHGs were found to have split off from WHGs ca. 43,000 BC, and to have split off from EEFs ca. 23,000 BC. It was estimated that Yamnaya "owe half of their ancestry to CHG-linked sources."[14]

Mathieson et al. (2015), Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians[]

Mathieson et al. (2015), Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians, published in Nature in November 2015 found that the people of the Poltavka culture, Potapovka culture and Srubnaya culture were closely related and largely of WSH descent, although the Srubnaya carried more EEF ancestry (about 17%) than the rest. Like in Yamnaya, males of Poltavka mostly carried types of R1b, while Srubnaya males carried types of R1a.[15]

The study found that most modern Europeans could be modelled as a mixture between WHG, EEF and WSH.[d]

Genomic insights into the origin of farming in the ancient Near East[]

A genetic study published in Nature in July 2016 found that WSHs were a mixture of EHGs and "a population related to people of the Iran Chalcolithic". EHGs were modeled as being of 75% Ancient North Eurasian (ANE) descent. A significant presence of WSH ancestry among populations of South Asia was detected. Here WSH ancestry peaked at 50% among the Kalash people, which is a level similar to modern populations of Northern Europe.[16]

Genetic Origins of the Minoans and Mycenaeans[]

Lazaridis et al. (2017) examined the genetic origins of the Mycenaeans and the Minoans. Although they were found to be genetically similar to Minoans, the Mycenaeans were found to harbor about 15% WSH ancestry, which was not present in Minoans. It was found that Mycenaeans could be modelled as a mixture of WSH and Minoan ancestry. The study asserts that there are two key questions remaining to be addressed by future studies. First, when did the common "eastern" ancestry of both Minoans and Mycenaeans arrive in the Aegean? Second, is the "northern" ancestry in Mycenaeans due to sporadic infiltration of Greece, or the result of a rapid migration as in Central Europe? Such a migration would support the idea that proto-Greek speakers formed the southern wing of a steppe intrusion of Indo-European speakers. Yet, the absence of "northern" ancestry in the Bronze Age samples from Pisidia, where Indo-European languages were attested in antiquity, casts doubt on this genetic-linguistic association, with further sampling of ancient Anatolian speakers needed.[17]

The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of northwest Europe[]

Olalde et al. (2018) examined the entry of WSH ancestry into the British Isles. WSH ancestry was found to have been carried into the British Isles by the Bell Beaker culture in the second half of the 3rd millennium BC. The migrations of Bell Beakers were accompanied with "a replacement of ~90% of Britain's gene pool within a few hundred years". The gene pool in the British Isles had previously been dominated by EEFs with slight WHG admixture.[e]

Y-DNA in parts of the modern British Isles belongs almost entirely to R1b-M269, a WSH lineage, which is thought to have been brought to the isles with Bell Beakers.[18]

The Genomic History of Southeastern Europe[]

A genetic study published in Nature in February 2018 noted that the modern population of Europe can largely be modeled as a mixture between EHG, WHG, WSH and EEF.[f]

The study examined individuals from the Globular Amphora culture, who bordered the Yamnaya. Globular Amphora culture people were found to have no WSH ancestry, suggesting that cultural differences and genetic differences were connected.[12]

Notably, WSH ancestry was detected among two individuals buried in modern-day Bulgaria ca. 4,500 BC. This showed that WSH ancestry appeared outside of the steppe 2,000 years earlier than previously believed.[12]

The First Horse Herders and the Impact of Early Bronze Age Steppe Expansions into Asia[]

Damgaard et al. 2018 found that that Yamnaya-related migrations had a lower direct and long-lasting impact in East and South Asia than in Europe. Crucially, the Botai culture of Late Neolithic Central Asia was found to have no WSH ancestry, suggesting that they belonged to an ANE-derived population deeply diverged from the WSHs.[19]

Bronze Age population dynamics and the rise of dairy pastoralism on the eastern Eurasian steppe[]

A genetic study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America in November 2018 examined the presence of WSH ancestry in the Mongolian Plateau. A number of remains from Late Bronze Age individuals buried around Lake Baikal were studied. These individuals had only 7% WSH ancestry, suggesting that pastoralism was adopted on the Eastern Steppe through cultural transmission rather than genetic displacement.[2]

The study found that WSH ancestry found among Late Bronze Age populations of the south Siberia such as the Karasuk culture was transmitted through the Andronovo culture rather than the earlier Afanasievo culture, whose genetic legacy in the region by this time was virtually non-existent.[2]

Ancient Human Genome-Wide Data From a 3000-Year Interval in the Caucasus Corresponds with Eco-Geographic Regions[]

A genetic study published in Nature Communications in February 2019 compared the genetic origins of the Yamnaya culture and the Maikop culture. It found that most of the EEF ancestry found among the Yamnaya culture was derived from the Globular Amphora culture and the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture of Eastern Europe.[4][20] Total EEF ancestry among the Yamnaya has been estimated at 10-18%. Given the high amount of EEF ancestry in the Maikop culture, this makes it impossible for the Maikop culture to have been a major source of CHG ancestry among the WSHs. Admixture from the CHGs into the WSHs must thus have happened at an earlier date.[20]

The genomic history of the Iberian Peninsula over the past 8000 years[]

Olalde et al. (2019) analyzed the process by which WSH ancestry entered the Iberian Peninsula. The earliest evidence of WSH ancestry there was found from an individual living in Iberia in 2,200 BC in close proximity with native populations. By 2,000 BC, the native Y-DNA of Iberia (H, G2 and I2) had been almost entirely replaced with a single WSH lineage, R-M269. mtDNA in Iberia at this time was however still mostly of native origin, affirming that the entry of WSH ancestry in Iberia was primarily male-driven.[g]

Narasimhan et al. (2019), The Genomic Formation of South and Central Asia[]

Narasimhan et al. (2019), The Genomic Formation of South and Central Asia, published in Science in September 2019, found a large amount of WSH ancestry among Indo-European-speaking populations throughout Eurasia. This lent support to the theory that the Yamnaya people were Indo-European-speaking.[3]

The study found people of the Corded Ware, Srubnaya, Sintashta and Andronovo cultures to be a closely related group almost wholly of WSH ancestry, but with slight European Middle Neolithic admixture. These results further underpinned the notion that the Sintashta culture emerged as an eastward migration of Corded Ware peoples with mostly WSH ancestry back into the steppe. Among early WSHs, R1b is the most common Y-DNA lineage, while R1a (particularly R1a1a1b2) is common among later groups of Central Asia, such as Andronovo and Srubnaya.[3]

West Siberian Hunter-Gatherers (WSGs), a distinct archaeogenetic lineage, was discovered in the study. These were found to be of about 30% EHG ancestry, 50% ANE ancestry, and 20% East Asian ancestry. It was noticed that WSHs during their expansion towards the east gained a slight (ca. 8%) admixture from WSGs.[3]

It was found that there was a significant infusion of WSH ancestry into Central Asia and South Asia during the Bronze Age. WSH ancestry was found to have been almost completely absent from earlier samples in southern Central Asia in the 3rd millennium BC.[h]

During the expansion of WSHs from Central Asia towards South Asia in the Bronze Age, an increase in South Asian agriculturalist ancestry among WSHs was noticed. Among South Asian populations, WSH ancestry is particularly high among Brahmins and Bhumihars. WSH ancestry was thus expected to have spread into India with the Vedic culture.[3]

Antonio et al.(2019), Ancient Rome: A genetic crossroads of Europe and the Mediterranean[]

Antonio et al. (2019), Ancient Rome: A genetic crossroads of Europe and the Mediterranean, published in Science in November 2019 examined the remains of six Latin males buried near Rome between 900 BC and 200 BC. They carried the paternal haplogroups R-M269, T-L208, R-311, R-PF7589 and R-P312 (two samples), and the maternal haplogroups H1aj1a, T2c1f, H2a, U4a1a, H11a and H10. A female from the preceding Proto-Villanovan culture carried the maternal haplogroups U5a2b.[22] These examined individuals were distinguished from preceding populations of Italy by the presence of ca. 30-40% steppe ancestry.[23] Genetic differences between the examined Latins and the Etruscans were found to be insignificant.[24]

Fernandes et al. (2019), The Arrival of Steppe and Iranian Related Ancestry in the Islands of the Western Mediterranean[]

Fernandes et al. (2019), The Arrival of Steppe and Iranian Related Ancestry in the Islands of the Western Mediterranean, found that a skeleton excavated from the Balearic islands (dating to ∼2400 BCE) had substantial WSH ancestry; however, later Balearic individuals had less Steppe heritage reflecting geographic heterogeneity or immigration from groups with more European first farmer-related ancestry. In Sicily, WSH ancestry arrived by ∼2200 BCE and likely came at least in part from Spain. 4 of the 5 Early Bronze Age Sicilian males had Steppe-associated Y-haplogroup R1b1a1a2a1a2 (R-P312). Two of these were Y-haplogroup R1b1a1a2a1a2a1 (Z195) which today is largely restricted to Iberia and has been hypothesized to have originated there 2500-2000 BCE. In Sardinia, no convincing evidence of WSH ancestry in the Bronze Age has been found, but the authors detect it by ∼200-700 CE.[25]

Analysis[]

The American archaeologist David W. Anthony (2019) analyzed the recent genetic data on WSHs. Anthony notes that WSHs display genetic continuity between the paternal lineages of the Dnieper-Donets culture and the Yamnaya culture, as the males of both cultures have been found to have been mostly carriers of R1b, and to a lesser extent I2.[12]

While the mtDNA of the Dnieper-Donets people is exclusively types of U, which is associated with EHGs and WHGs, the mtDNA of the Yamnaya also includes types frequent among CHGs and EEFs. Anthony notes that WSH had earlier been found among the Sredny Stog culture and the Khvalynsk culture, who preceded the Yamnaya culture on the Pontic–Caspian steppe. The Sredny Stog were mostly WSH with slight EEF admixture, while the Khvalynsk living further east were purely WSH. Anthony also notes that unlike their Khvalynsk predecessors, the Y-DNA of the Yamnaya is exclusively EHG and WHG. This implies that the leading clans of the Yamnaya were of EHG and WHG origin.[27] Because the slight EEF ancestry of the WSHs has been found to be derived from Central Europe, and because there is no CHG Y-DNA detected among the Yamnaya, Anthony notes that it is impossible for the Maikop culture to have contributed much to the culture or CHG ancestry of the WSHs. Anthony suggests that admixture between EHGs and CHGs first occurred on the eastern Pontic-Caspian steppe around 5,000 BC, while admixture with EEFs happened in the southern parts of the Pontic-Caspian steppe sometime later.[6]

As Yamnaya Y-DNA is exclusively of the EHG and WHG type, Anthony notes that the admixture must have occurred between EHG and WHG males, and CHG and EEF females. Anthony cites this as additional evidence that the Indo-European languages were initially spoken among EHGs living in Eastern Europe. On this basis, Anthony concludes that the Indo-European languages which the WSHs brought with them were initially the result of "a dominant language spoken by EHGs that absorbed Caucasus-like elements in phonology, morphology, and lexicon" (spoken by CHGs).[6]

Phenotypes[]

Western Steppe Herders are believed to have been light-skinned. Early Bronze Age Steppe populations such as the Yamnaya are believed to have had mostly brown eyes and dark hair,[13][28] while the people of the Corded Ware culture had a higher proportion of blue eyes.[29][30]

The rs12821256 allele of the KITLG gene that controls melanocyte development and melanin synthesis,[31] which is associated with blond hair and first found in an individual from central Asia dated to around 15,000 BC, is found in three Eastern Hunter-Gatherers from Samara, Motala and Ukraine, and several later individuals with WSH ancestry.[12] Geneticist David Reich concludes that the massive migration of Western Steppe Herders probably brought this mutation to Europe, explaining why there are hundreds of millions of copies of this SNP in modern Europeans.[32] In 2020, a study suggested that ancestry from Western Steppe Pastoralists was responsible for lightening the skin and hair color of modern Europeans, having a dominant effect on the phenotype of Northern Europeans, in particular.[33]

A study in 2015 found that Yamnaya had the highest ever calculated genetic selection for height of any of the ancient populations tested.[15][29]

About a quarter of ancient DNA samples from Yamnaya sites have an allele that is associated with lactase persistence, conferring lactose tolerance into adulthood.[34] Steppe-derived populations such as the Yamnaya are thought to have brought this trait to Europe from the Eurasian steppe, and it is hypothesized that it may have given them a biological advantage over the European populations who lacked it.[35][36][37]

Eurasian steppe populations display higher frequencies of the lactose tolerance allele than European farmers and hunter gatherers who lacked steppe admixture.[38]

See also[]

Notes[]

- ^ "North of the Caucasus, Eneolithic and BA individuals from the Samara region (5200–4000 BCE) carry an equal mixture of EHG and CHG/Iranian ancestry, so-called ‘steppe ancestry’ that eventually spread further west, where it contributed substantially to present-day Europeans, and east to the Altai region as well as to South Asia."[4]

- ^ "Recent paleogenomic studies have shown that migrations of Western steppe herders (WSH) beginning in the Eneolithic (ca. 3300–2700 BCE) profoundly transformed the genes and cultures of Europe and central Asia... The migration of these Western steppe herders (WSH), with the Yamnaya horizon (ca. 3300–2700 BCE) as their earliest representative, contributed not only to the European Corded Ware culture (ca. 2500–2200 BCE) but also to steppe cultures located between the Caspian Sea and the Altai-Sayan mountain region, such as the Afanasievo (ca. 3300–2500 BCE) and later Sintashta (2100–1800 BCE) and Andronovo (1800–1300 BCE) cultures."[2]

- ^ a b "We collectively refer to as "Western Steppe Herders (WSH)": the earlier populations associated with the Yamnaya and Afanasievo cultures (often called "steppe Early and Middle Bronze Age"; "steppe_EMBA") and the later ones associated with many cultures such as Potapovka, Sintashta, Srubnaya and Andronovo to name a few (often called "steppe Middle and Late Bronze Age"; "steppe_MLBA")."[5]

- ^ "Most present-day Europeans can be modeled as a mixture of three ancient populations related to Mesolithic hunter-gatherers (WHG), early farmers (EEF) and steppe pastoralists (Yamnaya)."[15]

- ^ "[M]igration played a key role in the further dissemination of the Beaker Complex, a phenomenon we document most clearly in Britain, where the spread of the Beaker Complex introduced high levels of Steppe-related ancestry and was associated with a replacement of ~90% of Britain's gene pool within a few hundred years."[18]

- ^ "It has previously been shown that the great majority of European ancestry derives from three distinct sources. First, "hunter-gatherer-related" ancestry that is more closely related to Mesolithic hunter-gatherers from Europe than to any other population, and can be further subdivided into "Eastern" (EHG) and "Western" (WHG) hunter-gatherer-related ancestry.7 Second, "NW Anatolian Neolithic-related" ancestry related to the Neolithic farmers of northwest Anatolia and tightly linked to the appearance of agriculture. The third source, "steppe-related" ancestry, appears in Western Europe during the Late Neolithic to Bronze Age transition and is ultimately derived from a population related to Yamnaya steppe pastoralists. Steppe-related ancestry itself can be modeled as a mixture of EHG-related ancestry, and ancestry related to Upper Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers of the Caucasus (CHG) and the first farmers of northern Iran."[12]

- ^ "We reveal sporadic contacts between Iberia and North Africa by ~2500 BCE, and by ~2000 BCE the replacement of 40% of Iberia's ancestry and nearly 100% of its Y-chromosomes by people with Steppe ancestry... Y-chromosome turnover was even more dramatic, as the lineages common in Copper Age Iberia (I2, G2, H) were nearly completely replaced by one lineage, R1b-M269."[21]

- ^ "Importantly, in the 3rd millennium BCE we do not find any individuals with ancestry derived from Yamnaya-related Steppe pastoralists in Turan. Thus, Steppe_EMBA ancestry was not yet widespread across the region."[3]

References[]

- ^ a b c d e Haak et al. 2015.

- ^ a b c d Jeong et al. 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Narasimhan et al. 2019.

- ^ a b c Wang et al. 2019.

- ^ a b Jeong et al. 2019.

- ^ a b c Anthony 2019a, pp. 1–19.

- ^ Malmström et al. 2019.

- ^ Bianca Preda (May 6, 2020). "Yamnaya - Corded Ware - Bell Beakers: How to conceptualise events of 5000 years ago". The Yamnaya Impact On Prehistoric Europe. University of Helsinki. Retrieved August 5, 2021. (Heyd 2019)

- ^ Anthony, David W. (2007). The Horse, The Wheel and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World.

- ^ Anthony, David (2017). "Archaeology and Language: Why Archaeologists Care About the Indo-European Problem". In Crabtree, P.J.; Bogucki, P. (eds.). European Archaeology as Anthropology: Essays in Memory of Bernard Wailes.

- ^ Nordgvist, Kerkko; Heyd, Volker (November 12, 2020). "The Forgotten Child of the Wider Corded Ware Family: Russian Fatyanovo Culture in Context". Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. 86: 65–93. doi:10.1017/ppr.2020.9. S2CID 228923806.

- ^ a b c d e f Mathieson et al. 2018.

- ^ a b c Allentoft et al. 2015.

- ^ Jones et al. 2015.

- ^ a b c Mathieson et al. 2015.

- ^ Lazaridis et al. 2016.

- ^ Lazaridis et al. 2017.

- ^ a b Olalde 2018.

- ^ Damgaard et al. 2018.

- ^ a b Anthony 2019b, p. 32.

- ^ Olalde 2019.

- ^ Antonio et al. 2019, Table 2 Sample Information, Rows 29-32, 36-37.

- ^ Antonio et al. 2019, p. 2.

- ^ Antonio et al. 2019, p. 3.

- ^ Fernandes et al. 2019.

- ^ Mallory 1991, pp. 175–176.

- ^ Anthony 2019b, p. 36.

- ^ Gibbons 2015.

- ^ a b Heyd 2017.

- ^ Frieman, Catherine J.; Hofmann, Daniela (August 8, 2019). "Present pasts in the archeology of genetics, identity and migration in Europe: a critical essay". World Archaeology. 51 (4): 528–545. doi:10.1080/00438243.2019.1627907. hdl:1956/22151. ISSN 0043-8243. S2CID 204480648.

- ^ Sulem, Patrick; Gudbjartsson, Daniel F.; Stacey, Simon N.; Helgason, Agnar; Rafnar, Thorunn; Magnusson, Kristinn P.; Manolescu, Andrei; Karason, Ari; Palsson, Arnar; Thorleifsson, Gudmar; et al. (December 2007). "Genetic determinants of hair, eye and skin pigmentation in Europeans". Nature Genetics. 39 (12): 1443–1452. doi:10.1038/ng.2007.13. ISSN 1546-1718. PMID 17952075. S2CID 19313549.

- ^ Reich 2018, p. 96. "The earliest known example of the classic European blond hair mutation is in an Ancient North Eurasian from the Lake Baikal region of eastern Siberia from seventeen thousand years ago. The hundreds of millions of copies of this mutation in central and western Europe today likely derive from a massive migration of people bearing Ancient North Eurasian ancestry, an event that is related in the next chapter."

- ^ Hanel, Andrea; Carlberg, Carsten (2020). "Skin colour and vitamin D: An update". Experimental Dermatology. 29 (9): 864–875. doi:10.1111/exd.14142. PMID 32621306.

- ^ Saag, L (2020). "Human Genetics: Lactase Persistence in a Battlefield". Current Biology. 30 (21): R1311–R1313. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.08.087. PMID 33142099. S2CID 226229587.

- ^ Segurel, Laure; Guarino-Vignon, Perle; Marchi, Nina; Lafosse, Sophie; Laurent, Romain; Bon, Céline; Fabre, Alexandre; Hegay, Tatyana; Heyer, Evelyne (2020). "Why and when was lactase persistance selected for? Insights from Central Asian herders and ancient DNA". PLOS Biology. 18 (6): e3000742. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000742. PMC 7302802. PMID 32511234. "Furthermore, ancient DNA studies found that the LP mutation was absent or very rare in Europe until the end of the Bronze Age [26–29] and appeared first in individuals with steppe ancestry [19,20]. Thus, it was proposed that the mutation originated in Yamnaya-associated populations and arrived later in Europe by migration of these steppe herders."

- ^ Callaway, Ewen (June 10, 2015). "DNA data explosion lights up the Bronze Age". Nature. 522 (7555): 140–141. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..140C. doi:10.1038/522140a. PMID 26062491. "the 101 sequenced individuals, the Yamnaya were most likely to have the DNA variation responsible for lactose tolerance, hinting that the steppe migrants might have eventually introduced the trait to Europe"

- ^ Furholt, Martin (2018). "Massive Migrations? The Impact of Recent DNA Studies on our View of Third Millennium Europe". European Journal of Archaeology. 21 (2): 159–191. doi:10.1017/eaa.2017.43. "For example, one lineage could have a biological evolutionary advantage over the other. (Allentoft et al. 2015, p. 171) have found a remarkably high rate of lactose tolerance among individuals connected to Yamnaya and to Corded Ware, as opposed to the majority of Late Neolithic individuals."

- ^ Gross, Michael (2018). "On the origin of cheese". Current Biology. 28 (20): R1171–R1173. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.10.008. "The highest prevalence of tolerance detected in that study was found among the Yamnaya of the Eurasian steppe, and the highest within Europe was among the Corded Ware cultures "

Bibliography[]

- Allentoft, Morten E.; Sikora, Martin; Sjögren, Karl-Göran; Rasmussen, Simon; Rasmussen, Morten; Stenderup, Jesper; Damgaard, Peter B.; Schroeder, Hannes; Ahlström, Torbjörn; Vinner, Lasse; et al. (2015). "Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia". Nature. 522 (7555): 167–172. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..167A. doi:10.1038/nature14507. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 26062507. S2CID 4399103.

- Anthony, David (Spring–Summer 2019a). "Archaeology, Genetics, and Language in the Steppes: A Comment on Bomhard". Journal of Indo-European Studies. 47 (1–2): 1–23. Retrieved January 9, 2020.

- Anthony, David W. (2019b). "Ancient DNA, Mating Networks, and the Anatolian Split". In Serangeli, Matilde; Olander, Thomas (eds.). Dispersals and Diversification: Linguistic and Archaeological Perspectives on the Early Stages of Indo-European. BRILL. pp. 21–54. ISBN 978-9004416192.

- Antonio, Margaret L.; et al. (November 8, 2019). "Ancient Rome: A genetic crossroads of Europe and the Mediterranean". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 366 (6466): 708–714. Bibcode:2019Sci...366..708A. doi:10.1126/science.aay6826. PMC 7093155. PMID 31699931.

- Damgaard, Peter de Barros; et al. (June 29, 2018). "The first horse herders and the impact of early Bronze Age steppe expansions into Asia". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 360 (6396): eaar7711. doi:10.1126/science.aar7711. PMC 6748862. PMID 29743352.

- Fernandes, Daniel M.; et al. (March 21, 2019). "The Arrival of Steppe and Iranian Related Ancestry in the Islands of the Western Mediterranean". bioRxiv 10.1101/584714.

- Gibbons, A. (July 24, 2015). "Revolution in human evolution". Science. 349 (6246): 362–366. Bibcode:2015Sci...349..362G. doi:10.1126/science.349.6246.362. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 26206910.

- Haak, Wolfgang; Lazaridis, Iosif; Patterson, Nick; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Llamas, Bastien; Brandt, Guido; Nordenfelt, Susanne; Harney, Eadaoin; Stewardson, Kristin; et al. (2015). "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". Nature. 522 (7555): 207–211. arXiv:1502.02783. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. doi:10.1038/nature14317. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 5048219. PMID 25731166.

- Heyd, Volker (April 2017). "Kossinna's smile" (PDF). Antiquity. 91 (356): 348–359. doi:10.15184/aqy.2017.21. hdl:10138/255652. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 164376362.

- Heyd, Volker (2019). "Yamnaya – Corded Wares – Bell Beakers, or How to Conceptualize Events of 5000 Years Ago that Shaped Modern Europe". STUDIA IN HONOREM ILIAE ILIEV [Studies in honor of Ilia Iliev] (PDF). News of the Yambol Museum / year VI, issue 9. pp. 125–136. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- Jeong, Choongwon; et al. (November 27, 2018). "Bronze Age population dynamics and the rise of dairy pastoralism on the eastern Eurasian steppe". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. National Academy of Sciences. 115 (48): 966–976. doi:10.1073/pnas.1813608115. PMC 6275519. PMID 30397125.

- Jeong, Choongwon; et al. (April 29, 2019). "The genetic history of admixture across inner Eurasia languages in Europe". Nature Ecology and Evolution. Nature Research. 3 (6): 966–976. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0878-2. PMC 6542712. PMID 31036896.

- Jones, Eppie R.; et al. (November 16, 2015). "Upper Palaeolithic genomes reveal deep roots of modern Eurasians". Nature Communications. Nature Research. 6 (8912): 8912. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.8912J. doi:10.1038/ncomms9912. PMC 4660371. PMID 26567969.

- Lazaridis, Iosif; et al. (July 25, 2016). "Genomic insights into the origin of farming in the ancient Near East". Nature. Nature Research. 536 (7617): 419–424. Bibcode:2016Natur.536..419L. doi:10.1038/nature19310. PMC 5003663. PMID 27459054.

- Lazaridis, Iosif; et al. (August 2, 2017). "Genetic origins of the Minoans and Mycenaeans". Nature. Nature Research. 548 (7666): 214–218. Bibcode:2017Natur.548..214L. doi:10.1038/nature23310. PMC 5565772. PMID 28783727.

- Mallory, J.P. (1991). In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language Archeology and Myth. Thames & Hudson.

- Malmström, Helena; Günther, Torsten; Svensson, Emma M.; Juras, Anna; Fraser, Magdalena; Munters, Arielle R.; Pospieszny, Łukasz; Tõrv, Mari; Lindström, Jonathan; Götherström, Anders; Storå, Jan; Jakobsson, Mattias (October 9, 2019). "The genomic ancestry of the Scandinavian Battle Axe Culture people and their relation to the broader Corded Ware horizon". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 286 (1912). 20191528. doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.1528. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 6790770. PMID 31594508.</ref>

- Mathieson, Iain; Lazaridis, Iosif; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Patterson, Nick; Roodenberg, Songül Alpaslan; Harney, Eadaoin; Stewardson, Kristin; Fernandes, Daniel; Novak, Mario; et al. (2015). "Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians". Nature. 528 (7583): 499–503. Bibcode:2015Natur.528..499M. doi:10.1038/nature16152. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 4918750. PMID 26595274.

- Mathieson, Iain; et al. (February 21, 2018). "The Genomic History of Southeastern Europe". Nature. Nature Research. 555 (7695): 197–203. Bibcode:2018Natur.555..197M. doi:10.1038/nature25778. PMC 6091220. PMID 29466330.

- Narasimhan, Vagheesh M.; Patterson, Nick; Moorjani, Priya; Rohland, Nadin; Bernardos, Rebecca (September 6, 2019). "The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 365 (6457): eaat7487. bioRxiv 10.1101/292581. doi:10.1126/science.aat7487. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 6822619. PMID 31488661.

- Olalde, Iñigo (February 21, 2018). "The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of northwest Europe". Nature. Nature Research. 555 (7695): 190–196. Bibcode:2018Natur.555..190O. doi:10.1038/nature25738. PMC 5973796. PMID 29466337.

- Olalde, Iñigo (March 15, 2019). "The genomic history of the Iberian Peninsula over the past 8000 years". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 363 (6432): 1230–1234. Bibcode:2019Sci...363.1230O. doi:10.1126/science.aav4040. PMC 6436108. PMID 30872528.

- Rasmussen, Simon; Allentoft, Morten Erik; Nielsen, Kasper; Orlando, Ludovic; Sikora, Martin; Sjögren, Karl-Göran; Pedersen, Anders Gorm; Schubert, Mikkel; Van Dam, Alex; Kapel, Christian Moliin Outzen; et al. (October 22, 2015). "Early Divergent Strains of Yersinia pestis in Eurasia 5,000 Years Ago". Cell. 163 (3): 571–582. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.009. ISSN 0092-8674. PMC 4644222. PMID 26496604.

- Reich, David (2018). Who We are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198821250.

- Wang, Chuan-Chao; Reinhold, Sabine; Kalmykov, Alexey; Wissgott, Antje; Brandt, Guido; Jeong, Choongwon; Cheronet, Olivia; Ferry, Matthew; Harney, Eadaoin; Keating, Denise; et al. (February 4, 2019). "Ancient human genome-wide data from a 3000-year interval in the Caucasus corresponds with eco-geographic regions". Nature Communications. Nature Research. 10 (1). 590. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10..590W. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-08220-8. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6360191. PMID 30713341.

Further reading[]

- Barras, Colin (March 27, 2019). "Story of most murderous people of all time revealed in ancient DNA". New Scientist. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- Kuzmina, Elena E. (2007). Mallory, J. P. (ed.). The Origin of the Indo-Iranians. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004160545.

- Lazaridis, Iosif (December 2018). "The evolutionary history of human populations in Europe". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. Elsevier. 53: 21–27. arXiv:1805.01579. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2018.06.007. PMID 29960127. S2CID 19158377. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Archaeogenetic lineages

- Genetic history of Europe

- Neolithic Europe

- Bronze Age Europe

- Modern human genetic history